The history of clockmaking in Besançon began significantly at the end of the 18th century, when Swiss clockmakers set up their first workshops in the Comtois capital. Then, little by little, the people of Besançon joined in the clockmaking fever, definitively transforming Besançon into the Capitale française de l'horlogerie (French capital of clockmaking) at the 1860 International Exhibition, held in Place Labourey. The city produced up to 90% of French watches by 1880, and despite a crisis in the 1890s and 1900s, the clockmaking sector recovered and continued to grow. The city continued to play a leading role in the clockmaking industry until the crisis of the 1930s, and recovered before the end of World War II, but the industry lost a significant share of its activity after the end of this conflict. The 1970s brought an end to this mythical epic, as the major companies went into decline in the wake of the oil crisis.

However, the clockmaking industry remained very much alive in the town. For several generations, the life of the inhabitants was shaped by this industry, particularly in terms of skilled employment. And although today the number of workshops is low, representing just 89 establishments and 2,119 salaried jobs in the whole region, Besançon nonetheless retains indelible traces of this rich past. The Dodane watchmaking factory, the Musée du Temps, the monumental clock at the Viotte train station and the École d'Horlogerie de Besançon, now a nationally recognized institution, bear witness to this, as do companies such as Lip, Yema, Zenith and Maty, which are among the most emblematic names in clockmaking in Besançon. Many will also be familiar with the Lip affair, which highlighted the crisis of the 1970s for an entire industry in the town of Besançon. Last but not least, some of the great names in clockmaking still resonate in the city: Laurent Mégevand, founder of the industry in the city.

History

See also: Timeline of BesançonClockmaking in Besançon and its surrounding area before 1793

Clockmaking has existed in the Franche-Comté region since the late 17th century, thanks in particular to the Grandfatherclock. Indeed, this pendulum clock, made in particular in Morez and Morbier in the Haut Jura, is considered one of the region's typical industries, before industrial production came to a halt at the beginning of the 20th century. For more than three centuries, this simple, robust clock was a great success: at its peak, production reached 150,000 pieces a year in the 1850s.

Besançon's clockmaking activities pre-dated the arrival of the Swiss and the French Revolution, but were carried out exclusively by small workshops such as Paliard, Lareche, Joffroy, Perrot and Perron, who were considered master clockmakers of their time. The most illustrious of these is Perron, who is notably the author of such renowned pieces as the Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI clocks, renowned for their high quality. These craftsmen made all the clocks themselves before industrial production was imported to the town by the Swiss.

The founding of industrial clockmaking

In 1793, Genevan Laurent Mégevand (1754-1814) settled in Besançon with 80 colleagues, founding the city's clockmaking industry, apparently to escape unemployment or because of his political activities. They subsequently brought 22 clockmaking families to the city, representing between 400 and 700 people, mainly from Le Locle and the principality of Neuchâtel, but also from Geneva, Porrentruy, Montbéliard, Savoy, and even the Palatinate. These immigrants were greatly encouraged by the French authorities, notably by a decree in 1793 which founded the Manufacture Française d'Horlogerie in Besançon, offering them spacious premises and subsidies. These links with the Swiss workers' milieu were to prove decisive, both socially and politically, for the Besançon Commune project fomented in 1871.

In 1795, there were a thousand clockmaking in the city, and by the end of the Empire, some 1,500 Swiss lived in the Comtoise capital, 500 of them working exclusively in watchmaking and producing around 20,000 units a year, before this community was gradually replaced by local labor. In 1801, the first clockmaking apprenticeship workshop was set up in the Hôpital Saint-Jacques, but the real craze for clockmaking education in Besançon dates from the 1850s. Watch production rose from 14,700 pieces in Year III (1794-1795) to 21,400 in Year XI (1802-1803). After the end of the favors granted to Swiss immigrants, most of them returned to their native region or saw their businesses go bankrupt, as in the case of Mégevand, who died in poverty in 1814. However, even if the initiators of the town's clockmaking movement were in a bad way, the industrial pole was well established: Franc-Comtois watchmaking was born.

A family workshop appeared in the 1800s: Lip, founded by Emmanuel Lipmann. A testimonial reports the existence of this small workshop as early as the 1800s; it was to become one of France's largest clock manufacturers: "In 1800, the future emperor, who was still only First Consul, was visiting Besançon. On this occasion, a clockmaking presented him with a clock in the name of the Israelite Consistory, of which he was president. This is a character from a novel, wearing a velvet skullcap and an abundant beard. Originally, Emmanuel Lipmann was an artisan clockmaker who, when he wasn't bent over his clocks, magnifying glass in hand, roamed the Alsatian plain, repairing clocks or selling his own work, half peddler, half clock doctor. In winter, he returned to his village, his workshop and his workbench, preparing for the next season . But our man remained faithful to his native Franche-Comté. He bears a name which, minus its second syllable, is today the most popular in the clockmaking industry. He is the ancestor of all the Lip companies who, from a small firm of fifteen people set up in 1867 by Emmanuel Lipmann in Besançon's Grande Rue, went on to become the most powerful of all French manufacturers." In 1807, a pocket watch was presented to Napoleon Bonaparte by the Jewish community of Besançon. This event marked a turning point in the city's clockmaking history, but also for Besançon's Jewish community.

From early developments to initial crisis

During the first half of the 19th century, watch production remained modest: in 1804, around 25,000 pieces were produced, and during the Restoration some 50,000, although a large number turned out to be of Swiss origin; actual production was counted from 1821, with a total of 30,000 pieces. After the Revolution of 1830, clockmaking took off in the region, but remained stagnant in the Comtois capital. It wasn't until the Third Republic that the clockmaking industry experienced a sharp upturn: 5,600 pieces in 1847; 100,000 in 1854; 200,000 in 1860; 373,138 in 1869; 395,000 watches in 1872; 493,933 in 1882; then 501,602 in 1883. In 1880, according to the Chamber of Commerce, Besançon accounted for 90% of French watch production, with some 5,000 workers specialized in this sector, and no less than 10,000 women working part-time. At the International Universal Exhibition held on Place Labourey in Besançon in 1860, the city was recognized as the Capitale de la montre française (Capital of French Watches). In 1862, the first clockmaking school opened in the Comtois capital under the direction of M. Courvoisier, a Swiss master watchmaker originally from Fleurier. The town became home to the first French watch factory in 1874, with production reaching 395,000 pieces that year, representing a 12% share of total world watch production.

However, a crisis struck in the late 1880s: thousands of jobs disappeared and many inhabitants left the town for lack of work, while others saw their wages drastically cut; production fell to 366,197 watches in 1888. The causes of this decline are many and difficult to pinpoint: the industrial crisis, overproduction, misunderstanding and lack of initiative on the part of clockmakers in Besançon, the attitude of the government, which encouraged clockmaking schools in Cluses and Paris while neglecting the Besançon school, and above all Swiss competition, considered unfair by the profession. In fact, the French authorities regarded a watch as a piece of jewelry because of its casing, which was usually made of gold or silver, and the French product was therefore subjected to a series of rigorous, heavily taxed tests designed to check the reliability of the finished piece. Every French manufacturer was obliged to take his boxes to the guarantee office, where an official checked them, and paid a high tax proportional to the product. This check was carried out using a chemical process known as "à la coupelle", which is said to be highly accurate. Swiss products, on the other hand, were not subject to these regulations, and were therefore much less expensive than French watches. What's more, the French administration applied testing and inspection duties to unworked, unpolished, and unengraved cases, whereas at the nearby Swiss border, these duties were levied only on finished products, therefore relieved of the burden of engraving.

Difficult mechanization

However, the dominance of Swiss clockmaking was not simply due to administrative differences: the Swiss were far more enterprising and organized than the people of Besançon, and clearly understood that the future of clockmaking lay in technical developments. At the Philadelphia Exhibition in 1877, the Swiss realized that the progress made by American clockmaking could put them in difficulty, and they immediately began to reform their tools to keep up with the times and remain competitive. French and Franche-Comté clockmaking, though concerned by these developments, continued to rely on the manufacturing methods of the past, and postponed the use of new methods in which they had no faith. As proof, an 1880 Chamber of Commerce report: "Machine tools of a certain power are little used (in Besançon); they have not yet been considered indispensable to the progress of the clockmaking industry. We foresee a time when this will not be the case and when factory work will become necessary, and we dread the time when workers will no longer be able to work with their families." The director of the Besançon clockmaking school, Mr. L. Lossier, pleads the case for non-mechanization, as evidenced by a note dating from 1890.

Nevertheless, progress was made in the 1880s with the construction of an astronomical, meteorological, and chronometric observatory, completed between 1883 and 1884. The construction of a chronometric observatory was to align the region with Switzerland in their fierce competition for watch manufacturing. Taking their cue from their neighbors, local clockmakers called for the creation of an independent certifying body, offering a wide range of services including watch testing and local production of accurate time. A chronometric observatory, inspired by those in Geneva and Neuchâtel, was orchestrated by architect Étienne-Bernard Saint-Ginest. The time given by the observatory was posted at the Town Hall, so that local clockmakers could come and take it in the morning.

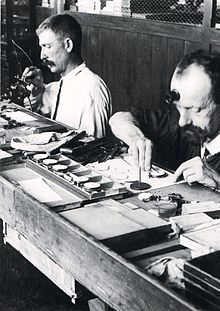

Although the town has had a gold case assembly workshop since 1881, created by the merger of several private firms and equipped with a full range of modern tools on par with those in Switzerland and the US, the case factory is only involved in an independent part of the clockmaking movement, not the watches themselves. Watch assembly still relies too heavily on manual labor compared to competitors, and the use of machines is almost non-existent in the city. The Besançon clockmaking industry continued to manufacture rough metal parts called ébauche, requiring a large workforce to produce the actual movements in a series of twenty or so operations called finissage.

From 1889 onwards, however, the trend in Besançon was reversed: mechanization gradually made its appearance. Movement factories were set up to mechanically manufacture driving parts, drastically reducing the time and manpower required to manufacture Franc-Comtois watches. New kinds of production workshops appeared in the Comtois capital, such as MM. Bloch-Geismar and Cie, which owned workshops for case assemblers in the city, and opened a veritable small factory producing watches from A to Z, without recourse to family labor. Mechanization was no longer marginal, and more and more workshops now had crimping machines, which placed the rubies at very precise points, something a craftsman could not do by hand. This saved considerable time, since the operation performed by the machine no longer required reworking the moving parts to adapt them to the fixed points.

Incomparable expansion

Fortunately, changes in manufacturing processes from 1889 onwards breathed new life into the Besançon industry, which began to catch up with its Swiss neighbor. Then in 1892, legislation became neutral for the two competing countries, since Swiss watches imported from 1894 onwards had to be at least partially subject to the same controls as French products. In 1893, the city of Besançon organized a national, industrial, technical and retrospective exhibition to commemorate the arrival of the Swiss and Mégevand 100 years earlier. An agreement was reached with Russia, which was presented with magnificent clockmaking models from Besançon. In 1901, the magazine La France horlogère defended Besançon's reputation and workforce, and the town reached such heights of popularity in the clockmaking industry that Parisian firms such as Maison Leroy set up shop in the city. The industry took off again at the beginning of the 20th century, with the town producing 635,980 items in 1900, but employing just 3,000 workers by 1910, mainly due to the advent of mechanical engineering. Indeed, even if this number can be significantly increased if we take into account the many workers' wives who work at home "in their spare time", the simplification of manufacturing significantly reduces costs and production time, thus requiring less manpower. Nevertheless, the number of workshops grew steadily in the 1910s and 1920s, with the town boasting around a hundred clockmaking workshops on the eve of the war, including Bloch-Geismar, Sarda, Lévy, Piguet, Ulmann, Kummer and, of course, Lipmann.

At the end of the 19th century, one of the city's finest timepieces was completed: the Besançon Astronomical Clock. Located in Saint-Jean Cathedral, this astronomical clock, built by Auguste-Lucien Vérité in the late 19th century, is considered a masterpiece of its kind. It is made up of 30,000 elements and features 122 interrelated indications, including: hours, dates, seasons, length of day and night, times at 20 locations around the world, number of lunar and solar eclipses, zodiac signs, date of Easter (epact), tide dates and times, solar time, solstice. It took two years of work and three years of improvements to build. It follows on from an astronomical clock by Bernardin, built around 1851–1857, which, complicated and defective, disappeared around 1860. The clock was listed as a historic monument in 1991.

In 1905, a controversy erupted in the town because of the perceived unfair competition from civil servants (letter carriers, teachers, customs officers, country wardens, etc.) who were solicited by watch manufacturers to sell horological products, which put Besançon's clock merchants at a serious disadvantage. In the same year, around a hundred clockmakers in Besançon founded the syndicat des ouvriers horlogers (Clockmakers' Workers' Union), which split into two groups in 1907, with a majority of union members wanting to join the International Federation of Movement Workers, and breaking with the local federation. The remainder, who wished to remain outside the federation, formed a new union, but with so few members that it was incapable of effective action. A union already existed for canmakers, but dissension between the gold and silver canmakers led to its dissolution. In 1907, however, the Union ouvrier de la boîte de montre (watch case workers' union) was formed, bringing together case fitters and manufacturers of pendants. This union was very influential during the strikes against machinery in 1891, 1898, and 1899. Finally, the rest of the profession (engravers, chisellers, guillocheurs, enamellers, etc.) also had their own union, created in 1909. Employers' associations also existed alongside these workers' unions, including the Besançon clockmaker factory, which was a great success with both manufacturers and traders. Other employers' unions existed, such as the Syndicat des Patrons Monteurs de Boxes en Or, the Syndicat des Patrons Monteurs de Boxes en Argent, the Comité de Défense des Fabricants d'Horlogerie du Doubs et Territoire de Belfort and the Comité des Patrons Décorateurs.

The craze for clockmaking training

Since 1801, the Comtois capital has had a small clockmaking apprenticeship workshop for boys, known as Œuvre de Saint-Joseph, located in the Battant district. However, the profession wished to see the establishment of a real school, and although this desire was first expressed in 1833, it was not until 1844 that Abbé Faivre, in response to the community's wishes and the rapid expansion of the clockmaking industry in the city, founded the first school in the convent of the Petites Carmes in Battant. The town's clockmaking community even wrote to the Minister requesting the creation of a clockmaking school, but no response was forthcoming, so in 1862 the municipality founded the École Municipale d'horlogerie, in the former granary (now a music conservatory). Studies began in 1865 with a program of theoretical and vocational training, carefully designed by Georges Sire, Doctor of Science. The school met with great success, winning prizes such as a bronze medal at the 1867 Paris World's Fair, a medal at the 1878 Paris World's Fair, and a grand prize at the 1889 Paris World's Fair. The small provincial school became a national institution, receiving an endowment in 1891 during a visit by President Sadi Carnot. From 1912 to 1944, the École municipale d'horlogerie was governed by an outstanding figure: Louis Trincano, a former graduate of the school who became a clockmaker in the town and secretary of the factory's union, who obtained the de facto nationalization of the establishment in 1921.

In 1923, the project to build a new school was launched, supported in particular by Monsieur Labbé, Director General of Technical Education, who visited Besançon the following year. The site on Avenue Villarceau in the Grette-Butte district was chosen, and the work was entrusted to the architect Guadet, who built the future Lycée Jules Haag. In 1931, the premises housed the school, as well as the Institut de Chronométrie under the direction of Mr. Jules Haag, and a jewelry section created in 1928. The École Nationale d'Horlogerie de Besançon was officially inaugurated on July 2, 1933, by President Albert Lebrun. In 1939, the school became home to the "Bureau des Etudes Horlogères", under the patronage of the Ministry of Technical Education and with the support of the Ministries of Commerce and Industry, the General Council, the City Council, and the trade unions, before becoming the "Comité d'Organisation de l'Industrie de la Montre" after the 1940 debacle, under the aegis of André Donat, a top-level engineer who had transferred from Lip and Trincano. The school expanded at the end of the 1930s, but with the outbreak of war, teaching came to a halt and the school did not resume normal operations until December 1944. The building continued to expand in the 1950s and 1960s, and in 1962 the École Nationale d'Horlogerie celebrated its centenary with General De Gaulle and Jean Minjoz, who said: "Besançon owes much of its industrial development today to the École d'Horlogerie"; a commemorative stamp was issued. Gradually, the school became multi-purpose, moving from watchmaking to microtechnology, electricity and electronics.

The 1930s crisis

The Great Depression hit the city at the end of 1930, and had significant repercussions until 1936. As the city and region depended heavily on Switzerland for basic parts, and that country was one of the first to be hit hard, the repercussions were soon felt in the Comtois capital. The crisis was particularly severe in Besançon, as the majority of the city's companies manufactured small watches, which fell by 46%, while large watches dropped by 18%. By the end of 1931, many companies in Besançon were affected: the Société générale des monteurs de boîtes or, Zenith, Lip and Laudet all had to reduce their staff, as did watch supply companies such as Brunchwing and Nicolet (dials) and Manzoni (watch glasses). In the long term, partial or total unemployment soared, exports and imports dropped considerably, many companies in the sector were jeopardized, and around thirty closed for good between 1931 and 1936. It wasn't until December 1935 that the sector recovered somewhat, and in 1936 the situation returned to almost normal.

From a timid revival to the end of the journey

After World War II, the clockmaking industry remained dominant, but declined from 50% of industrial jobs in 1954 to 35% in 1962, gradually giving way to other booming sectors such as textiles, construction, and the food industry. By 1962, three companies had more than a thousand employees: the clockmaking companies Lip and Kelton-Timex, and the Rhodiacéta textile factory. It was in the Comtois capital that the very first quartz watch saw the light of day.

For Besançon, the 1973 oil crisis was the beginning of an economic depression that devastated its industry and put an abrupt end to its meteoric rise. The development of clockmaking centers in the Far East and fierce competition from Switzerland put Besançon in even greater difficulty. This crisis was first symbolized by the famous Lip affair, which left a lasting mark on the town's history. The company was threatened with downsizing in the spring of 1973, giving rise to a new kind of social struggle based on self-management and provoking a nationwide wave of solidarity that culminated on September 29 with the marche Lip (Lip march), which saw between 80,000 and 100,000 people, from all over France and Europe march through a ville morte (dead city); the procession went from the Jean-Minjoz Hospital in Planoise to the Chamber of Commerce, along the rue de Dole. After a glimpse of an upturn in activity, bankruptcy was unavoidable and Lip disappeared in 1977.

In 1982, the town was struck again by the closure of the Rhodia factory, which left almost 2,000 employees out in the cold, followed shortly afterwards by the difficulties of the Kelton-Timex clockmaking company. In almost twenty years, the town lost almost 10,000 industrial jobs and seems set for a difficult recovery. Thanks in part to the decentralization laws of 1982, the town's industrial vocation was transformed into that of a tertiary center. In 1985, 80% of watches were still produced in the Doubs department.

Reconversion

The town started preparing for reconversion in the 1970s, following the collapse of the clockmaking industry. Clockmaking know-how, which dates back more than two centuries, is being enhanced by conversion to microtechnologies, precision mechanics, and nanotechnologies on a European scale, and to the specific field of time-frequency on a global scale. One area of the city became home to most of the new microtechnology activities: the microtechnology and science park, commonly known as Témis. Established on a 75-hectare site built in the 2000s, the area is home to 150 companies employing over 1,000 people, and features the Témis innovation building, with 6,500 m entirely dedicated to microtechnology, as well as the École nationale supérieure de mécanique et des microtechniques, which trains around 900 students a year. Since then, Besançon has become France's leading center for stamping and micromechanics. The Micronora trade show, held every two years at Micropolis, also contributes to Besançon's influence in the microtechnology sector. Other assets, such as quality of life and heritage, as well as its location on the Rhine-Rhone axis, which is a structuring factor on a European scale, are enabling Besançon to make a fresh start at the beginning of the 21st century.

However, there are still a few clockmaking companies in the city and region, most of which are subcontractors for major Swiss or Parisian brands. Since the early 1990s, they have focused on high-end products, while Asian countries have taken over at the lower end of the market. Comprising two-thirds of the national clockmaking workforce, they are mainly found in the Haut-Doubs region, on or near the Swiss border, as well as a few in the Comtois capital. A large number of Franche-Comté companies produce the majority of watch components (cases, dials, movements, glasses, hands, crowns and bracelets) for Swiss brands with a world-renowned image for quality. This small exodus is having a major impact on the local clockmaking tradition, which is tending to disappear more and more, and has already been severely weakened for decades by the crisis in the sector. To remain competitive, the Franche-Comté clockmaking sector is striving to be a leader in innovation, creativity, responsiveness, and marketing. The presence of the centre technique de l'industrie horlogère (CETEHOR) in Besançon is a valuable asset for keeping abreast of all the technical innovations in the clockmaking sector. Clockmaking companies are constantly looking for ways to diversify into sectors where their expertise is recognized and appreciated, notably in the luxury goods and microtechnology sectors.

Today, the Franc-Comté clockmaking industry represents 89 establishments, 2,119 salaried jobs, 2% of the region's industrial workforce, and 60% of the sector's national workforce (although salaried jobs fell by 29% between 2000 and 2005, with 900 fewer jobs between the two dates), and 85% of companies have fewer than 50 employees. In Besançon, the main clockmaking companies and affiliates are Maty (600 employees, including 450 in Besançon), Cheval frères SAS (300 employees), SMB horlogerie (140 employees), Fralsen (around 100 employees), Breitling Besançon (at least 60 employees), Festina France (46 employees, 700,000 watches produced per year), Sibra (production of leather watch straps, 40 employees) and Universo France (at least 40 employees).

Illustrious clockmaking companies

See also: List of watch manufacturersThe expansion of the clock and watchmaking industry in Besançon has led to a sharp rise in the number of related companies in the city. These included world-renowned companies such as Lip, Yema, Zenith and Maty, as well as smaller factories with workshops employing no more than a few dozen workers. For decades, all these factories have played an essential part in the city's economy, offering a wide range of jobs to the local population. The following is a non-exhaustive list of the city's biggest names in the field of horology.

Major companies

Lip

Lip has long been associated with the town's watchmaking industry. A small workshop founded by Emmanuel Lipmann existed as early as the 1800s, as evidenced by the gift of a chronometer watch to Napoleon I in 1807. But it wasn't until 1867 that Emmanuel's grandson, Ernest Lipmann, opened a full-fledged watch production workshop in the city. The brand officially appeared under the name Lip in 1896, and little by little the family business grew into a full-fledged industrial enterprise. In 1931, Lip SA was founded, employing 350 people; in 1960, the new Lip factory opened in the Palente district, employing over 1,000 people. In 1967, the Swiss trust Ébauches SA bought 33% of Lip's capital, then in 1970 43%, the maximum share authorized at the time; the first workers' mobilizations began in 1968. In 1969, a first downsizing plan failed thanks to the mobilization of employees and unions, and resistance began to grow. After several unsatisfactory redundancy plans and a bankruptcy filing, on June 12, 1973, workers occupied the factory and sold the watches they produced themselves, before the forces of law and order dislodged them on August 14, 1973. The company subsequently recovered with difficulty, but the brand still exists well into the 21st century.

Yema

The town boasts another illustrious company: the Yema brand, founded in the town by Louis Belmont in 1948. In 1952, the workshop produced the first series of all-French automatic chronographs, and in the 1960s was the most exported French brand. By 1961, the company was producing over 300,000 watches a year, topping the 400,000 mark in 1966, before reaching 500,000 watches sold in over fifty countries in 1969. The peak was reached in the mid-to-late 1970s, with a total of 850,000 watches produced in 1976, over a million in 1977 exported to more than sixty countries, and 1,300,000 in 1978. Thereafter, production dropped to just 220,000 watches in 1990, then 100,000 in 2000, before halving in 2005.

Maty

Maty is another famous jewelry brand, founded in 1952 by Gérard Mantion in Besançon. The company's founder, then aged 24, had an original idea for the time: to sell watches by mail order. From a small shop in the Rue Jeanneney in Besançon's capital, he and his wife launched a first catalog featuring twelve watch models for men and women: the Maty company was born. Headquartered on boulevard Kennedy in the Montrapon-Fontaine-Écu district, the company also operates in the city of Belfort, and currently employs around 800 people.

Kelton-Timex (Fralsen)

The former Kelton-Timex factory, now Fralsen, was also one of the city's largest companies. In the 1970s, it employed up to 3,000 people in its factory on boulevard Kennedy, in the Montrapon-Fontaine-Écu district opposite Maty. However, the quartz crisis threatened the company, which experienced numerous difficulties and had to lay off many of its employees: by 1985, only 1,400 remained. The workforce subsequently dwindled even further, to around 200 by 2005, before the relocation of part of the production to China led to the loss of around 150 jobs, bringing the current workforce down to just under a hundred. However, the company seems to be out of the crisis, and is even planning to hire a few new staff.

Small and medium-sized companies

Dodane

The Dodane company was founded in 1857 by Alphonse Dodane and his father-in-law François-Xavier Joubert, just over the border from Switzerland, in a village called La Rasse. The family workshop subsequently moved to Morteau, and on the eve of World War I the company specialized in wartime clockmaking products. In 1929, the factory moved to Besançon, where the brand flourished, producing up to 100,000 watches in 1983. The company is still in business today. The Dodane factory in Besançon was built by Auguste Perret from 1939 to 1943 and listed as a historic monument on June 20, 1986. Today, the building is considered an architectural masterpiece of its kind. The building is made of reinforced concrete with steel beams, and also includes a private formal garden with a swimming pool and tennis court, and was decommissioned in 1994. Located in the Montrapon-Fontaine-Écu district, the Dodane factory's architectural homogeneity is a fitting testimony to Bisont's clockmaking activity.

Zenith

Zenith de Bregille was a subsidiary of the Zenith group from Le Locle, Switzerland. It was established in Besançon to manufacture watch parts and employed up to 150 people, many of whom lived in the area. However, in 1970, Zenith left Besançon and returned to Switzerland, before the premises it occupied were taken over by France-Ébauche as general management. At the time, the company had 400 employees, including 50 in Bregille, and specialized in the design and production of watches, like its predecessor. But it too left Bregille, before in 1994 the building became a temporary courthouse due to the work being carried out in the old court building, and then an annex of the regional council.

Tribaudeau

Tribaudeau was a small, traditional clockmaking company founded in 1876, named after its founder, G. Tribaudeau, and located next to the funicular railway station. With its Trib brand, the company sold its products by mail order. The factory employed around 50 people before it closed in the 1960s. However, thanks to a new owner, the company was able to make a fresh start in the 1980s, particularly with its advertising watches, employing 54 workers by 1985. Today, Trib is France's leading brand of advertising watches, and sells its products throughout Europe.

René Blind

The René Blind company was created and operated from 1955 to 1965 on rue du Funiculaire in Bregille. Employing up to 45 people, this small factory specialized in the manufacture of ladies' watches, marketed through wholesale networks. The company won several CETEHOR (Centre Technique de l'Industrie Horlogère) awards, before disappearing in the face of competition from emerging countries.

Action Horlogerie

Action Horlogerie has been making watches since 1961. They specialize in the production of watches for men, women and children.

Others

Many other small clockmaking workshops also existed in the Bregille area. For example, Jusma watches (later Sifhor), founded by Francis Landry in 1963 as a clockmaker and winegrower, continued until the 1970s, employing up to 40 workers. Other independent clockmakers had their own workshops, such as Père Gauthier, Bossy fils (founded in 1848), whose 4 generations were Xavier Bossy, Léon Bossy, Georges Bossy and Roger Bossy. This company was located at 6 rue des chambrettes (rue Pasteur), then at 9 rue de Lorraine, in the neighborhood of clockmaking workshops, Charlers Wetzel, Gérard Blondeau, Lamoureux. In addition to the clockmaking business, there were also companies specializing in items associated with watches, such as Georges Pargemin, which made leather bracelets, and the M. Matille jewelry store, founded in 1920 and employing up to ten people.

Prominent figures connected with clockmaking in Besançon

- Antide Janvier (1751-1835), from the Jura region, visited the city in 1770, when the municipality, whose attention had been drawn by his previous work, asked him to work on the refurbishment of Cardinal de Granvelle's table clock, made in Augsburg in 1564.

- Laurent Mégevand (1754-1814) Swiss-born watchmaker, founder of Besançon's historic watchmaking industry.

- Auguste-Lucien Vérité (1806-1887), creator of the Besançon astronomical clock, is considered a masterpiece of its kind.

- Emmanuel Lipmann (19th century), a Jew from Besançon, founder of the Lip dynasty.

- Louis-Joseph Fernier (1815-1879), mayor-deputy of Besançon elected in 1871, founder of the Louis Fernier & Frères clockmaking company.

- Louis Duplain (1860-1931), was a self-taught clockmaking poet. A city street bears his name, in the Saint-Ferjeux district, and a statue has been erected near Saint-Jean Cathedral.

Places in Besançon linked to clockmaking

The Musée du Temps

At the end of the nineteenth century, the city of Besançon, in line with the intense activity in the clockmaking industry and in the image of Swiss museums, began to consider the idea of creating a clockmaking museum. Attempts were made to build up collections, and after several difficulties, the partnership of local elected officials and a scientific project brought the project to fruition in 1890. The aim was to combine two municipal collections: the first, from the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie de Besançon, which possessed watches, sundials, hourglasses, etc.; and the second, from the Museum of History (with paintings, engravings, etc.), which was completed in the 1980s with the creation of a department of industrial history, attracting new clockmaking collections. In 1987, the history museum disappeared, to be replaced by the Musée du Temps in the Palais Granvelle, supported by the municipality of Besançon, the European Union, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Research, the region and the département, all of which provided the means to endow the capital of Besançon with a museum unrivaled in Europe.

Lycée Jules Haag

The lycée was built between 1923 and 1933 in the Grette-Butte district. In 2010, the school's administration is working with the Franche-Comté regional council on a rehabilitation program, including the refurbishment of existing buildings and the construction of new ones, as in 2003 to accommodate BTS students and preparatory classes for grandes écoles. A new CDI has also been built, along with a cafeteria and an area for teachers. In 2008, the President of the Regional Council, Marie-Guite Dufay, inaugurated the microtechnology plateau, which has undergone a major redevelopment.

By becoming the Lycée technique d'État Jules Haag in 1978, then the Lycée polyvalent Jules Haag in 1987, the clockmaking school, which conveys its rich technological culture, aligns itself with the other Lycées in Bisont, which are also polyvalent, in its general education function, but retains a certain coloration that sets it apart from the others. The clockmaking school offers a more social alternative, ensuring a professional outlet in the region itself, hence the reputation it has been able to acquire, particularly among the population deeply involved in the city's industrial fabric. When Besançon lost its clockmaking vocation, it became the capitale des microtechniques (capital of microtechnology), and the Lycée Jules Haag played its part in this development.

Architecturally, the Lycée is considered one of the city's finest concrete buildings, notably for the numerous engravings and bas-reliefs adorning its imposing Art Deco façade, and for the astronomical dome on the roof of the building itself.

Besançon clockmaking in the arts

Architecture

In addition to the many books on the city's clockmaking history and the Lip conflict, architectural elements also highlight the importance of this industry to the region. The town's long clockmaking past can be seen in the ten-meter-high clock at the Viotte train station, as well as in the numerous clockmakers scattered throughout the town, mainly in the historic center. It's also not uncommon to see flower arrangements in the town, in the form of clocks.

Comics

In the Asterix comic book series Obélix et Compagnie, a reference to Besançon's clockmaking culture is made by the merchant Uniprix, who sells hourglasses from Vesontio, Besançon's ancient Gallo-Roman name.

Films

Les Lip, l'imagination au pouvoir is a documentary directed by Christian Rouaud, released in 2007. It presents the Lip affair and all its events through the testimonies of the main protagonists of the time, in a historical, social, and political tone, including some archive footage. Unanimously acclaimed by critics for its concept and neutrality, the film pays tribute to this struggle and aims to pass on this page of history to younger generations.

Les Lip or Lip, un été tous ensemble is a documentary film by Dominique Ladoge retracing the great Lip strike. Through the eyes of a 20-year-old employee named Tulipe, the daughter of an Italian immigrant, the film revisits the highlights of the 1970s struggle. In June 2010, production company Jade Production called on all Bisontins to come and take part in a re-enactment of the demonstration in the city's historic center.

Fils de Lip is a documentary film directed by Thomas Faverjon in 2007, telling the story of the second Lip conflict through the testimonies of the "voiceless" (all those who were never heard from). It presents another Lip struggle in a company that has filed for bankruptcy, but remains perfectly profitable in terms of both machines and workers. However, no buyer was interested, due to the economic and political elite of the time, who wanted to sanction the revolution of the first conflict. It's a new way of looking at these workers, who aren't experiencing the glory days of the previous struggle, but bitter repression.

Monique, Lip I and La marche de Besançon, Lip II are two documentaries about the Lip conflict made by Carole Roussopoulos in August 1973. In the first documentary, we see scenes filmed at the time, where striking workers express their points of view and in particular in the person of a particularly highlighted employee: Monique Piton, who explains her vision of the conflict with enthusiasm and lucidity; she narrates the course of the occupation of the factory by the police, the four months of fighting, the place of women in this struggle, what she learned, and also criticizes the role of television and the media. The second documentary, also based on period footage, looks back at the Lip march on September 29, 1973.

Appendix

Related articles

External links

- Lycée Jules Haag official website archive

- Official website of the École nationale supérieure de mécanique et des microtechniques de Besançon archive

Bibliography

Books devoted entirely to clockmaking in Besançon

- George Mégnin, Naissance, développement et situation actuelle de l'industrie horlogère à Besançon..., J. Millot et cie. 1909, 300 p.

- Jacques Boyer, "Les trois piliers techniques de l'horlogerie française", La Nature, no 2908, July 1933, pp. 75–80 (read online archive)

- Louis Trincano, "Pages d'Histoire de l'Industrie Horlogère", Annales Françaises de Chronométrie, no vol. 14, September 1944, pp. 175–210 (read online archive)

- Viviane Isambert-Jamati, L'industrie horlogère dans la région de Besançon : étude sociologique, Presses universitaires de France, 1955, 116 p.

- Edmond Maire and Charles Piaget, Lip 73, Éditions du Seuil, 1973, 138 p.

- Michel Cordillot, La Naissance du mouvement ouvrier à Besançon: la Première Internationale, 1869-1872, Presses Univ. Franche-Comté, 1990, 83 p.

- Jean-Luc Mayaud and Joëlle Mauerhan, Besançon horloger, 1793–1914, Musée du temps de Besançon, 1994, 124 p.

- Éveline Toillon, Besançon ville horlogère, Joué-lès-Tours, A. Sutton, coll. "Parcours et labeurs", 2000, 126 p. ISBN 978-2-84253-474-5, OCLC 468594904, BNF 37642154).

- Jean Divo, L'affaire Lip et les catholiques de Franche-Comté : Besançon, 17 avril 1973-29 janvier 1974, Yens-sur-Morges, Éditions Cabedita, 2003, 200 p. ISBN 2-88295-389-5

- Jean Raguénès, De mai 68 à LIP : un Dominicain au cœur des luttes, KARTHALA Editions, 2008, 288 p. ISBN 978-2-8111-0001-8 and 2-8111-0001-6, read online archive)

Books featuring clockmaking in Besançon

- Claude Fohlen, Revue chronométrique, Volume 5, Chambre Syndicale de l'horlogerie de Paris, 1864, 672 p.

- Pierre Daclin, La Crise des années 30 à Besançon, Les Belles lettres, 1968, 136 p.

- Jean-Pierre Gavignet and Lyonel Estavoyer, Besançon autrefois, Le Coteau, Horvath, 1989, 175 p. ISBN 2-7171-0685-5

- Claude Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, tome 2, Besançon, Cêtre, 1994, 824 p. ISBN 2-901040-27-6

- Jean-Claude Daumas, La mémoire de l'industrie: De l'usine au patrimoine, Presses Univ. Franche-Comté, 2006, 426 p.

- Hector Tonon et al., Mémoires de Bregille (2nd edition), Besançon, Cêtre, December 2009, 312 p. ISBN 978-2-87823-196-0

References

- ^ Historique de l'horloge comtoise sur horlogerie-comtoise.fr (accessed on October 26, 2010.).

- ^ Pays et gens de France : Bourgogne Franche-Comté, Larousse, 1985, page 18.

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 74.

- ^ Laurent Megevand sur Racinescomtoises.net (accessed on September 7, 2010.).

- Bibliographie franc-comtoise 1980-1990, page 52.

- ^ Les Suisses et l'horlogerie à Besançon, sur Migrations.Besançon.fr (accessed on September 7, 2010.).

- Besançon sur le site officiel du Larousse (accessed on November 11, 2010.).

- ^ Le musée du Temps sur le site officiel de la ville de Besançon (accessed on October 25, 2010.).

- ^ C. Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, t. II, p. 251-253.

- Laurent Megevand sur le site officiel de la ville du Locle Archived 2010-12-23 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on September 7, 2010.).

- ^ L'enseignement horloger à Besançon sur Racines-Comtoises.net (accessed on October 25, 2010.).

- ^ Histoire de l'entreprise Lip sur montres-lip.com Archived 2010-10-02 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on October 25, 2010.).

- ^ La mesure du temps, montres et horloges, by Éliane Maingot, published in Miroir de l’histoire, 1970, p. 65-79 (brochure).

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 75.

- ^ C. Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, t. II, p. 378

- L'épopée de la mesure du temps, Le journal de Carrefour, décembre 1999, numéro 58.

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 77.

- Jacques Borgé and Nicolas Viasnoff, Archives de la Franche-Comté, 1996, page 33. "One of the first conditions of prosperity for an industry is that the recruitment of workers be easy, in other words, that the industry be remunerative for the worker. This doesn't mean that the best industry will be the one that pays the highest wages; but it will certainly be the one that allows him a certain freedom to exercise his intelligence and free will as a man, and to look after his children's education. Following this idea, we can affirm that there is no greater benefit for the worker than the industry he can practice with his family. This is true for all workers in general, and it is especially true for our town of Besançon, where the watchmaking industry has been pushed further than anywhere else in terms of the division of labor and the exercise of family industry. This is clear from the history of watchmaking in our country, and is an indication that, more than anywhere else, our mores and our character are particularly well suited to this family work, in which the father can engage while remaining in constant contact with his family, in which the mother can also help, during the few moments left to her by the care of the household, and in which the children themselves can, when they have reached the right age, contribute here and there with their little fingers and their fresh intelligence. For some years now, our watchmaking industry has been lagging behind, and it is fashionable to say today that we can only make up lost ground by creating large factories similar to those in Switzerland and the USA. I have no intention of criticizing large factories; but I did want to see if it wasn't possible to achieve the goal by means of our own processes, more in line with our own morals and better suited to the principles we set out above to improve the social status of the worker. After studying the question very seriously, I became convinced that there was nothing to prevent the creation of a certain number of partial production workshops in our country, as an advantageous replacement for factory work, while at the same time offering the immense advantage of dispersing capital (not putting all your eggs in one basket), and encouraging its investment in the form of small, easy-to-monitor limited partnerships, which are safer and more profitable than shares in a large factory. The work, distributed in a number of small units, will be able to benefit from improvements in tooling, just as well as a large factory, and even better in some cases. It's true that the dispersal of work leads to some loss of time, which inevitably translates into higher cost prices; but this is a minor inconvenience, which is redeemed by so many advantages that it eventually disappears completely."

- ^ L'observatoire de Besançon sur le site officiel du ministère de la Culture (accessed on October 25, 2010.).

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 78.

- C. Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, t. II, p. 379

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 79.

- ^ Mémoires de Bregille, 2009, page 240.

- ^ R. Goudey : Horloge astronomique de Saint-Jean de Besançon, 1909, 30 pages.

- Notice no PM25001538, base Palissy, ministère français de la Culture.

- Jacques Borgé and Nicolas Viasnoff, Archives de la Franche-Comté, 1996, page 161 (rapport de M.Fernier au Congrès de la Ligue contre la concurrence déloyale, Besançon, 1905.) "In recent years, this competition has taken on disastrous proportions, due to the fact that today all small civil servants are solicited by factories to act as intermediaries with the public. Cleverly-written leaflets tell them how little trouble it is to place watches and jewelry, generally at low prices, in their homes. The promised benefits quickly led many of them to seek out these easy-earning commercial operations. It's more than obvious that a trader of this nature, in addition to the esteem he enjoys as a result of his public functions, has the advantage over genuine traders of not having to pay patents, of not having to keep any goods in stock, and of being exempt from the overheads that weigh so heavily on regular trade. So it's not surprising that goods delivered under these conditions are more often than not at lower prices than those generally charged by genuine traders. Competition from civil servants is disastrous for us on two counts: firstly, because of the extent to which it has taken on in recent years, where there is no longer a single commune in France without a letter carrier, teacher, customs officer or village warden who does not practice it with varying degrees of success; and secondly, because of the exceptionally favorable conditions in which it is practiced. So it's not too far-fetched to say that today, one third of all watches sold in France are sold through licensed watchmakers."

- Besançon autrefois, page 80.

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 81.

- ^ Besançon autrefois, page 82.

- ^ La crise des années 1930 à Besançon, page 34 à 53.

- C. Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, t. II, p. 518.

- (fr) Michel Chevalier et Pierre Biays, "Chronique comtoise", Revue Géographique de l'Est, vol. 1, no 1, 1961, p. 66 (DOI 10.3406/rgest.1961.1766, read online, accessed on August 22, 2020)

- C. Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, t. II, p. 519.

- ^ La Route des Communes du Doubs, Éditions C'Prim, 386 pages, 2010, page 88.

- ^ C. Fohlen, Histoire de Besançon, t. II, p. 570-571.

- ^ La marche Lip sur Lepost.fr Archived 2010-12-19 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on November 9, 2010.).

- La sage des montres Lip sur Linternaute.com Archived 2016-09-24 at the Wayback Machine (consulté le 10 novembre 2010).

- De mai 68 à LIP: un Dominicain au cœur des luttes, page 178.

- "Les Prés-de-Vaux, cœur de l’activité ouvrière bisontine", article de l'Hebdo de Besançon of May 30, 2007.

- Pays et gens de France : Bourgogne Franche-Comté, Larousse, 1985, page 17.

- ^ Historique de Témis sur le site officiel du technopôle Archived 2010-11-26 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on November 4, 2010.).

- ^ La Route des Communes du Doubs, Éditions C'Prim, 386 pages, 2010, page 78.

- Présentation de l'ENSMM sur le site officiel de l'établissement Archived 2012-04-12 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on November 4, 2010).

- Besançon et la microtechnologie sur le site officiel de la ville (accessed on November 4, 2010.).

- ^ L'horlogerie et les microtechniques en Franche-Comté sur le site de l'INSEE (accessed on November 9, 2010.).

- ^ Les 100 plus grandes entreprises de Besançon sur le site de l'Express (accessed on November 9, 2010.).

- "SMB Horlogerie se tourne vers la montre de joaillerie". La Tribune. 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2024-08-23.

- ^ Horlogerie : Fralsen remonte le temps, sur MaCommune.info Archived 2010-04-09 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on 26 October 2010).

- ^ Edmond Maire and Charles Piaget, Lip 73, Éditions du Seuil, 1973, page 7.

- ^ Histoire de l'entreprise Yema, sur montres-de-luxe.com (accessed on October 25, 2010).

- ^ Fralsen relocalise quelques pièces, sur France 3 Bourgogne Franche-Comté (accessed on 26 October 2010).

- Visite de Fred Olsen, PDG de Fralsen, à la filiale de Besançon, sur le site de l'INA (accessed on October 26, 2010.).

- ^ Histoire de l'horlogerie Dodane sur le site officiel de l'entreprise (accessed on October 26, 2010.).

- ^ Notice no PA00101613, base Mérimée, ministère français de la Culture.

- L'usine des horlogeries Dodane sur le site de l'INA (accessed on October 25, 2010.).

- Histoire de l'horlogerie Zenith sur Horlogerie-Suisse.com Archived 2010-11-23 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on July 30, 2010.).

- ^ Historique de la marque Trib sur le site officiel de l'entreprise Archived 2010-01-25 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on November 11, 2010.).

- ^ Mémoires de Bregille, 2009, page 241.

- Le développement de l'entreprise d'horlogerie Trib à Besançon, sur le site de l'INA (accessed on November 11, 2010.).

- Montre Action sur http://www.sav.support/

- Jean-Paul Colin, Franche-Comté, 2002, 319 pages - page 205.

- Besançon: école d'horlogerie, sur France 3 Bourgogne Franche-Comté (accessed on October 26, 2010.).

- Les Lip, l'imagination au pouvoir sur le site officiel du film (accessed on November 11, 2010.).

- "Lip, un été tous ensemble" : les Bisontins appelés à manifester, sur MaCommune.info Archived 2010-05-26 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on November 7, 2010.).

- ^ Présentation du film Fils de Lip sur Autourdu1ermai.fr (accessed on November 14, 2010.).

- ^ Le film Les Lip, l'imagination au pouvoir sur Objectif-cinema.com (accessed on November 14, 2010.).

- Le film Monique, Lip I sur Evene.fr (accessed on November 14, 2010.).