| This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2022) |

A panoramic view over the southernmost districts of Helsinki from Hotel Torni. The Helsinki Old Church and its surrounding park are seen in the foreground, while the towers of St. John's Church (near centre) and Mikael Agricola Church (right) can be seen in the middle distance, backdropped by the Gulf of Finland. A panoramic view over the southernmost districts of Helsinki from Hotel Torni. The Helsinki Old Church and its surrounding park are seen in the foreground, while the towers of St. John's Church (near centre) and Mikael Agricola Church (right) can be seen in the middle distance, backdropped by the Gulf of Finland. | |

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| Fiscal year | calendar year |

| Trade organisations | EU, WTO and OECD |

| Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | 5,550,066 (1 March 2023) |

| GDP |

|

| GDP rank | |

| GDP growth |

|

| GDP per capita |

|

| GDP per capita rank | |

| GDP by sector |

|

| Inflation (CPI) | 1.6% (2022 est.) |

| Population below poverty line | 15.8% at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE, 2023) |

| Gini coefficient | 26.6 low (2023) |

| Human Development Index |

|

| Corruption Perceptions Index | |

| Labour force |

|

| Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

| Average gross salary | €3,974 monthly (2023) |

| Average net salary | €2,366 monthly (2023) |

| Main industries | metals and metal products, electronics, machinery and scientific instruments, shipbuilding, pulp and paper, foodstuffs, chemicals, textiles, clothing |

| External | |

| Exports | €98.47 billion (2021 est.) |

| Export goods | electrical and optical equipment, machinery, transport equipment, paper and pulp, chemicals, basic metals; timber |

| Main export partners |

|

| Imports | €97.88 billion (2021 est.) |

| Import goods | foodstuffs, petroleum and petroleum products, chemicals, transport equipment, iron and steel, machinery, computers, electronic industry products, textile yarn and fabrics, grains |

| Main import partners | |

| FDI stock |

|

| Current account | $1.806 billion (2017 est.) |

| Gross external debt | $150.6 billion (31 December 2016 est.) |

| Public finances | |

| Government debt |

|

| Budget balance |

|

| Revenues | 52.2% of GDP (2019) |

| Expenses | 53.3% of GDP (2019) |

| Economic aid |

|

| Credit rating | AAA (Domestic) AAA (Foreign) AA+ (T&C Assessment) (Standard & Poor's) Scope: AA+ Outlook: Stable |

| Foreign reserves | $10.51 billion (31 December 2017 est.) |

| All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Finland is a highly industrialised, mixed economy with a per capita output similar to that of western European economies such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The largest sector of Finland's economy is its service sector, which contributes 72.7% to the country's gross domestic product (GDP); followed by manufacturing and refining at 31.4%; and concluded with the country's primary sector at 2.9%. Among OECD nations, Finland has a highly efficient and strong social security system; social expenditure stood at roughly 29% of GDP.

Finland's key economic sector is manufacturing. The largest industries are electronics (21.6% - very old data), machinery, vehicles and other engineered metal products (21.1%), forest industry (13.1%), and chemicals (10.9%). Finland has timber and several mineral and freshwater resources. Forestry, paper factories, and the agricultural sector (on which taxpayers spend around 2 billion euro annually) are politically sensitive to rural residents. The Helsinki metropolitan area generates around a third of GDP.

In a 2004 OECD comparison, high-technology manufacturing in Finland ranked second largest in the world, after Ireland. Investment was below the expected levels. The overall short-term outlook was good and GDP growth has been above many of its peers in the European Union. Finland has the 4th largest knowledge economy in Europe, behind Sweden, Denmark and the UK. The economy of Finland tops the ranking of the Global Information Technology 2014 report by the World Economic Forum for concerted output between the business sector, the scholarly production and the governmental assistance on information and communications technology.

Finland is highly integrated in the global economy, and international trade represents a third of the GDP. Trade with the European Union represents 60% of the country's total trade. The largest trade flows are with Germany, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands and China. The trade policy is managed by the European Union, where Finland has traditionally been among the free trade supporters, except for agriculture. Finland is the only Nordic country to have joined the Eurozone; Denmark and Sweden have retained their traditional currencies, whereas Iceland and Norway are not members of the EU at all. Finland has been ranked seventh in the Global Innovation Index of 2023, making it the seventh most innovative country down from 2nd in 2018.

History

Being geographically distant from Western and Central Europe in relation to other Nordic countries, Finland struggled behind in terms of industrialization apart from the production of paper, which partially replaced the export of timber solely as a raw material towards the end of the nineteenth century. But as a relatively poor country, it was vulnerable to shocks to the economy such as the great famine of 1867–1868, which killed around 15% of the country's population. Until the 1930s, the Finnish economy was predominantly agrarian and, as late as the 1950s, more than half the population and 40% of output were still in the primary sector.

After World War II

While nationalization committees were set up in France and the United Kingdom, Finland avoided nationalizations. Finnish industry recovered quickly after the Second World War. By the end of 1946, industrial output had surpassed pre-war numbers. In the immediate post-war period of 1946 to 1951, Finnish industry continued to grow rapidly. Many factors contributed to the rapid industrial growth. The payment of war reparations were largely paid in manufactured products. The devaluation of currency in 1945 and 1949, which made the US dollar rise by 70% against the Finnish markka, and thus boosted exports to the West. This helped with rebuilding the country and increased demand for Finnish industrial products. In 1951, the Korean War boosted Finnish exports. Finland practiced an active exchange rate policy. Devaluation was used several times to raise the competitiveness of the Finnish exporting industries.

Between 1950 and 1975, Finland's industry was at the mercy of international economic trends. The fast industrial growth in 1953-1955 was followed by a period of more moderate growth, starting in 1956. The causes for the deceleration of growth were the general strike of 1956, as well as weakened export trends and easing of the strict regulation of Finland's foreign trade in 1957. These events compelled Finnish industry to compete against ever toughening international challengers. An economic recession brought industrial output down by 3.4% in 1958. Industry, however, recovered quickly during the international economic boom that followed the recession. One reason for this was the devaluation of the Finnish markka, which increased the value of the US dollar by 39% against the Finnish markka.

The international economy was stable in the 1960s. This trend can be seen in Finland as well, where steady growth of industrial output could be seen throughout the decade.

After failed experiments with protectionism, Finland eased some restrictions and signed a free trade agreement with the European Community in 1973. This made Finnish markets more competitive.

Finland's industrial output declined in 1975. The decline was caused by the free trade agreement that was made between Finland and the European Community in 1973. The agreement subjected Finnish industry to ever toughening international competition. Finnish exports to the west decreased. In 1976 and 1977, the growth in industrial output was almost zero. In 1978, it swung back towards a strong growth. In 1978 and 1979, Finnish industrial output grew at an above average rate. The stimuli for this were three devaluations of Finnish markka, which lowered value of the markka by a total of 19%. Impacts from the global Oil Crisis on Finnish industry were alleviated by Finland's bilateral trade with the Soviet Union.

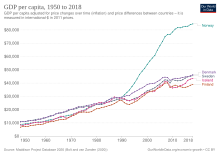

Local education markets expanded. An increasing number of Finns went to study abroad in the United States and in Western Europe. These students later returned to Finland, bringing back useful and advanced professional skills. There was quite a common pragmatic credit and investment cooperation between the state and Finnish corporations. It raised suspicion in the populace, due to support for capitalism and free trade from the populace. However, the Finnish communist party (Finnish People's Democratic League) received 23.2% of the votes in the 1958 parliamentary elections. Savings rates in Finland hovered among the world's highest, at around 8%, all the way to the 1980s. In the beginning of the 1970s, Finland's GDP per capita reached the level of Japan and the UK. Finland's economic development was similar to some export-led Asian countries. The official policy of neutrality enabled Finland to trade both with Western and Comecon markets. Significant bilateral trade was conducted with the Soviet Union, but this was not allowed to grow into a dependence.

Liberalization

Like other Nordic countries, Finland has liberalized its system of economic regulation since late 1980s. The financial and product market regulations were modified. Some state enterprises were privatized and some tax rates were altered. In 1991, the Finnish economy fell into a severe recession. This was caused by a combination of economic overheating (largely due to a change in the banking laws in 1986 which made credit much more accessible), depressed markets with key trading partners (particularly the Swedish and Soviet markets), as well as in the local markets. Slow growth with other trading partners, and the disappearance of the Soviet bilateral trade had its effects. The stock market and the Finnish housing market decreased by 50% in value. The growth in the 1980s was based on debt, and when the defaults began rolling in, GDP declined by 13%. Unemployment increased from almost full employment to one fifth of the workforce. The crisis was amplified by the trade unions' initial opposition to any reforms. Politicians struggled to cut spending and the public debt doubled to around 60% of GDP. Much of the economic growth in the 1980s was based on debt financing. Debt defaults led to a savings and loan crisis. Over 10 billion euros were used to bail out failing banks, which led to a banking sector consolidation. After devaluations, the depression bottomed out in 1993.

European Union

Finland joined the European Union in 1995. The central bank was given an inflation-targeting mandate until Finland joined the euro zone. The growth rate has since been one of the highest of the OECD countries. Finland has topped many indicators of national performance.

Finland was one of the 11 countries joining the third phase of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union. Finland adopted the euro as the country's currency on 1 January 1999. The national currency markka (FIM) was withdrawn from circulation, and replaced by the euro (EUR) at the beginning of 2002.

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2017. Inflation under 2% is in green. Estimates begin after 2021.

| Year | GDP (in Bil. Euro) |

GDP per capita (in Euro) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$ nominal) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in%) |

Unemployment (in%) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 33.7 | 7,059 | 45.5 | 53.7 | 5.3% | 10.9% | ||

| 1981 | ||||||||

| 1982 | ||||||||

| 1983 | ||||||||

| 1984 | ||||||||

| 1985 | ||||||||

| 1986 | ||||||||

| 1987 | ||||||||

| 1988 | ||||||||

| 1989 | ||||||||

| 1990 | ||||||||

| 1991 | ||||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | n/a | |||||||

| 2023 | n/a | |||||||

| 2024 | n/a | |||||||

| 2025 | n/a | |||||||

| 2026 | n/a | |||||||

| 2027 | n/a | |||||||

| 2028 | n/a |

Agriculture

Main article: Agriculture in Finland

Finland's climate and soils make growing crops a particular challenge. The country lies between 60° and 70° north latitude - as far north as Alaska - and has severe winters and relatively short growing seasons that are sometimes interrupted by frosts. However, because the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift Current moderate the climate, and because of the relatively low elevation of the land area, Finland contains half of the world's arable land north of 60° north latitude. In response to the climate, farmers have relied on quick-ripening and frost-resistant varieties of crops. Most farmland had originally been either forest or swamp, and the soil had usually required treatment with lime and years of cultivation to neutralise excess acid and to develop fertility. Irrigation was generally not necessary, but drainage systems were often needed to remove excess water.

Until the late nineteenth century, Finland's isolation required that most farmers concentrate on producing grains to meet the country's basic food needs. In the fall, farmers planted rye; in the spring, southern and central farmers started oats, while northern farmers seeded barley. Farms also grew small quantities of potatoes, other root crops, and legumes. Nevertheless, the total area under cultivation was still small. Cattle grazed in the summer and consumed hay in the winter. Essentially self-sufficient, Finland engaged in very limited agricultural trade.

This traditional, almost autarkic, production pattern shifted sharply during the late nineteenth century, when inexpensive imported grain from Russia and the United States competed effectively with local grain. At the same time, rising domestic and foreign demand for dairy products and the availability of low-cost imported cattle feed made dairy and meat production much more profitable. These changes in market conditions induced Finland's farmers to switch from growing staple grains to producing meat and dairy products, setting a pattern that persisted into the late 1980s.

In response to the agricultural depression of the 1930s, the government encouraged domestic production by imposing tariffs on agricultural imports. This policy enjoyed some success: the total area under cultivation increased, and farm incomes fell less sharply in Finland than in most other countries. Barriers to grain imports stimulated a return to mixed farming, and by 1938 Finland's farmers were able to meet roughly 90% of the domestic demand for grain.

The disruptions caused by the Winter War and the Continuation War caused further food shortages, especially when Finland ceded territory, including about one-tenth of its farmland, to the Soviet Union. The experiences of the depression and the war years persuaded the Finns to secure independent food supplies to prevent shortages in future conflicts.

After the war, the first challenge was to resettle displaced farmers. Most refugee farmers were given farms that included some buildings and land that had already been in production, but some had to make do with "cold farms," that is, land not in production that usually had to be cleared or drained before crops could be sown. The government sponsored large-scale clearing and draining operations that expanded the area suitable for farming. As a result of the resettlement and land-clearing programs, the area under cultivation expanded by about 450,000 hectares, reaching about 2.4 million hectares by the early 1960s. Finland thus came to farm more land than ever before, an unusual development in a country that was simultaneously experiencing rapid industrial growth.

During this period of expansion, farmers introduced modern production practices. The widespread use of modern inputs—chemical fertilisers and insecticides, agricultural machinery, and improved seed varieties—sharply improved crop yields. Yet the modernisation process again made farm production dependent on supplies from abroad, this time on imports of petroleum and fertilisers. By 1984 domestic sources of energy covered only about 20% of farm needs, while in 1950 domestic sources had supplied 70% of them. In the aftermath of the oil price increases of the early 1970s, farmers began to return to local energy sources such as firewood. The existence of many farms that were too small to allow efficient use of tractors also limited mechanisation. Another weak point was the existence of many fields with open drainage ditches needing regular maintenance; in the mid-1980s, experts estimated that half of the cropland needed improved drainage works. At that time, about 1 million hectares had underground drainage, and agricultural authorities planned to help install such works on another million hectares. Despite these shortcomings, Finland's agriculture was efficient and productive—at least when compared with farming in other European countries.

Forestry

Forests play a key role in the country's economy, making it one of the world's leading wood producers and providing raw materials at competitive prices for the crucial wood processing industries. As in agriculture, the government has long played a leading role in forestry, regulating tree cutting, sponsoring technical improvements, and establishing long-term plans to ensure that the country's forests continue to supply the wood-processing industries.

Finland's wet climate and rocky soils are ideal for forests. Tree stands do well throughout the country, except in some areas north of the Arctic Circle. In 1980 the forested area totaled about 19.8 million hectares, providing 4 hectares of forest per capita—far above the European average of about 0.5 hectares. The proportion of forest land varied considerably from region to region. In the central lake plateau and in the eastern and northern provinces, forests covered up to 80% of the land area, but in areas with better conditions for agriculture, especially in the southwest, forests accounted for only 50 to 60% of the territory. The main commercial tree species—pine, spruce, and birch—supplied raw material to the sawmill, pulp, and paper industries. The forests also produced sizable aspen and elder crops.

The heavy winter snows and the network of waterways were used to move logs to the mills. Loggers were able to drag cut trees over the winter snow to the roads or water bodies. In the southwest, the sledding season lasted about 100 days per year; the season was even longer to the north and the east. The country's network of lakes and rivers facilitated log floating, a cheap and rapid means of transport. Each spring, crews floated the logs downstream to collection points; tugs towed log bundles down rivers and across lakes to processing centers. The waterway system covered much of the country, and by the 1980s Finland had extended roadways and railroads to areas not served by waterways, effectively opening up all of the country's forest reserves to commercial use.

Forestry and farming were closely linked. During the twentieth century, government land redistribution programmes had made forest ownership widespread, allotting forestland to most farms. In the 1980s, private farmers controlled 35% of the country's forests; other persons held 27%; the government, 24%; private corporations, 9%; and municipalities and other public bodies, 5%. The forestlands owned by farmers and by other people—some 350,000 plots—were the best, producing 75 to 80% of the wood consumed by industry; the state owned much of the poorer land, especially that in the north.

The ties between forestry and farming were mutually beneficial. Farmers supplemented their incomes with earnings from selling their wood, caring for forests, or logging; forestry made many otherwise marginal farms viable. At the same time, farming communities maintained roads and other infrastructure in rural areas, and they provided workers for forest operations. Indeed, without the farming communities in sparsely populated areas, it would have been much more difficult to continue intensive logging operations and reforestation in many prime forest areas.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has carried out forest inventories and drawn up silvicultural plans. According to surveys, between 1945 and the late 1970s foresters had cut trees faster than the forests could regenerate them. Nevertheless, between the early 1950s and 1981, Finland was able to boost the total area of its forests by some 2.7 million hectares and to increase forest stands under 40 years of age by some 3.2 million hectares. Beginning in 1965, the country instituted plans that called for expanding forest cultivation, draining peatland and waterlogged areas, and replacing slow-growing trees with faster-growing varieties. By the mid-1980s, the Finns had drained 5.5 million hectares, fertilized 2.8 million hectares, and cultivated 3.6 million hectares. Thinning increased the share of trees that would produce suitable lumber, while improved tree varieties increased productivity by as much as 30%.

Comprehensive silvicultural programmes had made it possible for the Finns simultaneously to increase forest output and to add to the amount and value of the growing stock. By the mid-1980s, Finland's forests produced nearly 70 million cubic meters of new wood each year, considerably more than was being cut. During the postwar period, the annual cut increased by about 120% to about 50 million cubic meters. Wood burning fell to one-fifth the level of the immediate postwar years, freeing up wood supplies for the wood-processing industries, which consumed between 40 million and 45 million cubic meters per year. Indeed, industry demand was so great that Finland needed to import 5 million to 6 million cubic meters of wood each year.

To maintain the country's comparative advantage in forest products, Finnish authorities moved to raise lumber output toward the country's ecological limits. In 1984 the government published the Forest 2000 plan, drawn up by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. The plan aimed at increasing forest harvests by about 3% per year, while conserving forestland for recreation and other uses. It also called for enlarging the average size of private forest holdings, increasing the area used for forests, and extending forest cultivation and thinning. If successful, the plan would make it possible to raise wood deliveries by roughly one-third by the end of the twentieth century. Finnish officials believed that such growth was necessary if Finland was to maintain its share in world markets for wood and paper products.

Industry

Since the 1990s, Finnish industry, which for centuries had relied on the country's vast forests, has become increasingly dominated by electronics and services, as globalization led to a decline of more traditional industries. Outsourcing resulted in more manufacturing being transferred abroad, with Finnish-based industry focusing to a greater extent on R&D and hi-tech electronics.

Electronics

The Finnish electronics and electrotechnics industry relies on heavy investment in R&D, and has been accelerated by the liberalisation of global markets. Electrical engineering started in the late 19th century with generators and electric motors built by Gottfried Strömberg, now part of the ABB. Other Finnish companies – such as Instru, Vaisala and Neles (now part of Metso) - have succeeded in areas such as industrial automation, medical and meteorological technology. Nokia was once a world leader in mobile telecommunications.

Metals, engineering and manufacturing

Finland has an abundance of minerals, but many large mines have closed down, and most raw materials are now imported. For this reason, companies now tend to focus on high added-value processing of metals. The exports include steel, copper, chromium, gold, zinc and nickel, and finished products such as steel roofing and cladding, welded steel pipes, copper pipe and coated sheets. Outokumpu is known for developing the flash smelting process for copper production and stainless steel.

In 2019, the country was the world's 5th largest producer of chromium, the 17th largest world producer of sulfur and the 20th largest world producer of phosphate

With regard to vehicles, the Finnish motor industry consists mostly of manufacturers of tractors (Valtra, formerly Valmet tractor), forest machines (f.ex. Ponsse), military vehicles (Sisu, Patria), trucks (Sisu Auto), buses and Valmet Automotive, a contract manufacturer, whose factory in Uusikaupunki produces Mercedes-Benz cars. Shipbuilding is an important industry: the world's largest cruise ships are built in Finland; also, the Finnish company Wärtsilä produces the world's largest diesel engines and has market share of 47%. In addition, Finland also produces train rolling stock.

The manufacturing industry is a significant employer of about 400,000 people.

Mining

- Ahmavaara mine (Gold, copper, nickel)

- Koivu mine (Titanium)

- Konttijärvi mine (Gold, copper, nickel)

- Mustavaara mine (Vanadium)

- Portimo mine (Gold)

- Sokli mine (Phosphates)

- Suhanko mine (Gold, copper, nickel)

Chemical industry

The chemical industry is one of the Finland's largest industrial sectors with its roots in tar making in the 17th century. It produces an enormous range of products for the use of other industrial sectors, especially for forestry and agriculture. In addition, its produces plastics, chemicals, paints, oil products, pharmaceuticals, environmental products, biotech products and petrochemicals. In the beginning of this millennium, biotechnology was regarded as one of the most promising high-tech sectors in Finland. In 2006 it was still considered promising, even though it had not yet become "the new Nokia".

Pulp and paper industry

Forest products has been the major export industry in the past, but diversification and growth of the economy has reduced its share. In the 1970s, the pulp and paper industry accounted for half of Finnish exports. Although this share has shrank, pulp and paper is still a major industry with 52 sites across the country. Furthermore, several of large international corporations in this business are based in Finland. Stora Enso and UPM were placed No. 1 and No. 3 by output in the world, both producing more than ten million tons. M-real and Myllykoski also appear on the top 100 list.

Energy industry

Finland's energy supply is divided as follows: nuclear power 26%, net imports 20%, hydroelectric power 16%, combined production district heat 18%, combined production industry 13%, condensing power 6%. One half of all the energy consumed in Finland goes to industry, one fifth to heating buildings and one fifth to transport. Lacking indigenous fossil fuel resources, Finland has been an energy importer. This might change in the future since Finland is currently building its fifth nuclear reactor, and approved building permits for its sixth and seventh ones. There are some uranium resources in Finland, but to date no commercially viable deposits have been identified for exclusive mining of uranium. However, permits have been granted to Talvivaara to produce uranium from the tailings of their nickel-cobalt mine.

Companies

See also: List of largest companies in Finland

Notable companies in Finland include Nokia, the former market leader in mobile telephony; Stora Enso, the largest paper manufacturer in the world; Neste Oil, an oil refining and marketing company; UPM-Kymmene, the third largest paper manufacturer in the world; Aker Finnyards, the manufacturer of the world's largest cruise ships (such as Royal Caribbean's Freedom of the Seas); Rovio Mobile, video game developer most notable for creating Angry Birds; KONE, a manufacturer of elevators and escalators; Wärtsilä, a producer of power plants and ship engines; and Finnair, the largest Helsinki-Vantaa based international airline. Additionally, many Nordic design firms are headquartered in Finland. These include the Fiskars owned Iittala Group, Artek a furniture design firm co-created by Alvar Aalto, and Marimekko made famous by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Finland has sophisticated financial markets comparable to the UK in efficiency. Though foreign investment is not as high as some other European countries, the largest foreign-headquartered companies included names such as ABB, Tellabs, Carlsberg and Siemens.

Around 70-80% of the equity quoted on the Helsinki Stock Exchange are owned by foreign-registered entities. The larger companies get most of their revenue from abroad, and the majority of their employees work outside the country. Cross-shareholding has been abolished and there is a trend towards an Anglo-Saxon style of corporate governance. However, only around 15% of residents have invested in stock market, compared to 20% in France, and 50% in the US.

Between 2000 and 2003, early stage venture capital investments relative to GDP were 8.5% against 4% in the EU and 11.5 in the US. Later stage investments fell to the EU median. Invest in Finland and other programs attempt to attract investment. In 2000 FDI from Finland to overseas was 20 billion euro and from overseas to Finland 7 billion euro. Acquisitions and mergers have internationalized business in Finland.

Although some privatization has been gradually done, there are still several state-owned companies of importance. The government keeps them as strategic assets or because they are natural monopoly. These include e.g. Neste (oil refining and marketing), VR (rail), Finnair, VTT (research) and Posti Group (mail). Depending on the strategic importance, the government may hold either 100%, 51% or less than 50% stock. Most of these have been transformed into regular limited companies, but some are quasi-governmental (liikelaitos), with debt backed by the state, as in the case of VTT.

In 2022, the sector with the highest number of companies registered in Finland is Services with 191,796 companies followed by Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate and Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing with 159,158 and 102,452 companies respectively.

Household income and consumption

Finland's income is generated by the approximately 1.8 million private sector workers, who make an average 25.1 euro per hour (before the median 60% tax wedge) in 2007. According to a 2003 report, residents worked on average around 10 years for the same employer and around 5 different jobs over a lifetime. 62% worked for small and medium-sized enterprises. Female employment rate was high and gender segregation on career choices was higher than in the US. In 1999 part-time work rate was one of the smallest in OECD.

Future liabilities are dominated by the pension deficit. Unlike in Sweden, where pension savers can manage their investments, in Finland employers choose a pension fund for the employee. The pension funding rate is higher than in most Western European countries, but still only a portion of it is funded and pensions exclude health insurances and other unaccounted promises. Directly held public debt has been reduced to around 32% in 2007. In 2007, the average household savings rate was -3.8 and household debt 101% of annual disposable income, a typical level in Europe.

In 2008, the OECD reported that "the gap between rich and poor has widened more in Finland than in any other wealthy industrialised country over the past decade" and that "Finland is also one of the few countries where inequality of incomes has grown between the rich and the middle-class, and not only between rich and poor."

In 2006, there were 2,381,500 households of average size 2.1 people. Forty% of households consisted of single person, 32% two and 28% three or more. There were 1.2 million residential buildings in Finland and the average residential space was 38 square metres per person. The average residential property (without land) cost 1,187 euro per square metre and residential land on 8.6 euro per square metre. Consumer energy prices were 8-12 euro cent per kilowatt hour. 74% of households had a car. There were 2.5 million cars and 0.4 other vehicles. Around 92% have mobile phones and 58% Internet connection at home. The average total household consumption was 20,000 euro, out of which housing at around 5500 euro, transport at around 3000 euro, food and beverages excluding alcoholic at around 2500 euro, recreation and culture at around 2000 euro. Upper-level white-collar households (409,653) consumed an average 27,456 euro, lower-level white-collar households (394,313) 20,935 euro, and blue-collar households (471,370) 19,415 euro.

Unemployment

The unemployment rate was 10.3% in 2015. The employment rate is (persons aged 15–64) 66.8%. Unemployment security benefits for those seeking employment are at an average OECD level. The labor administration funds labour market training for unemployed job seekers, the training for unemployed job seeker can last up to 6 months, which is often vocational. The aim of the training is to improve the channels of finding employment.

Gross domestic product

Euro Membership

The American economist and The New York Times columnist Paul Krugman has suggested that the short term costs of euro membership to the Finnish economy outweigh the large gains caused by greater integration with the European economy. Krugman notes that Sweden, which has yet to join the single currency, had similar rates of growth compared to Finland for the period since the introduction of the euro.

Membership of the euro protects Finland from currency fluctuations, which is particularly important for small member states of the European Union like Finland that are highly integrated into the larger European economy. If Finland had retained its own currency, unpredictable exchange rates would prevent the country from selling its products at competitive prices on the European market. In fact, business leaders in Sweden, which is obliged to join the euro when its economy has converged with the eurozone, are almost universal in their support for joining the euro. Although Sweden's currency is not officially pegged to the euro like Denmark's currency the Swedish government maintains an unofficial peg. This exchange rate policy has in the short term benefited the Swedish economy in two ways; (1) much of Sweden's European trade is already denominated in euros and therefore bypasses any currency fluctuation and exchange rate losses, (2) it allows Sweden's non-euro-area exports to remain competitive by dampening any pressure from the financial markets to increase the value of the currency.

Maintaining this balance has allowed the Swedish government to borrow on the international financial markets at record low interest rates and allowed the Swedish central bank to quantitatively ease into a fundamentally sound economy. This has led Sweden's economy to prosper at the expense of less sound economies who have been impacted by the 2008 financial crisis. Sweden's economic performance has therefore been slightly better than Finland's since the financial crisis of 2008. Much of this disparity has, however, been due to the economic dominance of Nokia, Finland's largest company and Finland's only major multinational. Nokia supported and greatly benefited from the euro and the European single market, particularly from a common European digital mobile phone standard (GSM), but it failed to adapt when the market shifted to mobile computing.

One reason for the popularity of the euro in Finland is the memory of a 'great depression' which began in 1990, with Finland not regaining it competitiveness until approximately a decade later when Finland joined the single currency. Some American economists like Paul Krugman claim not to understand the benefits of a single currency and allege that poor economic performance is the result of membership of the single currency. These economists do not, however, advocate separate currencies for the states of the United States, many of which have quite disparate economies.

| Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Public policy

See also: Nordic modelFinnish politicians have often emulated other Nordics and the Nordic model. Nordic's have been free-trading and relatively welcoming to skilled migrants for over a century, though in Finland immigration is a relatively new phenomenon. This is due largely to Finland's less hospitable climate and the fact that the Finnish language shares roots with none of the major world languages, making it more challenging than average for most to learn. The level of protection in commodity trade has been low, except for agricultural products.

As an economic environment, Finland's judiciary is efficient and effective. Finland is highly open to investment and free trade. Finland has top levels of economic freedom in many areas, although there is a heavy tax burden and inflexible job market. Finland is ranked 16th (ninth in Europe) in the 2008 Index of Economic Freedom. Recently, Finland has topped the patents per capita statistics, and overall productivity growth has been strong in areas such as electronics. While the manufacturing sector is thriving, OECD points out that the service sector would benefit substantially from policy improvements. The IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook 2007 ranked Finland 17th most competitive, next to Germany, and lowest of the Nordics. while the World Economic Forum report has ranked Finland the most competitive country. Finland is one of the most fiscally responsible EU countries. According to the grand jury of the 2006 European Enterprise Awards, effective "entrepreneurial thinking" was held to be at the root of central Finland's position as "the most entrepreneur-friendly region in the world".

Product market

Economists attribute much growth to reforms in the product markets. According to OECD, only four EU-15 countries have less regulated product markets (UK, Ireland, Denmark and Sweden) and only one has less regulated financial markets (Denmark). Nordic countries were pioneers in liberalising energy, postal, and other markets in Europe. The legal system is clear and business bureaucracy less than most countries. For instance, starting a business takes an average of 14 days, compared to the world average of 43 days and Denmark's average of 6 days. Property rights are well protected and contractual agreements are strictly honored. Finland is rated one of the least corrupted countries in Corruption Perceptions Index. Finland is rated 13th in the Ease of Doing Business Index. It indicates exceptional ease to trade across borders (5th), enforce contracts (7th), and close a business (5th), and exceptional hardship to employ workers (127th) and pay taxes (83rd).

Job market

According to the OECD, Finland's job market is the least flexible of the Nordic countries. Finland increased job market regulation in the 1970s to provide stability to manufacturers. In contrast, during the 1990s, Denmark liberalised its job market, Sweden moved to more decentralised contracts, whereas Finnish trade unions blocked many reforms. Many professions have legally recognized industry-wide contracts that lay down common terms of employment including seniority levels, holiday entitlements, and salary levels, usually as part of a Comprehensive Income Policy Agreement. Those who favor less centralized labor market policies consider these agreements bureaucratic, inflexible, and along with tax rates, a key contributor to unemployment and distorted prices. Centralized agreements may hinder structural change as there are fewer incentives to acquire better skills, although Finland already enjoys one of the highest skill-levels in the world.

Taxation

Main article: Taxation in FinlandTax is collected mainly from municipal income tax, state income tax, state value added tax, customs fees, corporate taxes and special taxes. There are also property taxes, but municipal income tax pays most of municipal expenses. Taxation is conducted by a state agency, Verohallitus, which collects income taxes from each paycheck, and then pays the difference between tax liability and taxes paid as tax rebate or collects as tax arrears afterward. Municipal income tax is a flat tax of nominally 15-20%, with deductions applied, and directly funds the municipality (a city or rural locality). The state income tax is a progressive tax; low-income individuals do not necessarily pay any. The state transfers some of its income as state support to municipalities, particularly the poorer ones. Additionally, the state churches - Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church and Finnish Orthodox Church - are integrated to the taxation system in order to tax their members.

The middle income worker's tax wedge is 46% and effective marginal tax rates are very high. Value-added tax is 24% for most items. Capital gains tax is 30-34% and corporate tax is 20%, about the EU median. Property taxes are low, but there is a transfer tax (1.6% for apartments or 4% for individual houses) for home buyers. There are high excise taxes on alcoholic beverages, tobacco, automobiles and motorcycles, motor fuels, lotteries, sweets and insurances. For instance, McKinsey estimates that a worker has to pay around 1600 euro for another's 400 euro service - restricting service supply and demand - though some taxation is avoided in the black market and self-service culture. Another study by Karlson, Johansson & Johnsson estimates that the fraction of the buyer's income entering the service vendor's wallet (inverted tax wedge) is slightly over 15%, compared to 10% in Belgium, 25% in France, 40% in Switzerland and 50% in the United States. Tax cuts have been in every post-depression government's agenda and the overall tax burden is now around 43% of GDP compared to 51.1% in Sweden, 34.7% in Germany, 33.5% in Canada, and 30.5% in Ireland.

High income workers, for instance someone making €10000/month gross, living in the city of Vantaa and using €3000/year on commuting to work, pay 33% income tax plus 7.94% social security payments (this varies mildly depending on the age of the worker, but for someone born in 1975, it is currently in the year 2024, 7.94%). This means that 40,94% of the gross income goes to taxes and tax like payments.

State and municipal politicians have struggled to cut their consumption, which is very high at 51.7% of GDP compared to 56.6% in Sweden, 46.9% in Germany, 39.3% in Canada, and 33.5% in Ireland. Much of the taxes are spent on public sector employees, which amount to 124,000 state employees and 430,000 municipal employees. That is 113 per 1000 residents (over a quarter of workforce) compared to 74 in the US, 70 in Germany, and 42 in Japan (8% of workforce). The Economist Intelligence Unit's ranking for Finland's e-readiness is high at 13th, compared to 1st for United States, 3rd for Sweden, 5th for Denmark, and 14th for Germany. Also, early and generous retirement schemes have contributed to high pension costs. Social spending such as health or education is around OECD median. Social transfers are also around OECD median. In 2001 Finland's outsourced proportion of spending was below Sweden's and above most other Western European countries. Finland's health care is more bureaucrat-managed than in most Western European countries, though many use private insurance or cash to enjoy private clinics. Some reforms toward more equal marketplace have been made in 2007–2008. In education, child nurseries, and elderly nurseries private competition is bottom-ranking compared to Sweden and most other Western countries. Some public monopolies such Alko remain, and are sometimes challenged by the European Union. The state has a programme where the number of jobs decreases by attrition: for two retirees, only one new employee is hired.

Occupational and income structure

Finland's export-dependent economy continuously adapted to the world market; in doing so, it changed Finnish society as well. The prolonged worldwide boom, beginning in the late 1940s and lasting until the first oil crisis in 1973, was a challenge that Finland met and from which it emerged with a highly sophisticated and diversified economy, including a new occupational structure. Some sectors kept a fairly constant share of the work force. Transportation and construction, for example, each accounted for between 7 and 8% in both 1950 and 1985, and manufacturing's share rose only from 22 to 24%. However, both the commercial and the service sectors more than doubled their share of the work force, accounting, respectively, for 21 and 28% in 1985. The greatest change was the decline of the economically active population employed in agriculture and forestry, from approximately 50% in 1950 to 10% in 1985. The exodus from farms and forests provided the labour power needed for the growth of other sectors.

Studies of Finnish mobility patterns since World War II have confirmed the significance of this exodus. Sociologists have found that people with a farming background were present in other occupations to a considerably greater extent in Finland than in other West European countries. Finnish data for the early 1980s showed that 30 to 40% of those in occupations not requiring much education were the children of farmers, as were about 25% in upper-level occupations, a rate two to three times that of France and noticeably higher than that even of neighboring Sweden. Finland also differed from the other Nordic countries in that the generational transition from the rural occupations to white-collar positions was more likely to be direct, bypassing manual occupations.

The most important factor determining social mobility in Finland was education. Children who attained a higher level of education than their parents were often able to rise in the hierarchy of occupations. In the Helsinki Metropolitan Area, those who are more educated, in the long-run, will move to newer centrally located buildings. A tripling or quadrupling in any one generation of the numbers receiving schooling beyond the required minimum reflected the needs of a developing economy for skilled employees. Obtaining advanced training or education was easier for some than for others, however, and the children of white-collar employees still were more likely to become white-collar employees themselves than were the children of farmers and blue-collar workers. In addition, children of white-collar professionals were more likely than not to remain in that class.

The economic transformation also altered income structure. A noticeable shift was the reduction in wage differentials. The increased wealth produced by an advanced economy was distributed to wage earners via the system of broad income agreements that evolved in the postwar era. Organized sectors of the economy received wage hikes even greater than the economy's growth rate. As a result, blue-collar workers' income came, in time, to match more closely the pay of lower level white-collar employees, and the income of the upper middle class declined in relation to that of other groups.

The long trend of growth in living standards paired with diminishing differences between social classes was dramatically reversed during the 1990s. For the first time in the history of Finland income differences have sharply grown. This change has been mostly driven by the growth of income from capital to the wealthiest segment of the population.

See also

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: April 2023". imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "The outlook is uncertain again amid financial sector turmoil, high inflation, ongoing effects of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and three years of COVID". International Monetary Fund. 11 April 2023.

- ^ "EUROPE :: FINLAND". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Corruption Perceptions Index". Transparency International. 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 30 January 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- "Labor force, total - Finland". data.worldbank.org. World Bank & ILO. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- "Employment rate by sex, age group 20-64". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- "Unemployment by sex and age - monthly average". appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "Unemployment rate by age group". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Ulkomaankauppa".

- ^ Tilastokeskus. "Kauppa". tilastokeskus.fi. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Euro area and EU27 government deficit both at 0.6% of GDP" (PDF). ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- "Scope affirms Finland's credit ratings at AA+ with Stable Outlook". Scope Ratings. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- "Finland in Figures – National Accounts". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- "Finland - Employment by economic sector | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Kenworthy, Lane (1999). "Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–1139. doi:10.2307/3005973. JSTOR 3005973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2013.

- Moller, Stephanie; Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D.; Bradley, David; Nielsen, François (2003). "Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (1): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

- "Social Expenditure – Aggregated data". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- "Finland in Figures – Manufacturing". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- "Finland - Area, population and GDP by region | Statistic". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Finland Economy 2004, OECD

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "The Global Information Technology Report 2014 : Rewards and Risks of Big Data" (PDF). 3.weforum.org. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Finnish Economy". Embassy of Finland. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- WIPO (12 December 2023). Global Innovation Index 2023, 15th Edition. World Intellectual Property Organization. doi:10.34667/tind.46596. ISBN 9789280534320. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO (2018): The Global Innovation Index 2018: Energizing the World with Innovation. Ithaca, Fontainebleau and Geneva

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ "Statistics Finland - The growing years of Finland's industrial production". www.stat.fi. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Markus Jäntti; Juho Saari; Juhana Vartiainen (November 2005). "Growth and equity in Finland" (PDF). Siteresources.worldbank.org. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Nohlen, Dieter (2010). Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Nomos. p. 606. ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7.

- "Rahoitusmarkkinoiden liberalisointi". Taloustieto Oy. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Inflation targeting: Reflection from the Finnish experience" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "Converted". Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "Finland and the euro - European Commission". economy-finance.ec.europa.eu.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Text from PD source: US Library of Congress: A Country Study: Finland, Library of Congress Call Number DL1012 .A74 1990.

- ^ "Finnish industry: constantly adapting to a changing world – Virtual Finland". 17 January 2009. Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Geological Survey of Finland is allowing the country to reap the mining rewards". www.worldfinance.com. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- "USGS Chromium Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Sulfur Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "USGS Phosphate Production Statistics" (PDF).

- "Market shares".

- Finland in Figures. "Tilastokeskus - Labour Market". Tilastokeskus.fi. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Biotechnology: A Promising High Tech Sector in Finland Spotlight on Finland Nature.com

- "Monien mahdollisuuksien teknologia" (PDF). Tekes.fi. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "The PPI Top 100". Risiinfo.com. 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Finland 1917-2007 (30 March 2007). "Statistics Finland - Changes in the use and sources of energy". Stat.fi. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Finland – Energy Mix Fact Sheet" (PDF). January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Nuclear power in Finland, fetched 26 November 2010

- "Uraanikaivokset". Gtk.fi. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "The largest companies (turnover)". Largestcompanies.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- "Iittala Group". Linkedin.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- "Quick History: Marimekko". Apartmenttherapy.com. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- "Artek". Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom". Heritage.org. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Puttonen, Vesa (26 March 2009). "Onko omistamisella väliä?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Foreign Ownership on Foreign Stock Exchanges". 19 December 2008. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Andersen, Torben M.; Holmström, Bengt; Honkopohja, Seppo; Korkman, Sixten; Söderström, Hans Tson; Vartiainen, Juhana (4 December 2007). "The Nordic Model, Embracing Globalization and Sharing Risks" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Invest in Finland". Investinfinland.fi. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "State majority-owned companies". Vnk.fi. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Industry Breakdown of Companies in Finland". HitHorizons.

- "Tilastokeskus - Tehdyn työtunnin hinta 23-27 euroa". Stat.fi. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Sivua ei löytynyt". Etk.fi. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Tilastokeskus - Pienten ja keskisuurten yritysten merkitys työllistäjinä on kasvanut" (in Finnish). Tilastokeskus.fi. 14 February 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ The Nordic Model of Welfare: A Historical Reappraisal, by Niels Finn Christiansen

- Lassila, Jukka; Määttänen, Niku; Valkonen, Tarmo (29 March 2007). "Ikääntymisen taloudelliset vaikutukset ja niihin varautuminen" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "CIA Factbook: Public Debt". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "Taloussanomat". Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- "Helsingin Sanomat - International Edition - Business & Finance". 6 July 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Sähkön hinta kuluttajatyypeittäin 1994-, c/kWh". Stat.fi. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "Statistics Finland: Transport and Tourism". Tilastokeskus.fi. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- "Own-account worker households' consumption has grown most in 2001-2006". Tilastokeskus.fi. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Viinikka, Joanna. "Statistics Finland - Labour Force Survey". tilastokeskus.fi. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Unemployment rate 10.3 per cent in March". Statistics Finland. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Annoying Euro Apologetics P. Krugman, The Conscience of a Liberal, The New York Times, 22 July 2015

- Bradshaw, Julia (27 August 2015). "Sweden's monetary drama could turn noir". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "The Finnish Disease". Krugman.blogs.nytimes.com. June 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Kilpailuvalvonta, kilpailun edistäminen ja hankintojen valvonta". Kilpailu- ja kuluttajavirasto.

- "World Competitiveness Rankings - IMD". IMD business school. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- "Global Competitiveness Report". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 25 January 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- European Commission, The Winners of the 2006 European Enterprise Awards, MEMO/06/465 published on 8 December 2006, accessed on 14 July 2024

- "Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom". Heritage.org. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Ranking of economies - Doing Business - World Bank Group". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Yrityskohtaiset palkkaratkaisut – Yritysten kokemuksia ja vihjeitä toteutukseen" (PDF) (in Finnish). Elinkeinoelämän keskusliitto. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013.

- ^ Verohallitus. Taxation of resident individuals: Gross income. "Finnish Tax Administration". Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "Countries Compared by Economy > Tax > Total tax wedge > Single worker. International Statistics at NationMaster.com". Nationmaster.com. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Economic Survey of Finland in 2004, OECD

- McKinsey: Finland's Economy Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Karlson, Johansson & Johnsson (2004), p. 184.

- Tilastokeskus. "Government Finance". Tilastokeskus.fi.

- "Veroprosenttilaskuri". Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Is Japan's bureaucracy still living in the 17th century? | The Japan Times Online Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Yritysverotus kilpailukykyinen – seuraavaksi palkkavero pohjoismaiselle tasolle - Elinkeinoelämän keskusliitto". Ek.fi. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Bratu, Cristina; Harjunen, Oskari; Saarimaa, Tuukka (2021). "City-wide effects of new housing supply: Evidence from moving chains". VATT Institute for Economic Research Working Papers 146. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3929243. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 237930542.

- Pajunen, A.: Tuloerot Suomessa vuosina 1966-2003, Statistics Finland, 2006.

External links

- Current statistics from Statistics Finland

- Economic indicators from Findicator

- Tariffs applied by Finland as provided by ITC's Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements.

- Finland Exports, Imports and Trade Balance

| Finland articles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||

| Geography | |||||

| Politics | |||||

| Economy | |||||

| Society |

| ||||

| Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Guidelines | |

| Economy of Europe | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other entities | |

| Other entities | |