| |

| Continent | Eurasia |

|---|---|

| Region | Eastern Mediterranean |

| Coordinates | 33°50′N 35°50′E / 33.833°N 35.833°E / 33.833; 35.833 |

| Area | Ranked 161st |

| • Total | 10,452 km (4,036 sq mi) |

| • Land | 98.37% |

| • Water | 1.63% |

| Coastline | 225 km (140 mi) |

| Highest point | Qurnat as Sawda' 3,088 m (10,131 ft) |

| Lowest point | Mediterranean Sea 0 m (0 ft) |

| Longest river | Litani River 140 km (87 mi) |

| Largest lake | Lake Qaraoun 1,600 km (620 sq mi) |

| Climate | Mediterranean |

| Natural resources | Limestone, iron ore, salt, water-surplus state in a water-deficit region, arable land |

| Natural hazards | dust storms |

| Environmental issues | deforestation, soil erosion, desertification, air pollution |

| Exclusive economic zone | 19,516 km (7,535 sq mi) |

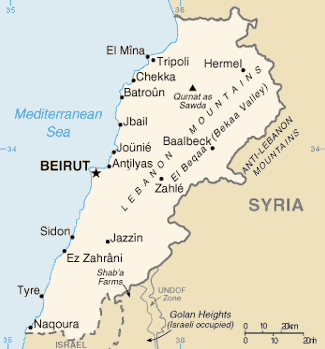

Lebanon is a small country in the Levant region of the Eastern Mediterranean, located at approximately 34˚N, 35˚E. It stretches along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea and its length is almost three times its width. From north to south, the width of its terrain becomes narrower. Lebanon's mountainous terrain, proximity to the sea, and strategic location at a crossroads of the world were decisive factors in shaping its history.

The country's role in the region, as indeed in the world at large, was shaped by trade. It serves as a link between the Mediterranean world and India and East Asia. The merchants of the region exported oil, grain, textiles, metal work, and pottery through the port cities to Western markets.

Physical geography and regions

The area of Lebanon is 10,452 square kilometres (4,036 sq mi). The country is roughly rectangular in shape, becoming narrower toward the south and the farthest north. Its widest point is 88 kilometres (55 mi), and its narrowest is 32 kilometres (20 mi); the average width is about 56 kilometres (35 mi). Because Lebanon straddles the northwest of the Arabian Plate, it is sometimes geopolitically grouped together with nations with adjacent tectonic proximations such as Syria, Yemen, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the Egyptian Sinai, Palestine, Israel and the UAE.

The physical geography of Lebanon is influenced by natural systems that extend outside the country. Thus, the Beqaa Valley is part of the Great Rift system, which stretches from southern Turkey to Mozambique in Africa. Like any mountainous country, Lebanon's physical geography is complex. Land forms, climate, soils, and vegetation differ markedly within short distances. There are also sharp changes in other elements of the environment, from good to poor soils, as one moves through the Lebanese mountains.

A major feature of Lebanese topography is the alternation of lowland and highland that runs generally parallel with a north-to-south orientation. There are four such longitudinal strips between the Mediterranean Sea and Syria: the coastal strip (or the maritime plain), western Lebanon, the central plateau, and eastern Lebanon.

The extremely narrow coastal strip stretches along the shore of the eastern Mediterranean. Hemmed in between sea and mountain, the sahil, as it is called in Lebanon, is widest in the north near Tripoli, where it is only 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) wide. A few kilometers south at Juniyah the approximately 1.5-kilometer-wide plain is succeeded by foothills that rise steeply to 750 metres (2,460 ft) within 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) from the sea. For the most part, the coast is abrupt and rocky. The shoreline is regular with no deep estuary, gulf, or natural harbor. The maritime plain is especially productive of fruits and vegetables.

The western range, the second major region, is the Lebanon Mountains, sometimes called Mount Lebanon, or Lebanon proper before 1920. Since Roman days the term Mount Lebanon has encompassed this area. Antilibanos (Anti-Lebanon) was used to designate the eastern range. Geologists believe that the twin mountains once formed one range. The Lebanon Mountains are the highest, most rugged, and most imposing of the whole maritime range of mountains and plateaus that start with the Nur Mountains in northern Syria and end with the towering massif of Sinai. The mountain structure forms the first barrier to communication between the Mediterranean and Lebanon's eastern hinterland. The mountain range is a clearly defined unit having natural boundaries on all four sides. On the north it is separated from the Al-Ansariyah mountains of Syria by Nahr al-Kabir ("the great river"); on the south it is bounded by Al Qasimiyah River, giving it a length of 169 kilometers. Its width varies from about 56.5 kilometres (35.1 mi) near Tripoli to 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi) on the southern end. It rises to alpine heights southeast of Tripoli. Qurnat as Sawda' ("the black nook") reaches 3,360 metres (11,020 ft) and is the highest mountain of Lebanon. Of the other peaks that rise east of Beirut, Mount Sannine (2,695 metres (8,842 ft)) is the highest. Ahl al Jabal ("people of the mountain"), or simply jabaliyyun, has referred traditionally to the inhabitants of western Lebanon. Near its southern end, the Lebanon Mountains branch off to the west to form the Shuf Mountains.

The third geographical region is the Beqaa Valley. This central highland between the Lebanon Mountains and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains is about 177 kilometres (110 mi) in length and 9.6 to 16 kilometers wide and has an average elevation of 762 metres (2,500 ft). Its middle section spreads out more than its two extremities. Geologically, the Beqaa is the medial part of a depression that extends north to the western bend of the Orontes River in Syria and south to Jordan through Arabah to Aqaba, the eastern arm of the Red Sea. The Beqaa is the country's chief agricultural area and served as a granary of Roman Syria. Beqaa is the Arabic plural of buqaah, meaning a place with stagnant water.

Emerging from a base south of Homs in Syria, the eastern mountain range, or Anti-Lebanon (Lubnan ash Sharqi), is almost equal in length and height to the Lebanon Mountains. This fourth geographical region falls swiftly from Mount Hermon to the Hawran Plateau, whence it continues through Jordan south to the Dead Sea. The Barada Gorge divides Anti-Lebanon. In the northern section, few villages are on the western slopes, but in the southern section, featuring Mount Hermon (2860 meters), the western slopes have many villages. Anti-Lebanon is more arid, especially in its northern parts, than Mount Lebanon and is consequently less productive and more thinly populated.

-

Jayroun

Jayroun

-

White mule in the Dunnieh Mountains

White mule in the Dunnieh Mountains

-

Jabal Moussa Biosphere Rerserve

Jabal Moussa Biosphere Rerserve

-

Kadisha valley

Kadisha valley

-

Lebanese coastline

Lebanese coastline

-

Mount Lebanon

-

Mount Sannine

Mount Sannine

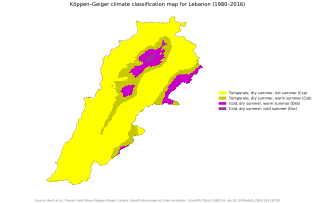

Climate

See also: Climate change in the Middle East and North Africa

Lebanon has a Mediterranean climate characterized by a long, hot, and dry summer, and a cool, rainy winter. Fall is a transitional season with a lowering of temperature and little rain; spring occurs when the winter rains cause the vegetation to revive. Topographical variation creates local modifications of the basic climatic pattern. Along the coast, summers are warm and humid, with little or no rain. Heavy dews form, which are beneficial to agriculture. The daily range of temperature is not wide. A west wind provides relief during the afternoon and evening; at night the wind direction is reversed, blowing from the land out to sea.

Winter is the rainy season, with major precipitation falling after December. Rainfall is generous but is concentrated during only a few days of the rainy season, falling in heavy cloudbursts. The amount of rainfall varies greatly from one year to another. A hot wind blowing from the Egyptian desert called the khamsin (Arabic for "fifty"), may provide a warming trend during the fall but more often occurs during the spring. Bitterly cold winds may come from Southern Europe. Along the coast the proximity to the sea provides a moderating influence on the climate, making the range of temperatures narrower than it is inland, but the temperatures are cooler in the northern parts of the coast where there is also more rain.

In the Lebanon Mountains the gradual increase in altitudes produces extremely cold winters with more precipitation and snow. The summers have a wider daily range of temperatures and less humidity. In the winter, frosts are frequent and snows heavy; in fact, snow covers the highest peaks for much of the year. In the summer, temperatures may rise as high during the daytime as they do along the coast, but they fall far lower at night. Inhabitants of the coastal cities, as well as visitors, seek refuge from the oppressive humidity of the coast by spending much of the summer in the mountains, where numerous summer resorts are located. The influence of the Mediterranean Sea is abated by the altitude and, although the precipitation is even higher than it is along the coast, the range of temperatures is wider and the winters are more severe.

The Beqaa Valley and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains are shielded from the influence of the sea by the Lebanon Mountains. The result is considerably less precipitation and humidity and a wider variation in daily and yearly temperatures. The khamsin does not occur in the Beqaa Valley, but the north winter wind is so severe that the inhabitants say it can "break nails". Despite the relatively low altitude of the Beqaa Valley (the highest point of which, near Baalbek, is only 1,100 meters or 3,609 feet) more snow falls there than at comparable altitudes west of the Lebanon Mountains.

Because of their altitudes, the Anti-Lebanon Mountains receive more precipitation than the Beqaa Valley, despite their remoteness from maritime influences. Much of this precipitation appears as snow, and the peaks of the Anti-Lebanon, like those of the Lebanon Mountains, are snow-covered for much of the year. Temperatures are cooler than in the Beqaa Valley.

The Beqaa Valley is watered by two rivers that rise in the watershed near Baalbek: the Orontes flowing north (in Arabic it is called Nahr al-Asi, "the Rebel River", because this direction is unusual), and the Litani flowing south into the hill region of the southern Biqa Valley, where it makes an abrupt turn to the west in southern Lebanon. The river’s lower course is known as Qāsimiyyah. The Orontes continues to flow north into Syria and eventually reaches the Mediterranean in Turkey. Its waters, for much of its course, flow through a channel considerably lower than the surface of the ground. The Nahr Barada, which waters Damascus, has as its source a spring in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains.

Smaller springs and streams serve as tributaries to the principal rivers. Because the rivers and streams have such steep gradients and are so fast moving, they are erosive instead of depository in nature. This process is aided by the soft character of the limestone that composes much of the mountains, the steep slopes of the mountains, and the heavy rainstorms. The only permanent lake is Lake Qaraoun, about ten kilometers east of Jezzine. There is one seasonal lake, fed by springs, on the eastern slopes of the Lebanon Mountains near Yammunah, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) southeast of Tripoli.

Temperatures are rising in Lebanon as a part of global warming. Lebanon is considered to be part of the Fertile Crescent, yet in the meantime with the severe climate changes, it might lose fertility.

-

Snow-covered karstic formations in the Danniyeh mountains.

Snow-covered karstic formations in the Danniyeh mountains.

-

Lebanon from space. Snow cover can be seen on the western and eastern mountain ranges.

Lebanon from space. Snow cover can be seen on the western and eastern mountain ranges.

-

Snow in Lebanon's two mountain ranges, Jebel Liban and Jabal ash Sharqi in March 2011.

Snow in Lebanon's two mountain ranges, Jebel Liban and Jabal ash Sharqi in March 2011.

| Climate data for Beirut International Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

39.3 (102.7) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.8 (85.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

0.2 (32.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 154 (6.1) |

127 (5.0) |

84 (3.3) |

31 (1.2) |

11 (0.4) |

1 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0 (0) |

5 (0.2) |

60 (2.4) |

115 (4.5) |

141 (5.6) |

730 (28.7) |

| Average rainy days | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 62 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64 | 64 | 64 | 66 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 65 | 62 | 60 | 63 | 66 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 7 (45) |

8 (46) |

9 (48) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

19 (66) |

16 (61) |

11 (52) |

8 (46) |

14 (57) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 131 | 143 | 191 | 243 | 310 | 348 | 360 | 334 | 288 | 245 | 200 | 147 | 2,940 |

| Source 1: Pogodaiklimat.ru | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun 1931–1960)

Source 3: Time and Date (dewpoints, between 1985–2015) | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) | 17.5 °C (63.5 °F) | 17.5 °C (63.5 °F) | 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) | 21.3 °C (70.3 °F) | 24.9 °C (76.8 °F) | 27.5 °C (81.5 °F) | 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) | 28.1 °C (82.6 °F) | 26.0 °C (78.8 °F) | 22.6 °C (72.7 °F) | 20.1 °C (68.2 °F) |

Area and boundaries

Area

Total: 10,452 km (4,036 sq mi)

Land: 10,282 km (3,970 sq mi)

Water: 170 km (66 sq mi)

Land boundaries:

Total: 454 km (282 mi)

Border countries:Israel 79 km (49.1 mi), Syria 375 km (233 mi)

Coastline: 225 km (140 mi)

Maritime claims:

Territorial sea: 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi)

Exclusive Economic Zone: 19,516 km (7,535 sq mi)

Elevation extremes:

Lowest point: Mediterranean Sea 0 m (0 ft) (sea level)

Highest point: Qurnat as Sawda' 3,088 m (10,131 ft)

Resources and land use

Limestone, iron ore, salt, water-surplus state in a water-deficit region, arable land

Land use:

arable land: 10.72%

permanent crops: 12.06%

other: 77.22% (2011)

Irrigated land: 1,040 km (401.55 sq mi) (2011)

Total renewable water resources: 4.5 km (1.1 cu mi) (2011)

Water in Lebanon

Water is becoming a scarce resource in Lebanon due to climate change, which leads to different rainfall patterns as well as to inefficient methods of distribution within the country. Most of Lebanon's rainfall is in the four months of winter, but over the last 45 years, the Ministry of Environment (Lebanon) estimates that rainfall has decreased overall between 5 and 20 percent. The coastal strip of Lebanon gets approximately 2,000 mm of rain per year, while the Beqaa Valley to the east gets only one-tenth as much. In 2004, only about 21% of households across Lebanon had constant access to water in the summer months, with most of those households concentrated in or near Beirut. It is predicted that in future years, there will be higher temperatures, lower rainfall, and longer droughts, leading to even less access to water. According to the Ministry of Environment, several factors that are putting stress on Lebanon's water resources are unsustainable water management practices, increasing water demand from all sectors, water pollution, and ineffective water governance. Lebanon has struggled with inadequate water and sanitation services for many years. The factors with the greatest effect on quality and quantity of water resources in Lebanon are population growth, urbanization (88% of the population now lives in urban areas), economic growth, and climate change. In recent years, population growth has been increased rapidly with the addition of many Syrian refugees. Some new projects have been proposed to restructure the water sector. Currently, over 48 percent of water supplied by the public system is lost through seepage and wastewater networks are extremely poor, or even non-existent in some areas. One project that is currently being implemented by the Ministry of Environment in collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) focusses on harvesting rainwater from agricultural greenhouse tops in order to increase water harvesting and reduce the pressure on pumping groundwater. This project is expected to increase water availability during the especially critical months of late summer and early autumn when there is less precipitation, which would help to reduce the risk of salinity in both soil and water, and to increase the resilience of crops faced with prolonged drought. There are also proposed projects that suggest the agricultural sector use recycled waste water to allow for more fresh and potable water for consumption. This would be a huge improvement, as solid-wast treatment facilities are in short supply, and over 92 percent of Lebanon's sewage runs untreated directly into water-courses and the sea. If Lebanon does not reform its water sector, it is likely that there will be chronic and critical water shortages by 2020, which would create needs the Ministry of Energy and Water (MEW) would be unable to meet. Water is becoming a scarce resource and if Lebanon instates reformed practices, the progression forward into future water scarcity can be slowed.

Environmental concerns

Natural hazards include dust storms.

Current environmental degradation concerns include deforestation, soil erosion, desertification, air pollution in Beirut from vehicular traffic and the burning of industrial wastes, and pollution of coastal waters from raw sewage and oil spills.

Lebanon's rugged terrain historically helped isolate, protect, and develop numerous factional groups based on religion, clan, and ethnicity.

Air quality in Lebanon

As a result of increasingly hot summers and its location within the Mediterranean region, which is often cited for having long episodes of pollution, Lebanon, Beirut in particular, is at high risk for air pollution. Approximately 93 percent of Beirut's population is exposed to high levels of air pollution, which can most often be attributed to vehicle-induced emissions, whether it be long-range travel or short commuting traffic. The cost of air pollution to health may exceed ten million dollars a year. The levels of air pollution in Beirut are increasing annually, and were already above acceptable WHO (World Health Organization) standards by 2011. The most noted pollution in Beirut is particulate matter (street dust), chemicals in the air, and vehicle exhaust. Air pollution is exacerbated by city structure and inadequate urban management as indicated by high buildings on narrow streets, which contain air pollutants. Some recommendations for improvement of air quality include encouragement of carpooling and citywide biking, alternative fuels for vehicles, and a widened public transit sector.

The question of air quality has received considerable attention and funding by Lebanon's foreign partners. Between 2013 and 2017, the Lebanese ministry of environment was granted a donation of over 10 million Euros by Greece and the European Union to establish a national air monitoring network, which included at its peak 25 stations. This network was launched in October 2017 at a major event bringing together 26 different institutions; it was to serve as the cornerstone of Lebanon's National Strategy for Air Quality Management, which was released at the end of the same year. By mid-2019, however, the ministry of environment ceased to maintain and operate this network, involving budgetary restrictions. Stations were subsequently looted, even in central Beirut.

Land pollution in Lebanon

Sukleen, Lebanon's largest waste disposal company has a waste management process that goes through several stages, including clean-up and collection, sorting and composting, and burial. However, many argue that Lebanon needs a much better system for disposal of waste to reduce pollution and environmental degradation. The Litani River is Lebanon's largest river and many farms use the river's water to irrigate land and crops. Because of Lebanon's poor waste management system, a lot of waste and pollution ends up in the Litani and contaminates the crops, in turn endangering the health of consumers and farmers alike, contributing to environmental degradation, as well as hurting the agricultural reputation and economy.

Trash protests of January 2014

In January 2014, protests in the town of Naameh began to arise, effectively blocking disposal of garbage at the landfill for three days. The protests were instated in response to the continued use of the landfill in Naameh beyond the date it was originally meant to close. The landfill began as a six-year project in 1997, but has remained open for seventeen years as of 2015, and without a sufficient alternative location for garbage disposal, it is likely that it will remain open for the foreseeable future. In 1997, Naameh became the country's primary landfill and was initially supposed to hold two million tons of waste. The landfill currently holds ten million tons of trash, and is still in use. Residents of the area in 2014 did not want to extend the landfill agreement, and staged the protests to prevent future plans.

The company in charge of the majority of the area's collection and cleanup of trash is called Sukleen. It serves 364 towns and municipalities within Beirut and Mount Lebanon. The total waste collected by the company rose from 1,140 tons daily in 1994, to 3,100 tons in 2014. Sukleen is the largest government-contracted private waste management company in Lebanon. In response to the protests, which were asking the government for more efficient waste management systems along with the closure of the landfill in Naameh, Sukleen responded to environmentalists by halting service to Beirut and Mount Lebanon for three days. Because the Naameh landfills were closed and Sukleen was out of service, trash began to pile up in the streets of the city, affecting everyone citywide and drawing attention to the issue of city/region waste-management issues.

See also

References

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: AbuKhalil, As'ad (1989). "Geography". In Collelo, Thomas (ed.). Lebanon: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 42–48. OCLC 44356055.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: AbuKhalil, As'ad (1989). "Geography". In Collelo, Thomas (ed.). Lebanon: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 42–48. OCLC 44356055.

- Egyptian Journal of Geology – Volume 42, Issue 1 – Page 263, 1998

- "Litani River | Lebanon, Middle East, Map, & UN Resolution | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-12-01. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- Taher, Hanadi (23 July 2019). "Climate Change and Economic Growth in Lebanon". International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy. 9 (5): 20–24. doi:10.32479/ijeep.7806. S2CID 200071211. ProQuest 2288759604.

- Göll, Edgar (2017-07-12). "Future Challenges of Climate Change in the MENA Region". IAI Istituto Affari Internazionali (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- "Climate of Beirut" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Libanon – Beyrouth" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- "Climate & Weather Averages at Beirut Airport weather station (40100)". Time and Date. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Monthly Beirut water temperature chart". seatemperature.org. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ Salti, Nisreen; Chaaban, Jad (November 2010). "The role of sectarianism in the allocation of public expenditure in postwar Lebanon". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 42 (4): 637–655. doi:10.1017/S0020743810000851. JSTOR 41308713. S2CID 163433882.

- ^ Brooks, David B. (2007). "Fresh Water in the Middle East and North Africa". Integrated Water Resources Management and Security in the Middle East. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series. pp. 33–64. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5986-5_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-5984-1.

- "Republic of Lebanon, Ministry of Environment. "Water Sector" 2012". Archived from the original on 2016-12-19. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ^ UNHCR. Refugees from Syria: Lebanon. UNHCR, March 2015. Print.

- ^ "Climate Change Lebanon. "Water." Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Environment. 2014". Archived from the original on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- "UNDP: Lebanon. "Lebanese Centre for Water Conservation and Management (LCWCM)." UNDP, 2012". Archived from the original on 2018-07-15. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ^ Saliba, N. A.; Moussa, S.; Salame, H.; El-Fadel, M. (June 2006). "Variation of selected air quality indicators over the city of Beirut, Lebanon: Assessment of emission sources". Atmospheric Environment. 40 (18): 3263–3268. Bibcode:2006AtmEn..40.3263S. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.01.054.

- ^ "Al-Azar, Maha. "AUB Air Pollution Study: Almost All Beirutis Exposed to High Levels of Air Pollution." American University of Beirut. N.p., 7 May 2011. Web". Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Lebanon's air pollution nears alarming level - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- "EU supports Lebanon in its quest for a cleaner air | EU Neighbours". www.euneighbours.eu. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- "Lebanon's National Air Quality Management Strategy 2015-2030" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Alkantar, Bassam. "Lebanon: Garbage Drowns 364 Towns Amid Landfill Dispute." Al Akhbar- English. 20 Jan. 2014. Web". Archived from the original on 2014-07-24. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ^ "Hamieh, Rameh. "Lebanon's Litani Pollution Levels Threaten Agricultural Sector." Al Akhbar English. N.p., 19 Dec. 2011. Web". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ^ "Lebanon's Garbage Standoff." The Stream. Al Jazeera, 20 Jan. 2014. Web. http://stream.aljazeera.com/story/201401202105-0023403 Archived 2015-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Waste Can't Be Managed without Landfills: Lebanon Environment Minister". The Daily Star. Lebanon. 5 January 2015.

| Lebanon articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||

| Geography | |||

| Politics | |||

| Economy | |||

| Culture | |||