Shlomo Molla, Abatte Barihun, Hagit Yaso Shlomo Molla, Abatte Barihun, Hagit Yaso | ||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1.75% of the Israeli population | ||||||

| 4,000 | ||||||

| 1,000 | ||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Judaism (Haymanot · Rabbinism) | ||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||

| African Jews · other Jewish groups Amhara · Tigrinya · Agaw · other Habeshas | ||||||

Beta Israel (Ge'ez: ቤተ እስራኤል—Bēta 'Isrā'ēl, modern Bēte 'Isrā'ēl; EAE: "Betä Ǝsraʾel"; Hebrew: בֵּיתֶא יִשְׂרָאֵל - Beyte (beyt) Israel, "Community of Israel" also known as Ethiopian Jews (Hebrew: יְהוּדֵי אֶתְיוֹפְּיָה: Yhudey Etiopiya, Ge'ez: "የኢትዮጵያ አይሁድዊ", ye-Ityoppya Ayhudi), are the names of Jewish communities which lived in the area of Aksumite and Ethiopian Empires (Habesh or Abyssinia), nowadays divided between Amhara and Tigray Regions.

Beta Israel lived in North and North-Western Ethiopia, in more than 500 small villages spread over a wide territory, among Muslim and predominantly Christian ruling populations. Most of them were concentrated in the area around Lake Tana and north of it, in the Tigray among the Wolqayit, Shire and Tselemti and Amhara Region of Gonder regions, among the Semien, Dembia, Segelt, Quara, Belesa, and small numbers lived in the city of Gonder.

— Hagar Salamon

It was decided that the Israeli Law of Return applied to the Beta Israel in March 14, 1977 after a Halakhic and constitutional discussions. The Israeli and American governments have mounted aliyah operations, most notably during Operation Brothers in Sudan between 1979-1990 (which includes the major operations Moses and Joshua) and in the 1990s from Addis Ababa (which includes Operation Solomon).

The related Falash Mura are the descendants of Beta Israel who converted to Christianity. Some are returning to the practices of Judaism, living in communities and returning to Judaism. Beta Israel spiritual leaders, including Liqa Kahnet Raphael Hadane have argued for the acceptance of the Falash Mura as Jews. The Israeli government applied on the Falash Mura the resolution 2948 in February 16, 2003 which gives those who are descendants from Jewish mothers lineage the right to emigrate to Israel under the Entry Law and to obtain citizenship only if they converted to Orthodox Judaism. This resolution is a matter of controversy within Israeli society.

Today, there are 81,000 Ethiopian Israelis who were born in Ethiopia, while 38,500 or 32% of the community are native born Israelis.

Terminology

Throughout its history the community has been called a large number of names. According to tradition the name "Beta Israel" originated in the 4th century when the community refused to convert to Christianity during the rule of Abreha and Atsbeha (identified with Se'azana and Ezana), the monarchs of the Aksumite Empire who embraced Christianity. This name stands opposite to "Beta Christian" (Christianity) and wasn't originally attributed any negative meanings and the community has used it ever since as its official name. Since the 1980s it has also become the official name used in the scientific literature to describe the community. The term Esra'elawi (Israelites) which is related to the name Beta Israel that is used by the community to refer to its members.

The name Ayhud (Jews) is rarely used in the community since the Christians used it as a derogatory term. Only with the strengthening ties with other Jewish communities in the 20th century did the name begin to be commonly used by the community itself. The term 'Ivrawi (Hebrews) was used to refer to the Chawa (free man) in the community, which were opposed to Barya (slave). The term Oritawi (Torah-true) was used to refer to the community members and since the 19th Century it has become opposite to the term Falash Mura (Converts).

The major derogatory term Falasha (foreigners/exiles) was given to the community by the Emperor Yeshaq in the 15th century. Another term Agaw which refers to the Agaw people, the original inhabitants of northwest Ethiopia, is considered derogatory since it incorrectly associates the community with the pagan Agaw. Other derogatory terms by which the community has been known include Attenkun (don't touch us) named after the strict purity laws of the community, Kayla (one of the Agaw languages spoken by them) meaning in dispute, Christ killers, Tebiban (possessor of secret knowledge), Buda (evil eye), Jib (Hyenas) and Jiratam (tail), Serategna (worker), Balla Ejj (craftsmen), Gdmoch (the people of the field). There were also local terms Fogera in Wolqayt and Tsegede, Kaylasha (combination of Kayla and Falasha) in Armachiho, Mito in Gojjam, Damot and Gibe, Damenenza (his blood will be upon them) in Gojjam and Shifalasha in Lasta. In other languages Fndz'a in Oromo and Nafura (Blacksmiths) in Gurage.

Geography

Origins

Oral traditions

There is no independent tradition of origin transmitted over the ages among the Ethiopian Jews. The known Beta Israel versions of the Ethiopian legend of origin take as their basis the account of Menelik's return to Ethiopia. Though all the available traditions correspond to recent interpretations, they certainly reflect ancient convictions. According to Jon Abbink, three different versions are to be distinguished among the traditions which were recorded from the priests of the community.

By versions of this type the Beta Israel expressed their wish to be regarded not necessarily as descendants of king Solomon, but as contemporaries of Solomon and Menelik, originating from the kingdom of Israel.

According to these versions, the forefathers of the Beta Israel are supposed to have arrived in Ethiopia coming from the North, independently from Menelik and his company:

The Falashas [sic] migrated like many of the other sons of Israel to exile in Egypt after the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians in 586 the time of the Babylonian exile. This group of people was led by the great priest On. They remained in exile in Egypt for few hundred years until the reign of Cleopatra. When she was engaged in war against Augustus Caesar the Jews supported her. When she was defeated, it became dangerous for the small minorities to remain in Egypt and so there was another migration (approximately between 39-31 BCE). Some of the migrants went to South Arabia and further to the Yemen. Some of them went to the Sudan and continued on their way to Ethiopia, helped Egyptian traders who guided them through the desert. Some of them entered Ethiopia through Quara (near the Sudanese border), and some came via Eritrea. ...Later in time, there was an Abyssinian king named Kaleb, who wished to enlarge his kingdom, so he declared war on the Yemen and conquered it. And so, during his reign there came another group of Jews to Ethiopia, led by Azonos and Phinhas.

Kebra Nagast

The Ethiopian history described in the Kebra Negast, or "Book of the Glory of Kings," relates that Ethiopians are descendants of Israelite tribes who came to Ethiopia with Menelik I, alleged to be the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (or Makeda, in the legend) (see 1 Kings 10:1–13 and 2 Chronicles 9:1–12). The legend relates that Menelik, as an adult, returned to his father in Jerusalem, and then resettled in Ethiopia, and that he took with him the Ark of the Covenant.

Eldad ha-Dani

To prove the antiquity and authenticity of their own claims, the Beta Israel cite the 9th-century testimony of Eldad ha-Dani (the Danite), from a time before even the Zagwean dynasty was established. Eldad was a Jewish man who suddenly turned up in Egypt and created a great stir in the Egyptian Jewish community (and elsewhere in the Mediterranean Jewish communities he travelled to) with claims that he had come from a Jewish kingdom of pastoralists far to the south. The only language he spoke was a hitherto unknown dialect of Hebrew. Although he strictly followed the Mosaic commandments his observance differed in some details from Rabbinic halakhah, so that some thought he might be a Karaite, even if his practice differed from theirs too. He carried Hebrew books with him that supported his explanations of halakhah, and he was able to cite ancient authorities in the sagely traditions of his own people. He said that the Jews of his own kingdom derived from the tribe of Dan, which had fled the civil war in the Kingdom of Israel between Solomon's son Rehoboam and Jeroboam the son of Nebat, by resettling in Egypt. From there they moved southwards up the Nile into Ethiopia, and the Beta Israel say this confirms that they are descended from these Danites. Some Beta Israel, however, assert even nowadays that their Danite origins go back to the time of Moses himself, when some Danites parted from other Jews right after the Exodus and moved south to Ethiopia. Eldad the Danite does indeed speak of at least three waves of Jewish immigration into his region, creating other Jewish tribes and kingdoms, including the earliest wave that settled in a remote kingdom of the "tribe of Moses": this was the strongest and most secure Jewish kingdom of all, with farming villages, cities and great wealth.

Other sources tell of many Jews who were brought as prisoners of war from ancient Israel by Ptolemy I and also settled on the border of his kingdom with Nubia (Sudan). Another tradition handed down in the community from father to son asserts that they arrived either via the old district of Qwara in northwestern Ethiopia, or via the Atbara River, where the Nile tributaries flow into Sudan. Some accounts even specify the route taken by their forefathers on their way upstream from Egypt.

Scholarly views

Early secular scholars saw the Beta Israel to be the direct descendant of Jews who lived in ancient Ethiopia, whether they were the descendants of an Israelite tribe, or converted by Jews living in Yemen, or by the Jewish community in southern Egypt at Elephantine. In 1829, Marcus Louis wrote that the ancestors of the Beta Israel related to the Asmach which also called Sembritae ("foreigners") an Egyptian regiment numbering 240,000 soldiers and mentioned by Greek geographers and historians. The Asmach emigrated or exiled from Elephantine to Kush in the time of Psamtik I or Psamtik II and settled in Sennar and Abyssinia. It is possible that Shebna party from Rabbinic accounts was part of the Asmach.

In the 1930s Jones and Monro argued that the chief Semitic languages of Ethiopia may suggest an antiquity of Judaism in Ethiopia. "There still remains the curious circumstance that a number of Abyssinian words connected with religion, such as the words for Hell, idol, Easter, purification, and alms– are of Hebrew origin. These words must have been derived directly from a Jewish source, for the Abyssinian Church knows the scriptures only in a Ge'ez version made from the Septuagint."

Richard Pankhurst summarized the various theories offered about their origins as of 1950 that the first members of this community were

(1) converted Agaws, (2) Jewish immigrants who intermarried with Agaws, (3) immigrant Yemeni Arabs who had converted to Judaism, (4) immigrant Yemeni Jews, (5) Jews from Egypt, and (6) successive waves of Yemeni Jews. Traditional Ethiopian savants, on the one hand, have declared that 'We were Jews before we were Christians', while more recent, well-documented, Ethiopian hypotheses, notably by two Ethiopian scholars, Dr Taddesse Tamrat and Dr Getachew Haile... put much greater emphasis on the manner in which Christians over the years converted to the Falasha faith, thus showing that the Falashas were culturally an Ethiopian sect, made up of ethnic Ethiopians.

According to Jacqueline Pirenne, numerous Sabaeans left north Arabia and crossed over the Red Sea to Ethiopia to escape from the Assyrians, who had devastated the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the 8th and 7th centuries BC. She further states that a second major wave of Sabeans crossed over to Ethiopia in the 6th and 5th centuries BC to escape Nebuchadnezzar. This wave also included Jews fleeing from the Babylonian takeover of Judah. In both cases the Sabeans are assumed to have departed later from Ethiopia to Yemen.

According to Menachem Waldman, a major wave of immigration from the Kingdom of Judah to Kush and Abyssinia dates back to the Assyrian Siege of Jerusalem, in the beginning of the 7th century BC. Rabbinic accounts of the siege assert that only about 110,000 Judeans remained in Jerusalem under King Hezekiah's command, whereas about 130,000 Judeans led by Shebna had joined Sennacherib's campaign against Tirhakah, king of Kush. Sennacherib's campaign failed and Shebna's army was lost "at the mountains of darkness", suggestively identified with Semien Mountains.

In 1987 Steven Kaplan wrote:

Although we don't have a single fine ethnographic research on Beta Israel, and the recent history of this tribe has received almost no attention by researchers, every one who writes about the Jews of Ethiopia feels obliged to contribute his share to the ongoing debate about their origin. Politicians and journalists, Rabbis and political activists, not a single one of them withstood the temptation to play the role of the historian and invent a solution for this riddle.

Richard Pankhurst summarized the state of knowledge on the subject in 1992 as follows: "The early origins of the Falashas are shrouded in mystery, and, for lack of documentation, will probably remain so for ever."

By 1994 modern scholars of Ethiopian history and Ethiopian Jews generally supported one of two conflicting hypotheses, as outlined by Kaplan:

- An ancient Jewish origin of the Beta Israel, as well as some ancient Jewish traditions later conserved by the Ethiopian Church. Kaplan lists Simon D. Messing, David Shlush, Michael Corinaldi, Menachem Waldman, Menachem Elon and David Kessler as supporters of this hypothesis.

- A late ethnogenesis of the Beta Israel between the 14th to 16th centuries, from a sect of Ethiopian Christians who took on Biblical practices, and came to see themselves as Jews. Steven Kaplan lists himself along with G. J. Abbink, Kay K. Shelemay, Taddesse Tamrat and James A. Quirin as supporters of this hypothesis. Quirin differs from his fellow researchers in the weight he assigns to an ancient Jewish element that the Beta Israel have conserved.

Paul B. Henze supported the latter view in his 2000 work Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia:

These groups came into conflict with the military colonies and Christian missions which were the main instruments of the extension southward of the Ethiopian state. They may have been joined by dissident or rebelling northern Christians who felt their interpretations of ritual, sacred texts and traditions of art represented a more ancient Israelite connection than Orthodox Monophysite Christianity itself. The Beta Israel can thus be understood as a manifestation of the kind of rebellious archaism that has often come to the surface in Christianity—e.g. Russian Old Believers and German Old Lutherans. Assertion of Jewish derivation, they felt, provided them with a stronger claim to legitimacy than their Christian enemies.

DNA evidence

A 1999 study by Lucotte and Smets studied the DNA of 38 unrelated Beta Israel males living in Israel and 104 Ethiopians living in regions located north of Addis Ababa and concluded that "the distinctiveness of the Y-chromosome haplotype distribution of the Beta-Israel from conventional Jewish populations and their relatively greater similarity in haplotype profile to non-Jewish Ethiopians are consistent with the view that the Beta Israel people descended from ancient inhabitants of Ethiopia and not the Levant." This study confirmed the findings of a 1991 study by Zoossmann-Disken et al. A 2000 study by Hammer et al. of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes of Jewish and non-Jewish groups suggested that "paternal gene pools of Jewish communities from Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East descended from a common Middle Eastern ancestral population", with the exception of the Beta Israel, who were "affiliated more closely with non–Beta Israel Ethiopians and other East Africans." A 2004 study by Shen et al. reached similar conclusions, that the Beta Israel were likely descended from local Ethiopian populations.

A 2001 study by the Department of Biological Sciences at Stanford University found a possible genetic similarity between 11 Ethiopian Jews and four Yemenite Jews who took part in the testing. The differentiation statistic and genetic distances for the 11 Ethiopian Jews and four Yemenite Jews tested were quite low, among the smallest of comparisons involving either of these populations. The four Yemenite Jews from this study may be descendants of reverse migrants of African origin who crossed Ethiopia to Yemen. The study result suggests gene flow between Ethiopia and Yemen as a possible explanation for the closeness. The study also suggests that the gene flow between Ethiopian and Yemenite Jewish populations may not have been direct, but instead could have been between Jewish and non-Jewish populations of both regions.

A 2002 study of mitochondrial DNA (which is passed through only maternal lineage to both men and women) by Thomas et al. showed that the most common mtDNA type found among the Ethiopian Jews sample was present only in Somalia. This further supported the view that all Ethiopian Beta Israel were of local or Ethiopian origin.

A 2009 study of autosomal DNA (which is inherited from both parents) by Tishkoff et al. observed that the Beta Israel were predominantly of the Cushitic genetic cluster, typically found in populations from East Africa. Furthermore, the Beta Israel had elevated levels of the European genetic cluster compared to the other examined Ethiopian and East African populations in the Global Structure Run.

A 2010 study by Behar et al. on the genome-wide structure of Jews observed that the Beta Israel had similar levels of the Middle Eastern genetic clusters as the Semitic-speaking Tigreans and Amharas. Indeed, compared to the Cushitic-speaking Oromos, who are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, the Beta Israel had higher levels of Middle Eastern admixture.

A number of other DNA studies have been done on the Beta Israel.

A 2012 study showed that although they more closely resemble the indigenous populations of Ethiopia, the Beta Israel have some distant Jewish ancestry, going back 2,000 years. This has resulted in speculation that the community was founded by a few Jewish itinerants who moved to Ethiopia, converted locals to Judaism, and married into the local population. This evidence has been used as an explanation as to why the Beta Israel had no idea about the holiday of Hanukkah until being airlifted to Israel - the holiday commemorates events in the 2nd century BC, long after their ancestors had already left Israel.

History

Political independence

Main article: Kingdom of SemienIn the 4th century the Kingdom of Axum converted to Christianity and subsequent dispute arose between the government and the rebels were referred to as "Beta Israel" at the top of the rebels was Phinehas, a descendant of Gideon and his successor. Pinchas Jewish rebels fled to the mountains where they established re-sign their own kingdom. address this period describes tax submission and uploading of Jasmine Axum.

In Gideon and under his descendants ("Gideon") began to take shape populations Jewish tribes. According to Gideon dynasty community perception is true because the Solomon dynasty that West Judaism, unlike the Ethiopian dynasty has accepted the yoke of Christianity and therefore not legitimate. Because this approach were Jews Beta Israel kingdom rebels to Ethiopia.

In the 6th century another change point occurred between Christians and Jews after which separated the two communities. in the late 9th century Jewish traveler, visited the area and described Eldad Hadani independent Jewish kingdom fights against its neighbors foreignness. 10th century Jewish Jews under Abyssinian invasion repelled, Axum conquered the pagan allies aid of agave and imposed their rule for about 40 years. Half of the 12th century dynasty came to power in Ethiopia and their time Zagooh Ethiopian invasion began Gideon areas, the expansion was to Bagmdir on the eastern coast of Lake Tana. at the end of the century Benjamin of Tudela reported on the Jews of the area "and not under the yoke of nations" fight against the kingdom Christian Nubia and the end of the 13th century, Marco Polo also reported on the Jews in the region.

At the end of the 13th century Solomon dynasty came to power and began to establish itself through campaigns and dissemination of occupation pagan kingdoms Christian, Muslim and Jewish. In the 14th century was a Christian missionary activity among Jews Eva Gideon areas outside churches and monasteries were built in their midst. That century, invaded Ethiopian Jews who were in the areas of Gideon and captured the remaining Mbagmdir, you and your lives, Dabie and to establish military outposts were established occupation Vsklt and Gondar. Following this, the Jews revolted and was firmly quashed and the response increased missionary activity in the region. By the 15th century occurred in similar warm-up is conducted Schwager one of the most stubborn fighting after which expenses were cut flashes and many Christian centers. More clashes between the two sides continued intermittently until the invasion Garen which was cooperation against a common enemy.

The late 16th century began to move their capital Ethiopians traveling to areas Gideon, originally derives Sbamfrz then Lgorgora then Lgomngh both Dabie. Transfer of capital involved in the process Amhariztzih and conversion of Jews and pagans locals. Jews, led by the independent Jewish center marked the alienation felt threatened Ethiopian center in their area and began several military responses, these systems, some of which were successful, were cruelly suppressed and encouraged the Ethiopians to move the capital to the heart of Jewish settlement. The early 17th century occurred in the last Jewish war which occupied sign, the Jewish king was exiled Loonatz'i, some royalty Try Macquarie and issued orders to exterminate the Jews and Judaism.

Gondar period

Revival period canceled orders and established the city of Gondar in the heart of the Jewish area between the segregation policy was introduced ethnic groups - religious. From this point on Beta Israel began to integrate into society due to Abyssinian Bvenaot skills, blacksmithing, pottery, art and weaving, some subjects were considered contemptible in the eyes of Ethiopians. Jews joined the military, economic and political, and became the group affects decisions under imperial protection they received. At the same time in the traditional Gideon Hamhariztzih process continued until the end of the area was a traditional Amharic zone "and an integral part of the Ethiopian Empire. From the end of the 18th century, the empire was a period of judges which provincial governors began to gain power at the expense of the central government and its defense community has disappeared. Later in the period the Jews began to lose their status and identity because Ethiopians were the main occupations honor, the Jewish response was almost severing including Abyssinian social life and keeps to itself.

Mission and regeneration

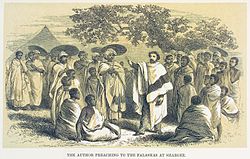

Main articles: Church's Ministry Among Jewish People and Rabbinic JudaismThe early 19th century came to Ethiopia, missionary Samuel Gobat meeting with the Beta Israel and described them. Following this mission delegation organized Gobat community, missionary expedition was launched in 1860 and run by the Church Mission to the Jews, in 1862 the Church of Scotland also sent its mission. Beta Israel cope with them led to their expulsion from their villages and debate about the religious practices of a community, including the offering of sacrifices. In 1862, following the holding messianic community was an attempt to immigrate to Israel that led to the monk Abba Mahari but he failed. In 1868 came Joseph Halevi Beta Israel Diaspora rabbis mission to examine the situation in light of the mission. In the second half of the century occurred in the time of evil, seven consecutive years of drought, wars and epidemics that killed two-thirds of the Jews. Early 20th century was a student of Halevy, Jacob Faitlovitch Ethiopia and thus began a continuous connection between the Diaspora community. At the same time, continued missionary activity. Starting from 1922 onward Faitlovitch Beta Israel to send boys to schools in Europe and in Israel to serve as mentors later and leaders.

During the Italian occupation terminated the relationship with world Jewry. Local government showed a hostile attitude toward the Jews and many of them joined Gideon force Patriotic Movement. Racial laws were published not been kind to the Jews and many were executed for the rebellion. In 1941, orders to carry out the plan for the destruction of the Beta Israel in parallel to the Holocaust, but the defeat of Italy to the Allies Ethiopian Liberation War prevented the exercise instructions.

In 1941, Ethiopia was liberated by Allied forces and Emperor Haile Selassie returned to power. Imperial policy was Amhariztzih various peoples of Ethiopia and accordingly he confirmed to the mission in 1948 to continue its activities in the community.

In the 50's was Faitlovitch entrepreneurship education to the Department of Education and religious culture in exile decides to open schools Beta Israel. In 1953, Rabbi Shmuel Barry was sent as an emissary of the Jewish Agency, the founder of the Hebrew School in Asmara where boys learned priests as well as the rabbinic religion. In 1955 and 1965 come to Israel twenty-seven boys from the community to the village houses. These young talented as messengers return later to villages in Ethiopia and used them as teachers of the Jewish Agency. In 1957 the school closed in Asmara and is transported to the village Aizooh. Graduates of Asmara and Kfar Batya establish additional schools in other villages of the Jews, in 1958 the school transferred Asmara village Ambober, after harassment by their Christian neighbors. Late that year stopped abruptly Agency - sided the contract with its agents in Ethiopia, teaching the successor of Prof. Gevaryahu Jewish Agency and educational activity budget cut by more than half. All schools are closed except for Ambober. Delay continued and the Jewish Agency proposed to transfer the treatment of Jews unidentified factors directly with Israel. In 1961, succeeds Professor Norman Bentwich get funding Jewish education company for settlement, later joining forces other Jewish organizations including the Association for the benefit of the Falashas and Joint. In the 70 ORT established a rural community school operated until 1981, when the Ethiopian government ordered the network to stop the educational activity.

June 1999 over the rise of Kwara Jews to Israel, and with it the presence of the Beta Israel in Ethiopia.

Religion

Main article: HaymanotHaymanot (Ge'ez: ሃይማኖት) is the colloquial term of the Jewish religion in the community.

Mäṣḥafä Kedus (Holy Scriptures) is the name for the religious literature. The language of the writings is Ge'ez. The holiest book is the Orit (from Aramaic "Oraita" - "Torah") which consists of the Five Books of Moses and the books Joshua, Judges and Ruth. The rest of the Bible has secondary importance. The Book of Lamentations is not part of the canon.

M???af? Kedus (Holy Scriptures) is the name for the religious literature. The language of the writings is Ge'ez. The holiest book is the Orit (from Aramaic "Oraita" - "Torah") which consists of the Five Books of Moses and the books Joshua, Judges and Ruth. The rest of the Bible has secondary importance. The Book of Lamentations is not part of the canon.

Deuterocanonical books that also make up part of the canon are Sirach, Judith, Esdras 1 and 2, Meqabyan, Jubilees, Baruch 1 and 4, Tobit, Enoch and the testaments of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

- Orait: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges and Ruth.

- Books of Kings: 1 Kings, 2 Kings, 3 Kings and 4 Kings.

- Books of Solomon: 1 Proverbs, 2 Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Wisdom and Song of Songs.

- Minor Prophets: Amos, Habakkuk, Haggai, Hosea, Jonah, Joel, Malachi, Micah, Nahum, Obadiah, Zephaniah and Zechariah.

- Testaments: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Aaron and Moses.

- Other Books: Psalms, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Job, Esther, 1 Chronicles, 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Sirach, Judith, Tobit, 1 Esdras, Meqabyan, Enoch, Jubilees, Nagara Muse, Baruch and 4 Esdras.

Non-Biblical writings Include: Nagara Muse (The Conversation of Moses), Mota Aaron (Death of Aharon), Mota Muse (Death of Moses), Te'ezaza Sanbat (Precepts of Sabbath), Arde'et (Students), Gorgorios, Mäṣḥafä Sa'atat (Book of Hours), Abba Elias (Father Elija), Mäṣḥafä Mäla'əkt (Book of Angels), Mäṣḥafä Kahan (Book of Priest), Dərsanä Abrəham Wäsara Bägabs (Homily on Abraham and Sarah in Egypt), Gadla Sosna (The Acts of Susanna) and Baqadāmi Gabra Egzi'abḥēr (In the Beginning God Created). Zëna Ayhud (Jews Story) and fālasfā (Philosophers) are two books that are not holy but still have a great influence.

Culture

Main article: Habesha CultureLanguages

Main articles: Agaw languages and Ethiopian Semitic languagesThe Beta Israel once spoke Qwara and Kayla, an Agaw languages. Now they speak Amharic and Tigrinya, both Semitic languages. Their liturgical language is Ge'ez, also Semitic. Since the 1950s, they have taught Hebrew in their schools; in addition, those Beta Israel currently residing in the State of Israel use Hebrew as a daily language.

Economy

Society

Converts

Falash Mura

Main article: Falash Mura

Falash Mura is the name given to those of the Beta Israel community in Ethiopia who converted to Christianity under pressure from the mission during the 19th century and the 20th century. This term consists of Jews who did not adhere to Jewish law, as well as Jewish converts to Christianity, who did so either voluntarily or who were forced to do so.

Many Ethiopian Jews whose ancestors converted to Christianity have been returning to the practice of Judaism. The Israeli government can thus set quotas on their immigration and make citizenship dependent on their conversion to Orthodox Judaism.

Beta Abraham

Main article: Beta AbrahamSlaves

Main articles: Judaism and slavery and Slavery in EthiopiaSlavery was practiced in Ethiopia as in much of Africa until it was formally abolished in 1942. After the slave was bought by a Jew, he went through Giyur and became property of his master.

Relations with world Jewry

9th century - 1790

Bruce, D'Abbadie, Halevy and Faitlovitch

Racial and national discourse

Aliyah to Israel

Early aliyah

Denial of return

Between the years 1965 and 1975 a relatively small group of Ethiopian Jews emigrated to Israel. The Beta Israel immigrants in that period were mainly a very few men who had studied and come to Israel on a tourist visa and then remained in the country illegally.

Several of their supporters in Israel, who recognized their Jewishness decided to assist them. These supporters began organizing in associations, among others under the direction of Ovadia Hazzi, a Yemeni Jew and former sergeant in the Israeli army who was married to a wife from the Beta Israel community since the Second World War. Several of those illegal immigrants managed to get a regularization with the Israeli authorities through the assistance of these support associations. Some agreed to "convert" to Judaism, which helped them to regulate their personal status and thus remain in Israel. People who had got their regularization often brought their families to Israel as well.

In 1973, Ovadia Hazzi officially raised the question of the Jewishness of the Beta Israel to the Israeli Sephardi Rabbi Ovadia Yosef. The rabbi, who cited a rabbinic ruling from the 16th century David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra and asserted that the Beta Israel are descended from the lost tribe of Dan, acknowledged their Jewishness in February 1973. This ruling was initially rejected by the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren, who eventually changed his opinion on the matter in 1974.

Mass aliyah

In April 1975, the Israeli government of Yitzhak Rabin officially accepted the Beta Israel as Jews, for the purpose of the Law of Return (An Israeli act that grants all the Jews in the world the right to immigrate to Israel).

Later on, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin obtained clear rulings from Chief Sephardi Rabbi Ovadia Yosef that they were descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes. The Chief Rabbinate of Israel did however initially require them to undergo pro forma Jewish conversions, to remove any doubt as to their Jewish status.

After a period of civil unrest on September 12, 1974, a pro-communist military junta, known as the "Derg" ("committee") seized power after ousting the emperor Haile Selassie I. The Derg installed a government which was socialist in name and military in style. Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam assumed power as head of state and Derg chairman. Mengistu's years in office were marked by a totalitarian-style government and the country's massive militarization, financed by the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, and assisted by Cuba. Communism was officially adopted by the new regime during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

As a result, the new regime gradually began to embrace anti-religious and anti-Israeli positions as well as showing hostility towards the Jews of Ethiopia.

Towards the mid 1980s Ethiopia underwent a series of famines, exacerbated by adverse geopolitics and civil wars, which eventually resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians, including of the Beta Israel community, became untenable and a large part tried to escape the war and famine to the neighboring Sudan.

The deteriorating situation of the Ethiopian Jews and the real concern for their fate and well-being contributed eventually to the Israeli government's official recognition of the Beta Israel community as Jews in 1975, for the purpose of the Law of Return. These adverse conditions in Ethiopia prompted the Israeli government to airlift most of the Beta Israel population in Ethiopia to Israel in several covert military rescue operations which took place between the 1980s until the early 1990s (see section below).

| Years | Ethiopian-born Immigrants |

Total Immigration to Israel |

|---|---|---|

| 1948–51 | 10 | 687,624 |

| 1952–60 | 59 | 297,138 |

| 1961–71 | 98 | 427,828 |

| 1972–79 | 306 | 267,580 |

| 1980–89 | 16,965 | 153,833 |

| 1990–99 | 39,651 | 956,319 |

| 2000–04 | 14,859 | 181,505 |

| 2005 | 3,573 | 21,180 |

| 2006 | 3,595 | 19,269 |

The emigration to Israel of the Beta Israel community was officially banned by the Ethiopian government, and the Jews began to seek alternative ways of immigration, via Sudan.

- Late 1979 - beginning of 1984 - aliyah activists and Mossad agent operating in Sudan called the Jews to come to Sudan and from Sudan via Europe they were taken to Israel. While they were pose as Ethiopian refugees from the Ethiopian Civil War, Jews began to arrive to the refugee camps in Sudan. Most Jews came from Tigray and Wolqayt, regions that were controlled by the TPLF which often escorted them to the Sudanese border.

- 1983 - March 28, 1985 - this emigration wave was in part motivated by word to mouth reports on the success of the emigration of many Jewish refugees to Israel. In 1983 the governor of Gondar region, Major Melaku Teferra was ousted as governor and his successor removed restrictions on travel. Jews began to arrive in large numbers and the Mossa did not manage to evacuate them in time. Because of the poor conditions in camps, many refugees died of disease and hunger. Among these victims, it is estimated that between 2,000 to 5,000 were Jews. In late 1984, the Sudanese government, following the intervention of the U.S, allowed the emigration of 7,200 Beta Israel refugees to Europe who immediately flew from there to Israel. There two immigration waves were: Operation Moses (original name "The Lion of Judah’s Cub") which took place between 20 November 1984 until January 20, 1985, during which 6,500 people emigrated to Israel. This operation was followed by the Operation Joshua (also referred to as "Operation Sheba") a few weeks later, which was conducted by the U.S Air Force, in which the 494 Jews refugees remaining in Sudan were evacuated to Israel. The second operation was mainly carried out due to the intervention and international pressure very important of the U.S.

- 1990-1991 - After losing Soviet military support due to the collapse of the Eastern bloc, the Ethiopian government allowed the emigration of 6,000 Beta Israel members to Israel in small groups, mostly in hope of establishing ties with the U.S, the allies of Israel. During this time many Beta Israel members flee to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, hoping to escape the civil war in the north of Ethiopia (their region of origin), and hoping to be able to emigrate to Israel. During that period many Beta Israel members crammed into camps on the outskirts of the Addis Ababa waiting to be evacuated to Israel.

- May 24–25, 1991 (Operation Solomon) - In 1991, the political and economic stability of Ethiopia deteriorated, as rebels mounted attacks against and eventually controlled the capital city of Addis Ababa. Worried about the fate of the Beta Israel during the transition period, the Israeli government along with several private groups prepared to continue covertly with the migration. Over the course of the next 36 hours, a total of 34 El Al passenger planes, with their seats removed to maximize passenger capacity, flew 14,325 Beta Israel non-stop to Israel. Again, the operation was mainly carried out due to the intervention and international pressure of the U.S.

- 1992-1999 - During these years, the Qwara Beta Israel emigrated to Israel.

- 1997–present - From 1997 onwards, an irregular emigration began of Falash Mura, which was and still is mainly subjected to political developments in Israel. (see below)

In 1991, the Israeli authorities announced that the emigration of the Beta Israel community to Israel was about to be resolved, thanks to the departure of almost all Jews in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, since then, thousands of people left the northern region of Ethiopia to take refuge in Addis Ababa, declaring themselves Jewish and asking to emigrate to Israel.

As a result, a new term became popularized which was used to refer to this group: "Falash Mura".

These people, who weren't part of the Beta Israel communities in Ethiopia, are not recognized as Jews by the Israeli authorities, and therefore were initially not allowed to emigrate to Israel. The Israeli authorities consider these people either Christian or non-Jewish and therefore states that they are not eligible for Israeli citizenship by the Law of Return.

As a result of the divergent views on the matter a lively debate has risen in Israel on this issue, mainly between the Beta Israel community in Israel and their supporters against the opponents to a potential massive emigration of the Falash Mura people. The government's position on the matter remained quite restrictive, but has been subject to numerous criticisms, including some clerics who want to encourage the return to Judaism of these said groups.

During the 1990s, the Israeli government finally allowed most of those who fled to Addis Ababa to emigrate to Israel. Some did so through the Law of Return, which allows an Israeli parent of a non-Jew help his son or daughter emigrate to Israel, while others were allowed to immigrate to Israel as part of a humanitarian effort.

The Israeli government hoped that by doing so they finally resolved the problem, but instead a new wave of Falash Mura refugees fled to Addis Ababa and demanded to immigrate to Israel. This led the Israeli government to harden its position on the matter in the late 1990s.

In February 2003 the Israeli government decided to accept religious conversions organized by Israeli Rabbis, and that these people can then migrate to Israel as Jewish. Although the new position is more open, and although the Israeli governmental authorities and religious authorities should in theory allow emigration to Israel to most of the Falash Mura wishing to do so (who are recognized as descendants of the Beta Israel community), in practice, however, that immigration remains slow, and the Israeli government continued to limit, from 2003 to 2006, the entry of about 300 Falash Mura immigrants per month.

In April 2005, the Jerusalem Post stated that it had conducted a survey in Ethiopia, after which it was concluded that tens of thousands of Falash Mura still lived in rural northern Ethiopia.

On 14 November 2010 the Israeli cabinet approved a plan to allow 8,000 Falash Mura immigrate to Israel.

In Israel

Main article: Ethiopian Jews in IsraelIn popular culture

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

Over the years, various books and films had their plot focus on the history of the Beta Israel community or had Beta Israel characters who had a prominent role in the plot:

- The 2005 Israeli-French film "Go, Live, and Become" (Hebrew: תחייה ותהייה), directed by Romanian-born Radu Mihăileanu focuses on Operation Moses. The film tells the story of an Ethiopian Christian child whose mother has him pass as Jewish so he can emigrate to Israel and escape the famine looming in Ethiopia. The film was awarded the 2005 Best Film Award at the Copenhagen International Film Festival.

See also

- Ethiopia–Israel relations

- Israeli Jews

- Jews and Judaism in Africa

- Jews of the Bilad el-Sudan (West Africa)

- Letter to the Falashas

- Qemant

- Yemenite Jews

- Jewish ethnic divisions

References

| Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Misplaced Pages's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (November 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics: The Ethiopian Community in Israel

- ‘Wings of the Dove’ brings Ethiopia’s Jews to Israel

- Mozgovaya, Natasha (2008-04-02). "Focus U.S.A.-Israel News - Haaretz Israeli News source". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- The meaning of word "Beta" in the context of social/religious is "community". See James Quirin, The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews, 2010, p. xxi

- Jewish Communities in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries - Ethiopia. Ben-Zvi Institute. p. VII

- Michael Corinaldi, Ethiopian Jewry: Identity and Tradition, Rubin Mass, 1988, p. 186-188 (Hebrew)

- the rescue of ethiopian jews 1978-1990(Hebrew); Ethiopian immigrants and the Mossad met (Hebrew)

- Takuyo Hadane, From Gondar To Jerusalem, p. 91-106 (Hebrew)

- The issue of Falashmura aliyah - follow-up report, Israeli Association for Ethiopian Jews, (Hebrew)

- Israel is losing its sovereignty Ha'aretz.

- Israel "can't bring all Ethiopian Jews at once" - foreign minister. Asia Africa Intelligence Wire (From BBC Monitoring International Reports).

- Israel orchestrates mass exodus of Ethiopians. Knight Ridder/Tribune News Service.

- Families Across Frontiers, p. 391, ISBN 90-411-0239-6

- Ha'aretz.

- James Bruce, Travels To Discover The Source Of The Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and 1773 (in five Volumes), Vol. II, Printed by J. Ruthven for G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1790, p. 485

- "Beta Christian" is the name for the Christian house of prayer in Ethiopia.

- Hagar Salamon, The Hyena People - Ethiopian Jews in Christian Ethiopia, University of California Press, 1999, p.21

- ^ Quirun, The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews, p. 11-15; Aešcoly, Book of the Falashas, p. 1-3; Hagar Salamon, Beta Israel and their Christian neighbors in Ethiopia: Analysis of key concepts at different levels of cultural embodiment, Hebrew University, 1993, p.69-77 (Hebrew); Shalva Weil, "Collective Names and Collective Identity of Ethiopian Jews" in Ethiopian Jews in the Limelight, Hebrew University, 1997, pp. 35-48

- Salamon, Beta Israel, p. 135, n. 20 (Hebrew)

- Budge, Queen of Sheba, Kebra Negast, §§ 38-64.

- Abbink, "The Enigma of Esra'el Ethnogenesis: An Anthro-Historical Study". Cahiers d'Etudes africaines, 120, XXX-4, 1990, pp. 412-420.

- Jankowski, Königin von Saba, 65-71.

- Schoenberger, M. (1975). The Falashas of Ethiopia: An Ethnographic Study (Cambridge: Clare Hall, Cambridge University). Quoted in Abbink, Jon (1990). "The Enigma of Beta Esra'el Ethnogenesis. An Anthro-Historical Study" (PDF). Cahiers d'Études africaines. 30 (120): 397–449.

- Budge, Queen of Sheba, Kebra Negast, chap. 61.

- Ibid., pp. 12-14.

- For a discussion of this theory, see Edward Ullendorff, Ethiopia and the Bible (Oxford: University Press for the British Academy, 1968), pp. 16f, 117. According to Ullendorff, individuals who believed in this origin included President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi of Israel.

- Louis Marcus, "Notice sur l'époque de l'établissement des Juifs dans l'Abyssinie", Journal Asiatique, 3, 1829. see also Herodotus, Histories, Book II, Chap. 30; Strabo, Geographica, Book XVI, Chap. 4 and Book XVII, Chap. 1; Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book VI, Chap. 30

- A.H.M. Jones and Elizabeth Monroe, A History of Ethiopia (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935), p. 40.

- ^ Richard Pankhurst, "The Falashas, or Judaic Ethiopians, in Their Christian Ethiopian Setting", African Affairs, 91 (October 1992), pp. 567-582 at p. 567.

- Pirenne, "La Grèce et Saba après 32 ans de nouvelles recherches", L'Arabie préislamique et son environnement historique et culturel, Colloquium Univ. of Strasbourg, 1987; cf. Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: University Press, 1991), p. 65.

- Menachem Waldman, גולים ויורדים מארץ יהודה אל פתרוס וכוש – לאור המקרא ומדרשי חז'ל, Megadim E (1992), pp. 39-44.

- Steven Kaplan, "The Origins of the Beta Israel: Five Methodological Cautions", Pe'amim 33 (1987), pp. 33-49. (Hebrew)

- ^ Steven Kaplan, On the Changes in the Research of Ethiopian Jewry, Pe'amim 58 (1994), pp. 137–`150. (Hebrew)

- Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time, Palgrave, 2000. p. 55.

- Lucotte, G; Smets, P (1999). "Origins of Falasha Jews studied by haplotypes of the Y chromosome". Human biology. 71 (6): 989–93. PMID 10592688.

- "ethioguide.com". ethioguide.com. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Zoossmann-Diskin, A; Ticher, A; Hakim, I; Goldwitch, Z; Rubinstein, A; Bonne-Tamir, B (1991). "Genetic affinities of Ethiopian Jews". Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 27 (5): 245–51. PMID 2050504.

- Hammer M. F., Redd A. J., Wood E. T., Bonner M. R., Jarjanazi H., Karafet T., Santachiara-Benerecetti S., Oppenheim A., Jobling M. A., Jenkins T., Ostrer H., Bonné-Tamir B. "Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 6 June 2000, vol. 97, no. 12, 6769–6774.

- Shen, Peidong; Lavi, Tal; Kivisild, Toomas; Chou, Vivian; Sengun, Deniz; Gefel, Dov; Shpirer, Issac; Woolf, Eilon; Hillel, Jossi (2004). "Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence Variation". Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248–60. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. PMID 15300852.

- Rosenberg, N. A.; Woolf, E; Pritchard, JK; Schaap, T; Gefel, D; Shpirer, I; Lavi, U; Bonne-Tamir, B; Hillel, J (2001). "Distinctive genetic signatures in the Libyan Jews". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (3): 858–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.3.858. PMC 14674. PMID 11158561.

- Thomas, M; Weale, ME; Jones, AL; Richards, M; Smith, A; Redhead, N; Torroni, A; Scozzari, R; Gratrix, F (2002). "Founding Mothers of Jewish Communities: Geographically Separated Jewish Groups Were Independently Founded by Very Few Female Ancestors". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (6): 1411–20. doi:10.1086/340609. PMC 379128. PMID 11992249.

- Tishkoff, S. A.; Reed, F. A.; Friedlaender, F. R.; Ehret, C.; Ranciaro, A.; Froment, A.; Hirbo, J. B.; Awomoyi, A. A.; Bodo, J.-M. (2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–44. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144. Also see Supplementary Data.

- Behar, Doron M.; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Rosset, Saharon; Parik, Jüri; Rootsi, Siiri; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Kutuev, Ildus (2010). "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people". Nature. 466 (7303): 238–42. doi:10.1038/nature09103. PMID 20531471.

- Lovell, A.; Moreau, C.; Yotova, V.; Xiao, F.; Bourgeois, S.; Gehl, D.; Bertranpetit, J.; Schurr, E.; Labuda, D. (2005). "Ethiopia: Between Sub-Saharan Africa and Western Eurasia". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (3): 275. doi:10.1046/J.1469-1809.2005.00152.x.

- Luis, J; Rowold, D; Regueiro, M; Caeiro, B; Cinnioglu, C; Roseman, C; Underhill, P; Cavallisforza, L; Herrera, R (2004). "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (3): 532–44. doi:10.1086/382286. PMC 1182266. PMID 14973781.

- "Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (5): 752–70. 2004. doi:10.1086/425161. PMC 1182106. PMID 15457403.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Behar, Doron M.; Shlush, Liran I.; Maor, Carcom; Lorber, Margalit; Skorecki, Karl (2006). "Absence of HIV-Associated Nephropathy in Ethiopians". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 47 (1): 88–94. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.023. PMID 16377389.

- Tzur, Shay; Rosset, Saharon; Shemer, Revital; Yudkovsky, Guennady; Selig, Sara; Tarekegn, Ayele; Bekele, Endashaw; Bradman, Neil; Wasser, Walter G. (2010). "Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene". Human Genetics. 128 (3): 345–50. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0861-0. PMC 2921485. PMID 20635188.

- Zoossmann-Diskin, Avshalom (2010). "The origin of Eastern European Jews revealed by autosomal, sex chromosomal and mtDNA polymorphisms". Biology Direct. 5: 57. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-5-57. PMC 2964539. PMID 20925954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - http://in.reuters.com/article/2012/08/06/us-science-genetics-jews-idINBRE8751EI20120806?mlt_click=Master+Sponsor+Logo%28Active%29_19_More+News_sec-col1-m1_News

- Hagar Salamon, "Reflectiotrs of Ethiopian Cultural Patterns on the Beta Israel Absorption in Israel: The "Barya" case" in Steven Kaplan, Tudor Parfitt & Emnuela Trevisan Semi (Editors), Between Africa and Zion: Proceeding of the First International Congress of the Society for the Study of Ethiopian Jewry, Ben-Zvi Institute, 1995, ISBN 978-965-235-058-9, p.126-127

- The Holy Land in history and thought ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. 1988. ISBN 978-90-04-08855-9. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- History of Conflict and Conservation: 1961-1991

- Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, Immigrants, by Period of Immigration, Country of Birth and Last Country of Residence from the Statistical Abstract of Israel 2007-No.58

- Gerrit Jan Abbink, The Falashas In Ethiopia And Israel - The Problem of Ethnic Assimilation, Nijmegen, Institute for Cultural and Social Anthropology, 1984, p. 114

- Mitchell G. Bard, From Tragedy to Triumph: The Politics Behind the Rescue of Ethiopian Jewry, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, p. 137

- Bard, From Tragedy to Triumph, p. 139

- Stephen Spector, Operation Solomon: the daring rescue of the Ethiopian Jews, Page 190.

- (BBC)

- (JTA)

Further reading

|

General

History

Religion

|

Aliyah

Society

|