This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Cat anatomy comprises the anatomical studies of the visible parts of the body of a domestic cat, which are similar to those of other members of the genus Felis.

Mouth

Permanent dentition teeth

Cats are carnivores that have highly specialized teeth. There are four types of permanent dentition teeth that structure the mouth: twelve incisors, four canines, ten premolars and four molars. The premolar and first molar are located on each side of the mouth that together are called the carnassial pair. The carnassial pair specialize in cutting food and are parallel to the jaw. The incisors located in the front section of the lower and upper mouth are small, narrow, and have a single root. They are used for grasping and biting food.

Deciduous dentition teeth

A cat also has a deciduous dentition prior to the formation of the permanent one. This dentition emerges seven days after birth and it is composed of 26 teeth with slight differences. The mouth will have smaller incisors, slender and strongly curved upper canines, vertical lower canines, and even smaller upper and lower molars. Although the upper and lower molars are smaller than the ones that arise during permanent dentition, the similarities are striking.

Tongue

The cat's tongue is covered in a mucous membrane and the dorsal aspect has 5 types of sharp spines, or papillae. The 5 papillae are filiform, fungiform, foliate, vallate, and conical. Papillae allow a cat to groom itself. A cat's sense of smell and taste work closely together, having a vomeronasal organ that allows them to use their tongue as scent tasters, while its longitudinal, transverse, and vertical intrinsic muscles aid in movement.

Ears

"Cat ears" redirects here. For the plant species, see Cat's ear. For kemonomimi, a feature of moe anthropomorphism, see moe anthropomorphism § Animals.

Like dogs, cats have sensitive ears that can move independently of each other. Because of this mobility, a cat can move its body in one direction and point its ears in another direction. The rostral, caudal, dorsal, and ventral auricular muscle groups of each ear comprise fifteen muscles that are responsible for this ability. Most cats have straight, triangular ears that point upward. Unlike with dogs, flap-eared breeds are extremely rare (Scottish Folds have one such exceptional mutation). When angry or frightened, a cat will lay back its ears to accompany the growling or hissing sounds it makes. Cats also turn their ears back when they are playing or to listen to a sound coming from behind them. The fold of skin forming a pouch on the lower posterior part of the ear, known as Henry's pocket, is usually prominent in a cat's ear. Its function is unknown, though it may assist in filtering sounds.

Nose

Cats are highly territorial, and secretion of odors plays a major role in cat communication. The nose helps cats to identify territories, other cats and mates, to locate food, and has various other uses. A cat's sense of smell is believed to be about fourteen times more sensitive than that of humans. The rhinarium (the leathery part of the nose we see) is quite tough, to allow it to absorb rather rough treatment sometimes. The color varies according to the genotype (genetic makeup) of the cat. A cat's skin has the same color as the fur, but the color of the nose leather is probably dictated by a dedicated gene. Cats with white fur have skin susceptible to damage by ultraviolet light, which may cause cancer. Extra care is required when outside in the hot sun.

Legs

Cats are digitigrades, which means that they walk on their toes, just like dogs. The advantage of this is that cats (and other digitigrades) are more agile than other animals. Most animals have ground reaction forces (GRFs) at around two to three times their body weight per limb. But digitigrades have a higher GRF than other animals due to the increased weight on a smaller surface area, which would be about six times their body weight per limb.

Toe tufts are commonly found on cats with medium to long coats. Clumps of fur that stick out at least 1–2 cm (0.4–0.8 in) beyond the paw pad can be considered tufts. In addition to soft paw pads, toe tufts help a cat to silently stalk its prey by muffling excess noise. However, outdoor cats tend to lose their toe tufts due to excessive abrasion on the rougher outdoor surfaces. This is in distinct contrast to indoor cats, who spend most of their time walking on carpet or smooth floors.

Cats are also able to walk very precisely. Adult cats walk with a "four-beat gait", meaning that each foot does not step on the same spot as any other. Whether they walk fast or slowly, a cat's walk is considered symmetric because the right limbs imitate the position of the left limbs as they walk. This type of locomotion provides a sense of touch on all four paws that is necessary for precise coordination.

The cat's vertebrae are held by muscles rather than by ligaments, like humans. This contributes to the cat's elasticity and ability to elongate and contract their back by curving it upwards or oscillating it along their vertebral line.

Cats are also able to jump from greater heights without serious injury, due to the efficient performance of their limbs and ability to control impact forces. In this case, hindlimbs are able to absorb more shock and energy in comparison to the forelimbs, when jumping from surface to surface, as well as steer the cat for weight-bearing and breaking.

Claws

"Cat claw" redirects here. For the superhero, see Cat Claw. For the plant species, see Cat's claw.

Like nearly all members of the family Felidae, cats have protractable claws. In their normal, relaxed position, the claws are sheathed with the skin and fur around the toe pads. This keeps the claws sharp by preventing wear from contact with the ground and allows the silent stalking of prey. The claws on the forefeet are typically sharper than those on the hind feet. Cats can voluntarily extend their claws on one or more paws. They may extend their claws in hunting or self-defense, climbing, "kneading", or for extra traction on soft surfaces (bedspreads, thick rugs, skin, etc.). It is also possible to make a cooperative cat extend its claws by carefully pressing both the top and bottom of the paw. The curved claws can become entangled in carpet or thick fabric, which can cause injury if the cat is unable to free itself.

Most cats have a total of 18 digits and claws: 5 on each forefoot (the 1st digit being the dewclaw), and 4 on each hind foot. The dewclaw is located high on the foreleg, is not in contact with the ground and is non-weight bearing.

Some cats can have more than 18 digits, due to a common mutation called polydactyly or polydactylism, which can result in five to seven toes per paw.

Temperature and heart rate

The normal body temperature of a cat is between 38.3 and 39.0 °C (100.9 and 102.2 °F). A cat is considered febrile (hyperthermic) if it has a temperature of 39.5 °C (103.1 °F) or greater, or hypothermic if less than 37.5 °C (99.5 °F). For comparison, humans have an average body temperature of about 37.0 °C (98.6 °F). A domestic cat's normal heart rate ranges from 140 to 220 beats per minute (bpm), and is largely dependent on how excited the cat is. For a cat at rest, the average heart rate usually is between 150 and 180 bpm, more than twice that of a human, which averages 70 bpm. However, it has been monitored in the wild that cats are often running at higher daily temperatures in order to properly operate and when night falls we see a larger decrease in their body temperature when compared to other cats that might inhabit indoors. The reading on a group of stray cats that was observed in Australia showed a more robust circadian rhythm than a regular house cat.

Skin

Cats possess rather loose skin, which allows them to turn and confront a predator or another cat in a fight, even when it has a grip on them. This is also an advantage for veterinary purposes, as it simplifies injections. In fact, the lives of cats with chronic kidney disease can sometimes be extended for years by the regular injection of large volumes of fluid subcutaneously.

Scruff

The particularly loose skin at the back of the neck is known as the scruff, and is the area by which a mother cat grips her kittens to carry them. As a result, cats tend to become quiet and passive when gripped there. This behavior also extends into adulthood, when a male will grab the female by the scruff to immobilize her while he mounts, and to prevent her from running away as the mating process takes place.

This technique can be useful when attempting to treat or move an uncooperative cat; however, since an adult cat is heavier than a kitten, a pet cat should never be carried by the scruff, but should instead have its weight supported at the rump and hind legs, and at the chest and front paws.

Primordial pouches

The primordial pouch, sometimes referred to as "spay sway" by owners who notice it once the cat has been spayed or neutered, is hereditary in some cats. It is located on a cat's belly. Its appearance is similar to a loose flap of skin that might occur if the cat had been overweight and had then lost weight. It provides a little extra protection against kicks, which are common during cat fights as a cat will try to rake with its rear claws. In wild cats, the ancestors of domesticated felines, this pouch appears to be present to provide extra room in case the animal has the opportunity to eat a large meal and the stomach needs to expand. This stomach pouch also allows the cat to bend and expand, allowing for faster running and higher jumping.

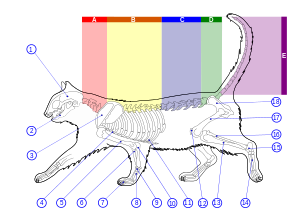

Skeleton

- Cervical or neck bones (7 in number).

- Dorsal or thoracic bones (13 in number, each bearing a rib).

- Lumbar bones (7 in number).

- Sacral bones (3 in number).

- Caudal or tail bones (19 to 21 in number).

- Cranium, or skull.

- Mandible, or lower jaw.

- Scapula, or shoulder-blade.

- Sternum, or breast-bone.

- Humerus.

- Radius.

- Phalanges of the toes.

- Metacarpal bones.

- Carpal or wrist-bones.

- Ulna.

- Ribs.

- Patella, or knee-cap.

- Tibia.

- Metatarsal bones.

- Tarsal bones.

- Fibula.

- Femur, or thigh-bone.

- Pelvis, or hip-bone.

Cats have seven cervical vertebrae like almost all mammals, thirteen thoracic vertebrae (humans have twelve), seven lumbar vertebrae (humans have five), three sacral vertebrae (humans have five because of their bipedal posture), and, except for Manx cats and other shorter tailed cats, twenty-two or twenty-three caudal vertebrae (humans have three to five, fused into an internal coccyx). The extra lumbar and thoracic vertebrae account for the cat's enhanced spinal mobility and flexibility, compared to humans. The caudal vertebrae form the tail, used by the cat as a counterbalance to the body during quick movements. Between their vertebrae, they have elastic discs, useful for cushioning the jump landings.

Unlike human arms, a cat's forelimbs are attached to the shoulders by free-floating clavicle bones, which allow them to pass their body through any space into which they can fit their heads.

Skull

The cat skull is unusual among mammals in having very large eye sockets and a powerful and specialized jaw. Compared to other felines, domestic cats have narrowly spaced canine teeth, adapted to their preferred prey of small rodents.

Spine

A cat's spine can rotate more than the spines of most other animals, and their vertebrae have a special, flexible, elastic cushioning on the disks, which gives it even more flexibility. A flexible spine also contributes to the speed and grace of cats.

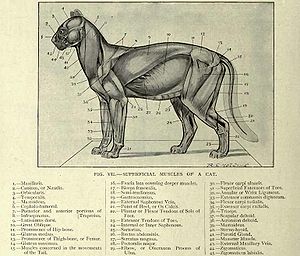

Muscles

Internal abdominal oblique

This muscle's origin is the lumbodorsal fascia and ribs. Its insertion is at the pubis and linea alba (via aponeurosis), and its action is the compression of abdominal contents. It also laterally flexes and rotates the vertebral column.

Transversus abdominis

This muscle is the innermost abdominal muscle. Its origin is the second sheet of the lumbodorsal fascia and the pelvic girdle and its insertion is the linea alba. Its action is the compression of the abdomen.

Rectus abdominis

This muscle is under the extensive aponeurosis situated on the ventral surface of the cat. Its fibers are extremely longitudinal, on each side of the linea alba. It is also traversed by the inscriptiones tendinae, or what others called myosepta.

Deltoid

The deltoid muscles lie just lateral to the trapezius muscles, originating from several fibers spanning the clavicle and scapula, converging to insert at the humerus. Anatomically, there are only two deltoids in the cat, the acromiodeltoid and the spinodeltoid. However, to conform to human anatomy standards, the clavobrachialis is now also considered a deltoid and is commonly referred to as the clavodeltoid.

Acromiodeltoid

The acromiodeltoid is the shortest of the deltoid muscles. It lies lateral to (to the side of) the clavodeltoid, and in a more husky cat it can only be seen by lifting or reflecting the clavodeltoid. It originates at the acromion process and inserts at the deltoid ridge. When contracted, it raises and rotates the humerus outward.

Spinodeltoid

A stout and short muscle lying posterior to the acromiodeltoid. It lies along the lower border of the scapula, and it passes through the upper forelimb, across the upper end of muscles of the upper forelimb. It originates at the spine of the scapula and inserts at the deltoid ridge. Its action is to raise and rotate the humerus outward.

Head

Masseter

The Masseter is a great, powerful, and very thick muscle covered by a tough, shining fascia lying ventral to the zygomatic arch, which is its origin. It inserts into the posterior half of the lateral surface of the mandible. Its action is the elevation of the mandible (closing of the jaw).

Temporalis

The temporalis is a great mass of mandibular muscle, and is also covered by a tough and shiny fascia. It lies dorsal to the zygomatic arch and fills the temporal fossa of the skull. It arises from the side of the skull and inserts into the coronoid process of the mandible. It too, elevates the jaw.

Ocular

Cats have three eyelids. The cat's third eyelid is known as the nictitating membrane. It is located in the inner corner of the eye, which is also covered by conjunctiva. In healthy cats, the conjunctiva of the eyelids is not readily visible and has a pale, pink color.

Integumental

The two main integumental muscles of a cat are the platysma and the cutaneous maximus. The cutaneous maximus covers the dorsal region of the cat and allows it to shake its skin. The platysma covers the neck and allows the cat to stretch the skin over the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles.

Neck and back

Rhomboideus

The rhomboideus is a thick, large muscle below the trapezius muscles. It extends from the vertebral border of the scapula to the mid-dorsal line. Its origin is from the neural spines of the first four thoracic vertebrae, and its insertion is at the vertebral border of the scapula. Its action is to draw the scapula to the dorsal.

Rhomboideus capitis

The Rhomboideus capitis is the most cranial of the deeper muscles. It is underneath the clavotrapezius. Its origin is the superior nuchal line, and its insertion is at the scapula. Action draws scapula cranially.

Splenius

The Splenius is the most superficial of all the deep muscles. It is a thin, broad sheet of muscle underneath the clavotrapezius and deflecting it. It is crossed also by the rhomboideus capitis. Its origin is the mid-dorsal line of the neck and fascia. The insertion is the superior nuchal line and atlas. It raises or turns the head.

Serratus ventralis

The serratus ventralis is exposed by cutting the wing-like latissimus dorsi. The said muscle is covered entirely by adipose tissue. The origin is from the first nine or ten ribs and from part of the cervical vertebrae.

Serratus Dorsalis

The serratus dorsalis is medial to both the scapula and the serratus ventralis. Its origin is via aponeurosis following the length of the mid-dorsal line, and its insertion is the dorsal portion of the last ribs. Its action is to depress and retracts the ribs during breathing.

Intercostals

The intercostals are a set of muscles sandwiched among the ribs. They interconnect ribs, and are therefore the primary respiratory skeletal muscles. They are divided into the external and the internal subscapularis. The origin and insertion are in the ribs. The intercostals pull the ribs backwards or forwards.

Caudofemoralis

The caudofemoralis is a muscle found in the pelvic limb. The Caudofemoralis acts to flex the tail laterally to its respective side when the pelvic limb is bearing weight. When the pelvic limb is lifted off the ground, contraction of the caudofemoralis causes the limb to abduct and the shank to extend by extending the hip joint.

Pectoral

Pectoantebrachialis

Pectoantebrachialis muscle is just one-half-inch wide and is the most superficial in the pectoral muscles. Its origin is the manubrium of the sternum, and its insertion is in a flat tendon on the fascia of the proximal end of the ulna. Its action is to draw the forelimb towards the chest. There is no human equivalent.

Pectoralis major

The pectoralis major, also called pectoralis superficialis, is a broad triangular portion of the pectoralis muscle which is immediately below the pectoantebrachialis. It is smaller than the pectoralis minor muscle. Its origin is the sternum and median ventral raphe, and its insertion is at the humerus. Its action is to draw the forelimb towards the chest.

Pectoralis minor

The pectoralis minor muscle is larger than the pectoralis major. However, most of its anterior border is covered by the pectoralis major. Its origins are ribs three–five, and its insertion is the coracoid process of the scapula. Its actions are the tipping of the scapula and the elevation of ribs three–five.

Xiphihumeralis

The most posterior, flat, thin, and long strip of pectoral muscle is the xiphihumeralis. It is a band of parallel fibers that is found in felines but not in humans. Its origin is the xiphoid process of the sternum. The insertion is the humerus.

Trapezius

In the cat there are three thin flat muscles that cover the back, and to a lesser extent, the neck. They pull the scapula toward the mid-dorsal line, anteriorly, and posteriorly.

Clavotrapezius

The most anterior of the trapezius muscles, it is also the largest. Its fibers run obliquely to the ventral surface. Its origin is the superior nuchal line and median dorsal line and its insertion is the clavicle. Its action is to draw the clavicle dorsally and towards the head.

Acromiotrapezius

Acromiotrapezius is the middle trapezius muscle. It covers the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the scapula. Its origin is the neural spines of the cervical vertebrae and its insertion is in the metacromion process and fascia of the clavotrapezius. Its action is to draw the scapula to the dorsal, and hold the two scapula together.

Spinotrapezius

Spinotrapezius, also called thoracic trapezius, is the most posterior of the three. It is triangular shaped. Posterior to the acromiotrapezius and overlaps latissimus dorsi on the front. Its origin is the neural spines of the thoracic vertebrae and its insertion is the scapular fascia. Its action is to draw the scapula to the dorsal and caudal region.

Digestive system

The digestion system of cats begins with their sharp teeth and abrasive tongue papillae, which help them tear meat, which is most, if not all, of their diet. Cats naturally do not have a diet high in carbohydrates, and therefore, their saliva does not contain the enzyme amylase. Food moves from the mouth through the esophagus and into the stomach. The gastrointestinal tract of domestic cats contains a small cecum and unsacculated colon. The cecum while similar to dogs, does not have a coiled cecum.

The stomach of the cat can be divided into distinct regions of motor activity. The proximal end of the stomach relaxes when food is digested. While food is being digested this portion of the stomach either has rapid stationary contractions or a sustained tonic contraction of muscle. These different actions result in either the food being moved around or the food moving towards the distal portion of the stomach. The distal portion of the stomach undergoes rhythmic cycles of partial depolarization. This depolarization sensitizes muscle cells so they are more likely to contract. The stomach is not only a muscular structure, it also serves a chemical function by releasing hydrochloric acid and other digestive enzymes to break down food.

Food moves from the stomach into the small intestine. The first part of the small intestine is the duodenum. As food moves through the duodenum, it mixes with bile, a fluid that neutralizes stomach acid and emulsifies fat. The pancreas releases enzymes that aid in digestion so that nutrients can be broken down and pass through the intestinal mucosa into the blood and travel to the rest of the body. The pancreas does not produce starch processing enzymes because cats do not eat a diet high in carbohydrates. Since the cat digests low amounts of glucose, the pancreas uses amino acids to trigger insulin release instead.

Food then moves on to the jejunum. This is the most nutrient absorptive section of the small intestine. The liver regulates the level of nutrients absorbed into the blood system from the small intestine. From the jejunum, whatever food that has not been absorbed is sent to the ileum which connects to the large intestine. The first part of the large intestine is the cecum and the second portion is the colon. The large intestine reabsorbs water and forms fecal matter.

There are some things that cats are not able to digest. For example, cats clean themselves by licking their fur with their tongue, which causes them to swallow a lot of fur. This causes a build-up of fur in a cat's stomach and creates a mass of fur. This is often thrown up and is better known as a hairball.

The short length of the digestive tract of the cat causes cats' digestive system to weigh less than other species of animals, which allows cats to be active predators. While cats are well adapted to be predators they have a limited ability to regulate catabolic enzymes of amino acids meaning amino acids are constantly being destroyed and not absorbed. Therefore, cats require a higher protein proportion in their diet than many other species. Cats are not adapted to synthesize niacin from tryptophan and, because they are carnivores, cannot convert carotene to vitamin A, so eating plants while not harmful does not provide them nutrients.

Genitourinary system

See also: Cat § ReproductionFemale genitalia

In the female cat, the genitalia includes the uterus, the vagina, the genital passages and teats. Together with the vulva, the vagina of the cat is involved in mating and provides a channel for newborns during parturition, or birth. The vagina is long and wide. Genital passages are the oviducts of the cat. They are short, narrow, and not very sinuous.

Male genitalia

See also: Penis § FelidaeIn the male cat, the genitalia includes two testicles and the penis, which is covered with small spines.

-

Female genitourinary system

Female genitourinary system

-

Male genitourinary system

Male genitourinary system

-

Male genitourinary system

Male genitourinary system

-

Penile spines

Penile spines

Physiology

| Body temperature | 38.6 °C (101.5 °F) |

| Heart rate | 120–140 beats per minute |

| Breathing rate | 16–40 breaths per minute |

Cats are familiar and easily kept animals, and their physiology has been particularly well studied; it generally resembles those of other carnivorous mammals, but displays several unusual features probably attributable to cats' descent from desert-dwelling species.

Heat tolerance

Cats are able to tolerate quite high temperatures: Humans generally start to feel uncomfortable when their skin temperature passes about 38 °C (100 °F), but cats show no discomfort until their skin reaches around 52 °C (126 °F), and can tolerate temperatures of up to 56 °C (133 °F) if they have access to water.

Temperature regulation

Cats conserve heat by reducing the flow of blood to their skin and lose heat by evaporation through their mouths. Cats have minimal ability to sweat, with glands located primarily in their paw pads, and pant for heat relief only at very high temperatures (but may also pant when stressed). A cat's body temperature does not vary throughout the day; this is part of cats' general lack of circadian rhythms and may reflect their tendency to be active both during the day and at night.

Water conservation

Cats' feces are comparatively dry and their urine is highly concentrated, both of which are adaptations to allow cats to retain as much water as possible. Their kidneys are so efficient, they can survive on a diet consisting only of meat, with no additional water. They can tolerate high levels of salt only in combination with freshwater to prevent dehydration. Mature adult cats become dehydrated when they don't consume 60ml/kg a day, which could lead to health issues involving the bladder and kidneys. Feral cats get most of their water from consuming prey which contain high amounts of water, so they don't actually have to rely on drinking from a water source themselves. The same method is applied to domestic cats, with hydration coming from canned wet foods.

Ability to swim

While domestic cats are able to swim, they are generally reluctant to enter water as it quickly leads to exhaustion.

Urban stressors

Noise

Cats living in human settlements are prone to environmental factors that increase cortisol levels. Cortisol is a stress hormone that impacts physiological aspects of the cats, for example loud sounds and tight spaces, subjection to other animals, unfamiliar people and places. Loud noises such as cars and alarms seem to have the largest impact on rising cortisol levels. High stress response in the body raises blood pressure and causes health issues in cats, such as cardiovascular functioning. A combination of this cardiovascular decline with other factors like obesity from inactive lifestyle and increased heat from urban heat affect can be dangerous for cats, shortening lifespan and quality of life.

Diet adaptation

Cats are innately carnivores and have a genetic tendency to hunt. They carry this trait with them despite environment. Feral cats are domestic but are born and live without much human contact, unlike a pet. Feral cats are closer to pre-industrial cats' lifestyle. Feral cats live off of a natural diet of prey, such as rodents and birds, rather than store-bought foods. This affect is shown in fatty-acid content within the body, with street cats having significantly lower amounts consumed. Consumption of microplastics, a post-industrial common occurrence, is predicted to cause tumors in tissues and blood clots in urban cats, but contents found in studies are conclusively insignificant, given cats' size affecting microplastic particle size consumption and relatively low consumption in general in comparison to humans, which bears little to no effect on cats, including no accumulation over time. This study showed that feral cats get most of their daily energy from protein (52%) and fat (46%), with only a tiny bit from non-fiber carbohydrates (2%). A recent study on what domestic cats choose to eat showed that they like about 52% of their energy from protein, 36% from fat, and 12% from carbs. These results are roughly similar to those for feral cats, suggesting that both domestic and feral prefer a diet close to that of their wild ancestors, though feral cats rely on prey available in their environments and not just processed food. The types of food animals eat play a big role in keeping their stomach's microbial population balanced. Studies have found that having a consistent and varied diet helps with this. When animals eat whole prey, like small animals with bones complete, they are able to extract nutrients from all of the body parts, such as cartilage and collagen. These things can boost gut health, help certain good bacteria grow, and support the immune system. This is different from eating foods mainly made from plants and cooked at high temperatures, which might not have the same benefits; this could be observed in the aforementioned difference in nutrient make up between stray/feral cats and domesticated cats.

Neutering and cortisol levels

Free-roaming cats that are neutered have lower cortisol levels and less aggressive behavior than cats that are unneutered. There seems to be a relationship between stress and aggression with neutering status, possible evolutionary instinctual drive.

See also

References

- Reighard, Jacob; Jennings, H. S. (1901). Anatomy of the cat. New York: H. Holt and Company. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.54000.

- ^ Orsini, Paul; Hennet, Philippe (November 1992). "Anatomy of the Mouth and Teeth of the Cat". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 22 (6): 1265–1277. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(92)50126-7. ISSN 0195-5616. PMID 1455572.

- Noel, Alexis C.; Hu, David L. (4 December 2018). "Cats use hollow papillae to wick saliva into fur" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (49): 12377–12382. doi:10.1073/pnas.1809544115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6298077. PMID 30455290. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- Brown, Sarah (3 March 2020). The Cat. Ivy Press. ISBN 978-1-78240-857-4.

- Hudson, Lola C.; Hamilton, William P. (12 June 2017). Atlas of Feline Anatomy. Teton NewMedia. doi:10.1201/9781315137865. ISBN 978-1-315-13786-5.

- August, John (2009). Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine, Volume 6. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Syufy F. "The Nose Knows Cats' Amazing Sense of Scent". About.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- "Cat Anatomy". cat-chitchat.pictures-of-cats.org. 9 July 2008.

- Miao, Huaibin; Fu, Jun; Qian, Zhihui; Ren, Luquan; Ren, Lei (23 November 2017). "How does the canine paw pad attenuate ground impacts? A multi-layer cushion system". Biology Open. 6 (12): 1889–1896. doi:10.1242/bio.024828. ISSN 2046-6390. PMC 5769641. PMID 29170241.

- Pearcey, Gregory E. P.; Zehr, E. Paul (7 August 2019). "We Are Upright-Walking Cats: Human Limbs as Sensory Antennae During Locomotion". Physiology. 34 (5): 354–364. doi:10.1152/physiol.00008.2019. ISSN 1548-9213. PMID 31389772.

- Cao, Dong-Yuan; Pickar, Joel G.; Ge, Weiginq; Ianuzzi, Allyson; Khalsa, Partap S. (April 2009). "Position sensitivity of feline paraspinal muscle spindles to vertebral movement in the lumbar spine". Journal of Neurophysiology. 101 (4): 1722–1729. doi:10.1152/jn.90976.2008. ISSN 0022-3077. PMC 2695637. PMID 19164108.

- "Cat". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- Wu, Xueqing; Pei, Baoqing; Pei, Yuyang; Wu, Nan; Zhou, Kaiyuan; Hao, Yan; Wang, Wei (18 August 2019). "Contributions of Limb Joints to Energy Absorption during Landing in Cats". Applied Bionics and Biomechanics. 2019: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2019/3815612. PMC 6721424. PMID 31531125. S2CID 202101213.

- Corbee, R.J.; Maas, H.; Doornenbal, A.; Hazewinkel, H.A.W. (1 October 2014). "Forelimb and hindlimb ground reaction forces of walking cats: Assessment and comparison with walking dogs". The Veterinary Journal. 202 (1): 116–127. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.07.001. ISSN 1090-0233. PMID 25155217.

- Armes, Annetta F. (22 December 1900). "Outline of Cat Lessons". The School Journal. LXI: 659. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- "Cats Claws further reading". Cat Talk 101.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Danforth, C. H. (1947). "Heredity of Polydactyly in the Cat". Journal of Heredity. 38 (4): 107–112. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a105701. PMID 20242531.

- "Normal Values For Dog and Cat Temperature, Blood Tests, Urine and other information in ThePetCenter.com". Archived from the original on 13 March 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2005.

- Publishing, Harvard Health. "Normal Body Temperature : Rethinking the normal human body temperature – Harvard Health". harvard.edu. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Cat Health And Cat Metabolism Information For The Best Cat Care. Highlander Pet Center

- Hilmer, Stefanie; Algar, Dave; Neck, David; Schleucher, Elke (1 July 2010). "Remote sensing of physiological data: Impact of long term captivity on body temperature variation of the feral cat (Felis catus) in Australia, recorded via Thermochron iButtons". Journal of Thermal Biology. 35 (5): 205–210. Bibcode:2010JTBio..35..205H. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2010.05.002. ISSN 0306-4565.

- "Vaccinate Your Cat at Home". Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Pictures of Skin Problems in Cats

- "How to Give Subcutaneous Fluids to a Cat". wikihow.com. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- "Scruffing your dog or cat". pets.c. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "What Is the Primordial Pouch in Cats?". Thenest.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Gillis, Rick, ed. (22 July 2002). "Cat Skeleton". Zoolab: A Website for Animal Biology. La Crosse, WI: University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Case, Linda P. (2003). The Cat: Its Behavior, Nutrition, and Health. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. ISBN 0-8138-0331-4.

- Smith, Patricia; Tchernov, Eitan (1992). Structure, Function and Evolution of teeth. Freund Publishing House Ltd. p. 217. ISBN 965-222-270-4.

- Rosenzweig, L. J. (1990). Anatomy of the Cat: Text and Dissection Guide. Wm. C. Brown Publishers Dubuque, IA. p. 110, ISBN 0697055795.

- ^ LLC, Aquanta. "Introduction to the Digestive System of Cats". www.cathealth.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Stevens, C. Edward; Hume, Ian D. (25 November 2004). Comparative Physiology of the Vertebrate Digestive System. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521617147. Retrieved 23 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Cat Digestive System is integral to the absorption of nutrients". cat-health-detective.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Parker, Hilary; Burtka, Allison Torres. "What to Do About Hairballs in Cats". WebMD. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ The cat's genital system and reproduction. aniwa.com

- Aronson, Lester R.; Cooper, Madeline L. (1967). "Penile spines of the domestic cat: Their endocrine-behavior relations" (PDF). The Anatomical Record. 157 (1): 71–78. doi:10.1002/ar.1091570111. PMID 6030760. S2CID 13070242.

- Heide Schatten; Gheorghe M. Constantinescu (21 March 2008). Comparative Reproductive Biology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-39025-2.

- Kahn, Cynthia M.; Line, Scott (2007). Hollander, Joseph Lee (ed.). The Merck/Merial Manual for Pet Health. Merck & Co. ISBN 978-0-911910-99-5.

- ^ MacDonald, M. L.; Rogers, Q. R.; Morris, J. G. (1984). "Nutrition of the domestic cat, a mammalian carnivore". Annual Review of Nutrition. 4: 521–562. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.04.070184.002513. PMID 6380542.

- US National Research Council Subcommittee on Dog and Cat Nutrition (2006). Nutrient Requirements of Dogs and Cats. Washington DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-309-08628-8.

- "How do cats sweat?". CatHealth.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Adams, T.; Morgan, M. L.; Hunter, W. S.; Holmes, K. R. (1970). "Temperature Regulation of the Unanesthetized Cat During Mild Cold and Severe Heat Stress". Journal of Applied Physiology. 29 (6): 852–858. doi:10.1152/jappl.1970.29.6.852. PMID 5485356.

- US National Research Council Committee on Animal Nutrition (1986). Nutrient Requirements of Cats (2nd ed.). Washington DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. doi:10.17226/910. ISBN 978-0-309-03682-5. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010.

- Prentiss, Phoebe G. (1959). "Hydropenia in Cat and Dog: Ability of the Cat to Meet its Water Requirements Solely from a Diet of Fish or Meat". American Journal of Physiology. 196 (3): 625–632. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.196.3.625. PMID 13627237.

- Merck Veterinary Manual

- Tatliağiz, Zeynep; Akyazi, İbrahim (30 April 2023). "Investigation of the effect of water temperature on water consumption of cats". Journal of Istanbul Veterinary Sciences. 7 (1): 50–54. doi:10.30704/http-www-jivs-net.1278513. ISSN 2602-3490.

- Fraser, Andrew F. (2012). Feline Behaviour and Welfare. Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-78064-121-8.

- Cunha Silva, Carina; Fontes, Marco Antônio Peliky (1 August 2019). "Cardiovascular reactivity to emotional stress: The hidden challenge for pets in the urbanized environment". Physiology & Behavior. 207: 151–158. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.05.014. ISSN 0031-9384. PMID 31100295. S2CID 153301091.

- ^ Plantinga, Esther A.; Bosch, Guido; Hendriks, Wouter H. (October 2011). "Estimation of the dietary nutrient profile of free-roaming feral cats: possible implications for nutrition of domestic cats". British Journal of Nutrition. 106 (S1): S35 – S48. doi:10.1017/S0007114511002285. ISSN 1475-2662. PMID 22005434.

- Prata, Joana C.; Silva, Ana L. Patrício; da Costa, João P.; Dias-Pereira, Patrícia; Carvalho, Alexandre; Fernandes, António José Silva; da Costa, Florinda Mendes; Duarte, Armando C.; Rocha-Santos, Teresa (January 2022). "Microplastics in Internal Tissues of Companion Animals from Urban Environments". Animals. 12 (15): 1979. doi:10.3390/ani12151979. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 9367336. PMID 35953968.

- ^ Plantinga, Esther A.; Bosch, Guido; Hendriks, Wouter H. (October 2011). "Estimation of the dietary nutrient profile of free-roaming feral cats: possible implications for nutrition of domestic cats". British Journal of Nutrition. 106 (S1): S35 – S48. doi:10.1017/S0007114511002285. ISSN 1475-2662. PMID 22005434.

- Finkler, H.; Terkel, J. (3 March 2010). "Cortisol levels and aggression in neutered and intact free-roaming female cats living in urban social groups". Physiology & Behavior. 99 (3): 343–347. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.11.014. ISSN 0031-9384. PMID 19954748. S2CID 13112838.

External links

- The cat; an introduction to the study of backboned animals, especially mammals (1881)

- A laboratory guide for the dissection of the cat: An introduction to the study of anatomy (1895)

- Anatomy of the cat (1902)

| Anatomy and morphology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fields |  | |

| Bacteria and fungi | ||

| Protists | ||

| Plants | ||

| Invertebrates | ||

| Mammals | ||

| Other vertebrates | ||

| Glossaries | ||

| Related topics | ||