| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Socially optimal firm size" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The socially optimal firm size is the size for a company in a given industry at a given time which results in the lowest production costs per unit of output.

Discussion

If only diseconomies of scale existed, then the long-run average cost-minimizing firm size would be one worker, producing the minimal possible level of output. However, economies of scale also apply, which state that large firms can have lower per-unit costs due to buying at bulk discounts (components, insurance, real estate, advertising, etc.) and can also limit competition by buying out competitors, setting proprietary industry standards (like Microsoft Windows), etc. If only these "economies of scale" applied, then the ideal firm size would be infinitely large. However, since both apply, the firm must not be too small or too large, to minimize unit costs.

Variation in optimal firm size by industry

The "diseconomies of scale" do not tend to vary widely by industry, but "economies of scale" do. An auto maker has very high fixed costs, which are lower per unit of output the more output is produced. On the other hand, a florist has very low fixed costs and hence very limited sources of economies of scale. Thus there are disparate degrees of economies of scales for different types of organizations.

Effects of agricultural, industrial, and service-based economies on optimal firm size

An industrial society will tend to have large firms, as industry has substantial economies of scale. A service-based economy will favor smaller firms, as services have limited economies of scale. There will, of course, be exceptions, such as Microsoft, which is a huge services company.

Effect of free entry on firm size

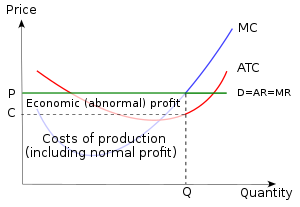

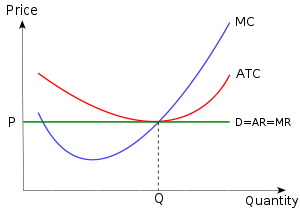

If the market for a product exhibits free entry, meaning that firms can enter (and exit) the market at will with no logistical, legal, or other inhibiting factors, and if firms have U-shaped long-run average cost curves as in the graphs at the right, then in the long run all firms will end up producing at their point of minimum average cost. For suppose a particular firm with the illustrated long-run average cost curve is faced with the market price P indicated in the upper graph. The firm produces at the quantity of output where marginal cost equals marginal revenue (labeled Q in the upper graph), and its per-unit economic profit is the difference between average revenue AR and average total cost ATC at that point, the difference being P minus C in the graph's notation. With firms making economic profit and with free entry, other firms will enter the market for this product, and their additional supply will bring down the market price of the product; this process will continue until there is no longer any economic profit to entice further entrants. The long-run outcome is shown in the second graph, with production by each firm occurring at the newly labelled Q, with marginal cost equalling price at the minimum of the long-run average cost curve, and with the gap between average revenue (the height of the average revenue curve at this Q) and average cost (the height of the average cost curve at this Q) being zero.

Thus with firms possessing U-shaped long-run average cost curves, perfect competition, with (1) firms small enough relative to the overall market that they cannot individually influence the product's market price, and with (2) free entry, leads in the long run to a situation in which no firm is making economic profit, and in which firms are of their socially optimal size (producing at the minimum of their long-run average cost curve).