| |

|---|---|

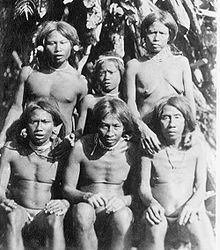

Mixed group of Shompen in 1886 Mixed group of Shompen in 1886 | |

| Total population | |

| 229 (2011 census); or 200-300 (2015 est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Andaman and Nicobar Islands | |

| Languages | |

| Shompen | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nicobarese people Austroasiatic people |

The Shompen or Shom Pen are the Indigenous people of the interior of Great Nicobar Island, part of the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The Shompen are designated as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group within the list of Scheduled Tribe.

Etymology and endonym

"Shompen" is possibly an English mispronunciation of "Shamhap", the Nicobarese name for the tribe. The Shompens living on the western side of the island call themselves Kalay, and those on the eastern side Keyet, with both groups referring to each other as Buavela. A suggestion from 1886 that the Shompen call themselves Shab Daw'a has not been confirmed by modern research.

History of contact

Before the first outside contact with the Shompen in the 1840s, there is no reliable information about these people. Danish Admiral Steen Bille was the first to contact them in 1846 and Frederik Adolph de Roepstorff, a British officer who had already published works on the languages of Nicobar and Andaman, collected ethnographic and linguistic data in 1876. Since then very little has been added to the stock of reliable information on the Shompen, mainly because access to the Nicobar Islands has been restricted for foreign researchers since Indian independence. A polling station was set up in their area for election of 2014. Shompen people for the first time participated in the democratic process. Survival International, a global NGO campaigning for indigenous rights, says that the Shompen are one of the most isolated peoples on earth, with most of them being uncontacted and refusing interactions with outsiders.

Society

In 2001, the population was estimated at approximately 300. Shompen Village-A and Shompen Village-B are home to most Shompens. Before the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the villages were home to 103 and 106 Shompens respectively. However, by the time of 2011 census, only 10 and 44 people were left in these villages respectively.

They practice a hunter-gatherer subsistence economy. In keeping with the tropical climate of the islands, traditional attire includes only clothing below the waist. The traditional attire for men is a short, thin loincloth made of bark cloth, covering only the genitals without a 'tail' of cloth in front. Decoration is limited for men, consisting of bead necklaces and armbands. Women wear a knee-length skirt of bark cloth, occasionally with a shawl of bark cloth covering the shoulders. Decorations include bamboo ear plugs (ahav), bead necklaces (naigaak) and armbands of bamboo (geegap). Both sexes are barefoot. The Shompen probably learned to make and use bows from the Nicobaris. The main weapons are the bow and arrow. They do not use quivers but carry arrows by hand. Numerous types of spears, spear throwers, fire drills and a hatchet are the main tools.

A man usually carried a bow and arrows, a spear and through his loincloth belt, a hatchet, knife and fire drill. The Shompen are a hunter-gatherer subsistence people, hunting wild game such as pigs, birds and small animals while foraging for fruits and forest foods. They also keep pigs and farm yams, roots, vegetables, and tobacco. Shompen huts are built to house 4 people, and villages are made up of 4 to 5 families. Once a child is grown enough, he makes his own hut. The lowland Shompen build their huts on stilts and the walls are made of woven material on a wood frame and the roof of thatched palm fronds, and the structure is raised on stilts. The highland Shompen build their houses on the ground, and the houses are made of the same materials as the raised houses. The interior is covered with mats, with sleeping mats on one end and tools and utensils hung on the walls and rafters. Cooking is done outside.

In the late 1980s, the Shompens were living in ten groups, ranging in size from 2 to 22 individuals, scattered across the interior of the island.

Because of their isolated way of life in the interior of the island, the Shompens were largely protected from the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami that devastated the coastal regions inhabited by Nicobaris and the Indian population.

Language

Little is known about the Shompen languages, of which there are at least two, but they appear to be unrelated to Nicobarese, an isolated group of Austroasiatic languages, and perhaps even to each other. They may constitute a language isolate. Paul Sidwell (2017) classifies Shompen as a Southern Nicobaric language, rather than a separate branch of Austroasiatic.

Threat and Concern

Due to proposed Great Nicobar Development Plan, hectares of land on Great Nicobar Island will be reclaimed to build a "Hong Kong India" with an airport, an international port, and an industrial park. This may impact 1,700 people, including many Shompens. In February 2024, 39 genocide experts from 13 countries warned that the development “will be a death sentence for the Shompen, tantamount to the international crime of genocide”. They said that the proposed population increase and exposure to outside populations would lead to mass deaths, because the Shompen have little to no immunity to infectious outside diseases. This project will also increase the non-local population on the island, which may affect the natives.

See also

References

- ^ "Andaman and Nicobar elections: Shompens vote for the first time". India.com. Press Trust of India. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Singh, Shiv Sahay (1 November 2015). "The less known Shompens of Great Nicobar Island". The Hindu. The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "List of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups" (PDF). tribal.nic.in. Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

- "List of notified Scheduled Tribes" (PDF). Census India. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Weber, George. "The Shompen People". The Andaman Association. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Blench, Roger. "The language of the Shom Pen: a language isolate in the Nicobar islands" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- de Röepstorff, Frederik Adolph (1875). Vocabulary of dialects spoken in the Nicobar and Andaman Isles (2nd ed.). Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-25. Retrieved 2021-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - International, Survival. "Shompen". www.survivalinternational.org. Retrieved 2024-12-19.

- "Press Note: Safety and population profile of the primitive tribes in the andaman and nicobar islands". Ministry of Home Affairs. 2005-01-05. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-08-07.

Maximum Shom Pens population are found in Shompen village (A) & Shompen village (B) with 103 & 106 population respectively.

- "District Census Handbook - Andaman & Nicobar Islands" (PDF). 2011 Census of India. Directorate of Census Operations, Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Sidwell, Paul (2017). "Proto-Nicobarese Phonology, Morphology, Syntax: work in progress" (PDF). International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics 7, Kiel, Sept 29-Oct 1, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- "Proposed Megaproject in Great Nicobar Island Could Spell Trouble for Its People, Wildlife". The Wire. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- Dhillon, Amrit (2024-02-07). "India's plan for untouched Nicobar isles will be 'death sentence' for isolated tribe". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

External links

- "Nicobarese and Shompen". The Andaman Association. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2010.