This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A sentence diagram is a pictorial representation of the grammatical structure of a sentence. The term "sentence diagram" is used more when teaching written language, where sentences are diagrammed. The model shows the relations between words and the nature of sentence structure and can be used as a tool to help recognize which potential sentences are actual sentences.

History

The Reed–Kellogg system was developed by Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg for teaching grammar to students through visualization. It lost some support in the 1970s in the US, but has spread to Europe. It is considered "traditional" in comparison to the parse trees of academic linguists.

Reed-Kellogg system

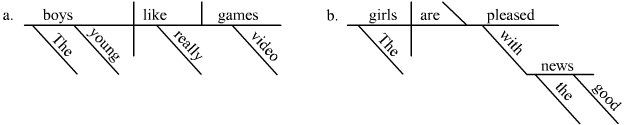

Simple sentences in the Reed–Kellogg system are diagrammed according to these forms:

The diagram of a simple sentence begins with a horizontal line called the base. The subject is written on the left, the predicate on the right, separated by a vertical bar that extends through the base. The predicate must contain a verb, and the verb either requires other sentence elements to complete the predicate, permits them to do so, or precludes them from doing so. The verb and its object, when present, are separated by a line that ends at the baseline. If the object is a direct object, the line is vertical. If the object is a predicate noun or adjective, the line looks like a backslash, \, sloping toward the subject.

Modifiers of the subject, predicate, or object are placed below the baseline:

Modifiers, such as adjectives (including articles) and adverbs, are placed on slanted lines below the word they modify. Prepositional phrases are also placed beneath the word they modify; the preposition goes on a slanted line and the slanted line leads to a horizontal line on which the object of the preposition is placed.

These basic diagramming conventions are augmented for other types of sentence structures, e.g. for coordination and subordinate clauses.

Constituency and dependency

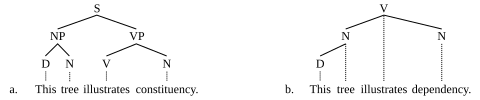

Reed–Kellogg diagrams reflect, to some degree, concepts underlying modern parse trees. Those concepts are the constituency relation of phrase structure grammars and the dependency relation of dependency grammars. These two relations are illustrated here adjacent to each other for comparison, where D means Determiner, N means Noun, NP means Noun Phrase, S means Sentence, V means Verb, VP means Verb Phrase and IP means Inflectional Phrase.

Constituency is a one-to-one-or-more relation; every word in the sentence corresponds to one or more nodes in the tree diagram. Dependency, in contrast, is a one-to-one relation; every word in the sentence corresponds to exactly one node in the tree diagram. Both parse trees employ the convention where the category acronyms (e.g. N, NP, V, VP) are used as the labels on the nodes in the tree. The one-to-one-or-more constituency relation is capable of increasing the amount of sentence structure to the upper limits of what is possible. The result can be very "tall" trees, such as those associated with X-bar theory. Both constituency-based and dependency-based theories of grammar have established traditions.

Reed–Kellogg diagrams employ both of these modern tree generating relations. The constituency relation is present in the Reed–Kellogg diagrams insofar as subject, verb, object, and/or predicate are placed equi-level on the horizontal base line of the sentence and divided by a vertical or slanted line. In a Reed–Kellogg diagram, the vertical dividing line that crosses the base line corresponds to the binary division in the constituency-based tree (S → NP + VP), and the second vertical dividing line that does not cross the baseline (between verb and object) corresponds to the binary division of VP into verb and direct object (VP → V + NP). Thus the vertical and slanting lines that cross or rest on the baseline correspond to the constituency relation. The dependency relation, in contrast, is present insofar as modifiers dangle off of or appear below the words that they modify.

Functional breakdown

A sentence may also be broken down by functional parts: subject, object, adverbial, verb (predicator). The subject is the owner of an action, the verb represents the action, the object represents the recipient of the action, and the adverbial qualifies the action. The various parts can be phrases rather than individual words.

See also

References

- Haussamen, Brock, Amy, Benjamin, Martha, Kolln, Rebecca S., Wheeler, & members of NCTE's Assembly for the Teaching of English Grammar. (2003). Grammar Alive! A Guide for Teachers. National Council of Teachers of English. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/ncte/grammar/

- Hudson, Dick (2014-01-01). "Sentence diagramming". Language Log. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- Reedy, Jeremiah (2003-12-15). "The War Against Grammar (Review)". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 2012-07-04.

- Chomsky, Noam (1957). Syntactic Structures. The Hague/Paris: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Tesnière, Lucien (1959). Éléments de syntaxe structurale (in French). Paris: Klincksieck.

- Aarts, Bas; Haegeman, Liliane (2006). "Ch. 6. 'English Word Classes and Phrases'". In Bas Aarts; Liliane Haegeman (eds.). The Handbook of English Linguistics. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackewell. pp. 117–145. ISBN 9781405187879. OCLC 702267934.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Clark, W. (1847). A practical grammar: In which words, phrases & sentences are classified according to their offices and their various relationships to each another. Cincinnati: H. W. Barnes & Company.

- Reed, A. and B. Kellogg (1877). Higher Lessons in English.

- Reed, A. and B. Kellogg (1896). Graded Lessons in English: An Elementary English Grammar. ISBN 1-4142-8639-2.

- Reed, A. and B. Kellogg (1896). Graded Lessons in English: An Elementary English Grammar Consisting of One Hundred Practical Lessons, Carefully Graded and Adapted to the Class-Room.

Critical sources

- Kitty Burns Florey (2006). Sister Bernadette's Barking Dog. Melville House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-933633-10-7.

- Mazziotta, N. (2016). "Drawing syntax before syntactic trees: Stephen Watkins Clark's sentence diagrams (1847)". Historiographia Linguistica, 43(3), 301–342. doi:10.1075/hl.43.3.03maz.

External links

- Sentence Diagramming by Eugene R. Moutoux

- Grammar Revolution—The English Grammar Exercise Page by Elizabeth O'Brien

- GrammarBrain - Sentence Diagramming Rules

- SenGram, an iPhone and iPad app that presents sentence diagrams as puzzles.

- Diagramming Sentences, including many advanced configurations

- SenDraw, a computer program that specializes in Reed–Kellogg diagrams

- Hefty, Marye; Sallie Ortiz; Sara Nelson (2008). Sentence Diagramming: A Step-by-Step Approach to Learning Grammar Through Diagramming. New York: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 9780205551262. OCLC 127114018.