| |

Headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland Headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland | |

| Formerly | Wilsdorf and Davis (1905–1919) Rolex Watch Co. Ltd (1919–1919) Montres Rolex SA (1919–1920) |

|---|---|

| Company type | Société anonyme |

| Industry | Watchmaking |

| Founded | 1905; 120 years ago (1905) in London |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

| Area served | Worldwide |

| Key people | Jean-Frédéric Dufour (CEO) |

| Products | Watches |

| Production output | |

| Revenue | |

| Owner | Hans Wilsdorf Foundation |

| Number of employees | 7000 |

| Subsidiaries | Montres Tudor SA Bucherer AG |

| Website | rolex.com |

Rolex SA (/ˈroʊlɛks/) is a Swiss watch brand and manufacturer based in Geneva, Switzerland. Founded in 1905 as Wilsdorf and Davis by German businessman Hans Wilsdorf and his brother-in-law Alfred Davis in London, the company registered Rolex as the brand name of its watches in 1908 and became Rolex Watch Co. Ltd. in 1915. After World War I, the company moved its base of operations to Geneva because of the unfavorable economy in the United Kingdom. In 1920, Hans Wilsdorf registered Montres Rolex SA in Geneva as the new company name (montre is French for watch); it later became Rolex SA. Since 1960, the company has been owned by the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, a private family trust.

Rolex SA and its subsidiary Montres Tudor SA design, make, distribute, and service wristwatches sold under the Rolex and Tudor brands. In 2023, Rolex agreed to acquire its longtime retail partner Bucherer, and in 2024, Rolex began construction of a new headquarters on Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, near Billionaires' Row.

History

Early history

Alfred Davis and his brother-in-law Hans Wilsdorf founded Wilsdorf and Davis, the company that would eventually become Rolex SA, in London in 1905. Wilsdorf and Davis's main commercial activity at the time involved importing Hermann Aegler's Swiss movements to England and placing them in watch cases made by Dennison and others. These early wristwatches were sold to many jewellers, who then put their own names on the dial. The earliest watches from Wilsdorf and Davis were usually hallmarked "W&D" inside the caseback.

In 1908, Wilsdorf registered the trademark "Rolex", which became the brand name of watches from Wilsdorf and Davis. He opened an office in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. Wilsdorf wanted the brand name to be easily pronounceable in any language, and short enough to fit on the face of a watch. He also thought that the name "Rolex" was onomatopoeic, sounding like a watch being wound.

During World War I, Rolex manufactured trench watches. In November 1915, the company changed its name to Rolex Watch Co. Ltd. In 1919, Hans Wilsdorf moved the company from England to Geneva, Switzerland, because of heavy post-war taxes levied on luxury imports and high export duties on the silver and gold used for the watch cases. In 1919 the company's name was officially changed to Montres Rolex SA and later in 1920 to Rolex SA.

With administrative worries attended to, Wilsdorf turned the company's attention to a marketing challenge: the infiltration of dust and moisture under the dial and crown, which damaged the movement. To address this problem, in 1926 a third-party casemaker produced a waterproof and dustproof wristwatch for Rolex, giving it the name "Oyster". The original patent attributed to Paul Perregaux and Georges Peret, that allowed the watch to be adjusted while maintaining protection from water ingress was purchased by Rolex and heavily marketed. The watch featured a hermetically sealed case which provided optimal protection for the movement.

As a demonstration, Rolex submerged Oyster models in aquariums, which it displayed in the windows of its main points of sale. In 1927, British swimmer Mercedes Gleitze swam the English Channel with an Oyster on her necklace, becoming the first Rolex ambassador. To celebrate the feat, Rolex published a full-page advertisement on the front page of the Daily Mail for every issue for a whole month proclaiming the watch's success during the ten-hour-plus swim.

In 1931, Rolex patented a self-winding mechanism called a Perpetual rotor, a semi-circular plate that relies on gravity to move freely. In turn, the Oyster watch became known as the Oyster Perpetual. The invention of the Perpetual rotor by Rolex in 1931 revolutionized the self-winding watch, as watches were previously not allowed to be wound using a semi-circular plate that moved freely with gravity.

Upon the death of his wife in 1944, Wilsdorf established the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, a private trust, in which he left all of his Rolex shares, ensuring that some of the company's income would go to charity. Wilsdorf died in 1960, and since then the trust has owned and run Rolex SA.

Charitable status

The Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, which privately owns Rolex SA, is a registered Swiss charitable foundation and pays a lower tax rate. In 2011, a spokesman for Rolex declined to provide evidence regarding the amount of charitable donations made by the Wilsdorf Foundation, which brought up several scandals due to the lack of transparency. In Geneva where the company is based, it is said to have gifted, among many things, two housing buildings to social institutions in Geneva.

Subsidiaries

Rolex SA offers products under the Rolex and Tudor brands. Montres Tudor SA has designed, manufactured and marketed Tudor watches since 6 March 1946. Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf conceived Tudor to create a product for authorized Rolex dealers to sell that offered the reliability and dependability of a Rolex, but at a lower price. The number of Rolex watches was limited by the rate that they could produce in-house Rolex movements, thus Tudor watches were originally equipped with third-party standard movements supplied by ETA SA while using Rolex-quality cases and bracelets. Since 2015, Tudor has begun to manufacture watches with in-house movements. The first model introduced with an in-house movement was the Tudor North Flag. Following this, updated versions of the Tudor Pelagos and Tudor Heritage Black Bay have also been fitted with an in-house caliber.

Tudor watches are marketed and sold in most countries around the world. Montres Tudor SA discontinued sales of Tudor-branded watches in the United States in 2004, but Tudor returned to the United States market in the summer of 2013, and to the UK in 2014.

Production

Each Rolex comes with a unique serial number, which can help indicate its approximate production period. Serial numbers were first introduced in 1926 and were issued sequentially, until 1954, when Rolex restarted from #999,999 to #0. In 1987, there was an addition of one letter to a 6-digit serial number and in 2010, to the present date Rolex introduced random serial numbers.

Quartz movements

While Rolex mostly produces mechanical watches, it also participated in development of the original quartz watch movements. Although Rolex has made very few quartz models for its Oyster line, the company's engineers were instrumental in design and implementation of the technology during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1968, Rolex collaborated with a consortium of 16 Swiss watch manufacturers to develop the Beta 21 quartz movement used in their Rolex Quartz Date 5100 alongside other manufactures including the Omega Electroquartz watches. Within about five years of research, design and development, Rolex created the "clean-slate" 5035/5055 movement that would eventually power the Rolex Oysterquartz.

Materials

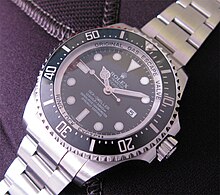

Material-wise, Rolex first used its "Cerachrom" ceramic bezel on the GMT-Master II in 2005, and has since then implemented ceramic bezel inserts across the range of professional sports watches. They are available on the Submariner, Sea Dweller, Deepsea, GMT Master II and Daytona models. In contrast to the aluminum bezel which it replaced, the ceramic bezel color does not wear out from exposure to UV-light and is scratch resistant.

Rolex uses 904L grade stainless steel; in contrast, most Swiss watches are made with 316L grade steel. Rolex uses the higher grade, as it is more resistant to corrosion and when polished, leaves a more attractive lustre.

Notable models

In general, Rolex has three watch lines: Oyster Perpetual, Professional and Cellini (the Cellini line is Rolex's line of "dress" watches). The primary bracelets for the Oyster line are named Jubilee, Oyster, President, and Pearlmaster. The watch straps on the models are usually either stainless steel, yellow gold, white gold, rose gold, or platinum. In the United Kingdom, the retail price for the stainless steel 'Pilots' range (such as the GMT Master II) starts from £9,350. Diamond inlay watches are more expensive. The book Vintage Wristwatches by Antiques Roadshow's Reyne Haines listed a price estimate of vintage Rolex watches that ranged between US$650 and US$75,000, while listing vintage Tudors between US$250 and US$9,000.

Air-Kings

Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf created the Air-Prince line to honor RAF pilots of the Battle of Britain, releasing the first model in 1958. By 2007, the 1142XX iteration of the Air-King featured a COSC-certified movement in a 34mm case, considered by some a miniaturized variant of the 39mm Rolex Explorer as both watches featured very similar styling cues; the 34mm Air-King lineup was the least expensive series of Oyster Perpetual. In 2014 the Air-King was dropped, making the Oyster Perpetual 26/31/34/36/39 the entry-level Rolex line. In 2016 Rolex reintroduced the Air-King, available as a single model (number 116900), largely similar to its predecessors but with a larger 40mm case, and a magnetic shield found on the Rolex Milgauss; indeed the new 40mm Air-King is slightly cheaper than the 39mm Explorer (the Explorer lacks the magnetic shield but its movement has Paraflex shock absorbers that are not found in the Air-King's movement).

Oyster Perpetual

The name of the watch line in catalogs is often "Rolex Oyster ______" or "Rolex Oyster Perpetual ______"; Rolex Oyster and Oyster Perpetual are generic names and not specific product lines, except for the Oyster Perpetual 26/31/34/36/39/41 and Oyster Perpetual Date 34. The Rolex Oyster Perpetual watch is a direct descendant of the original watertight Rolex Oyster watch created in 1926.

Within the Oyster Perpetual lineup, there are three different movements; the 39 features the Calibre 3132 movement with the Parachrom hairspring and Paraflex shock absorbers (the Oyster Perpetual 39 is a variant of the Rolex Explorer 39mm, sharing the same case, bracelet and clasp, bezel, and movement, with a different dial and different hands), while the 34 and 36 models have the Caliber 3130 featuring the Parachrom hairspring, and the smallest 28 and 31 models have Calibre 2231. The Oyster Perpetual Date 34 (or simply Date 34) adds a date display and date movement, plus the options of a white gold fluted bezel and diamonds on the dial.

Certain models from the Date and Datejust ranges are almost identical, however the Datejust have 36 mm and 41 mm cases paired with a 20 mm bracelet, compared with the Date's 34 mm case and 19 mm bracelet. Modern versions of the Oyster Perpetual Date and Datejust models share Rolex's 3135 movement, with the most recent change to the 3135 movement being introduction of Rolex's "parachrom bleu" hairspring, which provides increased accuracy. As the Date and Datejust share a movement, both have the ability to adjust the date forward one day at a time without adjusting the time; this feature is not confined to the Datejust. Compared with the Date, the Datejust has a much wider range of customization options, including other metals beyond stainless steel, various materials for the dial, and optional diamonds on the dial and bezel. The Datejust II, which was released in 2009, has a bigger case (41mm diameter) than the standard Datejust and features an updated movement, being only available in steel with white, yellow or rose gold on an Oyster bracelet. In 2016, Rolex released the Datejust 41, which has the same 41mm diameter case as the Datejust II, however the Datejust 41 has smaller indexes and a thinner bezel compared to the Datejust II

Professional collections

Rolex produced specific models suitable for the extremes of deep-sea diving, caving, mountain climbing, polar exploration, and aviation. Early professional models included the Rolex Submariner (1953) and the Rolex Sea Dweller (1967). The latter watch has a helium release valve to release helium gas build-up during decompression, which, according to Urs Alois Eschle, a former director of Doxa, was patented by Rolex in cooperation with Doxa.

The Explorer (1953) and Explorer II (1971) were developed specifically for explorers who would navigate rough terrain, such as the world-famous Mount Everest expeditions. Indeed, the Rolex Explorer was launched to celebrate the successful ascent of Everest in 1953 by the expeditionary team led by Sir John Hunt. (That expedition was supplied with watches from both Rolex and Smiths; it was a Smiths watch, rather than a Rolex, which Edmund Hillary wore to the summit.)

The 39 mm Rolex Explorer was designed as a "tool watch" for rugged use, hence its movement has Paraflex shock absorbers which give them higher shock resistance than other Rolex watches. The 42mm Rolex Explorer II has some significant differences from the 39mm Explorer; the Explorer II adds a date function, and an orange 24-hour hand which is paired with the fixed bezel's black 24-hour markers for situations underground or around the poles where day cannot be distinguished from night.

Another iconic model is the Rolex GMT Master (1955), originally developed at the request of Pan Am Airways to provide its crews with a dual-time watch that could be used to display local time and GMT (Greenwich Mean Time), which was the international time standard for aviation at that time (and still is in its modern variant of Universal Time Coordinated (UTC) or Zulu Time) and was needed for astronavigation (celestial navigation) during longer flights.

Most expensive pieces

See also: List of most expensive watches sold at auction

- On 26 October 2017, a Rolex Daytona (Ref. 6239) wristwatch, manufactured in 1968, was sold by Phillips in its New York auction for US$17.75 million. The watch was originally purchased by Joanne Woodward in 1968 and was given by Joanne to her husband Paul Newman as a gift. The auction price set a record at $15.5 million, plus buyer's premium of 12.5%, for a final price of $17,752,500 in New York City. As of 2018, it is the most expensive wristwatch and the second most expensive watch ever sold at auction. Notably, "t the time that Newman gave the watch to James Cox , the watch was selling for about $200."

- On 28 May 2018, a Rolex Daytona "Unicorn" Ref. 6265 was sold in auction by Phillips for US$5.937 million in Geneva, making it the second most expensive Rolex timepiece ever sold at auction (as of 2018).

- The most expensive Rolex (in terms of retail price) ever produced by the Rolex factory was the GMT Ice reference 116769TBR with a retail price of US$485,350.

Sponsorship

Since 1976, the Rolex Awards for Enterprise of 100,000 Swiss francs has been awarded; a Young Laureates award of 50,000 was added in 2010. The biennial Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative with a grant of about $41,000 was launched in 2002.

Rolex has been the official timekeeper to the Le Mans 24 Hours motor race since 2001. They also have been Formula 1's official timekeeper between 2013-2024. Former Formula 1 driver Jackie Stewart has advertised Rolex since 1968. Others who have done so for some years include Gary Player, Arnold Palmer, Roger Penske, Jean-Claude Killy, and Kiri Te Kanawa. It is also the sponsor of the Rolex International Jumping Riders Club Top 10 Final competition.

Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh had a specially designed experimental Rolex Oyster Perpetual Deep-Sea Special strapped to the outside of their bathyscaphe during the 1960 Challenger Deep dive to a world-record depth of 10,916 metres (35,814 ft). When James Cameron conducted a similar dive in 2012, a specially designed and manufactured Rolex Oyster Perpetual Sea-Dweller Deep Sea Challenge watch was being "worn" by his submarine's robotic arm.

Mercedes Gleitze was the first British woman to swim the English Channel on 7 October 1927. However, as John E. Brozek (author of The Rolex Report: An Unauthorized Reference Book for the Rolex Enthusiast) points out in his article "The Vindication Swim, Mercedes Gleitze and Rolex take the plunge", some doubts were cast on her achievement when a hoaxer claimed to have made a faster swim only four days later. Hence Gleitze attempted a repeat swim with extensive publicity on 21 October, dubbed the "Vindication Swim". For promotional purposes, Wilsdorf offered her one of the earliest Rolex Oysters if she would wear it during the attempt. After more than 10 hours, in water that was much colder than during her first swim, she was pulled from the sea semi-conscious seven miles short of her goal. Although she did not complete the second crossing, a journalist for The Times wrote, "Having regard to the general conditions, the endurance of Miss Gleitze surprised the doctors, journalists and experts who were present, for it seemed unlikely that she would be able to withstand the cold for so long. It was a good performance." As she sat in the boat, the same journalist made a discovery and reported it as follows: "Hanging round her neck by a ribbon on this swim, Miss Gleitze carried a small gold watch, which was found this evening to have kept good time throughout." When examined closely, the watch was found to be dry inside and in perfect condition. One month later, on 24 November 1927, Wilsdorf launched the Rolex Oyster watch in the United Kingdom with a full front page Rolex advertisement in the Daily Mail.

Achievements

Among the company's notable improvements and innovations are:

- In 1926, Rolex produced the Oyster case. While they claim this was the first reliable waterproof wristwatch case based on a screw-down crown it was not; Depollier's case was patented 8 years earlier. To this end, Rolex acquired the Perragaux-Perret screw-down patent, added a clutch and combined the screw-down crown with a threaded case back and bezel. Wilsdorf even had a specially made Rolex watch (the watch was called the "DeepSea") attached to the side of Trieste, which went to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. The watch survived and tested as having kept perfect time during its descent and ascent. This was confirmed by a telegram sent to Rolex the following day saying "Am happy to confirm that even at 11,000 metres your watch is as precise as on the surface. Best regards, Jacques Piccard". Earlier waterproof watches such as the "Submarine Watch" by Tavannes used other means to seal the case.

- In 1910, the first watchmaker to earn chronometer certification for a small lady wristwatch.

- In 1931, released a wristwatch winding mechanism featuring a rotor, a full 360 degrees rotating weight to power the watch by the movement of the wearer's arm. As well as making watch winding unnecessary, it also kept the power from the mainspring more consistent, resulting in more reliable timekeeping. Fully rotating weights later became part of the standard winding mechanism of self-winding wristwatches. A preceding self-winding mechanism by Harwood instead used a weight that moved in a 270 degrees arc hitting buffer springs on both sides.

- In 1945, introduced the first chronometer wristwatch with an automatically changing date on the dial (Rolex Datejust Ref. 4467). An earlier wristwatch with a date changing mechanism by Mimo was not chronometer certified.

- In 1953, released a case waterproof to 100 m (330 ft) in the Rolex Oyster Perpetual Submariner Ref. 6204. Although this has been commonly publicized as the first diving watch, in 1932 Omega had released the Marine, which could stand 135mts, 35mts more than the 1953 Rolex Submariner. Blancpain produced their Fifty Fathoms watch in 1953, 10 months before the Rolex Submariner.

- In 1954, produced a wristwatch which showed two time zones at once in the Rolex GMT Master ref. 6542. Yet again, it was not the first company to do so, as the Longines DualTime preceded the GMT by a full quarter of a century.

- In 1956, Rolex made a wristwatch with an automatically changing day and date on the dial in the Rolex Day-Date.

Cultural impact

By the start of World War II, Royal Air Force pilots were buying Rolex watches to replace their inferior standard-issue watches; however, when captured and sent to prisoner of war (POW) camps, their watches were confiscated. When Hans Wilsdorf heard of this, he offered to replace all watches that had been confiscated and not require payment until the end of the war, if the officers would write to Rolex and explain the circumstances of their loss and where they were being held. Wilsdorf was in personal charge of the scheme. As a result of this, an estimated 3,000 Rolex watches were ordered by British officers in the officer camp Oflag VII-B in Bavaria alone. This had the effect of raising the morale among the Allied POWs because it indicated that Wilsdorf did not believe that the Axis powers would win the war. American servicemen heard about this when stationed in Europe during WWII and this helped open up the American market to Rolex after the war.

On 10 March 1943, while still a prisoner of war, Corporal Clive James Nutting, one of the organizers of the Great Escape, ordered a stainless steel Rolex Oyster 3525 Chronograph (valued at a current equivalent of £1,200) by mail directly from Hans Wilsdorf in Geneva, intending to pay for it with money he saved working as a shoemaker at the camp. The watch (Rolex watch no. 185983) was delivered to Stalag Luft III on 10 July that year along with a note from Wilsdorf apologising for any delay in processing the order and explaining that an English gentleman such as Corporal Nutting "should not even think" about paying for the watch before the end of the war. Wilsdorf is reported to have been impressed with Nutting because, although not an officer, he had ordered the expensive Rolex 3525 Oyster chronograph while most other prisoners ordered the much cheaper Rolex Speed King model which was popular because of its small size. The watch is believed to have been ordered specifically to be used in the Great Escape when, as a chronograph, it could have been used to time patrols of prison guards or time the 76 ill-fated escapees through tunnel 'Harry' on 24 March 1944. Eventually, after the war, Nutting was sent an invoice of only £15 for the watch, because of currency export controls in England at the time. The watch and associated correspondence between Wilsdorf and Nutting were sold at an auction for £66,000 in May 2007, while at an earlier auction in September 2006 the same watch fetched A$54,000. Nutting served as a consultant for both the 1950 film The Wooden Horse and the 1963 film The Great Escape.

In an infamous murder case, the Rolex on Ronald Platt's wrist eventually led to the arrest of his murderer, Albert Johnson Walker, a financial planner who had fled from Canada when he was charged with 18 counts of fraud, theft and money laundering. When a body was found in the English Channel in 1996 by a fisherman named John Coprik, a Rolex wristwatch was the only identifiable object on the body. Since the Rolex movement had a serial number and was engraved with special markings every time it was serviced, British police traced the service records from Rolex and identified the owner of the watch as Ronald Platt. In addition, police were able to determine the date of death by examining the date on the watch calendar. Since the Rolex movement was fully waterproof and had a reserve of two days of operation when inactive, police were able to reasonably infer the time of death.

In Singapore on 20 April 1998, a 23-year-old Malaysian named Jonaris Badlishah bludgeoned a 42-year-old beautician Sally Poh Bee Eng to death in order to steal her Rolex and later give it to his girlfriend as a birthday present. The case became known as the "Rolex watch murder". Jonaris was arrested, sentenced to death and executed.

O. J. Simpson wore a counterfeit Rolex during his 1994 murder trial.

According to the 2017 Brand Z report, the brand value is estimated at $8.053 billion. Rolex watches continue to have a reputation as status symbols. The company produces more than 1,000,000 timepieces each year.

See also

References

- "Morgan Stanley and LuxeConsult publish Swiss watch industry's top 50 companies for 2023". 28 February 2024. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "History – Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie". www.hautehorlogerie.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "1905–1919". Rolex. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "Hans Wilsdorf – Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie". www.hautehorlogerie.org. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "The Rolex Story – Hans Wilsdorf". www.watchmasters.net. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Company Overview of The Rolex Watch Company Ltd". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "1905–1919". Rolex. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Company Overview of Rolex SA". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Rolex: Secretive and powerful, a canton within a canton". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Stone, Gene (2006). The Watch. Harry A. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3093-5. OCLC 224765439.

- Nooy, Robin (24 August 2023). "Industry News: Rolex Buys Bucherer". Monochrome Watches. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- Rolex To Acquire Watch Retailer Bucherer Archived 27 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine Hypebeast, Dylan Kelly, 24 August 2023

- Natalie Wong. "Chanel Eyes NYC Fifth Avenue Tower That LVMH Is Also Targeting". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

Meanwhile, Swiss watchmaker Rolex is constructing a headquarters building at 665 Fifth Ave.

- ^ "Rolex story". Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- Giorgia Mondani; Guido Mondani (1 January 2015). Rolex Encyclopedia. Guido Mondani Editore e Ass. p. 7. GGKEY:4RFR3GAHPWA. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Liebeskind, David (Fall–Winter 2004). "What Makes Rolex Tick?". Stern Business. New York University Stern School of Business. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- Roderick, Kyle. "'The Watch Book Rolex' Makes Horological History". Forbes. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- Jean, Antoine (1996). "Résistant à l'eau". Archives de l'horlogerie [Horology Archives] (in French). Zürich, Switzerland: Office polytechnique d'édition et de publicité. pp. 126–128.

- ^ "1922–1945". Rolex. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Donze, Pierre-Yves (2011). History of the Swiss Watch Industry : From Jacques David to Nicolas Hayek (2nd ed.). Bern: Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers. ISBN 9783034310215.

- ^ "Privatizing Rolex -- The Fake Tells A Truer Tale". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Deux immeubles offerts au social". 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "Tudor Watches | History | From 1926 to 1949". tudorwatch. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Hans Wildorf's Intuition". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "A Story of Transcendence — Hans Wilsdorf – Revolution". 2 December 2016. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Benjamin Clymer (18 March 2015). "Hands-On: With The New Tudor Pelagos, Now With In-House Movement". Hodinkee. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "Buying A Tudor". Montres Tudor SA. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- Clymer, Benjamin (4 March 2013). "It's Official: Tudor Is Coming Back To The United States, And Soon!". Hodinkee. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "The Complete Guide on Rolex Serial Numbers". The Watch Standard. 24 December 2020. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- "Rolex Serial Numbers & Production Dates Lookup Chart". Bob's Watches. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- "The Quartz Date 5100". oysterquartz.net. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- "The 5035 movement". oysterquartz.net. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ "Materials". Rolex. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Haines, Reyney (12 April 2010). Vintage Wristwatches (Rolex price listing pages 188–204; Tudor price listing pages 221–222). Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-4402-0409-8.

- "The Complete History Of The Rolex Air King". www.rolexmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Telling stories: the Rolex Air–King". HH Journal. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Rolex Air-King 116900 – One of the Most Confusing Rolex Watches". 17 October 2016. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Hands-On: Some Quick Thoughts on the New Rolex Air-King Versus The New Explorer (Live Pics, Official Pricing)". Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Review: The New Rolex Explorer -". 1 May 2016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Jens Koch (24 April 2017). "A Watch for All Seasons: Rolex Oyster Perpetual 39". www.watchtime.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- "Rolex Datejust Watch". Rolex. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Pereztroika, Jose (25 February 2020). "The Doxa HRV". Perezcope. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- Matthew Knight (2 June 2020). "Rolex vs. Smiths: Which Watch Summited Everest in 1953? Putting a Controversy to Rest". The Outdoor Journal. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "Rolex Explorer II Watch: 904L steel – 216570". Rolex. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Paul Newman's 'Paul Newman' Rolex Daytona Sets World Record, Fetches $17.8 Million". Phillips. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Paul Newman watch sells for record $18m". BBC News. 28 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Stevens, Matt (27 October 2017). "Paul Newman Rolex Sells at Auction for Record $17.8 Million". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Phillips: NY080117". Phillips. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Williams, Alex (31 August 2017). "Paul Newman's Rare Rolex Has Auction Watchers Buzzing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Besler, Carol. "Paul Newman's Rolex Sells For Record $17.8-million at Phillips Bacs & Russo Auction in New York". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Slawson, Nicola (28 October 2017). "Paul Newman's Rolex watch sells for record $17.8m". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Bauer, Hyla Ames (14 October 2017). "Paul Newman's 'Paul Newman' Rolex Daytona Sells For $17.8 Million, A Record For A Wristwatch At Auction". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Wolf, Cam (27 October 2017). "The Story Behind Paul Newman's $17.8 Million Rolex Daytona". Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Phillips: CH080318, Rolex". Phillips. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Rolex Cosmograph Daytona "The Unicorn" Reference 6265 Sold For $ 5,936,906". www.gmtpost.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Leung, Ambrose (2 January 2020). "Wrist Check: Cristiano Ronaldo's Latest Timepiece is Rolex's Most Expensive Watch Ever Produced". Hypebeast. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- Tara Paniogue (21 November 2016). "Rolex Awards celebrate 10 honorees during 40th anniversary event in Hollywood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Roslyn Sulcas (9 September 2022). "Mentors Named for Next Class in Rolex Arts Initiative". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- "24 Hours of Le Mans | ACO – Automobile Club de l'Ouest". 24h-lemans.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "Video: Racing Legend Sir Jackie Stewart Talks Rolex At Pebble Beach 2014" Archived 29 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Quill & Pad. 27 August 20014.

- "Rolex Grand Slam of Show Jumping event set to get underway in the Netherlands". 13 March 2019. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Belt, Don. "Trieste: The deepest dive". Rolex. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- "Journey to the bottom of the sea". Rolex. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Stan Czubernat. "The Inconvenient Truth about the World's First Waterproof Watch: The Story of Charles Depollier and his Waterproof Trench Watches of the Great War". LRF Antique Watches. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- Scott Burton (8 August 2021). Mitka Engebretsen (ed.). "It's What's Inside that Counts... but Packaging Matters! A Survey of Notable Wristwatch Case Designs". mitka.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Mécanisme de remontoir pour montres (Self-winding Rotor Patent in French)". Espacenet. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- "Harwood Watches History". Harwood. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- "The Real James Bond Watchstrap Comes to Life". Jake's Rolex Blog. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Rolex GMT-Master". Blowers Jewellers. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Uhrologe. "Longines CEO: We invented the first GMT on behalf of the Sultan". WatchCrunch. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- "Rolex Day-Date". Blowers Jewellers. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Ernesto Gavilanes. "A 'POW Rolex' recalls the Great Escape". Antiquorum.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Time on your hands" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine by James Cockington, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 September 2006

- ^ Times online Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine For sale: Rolex sent by mail order to Stalag Luft III by Bojan Pancevski in Vienna 12 May 2007

- ^ "Picture of the watch and Rolex certificate with Nutting's name". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ Australian auction house Through Internet Archive

- Madoff ‘Prisoner’ Rolex Sale Won’t Calm Swiss Time Town’s Ire Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Quote: "The prisoners involved in the mass breakout from Stalag Luft III in March 1944, depicted in the Steve McQueen film "The Great Escape", may have used the watches to time the movements of guards as they dug tunnels out of the camp, Antiquorum said."

- ^ D'Arcy Jenish, Edward Davenport (15 December 2013). "Walker Money Hunt". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Maclean's, 1998. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Discovery Channel Documentary on Ronald Platt's murder

- "Guilty As Charged: Jonaris Badlishah killed to get a Rolex for girlfriend". The Straits Times. Singapore. 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Simpson's Rolex is a fake, Goldmans find". Articles.latimes.com. 6 October 2007. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- Dillonnews, Nancy (3 October 2007). "Lawyer: O.J.'s Rolex given to Goldman family a fake". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- Branch, Shelly (1 May 1997). "WHY VINTAGE WATCHES SURGED 20% IN THE PAST 18 MONTHS". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- "China: Breaking out the largest logos". Time. 21 September 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Vogel, Carol (6 December 1987). "Modern Conveniences". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Cartner-Morley, Jess (1 December 2005). "What is it with men and their watches?". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- "Rolex on the Forbes World's Most Valuable Brands List". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

Literature

- Pierre-Yves Donzé: La fabrique de l’excellence. Histoire de Rolex. Livreo Alphil, 2024, ISBN 978-2-88950-241-7.

External links

46°11′36″N 6°7′58″E / 46.19333°N 6.13278°E / 46.19333; 6.13278

- about the book (French)