| This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (August 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In materials science, radiation-absorbent material (RAM) is a material which has been specially designed and shaped to absorb incident RF radiation (also known as non-ionising radiation), as effectively as possible, from as many incident directions as possible. The more effective the RAM, the lower the resulting level of reflected RF radiation. Many measurements in electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) and antenna radiation patterns require that spurious signals arising from the test setup, including reflections, are negligible to avoid the risk of causing measurement errors and ambiguities.

Introduction

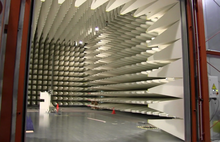

One of the most effective types of RAM comprises arrays of pyramid-shaped pieces, each of which is constructed from a suitably lossy material. To work effectively, all internal surfaces of the anechoic chamber must be entirely covered with RAM. Sections of RAM may be temporarily removed to install equipment but they must be replaced before performing any tests. To be sufficiently lossy, RAM can be neither a good electrical conductor nor a good electrical insulator as neither type actually absorbs any power. Typically pyramidal RAM will comprise a rubberized foam material impregnated with controlled mixtures of carbon and iron. The length from base to tip of the pyramid structure is chosen based on the lowest expected frequency and the amount of absorption required. For low frequency damping, this distance is often 60 cm (24 in), while high-frequency panels are as short as 7.5 to 10 cm (3 to 4 in). Panels of RAM are typically installed on the walls of an EMC test chamber with the tips pointing inward to the chamber. Pyramidal RAM attenuates signal by two effects: scattering and absorption. Scattering can occur both coherently, when reflected waves are in-phase but directed away from the receiver, or incoherently where waves are picked up by the receiver but are out of phase and thus have lower signal strength. This incoherent scattering also occurs within the foam structure, with the suspended carbon particles promoting destructive interference. Internal scattering can result in as much as 10 dB of attenuation. Meanwhile, the pyramid shapes are cut at angles that maximize the number of bounces a wave makes within the structure. With each bounce, the wave loses energy to the foam material and thus exits with lower signal strength.

An alternative type of RAM comprises flat plates of ferrite material, in the form of flat tiles fixed to all interior surfaces of the chamber. This type has a smaller effective frequency range than the pyramidal RAM and is designed to be fixed to good conductive surfaces. It is generally easier to fit and more durable than the pyramidal type RAM but is less effective at higher frequencies. Its performance might however be quite adequate if tests are limited to lower frequencies (ferrite plates have a damping curve that makes them most effective between 30–1000 MHz). There is also a hybrid type, a ferrite in pyramidal shape. Containing the advantages of both technologies, the frequency range can be maximized while the pyramid remains small, about 10 cm (3.9 in).

For physically-realizable radiation-absorbent materials, there is a trade-off between thickness and bandwidth: optimal thickness to bandwidth ratio of a radiation-absorbent material is given by the Rozanov limit.

Use in stealth technology

Radar-absorbent materials are used in stealth technology to disguise a vehicle or structure from radar detection. A material's absorbency at a given frequency of radar wave depends upon its composition. RAM cannot perfectly absorb radar at any frequency, but any given composition does have greater absorbency at some frequencies than others; no one RAM is suited to absorption of all radar frequencies. A common misunderstanding is that RAM makes an object invisible to radar. A radar-absorbent material can significantly reduce an object's radar cross-section in specific radar frequencies, but it does not result in "invisibility" on any frequency.

History

The earliest forms of stealth coating were radar absorbing paints developed by Major K. Mano of the Tama Technical Institute, and Dr. Shiba of the Tokyo Engineering College for the IJAAF. Multiple paint mixtures were tested with ferric oxide and liquid rubber, as well as ferric oxide, asphalt and airplane dope having the best results. Despite success in laboratory tests, the paints saw little practical application as they were heavy and would significantly impact the performance of any aircraft they were applied to.

Conversely the IJN saw great potential in anti-radar materials and the Second Naval Technical Institute began research on layered materials to absorb radar waves rather than paint. Rubber and plastic with carbon powder with varying ratios were layered to absorb and disperse radar waves. The results were promising against 3 GHz (S band) frequencies, but poor against 3 cm wave length (10 GHz, X band) radar. Work on the program was halted due to allied bombing raids, but research was continued post war by the Americans to mild success.

In September of 1944, materials called Sumpf and Schornsteinfeger, coatings used by the German navy during World War II for the snorkels (or periscopes) of submarines, to lower their reflectivity in the 20 cm radar band (1.5 GHz, L band) the Allies used. The material had a layered structure and was based on graphite particles and other semiconductive materials embedded in a rubber matrix. The material's efficiency was partially reduced by the action of sea water.

A related use was planned for the Horten Ho 229 aircraft. The adhesive which bonded plywood sheets in its skin was impregnated with graphite particles which were intended to reduce its visibility to Britain's radar.

Types of radar-absorbent material (RAM)

Iron ball paint absorber

One of the most commonly known types of RAM is iron ball paint. It contains tiny spheres coated with carbonyl iron or ferrite. Radar waves induce molecular oscillations from the alternating magnetic field in this paint, which leads to conversion of the radar energy into heat. The heat is then transferred to the aircraft and dissipated. The iron particles in the paint are obtained by decomposition of iron pentacarbonyl and may contain traces of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen. One technique used in the F-117A Nighthawk and other such stealth aircraft is to use electrically isolated carbonyl iron balls of specific dimensions suspended in a two-part epoxy paint. Each of these microscopic spheres is coated in silicon dioxide as an insulator through a proprietary process. Then, during the panel fabrication process, while the paint is still liquid, a magnetic field is applied with a specific Gauss strength and at a specific distance to create magnetic field patterns in the carbonyl iron balls within the liquid paint ferrofluid. The paint then hardens with the magnetic field holding the particles in their magnetic pattern. Some experimentation has been done applying opposing north–south magnetic fields to opposing sides of the painted panels, causing the carbonyl iron particles to align (standing up on end so they are three-dimensionally parallel to the magnetic field). The carbonyl iron ball paint is most effective when the balls are evenly dispersed, electrically isolated, and present a gradient of progressively greater density to the incoming radar waves. A related type of RAM consists of neoprene polymer sheets with ferrite grains or conductive carbon black particles (containing about 0.30% of crystalline graphite by cured weight) embedded in the polymer matrix. The tiles were used on early versions of the F-117A Nighthawk, although more recent models use painted RAM. The painting of the F-117 is done by industrial robots so the paint can be applied consistently in specific layer thicknesses and densities. The plane is covered in tiles "glued" to the fuselage and the remaining gaps are filled with iron ball "glue." The United States Air Force introduced a radar-absorbent paint made from both ferrofluidic and nonmagnetic substances. By reducing the reflection of electromagnetic waves, this material helps to reduce the visibility of RAM-painted aircraft on radar. The Israeli firm Nanoflight has also made a radar-absorbing paint that uses nanoparticles. The Republic of China (Taiwan)'s military has also successfully developed radar-absorbing paint which is currently used on Taiwanese stealth warships and the Taiwanese-built stealth jet fighter which is currently in development in response to the development of stealth technology by their rival, the mainland People's Republic of China which is known to have displayed both stealth warships and planes to the public.

Foam absorber

Foam absorber is used as lining of anechoic chambers for electromagnetic radiation measurements. This material typically consists of a fireproofed urethane foam loaded with conductive carbon black in mixtures between 0.05% and 0.1% (by weight in finished product), and cut into square pyramids with dimensions set specific to the wavelengths of interest. Further improvements can be made when the conductive particulates are layered in a density gradient, so the tip of the pyramid has the lowest percentage of particles and the base contains the highest density of particles. This presents a "soft" impedance change to incoming radar waves and further reduces reflection (echo). The length from base to tip, and width of the base of the pyramid structure is chosen based on the lowest expected frequency when a wide-band absorber is sought. For low-frequency damping in military applications, this distance is often 60 cm (24 in), while high-frequency panels are as short as 7.5 to 10 cm (3 to 4 in). An example of a high-frequency application would be the police radar (speed-measuring radar K and Ka band), the pyramids would have a dimension around 10 cm (4 in) long and a 5 cm × 5 cm (2 in × 2 in) base. That pyramid would set on a 5 cm x 5 cm cubical base that is 2.5 cm (1 in) high (total height of pyramid and base of about 12.5 cm or 5 in). The four edges of the pyramid are softly sweeping arcs giving the pyramid a slightly "bloated" look. This arc provides some additional scatter and prevents any sharp edge from creating a coherent reflection. Panels of RAM are installed with the tips of the pyramids pointing toward the radar source. These pyramids may also be hidden behind an outer nearly radar-transparent shell where aerodynamics are required. Pyramidal RAM attenuates signal by scattering and absorption. Scattering can occur both coherently, when reflected waves are in-phase but directed away from the receiver, or incoherently where waves may be reflected back to the receiver but are out of phase and thus have lower signal strength. A good example of coherent reflection is in the faceted shape of the F-117A stealth aircraft which presents angles to the radar source such that coherent waves are reflected away from the point of origin (usually the detection source). Incoherent scattering also occurs within the foam structure, with the suspended conductive particles promoting destructive interference. Internal scattering can result in as much as 10 dB of attenuation. Meanwhile, the pyramid shapes are cut at angles that maximize the number of bounces a wave makes within the structure. With each bounce, the wave loses energy to the foam material and thus exits with lower signal strength. Other foam absorbers are available in flat sheets, using an increasing gradient of carbon loadings in different layers. Absorption within the foam material occurs when radar energy is converted to heat in the conductive particle. Therefore, in applications where high radar energies are involved, cooling fans are used to exhaust the heat generated.

Jaumann absorber

A Jaumann absorber or Jaumann layer is a radar-absorbent substance. When first introduced in 1943, the Jaumann layer consisted of two equally spaced reflective surfaces and a conductive ground plane. One can think of it as a generalized, multilayered Salisbury screen, as the principles are similar. Being a resonant absorber (i.e. it uses wave interfering to cancel the reflected wave), the Jaumann layer is dependent upon the λ/4 spacing between the first reflective surface and the ground plane and between the two reflective surfaces (a total of λ/4 + λ/4 ). Because the wave can resonate at two frequencies, the Jaumann layer produces two absorption maxima across a band of wavelengths (if using the two layers configuration). These absorbers must have all of the layers parallel to each other and the ground plane that they conceal. More elaborate Jaumann absorbers use series of dielectric surfaces that separate conductive sheets. The conductivity of those sheets increases with proximity to the ground plane.

Split-ring resonator absorber

Main article: Split-ring resonatorSplit-ring resonators (SRRs) in various test configurations have been shown to be extremely effective as radar absorbers. SRR technology can be used in conjunction with the technologies above to provide a cumulative absorption effect. SRR technology is particularly effective when used on faceted shapes that have perfectly flat surfaces that present no direct reflections back to the radar source (such as the F-117A). This technology uses photographic process to create a resist layer on a thin (about 0.18 mm or 0.007 in) copper foil on a dielectric backing (thin circuit board material) etched into tuned resonator arrays, each individual resonator being in a "C" shape (or other shape—such as a square). Each SRR is electrically isolated and all dimensions are carefully specified to optimize absorption at a specific radar wavelength. Not being a closed loop "O", the opening in the "C" presents a gap of specific dimension which acts as a capacitor. At 35 GHz, the diameter of the "C" is near 5 mm (0.20 in). The resonator can be tuned to specific wavelengths and multiple SRRs can be stacked with insulating layers of specific thicknesses between them to provide a wide-band absorption of radar energy. When stacked, the smaller SRRs (high-frequency) in the range face the radar source first (like a stack of donuts that get progressively larger as one moves away from the radar source) stacks of three have been shown to be effective in providing wide-band attenuation. SRR technology acts very much in the same way that antireflective coatings operate at optical wavelengths. SRR technology provides the most effective radar attenuation of any technologies known previously and is one step closer to reaching complete invisibility (total stealth, "cloaking"). Work is also progressing in visual wavelengths, as well as infrared wavelengths (LIDAR-absorbing materials).

Carbon nanotube

Main article: Carbon nanotubeRadars work in the microwave frequency range, which can be absorbed by multi-wall nanotubes (MWNTs). Applying the MWNTs to the aircraft would cause the radar to be absorbed and therefore seem to have a smaller radar cross-section. One such application could be to paint the nanotubes onto the plane. Recently there has been some work done at the University of Michigan regarding carbon nanotubes usefulness as stealth technology on aircraft. It has been found that in addition to the radar absorbing properties, the nanotubes neither reflect nor scatter visible light, making it essentially invisible at night, much like painting current stealth aircraft black except much more effective. Current limitations in manufacturing, however, mean that current production of nanotube-coated aircraft is not possible. One theory to overcome these current limitations is to cover small particles with the nanotubes and suspend the nanotube-covered particles in a medium such as paint, which can then be applied to a surface, like a stealth aircraft.

See also

References

Notes

- E Knott, J Shaeffer, M Tulley, Radar Cross Section. pp 528–531. ISBN 0-89006-618-3

- Fully compact anechoic chamber using the pyramidal ferrite absorber for immunity test

- Rozanov, K. N. (August 2000). "Ultimate thickness to bandwidth ratio of radar absorbers". IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation. 48 (8): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2000ITAP...48.1230R. doi:10.1109/8.884491.

- "Electronics Targets Japanese Anti-Radar Coverings" (PDF).

- ^ "Electronics Targets Japanese Anti-Radar Coverings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 Oct 2023.

- "The Schornsteinfeger Project" (PDF).

- Hepcke, Gerhard. "The Radar War, 1930–1945" (PDF). Radar World.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The History of Radar". BBC. 2003-07-14.

- Shepelev, Andrei and Ottens, Huib. Ho 229 The Spirit of Thuringia: The Horten All-wing jet Fighter. London: Classic Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-903223-66-0.

- Is it stealthy? Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (Retrieved February 2016)

- "New Stealth Nano-Paint Turns Any Aircraft into a Radar-Evading Stealth Plane". 18 March 2019.

- "Taiwanese military reportedly develops 'stealth' coating – Taipei Times". 5 July 2011.

- "Taiwan to build 'stealth' warship fleet".

- E Knott, J Shaeffer, M Tulley, Radar Cross Section. pp 528–531. ISBN 0-89006-618-3

- Bourzac, Katherine. "Nano Paint Could Make Airplanes Invisible to Radar." Technology Review. MIT, 5 December 2011.

Bibliography

- The Schornsteinfeger Project, CIOS Report XXVI-24.

External links

- Silva, M. W. B.; Kretly, L. C. (October 2011). "A new concept of RAM-Radiation Absorbent Material: Applying corrugated surfaces to improve reflectivity". 2011 SBMO/IEEE MTT-S International Microwave and Optoelectronics Conference (IMOC 2011). pp. 556–560. doi:10.1109/IMOC.2011.6169338. ISBN 978-1-4577-1664-5. S2CID 31245210.

- Kim, Dong-Young; Yoon, Young-Ho; Jo, Kwan-Jun; Jung, Gil-Bong; An, Chong-Chul (2016). "Effects of Sheet Thickness on the Electromagnetic Wave Absorbing Characterization of Li0.375Ni0.375Zn0.25-Ferrite Composite as a Radiation Absorbent Material". Journal of Electromagnetic Engineering and Science. 16 (3): 150–158. doi:10.5515/JKIEES.2016.16.3.150.

- Suppliers of Radar absorbent materials