In pipeline transportation, pigging is the practice of using pipeline inspection gauges or gadgets, devices generally referred to as pigs or scrapers, to perform various maintenance operations. This is done without stopping the flow of the product in the pipeline.

These operations include but are not limited to cleaning and inspecting the pipeline. This is accomplished by inserting the pig into a "pig launcher" (or "launching station")—an oversized section in the pipeline, reducing to the normal diameter. The launching station is then closed and the pressure-driven flow of the product in the pipeline is used to push the pig along the pipe until it reaches the receiving trap—the "pig catcher" (or "receiving station").

Applications

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Pigging is used to clean large diameter pipelines in the oil industry. Today, however, the use of smaller diameter pigging systems is now increasing in many continuous and batch process plants as plant operators search for increased efficiencies and reduced costs.

Pigging can be used for almost any section of the transfer process between, for example, blending, storage or filling systems. Pigging systems are installed in industries handling products as diverse as lubricating oils, paints, chemicals, toiletries, cosmetics and foodstuffs.

Pigs are used in lube oil or paint blending to clean the pipes to avoid cross-contamination, and to empty the pipes into the product tanks (or sometimes to send a component back to its tank). Usually pigging is done at the beginning and at the end of each batch, but sometimes it is done in the midst of a batch, such as when producing a premix that will be used as an intermediate component.

Pigs are also used in oil and gas industries to clean or clear pipelines. Intelligent or "Smart pigs" are used to inspect pipelines to assess their condition and to prevent leaks, which can be hazardous or harmful to the environment. They usually do not interrupt production, though some product can be lost when the pig is removed. They can also be used to separate different products in a multiproduct pipeline and to clear slugs of liquid from multiphase gas//liquid pipelines.

Pigging requires the pipeline to be designed to be pigged from the outset. If the pipeline contains topological variations including changes in diameter, butterfly valves, instrumentation, tight bends, pumps or reduced port ball valves, the pipeline cannot be traditionally pigged. In such instances, alternatives such as Ice Pigging may be employed. Full port (or full bore) ball valves cause no problems because the inside diameter of the ball opening is the same as that of the pipe.

Etymology

Some early cleaning "pigs" were made from straw bales wrapped in barbed wire while others used leather. Both made a squealing noise while traveling through the pipe, sounding to some like a pig squealing, which gave pigs their name.

In production environments

Product and time saving

A major advantage for multi-product pipelines of piggable systems is the potential of product savings. At the end of each product transfer, it is possible to segregate the next products using a pigging sphere. Alternatively it is possible to clear out the entire line contents with the pig, either forwards to the receipt point, or backwards to the source tank. There is no requirement for extensive line flushing.

Without the need for line flushing, pigging offers the additional advantage of much more rapid and reliable product changeover. Product sampling at the receipt point is faster with pigs, because the interface between products is very clear; the old method of checking at intervals to determine where the product is on-specification takes considerably longer.

Pigging can also be operated totally by a programmable logic controller (PLC).

Environmental benefits

Pigging has a significant role to play in reducing the environmental impact of batch operations. Traditionally, the only way that an operator of a batch process could ensure a product was completely cleared from a line was to flush the line with a cleaning agent such as water or a solvent, or even with the next product. The cleaning agent then had to be subjected to effluent treatment or solvent recovery. If a product was used to clear the line, it was necessary to downgrade or dump the contaminated portion of the product. All of these problems can now be eliminated due to the very precise interface produced by modern pigging systems.

Safety considerations

Pigging systems are designed so that the pig is loaded into the launcher, which is pressured to launch the pig into the pipeline through a kicker line. In some cases, the pig is removed from the pipeline via the receiver at the end of each run. All systems must allow for the receipt of pigs at the launcher, as blockages in the pipeline may require the pigs to be pushed back to the launcher. Many systems are designed to pig the pipeline in either direction.

The pig is pushed either with a gas or a liquid; if pushed by gas, some systems can be adapted in the gas inlet in order to ensure pig's constant speed, whatever the flow pressure is. The pigs must be removed, as many pigs are rented, pigs wear and must be replaced, and cleaning (and other) pigs push contaminants from the pipeline such as wax, foreign objects, hydrates, etc., which must be removed from the pipeline. There are inherent risks in opening the barrel to atmospheric pressure so care must be taken to ensure that the barrel is depressurized prior to opening. If the barrel is not completely depressurized, the pig can be ejected from the barrel and operators have been severely injured when standing in front of an open pig door. A pig was once accidentally shot out of the end of a pipeline without a proper pig receiver and went through the side of a house 150 metres (500 ft) away. When the product is sour, the barrel should be evacuated to a flare system where the sour gas is burnt. Operators should wear a self-contained breathing apparatus when working on sour systems.

A few pigging systems utilize a "captive pig", and the pipeline is only opened occasionally to check the condition of the pig. At all other times, the pig is shuttled up and down the pipeline at the end of each transfer, and the pipeline is never opened up during process operation. These systems are not common.

Pigging operations

See diagram on the right representing a pig launcher. In normal operation valves V2 and V4 will be open, all other valves and the door are closed and locked.

To launch a pig

- Ensure pig launcher is drained and vented. Unlock and open, then close and relock the vent and drain valves.

- Unlock and open door, load pig into launcher, close and lock door.

- Unlock and open valves V1 and V3, to create a flow path through the launcher.

- Partly close ‘kicker’ valve V2 to launch the pig.

- The launch alarm XA will indicate when the pig has been launched.

- Open valve V2 fully.

- Close and lock valves V1 and V3.

- Unlock and open vent and drain valves. Allow launcher to depressurise and drain.

- Close and lock vent and drain valves.

- Pig launcher is then ready for the next pig to launch.

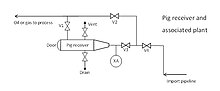

See diagram on the right representing a pig receiver.

To receive a pig

- Unlock and open valves V1 and V3, to create a flow path through the pig receiver.

- Partly close ‘kicker’ valve V2 to induce flow through the receiver.

- The receive alarm XA will indicate when the pig has been received.

- Open valve V2 fully.

- Close and lock valves V1 and V3.

- Unlock and open vent and drain valves to empty the receiver.

- Close and lock vent and drain valves.

- Unlock and open door, remove pig from receiver, close and lock door.

- Pig receiver is then ready to receive the next pig.

The pigging installation shown (right) is known as an Above Ground Installation (AGI). It is part of the UK's National Transmission System for natural gas. It shows two pig launcher/ receivers at the end of two 610-millimetre (24 in) diameter pipelines that carry gas under the River Thames, between East Tilbury in Essex and Shorne in Kent. Should one pipeline be damaged, by a ship's anchor for example, that line can be isolated and the second pipeline allows gas to flow across the river.

Mechanical interlocks

There are many reports of incidents in which operators have been injured or even killed while performing a pigging operation. Common causes of such events are:

- opening of the closure door while the vessel is still pressurized;

- opening of the main process valve while the closure door is not fully closed;

- opening of the closure door while a high concentration of H₂S or other toxins remains inside the vessel;

- the vent valve remaining open while the vessel is being pressurized with its medium.

All these causes are directly related to improper operation of the process valves and the closure door. A common method of avoiding these kinds of incidents is to add valve interlocks, which has been adopted by all global oil and gas operating companies.

Safety during pigging relies on strict adherence to safety procedures, which give detailed description of a safe valve operating sequence. By physically blocking incorrect operations, valve interlocks enforce such sequences. Valve interlocks are permanently mounted to both manual and motor operated valves and the closure door. The interlocks block operation of a valve or door, unless the appropriate keys are inserted.

The principle of valve interlocking is the transfer of keys. Each lock is equipped with two keys: a key for the locked open position and one for the locked closed position. During an operating procedure, only one key at a time is free. This key only fits in the interlock belonging to the valve that is to be operated next in the operating procedure. All keys are uniquely coded to avoid the possibility that valves can be unlocked at an inappropriate time.

Nowadays intelligent interlocking solutions enable the integration of field devices like pressure or H2S meters in a valve interlocking sequence. This increases safety by integrating operator procedures with DCS and SIS safety systems.

Types of pigs

Gauging, separation and cleaning pigs

A "pig" is a tool that is sent down a pipeline and propelled by the pressure of the product flow in the pipeline itself. There are four main uses for pigs:

- Physical separation between different fluids flowing through the pipeline

- Internal cleaning of pipelines

- Inspection of the condition of pipeline walls (also known as an inline inspection (ILI) tool)

- Capturing and recording geometric information relating to pipelines (e.g., size, position).

One of the most common and versatile is the foam pig which is cut or poured out of open cell polyurethane foam into the shape of a bullet and is driven through pipelines for many reasons such as to prove the inner diameter of, clean, de-water, or dry out the line. There are several types of pigs for cleaning in various densities, from 32 to 160 kilograms per cubic metre (2 to 10 lb/cu ft) of foam, and in special applications up to 320 kg/m (20 lb/cu ft). Some have tungsten studs or abrasive wire mesh on the outside to abrade rust, scale, or paraffin wax deposits from the inside of the pipe. Other types are fully or criss-cross coated in urethane, or there are bare polyurethane foam pigs with a urethane coating just on the rear to seal and assist in driving the pig. There are also fully molded urethane pigs used for liquid removal, or batching several different products in one line.

Inline inspection pigs use various methods for inspecting a pipeline. A sizing pig uses one (or more) notched round metal plates as gauges. The notches allow different parts of the plate to bend when a bore restriction is encountered. More complex systems exist for inspecting various aspects of the pipeline.

Intelligent pig

Intelligent pigs are used to inspect the pipeline with sensors and record the data for later analysis. These pigs use technologies such as magnetic flux leakage (MFL) and ultrasound to inspect the pipeline. Intelligent pigs may also use calipers to measure the inside geometry of the pipeline.

In 1961, the first intelligent pig was run by Shell Development. It demonstrated that a self-contained electronic instrument could traverse a pipeline while measuring and recording wall thickness. The instrument used electromagnetic fields to sense wall integrity. In 1964 Tuboscope ran the first commercial instrument. It used MFL technology to inspect the bottom portion of the pipeline. The system used a black box similar to those used on aircraft to record the information; it was basically a highly customized analog tape recorder. Until recently, tape recording (although digital) was still the preferred recording medium. As the capacity and reliability of solid-state memory improved, most recording media moved away from tape to solid-state.

Capacitive sensor probes are used to detect defects in polyethylene gas pipeline. These probes are attached to the pig before it is sent through the polyethylene pipe to detect any defects in the outside of the pipe wall. This is done by using a triple-plate capacitive sensor in which electrostatic waves are propagated outward through the pipe's wall. Any change in dielectric material results in a change in capacitance. Testing was conducted by NETL DOE research lab at the Battelle West Jefferson's Pipeline Simulation Facility (PSF) near Columbus, Ohio.

Modern, intelligent or "smart" pigs are highly sophisticated instruments that include electronics and sensors to collect various forms of data during their trip through the pipeline. They vary in technology and complexity depending on the intended use and the manufacturer.

The electronics are sealed against leakage of the pipeline product, since these can range from being highly basic to highly acidic, and can be of extremely high pressure and temperature. Many pigs use specific materials according to the product in the pipeline. Power for the electronics is typically provided by onboard batteries which are also sealed. Data recording may be by various means ranging from analog tape, digital tape, or solid-state memory in more modern units.

The technology used varies by the service required and the design of the pig; each pigging service provider may have unique and proprietary technologies to accomplish the service. Surface pitting and corrosion, as well as cracks and weld defects in steel/ferrous pipelines are often detected using magnetic flux leakage (MFL) pigs. Other "smart" pigs use electromagnetic acoustic transducers to detect pipe defects. Caliper pigs can measure the roundness of the pipeline to determine areas of crushing or other deformations. Some smart pigs use a combination of technologies, such as providing MFL and caliper functions in a single tool. Trials of pigs using acoustic resonance technology have been reported.

During the pigging run the pig is unable to directly communicate with the outside world due to the distance underground or underwater and/or the materials that the pipe is made of. For example, steel pipelines effectively prevent any significant radio communications outside the pipe. It is therefore necessary that the pig use internal means to record its own movement during the trip. This may be done by odometers, gyroscope-assisted tilt sensors and other technologies. The pig records this positional data so that the distance it moves along with any bends can be interpreted later to determine the exact path taken.

Location verification

Location verification is often accomplished by surface instruments that record the pig's passage by either audible, magnetic, radio-transmission or other means. The sensors record when they detect the passage of the pig (time-of-arrival); this is then compared to the internal record for verification or adjustment. The external sensors may have Global Positioning System capability to assist in their location. A few pig passage indicators transmit the pig's passage, time and location, via satellite uplink. The pig itself cannot use GPS as the metal pipe blocks satellite signals.

After the pigging run has been completed, the positional data from the external sensors is combined with the pipeline evaluation data (corrosion, cracks, etc.) from the pig to provide a location-specific defect map and characterization. In other words, the combined data reveals to the operator the location, type and size of each pipe defect. This information is used to judge the severity of the defect and help repair crews locate and repair the defect quickly without having to dig up excessive amounts of pipeline. By evaluating the rate of change of a particular defect over several years, proactive plans can be made to repair the pipeline before any leakage or environmental damage occurs.

The inspection results are typically archived (perhaps in Pipeline Open Data Standard format) for comparison with the results of later pigging runs on the same pipeline.

In popular culture

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A pig has been used as a plot device in three James Bond films: Diamonds Are Forever, where Bond disabled a pig to escape from a pipeline; The Living Daylights, where a pig was modified to secretly transport a person through the Iron Curtain; and The World Is Not Enough, where a pig was used to carry and detonate a nuclear weapon in a pipeline.

A pig was also used as a plot device in the Tony Hillerman book The Sinister Pig where an abandoned pipeline from Mexico to the United States was used with a pig to transport illegal drugs.

A pig launcher was featured in the season 2 episode "Pipeline Fever" of the animated show Archer, wherein Sterling Archer and Lana Kane are tasked with going into a swamp and defending a pig launcher from radical environmentalist Joshua Gray.

See also

- Guided wave testing – Method of testing engineering structures, for nondestructive testing of a pipeline

- Hydraulically activated pipeline pigging

- Ice pigging – Pipe cleaning method, a method of pipe cleaning using ice slurry instead of a solid pig

- Pipeline transport – Pumping fluids or gas through pipesPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Pipeline video inspection

- Robotic non-destructive testing – Method of inspection using remotely operated tools

References

- "How It Works: Pipeline Pigging". www.products.slb.com. Schlumberger. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Pipeline Inspection Gauge ( PIG )". engineeredpower.com. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Abdel-Hafez, Mamoun; Chowdhury, Sheruzzaman (2015). "Pipeline Inspection Gauge Position Estimation Using Inertial Measurement Unit, Odometer, and a Set of Reference Stations". ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part B: Mechanical Engineering. 2 (2). doi:10.1115/1.4030945.

- "'Pigs' play crucial role in pipeline maintenance". Creamer Media Engineering News. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "How Does Pipeline Pigging Work?". rigzone.com. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "That's Some Smart Pig in the Pipeline". NPR.org. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "How Does Pipeline Pigging Work?". RIGGZONE.com. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- "Reaching 100 years in the pipeline". Pipelines International. August 6, 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-14. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- Miscellaneous Fabricated Supports Piping Technology & Products, (retrieved May 2012)

- "SERVINOX pig speed regulation unit". servinox.com. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- Shipp, Brett. "Pipeline 'pig' crashes through Grand Prairie home". WFAA. Archived from the original on 2012-08-29.

- "I.S.T. Molchtechnik GmbH". Piggingsystems.com. Archived from the original on 2010-04-13. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- Adapted from Amoco P&ID of pig launcher and Operating Manual 1988

- "NTS".

- "Process interlocking". Netherlocks. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "The integration of electronic components into mechanical valve interlocking solutions". Netherlocks. 2013-11-25. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "ProQuest Document View - Capacitive sensor technology for polyethylene pipe fault detection". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- "Oil and Natural Gas Research" (PDF). netl.doe.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- Stéphane Sainson, Inspection en ligne des pipelines. Principes et méthodes. Ed. Lavoisier. 2007. ISBN 978-2743009724. 332 p.

- "New techonology revolutionises gas pipeline checks". www.gassco.no. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "PIG Signaller". Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- "Enduro Pipeline Services | Engineered to Deliver Superior Results". www.enduropls.com. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "Pig Passage Indicator" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-11. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

External links

- Pipeline Pigging at VP Engineers

- Cup Pig / Batching Pig at VP Engineers

- Poly Pig at VP Engineers

- Magnetic Flux Leakage information

- Inline Inspection Association

- Inline Inspection and Pipeline Pigging Resource Archived 2014-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Oil-Pipeline Cracks Evading Robotic 'Smart Pigs'; Probes used by Exxon and other companies aren't spotting flaws that cause massive spills August 16, 2013 Wall Street Journal