| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Pier Paolo Vergerio" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

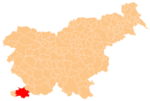

Pier Paolo Vergerio (c. 1498 – 4 October 1565), the Younger, was an Italian papal nuncio and later Protestant reformer.

Life

He was born at Capodistria (Koper), Istria, then part of the Venetian Republic and studied jurisprudence in Padua, where he delivered lectures in 1522. He also practiced law in Verona, Padua, and Venice. In 1526, he married Diana Contarini, whose early death was at least a partial cause of his entering an ecclesiastical career.

Papal nuncio

His advancement was so rapid that as early as 1533 he was papal nuncio to King Ferdinand in Germany, and he was there again in 1535 on business connected with the council. The nuncio's eagerness in the cause of the council brought him into a personal encounter with Martin Luther at Wittenberg.

Although Vergerio achieved little in the way of his appointed task, which was to induce the Protestants to send delegates to the council, Pope Paul III twice dispatched him across the Alps; and meanwhile rewarded him, first with the bishopric of Modruš in Croatia, and in the year 1536 with the bishopric of Capodistria. In the year 1540, Vergerio again entered active diplomatic service; he was at Worms at the religious conference as commissioner for King Francis I of France. It was in memory of the council that he dedicated the tract De unitate et pace ecclesiae. Like Cardinal Contarini, beside whom he also appeared at the religious conference of Regensburg in 1541, he was charged with having conceded too much to the Protestants. He then resolved to return to Capodistria and pursue thorough studies.

Vergerio had yet no thought of withdrawing from the Catholic Church, nor did he overstep the line of reformatory attempts within that Church, such as were espoused by Contarini and others. But suspicion was awakened such that on 13 December 1544, a denunciation of Vergerio was lodged with the Venetian Inquisition. Although, after due examination, Vergerio was released, Cardinal Marcello Cervini, later Pope Marcellus II, took advantage of the fact that Vergerio was not yet formally absolved to prevent his participation in the council for which he had laboured so many years.

Vergerio had to return from Riva and began a publishing activity which turned more and more against the Catholic Church. In connection with the death of Francesco Spiera and Vergerio's summary of the circumstances of 7 December 1548, Vergerio directed a sharp reply to the bishop of Padua.

Exile

Instead of responding to a second summons by the Nuncio Della Casa to appear before the tribunal in Venice, on 1 May 1549, he left Italy forever. The experiences at Spiera's sick-bed had brought Vergerio to a decision. The twelve treatises which he produced at Basel in 1550 supply information regarding his position. Meanwhile, the second trial had been conducted in Venice in absentia and was confirmed in Rome, 3 July 1549. Vergerio was convicted of heresy in 34 points, deposed from his episcopal dignity, and made subject to arrest.

At that time, however, he was in the Swiss Grisons and became active in a brisk round of polemics. His themes were the papacy, its origin and policy; the jubilees; saint and relic veneration, and the like. Vergerio continued in the Grisons till 1553 when he heeded a call from Duke Christopher of Württemberg to write and travel on behalf of Evangelical doctrine.

Although at first opposed to Primož Trubar, the consolidator of Slovene as a language, he later supported him and was his mentor for some time. He also contributed to the development of Croatian literature. In 1554 and 1555 he talked Trubar to start the translation of the Bible into Slovene. This resulted in Trubar's translation of the Gospel of Matthew in 1555, which was the first integral translation of a part of the Bible to this language, and later led to Trubar translating the entire New Testament into Slovene. A bust by Oreste Dequel was put on display in 1954 at Vergerio Square (Vergerijev trg) in Koper, the main coastal port town of Slovenia.

While Vergerio never again set foot in Italy, in 1556 he made his way to Poland, and conferred with Duke Albrecht of Prussia. He was in Poland in 1559 with the two-fold object of meeting the moves of the Nuncio Alois Lipomano, and of working counter to Johannes a Lasco. He sought permission to take part in the religious conference at Poissy in 1560, but he was not allowed to appear at the Council of Trent as the duke's delegate. During all these years he continued his polemical authorship and worked toward the publication of his Opera, though only the first volume appeared (1563). He died in Tübingen.

See also

- Girolamo Muzio, wrote a polemical treatise against Vergerio

References

- ^ Jacobson Schutte, Anne (1969). Pier Paolo Vergerio: The Making of an Italian Reformer. Librairie Droz. ISBN 9782600030724.

- ^ Filipović, Ivan (2009). "Vergerius Peter Pavel ml.". In Vide Ogrin, Petra (ed.). Slovenski biografski leksikon (in Slovenian). ISBN 978-961-268-001-5.

Further reading

- Robert A. Pierce, Pier Paolo Vergerio the Propagandist (Editore di Storia e Letteratura, 2003).