A Persian carpet (Persian: فرش ایرانی, romanized: farš-e irâni [ˈfærʃe ʔiː.ɹɒː.níː]), Persian rug (Persian: قالی ایرانی, romanized: qâli-ye irâni [ɢɒːˈliːje ʔiː.ɹɒː.níː]), or Iranian carpet is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in Iran (historically known as Persia), for home use, local sale, and export. Carpet weaving is an essential part of Persian culture and Iranian art. Within the group of Oriental rugs produced by the countries of the "rug belt", the Persian carpet stands out by the variety and elaborateness of its manifold designs.

Persian rugs and carpets of various types were woven in parallel by nomadic tribes in village and town workshops, and by royal court manufactories alike. As such, they represent miscellaneous, simultaneous lines of tradition, and reflect the history of Iran, Persian culture, and its various peoples. The carpets woven in the Safavid court manufactories of Isfahan during the sixteenth century are famous for their elaborate colours and artistic design, and are treasured in museums and private collections all over the world today. Their patterns and designs have set an artistic tradition for court manufactories which was kept alive during the entire duration of the Persian Empire up to the last royal dynasty of Iran.

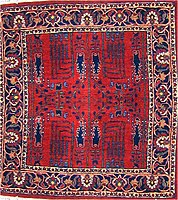

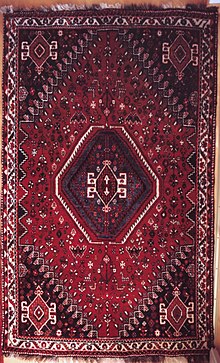

Carpets woven in towns and regional centers like Tabriz, Kerman, Ravar, Neyshabour, Mashhad, Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are characterized by their specific weaving techniques and use of high-quality materials, colours and patterns. Town manufactories like those of Tabriz have played an important historical role in reviving the tradition of carpet weaving after periods of decline. Rugs woven by the villagers and various tribes of Iran are distinguished by their fine wool, bright and elaborate colours, and specific, traditional patterns. Nomadic and small village weavers often produce rugs with bolder and sometimes more coarse designs, which are considered as the most authentic and traditional rugs of Persia, as opposed to the artistic, pre-planned designs of the larger workplaces. Gabbeh rugs are the best-known type of carpet from this line of tradition.

As a result of political unrest or commercial pressure, carpet weaving has gone through periods of decline throughout the decades. It particularly suffered from the introduction of synthetic dyes during the second half of the nineteenth century. Carpet weaving still plays a critical role in the economy of modern Iran. Modern production is characterized by the revival of traditional dyeing with natural dyes, the reintroduction of traditional tribal patterns, but also by the invention of modern and innovative designs, woven in the centuries-old technique. Hand-woven Persian rugs and carpets have been regarded as objects of high artistic and utilitarian value and prestige since the first time they were mentioned by ancient Greek writers.

Although the term "Persian carpet" most often refers to pile-woven textiles, flat-woven carpets and rugs like Kilim, Soumak, and embroidered tissues like Suzani are part of the rich and manifold tradition of Persian carpet weaving.

In 2010, the "traditional skills of carpet weaving" in Fars province and Kashan were inscribed to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

History

The beginning of carpet weaving remains unknown, as carpets are subject to use, deterioration, and destruction by insects and rodents. Woven rugs probably developed from earlier floor coverings, made of felt, or a technique known as "flat weaving". Flat-woven rugs are made by tightly interweaving the warp and weft strands of the weave to produce a flat surface with no pile. The technique of weaving carpets further developed into a technique known as loop weaving. Loop weaving is done by pulling the weft strings over a gauge rod, creating loops of thread facing the weaver. The rod is then either removed, leaving the loops closed, or the loops are cut over the protecting rod, resulting in a rug very similar to a genuine pile rug. Hand-woven pile rugs are produced by knotting strings of thread individually into the warps, cutting the thread after each single knot.

Pazyryk carpet

The Pazyryk carpet was excavated in 1949 from the grave of a Scythian nobleman in the Pazyryk Valley of the Altai Mountains in Siberia. Radiocarbon testing indicated that the Pazyryk carpet was woven in the 5th century BC. This carpet is 183 by 200 centimetres (72 by 79 inches) and has 36 symmetrical knots per cm (232 per inch). The advanced technique used in the Pazyryk carpet indicates a long history of evolution and experience in weaving. It is considered the oldest known carpet in the world. Its central field is a deep red colour and it has two animal frieze borders proceeding in opposite directions accompanied by guard stripes. The inner main border depicts a procession of deer, the outer men on horses, and men leading horses. The horse saddlecloths are woven in different designs. The inner field contains 4 × 6 identical square frames arranged in rows on a red ground, each filled by identical, star-shaped ornaments made up by centrally overlapping x- and cross-shaped patterns. The design of the carpet already shows the basic arrangement of what was to become the standard oriental carpet design: a field with repeating patterns, framed by a main border in elaborate design, and several secondary borders.

The discoverer of the Pazyryk carpet, Sergei Rudenko, assumed it to be a product of the contemporary Achaemenids. Whether it was produced in the region where it was found, or is a product of Achaemenid manufacture, remains subject to debate. Its fine weaving and elaborate pictorial design hint at an advanced state of the art of carpet weaving at the time of its production.

Early fragments

There are documentary records of carpets being used by the ancient Greeks. Homer, assumed to have lived around 850 BC, writes in Ilias XVII,350 that the body of Patroklos is covered with a "splendid carpet". In Odyssey Book VII and X "carpets" are mentioned. Pliny the Elder wrote (nat. VIII, 48) that carpets ("polymita") were invented in Alexandria. It is unknown whether these were flat-weaves or pile weaves, as no detailed technical information is provided in the Greek and Latin texts.

Flat-woven kilims dating to at least the fourth or fifth century AD were found in Turfan, Hotan prefecture, East Turkestan, China, an area which still produces carpets today. Rug fragments were also found in the Lop Nur area, and are woven in symmetrical knots, with 5–7 interwoven wefts after each row of knots, with a striped design, and various colours. They are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Other fragments woven in symmetrical as well as asymmetrical knots have been found in Dura-Europos in Syria, and from the At-Tar caves in Iraq, dated to the first centuries AD.

These rare findings demonstrate that all the skills and techniques of dyeing and carpet weaving were already known in western Asia before the first century AD.

Early history

Persian carpets were first mentioned around 400 BC, by the Greek author Xenophon in his book "Anabasis":

"αὖθις δὲ Τιμασίωνι τῷ Δαρδανεῖ προσελθών, ἐπεὶ ἤκουσεν αὐτῷ εἶναι καὶ ἐκπώματα καὶ τάπιδας βαρβαρικάς", (Xen. anab. VII.3.18)

- Next he went to Timasion the Dardanian, for he heard that he had some Persian drinking cups and carpets.

"καὶ Τιμασίων προπίνων ἐδωρήσατο φιάλην τε ἀργυρᾶν καὶ τάπιδα ἀξίαν δέκα μνῶν."

- Timasion also drank his health and presented him with a silver bowl and a carpet worth ten mines.

Xenophon describes Persian carpets as precious, and worthy to be used as diplomatic gifts. It is unknown if these carpets were pile-woven, or produced by another technique, e.g., flat-weaving or embroidery, but it is interesting that the very first reference to Persian carpets in the world literature already puts them into a context of luxury, prestige, and diplomacy.

There are no surviving Persian carpets from the reigns of the Achaemenian (553–330 BC), Seleucid (312–129 BC), and Parthian (ca. 170 BC – 226 AD) kings.

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire, which succeeded the Parthian Empire, was recognized as one of the leading powers of its time, alongside its neighbouring Byzantine Empire, for a period of more than 400 years. The Sasanids established their empire roughly within the borders set by the Achaemenids, with the capital at Ctesiphon. This last Persian dynasty before the arrival of Islam adopted Zoroastrianism as the state religion.

When and how exactly the Persians started weaving pile carpets is currently unknown, but the knowledge of carpet weaving, and of suitable designs for floor coverings, was certainly available in the area covering Byzance, Anatolia, and Persia: Anatolia, located between Byzance and Persia, was ruled by the Roman Empire since 133 BCE. Geographically and politically, by changing alliances and warfare as well as by trade, Anatolia connected the East Roman with the Persian Empire. Artistically, both empires have developed similar styles and decorative vocabulary, as exemplified by mosaics and architecture of Roman Antioch. A Turkish carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck's "Paele Madonna" painting was traced back to late Roman origins and related to early Islamic floor mosaics found in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.

Flat weaving and embroidery were known during the Sasanian period. Elaborate Sasanian silk textiles were well preserved in European churches, where they were used as coverings for relics, and survived in church treasuries. More of these textiles were preserved in Tibetan monasteries, and were removed by monks fleeing to Nepal during the Chinese cultural revolution, or excavated from burial sites like Astana, on the Silk Road near Turfan. The high artistic level reached by Persian weavers is further exemplified by the report of the historian Al-Tabari about the Spring of Khosrow carpet, taken as booty by the Arabian conquerors of Ctesiphon in 637 AD. The description of the rug's design by al-Tabari makes it seem unlikely that the carpet was pile woven.

Fragments of pile rugs from findspots in north-eastern Afghanistan, reportedly originating from the province of Samangan, have been carbon-14 dated to a time span from the turn of the second century to the early Sasanian period. Among these fragments, some show depictions of animals, like various stags (sometimes arranged in a procession, recalling the design of the Pazyryk carpet) or a winged mythical creature. Wool is used for warp, weft, and pile, the yarn is crudely spun, and the fragments are woven with the asymmetric knot associated with Persian and far-eastern carpets. Every three to five rows, pieces of unspun wool, strips of cloth and leather are woven in. These fragments are now in the Al-Sabah Collection in the Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Kuwait.

The carpet fragments, although reliably dated to the early Sasanian time, do not seem to be related to the splendid court carpets described by the Arab conquerors. Their crude knots incorporating shag on the reverse hints at the need for increased insulation. With their coarsely finished animal and hunting depictions, these carpets were likely woven by nomadic people.

Advent of Islam and the Caliphates

The Muslim conquest of Persia led to the end of the Sasanian Empire in 651 and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. Persia became a part of the Islamic world, ruled by Muslim Caliphates.

Arabian geographers and historians visiting Persia provide, for the first time, references to the use of carpets on the floor. The unknown author of the Hudud al-'Alam states that rugs were woven in Fārs. 100 years later, Al-Muqaddasi refers to carpets in the Qaināt. Yaqut al-Hamawi tells us that carpets were woven in Azerbaijān in the thirteenth century. The great Arabian traveller Ibn Battuta mentions that a green rug was spread before him when he visited the winter quarter of the Bakhthiari atabeg in Idhej. These references indicate that carpet weaving in Persia under the Caliphate was a tribal or rural industry.

The rule of the Caliphs over Persia ended when the Abbasid Caliphate was overthrown in the Siege of Baghdad (1258) by the Mongol Empire under Hulagu Khan. The Abbasid line of rulers recentered themselves in the Mamluk capital of Cairo in 1261. Though lacking in political power, the dynasty continued to claim authority in religious matters until after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt (1517). Under the Mamluk dynasty in Cairo, large carpets known as "Mamluk carpets" were produced.

Seljuq invasion and Turko-Persian tradition

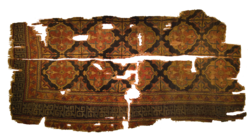

See also: Turkish carpetBeginning at latest with the Seljuq invasions of Anatolia and northwestern Persia, a distinct Turko-Persian tradition emerged. Fragments of woven carpets were found in the Alâeddin Mosque in the Turkish town of Konya and the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir, and were dated to the Anatolian Seljuq Period (1243–1302). More fragments were found in Fostat, today a suburb of the city of Cairo. These fragments at least give us an idea how Seljuq carpets may have looked. The Egyptian findings also provide evidence for export trade. If, and how, these carpets influenced Persian carpet weaving, remains unknown, as no distinct Persian carpets are known to exist from this period, or we are unable to identify them. It was assumed by Western scholars that the Seljuqs may have introduced at least new design traditions, if not the craft of pile weaving itself, to Persia, where skilled artisans and craftsmen might have integrated new ideas into their old traditions.

-

Carpet fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century.

Carpet fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century.

-

Seljuq carpet, 320 by 240 centimetres (126 by 94 inches), from the Alâeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century

Seljuq carpet, 320 by 240 centimetres (126 by 94 inches), from the Alâeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century

Mongol Ilkhanate and Timurid Empire

Between 1219 and 1221, Persia was raided by the Mongols. After 1260, the title "Ilkhan" was borne by the descendants of Hulagu Khan and later other Borjigin princes in Persia. At the end of the thirteenth century, Ghazan Khan built a new capital at Shãm, near Tabriz. He ordered the floors of his residence to be covered with carpets from Fārs.

With the death of Ilkhan Abu Said Bahatur in 1335, Mongol rule faltered and Persia fell into political anarchy. In 1381, Timur invaded Iran and became the founder of the Timurid Empire. His successors, the Timurids, maintained a hold on most of Iran until they had to submit to the "White Sheep" Turkmen confederation under Uzun Hassan in 1468; Uzun Hasan and his successors were the masters of Iran until the rise of the Safavids.

In 1463, the Venetian Senate, seeking allies in the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–1479) established diplomatic relations with Uzun Hassans court at Tabriz. In 1473, Giosafat Barbaro was sent to Tabriz. In his reports to the Senate of Venetia he mentions more than once the splendid carpets which he saw at the palace. Some of them, he wrote, were of silk.

In 1403–05 Ruy González de Clavijo was the ambassador of Henry III of Castile to the court of Timur, founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire. He described that in Timur's palace at Samarkand, "everywhere the floor was covered with carpets and reed mattings". Timurid period miniatures show carpets with geometrical designs, rows of octagons and stars, knot forms, and borders sometimes derived from kufic script. None of the carpets woven before 1500 AD have survived.

Safavid Period

In 1499, a new dynasty arose in Persia. Shah Ismail I, its founder, was related to Uzun Hassan. He is regarded as the first national sovereign of Persia since the Arab conquest, and established Shi'a Islam as the state religion of Persia. He and his successors, Shah Tahmasp I and Shah Abbas I became patrons of the Persian Safavid art. Court manufactories were probably established by Shah Tahmasp in Tabriz, but definitely by Shah Abbas when he moved his capital from Tabriz in northwestern to Isfahan in central Persia, in the wake of the Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–18). For the art of carpet weaving in Persia, this meant, as Edwards wrote: "that in a short time it rose from a cottage métier to the dignity of a fine art."

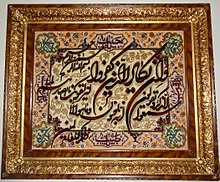

The time of the Safavid dynasty marks one of the greatest periods in Persian art, which includes carpet weaving. Later Safavid period carpets still exist, which belong to the finest and most elaborate weavings known today. The phenomenon that the first carpets physically known to us show such accomplished designs leads to the assumption that the art and craft of carpet weaving must already have existed for some time before the magnificent Safavid court carpets could have been woven. As no early Safavid period carpets survived, research has focused on Timurid period book illuminations and miniature paintings. These paintings depict colourful carpets with repeating designs of equal-scale geometric patterns, arranged in checkerboard-like designs, with "kufic" border ornaments derived from Islamic calligraphy. The designs are so similar to period Anatolian carpets, especially to "Holbein carpets" that a common source of the design cannot be excluded: Timurid designs may have survived in both the Persian and Anatolian carpets from the early Safavid, and Ottoman period.

"Design revolution"

By the late fifteenth century, the design of the carpets depicted in miniatures changed considerably. Large-format medallions appeared, ornaments began to show elaborate curvilinear designs. Large spirals and tendrils, floral ornaments, depictions of flowers and animals, were often mirrored along the long or short axis of the carpet to obtain harmony and rhythm. The earlier "kufic" border design was replaced by tendrils and arabesques. All these patterns required a more elaborate system of weaving, as compared to weaving straight, rectilinear lines. Likewise, they require artists to create the design, weavers to execute them on the loom, and an efficient way to communicate the artist's ideas to the weaver. Today this is achieved by a template, termed cartoon (Ford, 1981, p. 170). How Safavid manufacturers achieved this, technically, is currently unknown. The result of their work, however, was what Kurt Erdmann termed the "carpet design revolution".

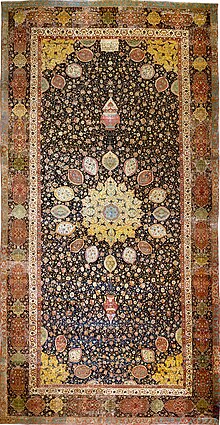

Apparently, the new designs were developed first by miniature painters, as they started to appear in book illuminations and on book covers as early as in the fifteenth century. This marks the first time when the "classical" design of Islamic rugs was established: The medallion and corner design (pers.: "Lechek Torūnj") was first seen on book covers. In 1522, Ismail I employed the miniature painter Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, a famous painter of the Garus school, as director of the royal atelier. Behzad had a decisive impact on the development of later Safavid art. The Safavid carpets known to us differ from the carpets as depicted in the miniature paintings, so the paintings cannot support any efforts to differentiate, classify and date period carpets. The same holds true for European paintings: Unlike Anatolian carpets, Persian carpets were not depicted in European paintings before the seventeenth century. As some carpets like the Ardabil carpets have inwoven inscriptions including dates, scientific efforts to categorize and date Safavid rugs start from them:

I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold.

There is no protection for my head other than this door.

The work of the slave of the threshold Maqsud of Kashan in the year 946.

— Inwoven inscription of the Ardabil carpet

The AH year of 946 corresponds to AD 1539–1540, which dates the Ardabil carpet to the reign of Shah Tahmasp, who donated the carpet to the shrine of Shaykh Safi-ad-din Ardabili in Ardabil, who is regarded as the spiritual father of the Safavid dynasty.

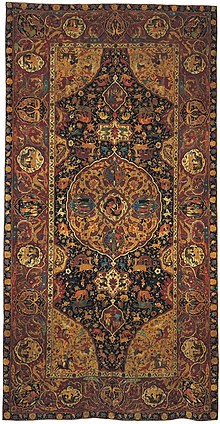

Another inscription can be seen on the "Hunting Carpet", now at the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan, which dates the carpet to 949 AH/AD 1542–3:

By the diligence of Ghyath ud-Din Jami was completed

This renowned work, that appeals to us by its beauty

In the year 949

— Inwoven inscription of the Milan Hunting carpet

The number of sources for more precise dating and the attribution of provenience increase during the 17th century. Safavid carpets were presented as diplomatic gifts to European cities and states, as diplomatic relations intensified. In 1603, Shah Abbas presented a carpet with inwoven gold and silver threads to the Venetian doge Marino Grimani. European noblemen began ordering carpets directly from the manufactures of Isfahan and Kashan, whose weavers were willing to weave specific designs, like European coats of arms, into the commissioned pieces. Their acquisition was sometimes meticulously documented: In 1601, the Armenian Sefer Muratowicz was sent to Kashan by the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa to commission 8 carpets with the Polish royal court of arms to be inwoven. The Kashan weavers did so, and on 12 September 1602 Muratowicz presented the carpets to the Polish king, and the bill to the treasurer of the crown. Representative Safavid carpets made of silk with inwoven gold and silver threads were erroneously believed by Western art historians to be of Polish manufacture. Although the error was corrected, carpets of this type retained the name of "Polish" or "Polonaise" carpets. The more appropriate type name of "Shah Abbas" carpets was suggested by Kurt Erdmann.

Masterpieces of Safavid carpet weaving

See also: Ardabil CarpetA. C. Edwards opens his book on Persian carpets with the description of eight masterpieces from this great period:

- Ardabil Carpet – Victoria and Albert Museum

- Hunting Carpet – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

- Chelsea Carpet – Victoria and Albert Museum

- Allover Animal and Floral Carpet – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

- Rose-ground Vase Carpet – Victoria and Albert Museum

- Medallion Animal and Floral Carpet with Inscription Guard – Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan

- Inscribed medallion Carpet with Animal and Flowers and Inscription Border – Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number: 32.16

- Medallion, Animal, and Tree Carpet – Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Safavid "Vase technique" carpets from Kirmān

A distinct group of Safavid carpets can be attributed to the region of Kirmān in southern Persia. May H. Beattie identified these carpets by their common structure: Seven different types of carpets were identified: Garden carpets (depicting formal gardens and water channels); carpets with centralized designs, characterized by a large medallion; multiple-medallion designs with offset medallions and compartment repeats; directional designs with the arrangements of little scenes used as individual motifs; sickle-leaf designs where long, curved, serrated and sometimes compound leaves dominate the field; arabesque; and lattice designs. Their distinctive structure consists of asymmetric knots; the cotton warps are depressed, and there are three wefts. Woolen wefts lie hidden in the center of the carpet, making up the first and third weft. Silk or cotton makes up the middle weft, which crosses from back to front. A characteristic "tram line" effect is evoked by the third weft when the carpet is worn.

The best known "vase technique" carpets from Kirmān are those of the so-called "Sanguszko group", named after the House of Sanguszko, whose collection has the most outstanding example. The medallion-and-corner design is similar to other 16th century Safavid carpets, but the colours and style of drawing are distinct. In the central medallion, pairs of human figures in smaller medallions surround a central animal combat scene. Other animal combats are depicted in the field, while horsemen are shown in the corner medallions. The main border also contains lobed medallions with Houris, animal combats, or confronting peacocks. In-between the border medallions, phoenixes and dragons are fighting. By similarity to mosaic tile spandrels in the Ganjali Khan Complex at the Kirmān bazaar with an inscription recording its date of completion as 1006 AH/AD 1596, they are dated to the end of the 16th or the beginning of the 17th century. Two other "vase technique" carpets have inscriptions with a date: One of them bears the date 1172 AH/AD 1758 and the name of the weaver: the Master Craftsman Muhammad Sharīf Kirmānī, the other has three inscriptions indicating that it was woven by the Master Craftsman Mu'min, son of Qutb al-Dīn Māhānī, between 1066 and 1067 AH/AD 1655–1656. Carpets in the Safavid tradition were still woven in Kirmān after the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1732 (Ferrier, 1989, p. 127).

The end of Shah Abbas II's reign in 1666 marked the beginning of the end of the Safavid dynasty. The declining country was repeatedly raided on its frontiers. Finally, a Ghilzai Pashtun chieftain named Mir Wais Khan began a rebellion in Kandahar and defeated the Safavid army under the Iranian Georgian governor over the region, Gurgin Khan. In 1722, Peter the Great launched the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many of Iran's Caucasian territories, including Derbent, Shaki, Baku, but also Gilan, Mazandaran and Astrabad. In 1722, an Afghan army led by Mir Mahmud Hotaki marched across eastern Iran, and besieged and took Isfahan. Mahmud proclaimed himself 'Shah' of Persia. Meanwhile, Persia's imperial rivals, the Ottomans and the Russians, took advantage of the chaos in the country to seize more territory for themselves. With these events, the Safavid dynasty had come to an end.

Persian carpets from the Safavid Era

-

Zayn al-'Abidin bin ar-Rahman al-Jami – Early 16th century miniature, Walters Art Museum

Zayn al-'Abidin bin ar-Rahman al-Jami – Early 16th century miniature, Walters Art Museum

-

Ardabil Carpet at the LACMA

Ardabil Carpet at the LACMA

-

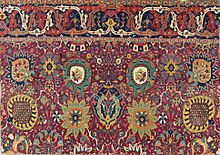

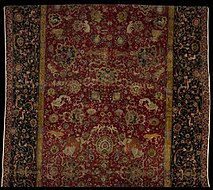

The Emperor's Carpet (detail), second half of the 16th century, Iran. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Emperor's Carpet (detail), second half of the 16th century, Iran. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Niche rug with the text of the Ayat al-Kursi, c. 1570s central Iran, Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Niche rug with the text of the Ayat al-Kursi, c. 1570s central Iran, Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

-

"Vase technique" carpet, Kirmān, 17th century

"Vase technique" carpet, Kirmān, 17th century

-

Safavid Persian carpet "Mantes carpet" at The Louvre

Safavid Persian carpet "Mantes carpet" at The Louvre

-

Detail of a Persian Animal carpet, Safavid period, Persia, 16th century, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

-

Detail of a Persian Animal carpet, Safavid period, Persia, 16th century: Lion and Qilin, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Detail of a Persian Animal carpet, Safavid period, Persia, 16th century: Lion and Qilin, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

Afsharid and Zand dynasties

Iran's territorial integrity was restored by a native Iranian Turkic Afshar warlord from Khorasan, Nader Shah. He defeated the Afghans, and Ottomans, reinstalled the Safavids on the throne, and negotiated Russian withdrawal from Irans Caucasian territories, by the Treaty of Resht and Treaty of Ganja. By 1736, Nader himself was crowned shah. There are no records of carpet weaving, which had sunk to an insignificant handicraft, during the Afsharid and Zand dynasties.

Qajãr dynasty

In 1789, Mohammad Khan Qajar was crowned king of Persia, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, which provided Persia with a long period of order and comparative peace, and the industry had an opportunity of revival. The three important Qajãr monarchs Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, and Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar revived the ancient traditions of the Persian monarchy. The weavers of Tabriz took the opportunity, and around 1885 became the founders of the modern industry of carpet weaving in Persia.

Pahlavi dynasty

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, Persia had become a battleground. In 1917, Britain used Iran as the springboard for an attack into Russia in an unsuccessful attempt to reverse the Revolution. The Soviet Union responded by annexing portions of northern Persia, creating the Persian Soviet Socialist Republic. By 1920, the Iranian government had lost virtually all power outside its capital: British and Soviet forces exercised control over most of the Iranian mainland. In 1925 Rezā Shāh, supported by the British government, deposed Ahmad Shah Qajar, the last Shah of the Qajar dynasty, and founded the Pahlavi dynasty. He established a constitutional monarchy that lasted until the Iranian revolution in 1979. Reza Shah introduced social, economic, and political reforms, ultimately laying the foundation of the modern Iranian state. To stabilize and legitimate their reign, Rezā Shāh and his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi aimed at reviving ancient Persian traditions. The revival of carpet weaving, often referring to traditional designs, was an important part of these efforts. In 1935, Rezā Shāh founded the Iran Carpet Company, and brought carpet weaving under government control. Elaborate carpets were woven for export, and as diplomatic gifts to other states.

The Pahlavi dynasty modernized and centralized the Iranian government, and sought effective control and authority over all their subjects. Reza Shah was the first Persian monarch to confront this challenge with modern weapons. Enforced by the army, nomadism was outlawed during the 1930s, traditional tribal dresses were banned, the use of tents and yurts was forbidden in Iran. Unable to migrate, having lost their herds, many nomadic families starved to death. A brief era of relative peace followed for the nomadic tribes in the 1940s and 1950s, when Persia was involved in the Second World War, and Rezā Shāh was forced to abdicate in 1941. His successor, Mohammed Reza Shah consolidated his power during the 1950s. His land reform program of 1962, part of the so-called White Revolution, despite obvious advantages for landless peasants, destroyed the traditional political organization of nomadic tribes like the Qashqai people, and the traditional way of nomadic life. The centuries-old traditions of nomadic carpet weaving, which had entered a process of decline with the introduction of synthetic dyes and commercial designs in the late nineteenth century, were almost annihilated by the politics of the last Iranian imperial dynasty.

-

Carpet in the Niavaran Palace, Tehran

Carpet in the Niavaran Palace, Tehran

-

Carpet in the Niavaran Palace, Tehran

Modern times

After the Iranian revolution, little information could at first be obtained about carpet weaving in Iran. In the 1970s and 1980s, a new interest arose in Europe in Gabbeh rugs, which were initially woven by nomadic tribes for their own use. Their coarse weaving and simple, abstract designs appealed to Western customers.

In 1992, the first Grand Persian Conference and Exhibition in Tehran presented for the first time modern Persian carpet designs. Persian master weavers like Razam Arabzadeh displayed carpets woven in the traditional technique, but with unusual, modern designs. As the Grand Conferences continue to take place at regular intervals, two trends can be observed in Iranian carpet weaving today. On the one hand, modern and innovative artistic designs are invented and developed by Iranian manufacturers, who thus take the ancient design tradition forward towards the twenty-first century. On the other hand, the renewed interest in natural dyes was taken up by commercial enterprises, which commission carpets to tribal village weavers. This provides a regular source of income for the carpet weavers. The companies usually provide the material and specify the designs, but the weavers are allowed some degree of creative freedom. With the end of the U.S. embargo on Iranian goods, also Persian carpets (including antique Persian carpets acquired at auctions) may become more easily available to U.S. customers again.

As commercial household goods, Persian carpets today are encountering competition from other countries with lower wages and cheaper methods of production: Machine-woven, tufted rugs, or rugs woven by hand, but with the faster and less costly loop weaving method, provide rugs in "oriental" designs of utilitarian, but no artistic value. Traditional hand woven carpets, made of sheep wool dyed with natural colours are increasingly sought after. They are usually sold at higher prices due to the large amount of manual work associated with their production, which has, essentially, not changed since ancient times, and due to the artistic value of their design. Thus, the Persian carpet retains its ancient status as an object of luxury, beauty, and art.

Materials

Wool

In most Persian rugs, the pile is of sheep's wool. Its characteristics and quality vary from each area to the next, depending on the breed of sheep, climatic conditions, pasturage, and the particular customs relating to when and how the wool is shorn and processed. Different areas of a sheep's fleece yield different qualities of wool, depending on the ratio between the thicker and stiffer sheep hair and the finer fibers of the wool. Usually, sheep are shorn in spring and fall. The spring shear produces wool of finer quality. The lowest grade of wool used in carpet weaving is "skin" wool, which is removed chemically from dead animal skin. Higher grades of Persian wool are often referred to as kurk, or kork wool, which is gained from the wool growing on the sheep's neck. Modern production also makes use of imported wool, e.g. Merino wool from New Zealand, because the high demand on carpet wool cannot be entirely met by the local production. Fibers from camels and goats are also used. Goat hair is mainly used for fastening the borders, or selvedges, of nomadic rugs like Balochi rugs, since it is more resistant to abrasion. Camel wool is occasionally used in Persian nomadic rugs. It is often dyed in black, or used in its natural colour. More often, wool said to be camel's wool turns out to be dyed sheep wool.

Cotton

Cotton forms the foundation of warps and wefts of the majority of modern rugs. Nomads who cannot afford to buy cotton on the market use wool for warps and wefts, which are also traditionally made of wool in areas where cotton was not a local product. Cotton can be spun more tightly than wool, and tolerates more tension, which makes cotton a superior material for the foundation of a rug. Especially larger carpets are more likely to lie flat on the floor, whereas wool tends to shrink unevenly, and carpets with a woolen foundation may buckle when wet. Chemically treated (mercerised) cotton has been used in rugs as a silk substitute since the late nineteenth century.

Silk

Silk is an expensive material, and has been used for representative carpets. Its tensile strength has been used in silk warps, but silk also appears in the carpet pile. Silk pile can be used to highlight special elements of the design. High-quality carpets from Kashan, Qum, Nain, and Isfahan have all-silk piles. Silk pile carpets are often exceptionally fine, with a short pile and an elaborate design. Silk pile is less resistant to mechanical stress, thus, all-silk piles are often used as wall hangings, or pillows.

Spinning

See also: Hand spinning and Spinning (textiles)

The fibers of wool, cotton, and silk are spun either by hand or mechanically by using spinning wheels or industrial spinning machines to produce the yarn. The direction in which the yarn is spun is called twist. Yarns are characterized as S-twist or Z-twist according to the direction of spinning. Two or more spun yarns may be twisted together or plied to form a thicker yarn. Generally, handspun single plies are spun with a Z-twist, and plying is done with an S-twist. Like nearly all Islamic rugs with the exception of Mamluk carpets, nearly all Persian rugs use "Z" (anti-clockwise) spun and "S" (clockwise)-plied wool.

Dyeing

The dyeing process involves the preparation of the yarn to make it susceptible for the proper dyes by immersion in a mordant. Dyestuffs are then added to the yarn which remains in the dyeing solution for a defined time. The dyed yarn is then left to dry, exposed to air and sunlight. Some colours, especially dark brown, require iron mordants, which can damage or fade the fabric. This often results in faster pile wear in areas dyed in dark brown colours, and may create a relief effect in antique oriental carpets.

Plants

Traditional dyes used in Persian rugs are obtained from plants and insects. In 1856, the English chemist William Henry Perkin invented the first aniline dye, mauveine. A variety of other synthetic dyes were invented thereafter. Cheap, readily prepared and easy to use as they were compared to natural dyes, their use is documented since the mid-1860s. The tradition of natural dyeing was revived in Turkey in the early 1980s. Chemical analyses led to the identification of natural dyes from antique wool samples, and dyeing recipes and processes were experimentally re-created.

According to these analyses, natural dyes used for carpet wool include:

- Red from Madder (Rubia tinctorum) roots

- Yellow from plants, including onion (Allium cepa), several chamomile species (Anthemis, Matricaria chamomilla), and Euphorbia

- Black: oak apples, oak acorns, tanner's sumach

- Green by double dyeing with indigo and yellow dye

- Orange by double dyeing with madder red and yellow dye

- Blue: indigo gained from Indigofera tinctoria

Some of the dyestuffs like indigo or madder were goods of trade, and thus commonly available. Yellow or brown dyestuffs more substantially vary from region to region. Many plants provide yellow dyes, like Vine weld, or Dyer's weed (Reseda luteola), Yellow larkspur, or Dyer's sumach (Cotinus coggygria). Grape leaves and pomegranate rinds, as well as other plants, provide different shades of yellow.

In Iran, traditional dyeing with natural dyes was revived in the 1990s, inspired by the renewed general interest in traditionally produced rugs, but master dyers like Abbas Sayahi had kept alive the knowledge about the traditional recipes.

Insect reds

Carmine dyes are obtained from resinous secretions of scale insects such as the Cochineal scale Coccus cacti, and certain Porphyrophora species (Armenian and Polish cochineal). Cochineal dye, the so-called "laq" was formerly exported from India, and later on from Mexico and the Canary Islands. Insect dyes were more frequently used in areas where Madder (Rubia tinctorum) was not grown, like west and north-west Persia.

Synthetic dyes

With modern synthetic dyes, nearly every colour and shade can be obtained so that without chemical analysis it is nearly impossible to identify, in a finished carpet, whether natural or artificial dyes were used. Modern carpets can be woven with carefully selected synthetic colours, and provide artistic and utilitarian value.

Abrash

The appearance of slight deviations within the same colour is called abrash (from Turkish abraş, literally, "speckled, piebald"). Abrash is seen in traditionally dyed oriental rugs. Its occurrence suggests that a single weaver has likely woven the carpet, who did not have enough time or resources to prepare a sufficient quantity of dyed yarn to complete the rug. Only small batches of wool were dyed from time to time. When one string of wool was used up, the weaver continued with the newly dyed batch. Because the exact hue of colour is rarely met again when a new batch is dyed, the colour of the pile changes when a new row of knots is woven in. As such, the colour variation suggests a village or tribal woven rug, and is appreciated as a sign of quality and authenticity. Abrash can also be introduced on purpose into a newly planned carpet design.

-

Madder (Rubia tinctorum) plant

Madder (Rubia tinctorum) plant

-

Indigo, historical dye collection of the Dresden University of Technology, Germany

Indigo, historical dye collection of the Dresden University of Technology, Germany

-

Kermez (Coccus cacti) lice

-

Section (central medallion) of a South Persian rug, probably Qashqai, late 19th century, showing irregular blue colours (abrash)

Techniques and structures

See also: Oriental rug § manufactureProcess of weaving a rug

The weaving of pile rugs is a time-consuming process which, depending on the quality and size of the rug, may take anywhere from a few months to several years to complete.

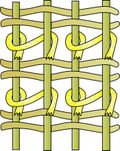

To begin making a rug, one needs a foundation consisting of warps and wefts: Warps are strong, thick threads of cotton, wool or silk which run through the length of the rug. Similar threads which pass under and over the warps from one side to the other are called wefts. The warps on either side of the rug are normally plied into one or more strings of varying thickness that are overcast to form the selvedge.

Weaving normally begins from the bottom of the loom, by passing a number of wefts through the warps to form a base to start from. Knots of dyed wool, cotton or silk threads are then tied in rows around consecutive sets of adjacent warps. As more rows are tied to the foundation, these knots become the pile of the rug. Between each row of knots, one or more shots of weft are passed to keep the knots fixed. The wefts are then beaten down by a comb-like instrument, the comb beater, to further compact and secure the newly woven row. Depending on the fineness of the weave, the quality of the materials and the expertise of the weavers, the knot count of a handmade rug can vary anywhere from 16 to 800 knots per square inch.

When the rug is completed, the warp ends form the fringes that may be weft-faced, braided, tasseled, or secured in other ways.

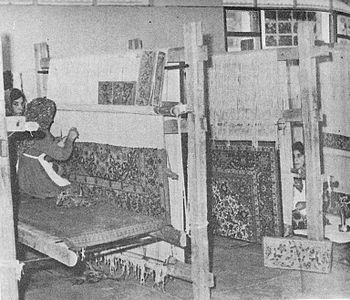

Looms

Looms, while sharing fundamental design principles, exhibit a diverse range of sizes and levels of complexity. The core technical requirements of a loom are to maintain proper tension and to divide the warp threads into alternating sets or "leaves." The inclusion of a shedding device enables the weaver to efficiently pass the weft threads through the crossed and uncrossed warp threads, eliminating the need for the painstaking process of manually weaving the weft in and out of the warp.

Horizontal looms

The simplest form of loom is a horizontal; one that can be staked to the ground or supported by sidepieces on the ground. The necessary tension can be obtained through the use of wedges. This style of loom is ideal for nomadic people as it can be assembled or dismantled and is easily transportable. Rugs produced on horizontal looms are generally fairly small and the weave quality is inferior to those rugs made on a professional standing loom. Urbanites are unlikely to use horizontal looms as they take up a lot of floor space, and professionals are unlikely to use them as they are unergonomic. Their cheapness and portability is less valuable to urban professionals.

Vertical looms

The technically more advanced, stationary vertical looms are used in villages and town manufactures. The more advanced types of vertical looms are more comfortable, as they allow for the weavers to retain their position throughout the entire weaving process. The Tabriz type of vertical loom allows for weaving of carpets up to double the length of the loom, while there is no limit to the length of the carpet that can be woven on a vertical roller beam loom. In essence, the width of the carpet is limited by the length of the loom beams.

There are three general types of vertical looms, all of which can be modified in a number of ways:

-

Tabriz loom

-

Tabriz looms in a carpet-making school in Iran in 1975. One weaver sits on the floor, two on a bench.

Tabriz looms in a carpet-making school in Iran in 1975. One weaver sits on the floor, two on a bench.

- The fixed village loom (dar sabet) is used mainly in Iran and consists of a fixed upper beam and a moveable lower or cloth beam which slots into two sidepieces. The correct tension of the warps is obtained by driving wedges into the slots. The weavers work on an adjustable plank which is raised as the work progresses.

- The Tabriz loom (dar Tabriz), named after the city of Tabriz, is used in Northwestern Iran. The warps are continuous and pass around behind the loom. Warp tension is obtained with wedges. The weavers sit on a fixed seat and when a portion of the carpet has been completed, the tension is released and the carpet is pulled down and rolled around the back of the loom. This process continues until the rug is completed, when the warps are severed and the carpet is taken off the loom.

- The roller beam loom (dar gardan, "roller loom") is used in larger Turkish manufactures, but is also found in Persia and India. It consists of two movable beams to which the warps are attached. Both beams are fitted with ratchets or similar locking devices. Once a section of the carpet is completed, is rolled on to the lower beam. On a roller beam loom, any length of carpet can be produced. In some areas of Turkey several rugs are woven in series on the same warps, and separated from each other by cutting the warps after the weaving is finished.

The Iranian names for the parts of the loom are:

- sardar, the upper beam (horizontal, equivalent to the warp beam)

- zirdar, the lower beam (horizontal, equivalent to the breast beam, especially when the fell is wrapped around it )

- rasto, the right post (upright); sometimes used for both posts

- chapro, the right post (upright)

- kaju of koji

- huf or haf

- goveh, the wedges regulating the height of the zirdar to tension the warp.

- takhteh alvar, weaver's bench, which may be adjustable in height.

A horizontal loom also has four pegs to hold it in the ground.

Tools

The weaver needs a number of essential tools: a knife for cutting the yarn as the knots are tied; a heavy comb-like instrument with a handle for packing down the wefts; and a pair of shears for trimming the pile after a row of knots, or a small number of rows, have been woven. In Tabriz the knife is combined with a hook to tie the knots, which speeds up work. A small steel comb is sometimes used to comb out the yarn after each row of knots is completed.

A variety of additional instruments are used for packing the weft. Some weaving areas in Iran known for producing very fine pieces use additional tools. In Kerman, a saber-like instrument is used horizontally inside the shed. In Bijar, a nail-like tool is inserted between the warps, and beaten on to compact the fabric even more. Bijar is also famous for their wet loom technique, which consists of wetting the warp, weft, and yarn with water throughout the weaving process to compact the wool and allow for a particularly heavy compression of the pile, warps, and wefts. When the rug is complete and dried, the wool and cotton expand, which results in a very heavy and stiff texture. Bijar rugs are not easily pliable without damaging the fabric.

A number of different tools may be used to shear the wool depending on how the rug is trimmed as the weaving progresses or when the rug is complete. Often in Chinese rugs the yarn is trimmed after completion and the trimming is slanted where the colour changes, giving an embossed three-dimensional effect.

Knots

Main article: Knotted-pile carpet Ghiordes knot

Ghiordes knot Senneh knot

Senneh knot

Persian carpets are mainly woven with two different knots: The symmetrical Turkish or "Giordes" knot, also used in Turkey, the Caucasus, East Turkmenistan, and some Turkish and Kurdish areas of Iran, and the asymmetrical Persian, or Senneh knot, also used in India, Turkey, Pakistan, China, and Egypt. The term "Senneh knot" is somewhat misleading, as rugs are woven with symmetric knots in the town of Senneh.

To tie a symmetric knot, the yarn is passed between two adjacent warps, brought back under one, wrapped around both forming a collar, then pulled through the center so that both ends emerge between the warps.

The asymmetric knot is tied by wrapping the yarn around only one warp, then the thread is passed behind the adjacent warp so that it divides the two ends of the yarn. The Persian knot may open on the left or the right.

The asymmetric knot allows to produce more fluent, often curvilinear designs, while more bold, rectilinear designs may use the symmetric knot. As exemplified by Senneh rugs with their elaborate designs woven with symmetric knots, the quality of the design depends more on the weaver's skills, than on the type of knot which is used.

Another knot frequently used in Persian carpets is the jufti knot, which is tied around four warps instead of two. A serviceable carpet can be made with jufti knots, and jufti knots are sometimes used in large single-colour areas of a rug, for example in the field, to save on material. However, as carpets woven wholly or partly with the jufti knot need only half the amount of pile yarn compared to traditionally woven carpets, their pile is less resistant to wear, and these rugs do not last as long.

-

Turkish (symmetric) knot

Turkish (symmetric) knot

-

Persian (asymmetric) knot, open to the right

Persian (asymmetric) knot, open to the right

-

Variants of the "Jufti" knot woven around four warps

Variants of the "Jufti" knot woven around four warps

-

Weaving with one warp depressed

Weaving with one warp depressed

-

Knitting an asymmetric knot, open to the right, with a knitting hook similar to the Tabriz type

Knitting an asymmetric knot, open to the right, with a knitting hook similar to the Tabriz type

-

Kilim end and fringes

Kilim end and fringes

Flat-woven carpets

Flat-woven carpets are given their colour and pattern from the weft which is tightly intertwined with the warp. Rather than an actual pile, the foundation of these rugs gives them their design. The weft is woven between the warp until a new colour is needed, it is then looped back and knotted before a new colour is implemented.

The most popular of flat-weaves is called the Kilim. Kilim rugs (along with jewellery, clothing and animals) are important for the identity and wealth of nomadic tribespeople. In their traditional setting Kilims are used as floor and wall coverings, horse-saddles, storage bags, bedding and cushion covers.

Various forms of flat-weaves exist including:

Design

Formats and special types

- Ghali (Persian: قالی, lit. "carpet"): large format carpets (190 × 280 cm).

- Dozar or Sedjadeh: The term comes from Persian do, "two" and zar, a Persian measure corresponding to about 105 centimetres (41 inches). Carpets of Dozar size are approximately 130–140 cm (51–55 in) x 200–210 cm (79–83 in).

- Ghalitcheh (Persian: قالیچه): Carpet of Dozar format, but woven in very fine quality.

- Kelleghi or Kelley : A long format, ca. 150–200 cm (59–79 in) x 300–600 cm (120–240 in). This format is traditionally placed at the head of a ghali carpet (kalleh means "head" in Persian).

- Kenareh : Smaller long format: 80–120 cm (31–47 in) × 250–600 cm (98–236 in). Traditionally laid out along the longer sides of a larger carpet (kenār means "side" in Persian language).

- Zaronim : corresponds to 1 ½ zar. These smaller rugs are about 150 cm (59 in) long.

Nomadic carpets are also known as Gelim (گلیم; including زیلو Zilou, meaning "rough carpet". In this use, Gelim includes both pile rugs and flat weaves (such as kilim and soumak).

Field design, medallions and borders

Rug design can be described by the way the ornaments are arranged within the pile. One basic design may dominate the entire field, or the surface may be covered by a pattern of repeating figures.

In areas with traditional, time-honoured local designs, such as the Persian nomad tribes, the weaver is able to work from memory, as the specific patterns are part of the family or tribal tradition. This is usually sufficient for less elaborate, mostly rectilinear designs. For more elaborate, especially curvilinear designs, the patterns are carefully drawn to scale in the proper colours on graph paper. The resulting design plan is termed a "cartoon". The weaver weaves a knot for each square on the scale paper, which allows for an accurate rendition of even the most complex designs. Designs have changed little through centuries of weaving. Today computers are used in the production of scale drawings for the weavers.

The surface of the rug is arranged and organized in typical ways, which in all their variety are nevertheless recognizable as Persian: One single, basic design may cover the entire field ("all-over design"). When the end of the field is reached, patterns may be cut off intentionally, thus creating the impression that they continue beyond the borders of the rug. This feature is characteristic for Islamic design: In the Islamic tradition, depicting animals or humans is prohibited even in a profane context, as Islam does not distinguish between religious and profane life. Since the codification of the Quran by Uthman Ibn Affan in 651 AD/19 AH and the Umayyad Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan reforms, Islamic art has focused on writing and ornament. The main fields of Persian rugs are frequently filled with redundant, interwoven ornaments, often in form of elaborate spirals and tendrils in a manner called infinite repeat.

Design elements may also be arranged more elaborately. One typical oriental rug design uses a medallion, a symmetrical pattern occupying the center of the field. Parts of the medallion, or similar, corresponding designs, are repeated at the four corners of the field. The common Persian "Lechek Torūnj" (medallion and corner) design was developed in Persia for book covers and ornamental book illuminations in the fifteenth century. In the sixteenth century, it was integrated into carpet designs. More than one medallion may be used, and these may be arranged at intervals over the field in different sizes and shapes. The field of a rug may also be broken up into different rectangular, square, diamond or lozenge shaped compartments, which in turn can be arranged in rows, or diagonally.

In contrast to Anatolian rugs, the Persian carpet medallion represents the primary pattern, and the infinite repeat of the field appears subordinate, creating an impression of the medallion "floating" on the field.

In most Persian rugs, the field of the rug is surrounded by stripes, or borders. These may number from one up to over ten, but usually there is one wider main border surrounded by minor, or guardian borders. The main border is often filled with complex and elaborate rectilinear or curvilinear designs. The minor border stripes show simpler designs like meandering vines. The traditional Persian border arrangement was highly conserved through time, but can also be modified to the effect that the field encroaches on the main border. This feature is often seen in Kerman rugs from the late nineteenth century, and was likely taken over from French Aubusson or Savonnerie weaving designs.

The corner articulations are a particularly challenging part of rug design. The ornaments have to be woven in a way that the pattern continues without interruption around the corners between horizontal and vertical borders. This requires advance planning either by a skilled weaver who is able to plan the design from start, or by a designer who composes a cartoon before the weaving begins. If the ornaments articulate correctly around the corners, the corners are termed to be "resolved", or "reconciled". In village or nomadic rugs, which are usually woven without a detailed advance plan, the corners of the borders are often not resolved. The weaver then discontinues the pattern at a certain stage, e.g., when the lower horizontal border is finished, and starts anew with the vertical borders. The analysis of the corner resolution helps distinguishing rural village, or nomadic, from workshop rugs.

-

Basic design elements of an Oriental carpet

Basic design elements of an Oriental carpet

-

Book binding from Collected Works (Kulliyat), 10th century AH/AD 16th, Walters Art Museum

Book binding from Collected Works (Kulliyat), 10th century AH/AD 16th, Walters Art Museum

-

Serapi carpet, Heriz region, Northwest Persia, circa 1875, with predominantly rectilinear design

Serapi carpet, Heriz region, Northwest Persia, circa 1875, with predominantly rectilinear design

-

Corner articulations in Oriental rugs

Corner articulations in Oriental rugs

Smaller and composite design elements

The field, or sections of it, can also be covered with smaller design elements. The overall impression may be homogeneous, although the design of the elements themselves can be highly complicated. Among the repeating figures, the boteh is used throughout the "carpet belt". Boteh can be depicted in curvilinear or rectilinear style. The most elaborate boteh are found in rugs woven around Kerman. Rugs from Seraband, Hamadan, and Fars sometimes show the boteh in an all-over pattern. Other design elements include ancient motifs like the Tree of life, or floral and geometric elements like, e.g., stars or palmettes.

Single design elements can also be arranged in groups, forming a more complex pattern:

- The Garus pattern consists of a lozenge with floral figure at the corners surrounded by lancet-shaped leaves sometimes called "fish". Garus patterns are used throughout the "carpet belt"; typically, they are found in the fields of Bidjar rugs.

- The Mina Khani pattern is made up of flowers arranged in a rows, interlinked by diamond (often curved) or circular lines. frequently all over the field. The Mina Khani design is often seen on Varamin rugs.

- The Shah Abbasi design is composed of a group of palmettes. Shah Abbasi motifs are frequently seen in Aran va bidgol, Kashan, Isfahan, Mashhad and Nain rugs.

- The Bid Majnūn, or Weeping Willow design is in fact a combination of weeping willow, cypress, poplar and fruit trees in rectilinear form. Its origin was attributed to Kurdish tribes, as the earliest known examples are from the Bidjar area.

- The Harshang or Crab design takes its name from its principal motive, which is a large oval motive suggesting a crab. The pattern is found all over the rug belt, but bear some resemblance to palmettes from the Safavid period, and the "claws" of the crab may be conventionalized arabesques in rectilinear style. This design was first used in the Khorasan district in Persia, and in origin ultimately derives from the Isfahan 'in and out' palmette design.

- The Gol Henai small repeating pattern is named after the Henna plant, which it does not much resemble. The plant looks more like the Garden balsam, and in the Western literature is sometimes compared to the blossom of the Horse chestnut.

Common motifs in Persian carpets

-

Boteh motif

Boteh motif

-

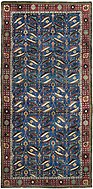

Bidjar rug with Garus pattern

Bidjar rug with Garus pattern

-

Pictorial carpet with Tree of life, birds, plants, flowers and vase motifs

-

Safavid period carpet (detail): Shah Abbasi motif

Safavid period carpet (detail): Shah Abbasi motif

-

Karaja carpet with Bid Majnūn, or "weeping willow" design

Karaja carpet with Bid Majnūn, or "weeping willow" design

-

Northwest Persia, 18th century carpet with Harshang or crab design

-

Bijar Rug with Bid Majnūn, or "weeping willow" design

Bijar Rug with Bid Majnūn, or "weeping willow" design

-

A carpet from Varamin with the Mina Khani motif

A carpet from Varamin with the Mina Khani motif

-

Pictorial carpet: Quran verses are woven into a Persian carpet

Pictorial carpet: Quran verses are woven into a Persian carpet

Classification

Persian carpets are best classified by the social context of their weavers. Carpets were produced simultaneously by nomadic tribes, in villages, town and court manufactures, for home use, local sale, or export.

Nomadic/tribal carpets

Nomadic, or tribal carpets are produced by different ethnic groups with distinct histories and traditions. As the nomadic tribes originally wove carpets mainly for their own use, their designs have maintained much of the tribal traditions. However, during the twentieth century, the nomadic lifestyle was changed to a more sedentary way either voluntarily, or by the forced settlement policy of the last Persian emperors of the Pahlavi dynasty. By 1970, it was observed that traditional weaving had almost ceased among major nomadic tribes, but in recent years, the tradition has been revived.

| Kurds | Bakhtiari & Luri | Chahar Mahal | Qashqai & Khamseh | Afshari | Beluch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knots | symmetric | symmetric | symmetric | symmetric and asymmetric, open to the left | symmetric and asymmetric, open to the right | mainly asymmetric open left, few open right or symmetric |

| Warps and wefts | Wool, sometimes cotton. Warps white or brown, wefts brown or red | Wool, goat hair, cotton. Warps brown or white, wefts brown or red. | Cotton, wefts sometimes blue | Wool, warps white (Q.) or white and brown (Kh.), wefts natural colours or red (Q.), or red and brown (Kh.) | Wool, warps white and brown, wefts orange red or pink | Warps white, wfts dark brown, later cotton |

| Selvages | overcast and reinforced | dark brown or goat hair, reinforced | reinforced, black wool | reinforced, two colours (Q.), overcast and reinforced, natural or dyed wool (Kh.) | reinforced with dyed wool | overcast in brown wool or goat hair |

| Ends | Kilim, 2 cm (0.79 in) to very long | Kilim, 2–8 cm (0.79–3.15 in), natural colours or stripes | Kilim, 2–5 cm (0.79–1.97 in) | Kilim, 2–5 cm (0.79–1.97 in), interlaced or brocaded | Kilim, 2–15 cm (0.79–5.91 in), natural colours or dyed stripes | 2–25 cm (0.79–9.84 in), coloured stripes and brocaded |

| Predominant colours | yellow, natural or corrosive brown | dark blue, bright red, strong yellow | dark blue, bright red, strong yellow | bright, shining red, different hues of blue, scarcely yellow, green | red changing into yellow, salmon red | bright blue |

Kurds

The Kurds are an ethnic group, mostly inhabiting the area spanning adjacent parts of southeastern (Turkey), western (Iran), northern (Iraq), and northern (Syria). The large population and the wide geographical distribution of the Kurds account for a varied production spanning a spectre from coarse and naïve nomadic weavings to the most elaborate town manufacture carpets, finely woven like Senneh, or heavy fabrics like Bijar carpets. Although Kurdish rugs represent a traditional part of Persian rug production, they merit separate consideration.

Senneh carpets

The city of Sanandij, formerly known as Senneh, is the capital of Iran's Kurdistan province. The rugs produced here are still known, also in the Iran of today, under their trade name "Senneh". They belong to the most finely woven Persian rugs, with knot counts up to 400 per square inch (6200/ dm). The pile is closely clipped, and the foundation is cotton, also silk was used in antique carpets. Some fine carpets have silk warps dyed in different colours which create fringes in different colours known as "rainbow warps" in the rug trade. Mostly blue colours are used in the field, or a pale red. The predominant pattern used to be the Garus pattern, with a lozenge-shaped central medallion also filled with repeating Garus patterns on a different background colour. More realistic floral patterns are also seen, probably in rugs woven for export to Europe.

Bijar carpets

The town of Bijar lies around 80 kilometres (50 miles) northeast of Sanadij. Together, these two towns and their surrounding areas have been major centers of rug production since the eighteenth century. Carpets woven in Bijar and the surrounding villages show more varied designs than Senneh rugs, which has led to the distinction between "city" and "village" Bijar rugs. Often referred to as "The Iron Rug of Persia", the Bijar rug is distinguished by its highly packed pile, which is produced by a special technique known as "wet weaving", with the help of a special tool. Warps, weft and pile are constantly kept wet during the weaving process. When the finished carpet is allowed to dry, the wool expands, and the fabric becomes more compact. The fabric is further compacted by vigorous hammering on nail-like metal devices which are inserted between the warps during the weaving. Alternate warps are moderately to deeply depressed. The fabric is further compacted by using wefts of different thickness. Usually one of three wefts is considerably thicker than the others. The knots are symmetrical, at a density of 60 to over 200 per square inch (930–2100/ dm), rarely even over 400 (6200/ dm).

The colours of Bijar rugs are exquisite, with light and dark blues, and saturated to light, pale madder red. The designs are traditionally Persian, with predominant Garus, but also Mina Khani, Harshang, and simple medallion forms. Frequently the design is more rectilinear, but Bijar rugs are more easily identified by their peculiar, stiff and heavy weaving than by any design. Bijar rugs cannot be folded without risking to damage the foundation. A specific feature is also the lack of outlining, particularly of the smaller patterns. Full-size "sampler" carpets showing only examples of field and border designs rather than a fully developed carpet design are called "vagireh" by rug traders, and are frequently seen in the Bijar area. New Bijar carpets are still exported from the area, mostly with less elaborate Garus designs and dyed with good synthetic dyes.

Kurdish village rugs

From a Western perspective, there is not much detailed information about Kurdish village rugs, probably because there is insufficient information to identify them, as they have never been specifically collected in the West. Usually, rugs can only be identified as "northwest Persian, probably Kurdish". As is generally the case with village and nomadic rugs, the foundation of village rugs is more predominantly of wool. Kurdish sheep wool is of high quality, and takes dyes well. Thus, a rug with the distinct features of "village production", made of high-quality wool with particularly fine colours may be attributed to Kurdish production, but mostly these attributions remain educated guesswork. Extensive use of common rug patterns and designs poses further difficulty in assigning a specific regional or tribal provenience. A tendency of integrating regional traditions of the surrounding areas, like Anatolian or northwestern Persian designs was observed, which sometimes show distinct, unusual design variations leading to suggest a Kurdish production from within the adjacent areas. Also, northwestern Persian towns like Hamadan, Zenjan or Sauj Bulagh may have used "Kurdish" design features in the past, but modern production on display at the Grand Persian Exhibitions seems to focus on different designs.

Qashqai

The early history of the Qashqai people remains obscure. They speak a Turkic dialect similar to that of Azerbaijan, and may have migrated to the Fars province from the north during the thirteenth century, possibly driven by the Mongol invasion. Karim Khan Zand appointed the chief of the Chahilu clan as the first Il-Khan of the Qashqai. The most important subtribes are the Qashguli, Shishbuluki, Darashuri, Farsimadan, and Amaleh. The Gallanzan, Rahimi, and Ikdir produce rugs of intermediate quality. The rugs woven by the Safi Khani and Bulli subtribes are considered among the highest quality rugs. The rugs are all wool, usually with ivory warps, which distinguishes Qashqai from Khamseh rugs. Qashqai rugs use asymmetric knots, while Gabbeh rugs woven by Qashqai more often use symmetric knots. Alternate warps are deeply depressed. Wefts are in natural colours or dyed red. The selvedges are overcast in wool of different colours, creating a "barber pole" pattern, and are sometimes adorned with woolen tassels. Both ends of the rug have narrow, striped flat-woven kilims. Workshops were established in the nineteenth century already around the town of Firuzabad. Rugs with repeating boteh and the Garus pattern, medallion, as well as prayer rug designs resembling the millefleurs patterns of Indian rugs were woven in these manufactures. The Garus design may sometimes appear to be disjointed and fragmented. The Qashqai are also known for their flat-weaves, and for their production of smaller, pile-woven saddle bags, flat-woven larger bags (mafrash), and their Gabbeh rugs.

The Shishbuluki (lit.: "six districts") rugs are distinguished by small, central, lozenge-shaped medallions surrounded by small figures aligned in concentric lozenges radiating from the center. The field is most often red, details are often woven in yellow or ivory. Darashuri rugs are similar to those of the Shishbuluki, but not so finely woven.

As the truly nomadic way of life has virtually come to an end during the twentieth century, most Qashqai rugs are now woven in villages, using vertical looms, cotton warps, or even an all-cotton foundation. They use a variety of designs associated with the Qashqai tradition, but it is rarely possible to attribute a specific rug to a specific tribal tradition. Many patterns, including the "Qashqai medallion" previously thought to represent genuine nomadic design traditions, have been shown to be of town manufacture origin, and were integrated into the rural village traditions by a process of stylization.

The revival of natural dyeing has had a major impact on Qashqai rug production. Initiated in Shiraz during the 1990s by master dyers as Abbas Sayahi, particularly Gabbeh rugs raised much interest when they were first presented at the Great Persian Exhibition in 1992. Initially woven for home use and local trade, coarsely knotted with symmetric knots, the colours initially seen were mostly natural shades of wool. With the revival of natural colours, Gabbeh from Fars province soon were produced in a full range of colours. They met the Western demand for primitive, naïve folk art as opposed to elaborate commercialized designs, and gained high popularity. In the commercial production of today, the Gabbeh rug patterns remain simple, but tend to show more modern types of design.

Khamseh federation

See also: Shiraz rug

The Khamseh (lit.: "five tribes") federation was established by the Persian Qajar government in the nineteenth century, to rival the dominant Qashqai power. Five tribal groups of Arab, Persian and Turkic origin were combined, including the Arab tribe, the Basseri, Baharlu, Ainalu, and Nafar tribes. It is difficult to attribute a specific rug to the Khamseh production, and the label "Khamseh" is often used as a term of convenience. Dark woolen warps and borders are associated with Arab Khamseh rugs, warps are rarely depressed, the colour scheme is more subdued. Specifically, a stylized bird ("murgh") pattern is often seen on rugs attributed to the confederation, arranged around a succession of small, lozenge shaped medallions. Basseri rugs are asymmetrically knotted, brighter in colours, with more open space and smaller ornaments and figure with Orange as the specific colour. The Baharlu are a Turkic-speaking tribe settled around Darab, and few carpets are known from this more agricultural region.

Luri

The Lurs live mainly in western and south-western Iran. They are of Indo-European origin. Their dialect is closely related to the Bakhtiari dialect and to the dialect of the southern Kurds. Their rugs have been marketed in Shiraz. The rugs have a dark wool foundation, with two wefts after each row of knots. Knots are symmetrical or asymmetrical. Small compartment designs of repeating stars are often seen, or lozenge-shaped medallions with anchor-like hooks on both ends.

Afshari

See also: Afshar rugsThe Afshar people are a semi-nomadic group of Turkic origin, principally located in the mountainous areas surrounding the modern city of Kerman in southeastern Iran. They produce mainly rugs in runner formats, and bags and other household items with rectilinear or curvilinear designs, showing both central medallions and allover patterns. Colours are bright and pale red. The flat-woven ends often show multiple narrow stripes.

Balochi

See also: Balochi rugThe Baloch people live in eastern Iran. They weave small-format rugs and a variety of bags with dark red and blue colours, often combined with dark brown and white. Camel hair is also used.

Village carpets

Carpets produced in villages are usually brought to a regional market center, and carry the name of the market center as a label. Sometimes, as in the case of the "Serapi" rug, the name of the village serves as a label for a special quality. Village carpets can be identified by their less elaborate, more highly stylized designs.

Criteria suggesting village production include:

- A rug of so-called scatter-size (dozar) that has been woven in a settled environment;

- woven without a cartoon;

- woven without reconciled corners;

- woven with possible idiosyncrasies of construction and pattern elements.

Village rugs are more apt to have warps of wool rather than of cotton. Their designs are not as elaborate and ornate than the curvilinear patterns of city rugs. They are more likely to display abrash and conspicuous mistakes in detail. On simple vertical looms, the correct tension of the warps is difficult to maintain during the entire weaving process. So, village rugs tend to vary in width from end to end, have irregular sides, and may not lay entirely flat. In contrast to manufactory rugs, there is considerable variety in treating the selvedges and fringes. Village rugs are less likely to present depressed warps, as compared to manufactory rugs. They tend to make less use of flat woven kilim ends to finish off the ends of the rug, as compared to tribal rugs. The variation in treatment of fringes and ends, and the way the selvedges are treated, provide clues as to place of origin.

Northwestern Iran

Main articles: Azerbaijani carpet, Ardabil rugs, and Caucasian carpets and rugsTabriz is the market center for the Iranian Northwest. Carpets woven in this region mainly use the symmetric knot. Heriz is a local center of production for mainly room-size carpets. Warps and weft are of cotton, the weaving is rather coarse, with high-quality wool. Prominent central medallions are frequently seen with rectilinear outlines highlighted in white. The ornaments of the field are in bold, rectilinear style, sometimes in an allover design. Higher quality Heriz carpets are known as Serapi. The village of Sarab produces runners and galleries with broad main borders either of camel hair or wool dyed in the colour of camel hair. Large, interconnected medallions fill the field. Mostly rectilinear, geometric and floral patterns are dyed in pink red and blue. Bakshaish carpets with a shield-shaped large medallion, less elaborate rectilinear patterns in salmon red and blue are labeled after the village of Bakhshayesh. Karadja produces runners with specific square and octagonal medallions in succession.

Western Iran

Major production centers in the West are Hamadan, Saruk with its neighbouring town of Arak, Minudasht also known under the trade name Lilihan and Serabend, Maslaghan, Malayer and Feraghan.

- Carpets from Maslaghan are usually small (120 × 180 cm), the warps are made of cotton, the wefts of wool or cotton. The large medallion shows a so-called "lobed Göl", the colours of which are in sharp contrast to the field, with small borders. Malayer, Sarouk and Feraghan are located closely to each other. They use cotton for the foundation.

- Malayer carpets are distinguished by their single-weft and the use of the symmetrical knot. Allover and medallion patterns are common, the boteh motif is frequently used.

- The original Sarouk design was distinguished by a round-star medallion with surrounding pendants. The traditional design of the Sarouk rug was modified by the weavers towards an allover design of detached floral motives, the carpets were then chemically washed to remove the unwanted colours, and the pile was painted over again with more desirable colours. Feraghan carpets are less finely woven than Sarouk. Often the Garus pattern is seen all over. medallions, if they occur, show more geometrical designs. A corroding green dye is typical for Feraghan carpets.

Southern Iran

Since the mid-twentieth century, commercial production started in the villages of Abadeh and Yalameh. Abadeh rugs adopted traditional Qashqai designs, but used cotton for warps and wefts, the latter often dyed in blue. Yalameh carpets more resemble Khamseh designs with hooked medallions arranged in the field. Warps and wefts were often in white.

Eastern Iran

The village of Doroksh is known for its carpet production in Eastern Persia. They are characterized by their use of orange dyes, the boteh motif is often seen. Usually, there is only one border. The knots are asymmetric.

Town carpets

Tabriz in the West, Kerman Ravar in the South, and Mashhad in the Northeast of Iran, together with the central Iranian towns Such as: Aran va bidgol, Kashan, Ravar, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are the main centers of town manufacture.

- Aran va bidgol has the best and most beautiful carpets and rugs in Iran. Its beauty, charm and softness have made this city the largest center of machine carpet production in Iran and the second largest manufacturer of machine carpet in the world.

- Tabriz has been a center of carpet production for centuries. Many designs are reproduced by Tabrizi weavers, with wool or silk in the pile, and wool, cotton or silk in the foundation.

- Kerman is known for finely knotted, elegant carpets with prominent cochineal red, ivory and golden yellow colours. Their medallions are elegantly designed, and elaborate versions of the boteh design are often seen in the field.