| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Menstrual cup" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A menstrual cup is a menstrual hygiene device which is inserted into the vagina during menstruation. Its purpose is to collect menstrual fluid (blood from the uterine lining mixed with other fluids). Menstrual cups are made of elastomers (silicone rubbers, latex rubbers, or thermoplastic rubbers). A properly fitting menstrual cup seals against the vaginal walls, so tilting and inverting the body will not cause it to leak. It is impermeable and collects menstrual fluid, unlike tampons and menstrual pads, which absorb it.

Menstrual cups come in two types. The older type is bell-shaped, often with a stem, and has walls more than 2mm thick. The second type has a springy rim, and attached to the rim, a bowl with thin, flexible walls. Bell-shaped cups sit over the cervix, like cervical caps, but they are generally larger than cervical caps and cannot be worn during vaginal sex. Ring-shaped cups sit in the same position as a contraceptive diaphragm; they do not block the vagina and can be worn during vaginal sex. Menstrual cups are not meant to prevent pregnancy.

Every 4–12 hours (depending on capacity and the amount of flow), the cup is emptied (usually removed, rinsed, and reinserted). After each period, the cup requires cleaning. One cup may be reusable for up to 10 years, making their long-term cost lower than that of disposable tampons or pads, though the initial cost is higher. As menstrual cups are reusable, they generate less solid waste than tampons and pads, both from the products themselves and from their packaging. Bell-shaped cups have to fit fairly precisely; it is common for users to get a perfect fit from the second cup they buy, by judging the misfit of the first cup. Ring-shaped cups are one-size-fits-most, but some manufacturers sell multiple sizes.

Reported leakage for menstrual cups is similar or rarer than for tampons and pads. It is possible to urinate, defecate, sleep, swim, do gymnastics, run, ride bicycles or riding animals, weightlift, and do heavy exercise while wearing a menstrual cup. Incorrect placement or cup size can cause leakage. Most users initially find menstrual cups difficult, uncomfortable, and even painful to insert and remove. This generally gets better within 3–4 months of use; having friends who successfully use menstrual cups helps, but there is a shortage of research on factors that ease the learning curve. Menstrual cups are a safe alternative to other menstrual products; risk of toxic shock syndrome infection is similar or lower with menstrual cups than for pads or tampons.

Terminology

The terminology used for menstrual cups is sometimes inconsistent. This article uses "menstrual cup" to mean all types, and for clarity, distinguishes the two main types as "bell-shaped" and "ring-shaped".

The thick-walled bell-shaped cups are the older type, and the term "menstrual cup" is sometimes used to refer only to bell-shaped cups. But in modern formal contexts, such as academic research and regulations, "menstrual cup" usually refers to both types.

The US Food and Drug Administration holds that "A menstrual cup is a receptacle placed in the vagina to collect menstrual flow." The EU legislated that "The product group ‘reusable menstrual cups’ shall comprise reusable flexible cups or barriers worn inside the body whose function is to retain and collect menstrual fluid, and which are made of silicone or other elastomers."

Ring-shaped cups are also called "menstrual discs" and sometimes "menstrual rings", to distinguish them from bell-shaped cups. Bell-shaped cups are sometimes called "menstrual bells".

Because bell-shaped cups are commonly depicted as being placed in the vaginal canal, well below the cervix, they are also called "vaginal cups", with the ring-shaped cups called "cervical cups". This may not clearly reflect their position in the body. MRI imaging suggests that, contrary to some manufacturer's depictions, the bell-shaped cups called "vaginal cups" are placed over the cervix, in a position similar to a cervical cap (not to be confused with a cervical cup). Ring-shaped cups, called "cervical cups", also cover the cervix, but have one edge next to the cervix, and the other located further down the vagina, so that the cup is nearly parallel to the long axis of the vagina.

In the 1800s, menstrual cups were called "'catamenial sacks", and were similar external catamenial sacks of "canoe-like form", which in turn were similar to catamenial sacks which were waterproof rubber undersheet supports for absorbent pads. These were made from india-rubber or gutta-percha, forms of latex.

Use

Menstrual cups are favoured by backpackers and other travellers, as they are easy to pack and only one is needed.

Thorough washing of the cup and hands helps to avoid introducing new bacteria into the vagina, which may heighten the risk of UTIs and other infections. Disposable and reusable pads do not demand the same hand hygiene, though reusable pads also require access to water for washing out pads.

If the hands have come into contact with any chemical that directly trigger sensory receptors in the skin, such as menthol or capsaicin, all traces of the chemical should be removed before touching the mucous membranes.

A UN spec recommends that cups should not be shared; they should only ever be used by one person.

Insertion

-

There are a variety of ways to fold a bell-shaped menstrual cup for insertion; punchdown fold, 7 fold, and C fold illustrated.

There are a variety of ways to fold a bell-shaped menstrual cup for insertion; punchdown fold, 7 fold, and C fold illustrated.

-

The folded menstrual cup is inserted and allowed to spring open.

The folded menstrual cup is inserted and allowed to spring open.

-

To ensure the menstrual cup is fully open and therefore creating a seal against the vaginal wall, users can run a finger around the cup to feel for bumps (a sign it is not open), or users can gently pinch and twist the menstrual cup.

To ensure the menstrual cup is fully open and therefore creating a seal against the vaginal wall, users can run a finger around the cup to feel for bumps (a sign it is not open), or users can gently pinch and twist the menstrual cup.

-

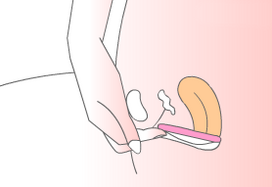

Inserting a thin-walled menstrual disc/ring-shaped cup. Pinching the sides of the cup together and positioning it for insertion.

Inserting a thin-walled menstrual disc/ring-shaped cup. Pinching the sides of the cup together and positioning it for insertion.

-

After the pinched cup is inserted, the outer edge of the cup is tucked behind the pubic bone, opening out the cup. The inner edge of the cup must cover the cervix.

After the pinched cup is inserted, the outer edge of the cup is tucked behind the pubic bone, opening out the cup. The inner edge of the cup must cover the cervix.

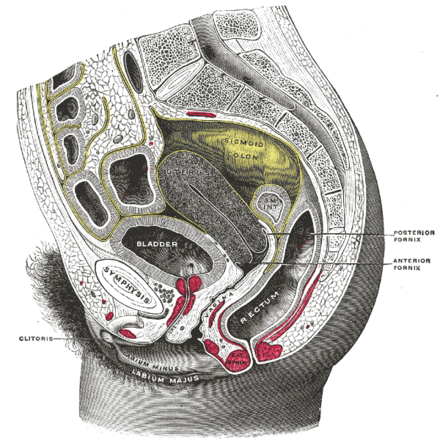

The vagina is narrowest at the entrance and becomes wider and easier to stretch further in. Menstrual cups are folded or compressed to insert them, and then opened out once inside. The innermost portion of the cup typically goes into the vaginal fornix (the groove around the cervix). Menstrual cups cannot pass through the cervix into the uterus.

The muscles of the pelvic floor, which surround the vaginal entrance, are relaxed to let the cup pass. Involuntarily tensing the vaginal muscles can make it impossible for anything to enter the vagina without causing pain. Many initially find insertion difficult, uncomfortable, and even painful, but learn to do it within a few cycles. There is little publicly available research on learning to use menstrual cups which compares types of cup or instructions.

A bell-shaped cup is folded or pinched before being inserted into the vagina. There are various folding techniques for insertion; common folds include the "C" fold, the "7" fold, and the punch-down fold. Once inside, the cup will normally unfold automatically and seal against the vaginal wall. In some cases, the user may need to twist the cup or flex the vaginal muscles to ensure the cup is fully open.

In practice, the rim of a bell-shaped cup generally sits in the vaginal fornix, the ring-shaped hollow around the cervix. Some fornixes are much deeper than others. Those with deeper fornixes may use insertion techniques such as inserting the cup partway, opening it before the rim passes the cervix, and then pushing it up into place; or they may press the cup to one side and let it open slowly, the rim slipping over the cervix. If correctly sized and inserted, the cup should not leak or cause any discomfort. The stem should be completely inside the vagina. If it can't be positioned inside, the cup can be removed and the stem trimmed.

Ring-shaped cups (also called menstrual discs or menstrual rings) are inserted differently than bell-shaped cups: by squeezing opposite sides of the rim together until they touch, sliding the inner end of the folded cup to the end of the vaginal canal, and tucking the outer end behind the pubic bone. They can be less bulky than a bell-shaped cup, no bulkier than a tampon. Inserting a ring-shaped cup requires more knowledge of anatomy, to get the cup under and around the cervix, not rucked up in front of it. Ring-shaped cups with non-circular rims are designed to be inserted with the widest, deepest part going in first. If they are inserted the wrong way around they may leak. If there are stems or other removal aids, they should be on the end inserted last.

If lubricant is used for insertion, it should be water-based, as silicone lubricant can be damaging to the silicone.

Wear

-

An X-ray that shows a bell-shaped menstrual cup in place. The cervix can be seen in the mouth of the cup; the cup rim is in the vaginal fornix. Bell-shaped cups have the same shape when in use inside the body as outside, and create an empty space (black on the X-ray).

An X-ray that shows a bell-shaped menstrual cup in place. The cervix can be seen in the mouth of the cup; the cup rim is in the vaginal fornix. Bell-shaped cups have the same shape when in use inside the body as outside, and create an empty space (black on the X-ray).

-

An MRI showing a bell-shaped menstrual cup in place; cup in blue, uterus in red. The ectocervix (the portion of the cervix that protrudes into the vagina) sits inside the cup. Sagittal plane.

An MRI showing a bell-shaped menstrual cup in place; cup in blue, uterus in red. The ectocervix (the portion of the cervix that protrudes into the vagina) sits inside the cup. Sagittal plane.

A bell-shaped cup may protrude far enough to be uncomfortable if it is too long. It may press too firmly against the bladder, causing discomfort, frequent urination, or difficulty urinating, if it is too firm, or the wrong shape. A bell-shaped cup may leak if it is not inserted correctly, and does not pop open completely and seal against the walls of the vagina. Some factors mentioned in association with leakage included menorrhagia, unusual anatomy of the uterus, need for a larger size of menstrual cup, and incorrect placement of the menstrual cup, or that it had filled to capacity. However, a proper seal may continue to contain fluid in the upper vagina even if the cup is full.

While many diagrams show bell-shaped menstrual cups very low in the vagina, with the vagina gaping open, in-vivo imaging shows that the cups sit high, with their rim around the cervix, and the vagina squishes shut below the cup, sealing it inside the body.

If a ring-shaped cup pops out at the outermost edge, either the innermost edge got caught on near side of the cervix rather than tucked into the fornix behind it, or it is too big, or the outermost edge hasn't been tucked behind the public bone firmly enough. In either any case it will leak. If it comes loose and starts to slide out when using the toilet, or leaks on exertion (when exercising, coughing, or sneezing), it is too large or too small. Some deliberately choose a ring-shaped cup which will leak when they deliberately bear down on it, but not at any other time.

Emptying

It is possible to deliberately empty a ring-shaped menstrual disc by muscular effort, without removing it (provided it is of a fairly soft material, and the right size). This is done in a suitable location, such as when sitting on a toilet. Bell-shaped cups must be removed to empty them.

The cup is emptied after 4–12 hours of use (or when it is full). Leaving the cup in for at least 3–4 hours allows the menstrual fluid to provide some lubrication.

If sewers are available, menstrual cups can be emptied into a flush toilet, or sink, bath, or shower drain, and the drain rinsed with water. They can also be emptied into a pit latrine.

When using a urine-diverting dry toilet, menstrual blood can be emptied into the part that receives the feces. If any menstrual blood falls into the funnel for urine, it can be rinsed away with water.

In the absence of other facilities, menstrual fluid can be emptied into a cathole. This is a single-use hole 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) deep, more than 200 feet (60 m) from water (and frequented areas like trails or campsites), ideally dug in organic soil, in an area where the waste will break down fast. Water used to rinse the cup can also be disposed of in the cathole, which is then refilled and concealed.

Removal

-

To remove a bell-shaped cup, the seal is broken by running a finger cup the side of the menstrual cup, or pinching the base of the vessel. The cup is then slowly and gently removed, shifting the menstrual cup from side to side.

To remove a bell-shaped cup, the seal is broken by running a finger cup the side of the menstrual cup, or pinching the base of the vessel. The cup is then slowly and gently removed, shifting the menstrual cup from side to side.

-

A filled menstrual cup after use. With practice, it is possible to remove a bell-shaped cup without spilling or bloodying the hands.

A filled menstrual cup after use. With practice, it is possible to remove a bell-shaped cup without spilling or bloodying the hands.

-

Hooking a finger under the rim of a ring-shaped cup to remove it; the finger can also be hooked over the rim, or the rim can be pinched.

Hooking a finger under the rim of a ring-shaped cup to remove it; the finger can also be hooked over the rim, or the rim can be pinched.

Many initially find removal difficult, uncomfortable, and even painful, but learn to do it without problems within a few cycles.

The muscles of the pelvic floor are kept relaxed, to allow the cup to pass out through them. Techniques like squatting, putting a leg up on the toilet seat, spreading the knees, and bearing down on the cup as if giving birth are sometimes used to make removal easier. Because vaginal tenting can make the cup harder to remove, some manufacturers recommend waiting at least an hour after sex before removal.

Slow removal and a firm grip avoid dropping the cup; experience, time and privacy also help. Dropping the cup can contaminate it (see cleaning, below). If a cup is removed or emptied over a pit latrine, it may fall in and be unretrievable.

A bell-shaped cup is removed by reaching up to its stem to find the base. Simply pulling on the stem does not break the seal, and yanking on it can cause pain. To release the seal, the base of the cup is pinched, or a finger is placed alongside the cup. The exception is two-part cups with separate stems; those can be pulled out to break the seal. The shape of the (one-part) stem thus has little effect on how easy the cup is to remove, and many people trim the stem right off for comfort. The cup is removed slowly; rocking or wriggling it gently may help. Some fold the cup in a "C" fold before removal, to break the seal and reduce the bulk; folding the cup inside the body is generally more difficult than folding it outside.

A cup can be removed over a toilet, bath, or shower to catch spills. Removal becomes less messy with practice, and it is possible to consistently remove bell-shaped cup without spilling, by keeping it upright. If it is necessary to track the amount of menses produced (e.g., for medical reasons), a bell-shaped cup allows one to do so accurately before emptying.

Ring-shaped menstrual cups are removed by hooking the rim with a finger (from either side), or by pinching it with multiple fingers and pulling. Some ring-shaped cups have a dimple in the bowl, to make it easier to hook the rim from below. Some also have stems, but contrary to bell-shaped cups, these stems attach to the rim of the cup, and can be pulled to break the seal. Others have pull loops that fold flat against the bowl, which can also be pulled to remove. Removing ring-shaped cups is typically done over a toilet in case of spilling; the softer bowl squishes flat during removal, making it very difficult not to spill any menstruum. Removal aids like pull loops can make ring-shaped cups easier to remove without spilling, but they still tend to be messier than bell-shaped cups.

Cleaning

There is little published or independent research on how to clean menstrual cups. Manufacturers generally provide cleaning instructions, but they differ widely. Manufacturers did not provide any evidence validating or giving a rationale for the various cleaning instructions, as of 2022. A UN specification says that "The cup must be washed frequently in clean, boiling water as per manufacturer's instructions."

In response to the 2022 review of manufacturer's recommendations (next section), which said there was no published evidence on how well cleaning methods work, a single small in-vitro study was done to compare cleaning methods.

Cleaning study

-

Rinsing a cup under cool, clean running water in a sink. Hot water speeds coagulation and can set bloodstains.

Rinsing a cup under cool, clean running water in a sink. Hot water speeds coagulation and can set bloodstains.

-

Soap is effective at cleaning the cup, but all soap residues must be rinsed off, so scented or moisturizing soaps are not recommended.

Soap is effective at cleaning the cup, but all soap residues must be rinsed off, so scented or moisturizing soaps are not recommended.

-

Pouring just-boiled water into a ceramic mug. Steeping menstrual cups is very effective.

Pouring just-boiled water into a ceramic mug. Steeping menstrual cups is very effective.

-

Raised text and other unsmooth features provide more purchase for bacteria.

Raised text and other unsmooth features provide more purchase for bacteria.

A single small in-vitro study (using human blood, but incubation outside the body) compared four cleaning treatments:

- cold water (cup rubbed with fingers under running water for 30 seconds)

- cold water and liquid soap (used instead of the more common bar soap so that the quantity could be more easily measured)

- cold water followed by steeping (putting the cup in a ceramic mug and pouring water over it as soon as the water boiled, then steeping for 5 min with the mug covered by a small plate; after five minutes, the water in the mug was still above 75 Celsius)

- cold water and soap followed by steeping

It did not compare boiling to steeping, or steeping after warming the mug. All of the methods decreased the bacterial load of the cups, with steeping having a bigger individual effect than soap; when using all three cleaning methods on cups (the fourth treatment), the authors were unable to culture bacteria from them. Just rinsing and steeping, with no soap, had very similar or identical effects.

The authors recommended using as many of the cleaning methods as possible, but using soap only if it can be thoroughly washed off, as soap residue can irritate the vagina. They pointed out the need for in-vivo studies, looking at real health outcomes, and the need for studies on more than the single model of cup they tested.

Review of manufacturers' recommendations

A 2022 review stated that "Publicly accessible evidence is needed to create consumer confidence in the recommended cleaning practices... nearly all menstrual cup manufacturers fail to provide any publicly available independent evidence that supports their recommended cleaning practices". The review found no standards or guidelines for menstrual cup cleaning practices, and urged independent research to establish a normative standard.

| Method | Before first use | Within cycle | Between cycles | Variations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| not cleaning it at all, just reinserting it as-is | has been suggested as a stopgap measure by at least one manufacturer. | |||

| rinsing it in water only | 10/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this, four of them as an alternative to using soap | rinsing in cold water at least initially to inhibit bloodstains; rinsing it in a sink, or using a water bottle, especially in areas with no running water. Some users carry a bottle of clean water to rinse the cup with when on the road. | ||

| washing it in mild soap and water | 17/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this 1/24 counterecommended soap, and 1/24 said soap was unnecessary. | 14/17 recommended unscented, oil-free, water-based, nonantibacterial soap. Some counterecommend castile soap, dish soap, and heavy-duty facial cleanser. The scent left by soap is a residue; moisturizing soaps also leave a residue. | ||

| washing it in a proprietary menstrual-cup-cleaning solution and water | 9/17 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this as an optional alternative to using soap. | |||

| wiping it off, with tissue or another dry wipe, and reinserting it | 8/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this. | if using toilet paper, blotting instead of rubbing to stop the paper from disintegrating. | ||

| wiping it with a disposable wipe | 1/24 manufacturers recommended wiping with a proprietary soap-based wipe in 2022. | 8/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended a proprietary wipe. | Some distributors market wipes intended specifically for cleaning menstrual cups; they may contain a variety of active ingredients, including purified water, soap, or denatured alcohol. Non-cup-specific wipes sometimes used include isopropyl alcohol disposable wipe (not the sort with a moisturizer, as that leaves a residue), or wipes such as "feminine wipes" or hypoallergenic baby wipes; some types of wipes have moisturizing lotions, preservatives, or other residues. 3/24 manufacturers counterrecommended cleaning cups with isopropyl alcohol in 2022; 1/24 counterecommended alcohol-based wipes. | |

| boiling the cup or steeping, covered, in freshly boiled water (like some types of tea) | In 2022, 18/24 manufacturers recommended this. 7/18 recommended five minutes or less, 7/18 recommended 5–10 minutes, one recommended 10-20 min, and 2/18 recommended over twenty minutes, with one last manufacturer not suggesting a time. | 3/24 manufacturers recommended this in 2022; all offered alternatives | 23/24 manufacturers recommended this or noted it as optional in 2022. 11/23 recommended five minutes or less, 5/23 recommended 5–10 minutes, and 2/23 recommended over twenty minutes, with 5/23 manufacturer not suggesting a time. | Almost all manufacturers recommend boiling before first use. Almost all manufacturers recommend boiling or steeping in boiling water between cycles, as mandatory or as an option, and most users do boil their cups. 2/24 recommended boiling times of no more than five minutes, and 1/24, <10min. Long boiling can damage the cup, and boiling it dry can melt it. Kitchen facilities may lack privacy. Distributors seldom provide a boiling pot; people unable to afford a cup-boiling container sometimes used containers which might leave a harmful residue, like old paint cans. |

| steaming the cup in a menstrual-cup steamer | 1/24 manufacturers recommended this in 2022. | 1/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this. | Takes 8–10 minutes. Steamer must be cleaned and dried afterwards, USB steamers are not affordable in many lower-and middle-income countries. | |

| microwaving | 1/24 recommended microwaving for five minute with water in a proprietary container | 9/24 manufacturers recommended this in 2022. | Some manufacturers recommend, others counterrecommend; one recommended microwaving for five minute with water in a proprietary container, others recommend boiling in water in a microwave. This is not workable in lower-income houses that do not have microwaves. Microwaving in a breast-pump sterilization bag is also sometimes practiced. | |

| washing in the dishwasher | 4/24 manufacturers counterrecommended cleaning cups in the dishwasher in 2022. | |||

| vinegar solution | 1/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended boiling in a 1:9 solution. | 1/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended soaking in vinegar. | 3/24 manufacturers counterrecommended cleaning cups with vinegar in 2022. | |

| soaking with a sterilizing tablet (generally sodium dichloroisocyanurate, used for baby bottles and breast pump equipment) | 4/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this. | 1/24 manufacturers recommended this in 2022. | 9/24 manufacturers recommended this in 2022. | |

| petroleum-based lubricants and essential oils | 6/24 manufacturers counterrecommended using essential oils with cups in 2022; 5/24 countereccomended petroleum lubricants. | |||

| "corrosive" or "harsh" cleaning chemicals | 6/24 manufacturers in 2022 counterreccomended this, but none of them were specific about what cleaners were to be avoided. | |||

| baking soda | 2/24 counterrecommended using baking soda in 2022; none recommended it. | |||

| soaking in hydrogen peroxide solution | Some manufacturers recommend, others (3/24) counterrecommended any sort of bleach in 2022. | |||

| soaking in isopropyl alcohol solution | In 2022, one manufacturer recommended soaking thus for 10 minutes. | 2/24 manufacturers in 2022 recommended this. | 3/24 manufacturers counterrecommended cleaning cups with isopropyl alcohol in 2022. | |

| ultraviolet light irradiation | Some manufacturers recommend. | |||

| ozone generation | Some manufacturers recommend. | |||

| a cup with a mechanically superhydrophobic surface | N/A | N/A | N/A | A "microtopographic design that incorporates micron-scale thick lubricant" (polydimethylsiloxane) in a "replenishing slippery surface"; the manufacturer says that week-old bloodstains can be wiped off, and that rinsing in water and wiping are the only cleaning needed. |

The most common recommendations are:

- boiling a new cup before using it for the first time, for about five minutes

- when a menstrual cup is removed and emptied, it is generally cleaned before it is reinserted; the most common recommendations were:

- washing with water and a "mild" soap, for preference

- rinsing in water (second choice)

- wiping with a clean, dry wipe such as toilet tissue (third choice)

- boiling or steeping a cup between menstrual cycles for about five minutes.

Most manufacturers recommended using water and soap if readily available. Many counterrecommend scented soaps and soaps made with an excess of oil or fat (in order to create moisturizing soap). Scents and moisturizers are designed to remain as residues on the hands after washing.

Some manufacturers sell and recommend proprietary cleaning products. These are not considered necessary.

Containers for steeping and boiling

-

Mugs may be used to steep menstrual cups.

Mugs may be used to steep menstrual cups.

-

The container is covered with a plate or lid (like the lid of this gaiwan) during steeping.

The container is covered with a plate or lid (like the lid of this gaiwan) during steeping.

-

Commercial canned food, in metal and glass cans. Both types of can have been used for sterilizing menstrual cups. Some containers are likely to be unsafe to use for this purpose.

Commercial canned food, in metal and glass cans. Both types of can have been used for sterilizing menstrual cups. Some containers are likely to be unsafe to use for this purpose.

-

Mason jars (without their lids) are also used to boil and steep cups.

Mason jars (without their lids) are also used to boil and steep cups.

A dedicated menstrual-cup-cleaning pot may be too expensive, and use of kitchen pots socially unacceptable. Alternatives like used paint cans may contain harmful substances. Food cans are used; these hold their temperature better than an unwarmed ceramic mug for steeping, but there is no data on the safety of tinned or plastic-coated food cans for this use. Mason jars made for home canning are heatproof and designed to be sterilized by boiling; they have been used to steep-sterilize menstrual cups. They have also been used (presumably unsealed) for storage. Mugs have also been used. USB-powered sterilizers and proprietary menstrual cup cleaning solutions are not accessible to poorer users.

Some menstrual cups come with cleaning containers; the cup is intended to be steeped in the container with boiling water for five minutes or microwaved in the container with water for 3–5 minutes. Containers are made from a medical-grade silicone or polypropylene.

In practice

A South African study found that 93% used tap water when cleaning their cups at home, but only 32-44% rinsed their cups with tap water outside the home; when water was not available, many women left their cups in all day.

In situations where clean water is hard to get or in short supply, it may be difficult to clean the cup with water. Reusable alternatives, like washing rags, may take more water. A lack of soap also presents a problem in some developing countries.

Washing a menstrual cup in a sink at a public toilet can pose problems, as the handwashing sinks are often in a public space rather than in the toilet cubicle. Accessible loos generally have sinks that can be reached from the toilet, but they may be needed by people with limited mobility. Some users do not empty cups in public toilets; if they only empty the cup twice a day, every 12 hours, they can wait until they return home.

Boiling menstrual cups once a month can also be a problem in developing countries, if there is a lack of water, firewood or other fuel.

Stain removal

Smooth-surfaced cups are easier to clean; moulded text, ridges, bumps, and holes make it a bit more difficult. Some suggest scrubbing out grooves with a toothbrush, rag, or cloth, and airholes with an interdental brush.

Stains on any color of the cup can be removed or at least lightened by soaking the cup in diluted hydrogen peroxide, or leaving it out in the sun for a few hours. Some cup makers recommend against the use of hydrogen peroxide.

Some menstrual cups are sold colorless and translucent, but several brands also offer colored cups. Translucent cups lose their initial appearance faster than colored – they tend to get yellowish stains with use. It can be harder to see whether a dark-coloured cup is clean. The shade of a colored cup may change over time, though stains are often not as obvious on colored cups.

Storage

Manufacturers typically suggest letting the cup dry out fully and storing it dry in a breathable container, such as the cloth bag usually provided with the cup. Airtight wraps and containers are counterrecommended, especially if the cup is at all damp.

Safety

Menstrual cups are a safe option for managing menstruation, with risks comparable to or lower than alternatives (with the possible exception of the risk of intrauterine device (IUD) displacement). They are safe in in low-, middle-, and high-income settings.

Using a menstrual cup does not harm the vaginal flora. Studies looked at disruptions of the vaginal flora including excessive growth of yeast, excessive growth of harmful bacteria, excessive growth of Staphylococcus aureus, and other microorganisms; subjects using menstrual cups were not more likely to have these common vaginal problems than subjects using other methods, (cloth or disposable pads, or tampons); in some studies, they were less likely.

Menstrual cups can be used with an IUD, but it isn't clear whether using a menstrual cup increases the risk of IUD expulsion, as of 2023. About 6% of all IUD users have an IUD come out unintentionally, most commonly during menstruation. In three studies of expulsion rates in menstrual cup users, the rates were 3.7%, 17.3% and 18.6%. Menstrual cup users differ demographically from the general population of IUD users (for instance, they tend to be younger, and youth independently increases the risk of losing an IUD unintentionally). It has been suggested that when removing a menstrual cup, the user might accidentally pull on the IUD string, or that the suction might pull the IUD out. There is no data on what removal techniques, brands or types of cup might be riskier. Some IUD users have had the strings of their IUD cut quite short as a precaution against accidentally pulling it out while removing a cup. So far there is no data on IUD displacement in people using ring-shaped cups, which do not suction to the cervix in the way bell-shaped cups can.

Rare issues

The number of menstrual cup users is unknown. This makes it hard to estimate the rate of rarer health problems related to cups. There are few reports, and rare problems are unlikely to turn up in a randomized study.

Serious difficulty removing the cup, requiring professional assistance, is rare but not unknown. A 2019 review found two cases with bell-shaped silicone cups, and one case with an elaborate older model of diaphragm-like cup called a Gynaeseal. There were also 46 reports with a single brand of disposable ring-shaped plastic cup (of about 100 million cups sold); most were reported to the manufacturer.

A 2019 review found three cases in which a malpositioned menstrual cup pressed on a ureter, which blocked the flow of urine from a kidney to the bladder; this caused renal colic (acute pain on the flank and lower back) which went away once the cup was removed. It also found one case of urinary incontinence while using the cup, which cleared up when the cup was removed, and five other urinary complaints.

Most menstrual cups are made of silicone, and silicone allergies are rare. In 2010, there was one report to the FDA of someone with a silicone allergy who had to have reconstructive surgery to the vagina after using a silicone menstrual cup. There were two reports to the FDA of allergic reactions to a disposable plastic cup. A 2017 study in Dharpur, Gujarat, using a silicone cup described as ring-shaped and depicted as bell-shaped, collected two reports of rashes and one report of an allergy.

The 2019 review also found two reports of irritation to the vagina and cervix, neither of which had clinical consequences, and two of severe pain (one on removing a cup for the first time). There were three reports of a vaginal wound from menstrual cup use, but reviewers were not able to review any associated medical records.

One case report noted the development of endometriosis and adenomyosis in one menstrual cup user. Endometriosis affects 10–15% of menstruators. An online survey on the topic, with nine respondents, found three people who had used a menstrual cup and developed endometriosis. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration made a public statement that there was insufficient evidence of risk.

Toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a potentially fatal bacterial illness. A 2019 review found the risk of toxic shock syndrome with menstrual cup use to be low, with five cases identified via their literature search (one with an IUD, one with an immunodeficiency). Data from the United States showed rates of TSS to be lower in people using menstrual cups versus high-absorbency tampons. Infection risk is similar or less with menstrual cups compared to pads or tampons.

There is an association between TSS and tampon use, although the exact connection remains unclear. TSS associated with menstrual cup use appears to be very rare, probably because menstrual cups are not absorbent, do not irritate the vaginal mucosal tissue, and so do not measurably change the vaginal flora.

The risk of TSS associated with contraceptive cervical caps and contraceptive diaphragms is also very low. Like menstrual cups, these products both use mostly medical grade silicone or latex.

A widely reported study showed that in vitro, bacteria associated with toxic shock syndrome (TSS) are capable of growing on menstrual cups, but results from similar studies are conflicting, and results from in-vivo studies do not show cause for concern.

Size, shape, and flexibility

There are no standards for the measurement or aize-labelling of menstrual cups, and each manufacturer uses their own system. Self-measurement of the vagina and third-party measurement tables are often used to get a good fit.

Capacity affects how often the cup must be emptied. Some prefer to empty the cup only twice a day, morning and evening, to avoid emptying it in public toilets. Flow rates vary. On average, about 30mL of menstrual fluid is lost per month; 10 to 35mL is normal. Menstrual blood loss of more than 80mL per month is considered heavy menstrual bleeding, and grounds for consulting a doctor.

The stated capacity of menstrual cup is generally measured ex vivo (outside the body). It is the volume of fluid that will fill the cup to just below the airholes, if there are airholes, or just below the rim, if there are none. These volume measurements are generally overestimates of real life capacity, because the cup may be compressed inside the body, and the cervix will often occupy some of the volume of the cup. Ex-vivo capacities for menstrual cups are in the range of tens of milliliters; for comparison, a normal-size tampon or pad holds about 5mL when thoroughly soaked.

Smooth cups with no sharp edges are recommended by the UN. Moulded text, ridges, bumps, and holes make a cup harder to clean.

Bell-shaped cups

Bell-shaped menstrual cups come in many different shapes

Bell-shaped menstrual cups come in many different shapes Most manufacturers make at least two different sizes, sometimes confusingly labelled

Most manufacturers make at least two different sizes, sometimes confusingly labelled Softer bell-shaped cups may be more comfortable for some, but firmer cups may have a better seal

Softer bell-shaped cups may be more comfortable for some, but firmer cups may have a better seal A stemless, coloured menstrual cup with an asymmetrical rim to fit a tilted cervix.

A stemless, coloured menstrual cup with an asymmetrical rim to fit a tilted cervix.

| Size category | Length (excluding stem) | Capacity | Rim diameter | Firmness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 40-50mm | 15-25mL | 36-40mm | soft to medium |

| Medium | 45-55mm | 20-30mL | 41-44mm | soft to medium |

| Large | 48-58mm | 30-40mL | 45-48mm | medium to hard |

Bell-shaped menstrual cups all have a wall thickness of about 2mm. They vary in length, capacity, firmness, and external diameter of the rim. This accommodates variety in anatomy, flow quantity, and personal preferences for firmness.

While vaginal tenting causes the cervix to retract during sexual arousal, it is normally located within centimeters of the vaginal opening; 45-55mmm is a medium height. Cups are available in lengths from about 30-80mm, with 40-60mm lengths being common; most menstrual discs are shallower than most bell-shaped cups. Some manufacturers sell several sizes of cup that are all the same length.

Cups must be short enough that the cervix does not push the cup into contact with the vulva, where it may be uncomfortable. If the cervix sits particularly low or is tilted, a shorter cup may needed. A cup which is too short may sit too far up to remove easily.

Many bell-shaped cups have stems. The stems can be trimmed to shorten the cup, giving stemmed cups a minimum and maximum length; instructions for trimming are generally included with the cup. Some cups are made in two parts, with a separate stem passing through a hole in the cup; these separate stems, unlike normal one-piece stems, can be pulled to break the seal, and were designed to make removing the cup with low dexterity easier. There also exist cups with valves in the stem, which can be slowly drained without removing the cup. The UN counterrecommends hollow stems, because solid stems are easier to clean.

Ex vivo, small size cups hold about 15-25 ml, medium size cups 20-30 ml, and large cups 30-40 ml. The maximum capacity for large cups is about 50mL (ring-shaped cups generally hold a bit more than bell-shaped cups). Excessively high-volume cups can be uncomfortably large, so fit is prioritized.

Bell-shaped cups also vary by firmness or flexibility. Some manufacturers make the same cups in a range of firmness levels. A firmer cup pops open more easily after insertion and may hold a more consistent seal against the vaginal wall (preventing leaks), but some people find softer cups more comfortable to insert. The outside diameter of the rim will also affect seal and comfort.

Sizing

Cervix height is measured by touching the cervix with a fingertip, and using the thumb against the finger to mark the inner edge of the vaginal opening; the distance from the thumbnail to the tip of the finger is the height of the cervix. Cervix height varies slightly over the month, and is usually lowest on the first day of bleeding; minimum height is used for sizing menstrual cups. The cup length is generally taken to be equivalent to the cervix height, but as the cup rim will generally sit in the fornix, some may comfortably take a cup slightly longer than their cervical height. Fornix depth varies, but is usually between 1–5 cm (0.5-2 inches).

Manufacturers do not generally print cup dimensions on the box, but there are third-party tables of dimensions online. This forcers buyers to guess whether a cup will fit. A regulatory requirement for quantitative measurements, including a Young's modulus measurement of firmness, has been suggested. Research into what measurements would be most useful for selecting a well-sized cup is also needed.

Most brands sell a smaller and a larger size, but some sell up to five sizes, and differing firmnesses. Sizes are mostly labelled transparently, (e.g. "S", "M", and "L"), but some manufacturers label sizes with ordinal numbers (e.g. "0", "1", and "2"), alphabetic letters (e.g. "A" "B" and "C"), or euphemisms (such as "Petite", "Regular", and "Full fit"). Between one manufacturer's products, volume usually increases with number and position in the alphabet. Mostly, each larger size is slightly larger in all dimensions, but some manufacturers have sizes that differ in only one dimension (length, diameter, or capacity).

These sizes are not consistent between manufacturers. Manufacturers typically recommend the smaller size for under-30s who have not given birth vaginally and have a lighter flow, and the larger for everyone else. However, there is no medical evidence for sizing based on age or parity.

Ring-shaped cups or discs

A reusable silicone menstrual disc or ring. The thin-walled bowl is much more flexible than in a bell-shaped cup. The bowl on this cup is covered with a lattice of ridges on the inside.

A reusable silicone menstrual disc or ring. The thin-walled bowl is much more flexible than in a bell-shaped cup. The bowl on this cup is covered with a lattice of ridges on the inside. Side view of the same item, showing grooved rim and slightly asymmetrical, translucent bowl. Note moulding flash on rim, showing where the two-part mould joined.

Side view of the same item, showing grooved rim and slightly asymmetrical, translucent bowl. Note moulding flash on rim, showing where the two-part mould joined. Contraceptive diaphragms; one arced-rim diaphragm intended to fit sizes 65-80mm, and five in 5mm-increment diameters from 60-90mm. These are shaped similarly to menstrual discs, but they are overmoulded, silicone with a springy nylon core in the rim.

Contraceptive diaphragms; one arced-rim diaphragm intended to fit sizes 65-80mm, and five in 5mm-increment diameters from 60-90mm. These are shaped similarly to menstrual discs, but they are overmoulded, silicone with a springy nylon core in the rim. A side view of the same arced-rim diaphragm as in the previous picture. The bumps on the rim indicate where to pinch the rim in order to compress the device for insertion. The indentation near the hand is intended to aid removal. The S-shaped profile of the rim (as seen from the side) is intended to let the cup squish to fit a broader range of sizes.

A side view of the same arced-rim diaphragm as in the previous picture. The bumps on the rim indicate where to pinch the rim in order to compress the device for insertion. The indentation near the hand is intended to aid removal. The S-shaped profile of the rim (as seen from the side) is intended to let the cup squish to fit a broader range of sizes.

Ring-shaped cups (also called menstrual discs or rings) are often approximately hemispherical in shape, like a diaphragm, with a flexible ring rim and a soft, collapsible center. They collect menstrual fluid like menstrual cups, but sit in the vaginal fornix and stay in place by hooking behind the pubic bone. Menstrual discs come in both disposable and reusable varieties.

Ring-shaped cups are sized differently than bell-shaped cups. Fit is much less individual; the flexible bowl makes depth unimportant, and any ring-shaped cup between 60-70mm diameter will fit most people adequately. Sizing is measured in the same way as it is for contraceptive diaphragms, which fit in the same position.

A study of circular-rim diaphragms failed to find any proxy factor (like parity or weight) which would allow prediction of the size of diaphragm someone needed; it was necessary to take a measurement. As with contraceptive diaphragms, some "one-size-fits-all" cups have slightly oval or pear-shaped rims, and some have rims that arch (as seen from the side), increasing the range of sizes that fit. A contraceptive diaphragm using these techniques was found to fit 98% of volunteers in a multicenter study (everyone with a size of 65-80mm). A disc which is too big or too small will leak.

Ring-shaped cups come in diameters from 53mm to 80mm, as of 2024. They have some advantages over bell-shaped cups, including that they have a higher ex-vivo capacity (40-80ml), enable bloodless period sex, and are more comfortable for some users. Disadvantages include messier removal and more difficulty learning to insert them than for bell-shaped cups.

Some ring-shaped cups have removal aids. These may be stringlike stems, notches (dents in the outside of the bowl), and pull loops (like the ring-pull tab of a drinks can, or like a strap running parallel to the rim), and some have hybrid looped notches (with a strap across the rim of the notch). Notched or looped disks may rotate in the body so that the grip is out of reach, so some cups have three notches/loops spaced around the circumference of the cup. Notches reduce cup volume. Removal aids like pull loops make ring-shaped cups easier to remove without spilling, but they may chafe, and can be harder to clean.

Some menstrual rings have ribbed membranes. It is difficult to mould thin membranes; the silicone or plastic has to flow into a very narrow part of the mould, and solidify only once it has filled the area. While it is possible to mould silicone membranes as thin as a quarter of a millimeter thick (0.1 in), it requires care. Adding ribs (linear thicker areas) to the membrane makes it easier to mould. It also stiffens the membrane. Stiffer membranes may be more noticeable during sex, and smoother, softer ones less noticeable. It is anecdotally claimed that the increase in surface area from the ridges allows ridged cups to hold more blood; and that they may reduce effective natural vaginal lubrication when worn during sex. Texture may also be added to the outside of the membrane for grip, although it is usually the rim that is gripped when removing the cup.

Rings with a slimmer rim can be easier to slide around the cervix. A thin spot in the rim can let the rim fold more tightly for insertion and removal. Some ring-shaped cups also have concentric grooves on the outside of the rim; these can be harder to clean than an ungrooved rim. Grooves add stiffness while using less material; see I-beam.

Firmer ring-shaped cups can be easier to get into place, as they are stiffer, but softer rings fold more easily and tightly, and may be more comfortable to insert and remove. Firmer disks are therefore often preferred by new users. Unlike in bell-shaped cups, firmness does not affect the seal of a properly-fitting ring-shaped cup.

Sizing

Size can be measured in the same way as for contraceptive diaphragms; the fore and middle fingers are inserted until the tip of the middle finger is in the posterior fornix (the hollow on the spinewards side of the cervix), and the thumb is used against the forefinger to mark where the bony pubic arch touches the index finger. The diagonal distance between the tip of the middle finger and the thumbnail is then measured. This is the diameter of circular rim needed. At this depth the side walls of the vagina are quite stretchy, so no side-to-side measurement is needed.

Sizing rings can also be used. Disposable menstrual discs are also similar in size to many reusable ones, and can be used to check if an ~70mm diameter fits.

Many brands have a one-size-fits-most approach. Some sell two or three sizes, based on qualitative cervix height (low or high) rather than age or previous births. While North American manufacturers do not generally give dimensions, third-party tables of disc diameters are available online. European manufacturers generally do give the metric dimensions of their products online.

For circular rims, the outside rim diameter should match the diaphragm size. For oval and slightly egg-shaped rims, the sizing should be similar, but taking an average of the two rim dimensions. For complex three-dimensional rims, the manufacturer should indicate the size range the cup will fit.

Materials and color

Cups are made from rubbers (elastomers). Most are made from silicone rubber; some are made from latex or thermoplastic rubber. Some contain other ingredients, such as colourants or cheap bulking fillers. Cups made from good-quality materials last longer.

A UN specification says that cups must be made of medical-grade silicone. There are multiple medical grades. Plastics can also be medical-grade. Some jurisdictions require the use of medical-grade materials, but others do not. Where permitted, cups may be made of cheaper food-grade materials. The same make and model of cup may be made of different materials in different legal jurisdictions.

In many jurisdictions, menstrual products need not list ingredients. Some places, including some US states, have enacted laws requiring food-style ingredient lists, with the percentage of each ingredient. These laws include menstrual cups, and have been supported by some cup manufacturers.

Base materials

Latex

Early cups were made from latex manufactured from plant sap (usually gutta-percha or indiarubber). Latex is biodegradable. Latex allergy is common; around 4% of the general population worldwide has it, and repeated exposure makes a person more likely to develop it. Biologically-sourced latex may be brown or amber-coloured (see natural rubber).

Latex can harden over time.

Silicone rubber

Most brands use a silicone rubber (also called a silicone elastomer) as the material for their menstrual cups. Silicone is durable and hypoallergenic. Menstrual cups made from silicone are reusable for up to 10 years. The majority of menstrual cups on the market are reusable, rather than disposable.

Most brands, and all reputable ones, state that they use a medical-grade silicone. A UN specification requires medical-grade silicone. In most regulation systems, there are multiple subgrades of medical-grade silicones. For instance, in the US, class V and class VI are medical grades. Class VI is subgrouped into non-implantable (or medical-healthcare grade), shortterm-implantable, and longterm-implantable (with 30 days or more being long-term). Menstrual cups are commonly made of non-implantable medical-grade silicone. There are not specific grades of silicone rubber for long-term mucous membrane contact.

There are also non-regulatory distinctions. Most cups are made from liquid silicone rubber (LSR), but some seem to be made from high-consistency rubber (HCR). While LSR is indeed liquid, HCR is a putty-like material, which makes for differences in the manufacturing process. The former generally uses platinum catalysts to initiate curing (setting); the latter mostly uses peroxide catalysts.

While silicone rubbers, as polymers, are inert and hypoallergenic, the corresponding monomers are not. Silicone menstrual cups must therefore be fully cured before use. Heat accelerates curing.

Silicone rubbers also come in a range of Shore A hardnesses; a Shore hardness of 10 is gumlike, softer than some sponges and foams (chewing gum is about 20), while 80 is harder than the heel of a shoe. The firmness of a cup will be affected by the firmness of the material, but also its shape and dimensions.

Plastic

Plastics are also used for menstrual cups. The plastics used are generally thermoplastics (plastics that soften when heated, and can therefore be heat-moulded). They are also generally rubbery or elastomeric. The thermoplastic elastomers used in plastic cups are often unspecified, but are often of some medical grade.

The same brand and model of product may be made with different grades of plastic in different jurisdictions, with medical-grade plastic in jurisdictions that require it, and food-grade plastic in those that don't. This may be reflected in the price.

Colourants and other additives

The silicone or thermoplastics which most brands of cups are produced are naturally colorless and translucent. Several brands offer colored cups as well as, or instead of the colorless ones. A UN specification says that cups must be made of medical-grade silicone, and may include additives like "elastomer, dye or colorant", but no more than 0.5%. It also requires that the additives are non-toxic, non-carcinogenic, non-mutagenic, and do not cause skin irritation or skin sensitization.

Manufacturers generally do not specify what colourants they use, even on request.

In jurisdictions where cups are classed as medical devices, the colourants generally also have to be medical-grade, and fuse permanently to the raw material so that they cannot leach out. In jurisdictions where menstrual cups are classed as consumer devices, colourants need not be medical-grade. Some manufacturers use colourants certified for use in plastics intended to come in contact with food, for use in toys, and for use in consumer electronics. In some cases, a broader range of colours are available in jurisdictions where menstrual cups are not classed medical devices, and food-grade dyes can be used. The same brand and model of product may be made with different grades of colourant in different jurisdictions.

Because silicone rubbers are relatively expensive, some dodgier manufacturers mix cheaper fillers into their silicone. These fillers are typically not tested for safety. Such cups may or may not whiten when stretched only a small amount.

Manufacturing

Material must be treated carefully during manufacture to avoid contaminating it. ISO certification is used for silicone manufacturing processes, and is required for regulatory approval in some jurisdictions, like Canada.

Injection molding of liquid silicone rubber is used to make most cups. The setup costs (moulds etc.) are significant, so new designs are generally made in runs of about 4000 or more; production runs of existing designs are generally of about 500 or more at a time.

Larger production runs make for cheaper cups, because there are fixed set-up costs (it takes money to design a cup, set up a production run, and to clean up afterwards). Experience curve effects also reduce costs as more cups are made, including for repeated production runs of the same or similar cups. For example, for an extremely complex overmoulding of silicone on a shaped nylon spring, used for a contraceptive diaphragm, costs on a production run of 500 in 2010 were $20 US per item, while by 2013, batches of 10,000 and improvements in the manufacturing process had brought the cost down to $5 per item. By 2016, further improvements in manufacturing techniques had reduced the reject rate, making the product cheaper. See costs section, below, for non-manufacturing costs.

Good manufacturing will not show flash or conspicuous mould lines. Gate marks from the sprues of the mould may also be visible on some cups.

Regulation

Regulation varies by jurisdiction. Some international standards are used in multiple jurisdictions, especially those from the International Standards Association. Menstrual cup manufacturers seek and advertise ISO 13485 certification. ISO 13485 (quality management for the design and manufacturing of medical devices) and ISO 10993 (biocompatibility of medical devices) are both used for menstrual cups. ISO 14024 is an ecolabel which may be used by any manufacturer achieving certification to that standard; it is also used for some menstrual cups. While ISO standards are none-binding, specific ISO certifications may be legally required by some jurisdictions.

Many manufacturers comply with regulations in multiple jurisdictions. They may vary their products in order to do so, using cheaper materials and methods in jurisdictions where they are allowed.

Australia

Australia changed its regulatory environment in 2018, exempting menstrual cups from an obligation to register on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). Australia requires certain package labelling.

Canada

Canada regulates menstrual cups (like tampons and other insertables) as Class II medical devices. In Canada this means that they must be licensed by Health Canada before being advertised, imported, or sold. There are standards for materials and manufacturing facilities; getting accreditation and meeting the requirements can take years. There is also separate strong regulation of sustainability claims. This regulation raises costs for Canadian manufacturers; large manufacturers have made statements approving of the regulatory environment, though they complain about online competition from laxer jurisdictions.

Menstrual cups that meet the regulatory requirements to be sold in the United States may not be able to meet the requirements in Canada. This means that some menstrual cups manufactured in Canada are sold in the United States, but not in Canada.

EU

The EU does not regulate menstrual cups as medical devices, but categorizes them as "general products", under the General Product Safety Directive (now replaced by the General Product Safety Regulation). This means that manufacturers, by selling them, guarantee that they are safe, but do not face more oversight than manufacturers of other consumer products.

Some menstrual cups carry the EU Ecolabel, which requires minimum standards for packaging, pollution, emission reduction, and toxic substances in the finished product.

The EU has the power to order the removal of unsafe products, including from online shops. Manufacturers inside and outside the EU may voluntarily use the CE mark on packaging to assert that a product meets EU regulations.

Some EU manufacturers voluntarily got ISO certifications.

South Korea

Menstrual cups are categorized as "quasi-drugs" in South Korea. On the 7th of December 2017, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety approved the first menstrual cup for sale in South Korea, after a process involving the submission of data from a three-cycle clinical trial on effectiveness, and screening for ten highly hazardous volatile organic compounds.

US

The US regulates menstrual cups as Class II medical devices, but this does not mean the same thing as in Canada. The manufacturers of the silicone, the manufacturer that shapes it into cups, and the vendor, must all be registered with the FDA (using a 510(k) premarket notification and clearance) for a product to be sold legally in the United States. They must submit the required paperwork detailing their manufacturing process and similarity to existing products, and provide contact information. The US regulates the end products, but not the materials. Menstrual cups, unlike tampons, do not require premarket review.

Some cups claim to be "FDA approved". The Food and Drug administration does not approve Class II medical devices, only Class III medical devices. Menstrual cups are categorized as class II, not class III, so they cannot be "approved", only "cleared", and these claims are inaccurate.

The FDA requires certain product labelling on (or in) all packaging.

Cost

The costs for menstrual cups vary widely, from US$0.70 to $47 per cup, with a median cost of $23.35 (based on a 2019 review of 199 brands of menstrual cups available in 99 countries). Regulatory environment can have a strong effect on the price, because compliance may be time-consuming and costly. For manufacturing costs, see manufacturing section, above.

Reusable menstrual products (including reusable menstrual cups) are more economical than disposable pads or tampons. The same 2019 review looked at costs across seven countries and found that, over 10 years, a menstrual cup costs $460.25 less than 12 disposable pads per period and $304.25 less than 12 tampons per period.

Despite the long-term cost savings, the upfront cost of a menstrual cup is a barrier for some.

Environmental impact

Since they are reusable, menstrual cups help to reduce solid waste. Some disposable menstrual pads and plastic tampon applicators can take 25 years to break down in the ocean and can cause a significant environmental impact. Biodegradable sanitary options are also available, and these decompose in a short period of time, but they must be composted, and not disposed of in a landfill.

When considering a 10-year time period, waste from consistent use of a menstrual cup is only a small fraction of the waste of pads or tampons. For example, if compared with using 12 pads per period, use of a menstrual cup would produce only 0.4% of the plastic waste.

Each year, an estimated 20 billion pads and tampons are discarded in North America. They typically end up in landfills or are incinerated, which can have a great impact on the environment. Most of the pads and tampons are made of cotton and plastic. Plastic takes about 50 or more years and cotton starts degrading after 90 days if it is composted.

Given that the menstrual cup is reusable, its use greatly decreases the amount of waste generated from menstrual cycles, as there is no daily waste and the amount of discarded packaging decreases as well. After their life span is over, silicone cups can be burned or sent to a landfill. Alternatively, one brand offers a recycling program and some hospitals are able to recycle medical grade silicone, including cups. Cups made from TPE can be recycled in areas that accept #7 plastics. Rubber cups are compostable.

Menstrual cups may be emptied into a small hole in the soil or in compost piles, since menstrual fluid is a valuable fertilizer for plants and any pathogens of sexually transmitted diseases will quickly be destroyed by soil microbes. The water used to rinse the cups can be disposed of in the same way. This reduces the amount of wastewater that needs to be treated.

In developing countries, solid waste management is often lacking. Here, menstrual cups have an advantage over disposable pads or tampons as they do not contribute to the solid waste issues in the communities or generate embarrassing refuse that others may see.

History

Menstrual cups may have been inspired by other types of vaginal inserts used throughout history. Vaginal inserts had various purposes from birth control, enabling abortions, to supporting a prolapsed uterus. The first version of what we would now call a menstrual cup was a rubber sack attached to a rubber ring created by S.L. Hockert in 1867, which was patented in the United States. An early version of a bullet-shaped menstrual cup was patented in 1932, by the midwifery group of McGlasson and Perkins. Leona Chalmers patented the first usable commercial cup in 1937. Other menstrual cups were patented in 1935, 1937, and 1950. The Tassaway brand of menstrual cups was introduced in the 1960s, but it was not a commercial success. Early menstrual cups were made of rubber. The first menstrual-cup applicator was mentioned in a 1968 Tassaway patent; there are also 21st-century versions, but they have not been a commercial success, as of 2024.

No medical research was conducted to ensure that menstrual cups were safe prior to introduction on the market. Early research in 1962 evaluated 50 volunteers using a bell-shaped cup. The researchers obtained vaginal smears, gram stains, and basic aerobic cultures of vaginal secretions. Vaginal speculum examination was performed, and pH was measured. No significant changes were noted. This report was the first containing extensive information on the safety and acceptability of a widely used menstrual cup that included both preclinical and clinical testing and over 10 years of post-marketing surveillance.

In 1987, another latex rubber menstrual cup, The Keeper, was manufactured in the United States. This proved to be the first commercially viable menstrual cup and it is still available today. The first silicone menstrual cup was the UK-manufactured Mooncup in 2001. Most menstrual cups are now manufactured from medical grade silicone properties.

An early menstrual disc, the Gynaeseal, was developed by Dr John Cattanach in 1989, but never found commercial success. In 1997, the Instead Feminine Protection Cup began to be sold across the United States. Designed by Audrey Contente, the disposable disc was made of Kraton. In 2018, reusable silicone discs were introduced. As of 2021, there were ten brands of discs available for purchase in various markets.

Menstrual cups are becoming more popular worldwide, with many different brands, shapes, and sizes on the market. Most are reusable, though there is at least one brand of disposable menstrual cups currently manufactured.

Some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and companies have begun to propose menstrual cups to women in developing countries since about 2010, for example in Kenya and South Africa. Menstrual cups are regarded as a low-cost and environmentally friendly alternative to sanitary cloth, expensive disposable pads, or "nothing" – the reality for many women in developing countries.

Acceptability studies

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2024) |

In a randomized controlled feasibility study in rural western Kenya, adolescent primary school girls were provided with menstrual cups or menstrual pads instead of traditional menstrual care items of cloth or tissue. Girls provided with menstrual cups had a lower prevalence of sexually transmitted infections than control groups. Also, the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis was lower among cup users compared with menstrual pad users or those continuing other usual practice.

Society and culture

Public funding for menstrual cups

The municipality of Alappuzha in Kerala, India launched a project in 2019 and gave away 5,000 menstrual cups for free to residents. The purpose of this was to encourage the use of these cups instead of non-biodegradable menstrual pads to reduce waste production.

In 2022, Kumbalangi, a village in Kerala, became India's first sanitary-napkin-free panchayat under a project called "Avalkkayi", which gave away 5,700 menstrual cups for free.

In 2022, the Spanish government began distributing free menstrual cups through public institutions (such as schools, prisons, and health facilities).

In March 2024, Catalonia, in Spain, started supplying free menstrual cups as part of the "My period, my rules" initiative. The universal public healthcare system supplied one menstrual cup, one pair of period underwear, and two packages of reusable cloth menstrual pads per person, available through local pharmacies. The program covers 2.5 million people and cost the Catalan government €8.5 million (3.40 euros / 3.68 US dollars per person). The program was undertaken for equity, poverty reduction, taboo reduction, and environmental benefits. It is expected to reduce waste from single-use menstrual hygiene products, which had been 9000 tons per year, according to the Catalan government.

Developing countries

Further information: Menstrual hygiene management

Menstrual cups can be useful as a means of menstrual hygiene management for people in developing countries where access to affordable sanitary products may be limited. A lack of affordable hygiene products means inadequate, unhygienic alternatives are often used, which can present a serious health risk. Menstrual cups offer a long-term solution compared to some other menstrual hygiene products because they do not need to be replaced monthly.

Cultural aspects

Further information: Culture and menstruationMenstrual hygiene products that need to be inserted into the vagina can be unacceptable for cultural reasons. There are myths that they interfere with female reproductive organs and that they cause females to "lose their virginity".

There is no evidence that tampon use commonly causes trauma to the hymen. Hymens vary, and septate, cribriform or microperforate hymens, rarer physiological variations, may interfere with tampon use. Some ring-shaped menstrual cups are no bulkier than a tampon when folded as recommended.

Inserting objects (including penises) into the vagina may or may not affect the hymen. Some cultures wrongly think that the state of the hymen can give evidence of virginity, and wrongly believe that inserting anything into the vagina will "break" the hymen. This can discourage youths from using cups.

Despite common cultural beliefs, the state of a hymen cannot be used to prove or disprove virginity. Penile penetration does not lead to predictable changes to female genital organs; after puberty, hymens are highly elastic and can stretch during penetration without trace of injury. Females with a confirmed history of sexual abuse involving genital penetration may have normal hymens. Young females who say they have had consensual sex mostly show no identifiable changes in the hymen. Hymens rarely completely cover the vagina, hymens naturally have irregularities in width, and hymens can heal spontaneously without scarring. Many women do not bleed on having vaginal sex for the first time, hymens may not bleed significantly when torn, and vaginal walls may bleed significantly when torn.

There has been one news report of the stem of a bell-shaped cup passing outwards through a small side hole in a septate hymen (a hymen with more than one opening), causing pain on attempted removal. The woman had the problem diagnosed and the cup removed at a hospital. She had previously used the cup without problems for four years. Some examine their hymen with a mirror before using a menstrual cup.

See also

References

- "Menstrual Cup Materials Explained : Silicone, Latex & Thermoplastic Elastomer (TPE)". MeLuna USA. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- "Menstrual Cups Made from Thermoplastic Elastomer (TPE)". MeLuna USA. 16 October 2023. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ Ultimo C (16 November 2023). "Top Menstrual Cup Questions, Answered". Period Nirvana. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- Elizabeth Gunther Stewart, Paula Spencer: The V Book: A Doctor's Guide to Complete Vulvovaginal Health, Bantam Books, 2002, Seiten 96 und 97, ISBN 0-553-38114-8.

- Leslie Garrett, Peter Greenberg: The Virtuous Consumer: Your Essential Shopping Guide for a Better, Kinder and Healthier World, New World Library, 2007, Seiten 17 bis 19, ISBN 1-930722-74-5.

- ^ "Menstrual Cup Specifications — General description" (PDF). United Nations Population Fund. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Friberg M, Woeller K, Iberi V, Mancheno PP, Riedeman J, Bohman L, et al. (2023). "Development of in vitro methods to model the impact of vaginal lactobacilli on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation on menstrual cups as well as validation of recommended cleaning directions". Frontiers in Reproductive Health. 5: 1162746. doi:10.3389/frph.2023.1162746. PMC 10475951. PMID 37671283.

- Gallo MF, Grimes DA, Schulz KF (2002). "Cervical cap versus diaphragm for contraception". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002 (4): CD003551. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003551. PMC 8719323. PMID 12519602.

- ^ Rosas K. "Menstrual Cup Comparison Chart". Period Nirvana. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- text=Cervical caps come in internal diameters of 22-31mm, while bell-shaped cups come in sizes of ~31-53mm external diameter and as long as the wearer's cervix height permits.

- ^ Hendricks S (10 November 2021). "10 things I learned from testing every menstrual cup on the market". USA Today.

- Ultimo C (28 December 2023). "All of the Menstrual Disc Questions You Have, Answered". Period Nirvana. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- Hillard PJ, Hillard PA (2008). The 5-minute Obstetrics and Gynecology Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-7817-6942-6.

- ^ van Eijk AM, Zulaika G, Lenchner M, Mason L, Sivakami M, Nyothach E, et al. (August 2019). "Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Public Health. 4 (8): e376 – e393. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30111-2. PMC 6669309. PMID 31324419.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rosas K (5 October 2020). "Menstrual Cup or Disc - Which to choose?". Period Nirvana. Archived from the original on 12 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- Shastry S (12 July 2018). "5 Frequent Questions of Cup-Curious Folks!". SochGreen. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "The Best Menstrual Cup for Sports Enthusiasts and Athletes". Ruby Cup. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Eijk AM, Zulaika G, Lenchner M, Mason L, Sivakami M, Nyothach E, et al. (1 August 2019). "Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Public Health. 4 (8): e376 – e393. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30111-2. ISSN 2468-2667. PMC 6669309. PMID 31324419.

- see next paragraph

- "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- "COMMISSION DECISION (EU) 2023/1809 of 14 September 2023 establishing the EU Ecolabel criteria for absorbent hygiene products and for reusable menstrual cups". Official Journal of the European Union. 22 September 2023.

- Hale S (21 July 2022). "Menstrual Disc 101: How to Use One and Who They're For". Mira. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- Mathews D (13 December 2022). "Menstrual Cup: An Alternative To Tampons? - Fitt Feast". Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ North BB, Oldham MJ (February 2011). "Preclinical, clinical, and over-the-counter postmarketing experience with a new vaginal cup: menstrual collection". Journal of Women's Health. 20 (2): 303–11. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1929. PMC 3036176. PMID 21194348.

- US 70865 Improvement in menstrual receiver A 1867 patent describes a sack fitting partly or wholly inside the vagina, suspended from a ring around the cervix, but with the ring held up by a U-shaped wire, which is fastened to the sack at one end and to a belt at the other. Quote:"I construct my menstrual receiver by forming a cup-shaped ring, a, made of rubber, gum, gold, silver, or any suitable substance, which may be made round, or elliptical, or of any shape to fit the os uteri. Around the lower orifice of ring is attached a sack or bag, b, made of rubber or any suitable materials. The ring a rests-around the os uteri, and the bag b rests entirely in the vagina, or may be made of such length as to rest parily outside and partly inside. I insert a small sponge in bag b to absorb the menstrual flux."

- ^ US 49915 (1865)US 626159 (1899)

- US 574378

- ^ Eveleth R (13 February 2024). "The Best Menstrual Cups and Discs". Wirecutter. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ Crofts T (2012). Menstruation hygiene management for schoolgirls in low-income countries. Loughborough: Water, Engineering and Development Center (WEDC), Loughborough University. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Rosas K (24 November 2020). "Avoid These Menstrual Cup Dangers & Missteps". Period Nirvana. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Manley H, Hunt JA, Santos L, Breedon P (January 2021). "Comparison between menstrual cups: first step to categorization and improved safety". Women's Health. 17: 17455065211058553. doi:10.1177/17455065211058553. PMC 8606723. PMID 34798792.

- How to use an Instead Softcup, Wikihow