Palaeography (UK) or paleography (US; ultimately from Ancient Greek: παλαιός, palaiós, 'old', and γράφειν, gráphein, 'to write') is the study and academic discipline of the analysis of historical writing systems, the historicity of manuscripts and texts, subsuming deciphering and dating of historical manuscripts, including the analysis of historic penmanship, handwriting script, signification and printed media. It is primarily concerned with the forms, processes and relationships of writing and printing systems as evident in a text, document or manuscript; and analysis of the substantive textual content of documents is a secondary function. Included in the discipline is the practice of deciphering, reading, and dating manuscripts, and the cultural context of writing, including the methods with which writing and printing of texts, manuscripts, books, codices and tomes, tracts and monographs, etcetera, were produced, and the history of scriptoria. This discipline is important for understanding, authenticating, and dating historic texts. However, in the absence of additional evidence, it cannot be used to pinpoint exact dates.

The discipline is one of the auxiliary sciences of history, and is considered to have been founded by Jean Mabillon with his work De re diplomatica, published in 1681, which was the first textbook to address the subject. The term palaeography was coined by Bernard de Montfaucon with the publication of his work on Greek palaeography, the Palaeographia Graeca, in 1708.

Application

Palaeography is an essential skill for many historians, semioticians and philologists, as it addresses a suite of interrelated lines of inquiry. First, since the style of an alphabet, grapheme or sign system set within a register in each given dialect and language has evolved constantly, it is necessary to know how to decipher its individual substantive, occurrence make-up and constituency. For example, assessing its characters and typology as they existed in various places, times and locations. In addition, for hand-written texts, scribes often use many abbreviations, and annotations so as to functionally aid speed, efficiency and ease of writing and in some registers to importantly save invaluable space of the medium. Hence, the specialist-palaeographer, philologist and semiotician must know how to, in the broadest sense, interpret, comprehend and understand them. Knowledge of individual letterforms, typographic ligatures, signs, typology, fonts, graphemes, hieroglyphics, and signification forms in general, subsuming punctuation, syntagm and proxemics, abbreviations and annotations; enables the palaeographer to read, comprehend and then to understand the text and/or the relationship and hierarchy between texts in suite. The palaeographer, philologist and semiotician must first determine language, then dialect and then the register, function and purpose of the text. That is, one must by necessity become expert in the formation, historicity and evolution of these languages and signification communities, and material communication events. Secondly, the historical usages of various styles of handwriting, common writing customs, and scribal or notarial abbreviations, annotations conventions, annexures, addenda and specifics of printed typology, syntagm and proxemics must be assessed as a collective undertaking. Philological knowledge of the register, language, vocabulary, and grammar generally used at a given time, place and circumstance may assist palaeographers to identify a hierarchy of texts in a suite through discourse analysis, determining the provenance of texts, identifying forgeries, interpolations and recensions with precision; eliciting a professional authenticity in documentation, textual and manuscript evaluation with view to producing a critical edition if required and a critical assessment of a given discourse event as rendered and set in a materiality or medium.

Knowledge of writing materials and discourse material production systems is foundational to the study of handwriting and printing events and to the identification of the periods in which a document or manuscript may have been produced. An important goal may be to assign the text a date and a place of origin, or determining which translations of a text are produced from which specific document or manuscript. This is why the palaeographer and attendant semiologists and philologists must take into account the style, substance and formation of the text, document and manuscript and the handwriting style and printed typology, grapheme typos and lexical and signification system(s) employed.

Document dating

Palaeography may be employed to provide information about the date at which a document was written. However, "paleography is a last resort for dating" and, "for book hands, a period of 50 years is the least acceptable spread of time" with it being suggested that "the 'rule of thumb' should probably be to avoid dating a hand more precisely than a range of at least seventy or eighty years". In a 2005 e-mail addendum to his 1996 "The Paleographical Dating of P-46" paper Bruce W. Griffin stated "Until more rigorous methodologies are developed, it is difficult to construct a 95% confidence interval for [New Testament] manuscripts without allowing a century for an assigned date." William Schniedewind went even further in the abstract to his 2005 paper "Problems of Paleographic Dating of Inscriptions" and stated: "The so-called science of paleography often relies on circular reasoning because there is insufficient data to draw precise conclusion about dating. Scholars also tend to oversimplify diachronic development, assuming models of simplicity rather than complexity".

Ancient Near East

Aramaic palaeography

See also: Aramaic alphabet, Hebrew alphabet, Mandaic script, Sogdian alphabet, and Syriac alphabet

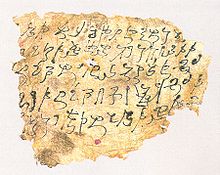

The Aramaic language was the international trade language of the Ancient Middle East, originating in what is modern-day Syria, between 1000 and 600 BC. It spread from the Mediterranean coast to the borders of India, becoming extremely popular and being adopted by many people, both with or without any previous writing system. The Aramaic script was written in a consonantal form with a direction from right to left. The Aramaic alphabet, a modified form of Phoenician, was the ancestor of the modern Arabic and Hebrew scripts, as well as the Brahmi script, the parent writing system of most modern abugidas in India, Southeast Asia, Tibet, and Mongolia. Initially, the Aramaic script did not differ from the Phoenician, but then the Aramaeans simplified some of the letters, thickened and rounded their lines: a specific feature of its letters is the distinction between ⟨d⟩ and ⟨r⟩. One innovation in Aramaic is the matres lectionis system to indicate certain vowels. Early Phoenician-derived scripts did not have letters for vowels, and so most texts recorded just consonants. Most likely as a consequence of phonetic changes in North Semitic languages, the Aramaeans reused certain letters in the alphabet to represent long vowels. The letter aleph was employed to write /ā/, he for /ō/, yod for /ī/, and vav for /ū/.

Aramaic writing and language supplanted Babylonian cuneiform and Akkadian language, even in their homeland in Mesopotamia. The wide diffusion of Aramaic letters led to its writing being used not only in monumental inscriptions, but also on papyrus and potsherds. Aramaic papyri have been found in large numbers in Egypt, especially at Elephantine—among them are official and private documents of the Jewish military settlement in 5 BC. In the Aramaic papyri and potsherds, words are separated usually by a small gap, as in modern writing. At the turn of the 3rd to 2nd centuries BC, the heretofore uniform Aramaic letters developed new forms, as a result of dialectal and political fragmentation in several subgroups. The most important of these is the so-called square Hebrew block script, followed by Palmyrene, Nabataean, and the much later Syriac script.

Aramaic is usually divided into three main parts:

- Old Aramaic (in turn subdivided into Ancient, Imperial, Old Eastern and Old Western Aramaic)

- Middle Aramaic, and

- Modern Aramaic of the present day.

The term Middle Aramaic refers to the form of Aramaic which appears in pointed texts and is reached in the 3rd century AD with the loss of short unstressed vowels in open syllables, and continues until the triumph of Arabic.

Old Aramaic appeared in the 11th century BC as the official language of the first Aramaean states. The oldest witnesses to it are inscriptions from northern Syria of the 10th to 8th centuries BC, especially extensive state treaties (c. 750 BC) and royal inscriptions. The early Old Ancient should be classified as "Ancient Aramaic" and consists of two clearly distinguished and standardised written languages, the Early Ancient Aramaic and the Late Ancient Aramaic. Aramaic was influenced at first principally by Akkadian, then from the 5th century BC by Persian and from the 3rd century BC onwards by Greek, as well as by Hebrew, especially in Palestine. As Aramaic evolved into the imperial language of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the script used to write it underwent a change into something more cursive. The best examples of this script come from documents written on papyrus from Egypt. About 500 BC, Darius I (522–486) made the Aramaic used by the imperial administration into the official language of the western half of the Achaemenid Empire. This so-called "Imperial Aramaic" (the oldest dated example, from Egypt, belonging to 495 BC) is based on an otherwise unknown written form of Ancient Aramaic from Babylonia. In orthography, Imperial Aramaic preserves historical forms—alphabet, orthography, morphology, pronunciation, vocabulary, syntax and style are highly standardised. Only the formularies of the private documents and the Proverbs of Ahiqar have maintained an older tradition of sentence structure and style. Imperial Aramaic immediately replaced Ancient Aramaic as a written language and, with slight modifications, it remained the official, commercial and literary language of the Near East until gradually, beginning with the fall of the Achaemenids in 331 BC and ending in the 4th century AD, it was replaced by Greek, Persian, the eastern and western dialects of Aramaic and Arabic, though not without leaving its traces in the written form of most of these. In its original Achaemenid form, Imperial Aramaic is found in texts of the 5th to 3rd centuries BC. These come mostly from Egypt and especially from the Jewish military colony of Elephantine, which existed at least from 530 to 399 BC.

Greek palaeography

Further information: History of the Greek alphabet and Archaic Greek alphabets See also: Inscriptiones Graecae

A history of Greek handwriting must be incomplete owing to the fragmentary nature of evidence. If one rules out the inscriptions on stone or metal, which belong to the science of epigraphy, there is practically a dependence on papyri from Egypt for the period preceding the 4th or 5th century AD, the earliest of which take back our knowledge only to the end of the 4th century BC. This limitation is less serious than might appear, since the few manuscripts not of Egyptian origin which have survived from this period, like the parchments from Avroman or Dura, the Herculaneum papyri, and a few documents found in Egypt but written elsewhere, reveal a uniformity of style in the various portions of the Greek world; however, differences can be discerned, with it being probable that distinct local styles could be traced were there more material to analyze.

Further, during any given period several types of hand may exist together. There was a marked difference between the hand used for literary works (generally called "uncials" but, in the papyrus period, better styled "book-hand") and that of documents ("cursive") and within each of these classes several distinct styles were employed side by side; and the various types are not equally well represented in the surviving papyri.

The development of any hand is largely influenced by the materials used. To this general rule the Greek script is no exception. Whatever may have been the period at which the use of papyrus or leather as a writing material began in Greece (and papyrus was employed in the 5th century BC), it is highly probable that for some time after the introduction of the alphabet the characters were incised with a sharp tool on stones or metal far oftener than they were written with a pen. In cutting a hard surface, it is easier to form angles than curves; in writing the reverse is the case; hence the development of writing was from angular letters ("capitals") inherited from epigraphic style to rounded ones ("uncials"). But only certain letters were affected by this development, in particular ⟨E⟩ (uncial ⟨ε⟩), ⟨Σ⟩ (⟨c⟩), ⟨Ω⟩ (⟨ω⟩), and to a lesser extent ⟨A⟩ (⟨α⟩).

Ptolemaic period

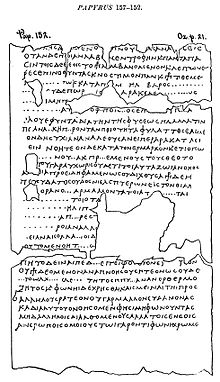

The earliest Greek papyrus yet discovered is probably that containing the Persae of Timotheus, which dates from the second half of the 4th century BC and its script has a curiously archaic appearance. ⟨E⟩, ⟨Σ⟩, and ⟨Ω⟩ have the capital form, and apart from these test letters the general effect is one of stiffness and angularity. More striking is the hand of the earliest dated papyrus, a contract of 311 BC. Written with more ease and elegance, it shows little trace of any development towards a truly cursive style; the letters are not linked, and though the uncial ⟨c⟩ is used throughout, ⟨E⟩ and ⟨Ω⟩ have the capital forms. A similar impression is made by the few other papyri, chiefly literary, dating from about 300 BC; ⟨E⟩ may be slightly rounded, ⟨Ω⟩ approach the uncial form, and the angular ⟨Σ⟩ occurs as a letter only in the Timotheus papyrus, though it survived longer as a numeral (= 200), but the hands hardly suggest that for at least a century and a half the art of writing on papyrus had been well established. Yet before the middle of the 3rd century BC, one finds both a practised book-hand and a developed and often remarkably handsome cursive.

These facts may be due to accident, the few early papyri happening to represent an archaic style which had survived along with a more advanced one; but it is likely that there was a rapid development at this period, due partly to the opening of Egypt, with its supplies of papyri, and still more to the establishment of the great Alexandrian Library, which systematically copied literary and scientific works, and to the multifarious activities of Hellenistic bureaucracy. From here onward, the two types of script were sufficiently distinct (though each influenced the other) to require separate treatment. Some literary papyri, like the roll containing Aristotle's Constitution of Athens, were written in cursive hands, and, conversely, the book-hand was occasionally used for documents. Since the scribe did not date literary rolls, such papyri are useful in tracing the development of the book-hand.

The documents of the mid-3rd century BC show a great variety of cursive hands. There are none from chancelleries of the Hellenistic monarchs, but some letters, notably those of Apollonius, the finance minister of Ptolemy II, to this agent, Zeno, and those of the Palestinian sheikh, Toubias, are in a type of script which cannot be very unlike the Chancery hand of the time, and show the Ptolemaic cursive at its best. These hands have a noble spaciousness and strength, and though the individual letters are by no means uniform in size there is a real unity of style, the general impression being one of breadth and uprightness. ⟨H⟩, with the cross-stroke high, ⟨Π⟩, ⟨Μ⟩, with the middle stroke reduced to a very shallow curve, sometimes approaching a horizontal line, ⟨Υ⟩, and ⟨Τ⟩, with its cross-bar extending much further to the left than to the right of the up-stroke, ⟨Γ⟩ and ⟨Ν⟩, whose last stroke is prolonged upwards above the line, often curving backwards, are all broad; ⟨ε⟩, ⟨c⟩, ⟨θ⟩ and ⟨β⟩, which sometimes takes the form of two almost perpendicular strokes joined only at the top, are usually small; ⟨ω⟩ is rather flat, its second loop reduced to a practically straight line. Partly by the broad flat tops of the larger letters, partly by the insertion of a stroke connecting those (like H, Υ) which are not naturally adapted to linking, the scribes produced the effect of a horizontal line along the top of the writing, from which the letters seem to hang. This feature is indeed a general characteristic of the more formal Ptolemaic script, but it is specially marked in the 3rd century BC.

Besides these hand of Chancery type, there are numerous less elaborate examples of cursive, varying according to the writer's skill and degree of education, and many of them strikingly easy and handsome. In some cursiveness is carried very far, the linking of letters reaching the point of illegibility, and the characters sloping to the right. ⟨A⟩ is reduced to a mere acute angle (⟨∠⟩), ⟨T⟩ has the cross-stroke only on the left, ⟨ω⟩ becomes an almost straight line, ⟨H⟩ acquires a shape somewhat like h, and the last stroke of ⟨N⟩ is extended far upwards and at times flattened out until it is little more than a diagonal stroke to the right. The attempt to secure a horizontal line along the top is here abandoned. This style was not due to inexpertness, but to the desire for speed, being used especially in accounts and drafts, and was generally the work of practised writers. How well established the cursive hand had now become is shown in some wax tablets of this period, the writing on which, despite the difference of material, closely resemble the hands of papyri.

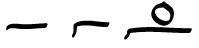

Documents of the late 3rd and early 2nd centuries BC show there is nothing analogous to the Apollonius letters, perhaps partly by the accident of survival. In the more formal types the letters stand rather stiffly upright, often without the linking strokes, and are more uniform in size; in the more cursive they are apt to be packed closely together. These features are more marked in the hands of the 2nd century. The less cursive often show am approximation to the book-hand, the letters growing rounder and less angular than in the 3rd century; in the more cursive linking was carried further, both by the insertion of coupling strokes and by the writing of several letters continuously without raising the pen, so that before the end of the century an almost current hand was evolved. A characteristic letter, which survived into the early Roman period, is ⟨T⟩, with its cross-stroke made in two portions (variants:![]() ). In the 1st century, the hand tended, so far as can be inferred from surviving examples, to disintegrate; one can recognise the signs which portend a change of style, irregularity, want of direction, and the loss of the feeling for style. A fortunate accident has preserved two Greek parchments written in Parthia, one dated 88 BC, in a practically unligatured hand, the other, 22/21 BC, in a very cursive script of Ptolemaic type; and though each has non-Egyptian features the general character indicates a uniformity of style in the Hellenistic world.

). In the 1st century, the hand tended, so far as can be inferred from surviving examples, to disintegrate; one can recognise the signs which portend a change of style, irregularity, want of direction, and the loss of the feeling for style. A fortunate accident has preserved two Greek parchments written in Parthia, one dated 88 BC, in a practically unligatured hand, the other, 22/21 BC, in a very cursive script of Ptolemaic type; and though each has non-Egyptian features the general character indicates a uniformity of style in the Hellenistic world.

The development of the Ptolemaic book-hand is difficult to trace, as there are few examples, mostly not datable on external grounds. Only for the 3rd century BC have we a secure basis. The hands of that period have an angular appearance; there is little uniformity in the size of individual letters, and though sometimes, notably in the Petrie papyrus containing the Phaedo of Plato, a style of considerable delicacy is attained, the book-hand in general shows less mastery than the contemporary cursive. In the 2nd century, the letters grew rounder and more uniform in size, but in the 1st century there is a certain disintegration perceptible, as in the cursive hand. Probably at no time did the Ptolemaic book-hand acquire such unity of stylistic effect as the cursive.

Roman period

Papyri of the Roman period are far more numerous and show greater variety. The cursive of the 1st century has a rather broken appearance, part of one character being often made separately from the rest and linked to the next letter. A form characteristic of the 1st and 2nd century and surviving after that only as a fraction sign (1⁄8) is ⟨η⟩ in the shape ![]() . By the end of the 1st century, there had been developed several excellent types of cursive, which, though differing considerably both in the forms of individual letters and in general appearance, bear a family likeness to one another. Qualities which are specially noticeable are roundness in the shape of letters, continuity of formation, the pen being carried on from character to character, and regularity, the letters not differing strikingly in size and projecting strokes above or below the line being avoided. Sometimes, especially in tax-receipts and in stereotyped formulae, cursiveness is carried to an extreme. In a letter of the prefect, dated in 209, we have a fine example of the Chancery hand, with tall and laterally compressed letters, ⟨ο⟩ very narrow and ⟨α⟩ and ⟨ω⟩ often written high in the line. This style, from at least the latter part of the 2nd century, exercised considerable influence on the local hands, many of which show the same characteristics less pronounced; and its effects may be traced into the early part of the 4th century. Hands of the 3rd century uninfluenced by it show a falling off from the perfection of the 2nd century; stylistic uncertainty and a growing coarseness of execution mark a period of decline and transition.

. By the end of the 1st century, there had been developed several excellent types of cursive, which, though differing considerably both in the forms of individual letters and in general appearance, bear a family likeness to one another. Qualities which are specially noticeable are roundness in the shape of letters, continuity of formation, the pen being carried on from character to character, and regularity, the letters not differing strikingly in size and projecting strokes above or below the line being avoided. Sometimes, especially in tax-receipts and in stereotyped formulae, cursiveness is carried to an extreme. In a letter of the prefect, dated in 209, we have a fine example of the Chancery hand, with tall and laterally compressed letters, ⟨ο⟩ very narrow and ⟨α⟩ and ⟨ω⟩ often written high in the line. This style, from at least the latter part of the 2nd century, exercised considerable influence on the local hands, many of which show the same characteristics less pronounced; and its effects may be traced into the early part of the 4th century. Hands of the 3rd century uninfluenced by it show a falling off from the perfection of the 2nd century; stylistic uncertainty and a growing coarseness of execution mark a period of decline and transition.

Several different types of book-hand were used in the Roman period. Particularly handsome is a round, upright hand seen, for example, in a British Museum papyrus containing Odyssey III. The cross-stroke of ⟨ε⟩ is high, ⟨Μ⟩ deeply curved and ⟨Α⟩ has the form ⟨α⟩. Uniformity of size is well attained, and a few strokes project, and these but slightly, above or below the line. Another type, well called by palaeographer Schubart the "severe" style, has a more angular appearance and not infrequently slopes to the right; though handsome, it has not the sumptuous appearance of the former. There are various classes of a less pretentious style, in which convenience rather than beauty was the first consideration and no pains were taken to avoid irregularities in the shape and alignment of the letters. Lastly may be mentioned a hand which is of great interest as being the ancestor of the type called (from its later occurrence in vellum codices of the Bible) the biblical hand. This, which can be traced back at least the late 2nd century, has a square, rather heavy appearance; the letters, of uniform size, stand upright, and thick and thin strokes are well distinguished. In the 3rd century the book-hand, like the cursive, appears to have deteriorated in regularity and stylistic accomplishment.

In the charred rolls found at Herculaneum are specimens of Greek literary hands from outside Egypt dating to c. 1 AD. A comparison with the Egyptian papyri reveals great similarity in style and shows that conclusions drawn from the henads of Egypt may, with caution, be applied to the development of writing in the Greek world generally.

Byzantine period

See also: Byzantine text-type

The cursive hand of the 4th century shows some uncertainty of character. Side by side with the style founded on the Chancery hand, regular in formation and with tall and narrow letters, which characterised the period of Diocletian, and lasted well into the century, we find many other types mostly marked by a certain looseness and irregularity. A general progress towards a florid and sprawling hand is easily recognisable, but a consistent and deliberate style was hardly evolved before the 5th century, from which unfortunately few dated documents have survived. Byzantine cursive tends to an exuberant hand, in which the long strokes are excessively extended and individual letters often much enlarged. But not a few hands of the 5th and 6th centuries are truly handsome and show considerable technical accomplishment. Both an upright and a sloping type occur and there are many less ornamental hands, but there gradually emerged towards the 7th century two general types, one (especially used in letters and contracts) a current hand, sloping to the right, with long strokes in such characters at ⟨τ⟩, ⟨ρ⟩, ⟨ξ⟩, ⟨η⟩ (which has the h shape), ⟨ι⟩, and ⟨κ⟩, and with much linking of letters, and another (frequent in accounts), which shows, at least in essence, most of the forms of the later minuscule. (cf. below.) This is often upright, though a slope to the right is quite common, and sometimes, especially in one or two documents of the early Arabic period, it has an almost calligraphic effect.

In the Byzantine period, the book-hand, which in earlier times had more than once approximated to the contemporary cursive, diverged widely from it.

Vellum and paper manuscripts

The change from papyrus to vellum involved no such modification in the forms of letters as followed that from metal to papyrus. The justification for considering the two materials separately is that after the general adoption of vellum, the Egyptian evidence is first supplemented and later superseded by that of manuscripts from elsewhere, and that during this period the hand most used was one not previously employed for literary purposes.

Uncial hand

See also: Uncial script

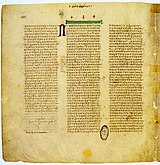

Pages from Codex Vaticanus (left) and Codex Marchalianus (right)

Pages from Codex Vaticanus (left) and Codex Marchalianus (right)

The prevailing type of book-hand during what in papyrology is called the Byzantine period, that is, roughly from AD 300 to 650, is known as the biblical hand. It went back to at least the end of the 2nd century and had had originally no special connection with Christian literature. In both vellum and paper manuscripts from 4th-century Egypt are other forms of script, particularly a sloping, rather inelegant hand derived from the literary hand of the 3rd century, which persisted until at least the 5th century. The three great early codices of the Bible are all written in uncials of the biblical type. In the Vaticanus, placed during the 4th century, the characteristics of the hand are least strongly marked; the letters have the forms characteristic of the type but without the heavy appearance of later manuscripts, and the general impression is one of greater roundness. In the Sinaiticus, which is not much later, the letters are larger and more heavily made; in the 5th-century Alexandrinus, a later development is seen with emphatic distinction of thick and thin strokes. By the 6th century, alike in vellum and in papyrus manuscripts, the heaviness had become very marked, though the hand still retained, in its best examples, a handsome appearance; but after this it steadily deteriorated, becoming ever more mechanical and artificial. The thick strokes grew heavier; the cross strokes of ⟨T⟩ and ⟨Θ⟩ and the base of ⟨Δ⟩ were furnished with drooping spurs. The hand, which is often singularly ugly, passed through various modifications, now sloping, now upright, though it is not certain that these variations were really successive rather than concurrent. A different type of uncials, derived from the Chancery hand and seen in two papyrus examples of the Festal letters despatched annually by the Patriarch of Alexandria, was occasionally used, the best known example being the Codex Marchalianus (6th or 7th century). A combination of this hand with the other type is also known.

Minuscule hand

The uncial hand lingered on, mainly for liturgical manuscripts, where a large and easily legible script was serviceable, as late as the 12th century, but in ordinary use it had long been superseded by a new type of hand, the minuscule, which originated in the 8th century, as an adaptation to literary purposes of the second of the types of Byzantine cursive mentioned above. A first attempt at a calligraphic use of this hand, seen in one or two manuscripts of the 8th or early 9th century, in which it slopes to the right and has a narrow, angular appearance, did not find favour, but by the end of the 9th century a more ornamental type, from which modern Greek script descended, was already established. It has been suggested that it was evolved in the Monastery of Stoudios at Constantinople. In its earliest examples it is upright and exact but lacks flexibility; accents are small, breathings square in formation, and in general only such ligatures are used as involve no change in the shape of letters. The single forms have a general resemblance (with considerable differences in detail) both to the minuscule cursive of late papyri, and to those used in modern Greek type; uncial forms were avoided.

In the course of the 10th century the hand, without losing its beauty and exactness, gained in freedom. Its finest period was from the 9th to the 12th century, after which it rapidly declined. The development was marked by a tendency

- to the intrusion, in growing quantity, of uncial forms which good scribes could fit into the line without disturbing the unity of style but which, in less expert hands, had a disintegrating effect;

- to the disproportionate enlargement of single letters, especially at the beginnings and ends of lines;

- to ligatures, often very fantastic, which quite changed the forms of letters;

- to the enlargement of accents, breathings at the same time acquiring the modern rounded form.

But from the first there were several styles, varying from the formal, regular hands characteristic of service books to the informal style, marked by numerous abbreviations, used in manuscripts intended only for a scholar's private use. The more formal hands were exceedingly conservative, and there are few classes of script more difficult to date than the Greek minuscule of this class. In the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries a sloping hand, less dignified than the upright, formal type, but often very handsome, was especially used for manuscripts of the classics.

Hands of the 11th century are marked in general (though there are exceptions) by a certain grace and delicacy, exact but easy; those of the 12th by a broad, bold sweep and an increasing freedom, which readily admits uncial forms, ligatures and enlarged letters but has not lost the sense of style and decorative effect. In the 13th and still more in the 14th centuries there was a steady decline; the less formal hands lost their beauty and exactness, becoming ever more disorderly and chaotic in their effect, while formal style imitated the precision of an earlier period without attaining its freedom and naturalness, and often appears singularly lifeless. In the 15th century, especially in the West, where Greek scribes were in request to produce manuscripts of the classical authors, there was a revival, and several manuscripts of this period, though markedly inferior to those of the 11th and 12th centuries, are by no means without beauty.

Accents, punctuation, and division of words

In the book-hand of early papyri, neither accents nor breathings were employed. Their use was established by the beginning of the Roman period, but was sporadic in papyri, where they were used as an aid to understanding, and therefore more frequently in poetry than prose, and in lyrical oftener than in other verse. In the cursive of papyri they are practically unknown, as are marks of punctuation. Punctuation was effected in early papyri, literary and documentary, by spaces, reinforced in the book-hand by the paragraphos, a horizontal stroke under the beginning of the line. The coronis, a more elaborate form of this, marked the beginning of lyrics or the principal sections of a longer work. Punctuation marks, the comma, the high, low and middle points, were established in the book-hand by the Roman period; in early Ptolemaic papyri, a double point (⟨:⟩) is found.

In vellum and paper manuscripts, punctuation marks and accents were regularly used from at least the 8th century, though with some differences from modern practice. At no period down to the invention of printing did Greek scribes consistently separate words. The book-hand of papyri aimed at an unbroken succession of letters, except for distinction of sections; in cursive hands, especially where abbreviations were numerous, some tendency to separate words may be recognised, but in reality it was phrases or groups of letters rather than words which were divided. In the later minuscule word-division is much commoner but never became systematic, accents and breathings serving of themselves to indicate the proper division.

China

See also: Chinese characters § History| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (May 2021) |

India

The view that the art of writing in India developed gradually, as in other areas of the world, by going through the stages of pictographic, ideographic and transitional phases of the phonetic script, which in turn developed into syllabic and alphabetic scripts was challenged by Falk and others in the early 1990s. In the new paradigm, Indian alphabetic writing, called Brahmi, was discontinuous with earlier, undeciphered, glyphs, and was invented specifically by King Ashoka for application in his royal edicts 250 BC. In the subcontinent, Kharosthi (clearly derived from the Aramaic alphabet) was used at the same time in the northwest, next to Brahmi (at least influenced by Aramaic) elsewhere. In addition, the Greek alphabet were also added to the Indian context after its penetration in the early centuries AD, with the Arabic alphabet following in the 13th century. After a lapse of a few centuries the Kharoṣṭhi script became obsolete; the Greek script in India went through a similar fate and disappeared. But the Brahmi and Arabic scripts endured for a much longer period. Moreover, there was a change and development in the Brahmi script which may be traced in time and space through the Maurya, Kuṣaṇa, Gupta and early medieval periods. The present-day Nāgarī script is derived from Brahmi. The Brahmi is also the ancestral script of most other Indian scripts, in northern and southern South Asia. Legends and inscriptions in Brahmi are engraved upon leather, wood, terracotta, ivory, stone, copper, bronze, silver and gold. Arabic got an important place, particularly in the royalty, during the medieval period and it provides rich material for history writing. The decipherment and subsequent development of Indus glyphs is also a matter for continuing research and discussion.

Most of the available inscriptions and manuscripts written in the above scripts—in languages like Prakrit, Pali, Sanskrit, Apabhraṃśa, Tamil and Persian—have been read and exploited for history writing, but numerous inscriptions preserved in different museums still remain undeciphered for lack of competent palaeographic Indologists, as there is a gradual decline in the subcontinent of such disciplines as palaeography, epigraphy and numismatics. The discipline of ancient Indian scripts and the languages they are written needs new scholars who, by adopting traditional palaeographic methods and modern technology, may decipher, study and transcribe the various types of epigraphs and legends still extant today.

The language of the earliest written records, that is, the Edicts of Ashoka, is Prakrit. Besides Prakrit, the Ashokan edicts are also written in Greek and Aramaic. Moreover, all the edicts of Ashoka engraved in the Kharoshthi and Brahmi scripts are in the Prakrit language: thus, originally the language employed in the inscriptions was Prakrit, with Sanskrit adopted at a later stage. Past the period of the Maurya Empire, the use of Prakrit continued in inscriptions for a few more centuries. In north India, Prakrit was replaced by Sanskrit by the end of the 3rd century, while this change took place about a century later in south India. Some of the inscriptions though written in Prakrit, were influenced by Sanskrit and vice versa. The epigraphs of the Kushana kings are found in a mixture of Prakrit and Sanskrit, while the Mathura inscriptions of the time of Sodasa, belonging to the first quarter of the 1st century, contain verses in classical Sanskrit. From the 4th century onwards, the Gupta Empire came to power and supported the Sanskrit language and literature.

In western India and also in some regions of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, Prakrit was used till the 4th century, mostly in the Buddhist writings though in a few contemporary records of the Ikshvakus of Nagarjunakonda, Sanskrit was applied. The inscription of Yajna Sri Satakarni (2nd century) from Amaravati is considered to be the earliest so far. The earlier writings (4th century) of Salankayanas of the Telugu region are in Prakrit, while their later records (belonging to the 5th century) are written in Sanskrit. In the Kannada speaking area, inscriptions belonging to later Satavahanas and Chutus were written in Prakrit. From the 4th century onwards, with the rise of the Guptas, Sanskrit became the predominant language of India and continued to be employed in texts and inscriptions of all parts of India along with the regional languages in the subsequent centuries. The copper-plate charters of the Pallavas, the Cholas and the Pandyas documents are written in both Sanskrit and Tamil. Kannada is used in texts dating from about the 5th century and the Halmidi inscription is considered to be the earliest epigraph written in the Kannada language. Inscriptions in Telugu began to appear from the 6th or 7th century. Malayalam made its beginning in writings from the 15th century onwards.

North India

In north India, the Brahmi script was used over a vast area; however, Ashokan inscriptions are also found using Kharoshthi, Aramaic and Greek scripts. With the advent of the Saka-Kshatrapas and the Kushanas as political powers in north India, the writing system underwent a definite change due to the use of new writing tools and techniques. Further development of the Brahmi script and perceivable changes in its evolutionary trend can be discerned during the Gupta period: in fact, the Gupta script is considered to be the successor of the Kushana script in north India.

From the 6th to about the 10th century, the inscriptions in north India were written in a script variously named, e.g., Siddhamatrika and Kutila ("Rañjanā script"). From the 8th century, Siddhamatrika developed into the Śāradā script in Kashmir and Punjab, into Proto-Bengali or Gaudi in Bengal and Orissa, and into Nagari in other parts of north India. Nagari script was used widely in northern India from the 10th century onwards. The use of Nandinagari, a variant of Nagari script, is mostly confined to the Karnataka region.

In central India, mostly in Madhya Pradesh, the inscriptions of the Vakatakas, and the kings of Sarabhapura and Kosala were written in what are known as "box-headed" and "nail-headed" characters. It may be noted that the early Kadambas of Karnataka also employed "nail-headed" characters in some of their inscriptions. During the 3rd–4th century, the script used in the inscriptions of Ikshvakus of Nagarjunakonda developed a unique style of letter-forms with elongated verticals and artistic flourishes, which did not continue after their rule.

South India

The earliest attested form of writing in South India is represented by inscriptions found in caves, associated with the Chalukya and Chera dynasties. These are written in variants of what is known as the Cave character, and their script differs from the Northern version in being more angular. Most of the modern scripts of South India have evolved from this script, with the exception of Vatteluttu, the exact origins of which are unknown, and Nandinagari, which is a variant of Devanagari that developed due to later Northern influence. In south India from the 7th century of the common era onwards, a number of inscriptions belonging to the dynasties of Pallava, Chola and Pandya are found. These records are written in three different scripts known as Tamil, Vattezhuttu and Grantha scripts, the last variety being used to write Sanskrit inscriptions. In the Kerala region, the Vattezhuttu script developed into a still more cursive script called Kolezhuthu during the 14th and 15th centuries. At the same time, the modern Malayalam script developed out of the Grantha script. The early form of the Telugu-Kannada script is found in the inscriptions of the early Kadambas of Banavasi and the early Chalukyas of Badami in the west, and Salankayana and the early Eastern Chalukyas in the east who ruled the Kannada and Telugu speaking areas respectively, during the 4th to 7th centuries.

List of South Indian scripts

- Brahmi script

- Chalukya and Chera cultures

- Grantha script

- Kannada script

- Malayalam script

- Nāgarī script and Nandinagari

- Tamil script (cf. also Abagada writing system)

- Telugu script

Latin

Further information: History of the Latin script See also: Corpus Inscriptionum LatinarumAttention should be drawn at the outset to certain fundamental definitions and principles of the science. The original characters of an alphabet are modified by the material and the implements used. When stone and chisel are discarded for papyrus and reed-pen, the hand encounters less resistance and moves more rapidly. This leads to changes in the size and position of the letters, and then to the joining of letters, and, consequently, to altered shapes. We are thus confronted at an early date with quite distinct types. The majuscule style of writing, based on two parallel lines, ADPL, is opposed to the minuscule, based on a system of four lines, with letters of unequal height, adpl. Another classification, according to the care taken in forming the letters, distinguishes between the set book-hand and the cursive script. The difference in this case is determined by the subject matter of the text; the writing used for books (scriptura libraria) is in all periods quite distinct from that used for letters and documents (epistolaris, diplomatica). While the set book-hand, in majuscule or minuscule, shows a tendency to stabilise the forms of the letters, the cursive, often carelessly written, is continually changing in the course of years and according to the preferences of the writers.

This being granted, a summary survey of the morphological history of the Latin alphabet shows the zenith of its modifications at once, for its history is divided into two very unequal periods, the first dominated by majuscule and the second by minuscule writing.

Overview

Jean Mabillon, a French Benedictine monk, scholar and antiquary, whose work De re diplomatica was published in 1681, is widely regarded as the founder of the twin disciplines of palaeography and diplomatics. However, the actual term "palaeography" was coined (in Latin) by Bernard de Montfaucon, a Benedictine monk, in the title of his Palaeographia Graeca (1708), which remained a standard work in the specific field of Greek palaeography for more than a century. With their establishment of palaeography, Mabillon and his fellow Benedictines were responding to the Jesuit Daniel Papebroch, who doubted the authenticity of some of the documents which the Benedictines offered as credentials for the authorisation of their monasteries. In the 19th century such scholars as Wilhelm Wattenbach, Leopold Delisle and Ludwig Traube contributed greatly to making palaeography independent from diplomatic. In the 20th century, the "New French School" of palaeographers, especially Jean Mallon, gave a new direction to the study of scripts by stressing the importance of ductus (the shape and order of the strokes used to compose letters) in studying the historical development of scripts.

Majuscule writing

Capital writing

The Latin alphabet first appears in the epigraphic type of majuscule writing, known as capitals. These characters form the main stem from which developed all the branches of Latin writing. On the oldest monuments (the inscriptiones bello Hannibalico antiquiores of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum = CIL), it is far from showing the orderly regularity of the later period. Side by side with upright and square characters are angular and sloping forms, sometimes very distorted, which seem to indicate the existence of an early cursive writing from which they would have been borrowed. Certain literary texts clearly allude to such a hand. Later, the characters of the cursive type were progressively eliminated from formal inscriptions, and capital writing reached its perfection in the Augustan Age.

Epigraphists divide the numerous inscriptions of this period into two quite distinct classes: tituli, or formal inscriptions engraved on stone in elegant and regular capitals, and acta, or legal texts, documents, etc., generally engraved on bronze in cramped and careless capitals. Palaeography inherits both these types. Reproduced by scribes on papyrus or parchment, the elegant characters of the inscriptions become the square capitals of the manuscripts, and the actuaria, as the writing of the acta is called, becomes the rustic capital.

Of the many books written in square capitals, the éditions de luxe of ancient times, only a few fragments have survived, the most famous being pages from manuscripts of Virgil. The finest examples of rustic capitals, the use of which is attested by papyri of the 1st century, are to be found in manuscripts of Virgil and Terence. Neither of these forms of capital writing offers any difficulty in reading, except that no space is left between the words. Their dates are still uncertain, in spite of attempts to determine them by minute observation.

The rustic capitals, more practical than the square forms, soon came into general use. This was the standard form of writing, so far as books are concerned, until the 5th century, when it was replaced by a new type, the uncial, which is discussed below.

Early cursive writing

While the set book-hand, in square or rustic capitals, was used for the copying of books, the writing of everyday life, letters and documents of all kinds, was in a cursive form, the oldest examples of which are provided by the graffiti on walls at Pompeii (CIL, iv), a series of waxen tablets, also discovered at Pompeii (CIL, iv, supplement), a similar series found at Verespatak in Transylvania (CIL, iii) and a number of papyri. From a study of a number of documents which exhibit transitional forms, it appears that this cursive was originally simplified capital writing. The evolution was so rapid, however, that at quite an early date the scriptura epistolaris of the Roman world can no longer be described as capitals. By the 1st century, this kind of writing began to develop the principal characteristics of two new types: the uncial and the minuscule cursive. With the coming into use of writing surfaces which were smooth, or offered little resistance, the unhampered haste of the writer altered the shape, size and position of the letters. In the earliest specimens of writing on wax, plaster or papyrus, there appears a tendency to represent several straight strokes by a single curve. The cursive writing thus foreshadows the specifically uncial forms. The same specimens show great inequality in the height of the letters; the main strokes are prolonged upwards (![]() = ⟨b⟩;

= ⟨b⟩; ![]() = ⟨d⟩) or downwards (

= ⟨d⟩) or downwards (![]() = ⟨q⟩;

= ⟨q⟩; ![]() = 's). In this direction, the cursive tends to become a minuscule hand.

= 's). In this direction, the cursive tends to become a minuscule hand.

Uncial writing

Although the characteristic forms of the uncial type appear to have their origin in the early cursive, the two hands are nevertheless quite distinct. The uncial is a libraria, closely related to the capital writing, from which it differs only in the rounding off of the angles of certain letters, principally ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . It represents a compromise between the beauty and legibility of the capitals and the rapidity of the cursive, and is clearly an artificial product. It was certainly in existence by the latter part of the 4th century, for a number of manuscripts of that date are written in perfect uncial hands (Exempla, pl. XX). It presently supplanted the capitals and appears in numerous manuscripts which have survived from the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, when it was at its height. By this time it had become an imitative hand, in which there was generally no room for spontaneous development. It remained noticeably uniform over a long period. It is difficult therefore to date the manuscripts by palaeographical criteria alone. The most that can be done is to classify them by centuries, on the strength of tenuous data. The earliest uncial writing is easily distinguished by its simple and monumental character from the later hands, which become progressively stiff and affected.

. It represents a compromise between the beauty and legibility of the capitals and the rapidity of the cursive, and is clearly an artificial product. It was certainly in existence by the latter part of the 4th century, for a number of manuscripts of that date are written in perfect uncial hands (Exempla, pl. XX). It presently supplanted the capitals and appears in numerous manuscripts which have survived from the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, when it was at its height. By this time it had become an imitative hand, in which there was generally no room for spontaneous development. It remained noticeably uniform over a long period. It is difficult therefore to date the manuscripts by palaeographical criteria alone. The most that can be done is to classify them by centuries, on the strength of tenuous data. The earliest uncial writing is easily distinguished by its simple and monumental character from the later hands, which become progressively stiff and affected.

List of Latin alphabets

Minuscule cursive writing

Early minuscule cursive

In the ancient cursive writing, from the 1st century onward, there are symptoms of transformation in the form of certain letters, the shape and proportions of which correspond more closely to the definition of minuscule writing than to that of majuscule. Rare and irregular at first, they gradually become more numerous and more constant and by degrees supplant the majuscule forms, so that in the history of the Roman cursive there is no precise boundary between the majuscule and minuscule periods.

The oldest example of minuscule cursive writing that has been discovered is a letter on papyrus, found in Egypt, dating from the 4th century. This marks a highly important date in the history of Latin writing, for with only one known exception, not yet adequately explained—two fragments of imperial rescripts of the 5th century—the minuscule cursive was consequently the only scriptura epistolaris of the Roman world. The ensuing succession of documents show a continuous improvement in this form of writing, characterised by the boldness of the strokes and by the elimination of the last lingering majuscule forms. The Ravenna deeds of the 5th and 6th centuries exhibit this hand at its perfection.

At this period, the minuscule cursive made its appearance as a book hand, first as marginal notes, and later for the complete books themselves. The only difference between the book-hand and that used for documents is that the principal strokes are shorter and the characters thicker. This form of the hand is usually called semi-cursive.

National hands

The fall of the Empire and the establishment of the barbarians within its former boundaries did not interrupt the use of the Roman minuscule cursive hand, which was adopted by the newcomers. But for gaps of over a century in the chronological series of documents which have been preserved, it would be possible to follow the evolution of the Roman cursive into the so-called "national hands", forms of minuscule writing which flourished after the barbarian invasions in Italy, France, Spain, England and Ireland, and which are still known as Lombardic, Merovingian, Visigothic, Anglo-Saxon and Irish. These names came into use at a time when the various national hands were believed to have been invented by the peoples who used them, but their connotation is merely geographical. Nevertheless, in spite of a close resemblance which betrays their common origin, these hands are specifically different, perhaps because the Roman cursive was developed by each nation in accordance with its artistic tradition.

- Lombardic writing

In Italy, after the close of the Roman and Byzantine periods, the writing is known as Lombardic, a generic term which comprises several local varieties. These may be classified under four principal types: two for the scriptura epistolaris, the old Italian cursive and the papal chancery hand, or littera romana, and two for the libraria, the old Italian book-hand and Lombardic in the narrow sense, sometimes known as Beneventana because it flourished in the principality of Benevento.

The oldest preserved documents written in the old Italian cursive show all the essential characteristics of the Roman cursive of the 6th century. In northern Italy, this hand began in the 9th century to be influenced by a minuscule book-hand which developed, as will be seen later, in the time of Charlemagne; under this influence it gradually disappeared, and ceased to exist in the course of the 12th century. In southern Italy, it persisted far on into the later Middle Ages. The papal chancery hand, a variety of Lombardic peculiar to the vicinity of Rome and principally used in papal documents, is distinguished by the formation of the letters a, e, q, t. It is formal in appearance at first, but is gradually simplified, under the influence of the Carolingian minuscule, which finally prevailed in the bulls of Honorius II (1124–1130). The notaries public in Rome continued to use the papal chancery hand until the beginning of the 13th century. The old Italian book-hand is simply a semi-cursive of the type already described as in use in the 6th century. The principal examples are derived from scriptoria in northern Italy, where it was displaced by the Carolingian minuscule during the 9th century. In southern Italy, this hand persisted, developing into a calligraphic form of writing, and in the 10th century took on a very artistic angular appearance. The Exultet rolls provide the finest examples. In the 9th century, it was introduced in Dalmatia by the Benedictine monks and developed there, as in Apulia, on the basis of the archetype, culminating in a rounded Beneventana known as the Bari type.

- Merovingian

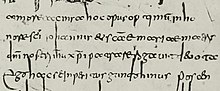

The offshoot of the Roman cursive which developed in Gaul under the first dynasty of kings is called Merovingian writing. It is represented by thirty-eight royal diplomas, a number of private charters and the authenticating documents of relics.

Though less than a century intervenes between the Ravenna cursive and the oldest extant Merovingian document (AD 625), there is a great difference in appearance between the two writings. The facile flow of the former is replaced by a cramped style, in which the natural slope to the right gives way to an upright hand, and the letters, instead of being fully outlined, are compressed to such an extent that they modify the shape of other letters. Copyists of books used a cursive similar to that found in documents, except that the strokes are thicker, the forms more regular, and the heads and tails shorter. The Merovingian cursive as used in books underwent simplification in some localities, undoubtedly through the influence of the minuscule book-hand of the period. The two principal centres of this reform were Luxeuil and Corbie.

- Visigothic

In Spain, after the Visigothic conquest, the Roman cursive gradually developed special characteristics. Some documents attributed to the 7th century display a transitional hand with straggling and rather uncouth forms. The distinctive features of Visigothic writing, the most noticeable of which is certainly the q-shaped ⟨g⟩, did not appear until later, in the book-hand. The book-hand became set at an early date. In the 8th century it appears as a sort of semi-cursive; the earliest example of certain date is ms lxxxix in the Capitular Library in Verona. From the 9th century the calligraphic forms become broader and more rounded until the 11th century, when they become slender and angular. The Visigothic minuscule appears in a cursive form in documents about the middle of the 9th century, and in the course of time grows more intricate and consequently less legible. It soon came into competition with the Carolingian minuscule, which supplanted it as a result of the presence in Spain of French elements such as Cluniac monks and warriors engaged in the campaign against the Moors.

The Irish and Anglo-Saxon hands, which were not directly derived from the Roman minuscule cursive, will be discussed in a separate sub-section below.

Set minuscule writing

One by one, the national minuscule cursive hands were replaced by a set minuscule hand which has already been mentioned and its origins may now be traced from the beginning.

Half-uncial writing

The early cursive was the medium in which the minuscule forms were gradually evolved from the corresponding majuscule forms. Minuscule writing was therefore cursive in its inception. As the minuscule letters made their appearance in the cursive writing of documents, they were adopted and given calligraphic form by the copyists of literary texts, so that the set minuscule alphabet was constituted gradually, letter by letter, following the development of the minuscule cursive. Just as some documents written in the early cursive show a mixture of majuscule and minuscule forms, so certain literary papyri of the 3rd century, and inscriptions on stone of the 4th century yield examples of a mixed set hand, with minuscule forms side by side with capital and uncial letters. The number of minuscule forms increases steadily in texts written in the mixed hand, and especially in marginal notes, until by the end of the 5th century the majuscule forms have almost entirely disappeared in some manuscripts. This quasi-minuscule writing, known as the "half-uncial" thus derives from a long line of mixed hands which, in a synoptic chart of Latin scripts, would appear close to the oldest librariae, and between them and the epistolaris (cursive), from which its characteristic forms were successively derived. It had a considerable influence on the continental scriptura libraria of the 7th and 8th centuries.

Irish and Anglo-Saxon writing

The half-uncial hand was introduced in Ireland along with Latin culture in the 5th century by priests and laymen from Gaul, fleeing before the barbarian invasions. It was adopted there to the exclusion of the cursive, and soon took on a distinct character. There are two well established classes of Irish writing as early as the 7th century: a large round half-uncial hand, in which certain majuscule forms frequently appear, and a pointed hand, which becomes more cursive and more genuinely minuscule. The latter developed out of the former. One of the distinguishing marks of manuscripts of Irish origin is to be found in the initial letters, which are ornamented by interlacing, animal forms, or a frame of red dots. The most certain evidence, however, is provided by the system of abbreviations and by the combined square and cuneiform appearance of the minuscule at the height of its development. The two types of Irish writing were introduced in the north of Great Britain by the monks, and were soon adopted by the Anglo-Saxons, being so exactly copied that it is sometimes difficult to determine the origin of an example. Gradually, however, the Anglo-Saxon writing developed a distinct style, and even local types, which were superseded after the Norman conquest by the Carolingian minuscule. Through St Columbanus and his followers, Irish writing spread to the continent, and manuscripts were written in the Irish hand in the monasteries of Bobbio Abbey and St Gall during the 7th and 8th centuries.

Pre-Caroline

James J. John points out that the disappearance of imperial authority around the end of the 5th century in most of the Latin-speaking half of the Roman Empire does not entail the disappearance of the Latin scripts, but rather introduced conditions that would allow the various provinces of the West gradually to drift apart in their writing habits, a process that began around the 7th century.

Pope Gregory I (Gregory the Great, d. 604) was influential in the spread of Christianity to Britain and also sent Queens Theodelinde and Brunhilda, as well as Spanish bishops, copies of manuscripts. Furthermore, he sent the Roman monk Augustine of Canterbury to Britain on a missionary journey, on which Augustine may have brought manuscripts. Although Italy's dominance as a centre of manuscript production began to decline, especially after the Gothic War (535–554) and the invasions by the Lombards, its manuscripts—and more important, the scripts in which they were written—were distributed across Europe.

From the 6th through the 8th centuries, a number of so-called 'national hands' were developed throughout the Latin-speaking areas of the former Roman Empire. By the late 6th century Irish scribes had begun transforming Roman scripts into Insular minuscule and majuscule scripts. A series of transformations, for book purposes, of the cursive documentary script that had grown out of the later Roman cursive would get under way in France by the mid-7th century. In Spain half-uncial and cursive would both be transformed into a new script, the Visigothic minuscule, no later than the early 8th century.

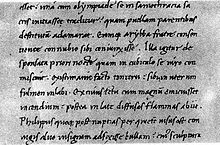

Carolingian minuscule

Beginning in the 8th century, as Charlemagne began to consolidate power over a large area of western Europe, scribes developed a minuscule script (Caroline minuscule) that effectively became the standard script for manuscripts from the 9th to the 11th centuries. The origin of this hand is much disputed. This is due to the confusion which prevailed before the Carolingian period in the libraria in France, Italy and Germany as a result of the competition between the cursive and the set hands. In addition to the calligraphic uncial and half-uncial writings, which were imitative forms, little used and consequently without much vitality, and the minuscule cursive, which was the most natural hand, there were innumerable varieties of mixed writing derived from the influence of these hands on each other. In some, the uncial or half-uncial forms were preserved with little or no modification, but the influence of the cursive is shown by the freedom of the strokes; these are known as rustic, semi-cursive or cursive uncial or half-uncial hands. Conversely, the cursive was sometimes affected, in varying degrees, by the set librariae; the cursive of the epistolaris became a semi-cursive when adopted as a libraria. Nor is this all. Apart from these reciprocal influences affecting the movement of the hand across the page, there were morphological influences at work, letters being borrowed from one alphabet for another. This led to compromises of all sorts and of infinite variety between the uncial and half-uncial and the cursive. It will readily be understood that the origin of the Carolingian minuscule, which must be sought in this tangle of pre-Carolingian hands, involves disagreement. The new writing is admittedly much more closely related to the epistolaris than the primitive minuscule; this is shown by certain forms, such as the open ⟨a⟩ (![]() ), which recall the cursive, by the joining of certain letters, and by the clubbing of the tall letters b d h l, which resulted from a cursive ductus. Most palaeographers agree in assigning the new hand the place shown in the following table:

), which recall the cursive, by the joining of certain letters, and by the clubbing of the tall letters b d h l, which resulted from a cursive ductus. Most palaeographers agree in assigning the new hand the place shown in the following table:

| Epistolaris | Librariæ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minuscule cursive | Capitals Uncials |

Half-uncial | Rustic uncial and half-uncial |

Pre-Carolingian Carolingian |

Semi-cursive |

Controversy turns on the question whether the Carolingian minuscule is the primitive minuscule as modified by the influence of the cursive or a cursive based on the primitive minuscule. Its place of origin is also uncertain: Rome, the Palatine school, Tours, Reims, Metz, Saint-Denis and Corbie have been suggested, but no agreement has been reached. In any case, the appearance of the new hand is a turning point in the history of culture. So far as Latin writing is concerned, it marks the dawn of modern times.

Gothic minuscule

In the 12th century, Carolingian minuscule underwent a change in its appearance and adopted bold and broken Gothic letter-forms. This style remained predominant, with some regional variants, until the 15th century, when the Renaissance humanistic scripts revived a version of Carolingian minuscule. It then spread from the Italian Renaissance all over Europe.

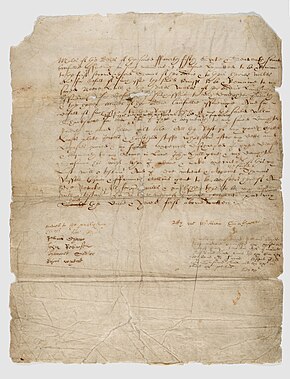

Rise of modern writing

These humanistic scripts are the base for the antiqua and the handwriting forms in western and southern Europe. In Germany and Austria, the Kurrentschrift was rooted in the cursive handwriting of the later Middle Ages. With the name of the calligrapher Ludwig Sütterlin, this handwriting counterpart to the blackletter typefaces was abolished by Hitler in 1941. After World War II, it was taught as an alternative script in some areas until the 1970s; it is no longer taught. Secretary hand is an informal business hand of the Renaissance.

Developments

There are undeniable points of contact between architecture and palaeography, and in both it is possible to distinguish a Romanesque and a Gothic period . The creative effort which began in the post-Carolingian period culminated at the beginning of the 12th century in a calligraphy and an architecture which, though still somewhat awkward, showed unmistakable signs of power and experience, and at the end of that century and in the first half of the 13th both arts reached their climax and made their boldest flights.

The topography of later medieval writing is still being studied; national varieties can, of course, be identified but the problem of distinguishing features becomes complicated as a result of the development of international relations, and the migration of clerks from one end of Europe to the other. During the later centuries of the Middle Ages the Gothic minuscule continued to improve within the restricted circle of de luxe editions and ceremonial documents. In common use, it degenerated into a cursive which became more and more intricate, full of superfluous strokes and complicated by abbreviations.

In the first quarter of the 15th century an innovation took place which exercised a decisive influence on the evolution of writing in Europe. The Italian humanists were struck by the eminent legibility of the manuscripts, written in the improved Carolingian minuscule of the 10th and 11th centuries, in which they discovered the works of ancient authors, and carefully imitated the old writing. In Petrarch's compact book hand, the wider leading and reduced compression and round curves are early manifestations of the reaction against the crabbed Gothic secretarial minuscule we know today as "blackletter".

Petrarch was one of the few medieval authors to have written at any length on the handwriting of his time; in his essay on the subject, La scrittura he criticized the current scholastic hand, with its laboured strokes (artificiosis litterarum tractibus) and exuberant (luxurians) letter-forms amusing the eye from a distance, but fatiguing on closer exposure, as if written for other purpose than to be read. For Petrarch the gothic hand violated three principles: writing, he said, should be simple (castigata), clear (clara) and orthographically correct. Boccaccio was a great admirer of Petrarch; from Boccaccio's immediate circle this post-Petrarchan "semi-gothic" revised hand spread to literati in Florence, Lombardy and the Veneto.

A more thorough reform of handwriting than the Petrarchan compromise was in the offing. The generator of the new style (illustration) was Poggio Bracciolini, a tireless pursuer of ancient manuscripts, who developed the new humanist script in the first decade of the 15th century. The Florentine bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci recalled later in the century that Poggio had been a very fine calligrapher of lettera antica and had transcribed texts to support himself—presumably, as Martin Davies points out— before he went to Rome in 1403 to begin his career in the papal curia. Berthold Ullman identifies the watershed moment in the development of the new humanistic hand as the youthful Poggio's transcription of Cicero's Epistles to Atticus.

By the time the Medici library was catalogued in 1418, almost half the manuscripts were noted as in the lettera antica. The new script was embraced and developed by the Florentine humanists and educators Niccolò de' Niccoli and Coluccio Salutati. The papal chancery adopted the new fashion for some purposes, and thus contributed to its diffusion throughout Christendom. The printers played a still more significant part in establishing this form of writing by using it, from the year 1465, as the basis for their types.

The humanistic minuscule soon gave rise to a sloping cursive hand, known as the Italian, which was also taken up by printers in search of novelty and thus became the italic type. In consequence, the Italian hand became widely used, and in the 16th century began to compete with the Gothic cursive. In the 17th century, writing masters were divided between the two schools, and there was in addition a whole series of compromises. The Gothic characters gradually disappeared, except a few that survived in Germany. The Italian became universally used, brought to perfection in more recent times by English calligraphers.

See also

- Asemic writing

- Authorship analysis

- Bastarda

- Blackletter

- Book hand

- Calligraphy

- Chancery hand

- Codicology

- Court hand

- Cursive

- Fragmentology (manuscripts)

- Victor Gardthausen – palaeographer

- Glyph and Grapheme

- Graffiti

- Hand (writing style)

- Handwriting

- Historical Documents

- History of writing

- Isogloss

- Italic script

- Law hand

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- Palaeographic letters

- Penmanship

- Philology

- Recension

- Ronde script (calligraphy)

- Rotunda (script)

- Round hand

- Scribal abbreviation

- Secretary hand

- Textual scholarship

References

- Cardenio, Or, the Second Maiden's Tragedy, pp. 131–3: By William Shakespeare, Charles Hamilton, John Fletcher (Glenbridge Publishing Ltd., 1994) ISBN 0-944435-24-6

- "palaeography". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Latin Palaeography Network". Civiceducationproject.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Jean Mabillon" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Bernard de Montfaucon et al., Palaeographia Graeca, sive, De ortu et progressu literarum graecarum, Paris, Ludovicum Guerin (1708); André Vauchez, Richard Barrie Dobson, Adrian Walford, Michael Lapidge, Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages (Routledge, 2000), Volume 2, p. 1070

- Urry, William G.. "paleography". Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 Aug. 2013. Accessed 15 November 2023.

- Robert P. Gwinn, "Paleography" in the Encyclopædia Britannica, Micropædia, Vol. IX, 1986, p. 78.

- Fernando De Lasala, Exercise of Latin Paleography (Gregorian University of Rome, 2006) p. 7.

- Turner, Eric G. (1987). Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (2nd ed.). London: Institute of Classical Studies.

- ^ Nongbri, Brent (2005). "The Use and Abuse of P52: Papyrological Pitfalls in the Dating of the Fourth Gospel" (PDF). Harvard Theological Review. 98: 23–48 (24). doi:10.1017/S0017816005000842. S2CID 163128006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Griffin, Bruce W. (1996), "The Paleographical Dating of P-46"

- Schniedewind, William M. (2005). "Problems of Paleographic Dating of Inscriptions". In Levy, Thomas; Higham, Thomas (eds.). The Bible and Radiocarbon Dating: Archaeology, Text and Science. Routledge. ISBN 1-84553-057-8.

- ^ Cf. Klaus Beyer, The Aramaic Language, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986, pp. 9- 15; Rainer Degen, Altaramäische Grammatik der Inschriften des 10-8 Jh.v.Chr., Wiesbaden, repr. 1978.

- This script was also used during the reign of King Ashoka in his edicts to spread early Buddhism. Cf. "Ancient Scripts: Aramaic". Accessed 05/04/2013

- Cf. Noël Aimé-Giron, Textes araméens d’Égypte, Cairo, 1931 (Nos. 1–112); G.R. Driver, Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B.C., Oxford: Clarendon Press, repr. 1968; J.M. Lindenberger Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Aramaic Proverbs of Ahiqar, Baltimore, 1983.

- Cf. E. H. Minns, Journ. of Hell. Stud., xxxv, pp.22ff.

- Cf. New Pal. Soc., ii, p. 156.

- ^ In creating and expanding the following sections on Greek palaeography—inclusive of the "Vellum and Paper Manuscripts" subsection—specialist sources have been consulted and thoroughly perused for the relevant text and citations, as follows: primarily the article on general palaeography by renowned British papyrologist and scholar Harold Idris Bell, present in Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Palaeography § Greek Writing" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 556–579 see pages 557 to 567.; Barry B. Powell, Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization, Oxford: Blackwell, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4051-6256-2; Jack Goody, The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society, Cambridge University Press, 1986; the essential work by British palaeographer Edward Maunde Thompson, An Introduction to Greek and Latin Palaeography, Cambridge University Press, 1912 (repr. 2013). ISBN 978-1-108-06181-0; the German work by Bernhard Bischoff, Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, trad. Daibhm O. Cróinin & David Ganz, Cambridge University Press, 1990, esp. Part A "Codicology", pp. 7–37. ISBN 978-0-521-36726-4. These texts will be referred to throughout the present article with relevant inline citations.

- Fragments of Timotheus' poetry survive, published in T. Bergk, Poetae lyrici graeci. The cit. papyrus-fragment of his Persae (Persians) was discovered at Abusir and has been edited by Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Der Timotheos-Papyrus gefunden bei Abusir am 1. Februar 1902, Leipzig: Hinrichs (1903), with content discussion. Cf. V. Strazzulla, Persiani di Eschilo ed il nomo di Timoteo (1904); S. Sudhaus in Rhein. Mus., iviii. (1903), p. 481; and T. Reinach and M. Croiset in Revue des etudes grecques, xvi. (1903), pp. 62, 323.

- Wax tablets of this period are preserved at the University College London, cf. Speaking in the Wax Tablets of Memory, Agocs, PA (2013). In: Castagnoli, L. and Ceccarelli, P, (eds.), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Cf. Campbell, Lewis (1891). "On the Text of the Papyrus Fragment of the Phaedo". Classical Review. 5 (10): 454–457. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00179582. S2CID 162051928.

- Cf. Wilhelm Schubart, Griechische Palaeographie, C.H. Beck, 1925, vol. i, pt. 4; also 1st half of new ed. of Muller's Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft; and Schubart's Das Buch bei den Griechen und Römern (2nd ed.); ibid., Papyri Graecae Berolinenses (Boon, 1921).

- Cf. P.F. de' Cavalieri & J. Lietzmann, Specimina Codicum Graecorum Vaticanorum No. 5, Bonn, 1910; G. Vitelli & C. Paoli, Collezione fiorentina di facsimili paleografici, Florence (rist. 1997).

- Cf. T.W. Allen, "Notes on Abbreviations in Greek Manuscripts", Joun. Hell. Stud., xl, pp. 1–12.

- Falk, Harry (1993). Schrift im alten Indien: ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen. Tübingen: G. Narr. ISBN 3823342711. OCLC 29443654.

- Salomon, Richard (1995). "Review: On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- There are few available texts relating to "Indian palaeography", among which Ahmad Hasan Dani, Indian Palaeography, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1997; A. C. Burnell, Elements of South-Indian Palaeography, from the Fourth to the Seventeenth Century AD, repr. 2012; Rajbali Pandey, Indian Palaeography, Motilal Banarasi Das, 1957; Naresh Prasad Rastogi, Origin of Brahmi Script: The Beginning of Alphabet in India, Chowkhamba Saraswatibhawan, 1980.