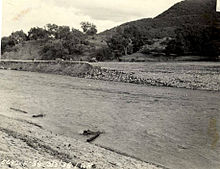

The Los Angeles River overflowing its banks near Griffith Park The Los Angeles River overflowing its banks near Griffith Park | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Duration | February–March 1938 |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 113-115 |

| Damage | About US$78 million ($1.69 billion in 2023 dollars) 5,601 buildings destroyed 1,500 buildings damaged several small towns completely destroyed Large portions of Riverside and Orange counties completely inundated |

| Areas affected | Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties, California |

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of California |

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

The Los Angeles flood of 1938 was one of the largest floods in the history of Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside Counties in southern California. The flood was caused by two Pacific storms that swept across the Los Angeles Basin in February-March 1938 and generated almost one year's worth of precipitation in just a few days. Between 113–115 people were killed by the flooding. The Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana Rivers burst their banks, inundating much of the coastal plain, the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys, and the Inland Empire. Flood control structures spared parts of Los Angeles County from destruction, while Orange and Riverside Counties experienced more damage.

The flood of 1938 is considered a 50-year flood. It caused $78 million of damage ($1.69 billion in 2023 dollars), making it one of the costliest natural disasters in Los Angeles' history. In response to the floods, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other agencies began to channelize local streams in concrete, and built many new flood control dams and debris basins. These works have been instrumental in protecting Southern California from subsequent flooding events, such as in 1969 and 2005, which both had a larger volume than the 1938 flood.

Background

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Due to its location between the Pacific Ocean and the high San Gabriel Mountains, the Los Angeles Basin is subject to flash floods caused by heavy orographic precipitation from Pacific storms hitting the mountains. Due to the arid climate, soils are too hard to absorb water quickly during storm events, resulting in large amounts of surface runoff. The steep, rocky terrain of the San Gabriel Mountains further contributes to the rapid runoff and resultant flooding hazard.

Between February 27 and 28, 1938, a storm from the Pacific Ocean moved inland into the Los Angeles Basin, running eastward into the San Gabriel Mountains. The area received almost constant rain totaling 4.4 in (110 mm) from February 27-March 1. This caused minor flooding that affected only a few buildings in isolated canyons and some low-lying areas along rivers. Fifteen hours later on March 1, at approximately 8:45 PM, a second storm hit the area, creating gale-force winds along the coast and pouring down even more rain. The storm brought rainfall totals to 10 in (250 mm) in the lowlands and upwards of 32 in (810 mm) in the mountains. When the storm ended on March 3, the resulting damage was horrific.

Effects

The 1938 flood destroyed 5,601 homes and businesses and damaged a further 1,500 properties. The flooding was accompanied by massive debris flows of mud, boulders, and downed trees, which surged out of the foothill canyons. Transport and communication were cut off for many days as roads and railroads were buried, and power, gas, and communication lines were cut. Dozens of bridges were destroyed by the sheer erosive force of floodwaters or by the collision of floating buildings and other wreckage. Some communities were buried as much as 6 feet (1.8 m) deep in sand and sediment, requiring a massive cleanup effort afterward. It took from two days to a week to restore highway service to most impacted areas. The Pacific Electric rail system, serving Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, and Riverside Counties, was out of service for three weeks.

Although the 1938 flood caused the most damage of any flood in the history of Los Angeles, the rainfall and river peaks were not even close to the Great Flood of 1862, the largest known flood by total volume of water. However, during the 1862 flood, the region was much less populated than it was in 1938.

Los Angeles area

About 108,000 acres (44,000 ha) were flooded in Los Angeles County, with the worst hit area being the San Fernando Valley, where many communities had been built during the economic boom of the 1920s in low-lying areas once used for agriculture. In fact, many properties were located in old river beds that had not seen flooding in some years. Swollen by its flooded tributaries, the Los Angeles River reached a maximum flood stage of about 99,000 cubic feet per second (2,800 m/s). The water surged south, inundating Compton before reaching Long Beach, where a bridge at the mouth of the river collapsed killing ten people. To the west, Venice and other coastal communities were flooded with the overflow of Ballona Creek. The Los Angeles Times chartered a United Air Lines Mainliner to provide them an aerial view of flooding damage. The reporter remarked: "Disaster, gutted farmlands, ruined roads, shattered communications, wrecked railroad lines—all leap into sharp-etched reality from that altitude."

Communities and mining operations in the San Gabriel Mountains such as Camp Baldy were destroyed, stranding hundreds of people for days. As many as 25 buildings were destroyed in the Arroyo Seco canyon, although due to a successful evacuation, no one was killed. Two Civilian Conservation Corps camps, three guard stations and a ranger station were destroyed, along with 60 campgrounds. Almost every road and trail leading into the Angeles National Forest was damaged or destroyed by erosion and landslides. About 190 men had to be evacuated from one of the CCC camps, near Vogel Flats, using a cable strung across Big Tujunga Canyon.

The Tujunga Wash reached its peak flow on March 3, with a water flow of an estimated 54,000 cubic feet per second (1,500 m/s). Upper Big Tujunga Canyon was "all but swept clean of structures that were not up above the flood line". In the San Fernando Valley, the floodwaters swept through many areas after escaping the normal channels of Tujunga Creek and its tributaries. Waters reached deep into the valley; the Pacoima Wash flooded Van Nuys. Five people died when the Lankershim Boulevard bridge collapsed at Universal City, just below the confluence of Tujunga Wash and the LA River. The flooding would have been much worse had a large debris flow not been halted at Big Tujunga Dam. Sam Browne, dam keeper during the 1938 flood, wrote that "Large oak trees several hundred years old rushed down the canyon like kindling... If this dam had never been built, there is no telling what would have happened to Sunland, and the city of Tujunga and the northern end of Glendale."

San Gabriel Valley

On the San Gabriel River, dams built prior to 1938 greatly reduced the magnitude of flooding. Along the West Fork the floodwaters first hit Cogswell Dam, which had been completed just four years earlier in 1934. Cogswell moderately reduced the flood crest on the West Fork, which further downstream joined with the undammed East Fork to peak at more than 100,000 cu ft/s (2,800 m/s). The floodwaters poured into the reservoir of the still incomplete San Gabriel Dam, filling it over the night of March 2-3 and overtopping the emergency spillway. The maximum release from San Gabriel was held at 60,000 cu ft/s (1,700 m/s), while the downstream Morris Dam further reduced the peak, to about 30,000 cu ft/s (850 m/s). As a result, much of the San Gabriel Valley were spared from flooding, although heavy damage still occurred in some areas. In Azusa, four spans of the 1907 "Great Bridge" along the Monrovia–Glendora Pacific Electric line, which had survived the San Gabriel's seasonal flooding for over 30 years, were swept away in the torrent.

Along the East Fork of the San Gabriel River, flooding obliterated much of a new highway that was intended to connect the San Gabriel Valley to Wrightwood. The southern stub of the highway has been rebuilt as today's East Fork Road, but north of Heaton Flat little remains except for the Bridge to Nowhere, a 120-foot (37 m) tall arch bridge that was saved due to its height above the floodwaters. Located about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the nearest road, the bridge is now a popular destination for hikers and bungee jumpers.

Riverside and Orange Counties

In Riverside and Orange Counties, the Santa Ana River reached a peak flow of about 100,000 cubic feet per second (2,800 m/s), completely overwhelming the surrounding dikes and transforming low-lying parts of Riverside County and Orange County into huge, shallow lakes. A reporter for the Los Angeles Times described the river as "swollen crazy-mad". Forty-three people were killed in Atwood and La Jolla in Placentia. Flooding in the city of Riverside took another 15 lives. The cities of Anaheim and Santa Ana in Orange County were flooded up to 6 feet (1.8 m) deep for several weeks.

High Desert

Although most of the damage occurred on the windward (southwestern) side of the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains, large amounts of rain also fell on the northeast side which drains to the Mojave Desert. The Little Rock Dam on Little Rock Creek overtopped during the flood due to a damaged spillway siphon that had been plugged by debris; hundreds of people in downstream Palmdale were evacuated. Further east, the Mojave River burst its banks, damaging long stretches of the ATSF railroad and causing damage in Victorville and Barstow. The main line between Barstow and Los Angeles was closed for a week. The Southern Pacific Railroad main line over Tehachapi Pass was closed for two weeks, requiring emergency service via buses and trucks. Structures in the Acton area were also lost as the banks of the Santa Clara River crumbled, during the flood on March 2, 1938.

Aftermath

Dams such as those at San Gabriel and Big Tujunga greatly reduced downstream damage in the 1938 flood. Many even larger dams were built after the flood to provide a greater degree of protection to downstream communities. Hansen Dam had already begun construction but stood incomplete during the 1938 flood and was unable to prevent the devastating flooding along Tujunga Wash. The dam was completed two years later, in 1940. The Sepulveda Dam was built in 1941 to prevent the Los Angeles River from flooding the lower San Fernando Valley, Burbank and Glendale.

Along the San Gabriel River, the Santa Fe Dam and Whittier Narrows Dam had both been proposed prior to 1938, but had little political support until the devastation of the 1938 flood, after which federal funds were made available for both dams. Santa Fe was completed in 1949, and Whittier Narrows in 1956. Construction was also expedited at Prado Dam, which had been planned in 1936 but work had not yet started at the time of the 1938 flood. Had Prado Dam been operational in 1938 it would likely have prevented the severe flooding in Orange County.

Although some river channel work was already in place at the time, the 1938 flood was the main impetus for channelizing the Los Angeles River in concrete, speeding the flow of floodwaters to the sea. The channelization project, authorized by the Flood Control Act of 1941, was undertaken by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers starting just a few years after the 1938 flood, with emergency funding from the federal government. About 278 miles (447 km) of streams in the Los Angeles River system were encased in concrete, a huge undertaking that took twenty years to complete. The system successfully protected Los Angeles from massive flooding in 1969. The San Gabriel and Santa Ana Rivers were also ultimately channelized to protect against future floods, although it took much longer for those projects to be completed.

In response to the large debris flows generated by the 1938 flood, the U.S. Forest Service was tasked with fire suppression in the Angeles Forest to reduce the risk of erosion in burned areas.

Appearances in media

- California Floods - Pathé News

See also

References

- ^ "Los Angeles Basin's 1938 Catastrophic Flood Event". Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ Romo, Rene (February 22, 1988). "Flood of Memories : Longtime Valley Residents Recall 1938 Deluge That Took 87 Lives, Did $78 Million in Damage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ "The History of the Los Angeles River". L.A. River Connection. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007.

- ^ Panhorst, F.W. (August 1938). "Role of Highways in Recent California Floods: Road Network Takes On Added Value in Time of Emergency". Civil Engineering. 8 (8). SCV History: 542–544. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Cram, Justin (February 28, 2012). "Los Angeles Flood of 1938: Cementing the River's Future". Departures. KCET. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (March 3, 2017). "The Southern California Deluge of 1938". KCET. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "USGS Gage #11103000 Los Angeles River at Long Beach, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1929–1992. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- “Plane trip shows scene of desolation.” In Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1938, pp. 1-2.

- ^ “Scores trapped in mountains: Pilots report canyon retreats destroyed or heavily damaged.” In Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1938, p. 7.

- ^ Cermak, Robert W. (2005). Fire in the Forest: A History of Forest Fire Control on the National Forests in California, 1898-1956. USDA Forest Service. p. 200. ISBN 1-59351-429-8.

- "USGS Gage #11097000 Big Tujunga Creek below Hansen Dam, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1933–2016. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Roderick, Kevin (October 20, 1999). "Deadly Flood of 1938 Left Its Mark on Southland". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Bartholomew, Dana (July 21, 2011). "Dam renovation expected to help cut water costs". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- “Small Losses prove value of dam system: Huge amounts of water stored and damage held to minimum” in Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1938, p. 7.

- Medina, Daniel (March 20, 2014). "The Other River that Defined L.A.: The San Gabriel River in the 20th Century". KCET. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "Los Angeles Raiders Football Stadium, Irwindale, Parking and Associated Facilities Development: Environmental Impact Statement, Volume 2". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 1988. p. 35. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Goran, David (June 2, 2016). "The Bridge to Nowhere – One of the most bizarre artifacts to be found deep in the San Gabriel Mountains". The Vintage News. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "USGS Gage #11074000 Santa Ana River below Prado Dam, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1938–2016. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Gold, Scott (October 3, 1999). "1938 Flood: A Watershed for the County". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- “Plane trip shows scene of desolation.” In Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1938, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (November 29, 2012). "The Santa Ana River: How It Shaped Orange County". KCET. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Elkind, Sarah S. (2011). How Local Politics Shape Federal Policy: Business, Power, and the Environment in Twentieth-century Los Angeles. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-80783-489-3.

- "History of the Santa Ana River" (PDF). Santa Ana River Vision Plan. City of Santa Ana. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "California Floods Aka Raging Torrents In California (1938)".

External links

- Image Gallery of 1962, 1941, 1938 Los Angeles floods

- 1938 Flood photos by Herman J. Schultheis at the Los Angeles Public Library

- 1930s floods in the United States

- 1930s floods

- 1938 in Los Angeles

- 1938 natural disasters in the United States

- February 1938 events in the United States

- March 1938 events in the United States

- Disasters in Los Angeles

- Floods in California

- Los Angeles River

- History of Los Angeles

- 20th century in Los Angeles County, California

- 20th century in Orange County, California

- Events in Riverside County, California