Prince Kromma Muen Thepphiphit (Thai: กรมหมื่นเทพพิพิธ) was a Siamese prince of the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty of the Ayutthaya kingdom. He is known for his colorful adventurous political career. Prince Thepphiphit led a failed rebellion in 1758 against his half-brother Ekkathat the last king of Ayutthaya. He was then exiled to Ceylon, which had been under the Kingdom of Kandy. In 1760, Sinhalese Sangha and nobility conspired to overthrow King Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy to place the Siamese prince Thepphiphit on the Kandyan throne but the plan was thwarted and Thepphiphit had to leave Ceylon. Prince Thepphiphit returned to Siam at Mergui, Tenasserim, in 1762. When the Burmese attacked and conquered Tenasserim in early 1765, Thepphiphit moved to Chanthaburi on Eastern Siamese coast. In 1766, he raised an army in Eastern Siam to fight the Burmese but was defeated. Thepphiphit fled to Nakhon Ratchasima in the northeast where he engaged in a local power struggle, ending up being held hostage at Phimai. At the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, local officials in the northeast declared Thepphiphit a ruler, becoming "Chao Phimai" or the Lord of Phimai as one of several regional regime leaders in aftermath of the collapse of Ayutthaya, entrenching himself at Phimai. In 1768, the new king Taksin of Thonburi kingdom marched to subjugate Thepphiphit's Phimai regime. Thepphiphit was then captured and deported to Thonburi, where he was eventually executed in November 1768.

Early life

Very few native Siamese records about the early life of Prince Thepphiphit survive. A Chinese source stated that, at his death in 1768, Prince Thepphiphit was around fifty years old so he should be born around 1718, in the reign of his uncle King Thaisa of Ayutthaya. Prince Thepphiphit, at his birth, was known as Khaektao ("parakeet") or Prince Phra Ong Chao Khaek (Thai: พระองค์เจ้าแขก) of the Phra Ong Chao rank. The Chinese source stated that Thepphiphit was an elder half-brother of Ekkathat, who was also born in 1718, while in Thai chronicles the order of the princes was given as Prince Thammathibet coming as the first one, Ekkathat as the second one and Thepphiphit as the third one. Thepphiphit should be nearly the same age as his half-brother Ekkathat.

Prince Thepphiphit, initially known as Prince Khaek, was a son of Prince Phon, who was the younger brother and Wangna or Uparat or heir presumptive to King Thaisa. He was born to an unnamed secondary consort of his father. According to the Chinese source, Thepphiphit's mother was of the Baitou race, suggesting Northern Thai or Lao ethnicity. Thepphiphit had a younger brother Prince Phra Ong Chao Pan (Thai: พระองค์เจ้าปาน) and a sister who shared the same mother. In 1732, King Thaisa became ill and Prince Phon, Thepphiphit's father, rallied armies in preparation for the upcoming succession conflict but was caught. Prince Phon, along with his sons and presumably Thepphiphit, ordained as Buddhist monks to avoid political repercussions. Next year, in 1733, King Thaisa died, and a succession war ensued in Ayutthaya between Prince Phon and his nephews, sons of Thaisa. Prince Phon eventually prevailed and ascended the Siamese throne as King Borommakot in 1733.

In efforts to contain future dynastic princely conflicts, King Borommakot assigned manpower regiments known as Kroms to his sons the royal princes to control the allocation of manpower among his sons. Prince Khaek was given the Krom title Kromma Muen Thepphiphit (Thai: กรมหมื่นเทพพิพิธ), while his brother Prince Pan became Kromma Muen Sepphakdi (Thai: กรมหมื่นเสพภักดี). Borommakot's sons were also ranked according to the status of their mothers. Thammathibet, Ekkathat and Uthumphon, who were born to Borommakot's two main queens, were given the superior rank of Kromma Khun. Other sons of Borommakot who were born to his secondary consorts, including Thepphiphit and his brother Sepphakdi, were given the inferior rank of Kromma Muen.

Princely Conflicts

Prince Thammathibet, eldest son of Borommakot born to a principal queen, was made Wangna Prince of the Front Palace and heir presumptive to Borommakot in 1741. The princes maintained uneasy share of power during the reign of their father. The seven royal princes were divided into two political camps. The first faction composed of primary sons of Borommakot including Thammathibet, Ekkathat and Uthumphon. The second faction composed of the secondary princes including Chitsunthorn, Sunthornthep and Sepphakdi (Thepphiphit's brother), known collectively as Chao Sam Krom (Thai: เจ้าสามกรม) or the Three Princes. Thepphiphit, despite being a secondary prince, seemed to be aligned with the faction of the superior princes. Death of Chaophraya Chamnan Borirak the chief minister in 1753 allowed Prince Thammathibet the royal heir to assert his powers. Prince Thammathibet was later found having adulterous relationship with a consort of his father Borommakot and was also found yearning for a sedition. Prince Thammathibet was whipped with rattan cane strokes and died from injuries in April 1756.

Death of Prince Thammathibet in 1756 left the position of royal heir vacant. It was this time that Prince Thepphiphit made his first political move. King Borommakot disfavored his second son Ekkathat for his supposed incompetency. Thepphiphit then led the proposal to the king in 1757, in concert with other high-ranking ministers of Chatusadom, to make Uthumphon the new heir. Uthumphon, as the youngest son of Borommakot, did not aspire for kingship but Borommakot preferred Uthumphon over Ekkathat, citing that Ekkathat would be sure to bring disaster to the kingdom. Uthumphon finally consented to the demands of his father Borommakot, who made Uthumphon the Prince of the Front Palace and heir presumptive in 1757 and also exiled Ekkathat to become a Buddhist monk in the northeastern outskirt of Ayutthaya to prevent Ekkathat from incurring any troubles. This event earned Thepphiphit a political favor as he was the one who proposed to Borommakot to elevate Uthumphon to the position.

In spite of these speculative arrangements, conflicts erupted between Uthumphon and the Three Princes who sought to claim the throne when Borommakot died in April 1758. Ekkathat returned from exile to assist Uthumphon in putting down the Three Princes. Ekkathat, Uthumphon and Thepphiphit unified and cooperated against the Three Princes. The Three Princes, including Thepphiphit's brother Sepphakdi, were eventually captured and executed in May 1758. Uthumphon triumphantly ascended the Ayutthayan throne in May, but Uthumphon faced political challenges from Ekkathat who laid his own claims to the throne. Uthumphon gave in and abdicated after merely ten days. Ekkathat ascended the throne as the last king of Ayutthaya in June 1758, while Uthumphon went to become a Buddhist monk at Wat Pradu temple, earning him the epithet Khun Luang Hawat or the King Who Sought Temple.

With the ascension of Ekkathat at the expense of Uthumphon, Thepphiphit felt threatened because he had been such a supporter of Uthumphon. After the enthronement ceremony of Ekkathat, Thepphiphit went out in June 1758 to be ordained as a Buddhist monk to avoid possible political retributions from Ekkathat, staying at Wat Krachom temple just off the northeastern corner of Ayutthaya citadel.

Rebellion of 1758

Upon his ascension to the throne, Ekkathat found few supports in the royal court, most of whom supported Uthumphon. Ekkathat brought his two brother-in-laws Pin and Chim to power in Siamese royal court. Pin and Chim were given immense powers. They upset and insulted high-ranking Chatusadom ministers. Those ministers, including Chaophraya Aphairacha the chief minister and Phraya Yommaraj the police chief, conspired to overthrow Ekkathat in favor of Uthumphon. In December 1758, those conspirators visited Prince Thepphiphit, who had been a Buddhist monk at Wat Krachom temple. Thepphiphit, despite being a Buddhist monk, was still very active in politics. Thepphiphit accepted this challenge. Thepphiphit and other conspirators visited Uthumphon at Wat Pradu temple, asking Uthumphon to consent to the plan. Uthumphon, who was unwilling to be involved in such seditious affair, gave a vague unpromising answer that was interpreted as favorable by Thepphiphit.

Uthumphon, however, decided not to trust Thepphiphit, given his ambitions. Uthumphon told Ekkathat about the upcoming rebellion in exchange for Ekkathat sparing the lives of the conspirators. The conspiring ministers Aphairacha, Yommaraj and others were arrested, punished, whipped with rattan canes and imprisoned for life but not executed. Thepphiphit himself fortified at Wat Krachom temple against Ekkathat. Thepphiphit's Chao Krom or Chief Servant managed to raise a number of supporters who vehemently and devotedly defended Thepphiphit. Ekkathat devised a plan to take down Thepphiphit without forces by declaring that the crime of sedition would be placed solely upon the Chao Krom or Thepphiphit's Chief Servant. The Chief Servant then deserted Thepphiphit along with his subordinates, leaving Thepphiphit exposed. Thepphiphit was left with no choices but to escape. Thepphiphit fled to the west where he was caught and apprehended at Phra Thaen Dong Rang in modern Tha Maka district, Kanchanaburi province.

Upholding the promise made to Uthumphon, Ekkathat would not execute Thepphiphit but rather exile him. Coincidentally, a Dutch ship happened to arrive in Ayutthaya to procure some Siamese Buddhist monks to Sri Lanka. Ekkathat then had Thepphiphit, still in Buddhist monk robes, along with his family, consorts and children, board on the Dutch ship across the Indian Ocean to be exiled to Ceylon or Sri Lanka in early 1759.

Conspiracy at Ceylon

Ascension of King Sri Vijaya Rajasinha, who was of Southern Indian Telugu Nayakkar origin, to the Sinhalese throne of Kandy in 1739, with the support of his mentor the Sinhalese Buddhist monk Weliwata Sri Saranankara, began the rule of Madurai Nayak dynasty over Ceylon. The Nayaks of South India were practitioners of Shaivite Hinduism rather than Sinhalese Theravada Buddhism. In the aftermath of repeated Portuguese and Dutch incursions, Theravada Buddhism in Ceylon had been in a deteriorated state without any properly ordained Bhikkhu monks left to maintain and continue the religion.

King Sri Vijaya Rajasinha died in 1751 and was succeeded by his brother-in-law Kirti Sri Rajasinha. The new king Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy, inspired by the monk Weliwata Saranankara, made efforts to rehabilitate Sinhalese Theravada by sending delegates to the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya, requesting for Siamese monk to revive the Upasampada ordinations and to reestablish Bhikkhu monastic order in Ceylon. King Borommakot of Ayutthaya responded by sending Siamese monks under Upali to Ceylon, arriving in 1753, leading to conception of the Siam Nikaya sect in Sri Lanka. The monk Weliwata Saranankara was ordained by the Siamese monks into this new 'Siamese sect'. Since then, Ayutthaya and Kandy had been maintaining religious relations, with Dutch ships serving as the conduit to regularly transport Siamese monks to Sri Lanka. Weliwata Saranankara was appointed by Kirti Sri Rajasinha in 1753 as the Sangharaja or Buddhist Hierophant in Sri Lanka. Despite these religious achievements, the powerful native Sinhalese monks, led by Weliwata Saranankara himself, were contemptuous at the king's association with Hinduism.

Thepphiphit arrived at Ceylon in 1759 in Buddhist monk robes on the Dutch ship along with his family. The Dutch source recorded Thepphiphit's monastic name as Tammebaan or Thammaban in Thai. The Sinhalese, who apparently did not know about the reason of Thepphiphit's arrival, provided Thepphiphit and his family with accommodation in Kandy. Arrival of Thepphiphit in Ceylon perhaps served as the catalyst for the imminent revolution against King Kirti Sri Rajasinha. Thepphiphit befriended a relative of the Sinhalese noble Sammanakodi the Udagampaha Adigar. In July 1760, the Sangharaja Weliwata Saranankara conspired with Adigar Sammanakodi and the monks of the Siamese sect, including the Siamese monks themselves, to overthrow the Nayakkar King Kirti Sri Rajasinha and put the Siamese prince Thepphiphit on the throne of Kandy. The conspirators, including Thepphiphit himself, held a secret meeting at a temple in Anuradhapura to conceive the plan. Thepphiphit then went to stay at Kehelella near Colombo, waiting for the signal.

In 1760, Adigar Sammanakodi invited King Kirti Sri Rajasinha for a Buddhist sermon in Siamese language at the Malwatta temple, the head temple of the Siamese sect where the Sangharaja monk Weliwata Saranankara resided. In the same time, a message in Thai language was sent to Thepphiphit but the message was intercepted and sent to Kirti Sri Rajasinha. The king actually went to listen to Buddhist sermons at Malwatta temple per invitation but the royal guards found the apparatus to assassinate the king – a coffin with protruding spikes and a platform above it. It was assumed that the plan was for Kirti Sri Rajasinha to sit on the platform during the sermon, in which the platform would collapse, the king would fall into the coffin and impaled to death by the spikes. Kirti Sri Rajasinha did not mount onto that sinister platform but instead stood to listen to the sermons and returned. Conspirators were soon arrested. Adigar Sammanakodi was executed, while the monk Weliwata Saranankara was imprisoned in Kehelella. Siamese monks were expelled to the Dutch-controlled area.

King Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy sent Thepphiphit and his family to the Dutch port of Trincomalee, asking the Dutch to deport the Siamese prince. Jan Schreuder the Dutch governor of Ceylon was reluctant to comply at first but when he learned about the incident Schreuder agreed to take Thepphiphit out of Ceylon. Thepphiphit and his family then left Ceylon with Dutch assistance, presumably on a Dutch ship from Trincomalee. Thepphiphit stayed at the Dutch port of Tuticorin in South India for a while. In May 1761, the Chinese Annals of Batavia or Kai Ba Lidai Shiji (開吧歷代史記) stated that 'a son of the king of Ceylon and his wife' arrived in Batavia, where they were ceremoniously received by Dutch East Indies Governor-General Petrus Albertus van der Parra in the Batavia Castle. This enigmatic princely figure from Ceylon should be Prince Thepphiphit, who took shelter at Batavia after his troubled departure from Ceylon. The Dutch governor-general provided Thepphiphit with residence in the Great Mauk.

Confinement in Tenasserim

Since the sixteenth century, Western powers the Portuguese and later the Dutch had taken control of all coastal lowlands of Ceylon, driving the indigenous power to the mountainous inland. After Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy had averted the assassination attempt upon himself in 1760, in the same year, the Sinhalese people on the coastal lowlands under Dutch rule rebelled against the Dutch governor Jan Schreuder of Ceylon. Next year, in 1761, King Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy took this opportunity to invade and conquer the coastal lowlands from Dutch Ceylon. Facing internal unrest and external incursion, Jan Schreuder was replaced as governor by Lubbert Jan van Eck in 1762.

One of the sons of Thepphiphit died during his journey from Ceylon back to Siam. Thepphiphit and his family returned to Siam at the Siamese port of Mergui in Tenasserim in 1762. King Ekkathat of Ayutthaya was shocked and furious at the return of Thepphiphit. Ekkathat sent a royal intendant to impose confinement on Thepphiphit at Tenasserim, not allowing Thepphiphit to return to Ayutthaya. Meanwhile, two sons of Thepphiphit were sent to live with Uthumphon the temple king at Wat Pradu temple in Ayutthaya as political hostages. His wife and daughter were also sent to Ayutthaya.

Lubbert Jan van Eck the Dutch governor of Ceylon, in his wars against King Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy, decided that he needed a competing candidate against Kirti Sri Rajasinha to the throne of Kandy. In 1762, Van Eck sent his delegate Marten Huysvoorn to Ayutthaya to ask the Siamese king Ekkathat to allow Thepphiphit or any of his sons to return to Ceylon as a competing claimant against Kirti Sri Rajasinha. The Dutch, however, did not know about political enmity between the half-brothers Ekkathat and Thepphiphit. The idea that Ekkathat's renegade half-brother and political enemy becoming a sovereign king of a foreign kingdom was unthinkable. Ekkathat did not allow any royal audiences with Huysvoorn. There were even rumors that the Dutch would soon attack Ayutthaya to put Thepphiphit on the Siamese throne, while Thepphiphit was still being grounded in Tenasserim. After many failed lobbies, Huysvoorn eventually left Ayutthaya empty-handed.

Van Eck did not give up. In 1764, Van Eck the Dutch governor of Ceylon sent Willem van Damast Limberger to directly search for Thepphiphit in Tenasserim, where Thepphiphit had been grounded but the Dutch mission failed to meet with Thepphiphit.

Eastern Siamese host

Thepphiphit remained in confinement in Tenasserim for nearly three years, with his family in Ayutthaya, until things took yet another turn in 1765. In early 1765, the Burmese invaded and conquer the Siamese Tenasserim Coast. Mergui fell to the Burmese in January 1765. Thepphiphit had to hurriedly flee the Burmese onslaught through the Singkhon Pass into the Gulf of Siam coast. Ekkathat again sent intendant to bring Thepphiphit to confinement in the new place of Chanthaburi on Eastern Siamese coastline, far from Ayutthaya.

Thepphiphit remained obedient to his half-brother King Ekkathat of Ayutthaya until mid-1766 when the Ayutthayan defenders realized that the Burmese besiegers would not leave for the wet rainy season. Situation of Ayutthaya worsened in its stand against the besieging Burmese and people began to leave Ayutthaya for safety if possible. In mid-1766, Thepphiphit made another important political move by leaving his confinement in Chanthaburi and went to Prachinburi, where he rallied Eastern Siamese forces to fight the Burmese. Eastern Siamese men from Eastern Siamese towns including Prachinburi, Nakhon Nayok, Chacheongsao, Chonburi and Bang Lamung rallied to Thepphiphit's host at Prachinburi.

Thepphiphit managed to gather 2,000 Eastern Siamese men and built himself a stockade at Paknam Yothaka on the Bangpakong River near Prachinburi. Thepphiphit's Eastern Siamese host was led by two local officials Muen Kao (Thai: หมื่นเก้า) and Muen Si Nawa (Thai: หมื่นศรีนาวา) from Prachinburi and a local leader Thongyu Noklek (Thai: ทองอยู่นกเล็ก) from Chonburi. Upon hearing about Thepphiphit's new host at Paknam Yothaka, Thepphiphit's family in Ayutthaya, including his wives, sons, daughter and servants, left Ayutthaya through the less-besieged eastern outskirts of Ayutthaya to join Thepphiphit at Prachinburi. A number of Ayutthayan people, having no hope in Ekkathat's regime, left Ayutthaya to join Thepphiphit. Phraya Rattanathibet the Minister of Palace Affairs and Ekkathat's many-time military commander, who had marched out against the Burmese in 1760 and 1765, also left Ayutthaya to join Thepphiphit. This showed that, in spite of political setbacks and many years of wandering, Thepphiphit still commanded a considerable loyalty in Ayutthaya and in Siam.

It is not known whether Thepphiphit's intention of rising in 1766 was patriotic or political, but Ekkathat would never trust his troublesome half-brother. Thepphiphit and his family stayed at Prachinburi while letting his subordinates Muen Kao, Muen Si Nawa and Thongyu Noklek to command his host at Paknam Yothaka. It was the Burmese who marched out from Ayutthaya to attack and defeat Thepphiphit's Eastern Siamese army at Paknam Yothaka. Muen Kao and Muen Si Nawa were killed in battle against the Burmese while Thongyu Noklek fled. Thepphiphit's force at Paknam Yothaka was eventually dispersed by the Burmese.

Thepphiphit, his family and Phraya Rattanathibet, upon learning about the fall of his stockade at Paknam Yothaka, left Prachinburi to take refuge at a place near Nakhon Nayok in the northeast. However, Phraya Rattanathibet fell ill and died there. Thepphiphit held a funeral for this minister who had shifted political allegiance from Ekkathat to Thepphiphit. After defeating Thepphiphit, the Burmese forces stationed at Prachinburi and along the Bangpakong River. It would be these Burmese regiments that Phraya Tak would face in his journey from Ayutthaya through Eastern Siam in January 1767.

Struggle in the Northeast

Prince Thepphiphit realized that staying near Nakhon Nayok made him vulnerable to Burmese attacks, so he decided to flee further through the Chong Ruea Taek Pass through the Dong Phaya Fai forests to the northeast to Nakhon Ratchasima or Khorat, which was the main Siamese city in the northeast. While Ayutthaya was being besieged by the Burmese, the Siamese Northeast was under the eponymous, locally powerful Chaophraya Nakhon Ratchasima the governor of the Nakhon Ratchasima. Thepphiphit was also accompanied by a large number of officials who had pledged loyalty to him. Thepphiphit was unsure about the political allegiance of Chaophraya Nakhon Ratchasima so he sent his officials to bring gifts to the governor. It turned out that Chaophraya Nakhon Ratchasima was an enemy of Thepphiphit when a minor official from the city came out to tell Thepphiphit that the governor had a plan to send 500 Cambodian men to arrest Thepphiphit for Ekkathat.

Realizing that he would find no allies there, Thepphiphit planned to flee further but his son Prince Momchao Prayong (Thai: หม่อมเจ้าประยงค์) urged his father Thepphiphit to stay and compete for power. Prince Prayong managed to gather a group of 550 local men and devised a plan to seize power in the Northeast. On the fourteenth waxing of the tenth month, Year 1128 of Culāsakaraj Era (17 September 1766), Prince Prayong led his forces to disguise themselves going into Nakhon Ratchasima. Next day, on September 18, Chaophraya Nakhon Ratchasima the eponymous governor was making Buddhist merits at a temple when he was ambushed and killed by the forces of Prince Prayong. Prince Prayong was able to seize Nakhon Ratchasima for his father Thepphiphit, who triumphantly entered the city. However, Luang Phaeng, brother of the murdered Chaophraya Nakhon Ratchasima, managed to flee to Phimai to the northeast of Nakhon Ratchasima.

Thepphiphit's triumph in the Northeast was short-lived, however. Luang Phaeng was vengeful and determined to avenge the death of his brother at the hands of Thepphiphit's son Prince Prayong. Luang Phaeng convinced Phra Phimai the governor of Phimai to retake Nakhon Ratchasima and to subjugate Thepphiphit. Only five days after Thepphiphit's victory that Thepphiphit found himself besieged in Nakhon Ratchasima by the forces from Phimai. Thepphiphit's defense lasted for four days when Nakhon Ratchasima fell to the Phimai forces in late September 1766. As Phra Phimai took control of Nakhon Ratchasima, Thepphiphit and his family suffered violent fates as Luang Phaeng exacted his vengeance. Thepphiphit's two eldest surviving sons, Prince Prayong and Prince Dara, were killed along with the most prominent of Thepphiphit's officials. Thepphiphit's daughter, Princess Ubon, was forced to become a wife of Kaen, a henceman of Luang Phaeng. Thepphiphit's wife, Lady Sem, was also forced to become a wife of Yon, another henceman of Luang Phaeng. Younger sons of Thepphiphit were spared.

Luang Phaeng contemplated the execution of Prince Thepphiphit himself but Phra Phimai insisted that Thepphiphit should be spared. Phra Phimai took Thepphiphit back to Phimai, where he kept Thepphiphit as a political pawn for his own power gain. When Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese in April 1767, Phra Phimai declared Thepphiphit a rightful ruler. Being technically in political hostage under Phra Phimai, Thepphiphit gave out noble titles as if he were a Siamese king. Thepphiphit appointed Phra Phimai as his chief minister with title Chaophraya Si Suriyawong (Thai: เจ้าพระยาศรีสุริยวงศ์). Two sons of Phra Phimai, Sa and Noi, were also appointed by Thepphiphit as Phraya Mahamontri and Phraya Worawongsa, respectively. This led to the conception of the Phimai regime, the Siamese regional regime of the Northeast, under nominal leadership of Thepphiphit.

Phra Phimai the chief minister of Thepphiphit decided to get rid of Luang Phaeng, his former ally who had been holding the city of Nakhon Ratchasima. In October 1767, Phra Phimai, along with his two sons Sa and Noi, visited Luang Phaeng at Nakhon Ratchasima with 500 men. Luang Phaeng was totally unsuspicious about his friend Phra Phimai as they enjoyed watching traditional performance together. Phra Phimai rose up to slash Luang Phaeng down to death with his sword. Sa and Noi, sons of Phra Phimai, also slashed Kaen and Yon, two hencemen of Luang Phaeng, to death with their swords. Bloodshed followed in Nakhon Ratchasima until Phra Phimai managed to seize power in the city on behalf of Thepphiphit. Phra Phimai also assigned his son Noi to govern Nakhon Ratchasima. By 1768, after the fall of Ayutthaya, Thepphiphit had entrenched himself in the Northeastern Siamese town of Phimai, leading his own regime with assistance from his chief minister Phra Phimai.

Subjugation by Taksin

Main article: Taksin's reunification of SiamIn January 1767, three months before the fall of Ayutthaya, Phraya Tak or Zheng Xin (鄭信) the Ayutthayan military commander with Teochew Chinese ancestry, led his own forces to break through the Burmese encirclement to the east to find a new position. Phraya Tak took journey from Ayutthaya to Nakhon Nayok and then proceeded down along the Bangpakong River to Eastern Siamese coastline. During his journey, Phraya Tak met and defeated a number of Burmese troops that had been occupying the area in the aftermath of the defeat of Thepphiphit's Eastern Siamese host. Phraya Tak eventually took position at Chanthaburi in June 1767.

Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese conquerors in April 1767. Ekkathat, Thepphiphit's half-brother and the last king of Ayutthaya, died during the fall. Uthumphon the temple king, another of Thepphiphit's half-brother, along with other members of the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty including Thepphiphit's half-sisters, was permanently deported to Burma. Thepphiphit, being stranded in the Northeast, did not suffer the same fate as his half-brothers but his family had been decimated by the political struggle in the Northeast.

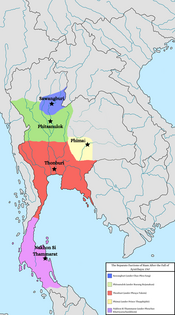

After the fall of Ayutthaya, Burmese conqueror forces were obliged to depart for the Sino–Burmese war front in June 1767, leaving a small garrison in Ayutthaya under the Mon official named Thugyi or Suki to impose the low-scale, short-lived Burmese occupation in Lower Central Siam. The rest of the kingdom coalesced into many competing regional regimes, including the Phimai regime of Thepphiphit in the Siamese Northeast, mainly encompassing the two main Siamese cities of Nakhon Ratchasima and Phimai. From Chanthaburi, Phraya Tak rallied his troops and sailed along Eastern Siamese shoreline to reconquer Ayutthaya. Phraya Tak managed to conquer the Burmese occupying forces under Thugyi at Phosamton (modern Bang Pahan district, to the north of Ayutthaya) in November 1767, ending the Burmese occupation. A Burmese official from Phosamton named Mongya escaped from the forces of Phraya Tak to the northeast to take shelter under Thepphiphit.

With Ayutthaya reduced to cinders, Phraya Tak established Thonburi as the new capital of Siam. Phraya Tak was enthroned as King Taksin of the new Siamese Kingdom of Thonburi in December 1767, ushering the new era of Thai history. The first main of objective of the new king Taksin was to unify the regional regimes. Surviving princes of the fallen Ban Phlu Luang dynasty were undeniably obstacles to the new Thonburi regime of Taksin. Thepphiphit was then the most prominent surviving prince but there were two other princes – Prince Chao Sisang, a son of Prince Thammathibet the deceased crown prince and half-brother of Thepphiphit, took refuge in Cambodia and Prince Chao Chui, a grandson of King Thaisa, took refuge at Hà Tiên under protection of the Cantonese lord Mạc Thiên Tứ. Among the regional regimes, only Thepphiphit potentially clamed legitimacy to Ayutthaya as he was a surviving prince of the fallen dynasty.

In efforts to acquire imperial investiture from the Qing Chinese imperial court in order to resume the lucrative Sino-Siamese tributary trade to boost Thonburi's royal revenue, King Taksin sent a Chinese merchant as his delegate to Guangzhou in September 1768. However, Emperor Qianlong gave a very negative response, rebuking that Taksin should restore the Siamese throne to a surviving prince of the fallen dynasty instead of making himself king. Thepphiphit appeared for the first time in Chinese documents as Zhao Wangji (詔王吉) during this occasion, mentioned as one of the rightful heirs to Siam; "Zhao Wangji (Thepphiphit), who is the elder brother of your ruler (Ekkathat) and Zhao Cui (Prince Chao Chui) as well as Zhao Shichang (Prince Chao Sisang) who are grandsons of the ruler, are all hiding within the territory."

In late 1768, King Taksin targeted the Phimai regime of Thepphiphit and called out Thepphiphit for harboring the Burmese enemy Mongya. This move might be motivated by Taksin's efforts to put down any remaining princes of the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty in order to get rid of any competitors for investiture from the Chinese imperial court. Taksin, along with his commanders Phra Ratchawarin (future king Rama I) and Phra Mahamontri (future Prince Sura Singhanat) marched his Thonburi army to cross the Dong Phaya Fai forests to attack Nakhon Ratchasima. Thepphiphit sent his chief minister Phra Phimai or Chaophraya Si Suriyawong, along with Phimai's son Phraya Mahamontri Sa and the Burmese man Mongya himself, to take position at Dan Khunthot to the east of Nakhon Ratchasima. Phraya Worawongsa Noi, another son of Phimai, also took position at Choho near the city.

Thonburi forces under Phra Ratchawarin prevailed over Thepphiphit's forces at Dan Khunthot. Phra Phimai the chief minister of Thepphiphit, his son Sa and the Burmese man Mongya were all captured and executed. King Taksin himself seized control of Choho and took possession of the Nakhon Ratchasima city. Phraya Noi, another son of Phra Phimai, managed to escape from Choho across the Dangrek mountains into Cambodia. Taksin sent his forces to pursue Phraya Noi as far as Siemreap in Cambodia but Phraya Noi was never found.

Upon learning of the defeat and deaths of his commanders, Thepphiphit and his surviving family members hurriedly packed up and fled to the northeast towards Laos. However, a local official named Khun Chana (Thai: ขุนชนะ) captured Thepphiphit, along with his wife, daughter and sons. Khun Chana brought Thepphiphit and his family to King Taksin at Nakhon Ratchasima. Taksin rewarded Khun Chana, for successful capture of Thepphiphit, with position of the governor of Nakhon Ratchasima the Lord of the Northeast.

Execution and Legacy

Thepphiphit, along with his family, were captured in November 1768. Thepphiphit and his family were brought to Thonburi. According to the dramatic account of Thai historical chronicles, Thepphiphit refused to kowtow before Taksin, taking the pride of an Ayutthayan prince. King Taksin reportedly said to Thepphiphit: "You lack merit and power. Anywhere you went, your supporters all died. If I spare you, there will be more of your admirers who would die for you. You should not live. You should die this time, so that there will be no more insurrections in the kingdom." (Thai: ตัวจ้าวหาบุญวาศนาบาระมีมิได้ ไปอยู่ที่ใดก็ภาพวกพ้องผู้คนที่นับถือพลอยพินาศฉิบหายที่นั่น ครั้นจะเลี้ยงจ้าวไว้ก็จภาคนที่หลงเชื่อถือบุญพลอยล้มตายเสียด้วยกัน จ้าวอย่าอยู่เลยจงตายเสียครั้งนี้ทีเดียวเถีด อย่าให้จุลาจลในแผ่นดินสืบไปข้างน่าอีกเลย) Thepphiphit was eventually executed 4 December 1768, ending the life of the prince, who was the scion of the fallen Ayutthayan dynasty, who had ventured and explored many political scenarios and journeys, at around the age of fifty years old.

Thepphiphit's daughter, Princess Ubon, became one of the consorts of King Taksin. Thepphiphit's wife Lady Sem also entered the Thonburi Palace as a maidservant. Thepphiphit's two surviving young sons, Prince Mongkhon and Prince Lamduan, were spared and allowed to live in the Thonburi court. Princess Ubon, daughter of Thepphiphit, also met a violent end. King Taksin took other Ayutthayan princess, Princess Chim, a great-granddaughter of King Phetracha, as his consort. An incident happened in 1769 when Taksin sent two Portuguese men to capture some rats in the women's palace. The two Portuguese men were found having romantic relations with Princess Chim and Princess Ubon, caught in the act. The two Portuguese men escaped with their lives as the two princesses were put to interrogation. Adultery of royal consorts would be harshly punished, according to the Siamese law. Princess Ubon, daughter of Thepphiphit, denied the allegations but Princess Chim convinced Princess Ubon to accept the fate, saying "Why do you insist to live as a riding queen? We should follow our fathers to death." (Thai: ยังจะอยู่เปนมเหษีคี่ซ้อนฤๅมาตายตามเจ้าพ่อเถิด). As they were found guilty, Taksin ordered his oarsmen to sexually assault the two princesses in public to shame them. Princess Chim and Princess Ubon were executed on the first waning of the seventh month, Year 1131 of the Culāsakaraj Era (20 June 1769) by decapitations. Their limbs were amputated and their chests were sliced open.

When Princess Ubon, daughter of Thepphiphit and a consort of King Taksin, was executed in June 1769, she was already two-month pregnant with Taksin. Taksin was so filled with guilt and remorse that he planned a suicide. Taksin asked if any of his subjects were loyal enough to follow him to death. Lady Sem, wife of the deceased Thepphiphit, was one of the palace ladies who volunteered to follow the king to death. Fortunately, a high-ranking palace lady invited some venerable Buddhist monks to successfully talk the king to abandon his suicide plan.

Qing imperial court of Emperor Qianlong sent Zheng Rui (鄭瑞) to Hà Tiên in December 1768 to investigate about the fall of Ayutthaya. Zheng Rui brought reports and testimonies from Hà Tiên back to Guangzhou in July 1769, narrating the political situation in Siam and calling the deceased Thepphiphit as Zhao Wangji. These reports provided a detailed description of the life of Thepphiphit. The report also mentioned that Thepphiphit was executed on the 25th day of the tenth Chinese lunar month (4 December 1768).

References

- ^ Ruangsilp, Bhawan (2007). Dutch East India Company Merchants at the Court of Ayutthaya: Dutch Perceptions of the Thai Kingdom, C.1604-1765. Brill.

- ^ Wang, Gungwu (2004). Maritime China in Transition 1750-1850. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Erika, Masuda (2007). "The Fall of Ayutthaya and Siam's Disrupted Order of Tribute to China (1767-1782)". Taiwan Journal of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "WAT PRADU SONGTHAM". History of Ayutthaya.

- ^ Codrington, H.W. (1995). Short History of Ceylon. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120609464.

- ^ Lehrer, Tyler A. (2022). "Traveling Monks and the Troublesome Prince: On the Aftermath of the Dutch VOC's Mediation of Buddhist Connection between Kandy and Ayutthaya". Journal of Social Sciences (New Series), Research Centre for Social Sciences, University of Kelaniya. 1 – via Academia.

- ^ Nierstrasz, Chris (2012). In the Shadow of the Company: The Dutch East India Company and Its Servants in the Period of Its Decline (1740-1796). Brill. ISBN 9789004235830.

- ^ Blussé, Leonard; Dening, Nie (2018). The Chinese Annals of Batavia, the Kai Ba Lidai Shiji and Other Stories (1610-1795). Brill. ISBN 9789004356702.

- Emmer, Pieter C.; Gommans, Jos J.L. (2020). The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108428378.

- ^ พระราชพงศาวดารฉบับสมเด็จพระพนรัตน์วัดพระเชตุพน ตรวจสอบชำระจากเอกสารตัวเขียน (in Thai). 2015.

- ^ Rappa, Antonio L. (21 April 2017). The King and the Making of Modern Thailand. Routledge.

- Arthayukti, Woraphat; Van Roy, Edward (2012). "Heritage Across Borders: The Funerary Monument of King Uthumphon" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand: A Short History. Silkworm Books.

- Mishra, Patit Paban (2010). The History of Thailand. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (2018). China and Southeast Asia: Historical Interactions. Routledge.

- ^ Breazeale, Kennon (1999). From Japan to Arabia; Ayutthaya's Maritime Relations with Asia. Bangkok: Foundation for the promotion of Social Sciences and Humanities Textbook Project.

- "KING TAKSIN DAY". Ministry of Culture. 22 Aug 2015.

- ^ พระราชวิจารณ์ จดหมายความทรงจำ ของ พระเจ้าไปยิกาเธอ กรมหลวงนรินทรเทวี (เจ้าครอกวัดโพ) ตั้งแต่ จ.ศ. ๑๑๒๙ ถึง ๑๑๘๒ เปนเวลา ๕๓ ปี (in Thai). 1908.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1592 – 1815 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||