Instant messaging (IM) technology is a type of synchronous computer-mediated communication involving the immediate (real-time) transmission of messages between two or more parties over the Internet or another computer network. Originally involving simple text message exchanges, modern IM applications and services (also called "social messengers", "messaging apps", "chat apps" or "chat clients") tend to also feature the exchange of multimedia, emojis, file transfer, VoIP (voice calling), and video chat capabilities.

Instant messaging systems facilitate connections between specified known users (often using a contact list also known as a "buddy list" or "friend list") or in chat rooms, and can be standalone apps or integrated into a wider social media platform, or in a website where it can, for instance, be used for conversational commerce. Originally the term "instant messaging" was distinguished from "text messaging" by being run on a computer network instead of a cellular/mobile network, being able to write longer messages, real-time communication, presence ("status"), and being free (only cost of access instead of per SMS message sent).

Instant messaging was pioneered in the early Internet era; the IRC protocol was the earliest to achieve wide adoption. Later in the 1990s, ICQ was among the first closed and commercialized instant messengers, and several rival services appeared afterwards as it became a popular use of the Internet. Beginning with its first introduction in 2005, BlackBerry Messenger became the first popular example of mobile-based IM, combining features of traditional IM and mobile SMS. Instant messaging remains very popular today; IM apps are the most widely used smartphone apps: in 2018 for instance there were 980 million monthly active users of WeChat and 1.3 billion monthly users of WhatsApp, the largest IM network.

Overview

See also: Synchronous computer-mediated communicationInstant messaging (IM), sometimes also called "messaging" or "texting", consists of computer-based human communication between two users (private messaging) or more (chat room or "group") in real-time, allowing immediate receipt of acknowledgment or reply. This is in direct contrast to email, where conversations are not in real-time, and the perceived quasi-synchrony of the communications by the users (although many systems allow users to send offline messages that the other user receives when logging in).

Earlier IM networks were limited to text-based communication, not dissimilar to mobile text messaging. As technology has moved forward, IM has expanded to include voice calling using a microphone, videotelephony using webcams, file transfer, location sharing, image and video transfer, voice notes, and other features.

IM is conducted over the Internet or other types of networks (see also LAN messenger). Depending on the IM protocol, the technical architecture can be peer-to-peer (direct point-to-point transmission) or client–server (when all clients have to first connect to the central server). Primary IM services are controlled by their corresponding companies and usually follow the client-server model.

The term "Instant Messenger" is a service mark of Time Warner and may not be used in software not affiliated with AOL in the United States. For this reason, in April 2007, the instant messaging client formerly named Gaim (or gaim) announced that they would be renamed "Pidgin".

Clients

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Modern IM services generally provide their own client, either a separately installed software or a browser-based client. They are normally centralised networks run by the servers of the platform's operators, unlike peer-to-peer protocols like XMPP. These usually only work within the same IM network, although some allow limited function with other services (see #Interoperability). Third-party client software applications exist that will connect with most of the major IM services. There is the class of instant messengers that uses the serverless model, which doesn't require servers, and the IM network consists only of clients. There are several serverless messengers: RetroShare, Tox, Bitmessage, Ricochet, Ring. See also: LAN messenger.

Some examples of popular IM services today include Signal, Telegram, WhatsApp Messenger, WeChat, QQ Messenger, Viber, Line, and Snapchat. The popularity of certain apps greatly differ between different countries. Certain apps have an emphasis on certain uses - for example, Skype focuses on video calling, Slack focuses on messaging and file sharing for work teams, and Snapchat focuses on image messages. Some social networking services offer messaging services as a component of their overall platform, such as Facebook's Facebook Messenger, who also own WhatsApp. Others have a direct IM function as an additional adjunct component of their social networking platforms, like Instagram, Reddit, Tumblr, TikTok, Clubhouse and Twitter; this also includes for example dating websites, such as OkCupid or Plenty of Fish, and online gaming chat platforms.

Features

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Private and group messaging

Private chat allows users to converse privately with another person or a group. Privacy can also be enhanced in several ways, such as end-to-end encryption by default. Public and group chat features allow users to communicate with multiple people simultaneously.

Calling

Many major IM services and applications offer a call feature for user-to-user voice calls, conference calls, and voice messages. The call functionality is useful for professionals who utilize the application for work purposes and as a hands-free method. Videotelephony using a webcam is also possible by some.

Games and entertainment

Some IM applications include in-app games for entertainment. Yahoo! Messenger, for example, introduced these where users could play a game and viewed by friends in real-time. MSN Messenger featured a number of playable games within the interface. Facebook's Messenger has had a built-in option to play games with people in a chat, including games like Tetris and Blackjack. Discord features multiple games built inside the "activities" tab in voice channels.

Payments

A relatively new feature to instant messaging, peer-to-peer payments are available for financial tasks on top of communication. The lack of a service fee also makes these advantageous to financial applications. IM services such as Facebook Messenger and the WeChat 'super-app' for example offer a payment feature.

History

| 1988 | Internet Relay Chat |

|---|---|

| 1989–1995 | |

| 1996 | ICQ |

| 1997 | AIM |

| 1998 | Yahoo! Messenger |

| 1999 | XMPP MSN Messenger |

| 2000–2002 | |

| 2003 | Xfire |

| 2004–2008 | |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | Kik Messenger |

| 2011 | Facebook Messenger Snapchat |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | Telegram |

| 2014 | Signal |

| 2015 | Discord |

Early systems

Though the term dates from the 1990s, instant messaging predates the Internet, first appearing on multi-user operating systems like Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) and Multiplexed Information and Computing Service (Multics) in the mid-1960s. Initially, some of these systems were used as notification systems for services like printing, but quickly were used to facilitate communication with other users logged into the same machine. CTSS facilitated communication via text message for up to 30 people.

Parallel to instant messaging were early online chat facilities, the earliest of which was Talkomatic (1973) on the PLATO system, which allowed 5 people to chat simultaneously on a 512 x 512 plasma display (5 lines of text + 1 status line per person). During the bulletin board system (BBS) phenomenon that peaked during the 1980s, some systems incorporated chat features which were similar to instant messaging; Freelancin' Roundtable was one prime example. The first such general-availability commercial online chat service (as opposed to PLATO, which was educational) was the CompuServe CB Simulator in 1980, created by CompuServe executive Alexander "Sandy" Trevor in Columbus, Ohio.

As networks developed, the protocols spread with the networks. Some of these used a peer-to-peer protocol (e.g. talk, ntalk and ytalk), while others required peers to connect to a server (see talker and IRC). The Zephyr Notification Service (still in use at some institutions) was invented at MIT's Project Athena in the 1980s to allow service providers to locate and send messages to users.

Early instant messaging programs were primarily real-time text, where characters appeared as they were typed. This includes the Unix "talk" command line program, which was popular in the 1980s and early 1990s. Some BBS chat programs (i.e. Celerity BBS) also used a similar interface. Modern implementations of real-time text also exist in instant messengers, such as AOL's Real-Time IM as an optional feature.

In the latter half of the 1980s and into the early 1990s, the Quantum Link online service for Commodore 64 computers offered user-to-user messages between concurrently connected customers, which they called "On-Line Messages" (or OLM for short), and later "FlashMail." Quantum Link later became America Online and made AOL Instant Messenger (AIM, discussed later). While the Quantum Link client software ran on a Commodore 64, using only the Commodore's PETSCII text-graphics, the screen was visually divided into sections and OLMs would appear as a yellow bar saying "Message From:" and the name of the sender along with the message across the top of whatever the user was already doing, and presented a list of options for responding. As such, it could be considered a type of graphical user interface (GUI), albeit much more primitive than the later Unix, Windows and Macintosh based GUI IM software. OLMs were what Q-Link called "Plus Services" meaning they charged an extra per-minute fee on top of the monthly Q-Link access costs.

Development of the Internet Relay Chat (IRC) protocol began in 1989, and this would become the Internet's first widespread instant messaging standard.

Graphical messengers

Modern, Internet-wide, GUI-based messaging clients as they are known today, began to take off in the mid-1990s with PowWow, ICQ, and AOL Instant Messenger (AIM). Similar functionality was offered by CU-SeeMe in 1992; though primarily an audio/video chat link, users could also send textual messages to each other. AOL later acquired Mirabilis, the authors of ICQ; establishing dominance in the instant messaging market. A few years later ICQ (then owned by AOL) was awarded two patents for instant messaging by the U.S. patent office. Meanwhile, other companies developed their own software; (Excite, Microsoft (MSN), Ubique, and Yahoo!), each with its own proprietary protocol and client; users therefore had to run multiple client applications if they wished to use more than one of these networks. However, the open protocol IRC continued to be popular by the millennium, and its most popular graphical app was mIRC.

While instant messaging was mainly in use for consumer recreational purposes, in 1998, IBM launched their Lotus Sametime instant messenger software, the first popular example of enterprise-grade instant messaging. In 2000, an open-source application and open standards-based protocol called Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP) was launched, initially branded as Jabber. XMPP servers could act as gateways to other IM protocols, reducing the need to run multiple clients.

Video calling using a webcam also started taking off during this time. Microsoft's NetMeeting, which was focused on business "web conferencing", was one of the earliest; the company then launched Windows Messenger, coming preloaded on Windows XP, featuring video capabilities. Yahoo! Messenger added video capabilities in 2001; by 2005, such features were built-in also in AIM, MSN Messenger, and Skype.

There were a reported 100 million users of instant messaging in 2001. As of 2003, AIM was the globally most popular instant messenger with 195 million users and exchanges of 1.6 billion messages daily. By 2006, AIM controlled 52 percent of the instant messaging market, but rapidly declined shortly thereafter as the company struggled to compete with other services.

Integrated IM and mobile

Instant messaging integrated in other services started picking up pace in the late 2000s. Myspace, the then-largest social networking service, launched Myspace IM in 2006, shortly after Google's Gtalk, which was integrated into its Gmail webmail interface. Facebook Chat launched in 2008, providing IM to users of the social network. By 2010, traditional instant messaging was in sharp decline in favor of these new messaging features on wider social networks, which at the time were not normally called IM. For instance, AIM's userbase had declined by more than half throughout the year 2011.

Standalone instant messenger services were revived, evolving into becoming primarily being used on mobile due to the increasing use of Internet-enabled cell phones and smartphones. Often called "chat apps", to distinguish it from cellular-based SMS and MMS "texting" services, these newer services were specially designed to be run on mobile platforms, as opposed to older services like AIM and MSN; BlackBerry Messenger, released in 2005, was one of the influential pioneers of mobile IM, and led to other companies launching services with proprietary protocols, such as WhatsApp. Mobile instant messaging surpassed SMS in global message volume by 2013. While SMS relied on traditional paid telephone services, IM apps on mobile were available for free or a minor data charge.

Older IM services were eventually shut, including AIM and Yahoo! Messenger, and also Windows Live Messenger, which merged into Skype in 2013. In 2014, it was reported that instant messaging had more users than social networks. Concurrently, rising use of instant messaging at workplaces led to the creation of new services (enterprise application integration (EAI)) often integrated with other enterprise applications such as workflow systems, for example in Skype for Business, Slack and Microsoft Teams. Meanwhile, the launch of Discord in 2015 has marked a notable new example of traditional IM originally designed for desktops.

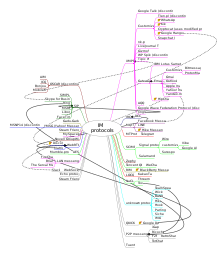

Interoperability

Most IM protocols are proprietary and are not designed to be interoperable with others, meaning that many IM networks have been incompatible and users have been unable to reach users on other networks. As of 2024, fragmentation of IM services means that a typical user is likely to have to use more networks than ever, including the need to download the apps and signing up, to stay in touch with all their contacts. However, there had been attempts for solutions.

Multi-protocol clients can use any of the IM protocols by using additional local libraries for each protocol. Examples of multi-protocol instant messenger software include Pidgin and Trillian, and more recently Beeper. These third-party clients have often been unable to keep up due to proprietary protocol restrictions and getting locked out of it. For instance, in 2015, WhatsApp started banning users who were using unofficial clients. Major IM providers usually cite the need for formal agreements, and security concerns as reasons for making changes.

Attempted open standards

There have been several attempts in the past to create a unified standard for instant messaging, including:

- IETF's Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) and SIP for Instant Messaging and Presence Leveraging Extensions (SIMPLE)

- Application Exchange (APEX),

- Instant Messaging and Presence Protocol (IMPP),

- Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), based on XML, and

- Open Mobile Alliance's Instant Messaging and Presence Service (IMPS), developed specifically for mobile devices.

History and agreements

Evan Hansen, CNET, January 2001Critics say AOL's slowness in embracing interoperability has caused setbacks to other companies trying to grow their businesses. AOL has said it supports the development of an interoperable system for all IM networks but has cited privacy and security concerns as the reasons it's taking its time. Competitors have labeled that argument a "smoke screen."

In the early 2000s, when instant messaging was quickly growing, most attempts at producing a unified standard for the-then major IM providers (AOL, Yahoo!, Microsoft) had failed. There was a "bitter row" between AOL and its rivals regarding the opening up of their networks. In 2000, U.S. regulatory Federal Communications Commission (FCC) proposed, and supported by Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, that AOL providing interoperability of its AIM and ICQ instant messengers with Microsoft's MSN Messenger was a condition for the forthcoming AOL-Time Warner merger.

However, in 2004, Microsoft, Yahoo! and AOL agreed to a deal in which Microsoft's enterprise IM server Live Communications Server 2005 would have the possibility to talk to their rival counterparts and vice versa. On October 13, 2005, Microsoft and Yahoo! announced that their IM networks would soon be interoperable, using SIP/SIMPLE. This was finally rolled out to Windows Live Messenger and Yahoo! Messenger users in July 2006. Additionally, in December 2005 by the AOL and Google strategic partnership deal, it was announced that AIM and ICQ users would be able to communicate with Google Talk users. However this feature took until December 2007 to roll out. XMPP provided the best example of open protocol interoperability, having had gateways that connected to Google Talk, Lotus Sametime and others.

Later, RCS was developed by telecommunication companies as an instant messaging protocol to replace SMS under a unified standard. In 2022, the European Union passed the Digital Markets Act, which largely came into effect in early 2023. Among other things, the legislation mandates certain interoperability between the largest IM platforms in use in Europe. As a result, in March 2024, Meta Platforms opened up its WhatsApp and Messenger networks to be interoperable.

Technical

There are two ways to combine the many disparate protocols:

- Combine the many disparate protocols inside the IM client application.

- Combine the many disparate protocols inside the IM server application. This approach moves the task of communicating with the other services to the server. Clients need not know or care about other IM protocols. For example, LCS 2005 Public IM Connectivity. This approach is popular in XMPP servers; however, the so-called transport projects suffer the same reverse engineering difficulties as any other project involved with closed protocols or formats.

Some approaches allow organizations to deploy their own, private instant messaging network by enabling them to restrict access to the server (often with the IM network entirely behind their firewall) and administer user permissions. Other corporate messaging systems allow registered users to also connect from outside the corporation LAN, by using an encrypted, firewall-friendly, HTTPS-based protocol. Usually, a dedicated corporate IM server has several advantages, such as pre-populated contact lists, integrated authentication, and better security and privacy.

Effects of IM on communication

See also: Text messaging § Social effectsWorkplace communication

Instant messaging has changed how people communicate in the workplace. Enterprise messaging applications like Slack, TeleMessage, Teamnote and Yammer allow companies to enforce policies on how employees message at work and ensure secure storage of sensitive data. They allow employees to separate work information from their personal emails and texts.

Messaging applications may make workplace communication efficient, but they can also have consequences on productivity. A study at Slack showed on average, people spend 10 hours a day on Slack, which is about 67% more time than they spend using email.

Instant messaging is implemented in many video-conferencing tools. A study of chat use during work-related videoconferencing found that chat during meetings allows participants to communicate without interrupting the meeting, plan action around common resources, and enables greater inclusion. The study also found that chat can cause distractions and information asymmetries between participants.

Language

See also: SMS language, Emoji, and Emoticon

Users sometimes make use of internet slang or text speak to abbreviate common words or expressions to quicken conversations or reduce keystrokes. The language has become widespread, with well-known expressions such as 'lol' translated over to face-to-face language.

Emotions are often expressed in shorthand, such as the abbreviation LOL, BRB and TTYL; respectively laugh(ing) out loud, be right back, and talk to you later. Some, however, attempt to be more accurate with emotional expression over IM. Real time reactions such as (chortle) (snort) (guffaw) or (eye-roll) have been popular at one point. Also there are certain standards that are being introduced into mainstream conversations including, '#' indicates the use of sarcasm in a statement and '*' which indicates a spelling mistake and/or grammatical error in the prior message, followed by a correction.

Business application

Instant messaging products can usually be categorised into two types: Enterprise Instant Messaging (EIM) and Consumer Instant Messaging (CIM). Enterprise solutions use an internal IM server, however this is not always feasible, particularly for smaller businesses with limited budgets. The second option, using a CIM provides the advantage of being inexpensive to implement and has little need for investing in new hardware or server software. IM is increasingly becoming a feature of enterprise software rather than a stand-alone application.

Instant messaging has proven to be similar to personal computers, email, and the World Wide Web, in that its adoption for use as a business communications medium was driven primarily by individual employees using consumer software at work, rather than by formal mandate or provisioning by corporate information technology departments. Tens of millions of the consumer IM accounts in use are being used for business purposes by employees of companies and other organizations. The adoption of IM across corporate networks outside of the control of IT organizations creates risks and liabilities for companies who do not effectively manage and support IM use. IM was initially shunned by the corporate world partly due to security concerns, but by 2003 many had started embracing these new services.

Software

In response to the demand for business-grade IM and the need to ensure security and legal compliance, a new type of instant messaging, called "Enterprise Instant Messaging" ("EIM") was created when Lotus Software launched IBM Lotus Sametime in 1998. Microsoft followed suit shortly thereafter with Microsoft Exchange Instant Messaging, later created a new platform called Microsoft Office Live Communications Server, and released Office Communications Server 2007 in October 2007. Oracle Corporation also jumped into the market with its Oracle Beehive unified collaboration software.

Both IBM Lotus and Microsoft have introduced federation between their EIM systems and some of the public IM networks so that employees may use one interface to both their internal EIM system and their contacts on AOL, MSN, and Yahoo. As of 2010, leading EIM platforms include IBM Lotus Sametime, Microsoft Office Communications Server, Jabber XCP and Cisco Unified Presence. Industry-focused EIM platforms such as Reuters Messaging and Bloomberg Messaging also provide IM abilities to financial services companies.

Security and archiving

Crackers (malicious or black hat hackers) have consistently used IM networks as vectors for delivering phishing attempts, drive-by URLs, and virus-laden file attachments, with over 1100 discrete attacks listed by the IM Security Center in 2004–2007. Hackers use two methods of delivering malicious code through IM: delivery of viruses, trojan horses, or spyware within an infected file, and the use of "socially engineered" text with a web address that entices the recipient to click on a URL connecting him or her to a website that then downloads malicious code.

IM connections sometimes occur in plain text, making them vulnerable to eavesdropping. Also, IM client software often requires the user to expose open UDP ports to the world, raising the threat posed by potential security vulnerabilities.

In the early 2000s, a new class of IT security providers emerged to provide remedies for the risks and liabilities faced by corporations who chose to use IM for business communications. The IM security providers created new products to be installed in corporate networks for the purpose of archiving, content-scanning, and security-scanning IM traffic moving in and out of the corporation. Similar to the e-mail filtering vendors, the IM security providers focus on the risks and liabilities described above.

With the rapid adoption of IM in the workplace, demand for IM security products began to grow in the mid-2000s. By 2007, the preferred platform for the purchase of security software had become the "computer appliance", according to IDC, who estimated that by 2008, 80% of network security products would be delivered via an appliance.

By 2014, however, instant messengers' safety level was still extremely poor. According to a scorecard by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, only 7 out of 39 instant messengers received a perfect score. In contrast, the most popular instant messengers at the time only attained a score of 2 out of 7. A number of studies have shown that IM services are quite vulnerable for providing user privacy.

In 2023, cybersecurity researchers discovered that numerous malicious "mods" exist of the Telegram instant messenger, which is freely available for download from Google Play.

Message history

Instant messages are often logged in a local message history, similar to emails' persistent nature. IM networks may store messages with either local-based device storage (e.g. WhatsApp, Viber, Line, WeChat, Signal etc. software) or cloud-based server storage provided by the service (e.g. Telegram, Skype, Facebook Messenger, Google Meet/Chat, Discord, Slack etc.). Although cloud-based storage is advertised to offer encrypted messages, it poses an increased risk that the IM provider may have access to the decryption keys and view the user's saved messages.

This requires users to trust IM servers and providers because messages can generally be accessed by the company. Companies may be compelled to reveal their user's communication and suspend user accounts for any reason.

Tracking and spying

News reports from 2013 revealed that the NSA is not only collecting emails and IM messages but also tracking relationships between senders and receivers of those chats and emails in a process known as metadata collection. Metadata refers to the data concerned about the chat or email as opposed to contents of messages. It may be used to collect valuable information.

In January 2014, Matthew Campbell and Michael Hurley filed a class-action lawsuit against Facebook for breaching the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. They alleged that the information in their supposedly private messages was being read and used to generate profit, specifically "for purposes including but not limited to data mining and user profiling".

In corporate use of IM, organizational offerings have become very sophisticated in their security and logging measures. An employee or organization member must be granted login credentials and permission to use the messaging system. Creating a specific account for each user allows the organization to identify, track and record all use of their messenger system on their servers.

Encryption

Encryption is the primary method that instant messaging apps use to protect user's data privacy and security. For corporate use, encryption and conversation archiving are usually regarded as important features due to security concerns. There are also a bunch of open source encrypting messengers.

IM does hold potential advantages over SMS. SMS messages are not encrypted, making them insecure, as the content of each SMS message is visible to mobile carriers and governments and can be intercepted by a third party, may leak metadata (such as phone numbers), or be spoofed and the sender of the message can be edited to impersonate another person.

Current instant messaging networks that use end-to-end encryption include Signal, WhatsApp, Wire and iMessage. Applications that have been criticized for lacking or poor encryption methods include Telegram and Confide, as both are prone to error or not having encryption enabled by default.

Compliance risks

In addition to the malicious code threat, using instant messaging at work creates a risk of non-compliance with laws and regulations governing electronic communications in businesses. In the United States alone, there are over 10,000 laws and regulations related to electronic messaging and records retention. The better-known of these include the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, HIPAA, and SEC 17a-3.

Clarification from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) was issued to member firms in the financial services industry in December 2007, noting that "electronic communications", "email", and "electronic correspondence" may be used interchangeably and can include such forms of electronic messaging as instant messaging and text messaging. Changes to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, effective December 1, 2006, created a new category for electronic records which may be requested during discovery in legal proceedings.

Most nations also regulate electronic messaging and records retention similarly to the United States. The most common regulations related to IM at work involve producing archived business communications to satisfy government or judicial requests under law. Many instant messaging communications fall into the category of business communications that must be archived and retrievable.

Current user base

As of March 2022, the most used instant messaging apps and services worldwide include: Signal with 100 million, Line with 217 million, Viber with 260 million, Telegram with 700 million, WeChat with 1.2 billion, Facebook Messenger with 1.3 billion, and WhatsApp with 2.0 billion users. There are 25 countries in the world where WhatsApp messenger is not the market leader in IM, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Philippines, and China.

IM apps have varying levels of adoption in different countries. As of April 2022:

- WhatsApp by Meta Platforms is the most popular instant messaging network in several countries in South America, Western Europe, Africa, Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

- Facebook Messenger by Meta Platforms is the most popular instant messaging network in North America, Northern Europe, some Central Europe countries, and Oceania.

- Telegram is the most popular instant messaging app in several Eastern Europe countries, and the second preferred option after WhatsApp in several countries in Western Europe, Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, Central and South America.

- Viber by Rakuten has a strong presence in Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, Ukraine, Russia). It is also moderately successful in Philippines and Vietnam.

- Line by Naver Corporation is used widely in some countries in Asia (Japan, Taiwan, Thailand).

- Instant messaging apps and services that are predominately used in only one country include: KakaoTalk in South Korea, Zalo in Vietnam, WeChat in China, and imo in Qatar.

- While not the dominant app for one-to-one messaging in any country, Discord is commonly used among online communities due to its ability to support chats with a large amount of members, topic-based channels, and cloud-based storage.

See also

Terms

- Ambient awareness – Term used to describe a form of peripheral social awareness

- Communication protocol – System for exchanging messages between computing systems

- Mass collaboration – Many people working on a single project

- Message-oriented middleware – Type of software or hardware infrastructure

- Operator messaging – Messaging answer service

- Social media – Virtual online communities

- Text messaging – Act of typing and sending a brief, digital message

- SMS – Text messaging service component

- Unified communications – Business and marketing concept / Messaging

Lists

- Comparison of cross-platform instant messaging clients

- Comparison of instant messaging protocols

- Comparison of user features of messaging platforms

Other

- Code Shikara – Family of malware worms that spreads through instant messagingPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

References

- "What is Instant Messaging? - Definition from SearchUnifiedCommunications". Unified Communications. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Will instant messaging be the new texting?". 2003-06-30. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- "MMS-multi media messaging and MMS-interconnection". Electronic Communications Committee (ECC). 2004.

- Foderaro, Lisa W. (2005-01-09). "Young Cell Users Rack Up Debt, a Message at a Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- "History of IRC". 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- "The Evolution of Instant Messaging". 17 November 2016.

- ^ "How BlackBerry Messenger Forever Changed the Way We Text". Inverse. 2023-05-09. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- ^ "RIP, ICQ: Why all instant messaging disappears (in the end)". ZDNET. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "8 Examples of Instant Messaging | ezTalks". www.eztalks.com. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- Clifford, Catherine (2013-12-11). "Top 10 Apps for Instant Messaging (Infographic)". Entrepreneur. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- "Part 1. Introduction: The basics of instant messaging". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2004-09-01. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- "How Instant Messaging Works". HowStuffWorks. 2001-03-28. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- "Summary of Final Decisions Issued by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- "Important and Long Delayed News". April 6, 2007. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007.

- "Yahoo! Messenger Launches "Imvironments™" with Next Generation of Yahoo! Messenger Service | Altaba Inc".

- "How to play ALL of Facebook Messenger's new games". Digital Spy. 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Discord Activities: Play Games and Watch Together". discord.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- vincithevin (2024-08-02). "Beijing Visitor's Guide: A Guide to Payment Services in the Capital". www.thebeijinger.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Fetter, Mirko (2019). New Concepts for Presence and Availability in Ubiquitous and Mobile Computing. University of Bamberg Press. p. 38. ISBN 9783863096236.

The basic concept of sending instantaneously messages to logged in users came with ... CTSS ...

- Tom Van Vleck. "Instant Messaging on CTSS and Multics". Multicians.org. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ "A Brief History of Chat Apps · Guide to Chat Apps". towcenter.gitbooks.io. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- CompuServe Innovator Resigns After 25 Years, The Columbus Dispatch, May 11, 1996, p. 2F

- Wired and Inspired, The Columbus Dispatch (Business page), by Mike Pramik, November 12, 2000

- "AOL Instant Messenger's Real-Time IM feature". Help.aol.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- "RealJabber.org's animation of real-time text". Realjabber.org. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- "Screenshot of a Quantum Link OLM". Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Andrei, Mihai (2018-11-09). "The Internet Relay Chat (IRC) turned 30 -- and it probably changed our lives". ZME Science. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Tay, Liz (2008-07-08). "IBM touts unification of consumer and business communication tools". iTnews. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "XMPP". xmpp.org. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "New Yahoo IM chats up broadband". CNET. 2002-08-15. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Yahoo! Messenger offers video option - Jun. 26, 2001". money.cnn.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Skype adds in video to net calls". 2005-12-01. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Messaging in an instant". 2001-09-09. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Bergfeld, Carlos (2008-04-17). "Facebook Chat: Reports of AIM's Death Greatly Exaggerated - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Kelly, Jon (24 May 2010). "Instant messaging: This conversation is terminated". BBC. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Carlson, Nicholas. "In The Biggest Blown Opportunity Ever, AOL Instant Messenger Has Utterly Collapsed". Business Insider. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Chat apps surpass SMS for the first time, study finds". 29 April 2013.

- Ling, Rich; Lai, Chih-Hui (2016-10-01). "Microcoordination 2.0: Social Coordination in the Age of Smartphones and Messaging Apps". Journal of Communication. 66 (5): 834–856. doi:10.1111/jcom.12251. ISSN 0021-9916.

- Horwitz, Josh (25 August 2015). "Why WhatsApp bombed in the US, while Snapchat and Kik blew up". Quartz. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "AIM has been discontinued as of December 15, 2017". help.aol.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017.

- "The rise of messaging platforms". The Economist, via Chatbot News Daily. 2017-01-22. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Business Use of Instant Messaging on the Rise, Email Still Primary Survey Finds". 2017-06-09. Archived from the original on 2024-08-06. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Third-party Discord app brings back MSN Messenger but there's a catch". Dexerto. 2024-04-05. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "A Brief History of Chat Services" (PDF). sameroom.io. 19 April 2023.

- "The best all-in-one messaging apps in 2024". zapier.com. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "WhatsApp Permanently Bans Users of Unofficial Clients".

- "AOL, Time Warner complete merger with FCC blessing". CNET.

- "Green light for AOL-Time Warner merger". ZDNET.

- "AOL wins instant messaging case". 2002-12-19. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Gates Adds His Voice To Instant Messaging". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Hicks, Matthew (2004-07-15). "Microsoft Opens IM Server to AOL, Yahoo". eWeek. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Microsoft, Yahoo connect IM services". CNET. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Bylund, Anders (2005-12-21). "Google buys 5 percent of AOL; Google Talk and AIM to chat it up". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Schwartz, Barry (2007-12-05). "Google Talk Meets AOL Instant Messager: Time Warner & Google Complete AIM Integration Deal". Search Engine Land. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Jabber gateway aims to link XMPP, SIMPLE". InfoWorld. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Claburn, Thomas. "EU mandated interoperable messaging not so simple: Paper". www.theregister.com. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- Jowitt, Tom (2024-03-13). "Meta Messaging Interoperability Whatsapp, Messenger". Silicon UK. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Text Messaging Apps Are Transforming Workplace Communications". TeleMessage. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Kashyap, Vartika. "Are Messaging Apps at Work Affecting Team Productivity?". learn.g2.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Sarkar, Advait; Rintel, Sean; Borowiec, Damian; Bergmann, Rachel; Gillett, Sharon; Bragg, Danielle; Baym, Nancy; Sellen, Abigail (2021-05-08), "The promise and peril of parallel chat in video meetings for work", Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–8, doi:10.1145/3411763.3451793, ISBN 978-1-4503-8095-9, S2CID 233987188, retrieved 2021-11-01

- instant messaging Archived February 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, NetworkDictionary.com.

- "Better Business IMs - Business Technology". Im.about.com. 2012-04-10. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- "Reader Questions IM Privacy at Work". Im.about.com. 2008-03-15. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- "Message in a bottleneck". CNET. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Oracle Buzzes with Updates for its Beehive Collaboration Platform". CMSWire. May 12, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- "IM Security Center". Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- "Why just say no to IM at work". Blog.anta.net. October 29, 2009. ISSN 1797-1993. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- Chris Christiansen and Rose Ryan, International Data Corp., "IDC Telebriefing: Threat Management Security Appliance Review and Forecast"

- Dredge, Stuart (2014-11-06). "How secure is your favourite messaging app? Today's Open Thread". the Guardian. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- "Secure Messaging Scorecard". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Saleh, Saad (2015). IM Session Identification by Outlier Detection in Cross-correlation Functions. Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS). doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3524.5602.

- Saleh, Saad (December 2014). Breaching IM Session Privacy Using Causality. IEEE Global Communications Conference (Globecom). doi:10.13140/2.1.1112.2244.

- Baran, Guru (2023-09-11). "Weaponized Telegram App Infected Over 60K Android Users". Cyber Security News. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Doffman, Zak. "No, Don't Quit WhatsApp To Use Telegram Instead—Here's Why". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- "Skype hauled into court after refusing to hand call records to cops". The Register. 26 May 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Risen, James; Poitras, Laura (28 September 2013). "N.S.A. Gathers Data on Social Connections of U.S. Citizens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- "A Primer on Metadata: Separating Fact from Fiction - Privacy By Design". Privacybydesign.ca. 2013-07-17. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- Grove, Jennifer (2014). Facebook Sued for Allegedly Intercepting Private Messages. Mobile World Congress. Retrieved from Cnet.com

- "Cisco WebEx Messenger: Enterprise Instant Messaging through a Commercial-Grade Multilayered Architecture" (PDF). Cisco.com. Retrieved 2015-10-11.

- Schneier, Bruce; Seidel, Kathleen; Vijayakumar, Saranya (11 February 2016). "Multi-Encrypting Messengers – in: A Worldwide Survey of Encryption Products" (PDF). Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Adams, David; Maier, Ann-Kathrin (6 June 2016). "Big Seven Study, open source crypto-messengers to be compared – or: Comprehensive Confidentiality Review & Audit: Encrypting E-Mail-Client & Secure Instant Messenger, Descriptions, tests and analysis reviews of 20 functions of the applications based on the essential fields and methods of evaluation of the 8 major international audit manuals for IT security investigations including 38 figures and 87 tables" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Cybersecurity 101: How to choose and use an encrypted messaging app". TechCrunch. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "Best WhatsApp Alternatives". Tuta. 24 February 2024. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- "ESG compliance report excerpt, Part 1: Introduction". Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- FINRA, Regulatory Notice 07-59, Supervision of Electronic Communications, December 2007

- ^ "Messaging App Usage Statistics Around the World". MessengerPeople. 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "11 New People Join Social Media Every Second (And Other Impressive Stats)". Archived from the original on 2018-01-30.

- "Most Popular Messaging Apps by Country". Similarweb.

- "Most Popular Messaging Apps: Top Messaging Apps 2021". Respond.io.

- "Viber usage spikes as pandemic strikes". The Philippine Star. 29 January 2021.

- "Viber expands foothold in the Philippines in 2021". BusinessMirror. 18 December 2021.

- "When chatting apps can be overwhelming". VnExpress International.

External links

| Instant messaging | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocols (comparison) |

| ||||||||

| Services |

| ||||||||

| Clients (comparison) |

| ||||||||

| Defunct | |||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

| Computer-mediated communication | |

|---|---|

| Asynchronous conferencing | |

| Synchronous conferencing | |

| Publishing | |

| Web syndication | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | |||||||||||||||

| Technology |

| ||||||||||||||

| Form | |||||||||||||||

| Media |

| ||||||||||||||

| Mobile phones | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile networks, protocols |

| ||||||

| General operation | |||||||

| Mobile devices |

| ||||||

| Mobile specific software |

| ||||||

| Culture | |||||||

| Environment and health | |||||||

| Law | |||||||