House numbering is the system of giving a unique number to each building in a street or area, with the intention of making it easier to locate a particular building. The house number is often part of a postal address. The term describes the number of any building (residential or commercial) with a mailbox, or even a vacant lot.

House numbering schemes vary by location, and in many cases even within cities. In some areas of the world, including many remote areas, houses are named but are not assigned numbers.

In many countries, the house number follows the name of the street; but in anglophone and francophone countries, the house number normally precedes the name of the street.

History

A house numbering scheme was present in Pont Notre-Dame in Paris in 1512. However, the purpose of the numbering was generally to determine the distribution of property ownership in the city, rather than for the purpose of organization.

In the 18th century the first street numbering schemes were applied across Europe, to aid in administrative tasks and the provision of services such as mail delivery. The New View of London reported in 1708 that "at Prescott Street, Goodman's Fields, instead of signs, the houses are distinguished by numbers". Parts of the Paris suburbs were numbered in the 1720s; the houses in the Jewish quarter in the city of Prague in the Austrian Empire were numbered in the same decade to aid the authorities in the conscription of the Jews.

Street numbering gained momentum in the mid-18th century, especially in Prussia, where authorities were ordered to "fix numbers on the houses ... in little villages on the day before the troops march in". In the 1750s and 60s, street numbering on a large scale was applied in Madrid, London, Paris, and Vienna, as well as many other cities across Europe. On 1 March 1768, King Louis XV of France decreed that all French houses outside of Paris affix house numbers, primarily for tracking troops quartered in civilian homes.

Due to the gradual development of house numbering and street addressing schemes, reform efforts occur periodically. For instance, some US cities started efforts to improve their schemes in the late 19th century.

Australia and New Zealand

In Australia and New Zealand, the current standard (Australia/New Zealand joint standard AS/NZS 4819:2011 – Rural & Urban Addressing) is directed at local governments that have the primary responsibility for addressing and road naming. The standard calls for lots and buildings on newly created streets to be assigned odd numbers (on the left) and even numbers (on the right) when facing in the direction of increasing numbers (the European system) reflecting already common practice. It first came into force in 2003 under AS/NZS 4819:2003 – Geographic Information – Rural & Urban Addressing. An exception may occur where the road forms part of the boundary between different council areas or cities. For example, Underwood Road in Rochedale South, part of which is divided between Logan City and the City of Brisbane.

Where a block of land, such as No. 9, is divided into parts, the sequence might go 7, 9, 9A, 11, 13. Conversely, should blocks of land be combined such as 51, 53, 55, the numbers might go 49, 51–55, 57. An older form of 9A is 9½.

In New South Wales and South Australia, the vast majority of streets were numbered when the land titles were created, with odd numbers assigned to houses on the right of the street when facing the direction along which numbers increase. There is no plan to reassign these numbers.

On some long urban roads (e.g., Parramatta Road in Sydney) numbers ascend until the road crosses a council or suburb boundary, then start again at 1 or 2, where a street sign gives the name of the relevant area – these streets have repeating numbers. In semi-rural and rural areas, where houses and farms are widely spaced, a numbering system based on tens of metres or (less commonly) metres has been devised. Thus a farm 2,300 metres (7,500 ft) from the start of the road, on the right-hand side would be numbered 230.

Walcha, in the New England district of northern New South Wales, has a unique numbering system which differs from the rest of the state. The town lies at the intersection of the Oxley Highway and Thunderbolts Way. All properties on east–west running streets have a 'W' or 'E' appended to the number signifying the property lies to the west (or east) of Thunderbolts Way. Similarly, in north–south running streets have an 'N' or 'S' appended to the house number signifying that the property lies north (or south) of the Oxley Highway.

Ballarat Central, Victoria, uses the US system of increasing house numbers by 100 after a major cross street. Streets are designated North or South depending upon their relative position to Sturt Street.

The number system will always start with No. 1 or No. 2 at the datum point of the street, with number 1 typically being on the left side of the street.

East Asia

Main articles: Japanese addressing system and Addresses in South Korea

In Japan and South Korea, a city is divided into small numbered zones. The houses within each zone are then labelled in the order in which they were constructed, or clockwise around the block. This system is comparable to the system of sestieri (sixths) used in Venice.

In Hong Kong, a former British colony, the British and European norm to number houses on one side of the street with odd numbers, and the other side with even numbers, is generally followed. Some roads or streets along the coastline may however have numbering only on one side, even if the opposite side is later reclaimed. These roads or streets include Ferry Street, Connaught Road West, and Gloucester Road.

Most mainland Chinese cities use the European system, with odd numbers on one side of the road and even numbers on the opposite side. In high-density old Shanghai, a street number may be either a hao ("号" hào) or nong ("弄" nòng/lòng), both of them being numbered successively. A hao refers a door rather than a building, for example, if a building with the address 25 Wuming Rd is followed by another building, which has three entrances opening to the street, the latter will be numbered as three different hao, from 27 to 29 Wuming Rd.

A nong, sometimes translated as "lane", refers to a block of buildings. So if in the above example the last building is followed by an enclosed compound, it will have the address "lane 31, Wuming Rd". A nong is further subdivided in its own hao, which do not correlate with the hao of the street, so the full address of an apartment within a compound may look like "Apartment 5005, no. 7, lane 31, Wuming Rd".

In Taiwan, the European system is used in cities, and is mostly same as the cases of mainland Chinese cities and Hong Kong. Longer roads are usually divided into several sections to prevent the road having too many numbers (normally more than 1000). In rural areas, village or settlement name is used in house numbering, where numbering norms are not certain. A xiang ("巷" xiàng, translated as "lane") indicates a branch from a main road; and a nong ("弄" nòng/lòng, translated as "alley") indicates a branch from a xiang. For many reasons such as new establishment of buildings or several apartments in a building, the zhi ("之" zhī, normally simply translated as a hyphen, "–") is used.

Southeast Asia

The most common street address formats in Vietnam are:

- A number followed by the street name, for example "123 đường Lê Lợi". This is the most basic, most common format.

- A number with an alphabetic suffix: "123A đường Lê Lợi", "123B đường Lê Lợi", etc. This format occurs when a property is numbered 123 but later subdivided into two houses with different addresses.

- If the house lies on an hẻm/ngõ (alley), the alley number is combined with the house number: for example, in "123/3 đường Lê Lợi", 123 is the alley's address, and 3 is the house number on that alley.

- More complex house numbers may occur on alleys that branch from other alleys or properties on alleys are subdivided, for example "123/3E đường Lê Lợi" or "123/3/5B đường Lê Lợi". An extreme example would be "7/14/12/3/23a đường 182", which is located on 3rd alley off 12th alley off 14th alley off 7th alley off 182nd street.

Another scheme is based on residential areas called cư xá. A cư xá is addressed by house number, road, and cư xá, for example "123 đường số 4 cư xá Bình Thới". Some localities still use an older address format based on neighborhood (khu phố): for example, in "7A/34 Tô Hiến Thành", 7A is the neighborhood number. This confusing format is being gradually phased out in favor of the more modern formats above.

West Asia

Generally in Iran and especially in the capital Tehran odd numbers are all on one side and the even numbers opposite along streets. Infrequently, this style confuses people because this is not how it works everywhere in the city and sometimes the numbers get intertwined with each other. In the rural parts, some houses have no number at all and some have their owner's details as the number instead. In some cases, using the number 13 is skipped replacing it with equivalents such as: 12+1 or 14−1.

Northern and Western Europe

In Europe the most common house numbering scheme, in this article referred to as the "European" scheme, is to number each plot on one side of the road with ascending odd numbers, from 1, and those on the other with ascending even numbers, from 2 (or sometimes 0). The odd numbers are usually on the left side of the road, looking in the direction in which the numbers increase.

Where additional buildings are inserted or subdivided, these are often suffixed a, b, c, etc. (in Spain, France and Afragola until 2001, bis, ter, quater, quinquies etc.). Where buildings are later combined, one of the original numbers may be used, the numbers may be combined ("13/15"), or the numbers may be used as a given range (e.g. "13–17"; not to be construed as including the even numbers 14 and 16). Buildings with multiple entrances may have a single number for the entire building or a separate number for each entrance.

Where plots are not built upon gaps may be left in the numbering scheme or marked on maps for the plots. If buildings are added to a stretch of old street the following may be used rather than a long series of suffixes to the existing numbers: a new name for a new estate/block along the street (e.g. 1–100 Waterloo Place/Platz, Sud St..); a new road name inserted along the course of a street either with or without mention of the parent street; unused numbers above the highest house number may be used (although rarely as this introduces confusing discontinuity), or the upper remainder of the street is renumbered.

Other local numbering schemes are also in use for administrative or historic reasons, including clockwise and anti-clockwise numbering, district-based numbering, distance-based numbering, and double numbering.

France

The first record of a house numbering system in Paris dates to the 15th century. On March 1, 1768, King Louis XV decreed that all houses outside of Paris were to be assigned a number to help locate the soldiers residing in civilian houses. On February 4, 1805, Napoleon I announced that in Paris for house numbering a distinction should be made between even numbers (on the right side) and odd numbers (on the left side); the direction of the streets is oriented from upstream to downstream for streets parallel to the Seine, and from the banks to the north and south for streets oblique or perpendicular to the Seine. Such a system quickly became common in large cities across France.

A ruling in 1994 obliged French communes with a population of 2,000 or more to number their houses. Sequential numbering, common in cities, mimics the system used in Paris. But many small villages used the numbering which takes a central village point — often the town hall — and works outward (a house that is 200 metres along the road from point zero will be numbered 200, its nearest neighbour, perhaps 270 metres from the centre, becomes number 270, etc.)

Finland

The Finnish numbering system incorporates solutions to the problems which arose with mass urbanization and increase in building density. Addresses always are formatted as street name followed by street address number. With new, infill building, new addresses are created by adding letters representing the new ground level access point within the old street address, and if there are more apartments than ground level access points, a number added for the apartment number within the new development. The original street numbering system followed the pattern of odd numbers on one side and even numbers on the other side of the street, with lower numbers towards the center of town and higher numbers further away from the center.

The infill numbering system avoids renumbering the entire street when developments are modified. For example, Mannerheimintie 5 (a large mansion house on a large city plot) was demolished and replaced with 4 new buildings each with 2 stairwells all accessible from Mannerheimintie. The 8 new access stairwells are labelled A B C D E F G and H (each with the letter visible above the stairwell). Each stairwell has 4 apartments on 5 floors, so the new development has 160 new addresses in all running from Mannerheimintie 5 A 1 through to Mannerheimintie 5 H 160. The opposite example is where old, narrow buildings have been combined; Iso Roobertinkatu 36, 38 and 40 were demolished in the 1920s and the new building has the address Iso Roobertinkatu 36–40.

In the rural parts of Finland, a variant of this method is used. As in towns, odd and even numbers are on opposite sides of the road, but many numbers are skipped. Instead, the house number indicates the distance in tens of metres from the start of the road. For example, "Pengertie 159" would be 1590 metres from the place where Pengertie starts.

Netherlands

When more buildings are constructed than numbers were originally allotted, discontinuity of numbering is avoided by giving multiple adjacent buildings the same number, with a letter suffix starting at "A". The "Bis" suffix is used occasionally. Each house or apartment can be uniquely identified by a combination of a postcode, a street number and a suffix. Apartments within the same building can be distinguished various ways: by assigning each apartment their own street number, by assigning a simple prefix (generally a letter) or by assigning a complex prefix that takes into account both the floor and the apartment on the floor (e.g. B3). In Haarlem, Netherlands, red numbers are used for upstairs apartments.

Portugal

In Portugal, the European scheme is most commonly used. However, in Porto and several other cities in the Portuguese Northern region, as well as in the Cascais Municipality (near Lisbon), houses are numbered in the North American style, with the number assigned being proportional to the distance in meters from the baseline of the street.

Lisbon numbering is European and furthermore 'from the river, odd numbers left'. Because the Tagus borders Lisbon on the south and the east, this means that north–south streets are numbered low from the south, and east–west streets are numbered low from the east.

In many new planned neighborhoods of Portugal houses and other buildings are identified by a lote (plot) number without reference to their street. This is in law the número de polícia, which literally means police's number – the police formerly assigned the numbers rather than the town hall. The lote is the construction plot number used in the urban plan, a consecutive number series applies to a broad neighborhood. In theory and in most cases, the use of a lote number system is provisional, being replaced by a traditional street number system some time after the neighborhood is built and inhabited. In some neighborhoods, lote numbers are kept for many years, some never being replaced by street numbers.

The relatively new planned neighborhood of Parque das Nações in Lisbon has also a different numbering scheme: each building is referred by its plot, parcel, and building (in Portuguese: lote, parcela, prédio).

United Kingdom

The European system is most widely used. The odd numbers will typically be on the left-hand side as seen in the direction of increasing numbers (most commonly with the lowest numbers at the end of the street closest to the town or village centre). Intermediate properties usually have a number suffixed A, B, C, etc., much more rarely instead being given a half number, e.g. the old police station at 20+1⁄2 Camberwell Church Street. It is extremely rare for a property (built next to no. 2 after the street had been numbered) to be zero (0) or named Minusone; in 2013 researchers found these instances once in Middlesbrough and once in Newbury. In 2022, starting to type "0," into the Royal Mail postcode search revealed Middlesbrough had four listed properties, whilst Birmingham, Ellesmere Port, Lincoln and London have one each. In many rural streets, significantly built alongside before 1900, houses remain named and unnumbered.

In some places, particularly when open land, a river or a large church fronts one side, all plots on one side of a street are numbered consecutively. Such a street if modern and long is more likely to be numbered using odd numbers, starting at 1. Along oldest streets, numbering is usually clockwise and consecutive: for example in Pall Mall, some new towns, and in many villages in Wales. This often also applies to culs-de-sac and standalone terraces. For instance, 10 Downing Street, the official home of the Prime Minister, is next door to 11 Downing Street. Houses which surround squares, as well as market places, are usually numbered consecutively clockwise.

In the early to mid 19th century numbering of long urban streets commonly changed from clockwise (strict consecutive) to odds facing evens, particularly when roads were extended into new suburbs. Where this took place it presents a street-long pitfall to researchers using historic street directories and other records. A very rare variation may be seen where a high street (main street) continues from a less commercial part – a road which breaks the UK conventions by not starting at 1 or 2. On one side of the main road between Stratford and Leytonstone houses up to no. 122 are "Leytonstone Road". The next house is "124 High Road, Leytonstone".

In some villages, a single numbering system covers the entire settlement, especially in rural areas without formal street names. In this case the house number directly precedes the village name in addresses. This often coexists with newer developments within the same village that use street names (e.g., "58 Dorfield" alongside "3 Church Close, Dorfield"), although to avoid confusion the older houses may eventually gain street names of their own while keeping their numbers ("58 Axtley Road, Dorfield").

Developers may avoid the number 13 for house numbering as in Iran, because that number is considered by some to be unlucky.

Blocks of flats (apartments) are treated in two ways:

- Flats numbered individually as part of the street. A lintel will typically be embossed or metalled "1–24 Acacia Avenue" or "Flats 1–24 Acacia Avenue".

- Flats numbered within a building. The building retains its own number (or name) on the street e.g. "Flat 24, 1 Acacia Avenue" or increasingly as commonly: "Apartment 9D, Newhouse Court, 1 Acacia Avenue". Outside the number of flats is discreetly shown or not revealed. Where flats are lettered, this can also be indicated by appending the letter to the building number: "Flat D, 1 Acacia Avenue" may also be "1D Acacia Avenue" (generally only one of these formats will be officially used).

- In some parts of Scotland, particularly Aberdeen and Dundee, flats in tenement blocks may be numbered as follows; "Flat 3/L, 1 Acacia Avenue". In this numbering system 3 refers to the floor (with G or 0 being used for the ground floor) and L or R indicating whether the flat is on the left or right from the entrance of the block.

Marking of numbers

In the UK street numbering and street signposts vary across local authorities. Numbering plates (or similar) are overwhelmingly at the discretion of house owners.

In the UK fanlights in front doors were introduced in the 1720s in which the house number may be engraved. Contemporary architecture and modern house building techniques see alternatively acrylic, aluminium, or glass, ceramic, brass, slate, or stone used.

Southern Europe

Italy

Italy mostly follows the European scheme described above but there are some exceptions, generally for historical reasons.

In Venice, houses are numbered within six named series (one per sestiere district). Similarly, small villages in rural areas may also occasionally use a single progressive series for all house numbers.

In Genoa, Savona and Florence houses are marked with black (sometimes blue in Florence) numbers; businesses are usually (but not always) given red numbers, giving up to two distinct, numerically overlapping series per street. Those of businesses are denoted in all other writing (documents, online directories, etc.) by the addition of the letter "r" for rosso (e.g. "Via dei Servi 21r").

Turkey

In most of Turkey, currently the European house numbering scheme is applied. The Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality introduced new house numbering and street signs in 2007 by two official designers.

-

House number in Foça

House number in Foça

Central and Eastern Europe

In Central and Eastern Europe, with some exceptions, houses are typically numbered in the European style. Many streets, however, use the "boustrophedon" system.

-

House number in Vienna

House number in Vienna

-

Polish house number

Polish house number

-

A typical Prague combination: red conscription number above, blue orientation number below

A typical Prague combination: red conscription number above, blue orientation number below

-

House number 26a on Kurfürstendamm in Berlin

Austria

A double numbering system has been used, similar to the system in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, which also were formerly parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Czech Republic and Slovakia

In some Czech and Slovak cities and settlements, two numbering systems are used concurrently.

The basic house number is the "old" or "conscription number" (Czech: popisné číslo, Slovak: súpisné číslo). The conscription number is unique within the municipal part (a village, a quarter, mostly for one cadastral area) or within a whole small municipality.

For makeshift and recreational buildings in the Czech Republic, "registration number" (evidenční číslo) from a separate number series is used instead of the descriptive number. Typically, this number begins with zero or with the letter "E", or has different colour, or contains words like nouzová stavba ("makeshift structure") or chata ("weekend house"), etc. In Slovakia, the provision on the use of these numbers was repealed by law 517/1990 Zb., and the numbers repealed by decree 347/1997 Z. z., according to its § 8 these numbers will be replaced with conscription numbers until December 31, 1998.

In some settlements where streets have names (mostly in cities), "new" or "orientational numbers" (Czech: orientační číslo, Slovak: orientačné číslo) are also used concurrently. The orientational numbers are arranged sequentially within the street or square. If the building is on a corner or has two sides, it can have two or more orientation numbers, one for each of the adjacent streets or squares. Solitary houses distant from named streets often have no orientation number. In some places, the name of a small quarter is used instead of a street name. If there is a new building between two older numbered ones, the orientation number is distinguished with an additional lower case letter (for example, the sequence could be 5, 7, 9, 9a, 9b, 9c, 11, 13). In the 1930–1950s in Brno, lower case letters were used for separate entrances of modern block houses perpendicular to the street.

Either number may be used in addresses. Sometimes, businesses will use both numbers to avoid confusion, usually putting the descriptive (or registration) number first: "Hlavní 20/7". The two (or three) types of numbers are commonly distinguished by colour of the sign. Each municipality can have its own traditional or official rules and colours. In Prague and many other Bohemian cities, descriptive numbers are red, orientation numbers are blue and "evidential" numbers are green or yellow or red. In many Bohemian municipalities, descriptive numbers are blue, black, or are not unified. In Brno and some Moravian and Slovak cities, descriptive numbers are white-black signs, orientation numbers are red-white signs. Many cities and municipalities have different rules.

Formerly, Roman numerals signifying the city district were added to the conscription number: e.g. "125/III" means conscription number 125 in district number III (in Prague, this was Malá Strana). Roman numerals were used both in cities and in village municipalities with more settlements. Nowadays, the name of the settlement is preferred instead of Roman numerals.

The first conscription numbering was ordered by Maria Theresa in 1770 and implemented in 1770–1771. The series was given successively as the soldiers went through the settlement describing houses with numbers. Thereafter, every new house was allocated the next number sequentially, irrespective of its location. Most villages still use their original number series from 1770 to 1771. In cities, houses have been renumbered once or more often to be sequential – the first wave of renumbering came in 1805–1815. In 1857, the Austrian Emperor allowed a new system of numbering by streets. This new system was introduced in the biggest cities (Prague, Brno) in the 1860s. In 1884, land registration books were introduced and they used the old (conscription) numbers as a permanent and stable identifier of buildings. The new (orientation) numbers continue to be used concurrently.

Germany

In Germany, the European scheme (ascending odd/even numbers, see above) is usually used. In most cases, the numbers increase in the direction away from the town/city centre. Some places use a clockwise scheme for historical reasons, called Hufeisennummerierung ("horseshoe numbering") due to the progression of the numbers. This includes Berlin, parts of Hamburg and some other towns in northern Germany.

In some older streets in northern and eastern Germany, mainly in the former Kingdom of Prussia and adjoining areas, including parts of Berlin and Hamburg, the "horseshoe" numbering system (counter-clockwise "boustrophedon"-style numbering) was used for the numbering of new streets up until the 1920s, after which the European system was introduced for new streets.

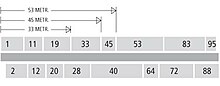

Under the horseshoe numbering scheme, starting from one end, the buildings on the right side of the street were numbered sequentially from the near end to the far end of the street. The next number was then assigned to the last building on the left, opposite side of the street, the following numbers sequentially doubling back along the left side of the street. The building with the highest number would be the first on the left side, facing building number 1 across the street. The horseshoe numbering system remains in use in older streets in many German cities, notably Berlin, although newer adjoining streets may use modern European numbering. Kurfürstendamm in Berlin is a well-known example of a street where the horseshoe numbering scheme is still in use, although the numbering today starts with 11 at Breitscheidplatz, with number 237 across the street being the highest number.

Very small villages sometimes number all buildings in the village sequentially according to their date of construction, and independent of the street they are on. However, this scheme is being phased out because it makes it hard to find a building by its address.

Former Soviet Union

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In Russia and many other former USSR countries, the European style is generally used, with numbers starting from the end of the street closest to the town center. Buildings or plots at street intersections may be assigned a composite number, which includes the number along the intersecting street separated by a slash (Russian: дробь), like in Нахимова, 14/41 (14 is the number along Nakhimova street and 41 is the number along intersecting street).

The odd numbers are usually on the left side of the road, looking in the direction in which the numbers increase; though in some cities (including Saint Petersburg) the odd numbers are on the right side. Some cities (for example, Nizhniy Novgorod) have mixed numbering: odd numbers on the right in some parts of the city and on the left in others.

Soviet era housing districts (microdistricts) often have a complicated network of access lanes thought too small to merit their own names. Buildings in these lanes are ascribed to larger streets which may be quite far from their location; a building placed along a street may sometimes be ascribed to another street, which sometimes makes finding a building by its address a challenging task.

In some cities, especially hosting large scientific or military research centers in Soviet times, the numbering might be different: houses may have numbers related to the block rather than the street, thus 12-й квартал, дом 3 (Block 12, House 3), similar to the Japanese and Korean systems. Aktau is one example of this.

When a numbered plot contains multiple buildings, they are assigned an additional component of the street address, called корпус (building), which is usually a sequentially assigned number unique within the plot (but sometimes contains letters as in 15а, 15б, 15в and so on). So, a Russian street address may look like Московское шоссе, дом 23, корпус 2 (Moscow Highway, plot 23, building 2), or улица Льва Толстого, дом 14Б (Leo Tolstoy Street, plot 14, building B).

On very long roads in suburban areas, a kilometer numbering system also may be used (like Australian rural numbering system). For example, 9-й км Воткинского шоссе (9th kilometer of Votkinsk Highway), and Шабердинский тракт, 7-й км (7th kilometer of Shaberdy Road).

-

In July 2010, after part of the existing street in Kyiv had been split off and renamed, the buildings got both new street names and new numbers.

In July 2010, after part of the existing street in Kyiv had been split off and renamed, the buildings got both new street names and new numbers.

-

Composite house numbers on street intersection, Veliky Novgorod

Composite house numbers on street intersection, Veliky Novgorod

Latin America

In Latin America, some countries, like Mexico and Uruguay, use systems similar to those in Europe. Houses are numbered in ascending order from downtown to the border of the city. In Mexico, the cities are usually divided in Colonias, which are small or medium areas. The colonia is commonly included in the address before the postal code. Sometimes when houses merge in a street or new constructions are built after the numbering was made, the address can become ambiguous. When a number is re-used, a letter is added for the newer address. For example, if there are two 35s, one remains as "35", and the second one becomes "35A" or "35Bis".

It is sometimes common in remote towns or non-planned areas inside the cities, that the streets do not have any name and the houses do not have numbers. In these cases, the address of the houses are usually the name of a person or family, the name of the area or town, or Dirección Conocida ("known address"), which means that the house of the family is known by almost all the community. This kind of addressing is only used in remote towns or small communities near highways. For people living near highways or roads, the usual address is the kilometer distance of the road in which the house is established; if there is more than one address, some references might be written or the Dirección Conocida may be added.

In Uruguay, most house numbering starts at a high number among the hundreds or the thousands. The system is similar to the French-Spanish one: when a house is divided the term 'bis' is added with the difference that no single term designates the third: when a house is divided or added between another the term 'bis' is repeated as many divisions have been made or houses added in between, for example '3217 bis bis' corresponds to the third house from the 3217th, and so on. When many houses are merged the lowest number is used, leaving the in-between numbers missing. Also there are cases when no number is assigned; this occurs mostly in peripheral areas inside the cities. Low house numbering occurs in small locations, and in balneary areas houses are designated by name rather than number.

In countries like Brazil and Argentina, a scheme is used also for streets in cities, where the house number is the distance measured in meters from the house to the start of the street. In Venezuela, houses, buildings, and streets have names instead of numbers.

Colombia

The urban addresses in the cities of Colombia are based on a numerical model, technically designed in a similar way to a Cartesian plane, with a grid (orthogonal) and metric layout in each block; where the central (urban) point is number 1, which represents the intersection between street 1 and street 1; Urban roads are basically classified with the names: Calle, Carrera, Diagonal, Transversal and Avenida (Avenida Calle and Avenida Carrera); It is an urban guidelines format, with characteristics: standard, understandable, functional, flexible and for general use in all urban populations in Colombia.

In most of the names of urban roads, they are located and classified in the same way and direction of orientation, from south to north and from east to west; but in few cities the concepts of streets for races, or races for streets, are reversed.

The Streets in North and Trajectory (line), Street Street, Orientation and Cross the Races Street The Streets and Located Towards The South, Street 1 (Central Zone), The complementary form in the name of South, instead, calls towards the; north no complement is made in denomination; This applies in most cities, but in some towns the opposite applies (example: …, Calle 3, Calle 2, Calle 1, Calle 1 Sur, Calle 2 Sur, Calle; 3 Sur,…).

The races run parallel from east to west and the trajectory (line) of each race is from south to north. The races that are heading east, in most cases, are complemented with the name of the east cardinal point (Example: ..., Race 3 East, Race 2 East, Race 1 East, Race 1, Race 2, Race 3) , in other cities the opposite applies (Carrera 3, Carrera 2, Carrera 1, Carrera 1 West, Carrera 2 West, Carrera 3 West).

In addition to the runs and streets, there are diagonals and transversals.

The diagonals run linearly from east to west, like the streets, but obliquely to the sequence of the streets and interspersed between them.

The transversals run linearly from south to north, like the races, but obliquely to the sequence of the races and interspersed between them.

The main roads are called Avenues; If it is a street it is called Avenida Calle, if it is a race it is called Avenida Carrera, with the street number (example: Avenida Carrera 68) and it is also usually called with a symbolic name (example: Avenida Rojas).

The roads are numbered consecutively, in some cases the number is complemented by the sequence of letters of the alphabet or the simple adjective bis, to indicate that it immediately follows the same number already used (example: Street 1, Street 2, Street 3, Calle 3 Bis, Calle 4, Calle 4A, Calle 4B, Calle 4B Bis, Calle 4C, ..., Calle 5, ...).

North America

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "House numbering" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the United States and Canada, streets are usually numbered with odd on one side and even on the other. The specific ordering of the numbers varies based on the policies of the local municipality. Generally, three different systems exist:

- Streets may be numbered strictly sequentially, starting with 1 at the start of the street, and continuing in order skipping no numbers until the end. In these cases, if additional addresses are needed to be assigned to new buildings or buildings contain individual apartments, fractional house numbers may be used, or letter suffixes may be appended to the house number.

- Streets may be numbered from the most recent intersection. In these cases, numbers progress sequentially from each intersection, but skip to the next set of numbers at each cross street, usually in sets of even 100s. Thus, the first block on a street may start at 1, and continue up until the next block, when they start at 100, then 200, and so on. A block or other segment of a street that has 100 numbers allotted to it under such a scheme is called a "hundred block," e.g., "the 1400 block" if the numbers are 1400–1499.

- Habitable structures in alleys may vary in numbering, either being numbered individually to a named alley, or being numbered to the street on the side that structure is on, possibly with a fractional or letter suffix.

- Streets may be numbered based on distances, where the house number is based on some mathematical formula according to the distance from the start of the numbering system. As an example, a numbering system can provide 1000 addresses per mile, 500 on each side of the street, amounting to an address pair (odd and even) every 10.56 feet. Thus, a property numbered 1447 may be approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometres) from the beginning point for the numbering system.

Even within these systems, there are also two ways to define the starting point for the numbering system. Some places will start the numbering system at the start of the street itself. Other places will define a numbering system based on a defined point or line, such as a municipal or county boundary, a physical barrier separating a community's sides such as a body of water, or a defined intersection near the center of the municipality, with numbers increasing generally as one gets further from the baseline, regardless of where streets start or stop. Some communities use a railroad through a community as the numerical starting point. Addresses in many cites using a defined point or line roughly follow Cartesian coordinates.

History of address numbering in US

Many cities and civic groups have made efforts to improve street name and numbering schemes, such as Boston in 1879, Chicago in 1895, and Nashville in 1940 among others. The street grid system of New York City, with its numbered streets and avenues, is attributed to the Commissioners' Plan of 1811. In Chicago, Edward P. Brennan worked in his spare time over 8 years to create a proposal to increase the efficiencies of the street name and addressing system, which was largely approved in 1909. In Hollywood, Florida, Benjamin Israel worked for two and a half years to change three street names in the historic black district of Liberia from those that listed the names of Confederate soldiers in the American Civil War - Lee Street, Forrest Street, and Hood Street - to the names of Liberty Street, Freedom Street, and Hope Street. A local business owner had to supply the $20,000 funding to implement the change. There are places in West Virginia which did not have named streets or addresses until at least 2013. After Verizon was caught inflating prices in 2002, Verizon reached an agreement with the state to supply $15 million to create at least 450,000 new street addresses.

House numbering can be overhauled when a single addressing scheme replaces multiple local addressing schemes. An example from the 19th century is the house renumbering that occurred as part of the Georgetown street renaming in Washington, D.C. In the 20th century, this occurred in places such as the New York borough of Queens and Arlington County, Virginia.

See also

- Geocode

- Human geography

- Numbered streets, which often form an integrated system with house numbering

- Slum

References

- "The Numbering of Houses" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 July 1898. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Roy Porter (1998). London: A Social History. Harvard University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-674-53839-9.

- Tantner, Anton (31 December 2009). "Addressing the Houses: The Introduction of House Numbering in Europe". Histoire & Mesure. XXIV (XXIV-2): 7–30. doi:10.4000/histoiremesure.3942. ISSN 0982-1783.

- Tantner, Anton (2009). "Addressing the Houses: The Introduction of House Numbering in Europe". Histoire & Mesure. XXIV (2): 7–30. doi:10.4000/histoiremesure.3942. S2CID 142666167. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Rose-Redwood, Reuben S. (1 April 2008). "Indexing the great ledger of the community: urban house numbering, city directories, and the production of spatial legibility". Journal of Historical Geography. 34 (2): 286–310. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2007.06.003.

- Rose-Redwood, Reuben (2009) . "Indexing the Great Ledger of the Community: Urban House Numbering, City Directories, and the Production of Spatial Legibility". In Berg, Lawrence D.; Vuolteenaho, Jani (eds.). Critical Toponymies: The Contested Politics of Place Naming. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7546-7453-5. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ American Society of Planning Officials (April 1950). "Street Naming and House Numbering Systems". American Planning Association. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

Information Report No. 13

- "AS/NZS 4819:2011 Rural and urban addressing".

- "ICSM - Addressing". Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- "Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895". National Library of Australia. 13 October 1907. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- "Street Addressing Working Group and the National Street Addressing Standard" Archived 11 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Intergovernmental Committee on Survey and Mapping. 19 March 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- "House number". hk-place.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- Gibson, Victoria (24 August 2022). "Why were the French so suspicious of street numbering?". connexionfrance.com.

- "Napoleon and the Numbering of the Streets - Napoléon Cologne le Blog". blog.napoleon-cologne.fr. 17 September 2021.

- "The countryside catches up with Napoleon". The Economist.

- Soares, Marisa (22 November 2012). "Caiu o muro que dividia o Parque das Nações". PÚBLICO.

- "Falsehoods programmers believe about addresses". www.mjt.me.uk.

- "Royal Mail Find An Address". 17 November 2022.

- Bowlby, Chris. "Would you buy a number 13 house?". BBC News. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- The Fanlight Number Company, 19 July 2009. http://www.fanlightnumbers.co.uk/history.html

- Example of house numbers in Sistiana, Italy "Portopiccolo ha già il suo indirizzo: Sistiana 231 per le case, negozi al 232". Il Piccolo. 20 January 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "Istanbul's red signs, Kelebek (June 16, 2007); in Turkish.

- Wittstock, Bernhard (2011). Ziffer Zahl Ordnung. Die Berliner Hausnummer von den Anfängen Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts bis zur Gegenwart im deutschen und europäischen Kontext. Berlin.

- "Drochtersen hat ein Problem: Das große Durcheinander mit den Hausnummern" (in German). Hamburger Abendblatt. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Caravia, Antonio (1867). Colección de leyes, decretos y resoluciones gubernativas, tratados tratados internacionales, acuerdos del Tribunal de apelaciones y disposiciones de carácter permanente de la República Oriental del Uruguay (HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY 24 December 1915 LATIN AMERICAN PROFESSORSHIP FUND. ed.). Montevideo: Imp. a vapor de LA TRIBUNA. p. 278. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Addressing and Street Naming Guidelines and Procedures, from the Montgomery County (Md.) Planning Department and the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission

- Ordinance No. 2005-01 Archived 10 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Scott County, Virginia

- Mask, Deirdre (2020). The Address Book. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 257–258. ISBN 9781250134790.

- "Rationalization of Streets". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. 2005. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Mask, Deirdre (2020). The Address Book. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 175–189. ISBN 9781250134790.

- Mask, Deidre (February 2013). "Where the Streets Have No Name". www.theatlantic.com. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- In Georgetown, some streets have been renamed again and again, The Washington Post, August 31, 2019

- Here's the History of Why Queens Street Names are So Confusing, NY1, November 5, 2018

- The Renaming of Arlington Streets, Arlington Historical Society

Further reading

- Mask, Deirdre (2020). The Address Book. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 9781250134790.

- Tantner, Anton (2015). House Numbers: Pictures of a Forgotten History. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780235189.

External links

Media related to House numbers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to House numbers at Wikimedia Commons