| The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (May 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Voting | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Balloting

|

||||||||

Electoral systems

|

||||||||

Voting strategies

|

||||||||

Voting patterns and effects

|

||||||||

Electoral fraud and prevention

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

Vote counting is the process of counting votes in an election. It can be done manually or by machines. In the United States, the compilation of election returns and validation of the outcome that forms the basis of the official results is called canvassing.

Counts are simplest in elections where just one choice is on the ballot, and these are often counted manually. In elections where many choices are on the same ballot, counts are often done by computers to give quick results. Tallies done at distant locations must be carried or transmitted accurately to the central election office.

Manual counts are usually accurate within one percent. Computers are at least that accurate, except when they have undiscovered bugs, broken sensors scanning the ballots, paper misfeeds, or hacks. Officials keep election computers off the internet to minimize hacking, but the manufacturers are on the internet. They and their annual updates are still subject to hacking, like any computers. Further voting machines are in public locations on election day, and often the night before, so they are vulnerable.

Paper ballots and computer files of results are stored until they are tallied, so they need secure storage, which is hard. The election computers themselves are stored for years, and briefly tested before each election.

Despite the challenges to the U.S. voting process integrity in recent years, including multiple claims by Republican Party members of error or voter fraud in 2020 and 2021, a robust examination of the voting process in multiple U.S. states, including Arizona (where claims were most strenuous), found no basis in truth for those claims. The absence of error and fraud is partially attributable to the inherent checks and balances in the voting process itself, which are, as with democracy, built into the system to reduce their likelihood.

Manual counting

Manual counting, also known as hand-counting, requires a physical ballot that represents voter intent. The physical ballots are taken out of ballot boxes and/or envelopes, read and interpreted; then results are tallied. Manual counting may be used for election audits and recounts in areas where automated counting systems are used.

Manual methods

One method of manual counting is to sort ballots in piles by candidate, and count the number of ballots in each pile. If there is more than one contest on the same sheet of paper, the sorting and counting are repeated for each contest. This method has been used in Burkina Faso, Russia, Sweden, United States (Minnesota), and Zimbabwe.

A variant is to read aloud the choice on each ballot while putting it into its pile, so observers can tally initially, and check by counting the piles. This method has been used in Ghana, Indonesia, and Mozambique. These first two methods do not preserve the original order of the ballots, which can interfere with matching them to tallies or digital images taken earlier.

Another approach is for one official to read all the votes on a ballot aloud, to one or more other staff, who tally the counts for each candidate. The reader and talliers read and tally all contests, before going on to the next ballot. A variant is to project the ballots where multiple people can see them to tally.

Another approach is for three or more people to look at and tally ballots independently; if a majority agree on their tallies after a certain number of ballots, that result is accepted; otherwise they all re-tally.

A variant of all approaches is to scan all the ballots and release a file of the images, so anyone can count them. Parties and citizens can count these images by hand or by software. The file gives them evidence to resolve discrepancies. The fact that different parties and citizens count with independent systems protects against errors from bugs and hacks. A checksum for the file identifies true copies. Election machines which scan ballots typically create such image files automatically, though those images can be hacked or be subject to bugs if the election machine is hacked or has bugs. Independent scanners can also create image files. Copies of ballots are known to be available for release in many parts of the United States. The press obtained copies of many ballots in the 2000 Presidential election in Florida to recount after the Supreme Court halted official recounts. Different methods resulted in different winners.

When manual counts happen

The tallying may be done at night at the end of the last day of voting, as in Britain, Canada, France, Germany, and Spain, or the next day, or 1–2 weeks later in the US, after provisional ballots have been adjudicated.

If counting is not done immediately, or if courts accept challenges which can require re-examination of ballots, the ballots need to be securely stored, which is problematic.

Australia federal elections count ballots at least twice, at the polling place and, starting Monday night after election day, at counting centres.

Errors in manual counts

Hand counting has been found to be slower and more prone to error than other counting methods.

Repeated tests have found that the tedious and repetitive nature of hand counting leads to a loss of focus and accuracy over time. A 2023 test in Mohave County, Arizona used 850 ballots, averaging 36 contests each, that had been machine-counted many times. The hand count used seven experienced poll workers: one reader with two watchers, and two talliers with two watchers.

The results included 46 errors not noticed by the counting team, including:

- Caller called the wrong candidate, and both watchers failed to notice the incorrect call

- Tally markers tried to work out inconsistencies while tallying

- Tally markers marked a vote for an incorrect candidate and the watchers failed to notice the error

- Caller calling too fast resulted in double marking a candidate or missed marking a candidate

- Caller missed calling a vote for a candidate and both watchers failed to notice the omission

- Watchers not watching the process due to boredom or fatigue

- Illegible tally marking caused incorrect tally totaling

- Enunciation of names caused incorrect candidate tally

- Using incorrect precinct tally sheets to tally ballots resulted in incorrect precinct level results.

Similar tallying errors were reported in Indiana and Texas election hand counts. Errors were 3% to 27% for various candidates in a 2016 Indiana race, because the tally sheet labels misled officials into over-counting groups of five tally marks, and officials sometimes omitted absentee ballots or double-counted ballots. 12 of 13 precincts in the 2024 Republican primary in Gillespie County, TX, were added or written down wrong after a hand count, including two precincts with seven contests wrong and one with six contests wrong. While the Texas errors were caught and corrected before results were finalized, the Indiana errors were not.

Average errors in hand-counted candidate tallies in New Hampshire towns were 2.5% in 2002, including one town with errors up to 20%. Omitting that town cut the average error to 0.87%. Only the net result for each candidate in each town could be measured, by assuming the careful manual recount was fully accurate. Total error can be higher if there were countervailing errors hidden in the net result, but net error in the overall electorate is what determines winners. Connecticut towns in 2007 to 2013 had similar errors up to 2%.

In candidate tallies for precincts in Wisconsin recounted by hand in 2011 and 2016, the average net discrepancy was 0.28% in 2011 and 0.18% in 2016.

India hand tallies paper records from a 1.5% sample of election machines before releasing results. For each voter, the machine prints the selected candidate on a slip of paper, displays it to the voter, then drops the slip into a box. In the April–May 2019 elections for the lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha, the Election Commission hand-tallied the slips of paper from 20,675 voting machines (out of 1,350,000 machines) and found discrepancies for 8 machines, usually of four votes or less. Most machines tally over 16 candidates, and they did not report how many of these candidate tallies were discrepant. They formed investigation teams to report within ten days, were still investigating in November 2019, with no report as of June 2021. Hand tallies before and after 2019 had a perfect match with machine counts.

An experiment with multiple types of ballots counted by multiple teams found average errors of 0.5% in candidate tallies when one person, watched by another, read to two people tallying independently. Almost all these errors were overcounts. The same ballots had errors of 2.1% in candidate tallies from sort and stack. These errors were equally divided between undercounts and overcounts of the candidates. Optical scan ballots, which were tallied by both methods, averaged 1.87% errors, equally divided between undercounts and overcounts. Since it was an experiment, the true numbers were known. Participants thought that having the candidate names printed in larger type and bolder than the office and party would make hand tallies faster and more accurate.

Intentional errors hand tallying election results are fraud. Close review by observers, if allowed, may detect fraud, and the observers may or may not be believed. If only one person sees each ballot and reads off its choice, there is no check on that person's mistakes. In the US only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia give anyone but officials a legal right to see ballot marks during hand counting. If fraud is detected and proven, penalties may be light or delayed. US prosecution policy since the 1980s has been to let fraudulent winners take office and keep office, usually for years, until convicted, and to impose sentencing level 8-14, which earns less than two years of prison.

In 1934, the United States had been hand-counting ballots for over 150 years, and problems were described in a report by Joseph P. Harris, who 20 years later invented a punched card voting machine,

"Recounts in Chicago and Philadelphia have indicated such wide variations that apparently the precinct officers did not take the trouble to count the ballots at all... While many election boards pride themselves upon their ability to conduct the count rapidly and accurately, as a general rule the count is conducted poorly and slowly... precinct officers conduct the count with practically no supervision whatever... It is impossible to fix the responsibility for errors or frauds... Not infrequently there is a mixup with the ballots and some uncertainty as to which have been counted and which have not... The central count was used some years ago in San Francisco... experience indicated that there is considerable confusion at the central counting place... and that the results are not more accurate than those obtained from the count by the precinct officer."

| Place | Year | Candidate tally errors, as % of votes counted | Reference Standard | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire towns | 1946-1962 | 0.83% | careful hand recount | wtd avg is sum of absolute values of errors, divided by total ballots |

| New Hampshire towns | 2002 | 2.49% | careful hand recount | 20% in one town; others average 0.87% |

| Connecticut towns | 2007-2013 | up to 2% | investigations of differences between hand & machine counts | "routinely show up to 2% error" |

| Experiment, optical scan style ballots | 2011 | 1.87% | Known values in experiment | As % of all 120 ballots, not candidate's ballots |

| Experiment, read to talliers | 2011 | 0.48% | Known values in experiment | As % of all 120 ballots, not candidate's ballots |

| Experiment, sort & stack | 2011 | 2.13% | Known values in experiment | As % of all 120 ballots, not candidate's ballots |

| Wisconsin precincts | 2011 | 0.28% | careful hand recount | Table 6 "0.59% of the ballots" "out of 3,019" where 3,019 is total number of ballots |

| Wisconsin precincts | 2016 | 0.18% | careful hand recount | Table 7a. "0.59% of the ballots" but 0.18% if exclude write-ins |

| Indiana, Jeffersonville | 2016 | 3%-27% | Newspaper tally | Over-counted groups of 5 tally marks, and omitted or double-counted groups of ballots |

| Colorado audits | 2018 | 0.8% | Consensus between election computer & Sec of State staff | Errors by audit boards in determining voter intent on individual ballots. No manual totals done. |

| Colorado audits | 2019 | 0.2% | Consensus between election computer & Sec of State staff | Errors by audit boards in determining voter intent on individual ballots. No manual totals done. |

| India national election audit | 2019 | 8 of 20,625 machines audited | Discrepancy between hand tally of VVPATs & election computers | They investigated and have not released analysis, so it is not clear how many of these were errors in hand tally. |

| Colorado audits | 2020 | 0.6% | Consensus between election computer & Sec of State staff | Errors by audit boards in determining voter intent on individual ballots. No manual totals done. |

| Maricopa County, AZ audit | 2021 | 15% | Paper-counting machine | Audit & machine count were contracted by state Senate |

| Mohave County, AZ, experiment | 2023 | 0.15% | Logic & Accuracy Test ballots | 46 errors were 0.15% of 30,600 contest totals on 850 test ballots. |

Data in the table are comparable, because average error in candidate tallies as percent of candidate tallies, weighted by number of votes for each candidate (in NH) is mathematically the same as the sum of absolute values of errors in each candidate's tally, as percent of all ballots (in other studies).

Time needed and cost of manual counts

Cost depends on pay levels and staff time needed, recognizing that staff generally work in teams of two to four (one to read, one to watch, and one or two to record votes). Teams of four, with two to read and two to record are more secure and would increase costs. Three to record might more quickly resolve discrepancies, if 2 of the 3 agree.

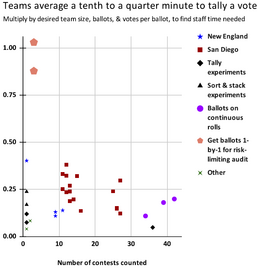

Typical times in the table below range from a tenth to a quarter of a minute per vote tallied, so 24-60 ballots per hour per team, if there are 10 votes per ballot.

One experiment with identical ballots of various types and multiple teams found that sorting ballots into stacks took longer and had more errors than two people reading to two talliers.

| Team (Wall Clock) Minutes per Vote Checked | Team Size | Staff Minutes per Vote Checked | Number of Contests Checked per Ballot | Full Precincts /Batches, or Random Ballots | Type of Paper Ballot | Number of Ballots Checked | Total Staff Time, Minutes | Year | Sources | Overheads Excluded & Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Searcy Cnty, AR | 8.47 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 1,700 | 14,400 | 2024 | Team size & total errors not given. Hand & machine counts of Early Vote for Wes Bradford matched at 517, but certified results showed 520 and tally sheets showed 518. Two other ballots in a precinct batch were omitted from hand and machine counts. Total of 11 were uncounted. | |||

| Butler Cnty, PA, Butler City | 0.02 | 6 | 0.09 | 8 | Full batches | Sheets | 600 | 450 | 2022 | 1 reads to 4-7. No report available, so times may be under-reported. Not on graph. | |

| Butler Cnty, PA, Donegal Twp | 0.02 | 4 | 0.08 | 8 | Full batches | Sheets | 1,061 | 660 | 2022 | 1 reads to 4-7. No report available, so times may be under-reported. Not on graph. | |

| Dane County, WI | 0.04 | 5 | 0.20 | 1 | Full sets of images | Sheets | 1000 | 200 | 2015 | Organizing ballot scans for review, training, legal, supervision | |

| Mohave County, AZ, experiment | 0.05 | 7 | 0.34 | 36 | Full batches | Sheets | 850 | 10,266 | 2023 | Excludes: detecting & retallying errors missed by team, space rental, paying workers to attend training, entering data on computer for web & SOS, creating blank tally sheets for each precinct. They estimate the following would add 33% to direct tallying cost: supervision, summation, sorting ballots by precinct, guards, transportation, background checks, webcams, recruitment | |

| Maricopa County, AZ recount | 0.08 | 5 | 0.42 | 2 | Full batches | Sheets | 1 | 0.83 | 2021 | Organizing ballots for review, training, legal, supervision, adding tally sheets | |

| New Hampshire | 0.09 | 3 | 0.27 | 20 | Full batches | Sheets | 627 | 3,360 | 2007 | Add 60% to cover: supervision 43% + training 13% + sums 4% | |

| Carlisle, MA | 0.11 | 2 | 0.22 | 9 | Full batches | Sheets | 3,670 | 7,200 | 2020 | 8 teams of 2 plus 4 extra | |

| Hancock, MA | 0.13 | 2 | 0.26 | 9 | Full batches | Sheets | 513 | 1,200 | 2020 | Organizing ballots for review, training, legal, supervision, adding tally sheets (10 teams of 2 | |

| Provincetown, MA | 0.14 | 2 | 0.28 | 11 | Full batches | Sheets | 2,616 | 7,980 | 2020 | 16 teams of 2+2 runners+4 tallies | |

| Tolland, CT | 0.11 | 7 | Full batches | Sheets | 3851 | 2,880 | 2012 | ||||

| Bloomfield, CT | 0.15 | 7 | Full batches | Sheets | 2272 | 2,400 | 2012 | ||||

| Vernon, CT | 0.31 | 6 | Full batches | Sheets | 2544 | 4,740 | 2012 | ||||

| Bridgeport, CT | 0.40 | 5 | 2.01 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 23860 | 48,000 | 2010 | Includes counting number of voters who checked in at polling places, and comparing those counts to ballot counts. | |

| Bibb County, GA | 0.18 | 3 | 0.54 | 39 | Full batches | Rolls | 592 | 12,480 | 2006 | ||

| Camden County, GA | 0.11 | 3 | 0.33 | 34 | Full batches | Rolls | 470 | 5,220 | 2006 | ||

| Cobb County, GA | 0.20 | 3 | 0.60 | 42 | Full batches | Rolls | 976 | 24,480 | 2006 | ||

| San Diego precincts | 0.22 | 3 | 0.67 | 19 | Full batches | Sheets | 2,425 | 30,573 | 2016 | ||

| Clark County, NV | 0.72 | 21 | Full batches | Rolls | 1,268 | 19,200 | 2004 | ||||

| Washington State recount | 1.49 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 1,842,136 | 2,741,460 | 2004 | ||||

| Orange County, CA | 1.93 | 1 | Full, mostly | Rolls mostly | 467 | 900 | 2011 | Independent count, done by graduate student on university computer | |||

| Read to Talliers Experiment Second Contest | 0.07 | 4 | 0.30 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 1800 | 537 | 2012 | Organizing ballots for review, training, legal, supervision, adding tally sheets | |

| Read to Talliers Experiment First Contest | 0.12 | 4 | 0.48 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 1800 | 861 | 2012 | Organizing ballots for review, training, legal, supervision, adding tally sheets | |

| Sort & Stack Experiment Second Contest | 0.17 | 3 | 0.51 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 1920 | 972 | 2012 | Organizing ballots for review, training, legal, supervision, adding tally sheets | |

| Sort & Stack Experiment First Contest | 0.24 | 3 | 0.71 | 1 | Full batches | Sheets | 1920 | 1,369 | 2012 | Organizing ballots for review, training, legal, supervision, adding tally sheets | |

| COUNTING BALLOTS IN RANDOM ORDER | |||||||||||

| Carroll County, MD | 1.03 | 2 | 2.06 | 3 | Random images | Sheets | 247 | 1,526 | 2016 | Organizing ballot scans for review, training, legal, supervision | |

| Montgomery County MD | 0.88 | 2 | 1.76 | 3 | Random images | Sheets | 82 | 432 | 2016 | Organizing ballot scans for review, training, legal, supervision | |

| Merced County, CA | 1.82 | 2 | Random ballots | Sheets | 198 | 720 | 2011 | Independent count, done by graduate student on university computer | |||

| Humboldt County, CA | 5.87 | 3 | Random ballots | Sheets | 143 | 2,520 | 2011 | Independent count, done by graduate student on university computer |

Mechanical counting

Mechanical voting machines have voters selecting switches (levers), pushing plastic chips through holes, or pushing mechanical buttons which increment a mechanical counter (sometimes called the odometer) for the appropriate candidate.

There is no record of individual votes to check.

Errors in mechanical counting

Tampering with the gears or initial settings can change counts, or gears can stick when a small object is caught in them, so they fail to count some votes. When not maintained well the counters can stick and stop counting additional votes; staff may or may not choose to fix the problem. Also, election staff can read the final results wrong off the back of the machine.

Electronic counting

Main articles: Electronic voting and Electronic voting machineElectronic machines for elections are being procured around the world, often with donor money. In places with honest independent election commissions, machines can add efficiency, though not usually transparency. Where the election commission is weaker, expensive machines can be fetishized, waste money on kickbacks and divert attention, time and resources from harmful practices, as well as reducing transparency.

An Estonian study compared the staff, computer, and other costs of different ways of voting to the numbers of voters, and found highest costs per vote were in lightly-used, heavily staffed early in-person voting. Lowest costs per vote were in internet voting and in-person voting on election day at local polling places, because of the large numbers of voters served by modest staffs. For internet voting they do not break down the costs. They show steps to decrypt internet votes and imply but do not say they are hand-counted.

Optical scan counting

Main article: Optical scan voting system Further information: Voting machine § Optical scan (marksense), Electronic voting § Paper-based electronic voting system, and Electronic voting in the United States § Optical scan counting

In an optical scan voting system, or marksense, each voter's choices are marked on one or more pieces of paper, which then go through a scanner. The scanner creates an electronic image of each ballot, interprets it, creates a tally for each candidate, and usually stores the image for later review.

The voter may mark the paper directly, usually in a specific location for each candidate, either by filling in an oval or by using a patterned stamp that can be easily detected by OCR software.

Or the voter may pick one pre-marked ballot among many, each with its own barcode or QR code corresponding to a candidate.

Or the voter may select choices on an electronic screen, which then prints the chosen names, usually with a bar code or QR code summarizing all choices, on a sheet of paper to put in the scanner. This screen and printer is called an electronic ballot marker (EBM) or ballot marking device (BMD), and voters with disabilities can communicate with it by headphones, large buttons, sip and puff, or paddles, if they cannot interact with the screen or paper directly. Typically the ballot marking device does not store or tally votes. The paper it prints is the official ballot, put into a scanning system which counts the barcodes, or the printed names can be hand-counted, as a check on the machines. Most voters do not look at the paper to ensure it reflects their choices, and when there is a mistake, an experiment found that 81% of registered voters do not report errors to poll workers.

Two companies, Hart and Clear Ballot, have scanners which count the printed names, which voters had a chance to check, rather than bar codes and QR codes, which voters are unable to check.

Timing of optical scans

The machines are faster than hand-counting, so are typically used the night after the election, to give quick results. The paper ballots and electronic memories still need to be stored, to check that the images are correct, and to be available for court challenges.

Errors in optical scans

Main article: Electronic voting in the United States § Errors in optical scansScanners have a row of photo-sensors which the paper passes by, and they record light and dark pixels from the ballot. A black streak results when a scratch or paper dust causes a sensor to record black continuously. A white streak can result when a sensor fails. In the right place, such lines can indicate a vote for every candidate or no votes for anyone. Some offices blow compressed air over the scanners after every 200 ballots to remove dust. Fold lines in the wrong places can also count as votes.

Software can miscount; if it miscounts drastically enough, people notice and check. Staff rarely can say who caused an error, so they do not know whether it was accidental or a hack. Errors from 2002-2008 were listed and analyzed by the Brennan Center in 2010. There have been numerous examples before and since.

- In a 2020 election in Baltimore, Maryland, the private company which printed ballots shifted the location of some candidates on some ballots up one line, so the scanner looked in the wrong places on the paper and reported the wrong numbers. It was caught because a popular incumbent got implausibly few votes.

- In a 2018 New York City election when the air was humid, ballots jammed in the scanner, or multiple ballots went through a scanner at once, hiding all but one.

- In a 2000 Bernalillo County (Albuquerque area), New Mexico, election, a programming error meant that straight-party votes on paper ballots were not counted for the individual candidates. The number of ballots was thus much larger than the number of votes in each contest. The software was fixed, and the ballots were re-scanned to get correct counts.

- In the 2000 Florida presidential race the most common optical scanning error was to treat as an overvote a ballot where the voter marked a candidate and wrote in the same candidate.

Researchers find security flaws in all election computers, which let voters, staff members or outsiders disrupt or change results, often without detection. Security reviews and audits are discussed in Electronic voting in the United States#Security reviews.

When a ballot marking device prints a bar code or QR code along with candidate names, the candidates are represented in the bar code or QR code as numbers, and the scanner counts those codes, not the names. If a bug or hack makes the numbering system in the ballot marking device not aligned with the numbering system in the scanner, votes will be tallied for the wrong candidates. This numbering mismatch has appeared with direct recording electronic machines (below).

Some US states check a small number of places by hand-counting or use of machines independent of the original election machines.

Recreated ballots

Recreated ballots are paper or electronic ballots created by election staff when originals cannot be counted for some reason. They usually apply to optical scan elections, not hand-counting. Reasons include tears, water damage and folds which prevent feeding through scanners. Reasons also include voters selecting candidates by circling them or other marks, when machines are only programmed to tally specific marks in front of the candidate's name. As many as 8% of ballots in an election may be recreated.

Recreating ballots is sometimes called reconstructing ballots, ballot replication, ballot remaking or ballot transcription. The term "duplicate ballot" sometimes refers to these recreated ballots, and sometimes to extra ballots erroneously given to or received from a voter.

Recreating can be done manually, or by scanners with manual review.

Because of its potential for fraud, recreation of ballots is usually done by teams of two people working together or closely observed by bipartisan teams. The security of a team process can be undermined by having one person read to the other, so only one looks at the original votes and one looks at the recreated votes, or by having the team members appointed by a single official.

When auditing an election, audits need to be done with the original ballots, not the recreated ones.

Cost of scanning systems

List prices of optical scanners in the US in 2002-2019, ranged from $5,000 to $111,000 per machine, depending primarily on speed. List prices add up to $1 to $4 initial cost per registered voter. Discounts vary, based on negotiations for each buyer, not on number of machines purchased. Annual fees often cost 5% or more per year, and sometimes over 10%. Fees for training and managing the equipment during elections are additional. Some jurisdictions lease the machines so their budgets can stay relatively constant from year to year. Researchers say that the steady flow of income from past sales, combined with barriers to entry, reduces the incentive for vendors to improve voting technology.

If most voters mark their own paper ballots and one marking device is available at each polling place for voters with disabilities, Georgia's total cost of machines and maintenance for 10 years, starting 2020, has been estimated at $12 per voter ($84 million total). Pre-printed ballots for voters to mark would cost $4 to $20 per voter ($113 million to $224 million total machines, maintenance and printing). The low estimate includes $0.40 to print each ballot, and more than enough ballots for historic turnout levels. the high estimate includes $0.55 to print each ballot, and enough ballots for every registered voter, including three ballots (of different parties) for each registered voter in primary elections with historically low turnout. The estimate is $29 per voter ($203 million total) if all voters use ballot marking devices, including $0.10 per ballot for paper.

The capital cost of machines in 2019 in Pennsylvania is $11 per voter if most voters mark their own paper ballots and a marking device is available at each polling place for voters with disabilities, compared to $23 per voter if all voters use ballot marking devices. This cost does not include printing ballots.

New York has an undated comparison of capital costs and a system where all voters use ballot marking devices costing over twice as much as a system where most do not. The authors say extra machine maintenance would exacerbate that difference, and printing cost would be comparable in both approaches. Their assumption of equal printing costs differs from the Georgia estimates of $0.40 or $0.50 to print a ballot in advance, and $0.10 to print it in a ballot marking device.

Direct-recording electronic counting

Main article: DRE voting machine Further information: Voting machine § Direct-recording electronic (DRE), Electronic voting § Direct-recording electronic (DRE) voting system, and Electronic voting in the United States § Direct-recording electronic counting

A touch screen displays choices to the voter, who selects choices, and can change their mind as often as needed, before casting the vote. Staff initialize each voter once on the machine, to avoid repeat voting. Voting data and ballot images are recorded in memory components, and can be copied out at the end of the election.

The system may also provide a means for communicating with a central location for reporting results and receiving updates, which is an access point for hacks and bugs to arrive.

Some of these machines also print names of chosen candidates on paper for the voter to verify. These names on paper can be used for election audits and recounts if needed. The tally of the voting data is stored in a removable memory component and in bar codes on the paper tape. The paper tape is called a Voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT). The VVPATs can be counted at 20–43 seconds of staff time per vote (not per ballot).

For machines without VVPAT, there is no record of individual votes to check.

Errors in direct-recording electronic voting

This approach can have software errors. It does not include scanners, so there are no scanner errors. When there is no paper record, it is hard to notice or research most errors.

- The only forensic examination which has been done of direct-recording software files was in Georgia in 2020, and found that one or more unauthorized intruders had entered the files and erased records of what it did to them. In 2014-2017 an intruder had control of the state computer in Georgia which programmed vote-counting machines for all counties. The same computer also held voter registration records. The intrusion exposed all election files in Georgia since then to compromise and malware. Public disclosure came in 2020 from a court case. Georgia did not have paper ballots to measure the amount of error in electronic tallies. The FBI studied that computer in 2017, and did not report the intrusion.

- A 2018 study of direct-recording voting machines (iVotronic) without VVPAT in South Carolina found that every election from 2010-2018 had some memory cards fail. The investigator also found that lists of candidates were different in the central and precinct machines, so 420 votes which were properly cast in the precinct were erroneously added to a different contest in the central official tally, and unknown numbers were added to other contests in the central official tallies. The investigator found the same had happened in 2010. There were also votes lost by garbled transmissions, which the state election commission saw but did not report as an issue. 49 machines reported that their three internal memory counts disagreed, an average of 240 errors per machine, but the machines stayed in use, and the state evaluation did not report the issue, and there were other error codes and time stamp errors.

- In a 2017 York County, Pennsylvania, election, a programming error in a county's machines without VVPAT let voters vote more than once for the same candidate. Some candidates had filed as both Democrat and Republican, so they were listed twice in races where voters could select up to three candidates, so voters could select both instances of the same name. They recounted the DRE machines' electronic records of votes and found 2,904 pairs of double votes.

- In a 2011 Fairfield Township, New Jersey, election a programming error in a machine without a VVPAT gave two candidates low counts. They collected more affidavits by voters who voted for them than the computer tally gave them, so a judge ordered a new election which they won.

- A 2007 study for the Ohio Secretary of State reported on election software from ES&S, Premier and Hart. Besides the problems it found, it noted that all "election systems rely heavily on third party software that implement interfaces to the operating systems, local databases, and devices such as optical scanners... the construction and features of this software is unknown, and may contain undisclosed vulnerabilities such trojan horses or other malware."

General issues

Interpretation, in any counting method

Election officials or optical scanners decide if a ballot is valid before tallying it. Reasons why it might not be valid include: more choices selected than allowed; incorrect voter signature or details on ballots received by mail, if allowed; lack of poll worker signatures, if required; forged ballot (wrong paper, printing or security features); stray marks which could identify who cast the ballot (to earn payments); and blank ballots, though these may be counted separately as abstentions.

For paper ballots officials decide if the voter's intent is clear, since voters may mark lightly, or circle their choice, instead of marking as instructed. The ballot may be visible to observers to ensure agreement, by webcam or passing around a table, or the process may be private. In the US only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia give anyone but officials a legal right to see ballot marks during hand counting. For optical scans, the software has rules to interpret voter intent, based on the darkness of marks. Software may ignore circles around a candidate name, and paper dust or broken sensors can cause marks to appear or disappear, not where the voter intended.

Officials also check if the number of voters checked in at the polling place matches the number of ballots voted, and that the votes plus remaining unused ballots matches the number of ballots sent to the polling place. If not, they look for the extra ballots, and may report discrepancies.

Secure storage to enable counts in future

If ballots or other paper or electronic records of an election may be needed for counting or court review after a period of time, they need to be stored securely.

Election storage often uses tamper-evident seals, although seals can typically be removed and reapplied without damage, especially in the first 48 hours. Photos taken when the seal is applied can be compared to photos taken when the seal is opened. Detecting subtle tampering requires substantial training. Election officials usually take too little time to examine seals, and observers are too far away to check seal numbers, though they could compare old and new photos projected on a screen. If seal numbers and photos are kept for later comparison, these numbers and photos need their own secure storage. Seals can also be forged. Seals and locks can be cut so observers cannot trust the storage. If the storage is breached, election results cannot be checked and corrected.

Experienced testers can usually bypass all physical security systems. Locks and cameras are vulnerable before and after delivery. Guards can be bribed or blackmailed. Insider threats and the difficulty of following all security procedures are usually under-appreciated, and most organizations do not want to learn their vulnerabilities.

Security recommendations include preventing access by anyone alone, which would typically require two hard-to-pick locks, and having keys held by independent officials if such officials exist in the jurisdiction; having storage risks identified by people other than those who design or manage the system; and using background checks on staff.

No US state has adequate laws on physical security of the ballots.

Starting the tally soon after voting ends makes it feasible for independent parties to guard storage sites.

Secure transport and internet

The ballots can be carried securely to a central station for central tallying, or they can be tallied at each polling place, manually or by machine, and the results sent securely to the central elections office. Transport is often accompanied by representatives of different parties to ensure honest delivery. Colorado transmits voting records by internet from counties to the Secretary of State, with hash values also sent by internet to try to identify accurate transmissions.

Postal voting is common worldwide, though France stopped it in the 1970s because of concerns about ballot security. Voters who receive a ballot at home may also hand-deliver it or have someone else to deliver it. The voter may be forced or paid to vote a certain way, or ballots may be changed or lost during the delivery process, or delayed so they arrive too late to be counted or for signature mis-matches to be resolved.

Postal voting lowered turnout in California by 3%. It raised turnout in Oregon only in Presidential election years by 4%, turning occasional voters into regular voters, without bringing in new voters. Election offices do not mail to people who have not voted recently, and letter carriers do not deliver to recent movers they do not know, omitting mobile populations.

Some jurisdictions let ballots be sent to the election office by email, fax, internet or app. Email and fax are highly insecure. Internet so far has also been insecure, including in Switzerland, Australia, and Estonia. Apps try to verify the correct voter is using the app by name, date of birth and signature, which are widely available for most voters, so can be faked; or by name, ID and video selfie, which can be faked by loading a pre-recorded video. Apps have been particularly criticized for operating on insecure phones, and pretending to more security during transmission than they have.

See also

- Recount

- Tally (voting)

- Electronic voting

- Electronic voting in Switzerland

- Voting machine

- Electoral system

- Ballot

- Election audits

- Elections

- Electoral fraud

- Electoral integrity

- List of close election results

References

- "Chapter 13: Canvassing and Certifying an Election". Election Management Guidelines (PDF). U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

- Reinhard, Beth; Wingett Sanchez, Yvonne (September 26, 2022). "As more states create election integrity units, Arizona is a cautionary tale". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ History of Voting Technology Archived 2013-11-01 at the Wayback Machine from PBS's The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer

- ^ "Post-Election Tabulation Audit Pilot Program Report" (PDF). Maryland State Board of Elections. October 2016. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- "2018 Post-Election Review Guide" (PDF). Minnesota Secretary of State. 2018-07-19.

- ^ "Country Examples Index —". ACE-Electoral Knowledge Network. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ "FOR ELECTION OFFICIALS". Wisconsin Election Integrity. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ McKim, Karen (January 2016). "Using automatically created digital ballot images to verify voting-machine output in Wisconsin" (PDF). Wisconsin Election Integrity. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- Fifield, Jen and Andrew Oxford (2021-04-24). "Arizona election audit: Here's what you're seeing on the video feeds as counting continues Saturday". Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- "Ballot Image Audit Guide for Candidates and Campaigns" (PDF). AuditElectionsUSA.org/download-guide. 2018-11-26. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Lutz, Ray (2017-01-10). "The Open Ballot Initiative" (PDF). OpenBallotInitiative.org. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Trachtenberg, Mitch (2013-06-29). "The Humboldt County Election Transparency Project and TEVS" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- "States/Counties that Use Ballot Images from Paper Ballots". AUDIT USA. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- "I. Election Records Archives". The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- "Reporters Committee Election Legal Guide, Updated 2020". The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- "National Association of Secretaries of State Survey". 2013-02-17. Archived from the original on 2013-02-17. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- "NORC Florida Ballots Project". 2001-12-14. Archived from the original on 2001-12-14. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Game, Chris (May 7, 2015). "Explainer: how Britain counts its votes". The Conversation. Retrieved August 16, 2019. Keaveney, Paula (June 8, 2017). "How votes are counted on election night". The Conversation. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "Elections, Our Country, Our Parliament". lop.parl.ca. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "Qu'est-ce qu'un dépouillement ? - Comment se déroule une journée dans un bureau de vote ? Découverte des institutions - Repères - vie-publique.fr" (in French). January 14, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "Stimmenauszählung". Mülheim an der Ruhr (in German). 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- "¿Qué es el escrutinio y cómo se cuentan los votos en las elecciones generales 2019?". El Confidencial (in Spanish). April 28, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019. and Section 14 of the law:"Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de Junio, del régimen electoral general. SECCIÓN 14.ª ESCRUTINIO EN LAS MESAS ELECTORALES". www.juntaelectoralcentral.es. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- "Starting to audit only when all the audit units have already been counted is the most straightforward method." "Principles and Best Practices for Post-Election Tabulation Audits" (PDF). ElectionAudits.org. 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Australian Electoral Commission. "House of Representatives count". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- Australian Electoral Commission. "The Senate counting process". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- Explaining Election Day: How hand counting votes carries risks. Retrieved 2024-10-10 – via apnews.com.

- ^ "Ballot Hand Tally" (PDF). Mohave County Board of Supervisors. 2023-07-25. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ^ BEILMAN, ELIZABETH. "Jeffersonville City Council At-large recount tally sheets show vote differences". News and Tribune (Jeffersonville, IN). Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- Contreras, Natalia (2024-03-18). "Texas county's GOP officials declared hand count a success, but kept finding errors". Votebeat. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Ansolabehere, Stephen; Andrew Reeves (January 2004). "Using Recounts to Measure the Accuracy of Vote Tabulations: Evidence from New Hampshire Elections 1946-2002" (PDF). CALTECH/MIT Voting Technology Project. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ Antonyan, Tigran; et al. (2013-06-21). "Computer Assisted Post Election Audits" (PDF). State Certification Testing of Voting Systems National Conference – via University of Connecticut.

- ^ Ansolabehere, Stephen; Burden, Barry C.; Mayer, Kenneth R.; Stewart, Charles (2018-03-20). "Learning from Recounts". Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy. 17 (2): 100–116. doi:10.1089/elj.2017.0440. ISSN 1533-1296.

- ^ Mahapatra, Dhananjay (2019-04-09). "Supreme Court: Count VVPAT slips of 5 booths in each assembly seat". Times of India. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Jain, Bharti (2021-06-03). "Tallying of VVPAT slips and EVM count in constituencies that went to polls recently throw up 100% match". Times of India. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- "What are EVMs, VVPAT and how safe they are". Times of India. 2019-03-09. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- Nath, Damini (2019-07-25). "ECI sets up teams to probe VVPAT mismatch in Lok Sabha election". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Goggin, Stephen N.; et al. (March 2012). "Post-Election Auditing: Effects of Procedure and Ballot Type on Manual Counting Accuracy, Efficiency, and Auditor Satisfaction and Confidence". Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy. 11 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1089/elj.2010.0098. ISSN 1533-1296.

- ^ Pickles, Eric (2016-12-27). "Securing the ballot: review into electoral fraud". Cabinet Office, UK. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ "State Audit Laws". Verified Voting. 2017-02-10. Archived from the original on 2020-01-04. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- "Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses Eighth Edition". US Department of Justice. December 2017. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- "Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses". votewell.net. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- "2018 Chapter 2 PART C - OFFENSES INVOLVING PUBLIC OFFICIALS AND VIOLATIONS OF FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGN LAWS". United States Sentencing Commission. 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- "Sentencing Table" (PDF). US Sentencing Commission. 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- Harris, Joseph P.; Nathan, Harriet, eds. (1983). "Joseph P. Harris: Professor and Practitioner: Government, Election Reform, and the Votomatic". UC Berkeley. Regional Oral History Office. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- Harris, Joseph P. (1934). "Election Administration in the United States, chapter VI, pages 236-246". NIST, originally published by Brookings. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ "Colorado Risk Limiting Audits: Three Years In" (PDF). Colorado Sec. of State. 2020-04-16. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- "2020 General Election Risk-limiting Audit Discrepancy Report" (PDF). Colorado Sec of State. 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- Anglen, Robert (2021-10-12). "New Arizona audit review shows Cyber Ninjas' ballot count off by 312K". Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2022-07-29. Full article

- "Scan of Pullen Pallets Binders 1-45". Statecraftlaw. 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ pp.21-22,44 Tobi, Nancy (2007-09-06). "Hands-on Elections: (Condensed Version)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- "Post-Election Audit Report 2024 General Election [actually preference primary], pages 4,5,24,25" (PDF). Arkansas State Board of Election Commissioners. 2024-08-23. Retrieved 2024-10-05.

- Madison, Richard Chris (2024-06-27). "Re: March 2024 Preferential Primary Audit Process" (PDF). Arkansas Advocate. Retrieved 2024-10-05.

- ^ McGoldrick, Gillian (2022-08-17). "Butler County finishes its review of 2020 election, finds no inaccuracies among 1,600 ballot". Pittsburgh Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2022-08-29. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ^ McGoldrick, Gillian (2022-08-18). "Butler County Finishes 2020 Election Review After 170 Hours". Governing. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- Note this line includes 7-person teams to tally: 1 reader+2 watchers, 2 talliers+2 watchers; plus 3 people to enter write-ins @30 seconds per write-in, 15% write-ins. https://resources.mohave.gov/Repository/Calendar/08_01_2023BOSAgenda0fe47379-660b-465f-a8b5-4eb9fc976f30.pdf p.4 says 46 errors were missed by tally team, and only known because the 850 test ballots had been repeatedly counted in Logic & Accuracy Tests. "Some of the observed errors included:

- Caller called the wrong candidate and both watchers failed to notice the incorrect call;

- Tally markers tried to work out inconsistencies while tallying;

- Tally markers marked a vote for an incorrect candidate and the watchers failed to notice the error;

- Caller calling too fast resulted in double marking a candidate or missed marking a candidate;

- Caller missed calling a vote for a candidate and both watchers failed to notice the omission;

- Watchers not watching the process due to boredom or fatigue;

- Illegible tally marking caused incorrect tally totaling;

- Enunciation of names caused incorrect candidate tally; and

- Using incorrect precinct tally sheets to tally ballots resulted in incorrect precinct level results

- Polletta, Maria and Piper Hansen (2021-04-28). "Here's what happened at the Arizona election audit of Maricopa County ballots". Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2021-05-06.

- Tobi, Nancy (2011). Hands-on elections : an informational handbook for running real elections, using real paper ballots, counted by real people : lessons from New Hampshire (2nd ed.). Wilton, N.H.: Healing Mountain Publications. ISBN 978-1-4528-0612-9. OCLC 816513645.

- Connecticut Citizen Election Audit Coalition (2011-01-12). "Report and Feedback December 2010 Bridgeport Connecticut Coalition Recount". Archived from the original on 2012-04-19.

- ^ Georgia Secretary of State, Elections Division. (2007-04). " (April 1, 2007). "Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail Pilot Project Report. Pages 18-22, 42-63" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Lutz, Ray (2019-01-28). "White Paper: Election Audit Strategy" (PDF). Citizens' Oversight Projects. Retrieved 2021-04-13.

- ^ Theisen, Ellen (2004). "Cost Estimate for Hand Counting 2% of the Precincts in the U.S." (PDF). votersunite.org. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ Bowen, Debra (2011-03-01). "AB 2023 (Saldaña), Chapter 122, Statutes of 2010 Post-Election Risk-Limiting Audit Pilot Program March 1, 2012, Report to the Legislature" (PDF). California Secretary of State. Retrieved 2021-05-30. and California Secretary of State (July 30, 2014). "Post-Election Risk-Limiting Audit Pilot Program 2011-2013, Final Report to the United States Election Assistance Commission" (PDF). Internet Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-02. AND California Secretary of State (July 30, 2014). "Appendices, Post-Election Risk-Limiting Audit Pilot Program 2011-2013 Final Report to the United States Election Assistance Commission." Pages 81-90" (PDF). Internet Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-02. AND Overview. The time estimates of other California counties in the study included time to scan ballots to enable ballot comparison audits, so their costs were not comparable. None of the 11 California counties doing audits chose a close race or needed a 100% hand-count.

- ^ Maryland State Board of Elections (October 21, 2016). "Post-Election Tabulation Audit Pilot Program Report" (PDF). elections.maryland.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Shapiro, Eliza (2012-11-10). "RIP, Lever Voting Machines". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "Vote: The Machinery of Democracy". Smithsonian Institution. 16 March 2012. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Emspak, Jesse (2016-11-08). "Why Not Paper Ballots? America's Weird History of Voting Machines". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- McKim, Karen (2014-05-15). "It happens all the time: Interview with the consultant who discovered the Medford miscount". Wisconsin Grassroots Network. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- Cheeseman, Nic; Lynch, Gabrielle; Willis, Justin (2018-11-17). "Digital dilemmas: the unintended consequences of election technology". Democratization. 25 (8): 1397–1418. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1470165. S2CID 150032446.

- Krimmer, Robert; Duenas-Cid, David; Krivonosova, Iuliia (2021-01-02). "New methodology for calculating cost-efficiency of different ways of voting: is internet voting cheaper?". Public Money & Management. 41: 17–26. doi:10.1080/09540962.2020.1732027. S2CID 212822266.

- "Ballot Marking Devices". Verified Voting. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Cohn, Jennifer (2018-05-05). "What is the latest threat to democracy?". Medium. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Bernhard, Matthew; Allison McDonald; Henry Meng; Jensen Hwa; Nakul Bajaj; Kevin Chang; J. Alex Halderman (2019-12-28). "Can Voters Detect Malicious Manipulation of Ballot Marking Devices?" (PDF). Halderman. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Perez, Edward; Joy London; Gregory Miller (March 2019). "Georgia State Election Technology Acquisition, Assessing Recent Legislation in Light of Planned Procurement" (PDF). OSET Institute. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- Walker, Natasha (2017-02-13). "2016 Post-Election Audits in Maryland" (PDF). Elections Advisory Commission. Retrieved 2020-02-27.

- Ryan, Tom and Benny White (November 30, 2016). "Transcript of Email on Ballot Images" (PDF). Pima County, AZ. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Gideon, John (July 5, 2005). "Hart InterCivic Optical-Scan Has A Weak Spot". www.votersunite.org. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- McKim, Karen (2015-02-17). "Unregistered Dust Bunnies May be Voting in Wisconsin Elections: Stoughton Miscount Update". Wisconsin Grassroots Network. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- Appel, Andrew (2021-06-07). "New Hampshire Election Audit, part 2". Princeton University. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- Norden, Lawrence (September 16, 2010). "Voting system failures: a database solution" (PDF). Brennan Center, NYU. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Opilo, Emily; Talia Richman; Phil Davis (June 3, 2020). "Concern from candidates, officials as error creates delay in release of returns; Dixon leads in Baltimore mayoral count". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- MacDougall, Ian (November 7, 2018). "What Went Wrong at New York City Polling Places? It Was Something in the Air. Literally". ProPublica. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- Gruley, Bryan; Chip Cummins (2000-12-16). "Election Day Became a Nightmare, As Usual, for Bernalillo County". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- Baker, Deborah (2004-10-31). "ABQjournal: Contentious 2000 Election Closest in N.M. History". Albuquerque Journal. Archived from the original on 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- Blaze, Matt; Harri Hursti; Margaret Macalpine; Mary Hanley; Jeff Moss; Rachel Wehr; Kendal L Spencer; Christopher Ferris (2019-09-26). "DEF CON 27 Voting Machine Hacking Village" (PDF). Defcon. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- ^ Buell, Duncan (December 23, 2018). Analysis of the Election Data from the 6 November 2018 General Election in South Carolina (PDF). League of Women Voters of South Carolina (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "observers from both political parties there... ballots have to be recreated in every election for a number of reasons, ranging from damaged mail-in ballots, to early voters who use pencils which can’t be read by ballot tabulators." Jordan, Ben (2018-11-07). "MKE Election Commission responds to criticism". WTMJ TV Milwaukee. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ "With the new digital procedure, staff will be able to fix whatever race couldn’t be counted, instead of duplicating a voter’s entire ballot." White, Rebecca (2019-11-18). "One Washington County Plans to Speed Vote Counting with Tech". Government Technology. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Miller, Steve (2006-11-07). "Oddly marked ovals bane of poll workers' day". Rapid City Journal. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Shafer, Michelle (2020-07-20). "Ballot Duplication: What it is, what it is not, and why we are talking about it". Council of State Governments. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- Black, Eric (2008-12-17). "Recount's next big issue: duplicate ballots". MinnPost. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Tomasic, Megan (2020-05-14). "Some Allegheny County voters received duplicate mail-in ballots due to system glitch". Tribune Review. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Shafer, Michelle (2020-08-31). "Ballot Duplication Technology: What is it and how does it work?". Council of State Governments. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- Duplicate ballot procedures in Ventura County, CA https://recorder.countyofventura.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/BALLOT-DUPLICATION-PROCESS-FACTS-2-Final-1.pdf

- Duplicate ballot procedures in Michigan https://www.michigan.gov/documents/sos/XII_Precinct_Canvass_-_Closing_the_Polls_266013_7.pdf

- Caulfield, Matthew; Andrew Coopersmith; Arnav Jagasia; Olivia Podos (2021-03-30). "Price of Voting" (PDF). Verified Voting.

- ^ Perez, Edward; Gregory Miller (March 2019). "Georgia State Election Technology Acquisition, A Reality Check". OSET Institute. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- Fowler, Stephen. "Here's What Vendors Say It Would Cost To Replace Georgia's Voting System". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Deluzio, Christopher; Kevin Skoglund (2020-02-28). "Pennsylvania Counties' New Voting Systems Selections: An Analysis" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-06-26. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- "NYVV - Paper Ballots Costs". www.nyvv.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- 2005 Voluntary Voting System Guidelines Archived 2006-02-08 at the Wayback Machine from the US Election Assistance Commission

- Theisen, Ellen (2005-06-14). "Cost Estimate for Hand Counting 2% of the Precincts in the U.S." (PDF). VotersUnite.org. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ Lamb, Logan (2020-01-14). "SUPPLEMENTAL DECLARATION OF LOGAN LAMB" (PDF). CourtListener. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- "Coalition Plaintiffs' Status Report, pages 237-244". Coalition for Good Governance. 2020-01-16. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- Bajak, Frank (2020-01-16). "Expert: Georgia election server showed signs of tampering". Associated Press. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- Zetter, Kim. "Will the Georgia Special Election Get Hacked?". Politico. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Freed, Benjamin (2019-01-07). "South Carolina voting machines miscounted hundreds of ballots, report finds". Scoop News Group. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- Kessler, Brandie; Boeckel, Teresa; Segelbaum, Dylan (2017-11-07). "'Redo' of some York County races - including judge - possible after voting problems". York Daily Record. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- Lee, Rick (2017-11-20). "UPDATE: York Co. election judicial winners: Kathleen Prendergast, Clyde Vedder, Amber Anstine Kraft". York Daily Record. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- Thibodeau, Patrick (2016-10-05). "If the election is hacked, we may never know". ComputerWorld. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- McDaniel; et al. (2007-12-07). EVEREST: Evaluation and Validation of Election-Related Equipment, Standards and Testing (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ^ "Chapter 3. PHYSICAL SECURITY" (PDF). US Election Assistance Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- Lindeman, Mark; Bretschneider, Jennie; Flaherty, Sean; Goodman, Susannah; Halvorson, Mark; Johnston, Roger; Rivest, Ronald L.; Smith, Pam; Stark, Philip B. (October 1, 2012). "Risk-Limiting Post-Election Audits: Why and How" (PDF). University of California at Berkeley. pp. 3, 16. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ Johnston, Roger G.; Jon S. Warner (July 31, 2012). "How to Choose and Use Seals". Army Sustainment. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- Stark, Philip (July 26, 2018). "An Introduction to Risk-Limiting Audits and Evidence-Based Elections Prepared for the Little Hoover Commission" (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- Coherent Cyber (August 28, 2017). "Security Test Report ES&S Electionware 5.2.1.0" (PDF). Freeman, Craft McGregor Group. p. 9 – via California Secretary of State.

- Stauffer, Jacob (November 4, 2016). "Vulnerability & Security Assessment Report Election Systems &Software's Unity 3.4.1.0" (PDF) – via Freeman, Craft, MacGregor Group for California Secretary of State.

- ^ Seivold, Garett (April 2, 2018). "Physical Security Threats and Vulnerabilities - LPM". losspreventionmedia.com. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- There are several sources on lock vulnerabilities:

- Lockpicking is widely taught and practiced: Vanderbilt, Tom (March 12, 2013). "The Strange Things That Happen at a Lock-picking Convention". Slate. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Different techniques apply to electronic locks: Menn, Joseph (August 6, 2019). "Exclusive: High-security locks for government and banks hacked by researcher". Reuters. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- More on electronic locks: Greenberg, Andy (August 29, 2017). "Inside an Epic Hotel Room Hacking Spree". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- There are no statistics on how often criminals enter rooms undetected, but law enforcement often does so, so ability to enter rooms undetected is widespread: Tien, Lee (October 26, 2014). "Peekaboo, I See You: Government Authority Intended for Terrorism is Used for Other Purposes". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Security camera flaws have been covered extensively:

- Bannister, Adam (October 7, 2016). "How to hack a security camera. It's alarmingly simple". IFSEC Global, Security and Fire News and Resources. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- Doffman, Zak. "Official Cybersecurity Review Finds U.S. Military Buying High-Risk Chinese Tech (Updated)". Forbes. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- Schneier, Bruce (October 8, 2007). "Hacking Security Cameras - Schneier on Security". www.schneier.com. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- Dunn, John (June 11, 2019). "Critical flaws found in Amcrest security cameras". Naked Security. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- Turner, Karl (November 5, 2007). "Elections board workers take plea deal". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- Recount Now (January 11, 2017). "Report on the 2016 Presidential Recount in Clark County, Nevada. Page 20" (PDF). Internet Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-12. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- "Principles and Best Practices for Post-Election Tabulation Audits" (PDF). ElectionAudits.org. 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Benaloh; et al. (2017). "Public Evidence from Secret Ballots". Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Electronic Voting. Cham, Switzerland. p. 122. arXiv:1707.08619. ISBN 9783319686875. OCLC 1006721597.

- Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) policy calls for independent foreign officials to sleep with ballots, and allows parties to do so:

- International Crisis Group (ICG) (September 10, 1997). "Municipal Elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina". RefWorld. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- "OHR SRT News Summary, September 7, 1998". Office of the High Representative (Bosnia+Herzegovina). September 7, 1998. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- "Turkey's opposition sleeping beside ballots to safeguard democracy". Ahval. April 4, 2019. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Gall, Carlotta (April 1, 2019). "A Political Quake in Turkey as Erdogan's Party Loses in His Home Base of Support". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Cobb, Sue (2016-10-17). "The 2000 Presidential Election – The Florida Recount". Association for Diplomatic Studies & Training. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- Baker, Deborah (2004-10-31). "ABQjournal: Contentious 2000 Election Closest in N.M. History". Albuquerque Journal. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Rule 25. Post-election audit" (PDF). Colorado Secretary of State. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- "Judge upholds vote-rigging claims". BBC. 2005-04-04. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Mawrey, Richard (2010-11-01). "Judgment of Commissioner Mawrey QC Handed down on Monday 4th April 2005 in the matters of Local Government elections for the Bordesley Green and Aston Wards of the Birmingham City Council both held on 10th June 2004". Archived from the original on 2010-11-01. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- "Thousands of mailed ballots in Florida were not counted". NBC News. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- "If you vote by mail in Florida, it's 10 times more likely that ballot won't count". miamiherald. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- Kousser, Thad; Megan Mullin (2007-07-13). "Does Voting by Mail Increase Participation? Using Matching to Analyze a Natural Experiment" (PDF). Political Analysis. 15 (4): 428–445. doi:10.1093/PAN/MPM014. S2CID 33267753. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- BERINSKY, ADAM J.; NANCY BURNS; MICHAEL W. TRAUGOTT (2001). "Who Votes by Mail?: A Dynamic Model of the Individual-Level Consequences of Voting-by-Mail Systems" (PDF). Public Opinion Quarterly. 65 (2): 178–197. doi:10.1086/322196. PMID 11420755. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Slater, Michael; Teresa James (2007-06-29). "Vote-by-Mail Doesn't Deliver". NonprofitVote.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- "Electronic Transmission of Ballots". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Jefferson, David. "What About Email and Fax?". Verified Voting. Archived from the original on 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Zetter, Kim (2019-02-21). "Experts Find Serious Problems With Switzerland's Online Voting System". Vice. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Porup, J. M. (2018-05-02). "Online voting is impossible to secure. So why are some governments using it?". CSO. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- "Independent Report on E-voting in Estonia - A security analysis of Estonia's Internet voting system by international e-voting experts". Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Parks, Miles (2020-01-22). "Exclusive: Seattle-Area Voters To Vote By Smartphone In 1st For U.S. Elections". NPR. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ Jefferson, David (2019-05-01). "What We Don't Know About the Voatz "Blockchain" Internet Voting System" (PDF). University of South Carolina. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Zetter, Kim (2020-02-13). "'Sloppy' Mobile Voting App Used in Four States Has 'Elementary' Security Flaws". Vice. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Specter, Michael A.; James Koppel; Daniel Weitzner (2020-02-12). "The Ballot is Busted Before the Blockchain: A Security Analysis of Voatz, the First Internet Voting Application Used in U.S. Federal Elections" (PDF). MIT. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

External links

- The Election Technology Library research list – a comprehensive list of research relating to technology use in elections

- E-Voting information from ACE Project

- AEI-Brookings Election Reform Project

- Voting and Elections by Douglas W. Jones: Thorough articles about the history and problems with Voting Machinery

- Selker, Ted Scientific American Magazine Fixing the Vote October 2004

- The Machinery of Democracy: Voting System Security, Accessibility, Usability, and Cost from Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law

- An index of articles on vote counting from the ACE Project guide to designing and administering elections