| This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. Please help by spinning off or relocating any relevant information, and removing excessive detail that may be against Misplaced Pages's inclusion policy. (April 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| ISO 4217 | |

|---|---|

| Code | XAU (numeric: 959) |

| Unit | |

| Symbol | XAU |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) | Investors |

Of all the precious metals, gold is the most popular as an investment. Investors generally buy gold as a way of diversifying risk, especially through the use of futures contracts and derivatives. The gold market is subject to speculation and volatility as are other markets. Compared to other precious metals used for investment, gold has been the most effective safe haven across a number of countries.

Gold price

Gold has been used throughout history as money and has been a relative standard for currency equivalents specific to economic regions or countries, until recent times. Many European countries implemented gold standards in the latter part of the 19th century until these were temporarily suspended in the financial crises involving World War I. After World War II, the Bretton Woods system pegged the United States dollar to gold at a rate of US$35 per troy ounce. The system existed until the 1971 Nixon shock, when the US unilaterally suspended the direct convertibility of the United States dollar to gold and made the transition to a fiat currency system. The last major currency to be divorced from gold was the Swiss franc in 2000.

Since 1919 the most common benchmark for the price of gold has been the London gold fixing, a twice-daily telephone meeting of representatives from five bullion-trading firms of the London bullion market. Furthermore, gold is traded continuously throughout the world based on the intra-day spot price, derived from over-the-counter gold-trading markets around the world (code "XAU"). The following table sets out the gold price versus various assets and key statistics at five-year intervals.

| Year | Gold USD/ ozt |

DJIA | World GDP | US Debt | Debt per capita | Trade-weighted US dollar index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD | XAU | USD (trillions) | XAU (billions) | USD (billions) | XAU (billions) | USD | XAU | |||

| 1970 | 37 | 839 | 22.7 | 3.3 | 89.2 | 370 | 10.0 | 1,874 | 50.6 | |

| 1975 | 140 | 852 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 45.7 | 533 | 3.8 | 2,525 | 18.0 | 33.0 |

| 1980 | 590 | 964 | 1.6 | 11.8 | 20.0 | 908 | 1.5 | 4,013 | 6.8 | 35.7 |

| 1985 | 327 | 1,547 | 4.7 | 13.0 | 39.8 | 1,823 | 5.6 | 7,657 | 23.4 | 68.2 |

| 1990 | 391 | 2,634 | 6.7 | 22.2 | 56.8 | 3,233 | 8.3 | 12,892 | 33.0 | 73.2 |

| 1995 | 387 | 5,117 | 13.2 | 29.8 | 77.0 | 4,974 | 12.9 | 18,599 | 48.1 | 90.3 |

| 2000 | 273 | 10,787 | 39.5 | 31.9 | 116.8 | 5,662 | 20.7 | 20,001 | 73.3 | 118.6 |

| 2005 | 513 | 10,718 | 20.9 | 45.1 | 87.9 | 8,170 | 15.9 | 26,752 | 52.1 | 111.6 |

| 2010 | 1,410 | 11,578 | 8.2 | 63.2 | 44.8 | 14,025 | 9.9 | 43,792 | 31.1 | 99.9 |

| 1970 to 2010 net change, in % | ||||||||||

| 3,792 | 1,280 | ... | ... | ... | 3,691 | ... | 2,237 | ... | ... | |

| 1975 (post US off gold standard) to 2010 net change, in % | ||||||||||

| 929 | 1,259 | ... | ... | ... | 2,531 | ... | 1,634 | ... | ... | |

Influencing factors

Like most commodities, the price of gold is driven by supply and demand, including speculative demand. However, unlike most other commodities, saving and disposal play larger roles in affecting its price than its consumption. Most of the gold ever mined still exists in accessible form, such as bullion and mass-produced jewelry, with little value over its fine weight—so it is nearly as liquid as bullion, and can come back onto the gold market. At the end of 2006, it was estimated that all the gold ever mined totalled 158,000 tonnes (156,000 long tons; 174,000 short tons).

Given the huge quantity of gold stored above ground compared to the annual production, the price of gold is mainly affected by changes in sentiment, which affects market supply and demand equally, rather than on changes in annual production. According to the World Gold Council, annual mine production of gold over the last few years has been close to 2,500 tonnes. About 2,000 tonnes goes into jewelry, industrial and dental production, and around 500 tonnes goes to retail investors and exchange-traded gold funds.

Central banks

Central banks and the International Monetary Fund play an important role in the gold price. At the end of 2004, central banks and official organizations held 19% of all above-ground gold as official gold reserves. The ten-year Washington Agreement on Gold (WAG), which dates from September 1999, limited gold sales by its members (Europe, United States, Japan, Australia, the Bank for International Settlements and the International Monetary Fund) to less than 400 tonnes a year. In 2009, this agreement was extended for five years, with a limit of 500 tonnes. European central banks, such as the Bank of England and the Swiss National Bank, have been key sellers of gold over this period. In 2014, the agreement was extended another five years at 400 tonnes per year. In 2019 the agreement was not extended again.

Although central banks do not generally announce gold purchases in advance, some, such as Russia, have expressed interest in growing their gold reserves again as of late 2005. In early 2006, China, which only holds 1.3% of its reserves in gold, announced that it was looking for ways to improve the returns on its official reserves. Some bulls hope that this signals that China might reposition more of its holdings into gold, in line with other central banks. Chinese investors began pursuing investment in gold as an alternative to investment in the Euro after the beginning of the Eurozone crisis in 2011. China has since become the world's top gold consumer as of 2013.

The price of gold can be influenced by a number of macroeconomic variables. Such variables include the price of oil, the use of quantitative easing, currency exchange rate movements and returns on equity markets.

| Years | Amount of gold sold by IMF | sold to |

|---|---|---|

| 1970–1971 | "as much gold as IMF bought from South Africa" | |

| 1976–1980 | 50 million ounces (1555 tons) | |

| 1999–2000 | 14 million ounces (435 tons) | |

| 2009–2010 | 13 million ounces (403 tons) | 200 tons to India |

| 10 tons to Sri Lanka | ||

| 10 tons to Bangladesh | ||

| 2 tons to Mauritius | ||

| IMF holds a balance of 2,814.1 metric tons of gold | ||

Hedge against financial stress

Gold, like all precious metals, may be used as a hedge against inflation, deflation or currency devaluation, though its efficacy as such has been questioned; historically, it has not proven itself reliable as a hedging instrument.

| USD/oz | |

|---|---|

| In real terms (PPI) | 725 |

| In real terms (CPI) | 770 |

| Relative to per capita income | 800 |

| Relative to the S&P500 | 900 |

| Versus copper | 1050 |

| Versus crude oil | 1400 |

Jewelry and industrial demand

Jewelry consistently accounts for over two-thirds of annual gold demand. India is the largest consumer in volume terms, accounting for 27% of demand in 2009, followed by China and the USA.

Industrial, dental and medical uses account for around 12% of gold demand. Gold has high thermal and electrical conductivity properties, along with a high resistance to corrosion and bacterial colonization. Jewelry and industrial demand have fluctuated over the past few years due to the steady expansion in emerging markets of middle classes aspiring to Western lifestyles, offset by the financial crisis of 2007–2010.

Gold jewelry recycling

In recent years the recycling of second-hand jewelry has become a multibillion-dollar industry. The term "Cash for Gold" refers to offers of cash for selling old, broken, or mismatched gold jewelry to local and online gold buyers.

War, invasion and national emergency

When dollars were fully convertible into gold via the gold standard, both were regarded as money. However, many people preferred to carry around paper banknotes rather than the somewhat heavier and less divisible gold coins. If people feared their bank would fail, a bank run might result. This happened in the USA during the Great Depression of the 1930s, leading President Roosevelt to impose a national emergency and issue Executive Order 6102 outlawing the "hoarding" of gold by US citizens. There was only one prosecution under the order, and in that case the order was ruled invalid by federal judge John M. Woolsey, on the technical grounds that the order was signed by the President, not the Secretary of the Treasury as required.

Investment vehicles

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Gold as an investment" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Bars

Main article: Gold bars

The most traditional way of investing in gold is by buying bullion gold bars. In some countries, like Canada, Austria, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, these can easily be bought or sold at the major banks. Alternatively, there are bullion dealers that provide the same service. Bars are available in various sizes. For example, in Europe, Good Delivery bars are approximately 400 troy ounces (12 kg). 1 kilogram (32.2 ozt) bars are also popular, although many other weights exist, such as the 10 ozt (310 g), 1 ozt (31 g), 10 g, 100 g, 1 kg, 1 Tael (50 g in China), and 1 Tola (11.3 g).

Bars generally carry lower price premiums than gold bullion coins. However larger bars carry an increased risk of forgery due to their less stringent parameters for appearance. While bullion coins can be easily weighed and measured against known values to confirm their veracity, most bars cannot, and gold buyers often have bars re-assayed. Larger bars also have a greater volume in which to create a partial forgery using a tungsten-filled cavity, which may not be revealed by an assay. Tungsten is ideal for this purpose because it is much less expensive than gold, but has the same density (19.3 g/cm).

Good delivery bars that are held within the London bullion market (LBMA) system each have a verifiable chain of custody, beginning with the refiner and assayer, and continuing through storage in LBMA recognized vaults. Bars within the LBMA system can be bought and sold easily. If a bar is removed from the vaults and stored outside of the chain of integrity, for example stored at home or in a private vault, it will have to be re-assayed before it can be returned to the LBMA chain. This process is described under the LBMA's "Good Delivery Rules".

The LBMA "traceable chain of custody" includes refiners as well as vaults. Both have to meet their strict guidelines. Bullion products from these trusted refiners are traded at face value by LBMA members without assay testing. By buying bullion from an LBMA member dealer and storing it in an LBMA recognized vault, customers avoid the need of re-assaying or the inconvenience in time and expense it would cost. However this is not 100% sure; for example, Venezuela moved its gold because of the political risk for them. And as the past shows, there may be risk even in countries considered democratic and stable; for example in the US in the 1930s gold was seized by the government and legal moving was banned.

Efforts to combat gold bar counterfeiting include kinebars which employ a unique holographic technology and are manufactured by the Argor-Heraeus refinery in Switzerland.

Coins

Gold coins are a common way of owning gold. Bullion coins are priced according to their fine weight, plus a small premium based on supply and demand (as opposed to numismatic gold coins, which are priced mainly by supply and demand based on rarity and condition).

The sizes of bullion coins range from 0.1 to 2 troy ounces (3.1 to 62.2 g), with the 1 troy ounce (31 g) size being most popular and readily available.

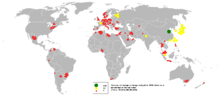

The Krugerrand is the most widely held gold bullion coin, with 46 million troy ounces (1,400 tonnes) in circulation. Other common gold bullion coins include the Australian Gold Nugget (Kangaroo), Austrian Philharmoniker (Philharmonic), Austrian 100 Corona, Canadian Gold Maple Leaf, Chinese Gold Panda, Malaysian Kijang Emas, French Napoleon or Louis d'Or, Mexican Gold 50 Peso, British Sovereign, American Gold Eagle, and American Buffalo.

Coins may be purchased from a variety of dealers both large and small. Fake gold coins are common and are usually made of gold-layered alloys.

Gold rounds

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Gold rounds look like gold coins, but they have no currency value. They range in similar sizes as gold coins, including 0.05 troy ounces (1.6 g), 1 troy ounce (31 g), and larger. Unlike gold coins, gold rounds commonly have no additional metals added to them for durability purposes and do not have to be made by a government mint, which allows the gold rounds to have a lower overhead price as compared to gold coins. On the other hand, gold rounds are normally not as collectible as gold coins.

Exchange-traded products

Gold exchange-traded products may include exchange-traded funds (ETFs), exchange-traded notes (ETNs), and closed-end funds (CEFs), which are traded like shares on the major stock exchanges. The first gold ETF, Gold Bullion Securities (ticker symbol "GOLD"), was launched in March 2003 on the Australian Stock Exchange, and originally represented exactly 0.1 troy ounces (3.1 g) of gold. As of November 2010, SPDR Gold Shares is the second-largest exchange-traded fund in the world by market capitalization.

Gold exchange-traded products (ETPs) represent an easy way to gain exposure to the gold price, without the inconvenience of storing physical bars. However exchange-traded gold instruments, even those that hold physical gold for the benefit of the investor, carry risks beyond those inherent in the precious metal itself. For example, the most popular gold ETP (GLD) has been widely criticized, and even compared with mortgage-backed securities, due to features of its complex structure.

Typically a small commission is charged for trading in gold ETPs and a small annual storage fee is charged. The annual expenses of the fund such as storage, insurance, and management fees are charged by selling a small amount of gold represented by each certificate, so the amount of gold in each certificate will gradually decline over time.

Exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, are investment companies that are legally classified as open-end companies or unit investment trusts (UITs), but that differ from traditional open-end companies and UITs. The main differences are that ETFs do not sell directly to investors and they issue their shares in what are called "Creation Units" (large blocks such as blocks of 50,000 shares). Also, the Creation Units may not be purchased with cash but a basket of securities that mirrors the ETF's portfolio. Usually, the Creation Units are split up and re-sold on a secondary market.

ETF shares can be sold in two ways: The investors can sell the individual shares to other investors, or they can sell the Creation Units back to the ETF. In addition, ETFs generally redeem Creation Units by giving investors the securities that comprise the portfolio instead of cash. Because of the limited redeemability of ETF shares, ETFs are not considered to be and may not call themselves mutual funds.

Certificates

See also: Gold certificate (United States)Gold certificates allow gold investors to avoid the risks and costs associated with the transfer and storage of physical bullion (such as theft, large bid–offer spread, and metallurgical assay costs) by taking on a different set of risks and costs associated with the certificate itself (such as commissions, storage fees, and various types of credit risk).

Banks may issue gold certificates for gold that is allocated (fully reserved) or unallocated (pooled). Unallocated gold certificates are a form of fractional reserve banking and do not guarantee an equal exchange for metal in the event of a run on the issuing bank's gold on deposit. Allocated gold certificates should be correlated with specific numbered bars, although it is difficult to determine whether a bank is improperly allocating a single bar to more than one party.

The first paper bank notes were gold certificates. They were first issued in the 17th century when they were used by goldsmiths in England and the Netherlands for customers who kept deposits of gold bullion in their vault for safe-keeping. Two centuries later, the gold certificates began being issued in the United States when the US Treasury issued such certificates that could be exchanged for gold. The United States Government first authorized the use of the gold certificates in 1863. On April 5, 1933, the US Government restricted the private gold ownership in the United States and therefore, the gold certificates stopped circulating as money (this restriction was reversed on January 1, 1975). Nowadays, gold certificates are still issued by gold pool programs in Australia and the United States, as well as by banks in Germany, Switzerland and Vietnam.

Accounts

Many types of gold "accounts" are available. Different accounts impose varying types of intermediation between the client and their gold. One of the most important differences between accounts is whether the gold is held on an allocated (fully reserved) or unallocated (pooled) basis. Unallocated gold accounts are a form of fractional reserve banking and do not guarantee an equal exchange for metal in the event of a run on the issuer's gold on deposit. Another major difference is the strength of the account holder's claim on the gold, in the event that the account administrator faces gold-denominated liabilities (due to a short or naked short position in gold for example), asset forfeiture, or bankruptcy.

Many banks offer gold accounts where gold can be instantly bought or sold just like any foreign currency on a fractional reserve basis. Swiss banks offer similar service on a fully allocated basis. Pool accounts, such as those offered by some providers, facilitate highly liquid but unallocated claims on gold owned by the company. Digital gold currency systems operate like pool accounts and additionally allow the direct transfer of fungible gold between members of the service. Other operators, by contrast, allows clients to create a bailment on allocated (non-fungible) gold, which becomes the legal property of the buyer.

Other platforms provide a marketplace where physical gold is allocated to the buyer at the point of sale, and becomes their legal property. These providers are merely custodians of client bullion, which does not appear on their balance sheet.

Typically, bullion banks only deal in quantities of 1,000 troy ounces (31 kg) or more in either allocated or unallocated accounts. For private investors, vaulted gold offers private individuals to obtain ownership in professionally vaulted gold starting from minimum investment requirements of several thousand U.S.-dollars or denominations as low as one gram.

Derivatives, CFDs and spread betting

Derivatives, such as gold forwards, futures and options, currently trade on various exchanges around the world and over-the-counter (OTC) directly in the private market. In the U.S., gold futures are primarily traded on the New York Commodities Exchange (COMEX) and Euronext.liffe. In India, gold futures are traded on the National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange (NCDEX) and Multi Commodity Exchange (MCX).

As of 2009 holders of COMEX gold futures have experienced problems taking delivery of their metal. Along with chronic delivery delays, some investors have received delivery of bars not matching their contract in serial number and weight. The delays cannot be easily explained by slow warehouse movements, as the daily reports of these movements show little activity. Because of these problems, there are concerns that COMEX may not have the gold inventory to back its existing warehouse receipts.

Outside the US, a number of firms provide trading on the price of gold via contracts for difference (CFDs) or allow spread bets on the price of gold.

Mining companies

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Instead of buying gold itself, investors can buy the companies that produce the gold as shares in gold mining companies. If the gold price rises, the profits of the gold mining company could be expected to rise and the worth of the company will rise and presumably the share price will also rise. However, there are many factors to take into account and it is not always the case that a share price will rise when the gold price increases. Mines are commercial enterprises and subject to problems such as flooding, subsidence and structural failure, as well as mismanagement, negative publicity, nationalization, theft and corruption. Such factors can lower the share prices of mining companies.

The price of gold bullion is volatile, but unhedged gold shares and funds are regarded as even higher risk and even more volatile. This additional volatility is due to the inherent leverage in the mining sector. For example, if one owns a share in a gold mine where the costs of production are US$300 per troy ounce ($9.6 per gram) and the price of gold is $600 per troy ounce ($19/g), the mine's profit margin will be $300. A 10% increase in the gold price to $660 per troy ounce ($21/g) will push that margin up to $360, which represents a 20% increase in the mine's profitability, and possibly a 20% increase in the share price. Furthermore, at higher prices, more ounces of gold become economically viable to mine, enabling companies to add to their production. Conversely, share movements also amplify falls in the gold price. For example, a 10% fall in the gold price to $540 per troy ounce ($17/g) will decrease that margin to $240, which represents a 20% fall in the mine's profitability, and possibly a 20% decrease in the share price.

To reduce this volatility, some gold mining companies hedge the gold price up to 18 months in advance. This provides the mining company and investors with less exposure to short-term gold price fluctuations, but reduces returns when the gold price is rising.

Investment strategies

Fundamental analysis

Investors using fundamental analysis analyze the macroeconomic situation, which includes international economic indicators, such as GDP growth rates, inflation, interest rates, productivity and energy prices. They would also analyze the yearly global gold supply versus demand.

Gold versus stocks

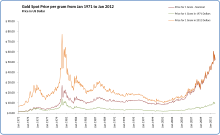

The performance of gold bullion is often compared to stocks as different investment vehicles. Gold is regarded by some as a store of value (without growth) whereas stocks are regarded as a return on value (i.e., growth from anticipated real price increase plus dividends). Stocks and bonds perform best in a stable political climate with strong property rights and little turmoil. The attached graph shows the value of Dow Jones Industrial Average divided by the price of an ounce of gold. Since 1800, stocks have consistently gained value in comparison to gold in part because of the stability of the American political system. This appreciation has been cyclical with long periods of stock outperformance followed by long periods of gold outperformance. The Dow Industrials bottomed out a ratio of 1:1 with gold during 1980 (the end of the 1970s bear market) and proceeded to post gains throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The gold price peak of 1980 also coincided with the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan and the threat of the global expansion of communism. The ratio peaked on January 14, 2000, a value of 41.3 and has fallen sharply since.

One argument follows that in the long-term, gold's high volatility when compared to stocks and bonds, means that gold does not hold its value compared to stocks and bonds:

To take an extreme example , while a dollar invested in bonds in 1801 would be worth nearly a thousand dollars by 1998, a dollar invested in stocks that same year would be worth more than half a million dollars in real terms. Meanwhile, a dollar invested in gold in 1801 would by 1998 be worth just 78 cents.

Using leverage

Investors may choose to leverage their position by borrowing money against their existing assets and then purchasing or selling gold on account with the loaned funds. Leverage is also an integral part of trading gold derivatives and unhedged gold mining company shares (see gold mining companies). Leverage or derivatives may increase investment gains but also increases the corresponding risk of capital loss if the trend reverses.

Taxation

Main article: Taxation of precious metalsGold maintains a special position in the market with many tax regimes. For example, in the United Kingdom and the European Union the trading of recognised gold coins and bullion products are free of VAT. Silver and other precious metals or commodities do not have the same allowance. Other taxes such as capital gains tax may also apply for individuals depending on their tax residency. U.S. citizens may be taxed on their gold profits at collectibles or capital gains rates, depending on the investment vehicle used.

Scams and frauds

Gold attracts various forms of fraudulent activity. Some of the most common are:

- Cash for gold – With the rise in the value of gold due to the financial crisis of 2007–2010, there has been a surge in companies that will buy personal gold in exchange for cash, or sell investments in gold bullion and coins. Several of these have prolific marketing plans and high-value spokesmen, such as prior vice presidents. Many of these companies are under investigation for a variety of securities fraud claims, as well as laundering money for terrorist organizations. Also, given that ownership is often not verified, many companies are considered to be receiving stolen property, and multiple laws are under consideration as methods to curtail this.

- High-yield investment programs – HYIPs are usually just dressed up pyramid schemes, with no real value underneath. Using gold in their prospectus makes them seem more solid and trustworthy.

- Advance fee fraud – Various emails circulate on the Internet for buyers or sellers of up to 10,000 metric tonnes of gold (an amount greater than US Federal Reserve holdings). Through the use of fake legalistic phrases, such as "Swiss Procedure" or "FCO" (Full Corporate Offer), naive middlemen are drafted as hopeful brokers. The end-game of these scams varies, with some attempting to extract a small "validation" amount from the innocent buyer/seller (in hopes of hitting the big deal), and others focused on draining the bank accounts of their targeted dupes.

- Gold dust sellers – This scam persuades an investor to purchase a trial quantity of real gold, then eventually delivers brass filings or similar.

- Counterfeit gold coins.

- Shares in fraudulent mining companies with no gold reserves, or potential of finding gold. For example, the Bre-X scandal in 1997.

- There have been instances of fraud when the seller keeps possession of the gold. In the early 1980s, when gold prices were high, two major frauds were International Gold Bullion Exchange and Bullion Reserve of North America. More recently the 2008 fraud at e-Bullion resulted in a loss for investors, that was only reimbursed to them in April 2019.

See also

- Gold fixing

- Gold repatriation

- Full-reserve banking

- Gold exchange-traded product

- Inflation hedge

- Vaulted gold

- Peak gold

- Gold reserve

- Traditional investments

- Alternative investments

- List of bullion dealers

Rare materials as investments

- Diamonds as an investment

- Palladium as an investment

- Platinum as an investment

- Silver as an investment

References

- Low, R.K.Y.; Yao, Y.; Faff, R. (2015). "Diamonds vs. precious metals: What shines brightest in your investment portfolio?" (PDF). International Review of Financial Analysis. 43: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2015.11.002.

- "World War I - Battles, Facts, Videos & Pictures". History.com.

- "Swiss Narrowly Vote to Drop Gold Standard". The New York Times. Associated Press. April 19, 1999. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- "Gold Price USA". Daily Gold Pro. August 3, 2013. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- LBMA Gold Fixings Archived 2009-03-01 at the Wayback Machine yearly close, rounded to nearest $

- Nominal broad dollar index US Federal Reserve. Gives the comparative international value of the USD against a basket of the currencies of the US's major trading partners. Base date for index (100.0000) was Jan 1997. Index value shown as at June of the relevant year, rounded to nearest 1/10 of a point

- "^DJI Historical Prices | Dow Jones Industrial Average Stock - Yahoo! Finance". Finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- The UN Statistics Division world GDP

- Historical Debt Outstanding – Annual 1950 – 1999 Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine, The Debt to the Penny. Total Public Debt Outstanding (including Intragovernmental Holdings) Archived 2011-04-18 at the Wayback Machine, rounded to nearest billion $

- "Public Debt and Population United States 1970-2010 - Federal State Local Data". www.usgovernmentspending.com. Retrieved Sep 26, 2020.

- "Howstuffworks "All the gold in the world"". Money.howstuffworks.com. April 2000. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "World Gold Council > value > market intelligence > supply & demand > recycled gold". Gold.org. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "World Gold Council". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- "Frequently Asked Questions", World Gold Council, archived from the original on April 20, 2016

- ^ "World Gold Council" (PDF). Gold.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "Official gold reserves". Gold.org. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "400 tonnes/year". Gold.org. September 26, 1999. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- Central banks revive gold bulls, Financial Times, August 8, 2009, archived from the original on August 12, 2009, retrieved June 12, 2010

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "UK Treasury & Central Bank Gold Sales". Bankofengland.co.uk. Archived from the original on May 27, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "A Gold Play on the Dollar's Demise [SPDR Gold Trust (ETF), iShares Gold Trust(ETF), CurrencyShares Euro Trust] - Seeking Alpha". Gold.seekingalpha.com. September 5, 2006. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "China becomes top gold consumer in 2013". Ft.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-25. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-27. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "IMF Gold Sales History". Retrieved Sep 26, 2020.

- "Gold in the IMF". IMF. Retrieved Sep 26, 2020.

- Valenta, Philip (June 22, 2018). "On hedging inflation with gold". Medium. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- Versus long term averages Deutsche Bank Markets Research

- "Demand and supply". World Gold Council. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011.

- "Gold Demand Trends". World Gold Council. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010.

- "Sequels, Nov. 27, 1933". Time. November 27, 1933. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009.

- The Good Delivery Rules for Gold and Silver Bars (PDF), LBMA, May 2010, archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2010, retrieved May 21, 2010

- "LBMA : The Good Delivery Rules for Gold and Silver Bars" (PDF). Lbma.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 7, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Townsend, Erik. "So You Think You Own Gold? Understanding the nuances of paper vs. physical and allocated vs. unallocated metal | Erik Townsend". Financial Sense. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Cancel, Daniel (August 16, 2011). "Venezuela May Move Reserves From U.S. to 'Allied' Countries, Says Lawmaker". Bloomberg. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "China's latest export boom: Fake gold coins". Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- "Should you Buy Bars, Rounds, or Coins?". 14 January 2015.

- "What Is the Difference Between Coins and Rounds?". Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- Ernst, Kelly. "What is a gold ETF?". CBS News. CBS Media. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- "Largest ETFs: Top 25 ETFs By Market Cap". ETFdb. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- Bob Landis (2007), "Musings on the Realms of GLD", The Golden Sextant

- Dave Kranzler (February 12, 2009), "Owning GLD Can Be Hazardous to Your Wealth", Rapid Trends, archived from the original on February 26, 2010, retrieved July 18, 2010

- RunToGold.com (February 19, 2009), "Is the GLD ETF Really Worth Its Metal?", Seeking Alpha

- Jeff Nielson (July 6, 2010), "The Seven Sins of GLD", Bullion Bulls Canada, archived from the original on July 10, 2010, retrieved July 18, 2010

- ^ "Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)". Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Interview: Harvey Organ, Lenny Organ, Adrian Douglas". King World News. April 7, 2010. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010.

- "The economy of Vietnam: gold standard". Vietnam Economics. August 4, 2013. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013.

- Lonergan, Martin (April 19, 2021). "Swiss Banks offer allocated gold".

- "National Commodity & Derivatives Exchange Limited". Dec 1, 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-12-01. Retrieved Sep 26, 2020.

- Nathan Lewis (June 26, 2009), "Where's the gold?", The Huffington Post

- Rosenberg, Dan. "Fundamental analysis: How it can help you determine a stock's value". Britannica Money. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc.

- Investments (7th Ed) by Bodie, Kane and Marcus, P.570-571

- "The Best Inflation Hedge: Gold versus Stocks". GoldRepublic. March 25, 2014. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas (2004). Basic Economics: A Citizen's Guide to the Economy. Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-08145-5.

- "Bullion & VAT Explained". Royal Mint. The Royal Mint.

- Knepp, Tim (January 1, 2010). "Gold taxes". Onwallstreet.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "Glenn Beck Fires Back Over Goldline Investigation - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. July 21, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Stephanie Mencimer. "Goldline Finally Under Investigation". Mother Jones. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Shea, Danny (December 7, 2009). "Glenn Beck's Golden Conflict Of Interest". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Kent, Tom (July 20, 2010). "Glenn Beck's Sponsor Goldline Under Investigation By Los Angeles D.A. For Fraud (VIDEO)". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Aol Money | Personal Finance Comparison, Business News & Market Updates". Dailyfinance.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Kossler, Bill (March 27, 2010). "Cash-for-Gold Businesses Fueling Crime, Police Say". Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- "Look Out for High-Yield Investment Program Scams -- Investor Alert". Investor.gov. Securities and Exchange Commission - US Govt. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- Damon, Dan (July 11, 2004). "Turning the tables on Nigeria's e-mail conmen". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009.

- Joe Wein (June 21, 2011). "Advance Fee Fraud and Fake Lotteries". 419 Scam. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Partridge, Matthew (20 February 2019). "Great frauds in history: the Bre-X gold-mining scandal". Moneyweek. Future plc. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- "Gold and Silver Bullion Bankruptcies, Fraud, Government Actions, etc". about.ag. Retrieved Sep 26, 2020.

- Audit After Gold Dealer's Suicide Suggests Customers Lost Millions New York Times October 5, 1983

- "United States Returns $9.8 Million Recovered from e-Bullion Illegal Money-Transmitting Business to Victims". U.S. Attorney's Office, Central District of California. U.S. Department of Justice. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

External links

Media related to Gold as an investment at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gold as an investment at Wikimedia Commons