Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) or feline interstitial cystitis or cystitis in cats, is one of the most frequently observed forms of feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD). Feline cystitis means "inflammation of the bladder in cats". The term idiopathic means unknown cause; however, certain behaviours have been known to aggravate the illness once it has been initiated. It can affect both males and females of any breed of cat. It is more commonly found in female cats; however, when males do exhibit cystitis, it is usually more dangerous.

Despite the shared terminology, cases of feline idiopathic cystitis, as opposed to human cystitis episodes, are sterile. In other words, they do not involve a primary bacterial infection. If upon investigation the inflammation of the feline bladder is in fact found to be the result of an infection, then it is described as a feline urinary tract infection (UTI) or less commonly, feline bacterial cystitis. In cats under the age of 10 years old, FIC is the most common urinary disease seen in cats and UTIs are very rarely encountered. However, in cats over 10 years of age, UTIs are much more common and idiopathic cases are much less frequently observed. On the other hand, FIC does show several similarities to an analogous disease in humans called bladder pain syndrome.

Signs and symptoms

Feline idiopathic cystitis begins as an acute non-obstructive episode and is self-limiting in about 85% of cases, resolving itself in a week. In approximately 15% of cases, it can escalate into an obstructive episode ("blocked cat") which can be life-threatening for a male cat. The symptoms for both a non-obstructive and an obstructive episode are usually very similar and a careful § differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish between the two.

Non-obstructive FIC

The vast majority of FIC cases are non-obstructive. In the case of non-obstructive FIC, the underlying inflammatory process has begun but the disease has not progressed to the extent that it prevents urination (ie the cat has not "blocked"). Non-obstructive FIC usually resolves spontaneously within 5 to 7 days regardless of treatment. The cat's lower urinary tract is inflamed and the urethral passage may have narrowed due to swelling but it remains open ("patent") and it can urinate to varying degrees, albeit in discomfort. Clinical signs apparent during an acute episode may include:

- Frequent trips to the litter box, possibly with straining due to inflammation triggering urethral spasms.

- Sensation of incomplete voiding.

- Production of small volumes of urine.

- Possible presence of blood in the urine due to glomerulation or Hunner's ulcers.

- Odorous urine.

- Irritability.

- Lack of interest in normal activities.

- Hiding in a dark, quiet location (hiding is part of the cat's stress coping mechanism and should not be interfered with unnecessarily).

- Experiencing pain during the act of urination, characterized by vocalisation. However, since cats are evolutionarily adept at hiding their pain, vocalising, crying, or any other audible cue may not always be observed.

- Reluctance or refusal to urinate due to the pain of excretion. This causes urine to collect in the bladder, similar to that in an obstructive episode. Stagnant urine can become concentrated which promotes § crystal formation, aggravating the risk of § mechanical obstruction (see below).

- Urine leakage if the bladder is not emptied due to overflow incontinence and/or detrusor malfunction (also seen in obstructive episodes). Leaking of urine can also occur due to inflammation of the urinary musculature.

- Loss of appetite and/or refusal to drink due to pain.

- Adopting unusual postures to cope with the pain.

- Urinating in places other than the litter box as the cat associates the pain of urination with the litter box.

- Licking/over-grooming the genital area.

- Lying on cold surfaces, such as tile floors or in showers, in an attempt to relieve pain.

Obstructive FIC ("the blocked cat")

If the acute flare-up of non-obstructive FIC has not resolved itself, it can progress to an obstructive episode in a small number of cases. This is where the urethra can become partially or fully blocked. This is a particular risk for males since they have narrow urethras. Female cats have a larger urethra and rarely become blocked. The following clinical signs may be observed:

- In the case of full obstruction, unproductive and painful straining with either no urine passed at all or isolated drops produced ("spotting") despite frequent trips to the litter box.

- Urinary retention due to incomplete voiding as a result of the obstruction. This means the bladder fills but cannot empty, causing bladder distension (the bladder will feel large and tense).

- Involuntary leaking of urine due to paradoxical incontinence (when drops of urine leak past the obstruction due to pressure building up in the distended bladder).

- Increased pain caused by stagnant urine collecting in the bladder, aggravating underlying inflammation, as well as the increasing distension of the bladder.

- Increased agitation and restlessness.

- Possible vomiting.

- Eventual lethargy and listlessness if a fully obstructive episode progresses, causing risk to life.

A full obstruction is a medical emergency and must be relieved by a vet immediately. Partial obstructions should also be investigated as soon as possible as they are unlikely to resolve themselves and can escalate to full obstruction. Early intervention leads to better prognoses.

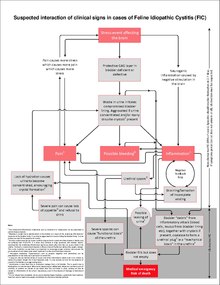

Differential diagnosis of obstructive and non-obstructive cases

See also: Differential diagnosisThe clinical signs in both obstructive and non-obstructive cases can appear very similar to the owner. In particular, stranguria (when a cat strains when urinating), is observed in both cases. The differences between the two cases are discussed below.

| Process | Frequency

of urination |

Volume of

urination |

Bladder

size |

Systemically

unwell |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-obstructive stranguria | Increased | Decreased | Small | Unlikely |

| Obstructive stranguria | Increased | Decreased

to none |

Large | Unlikely |

A vet will often distinguish between obstructive and non-obstructive cases by checking the cat's bladder. A normal, healthy bladder will be semi-full of urine and soft to the touch, like a partially filled balloon. However an inflamed bladder (suggestive of cystitis) will have thickened walls. The bladder muscles have become inflamed and irritated, provoking an involuntary urge to frequently urinate. This can manifest as the straining (ie stranguria) observed as the cat attempts to void. As long as the cat is able to void (even if volumes may be small), the bladder will present as "small" on examination (i.e. very little urine in it due to frequent emptying). This suggests the cat has not (yet) blocked.

However, if the bladder remains distended (ie full of urine), it is considered "large" and together with the obstructive clinical signs listed above, could suggest blockage. The vet will palpate the bladder in an attempt to produce a free-flowing, continuous stream of urine. If this does not occur, a potential obstruction will be suspected and further diagnostics like urinalysis, ultrasound and x-rays may be warranted. However a large bladder and/or the inability to express it is not definitive for blockage. The cat could be resisting the vet's intervention by "pushing back," due to anxiety or a desire to avoid a painful urination.

A less frequently seen intermediate case is where the bladder presents as small but is accompanied by severe straining and frequent attempts at urination. This suggests a possible intermittent spasming of the urethra (ie an "on-off" § functional block) which allows voiding at times when the cat is able to relax himself, but prevents it when the urethral muscles tense involuntarily again. In these instances, the vet may sedate the cat, which relaxes the entire urinary musculature, causing spontaneous urination.

Pathophysiology

Feline idiopathic cystitis is above all an inflammatory process.

Non-obstructive episodes of FIC

Flare-ups of FIC generally begin as non-obstructive incidents. They involve acute inflammation of the lower urinary tract but the cat is still able to urinate. The majority of cases (85%) remain non-obstructive without escalation into blockage and usually resolve themselves within seven days with or without treatment.

Causes

The direct cause of feline idiopathic cystitis is unknown. It is a diagnosis of exclusion which means other possible urinary diseases which could cause bladder inflammation (eg feline urinary tract infections or urolithiasis) are ruled out. Research is still being pursued regarding the causes of cystitis in cats, though the following principal risk factors have been identified:

- Cats predisposed to anxiety or who have a low tolerance to stressors are particularly vulnerable since stress is now considered to be a key factor in triggering acute episodes

- Cats who are neutered or spayed too early

- Cats who are younger/middle-aged (i.e. those less than 10 years old)

- Indoor cats and/or cats who are unable express natural feline behaviour (eg hunting)

- Cats fed a dry food diet who may be inadequately hydrated

- Increased body weight

Treatment of an acute episode

First and foremost, the cat must be kept well hydrated with wet food/soups/broth/increased water intake. This keeps the urine dilute, reducing pain and inflammation, as well as encouraging urination to keep the bladder clear of debris thereby reducing the risk of a § mechanical blockage. Dry food must therefore be avoided. Since the underlying process is inflammation of the bladder, one of the most frequent pharmacological treatments is to administer anti-inflammatory medication. NSAIDs such as meloxicam or robenacoxib are commonly prescribed to control this (provided there are no renal or gastric contraindications). The condition is painful and analgesia (via NSAID or opiates such as buprenorphine) is essential to reduce discomfort and control further stress (which could in turn trigger further inflammation). In the case of a male cat, spasmolytics such as prazosin and/or dantrolene may also be prescribed to control painful urethral spasms and prevent the risk of a § functional blockage. Some research has suggested that prazosin is contraindicated as it leads to recurrent blocking. However this remains strongly contested on the basis of widespread anecdotal evidence showing its effectiveness if administered for at least 10-14 days. If prazosin is not prescribed, some form of anti-spasm medication must be given. In most cases this will be dantrolene. Diazepam is contraindicated as it is associated with harmful side-effects.

Since stress is considered to be a key aggravator in triggering cases of FIC, the most important non-pharmacological/non-dietary intervention is to modify the cat's environment to minimise stressors and improve general well-being (see § environmental modification below). In addition, calming supplements such as tryptophan or alpha-casozepine can also be added to food to improve mood and relaxation.

Oral supplements to reinstate the protective glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer of the bladder (often deficient in cats suffering from FIC) may also be considered. Supplementation with antioxidants and essential fatty acids such as high quality fish oil have also been shown to reduce the severity of the episode. The veterinarian may also use a urine sample from the cat to carry out urinalysis to test for the § presence of crystals which could aggravate the condition (see below).

Within a week most cats should improve spontaneously as the inflammation subsides. However, it is essential to monitor urine output (and compare it to moisture intake) throughout the day, every day, to watch for incipient signs of blocking until the inflammation subsides and the cat returns to good health. Any presumed non-obstructive case which does not resolve itself with seven days should be suspect for obstruction and investigated further.

Obstructive episodes of FIC ("the blocked cat")

Causes

Obstructive episodes occur in the rarer instances (approximately 15% of FIC cases) when the initial, § non-obstructive attack (see above) is not self-limiting and escalates into partial or full block of the urethra. In this case voiding of urine is impeded or altogether impossible. Obstruction occurs almost exclusively in male cats due to their long, narrow urethra. There are two reasons why a cat may obstruct ("block"):

Functional blockage

The block can be functional. This occurs when a severe muscle spasm of the urethra occurs to close it shut (like cramping). Unless the cat is unable to relax itself again to regain normal function, it cannot urinate. It is intensely painful and is triggered by the underlying inflammation, itself suspected to be caused by the stress of the condition. Effectively the cat involuntarily "blocks himself".

Mechanical blockage

A mechanical block occurs when actual physical particles obstruct the urethra. In 80% of such cases, a urethral plug composed of material generated from the underlying bladder inflammation (eg blood cells, mucus), called matrix, combines with struvite crystals in the bladder to form a hardened obstruction. In a small number of cases, the plug will be composed of matrix alone if no crystals are present.

Interaction between functional and mechanical blockage in FIC

Both functional and mechanical blocks can negatively interact to fully obstruct the cat rapidly. The underlying inflammation can narrow the urethral opening as well as provoking spasming to cause the walls of the urethra to close shut around a urethral plug forming in it. For this reason an anti-spasmodic drug such as prazosin or dantrolene is often advised as it will prevent spasming of the urethra and allow any incipient plug to pass during urinating before it is fully formed and causes obstruction.

The role of crystals in obstructive FIC

Crystalluria is the presence of microscopic crystals in feline urine. These are most often struvite precipitates but other minerals such as calcium oxalate crystals are also found, albeit less frequently. Urinary crystals are not necessarily an abnormal finding and can be seen both in cats who are healthy and those who are suffering from a urinary tract illness. However, they can be a risk factor for cats suffering from urinary disease. Whilst crystals (as opposed to uroliths) do not alone cause a urethral obstruction, they aggravate the risk of it since they are usually one of the components of a urethral plug which is responsible for § mechanical blockage in obstructive episodes. The normal pH of feline urine is around 6.5. However struvite crystals tend to form in concentrated, alkaline urine when the pH is greater than 6.5. Therefore stress (which can cause alkalinity) or supersaturated urine (caused by lack of hydration or by stagnant urine collecting in the bladder due to urinary retention) both encourage crystal formation.

Struvite crystalluria can be managed by regulating the urine pH so it stays around 6.5. A urinalysis is necessary to determine if the pH is excessively alkaline and a high quality wet meat diet with added acidifiers can be fed to lower the pH (prescription diets achieve a similar effect). However continuous monitoring of the urine should be undertaken as excessive urine acidity can lead to calcium oxalate formation which cannot be managed via diet but can also lead to obstruction if unchecked. Regular urinalysis will indicate the nature and extent of crystal formation, together with urine pH, to determine if there are any areas of possible concern which need to be addressed.

Treatment of an acute episode

Veterinary attention is essential if urine does not pass at all as the bladder could rupture and there is risk of death within 72 hours. The vet will usually attempt to relieve the blockage with a catheter, draining the backed-up urine and flush the bladder of any sediment (this may include crystals). This is an invasive, delicate procedure which will require either heavy sedation or general anaesthetic. The cat should then be hospitalised with the catheter in place and hydration administered intravenously to encourage healthy urination and good kidney function, ideally for three days. While the catheter is in place, intravesical instillation (which is also used to treat human interstitial cystitis) may also be administered to repair the compromised bladder lining. When the catheter is removed, the cat must be able to show he can urinate with good function before he can be discharged. With this proviso, he can return home and the anti-inflammatory and anti-spasm medication indicated for non-obstructive cases will be prescribed, as well as oral supplements to calm the cat and replenish the protective bladder lining (see above). Medication should be given for long enough to ensure symptoms properly subside at which point it should be slowly tapered off. This can usually take around 10 - 14 days but could take longer. Stopping medication too early can result in re-blocking.

Even after the cat is unblocked, the underlying inflammatory syndrome will continue for some days at home (particularly since the catheter itself will have irritated the urethra). Therefore, some of the clinical signs for non-obstructive FIC may still be apparent post-discharge until the inflammation subsides and cat has fully recovered (eg frequent voiding, blood in urine, possible leaking). However medication should alleviate the severity and discomfort as well as assisting recovery. The owner must focus above all on good hydration (from a wet food diet if the cat will accept it) and frequent urination to keep the bladder clear. Wet prescription diets may be recommended but if the cat refuses this (cats often avoid eating unfamiliar food when stressed), any high quality, high moisture, high animal protein wet food which the cat finds appealing may be administered. A urinary acidifier (e.g. DL-Methionine) may be added to the latter to prevent struvite crystal formation but as animal protein is already acidic, it is not strictly necessary. In any case, excessive acidification should be balanced against the risk that it could irritate the inflamed bladder wall. This could trigger recrudescence ie a further acute attack, as well as encouraging calcium oxalate crystal formation which forms in highly acidic urine. An acidifier should never be added to prescription urinary food as this has already been acidified. Acidification or prescription foods are always secondary to the first priority of good hydration from any wet food the cat finds palatable. Dry food of any sort (including prescription dry food) should be avoided.

Environmental modification to reduce stress, itself suspected to be one of the principal causes of FIC, must also be considered (see below) as the risk of re-blocking is highest within the first week after catheterisation.

Secondary bacterial infection (UTI) after an obstructive episode

Whereas primary feline urinary tract infections are rare in younger male cats, when a cat suffers an obstructive episode of FIC which has involved catheterisation and/or the symptomatic presence of crystals, then a secondary urinary tract infection becomes more likely as a follow-on complication. The symptoms of bacterial infection in the lower urinary tract are very similar to those for non-obstructive FIC (ie straining, blood in urine etc) and a urine test with cultures will be needed to detect if an infection is present. Treatment is usually effective with antibiotics once the result of the urine culture identifies the precise bacteria involved in the infection. D-mannose (which is also anti-inflammatory) is also used by some pet owners as a natural alternative to antibiotic treatment although this may be less targeted and specific than prescribed antibiotics following a urine culture. Probiotics should be considered after a course of antibiotics to avoid any digestive distress and to allow beneficial gut flora to recolonise which is essential to feline immunity.

Ongoing management of FIC

Since feline idiopathic cystitis is commonly known to reoccur, ongoing precautions need to be taken to avoid relapse.

Importance of hydration

As domestic cats are descended from their desert-inhabiting ancestors, they instinctively seek moisture from their prey. High quality wet food is the most natural way therefore to hydrate a cat as drinking water from a bowl is arguably species-inappropriate since anatomical limitations in the cat's tongue restrict the amount of water they can ingest this way. Drinking still water from a bowl (particularly tap as opposed to rain water) is often a last resort for many cats and some may avoid it altogether. A quality wet food diet will therefore be most effective in ensuring sufficient moisture intake and will always be more effective than dry food in hydrating a cat, even when any additional moisture intake from drinking water is taken into account.

Supplementing wet food with antioxidants and essential fatty acids such as high quality fish oil have also been shown to reduce the severity and recurrence of FIC episodes.

Environmental modification

Together with hydration, improvements to the cat's environment have been shown to prevent relapses. Reducing stress and encouraging natural feline behaviour (particularly for indoor cats) is essential. Suggested methods include:

- No sudden disruption to routine or changes in a cat's environment.

- Olfactory enrichment with indoor cat-safe plants (eg cat grass, catnip, silver vine or cat thyme) can again replicate a pleasing, natural environment indoors.

- Outdoor visits (supervised in the case of indoor cats) will encourage sensory stimulation and defeat boredom which could lead to stress.

- Window sill perches (particularly if they look out onto a natural landscape with wildlife and birds) provide important visual stimulation, particularly for cats who have no outdoor access. Ideally the perches should be affixed to windows which provide good visibility of the surrounding outdoor space (windows on lower floors of a building work better therefore than those on floors which are too high up). Perches should be affixed at a variety of locations to offer diverse vantage points.

- Maintaining close contact with owners and avoiding extended periods of isolation to prevent separation anxiety. This is particularly important for rescued strays or abandoned cats who have since been re-homed in an environment they perceive as safe..

- Play with owners in short bursts de-stresses a cat and stimulates positive neural activity.

- Regular rotation and replacement of cat toys.

- Safe, enclosed, quiet sleeping areas such as igloo beds.

- Avoidance of sudden or loud noises which could adversely trigger the startle response (classical music or special "Cat Music" in the background can be used to mitigate this).

- Litter tray hygiene and availability.

Surgical intervention for refractory cases

For recurrent cases of FIC in male cats where blockage is a risk, and dietary and environmental modifications have not prevented relapse, a last line of treatment to prevent future obstruction is surgery to widen the male urethra. This is called Perineal Urethrostomy (PU) but brings with it other risks and should therefore only be considered once all other options have been exhausted.

References

- Cannon M, Forster-van Hijfte M (2006). Feline Medicine: a practical guide for veterinary nurses and technicians. Elsevier Sciences. ISBN 9780750688277.

- "Cat Urinary Tract Problems". Purina.

- Longstaff L, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Buffington CT, Casey RA, Murray JK (June 2017). "Owner-reported lower urinary tract signs in a cohort of young cats". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 19 (6): 609–618. doi:10.1177/1098612X16643123. hdl:1983/a703d62a-8b70-4bf8-94be-5fd215db58f5. PMID 27102690. S2CID 206693086.

- ^ Chew D (2007-08-19). "Non-obstructive Idiopathic/Interstitial Cystitis in Cats: Thinking Outside the (Litter) Box". World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2007.

- ^ Cook JL, Arnoczky SP (2015-03-30). "World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2013". VIN.com.

- Treutlein G, Deeg CA, Hauck SM, Amann B, Hartmann K, Dorsch R (December 2013). "Follow-up protein profiles in urine samples during the course of obstructive feline idiopathic cystitis". Veterinary Journal. 198 (3): 625–30. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.015. PMID 24257070.

- James L. Cook1, D. V. M.; Steven P. Arnoczky2, D. V. M. (2015-03-30). "World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2013". VIN.com.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sands D (2005). Cats 500 questions answered. Barnes and Noble. ISBN 9780600611790.

- Clasper M (December 1990). "A case of interstitial cystitis and Hunner's ulcer in a domestic shorthaired cat". New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 38 (4): 158–60. doi:10.1080/00480169.1990.35644. PMID 16031604.

- ^ Bovens C (2011). "Feline Urinary Tract Disease: A diagnostic approach" (PDF). Feline Update (Langford Feline Centre at the University of Bristol).

- "Urinary incontinence in cats | Vetlexicon Felis from Vetstream | Definitive Veterinary Intelligence". www.vetstream.com. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- BSAVA manual of canine and feline nephrology and urology. Jonathan, MRCVS Elliott, Gregory F. Grauer, Jodi L. Westropp, British Small Animal Veterinary Association (Third ed.). Gloucester. 2017. ISBN 978-1-910443-35-4. OCLC 1011666365.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Grauer GF (November 2013). "Current Thoughts on Pathophysiology and Treatment of Feline Idiopathic Cystitis". Today's Veterinary Practice. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Sævik BK, Trangerud C, Ottesen N, Sørum H, Eggertsdóttir AV (June 2011). "Causes of lower urinary tract disease in Norwegian cats". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 13 (6): 410–7. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2010.12.012. PMC 10832705. PMID 21440473. S2CID 5186889.

- Cameron ME, Casey RA, Bradshaw JW, Waran NK, Gunn-Moore DA (March 2004). "A study of environmental and behavioural factors that may be associated with feline idiopathic cystitis". The Journal of Small Animal Practice. 45 (3): 144–7. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2004.tb00216.x. PMID 15049572.

- ^ Wooten S. "Feline interstitial cystitis: It's not about the bladder". DVM 360. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Stevenson, Abigail (13 October 2011). "Scientists discover dietary moisture window that boosts urinary tract health in cats" (PDF). WALTHAM Centre for Pet Nutrition. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Lund HS, Krontveit RI, Halvorsen I, Eggertsdóttir AV (December 2013). "Evaluation of urinalyses from untreated adult cats with lower urinary tract disease and healthy control cats: predictive abilities and clinical relevance". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 15 (12): 1086–97. doi:10.1177/1098612X13492739. PMC 10816473. PMID 23783431. S2CID 206691916.

- "Feeding Your Cat: Know the Basics of Feline Nutrition – Common Sense. Healthy Cats". catinfo.org. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ Bovens C (2012). "Feline Idiopathic Cystitis". Feline Update at Langford Feline Centre (University of Bristol).

- Conway, David S.; Rozanski, Elizabeth A.; Wayne, Annie S. (2022-05-21). "Prazosin administration increases the rate of recurrent urethral obstruction in cats: 388 cases". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 260 (S2): S7 – S11. doi:10.2460/javma.21.10.0469. ISSN 1943-569X. PMID 35290210.

- "The role of L-tryptophan/alpha-casozepine". veterinary-practice.com. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- ^ Kruger JM, Osborne CA, Lulich JP (January 2009). "Changing paradigms of feline idiopathic cystitis". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice. 39 (1): 15–40. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.09.008. PMID 19038648.

- Pawprints and Purr Incorporated. "Feline Cystitis". Feline Cystitis

- "Urethral obstruction in cats | International Cat Care". icatcare.org. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- "Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease (FLUTD) | International Cat Care". icatcare.org. Retrieved 2020-10-11.

- Buffington, C. A.; Chew, D. J. (1996). "Intermittent alkaline urine in a cat fed an acidifying diet". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 209 (1): 103–104. PMID 8926188.

- Publishing, Harvard Health (20 July 2011). "Diagnosing and treating interstitial cystitis". Harvard Health. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- "Bladder Instillation of Cystistat (sodium hyaluronate) – East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust". Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- "Cystistat® for your interstitial cystitis" (PDF). Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Trust. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Bladder Instillations". Interstitial Cystitis Association. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- Bradley AM, Lappin MR (June 2014). "Intravesical glycosaminoglycans for obstructive feline idiopathic cystitis: a pilot study". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 16 (6): 504–6. doi:10.1177/1098612X13510918. PMC 11112186. PMID 24196569. S2CID 12966706.

- "A-Cyst for Animal Use". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- "Feeding your Cat or Kitten | International Cat Care". icatcare.org. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Litster A, Thompson M, Moss S, Trott D (January 2011). "Feline bacterial urinary tract infections: An update on an evolving clinical problem". Veterinary Journal. 187 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.12.006. PMID 20044282.

- Staff, Today's Veterinary Business (2020-01-23). "Purina sees Hydra Care as dehydration solution". Today's Veterinary Business. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- Buffington CA, Westropp JL, Chew DJ, Bolus RR (August 2006). "Clinical evaluation of multimodal environmental modification (MEMO) in the management of cats with idiopathic cystitis". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 8 (4): 261–8. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2006.02.002. PMC 10822542. PMID 16616567. S2CID 33415205.

- Stella J, Croney C, Buffington T (January 2013). "Effects of stressors on the behavior and physiology of domestic cats". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. Special Issue: Laboratory Animal Behaviour and Welfare. 143 (2–4): 157–163. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2012.10.014. PMC 4157662. PMID 25210211.

- Bol S, Caspers J, Buckingham L, Anderson-Shelton GD, Ridgway C, Buffington CA, et al. (March 2017). "Responsiveness of cats (Felidae) to silver vine (Actinidia polygama), Tatarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica), valerian (Valeriana officinalis) and catnip (Nepeta cataria)". BMC Veterinary Research. 13 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/s12917-017-0987-6. PMC 5356310. PMID 28302120.

- Buffington, C. A. Tony (2002-04-01). "External and internal influences on disease risk in cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 220 (7): 994–1002. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.994. ISSN 0003-1488. PMID 12420776.

- "Feline Idiopathic Cystitis" (PDF). www.thecatclinic.ca.

- "Why do cats love sleeping in cardboard boxes? Scientists may have the answer". The Independent. 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- "Perineal Urethrostomy Surgery in Cats". vca_corporate. Retrieved 2020-12-02.