The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid, Europid, or Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The Caucasian race was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, depending on which of the historical race classifications was being used, usually included ancient and modern populations from all or parts of Europe, Western Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa.

Introduced in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history, the term denoted one of three purported major races of humankind (those three being Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid). In biological anthropology, Caucasoid has been used as an umbrella term for phenotypically similar groups from these different regions, with a focus on skeletal anatomy, and especially cranial morphology, without regard to skin tone. Ancient and modern "Caucasoid" populations were thus not exclusively "white", but ranged in complexion from white-skinned to dark brown.

Since the second half of the 20th century, physical anthropologists have switched from a typological understanding of human biological diversity towards a genomic and population-based perspective, and have tended to understand race as a social classification of humans based on phenotype and ancestry as well as cultural factors, as the concept is also understood in the social sciences.

In the United States, the root term Caucasian is still in use as a synonym for white or of European, Middle Eastern, or North African ancestry, a usage that has been criticized.

History of the concept

The Caucasus as the origin of humanity and the peak of beauty

In the eighteenth century, the prevalent view among European scholars was that the human species had its origin in the region of the Caucasus Mountains. This view was based upon the Caucasus being the location for the purported landing point of Noah's Ark – from whom the Bible states that humanity is descended – and the location for the suffering of Prometheus, who in Hesiod's myth had crafted humankind from clay.

In addition, the most beautiful humans were reputed by Europeans to be the stereotypical "Circassian beauties" and the Georgian people; both Georgia and Circassia are in the Caucasus region. The "Circassian beauty" stereotype had its roots in the Middle Ages, while the reputation for the attractiveness of the Georgian people was developed by early modern travellers to the region such as Jean Chardin.

Göttingen school of history

The term Caucasian as a racial category was introduced in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history – notably Christoph Meiners in 1785 and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in 1795—it had originally referred in a narrow sense to the native inhabitants of the Caucasus region.

In his The Outline of History of Mankind (1785), the German philosopher Christoph Meiners first used the concept of a "Caucasian" (Kaukasisch) race in its wider racial sense. Meiners' term was given wider circulation in the 1790s by many people. Meiners imagined that the Caucasian race encompassed all of the ancient and most of the modern native populations of Europe, the aboriginal inhabitants of West Asia (including the Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arabs), the autochthones of Northern Africa (Berbers, Egyptians, Abyssinians and neighboring groups), the Indians, and the ancient Guanches.

It was Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a colleague of Meiners', who later came to be considered one of the founders of the discipline of anthropology, who gave the term a wider audience, by grounding it in the new methods of craniometry and Linnean taxonomy. Blumenbach did not credit Meiners with his taxonomy, although his justification clearly points to Meiners' aesthetic viewpoint of Caucasus origins. In contrast to Meiners, however, Blumenbach was a monogenist—he considered all humans to have a shared origin and to be a single species. Blumenbach, like Meiners, did rank his Caucasian grouping higher than other groups in terms of mental faculties or potential for achievement despite pointing out that the transition from one race to another is so gradual that the distinctions between the races presented by him are "very arbitrary".

Alongside the anthropologist Georges Cuvier, Blumenbach classified the Caucasian race by cranial measurements and bone morphology in addition to skin pigmentation. Following Meiners, Blumenbach described the Caucasian race as consisting of the native inhabitants of Europe, West Asia, the Indian peninsula, and North Africa. This usage later grew into the widely used color terminology for race, contrasting with the terms Negroid, Mongoloid, and Australoid.

Carleton Coon

There was never consensus among the proponents of the "Caucasoid race" concept regarding how it would be delineated from other groups such as the proposed Mongoloid race. Carleton S. Coon (1939) included the populations native to all of Central and Northern Asia, including the Ainu people, under the Caucasoid label. However, many scientists maintained the racial categorizations of color established by Meiners' and Blumenbach's works, along with many other early steps of anthropology, well into the late 19th and mid-to-late 20th centuries, increasingly used to justify political policies, such as segregation and immigration restrictions, and other opinions based in prejudice. For example, Thomas Henry Huxley (1870) classified all populations of Asian nations as Mongoloid. Lothrop Stoddard (1920) in turn classified as "brown" most of the populations of the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, Central Asia and South Asia. He counted as "white" only European peoples and their descendants, as well as a few populations in areas adjacent to or opposite southern Europe, in parts of Anatolia and parts of the Rif and Atlas mountains.

In 1939, Coon argued that the Caucasian race had originated through admixture between Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens of the "Mediterranean type" which he considered to be distinct from Caucasians, rather than a subtype of it as others had done. While Blumenbach had erroneously thought that light skin color was ancestral to all humans and the dark skin of southern populations was due to sun, Coon thought that Caucasians had lost their original pigmentation as they moved North. Coon used the term "Caucasoid" and "White race" synonymously.

In 1962, Coon published The Origin of Races, wherein he proposed a polygenist view, that human races had evolved separately from local varieties of Homo erectus. Dividing humans into five main races, and argued that each evolved in parallel but at different rates, so that some races had reached higher levels of evolution than others. He argued that the Caucasoid race had evolved 200,000 years prior to the "Congoid race", and hence represented a higher evolutionary stage.

Coon argued that Caucasoid traits emerged prior to the Cro-Magnons, and were present in the Skhul and Qafzeh hominids. However, these fossils and the Predmost specimen were held to be Neanderthaloid derivatives because they possessed short cervical vertebrae, lower and narrower pelves, and had some Neanderthal skull traits. Coon further asserted that the Caucasoid race was of dual origin, consisting of early dolichocephalic (e.g. Galley Hill, Combe-Capelle, Téviec) and Neolithic Mediterranean Homo sapiens (e.g. Muge, Long Barrow, Corded), as well as Neanderthal-influenced brachycephalic Homo sapiens dating to the Mesolithic and Neolithic (e.g. Afalou, Hvellinge, Fjelkinge).

Coon's theories on race were much disputed in his lifetime, and are considered pseudoscientific in modern anthropology.

Criticism based on modern genetics

See also: Race and geneticsAfter discussing various criteria used in biology to define subspecies or races, Alan R. Templeton concludes in 2016: "he answer to the question whether races exist in humans is clear and unambiguous: no."

Racial anthropology

Armenian man of Armenoid type

Armenian man of Armenoid type Irish man of Mediterranean type

Irish man of Mediterranean type Bisharin man of Hamitic type

Bisharin man of Hamitic type Afghan man of Iranid type

Afghan man of Iranid type Danish man of Nordic type

Danish man of Nordic type Tajik man of Alpine type

Tajik man of Alpine type Hindu man of 'mixed' Aryan type

Hindu man of 'mixed' Aryan type Catalan man of Iberian typeIllustrations of "Caucasoid subraces" from Man, Past and Present by Augustus Henry Keane (1899)

Catalan man of Iberian typeIllustrations of "Caucasoid subraces" from Man, Past and Present by Augustus Henry Keane (1899)

Physical traits

Skull and teeth

Drawing from Petrus Camper's theory of facial angle, Blumenbach and Cuvier classified races, through their skull collections based on their cranial features and anthropometric measurements. Caucasoid traits were recognised as: thin nasal aperture ("nose narrow"), a small mouth, facial angle of 100–90°, and orthognathism, exemplified by what Blumenbach saw in most ancient Greek crania and statues. Later anthropologists of the 19th and early 20th century such as James Cowles Prichard, Charles Pickering, Broca, Paul Topinard, Samuel George Morton, Oscar Peschel, Charles Gabriel Seligman, Robert Bennett Bean, William Zebina Ripley, Alfred Cort Haddon and Roland Dixon came to recognize other Caucasoid morphological features, such as prominent supraorbital ridges and a sharp nasal sill. Many anthropologists in the 20th century used the term "Caucasoid" in their literature, such as William Clouser Boyd, Reginald Ruggles Gates, Carleton S. Coon, Sonia Mary Cole, Alice Mossie Brues and Grover Krantz replacing the earlier term "Caucasian" as it had fallen out of usage.

Classification

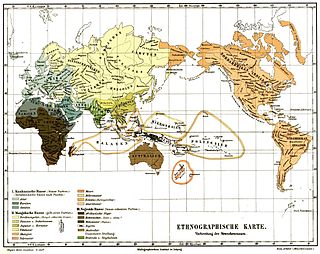

| Caucasoid: Aryans Semitic Hamitic Negroid: African Negro Khoikhoi Melanesian Negrito Australoid Uncertain: Dravida & Sinhalese | Mongoloid: North Mongol Chinese & Indochinese Korean & Japanese Tibetan & Burmese Malay Polynesian Maori Micronesian Eskimo & Inuit American |

In the 19th century Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (1885–1890), Caucasoid was one of the three great races of humankind, alongside Mongoloid and Negroid. The taxon was taken to consist of a number of subtypes. The Caucasoid peoples were usually divided into three groups on ethnolinguistic grounds, termed Aryan (Indo-European), Semitic (Semitic languages), and Hamitic (Hamitic languages i.e. Berber-Cushitic-Egyptian).

19th century classifications of the peoples of India were initially uncertain if the Dravidians and the Sinhalese were Caucasoid or a separate Dravida race, but by and in the 20th century, anthropologists predominantly declared Dravidians to be Caucasoid.

Historically, the racial classification of the Turkic peoples was sometimes given as "Turanid". Turanid racial type or "minor race", subtype of the Europid (Caucasian) race with Mongoloid admixtures, situated at the boundary of the distribution of the Mongoloid and Europid "great races".

There was no universal consensus of the validity of the "Caucasoid" grouping within those who attempted to categorize human variation. Thomas Henry Huxley in 1870 wrote that the "absurd denomination of 'Caucasian'" was in fact a conflation of his Xanthochroi (Nordic) and Melanochroi (Mediterranean) types.

Subraces

The postulated subraces vary depending on the author, including but not limited to Mediterranean, Atlantid, Nordic, East Baltic, Alpine, Dinaric, Turanid, Armenoid, Iranid, Indid, Arabid, and Hamitic. Some authors also proposed a Pamirid race (or Pamir-Fergana race) in Central Asia, named after the Pamir range and the Fergana valley.

H.G. Wells argued that across Europe, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, West Asia, Central Asia and South Asia, a Caucasian physical stock existed. He divided this racial element into two main groups: a shorter and darker Mediterranean or Iberian race and a taller and lighter Nordic race. Wells asserted that Semitic and Hamitic populations were mainly of Mediterranean type, and Aryan populations were originally of Nordic type. He regarded the Basques as descendants of early Mediterranean peoples, who inhabited western Europe before the arrival of Aryan Celts from the direction of central Europe.

The "Northcaucasian race" is a sub-race proposed by Carleton S. Coon (1930). It comprises the native populations of the North Caucasus, the Balkars, Karachays and Vainakh (Chechens and Ingushs).

An introduction to anthropology, published in 1953, gives a more complex classification scheme:

- "Archaic Caucasoid Races": Ainu people in Japan, Australoid race, Dravidian peoples, and Vedda

- "Primary Caucasoid Races": Alpine race, Armenoid race, Mediterranean race, and Nordic race

- "Secondary or Derived Caucasoid Races": Dinaric race, East Baltic race, and Polynesian race

Usage in the United States

Further information: Race in the United StatesBesides its use in anthropology and related fields, the term "Caucasian" has often been used in the United States in a different, social context to describe a group commonly called "white people". "White" also appears as a self-reporting entry in the U.S. Census. Naturalization as a United States citizen was restricted to "free white persons" by the Naturalization Act of 1790, and later extended to other resident populations by the Naturalization Act of 1870, Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 and Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. The Supreme Court in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923) decided that Asian Indians were ineligible for citizenship because, though deemed "Caucasian" anthropologically, they were not white like European descendants since most laypeople did not consider them to be "white" people. This represented a change from the Supreme Court's earlier opinion in Ozawa v. United States, in which it had expressly approved of two lower court cases holding "high caste Hindus" to be "free white persons" within the meaning of the naturalization act. Government lawyers later recognized that the Supreme Court had "withdrawn" this approval in Thind. In 1946, the U.S. Congress passed a new law establishing a small immigration quota for Indians, which also permitted them to become citizens. Major changes to immigration law, however, only later came in 1965, when many earlier racial restrictions on immigration were lifted. This resulted in confusion about whether American Hispanics are included as "white", as the term Hispanic originally applied to Spanish heritage but has since expanded to include all people with origins in Spanish speaking countries. In other countries, the term Hispanic is rarely used.

The United States National Library of Medicine often used the term "Caucasian" as a race in the past. However, it later discontinued such usage in favor of the more narrow geographical term European, which traditionally only applied to a subset of Caucasoids.

See also

- Race (human categorization)

- Race and genetics

- Anthropometry

- Leucism

- Race and ethnicity in the United States Census

Notes

- The traditional anthropological term Caucasoid is a conflation of the demonym Caucasian and the Greek suffix eidos (meaning "form", "shape", "resemblance") implying a resemblance to the native inhabitants of the Caucasus. It etymologically contrasts with the terms Negroid, Mongoloid and Australoid. For a contrast with the "Mongolic" or Mongoloid race, see footnote #4 pp. 58–59 in Beckwith, Christopher (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2. OCLC 800915872.

- ^ Cited by contributing editor to a group of four works by Baum, Woodward, Rupke, and Simon.

- Cited by contributing editor to a group of nine works by Mario, Isaac, Schiebinger, Rupp-Eisenreich, Dougherty, Hochman, Mikkelsen, Painter, and Binden.

References

- Freedman, B. J. (1984). "For debate... Caucasian". British Medical Journal. 288 (6418). Routledge: 696–98. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6418.696. PMC 1444385. PMID 6421437.

- Pearson, Roger (1985). Anthropological glossary. R. E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 79. ISBN 9780898745108. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Templeton, A. (2016). "Evolution and Notions of Human Race". In Losos, J.; Lenski, R. (eds.). How Evolution Shapes Our Lives: Essays on Biology and Society. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. pp. 346–361. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0s6j.26.

... the answer to the question whether races exist in humans is clear and unambiguous: no.

- Wagner, Jennifer K.; Yu, Joon-Ho; Ifekwunigwe, Jayne O.; Harrell, Tanya M.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Royal, Charmaine D. (February 2017). "Anthropologists' views on race, ancestry, and genetics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (2): 318–327. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23120. PMC 5299519. PMID 27874171.

- American Association of Physical Anthropologists (March 27, 2019). "AAPA Statement on Race and Racism". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Coon, Carleton Stevens (1939). The Races of Europe. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 400–401.

This third racial zone stretches from Spain across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco, and thence along the southern Mediterranean shores into Arabia, East Africa, Mesopotamia, and the Persian highlands; and across Afghanistan into India The Mediterranean racial zone stretches unbroken from Spain across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco, and thence eastward to India A branch of it extends far southward on both sides of the Red Sea into southern Arabia, the Ethiopian highlands, and the Horn of Africa.

- Coon, Carleton Stevens; Hunt, Edward E. (1966). The Living Races of Man. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 93.

Late Capsians from North Africa are clearly Caucasoid and, more specifically, almost entirely Mediterranean.

- Baum 2006, pp. 84–85: "Finally, Christoph Meiners (1747–1810), the University of Göttingen 'popular philosopher' and historian, first gave the term Caucasian racial meaning in his Grundriss der Geschichte der Menschheit (Outline of the History of Humanity; 1785) ... Meiners pursued this 'Göttingen program' of inquiry in extensive historical-anthropological writings, which included two editions of his Outline of the History of Humanity and numerous articles in Göttingisches Historisches Magazin"

- William R. Woodward (June 9, 2015). Hermann Lotze: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-316-29785-8.

... the five human races identified by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach – Negroes, American Indians, Malaysians, Mongolians, and Caucasians. He chose to rely on Blumenbach, leader of the Göttingen school of comparative anatomy

- Nicolaas A. Rupke (2002). Göttingen and the Development of the Natural Sciences. Wallstein-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89244-611-8.

For it was at Gottingen in this period that the outlines of a system of classification were laid down in a manner that still shapes the way in which we attempt to comprehend the different varieties of humankind – including usage of such terms as 'Caucasian'.

- Charles Simon-Aaron (2008). The Atlantic Slave Trade: Empire, Enlightenment, and the Cult of the Unthinking Negro. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-5197-1.

Here, Blumenbach placed the white European at the apex of the human family; he even gave the European a new name – i.e., Caucasian. This relationship also inspired the academic labors of Karl Otfried Muller, C. Meiners and K. A. Heumann, the more important thinkers at Gottingen for our project. (This list is not intended to be exhaustive.)

- Pickering, Robert (2009). The Use of Forensic Anthropology. CRC Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4200-6877-1.

- Pickering, Robert (2009). The Use of Forensic Anthropology. CRC Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4200-6877-1.

- Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1865). Thomas Bendyshe (ed.). The Anthropological Treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Anthropological Society. pp. 265, 303, 367. ISBN 9780878211241.

- ^ Caspari, Rachel (2003). "From types to populations: A century of race, physical anthropology, and the American Anthropological Association" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 105 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.65. hdl:2027.42/65890.

- "Race".

- Bhopal, R.; Donaldson, L. (1998). "White, European, Western, Caucasian, or what? Inappropriate labeling in research on race, ethnicity, and health". American Journal of Public Health. 88 (9): 1303–1307. doi:10.2105/ajph.88.9.1303. PMC 1509085. PMID 9736867.

- Baum 2006, p. 3,18.

- Herbst, Philip (June 15, 1997). The color of words: an encyclopaedic dictionary of ethnic bias in the United States. Intercultural Press. ISBN 978-1-877864-97-1.

Though discredited as an anthropological term and not recommended in most editorial guidelines, it is still heard and used, for example, as a category on forms asking for ethnic identification. It is also still used for police blotters (the abbreviated Cauc may be heard among police) and appears elsewhere as a euphemism. Its synonym, Caucasoid, also once used in anthropology but now dated and considered pejorative, is disappearing.

- Mukhopadhyay, Carol C. (June 30, 2008). "Getting Rid of the Word 'Caucasian'". In Mica Pollock (ed.). Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real About Race in School. New Press. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-1-59558-567-7.

Yet there is one striking exception in our modern racial vocabulary: the term 'Caucasian'. Despite being a remnant of a discredited theory of racial classification, the term has persisted into the twenty-first century, within as well as outside of the educational community. It is high time we got rid of the word Caucasian. Some might protest that it is 'only a label'. But language is one of the most systematic, subtle, and significant vehicles for transmitting racial ideology. Terms that describe imagined groups, such as Caucasian, encapsulate those beliefs. Every time we use them and uncritically expose students to them, we are reinforcing rather than dismantling the old racialized worldview. Using the word Caucasian invokes scientific racism, the false idea that races are naturally occurring, biologically ranked subdivisions of the human species and that Caucasians are the superior race. Beyond this, the label Caucasian can even convey messages about which groups have culture and are entitled to recognition as Americans.

- Dewanjuly, Shaila (July 6, 2013). "Has 'Caucasian' Lost Its Meaning?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

AS a racial classification, the term Caucasian has many flaws, dating as it does from a time when the study of race was based on skull measurements and travel diaries ... Its equivalents from that era are obsolete – nobody refers to Asians as 'Mongolian' or blacks as 'Negroid'. ... There is no legal reason to use it. It rarely appears in federal statutes, and the Census Bureau has never put a checkbox by the word Caucasian. (White is an option.) ... The Supreme Court, which can be more colloquial, has used the term in only 64 cases, including a pair from the 1920s that reveal its limitations ... In 1889, the editors of the original Oxford English Dictionary noted that the term Caucasian had been 'practically discarded'. But they spoke too soon. Blumenbach's authority had given the word a pseudoscientific sheen that preserved its appeal. Even now, the word gives discussions of race a weird technocratic gravitas, as when the police insist that you step out of your 'vehicle' instead of your car ... Susan Glisson, who as the executive director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation in Oxford, Miss., regularly witnesses Southerners sorting through their racial vocabulary, said she rarely hears 'Caucasian'. 'Most of the folks who work in this field know that it's a completely ridiculous term to assign to whites,' she said. 'I think it's a term of last resort for people who are really uncomfortable talking about race. They use the term that's going to make them be as distant from it as possible.'

- ^ Baum 2006, p. 82.

- Figal 2010, pp. 81–84.

- Chardin, 1686, Journal du voyage du chevalier Chardin en Perse et aux Indes Orientales par la Mer Noire et par la Colchide, p.204, "Le sang de Géorgie est le plus beau d'Orient, et je puis dire du monde, je n'ai pas remarqué un laid visage en ce païs la, parmi l'un et l'autre sexe: mais j'y en ay vû d'Angeliques."

- For example, such as in the Allgemeine Erdbeschreibung published by Meyer in 1777: Allgemeine Erdbeschreibung: Asien - Volume 3. Meyer. 1777. p. 1435.

- Meiners, Christoph (1785). Grundriss der Geschichte der Menschheit. Im Verlage der Meyerschen Buchhandlung. pp. 25–.

- Luigi Marino, I Maestri della Germania (1975) OCLC 797567391; translated into German as Praeceptores Germaniae: Göttingen 1770–1820 OCLC 34194206

- B. Isaac, The invention of racism in classical antiquity, Princeton University Press, 2004, p. 105 OCLC 51942570

- Londa Schiebinger, The Anatomy of Difference: Race and Sex in Eighteenth-Century Science, Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 23, No. 4, Special Issue: The Politics of Difference, Summer, 1990, pp. 387–405

- B. Rupp-Eisenreich, "Des Choses Occultes en Histoire des Sciences Humaines: le Destin de la 'Science Nouvelle' de Christoph Meiners", L'Ethnographie v.2 (1983), p. 151

- F. Dougherty, "Christoph Meiners und Johann Friedrich Blumenbach im Streit um den Begriff der Menschenrasse," in G. Mann and F. Dumont, eds., Die Natur des Menschen , pp. 103–04

- Hochman, Leah (October 10, 2014). The Ugliness of Moses Mendelssohn: Aesthetics, Religion & Morality in the Eighteenth Century. Routledge. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-317-66997-5.

- Mikkelsen, Jon M. (August 1, 2013). Kant and the Concept of Race: Late Eighteenth-Century Writings. SUNY Press. pp. 196–. ISBN 978-1-4384-4363-8.

- Painter, N. "Why White People are Called Caucasian?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- Another online document reviews the early history of race theory.18th and 19th Century Views of Human Variation Archived October 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The treatises of Blumenbach can be found online here.

- The New American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge, Volume 4. Appleton. 1870. p. 588.

- ^ Bhopal R (December 2007). "The beautiful skull and Blumenbach's errors: the birth of the scientific concept of race". BMJ. 335 (7633): 1308–09. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.969.2221. doi:10.1136/bmj.39413.463958.80. PMC 2151154. PMID 18156242.

- Baum 2006, p. 88: "The connection between Meiners's ideas about a Caucasian branch of humanity and Blumenbach's later conception of a Caucasian variety (eventually, a Caucasian race) is not completely clear. What is clear is that the two editions of Meiners's Outline were published between the second edition of Blumenbach's On the Natural Variety of Mankind and the third edition, where Blumenbach first used the term Caucasian. Blumenbach cited Meiners once in 1795, but only to include Meiners's 1793 division of humanity into "handsome and white" and "ugly and dark" peoples among several alternative "divisions of the varieties of mankind." Yet Blumenbach must have been aware of Meiners's earlier designation of Caucasian and Mongolian branches of humanity, as the two men knew each other as colleagues at the University of Göttingen. The way that Blumenbach embraced the term Caucasian suggests that he worked to distance his own anthropological thinking from that of Meiners while recovering the term Caucasian for his own more refined racial classification: he made no mention of Meiners's 1785 usage and gave the term a new meaning.

- German: "sehr willkürlich": Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1797). Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. p. 61. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

Alle diese Verschiedenheiten fließen aber durch so mancherley Abstufungen und Uebergänge so unvermerkt zusammen, daß sich keine andre, als sehr willkürliche Grenzen zwischen ihnen festsetzen lassen.

- On the Natural Variety of Mankind, 3rd ed. (1795) in Bendyshe: 264–65; "racial face," 229.

- Freedman, B. J. (1984). "For debate... Caucasian". British Medical Journal. 288 (6418). Routledge: 696–98. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6418.696. PMC 1444385. PMID 6421437.

- ^ Coon, Carleton (April 1939). The Races of Europe. The Macmillan Company. p. 51.

- The Races of Europe, Chapter XIII, Section 2 Archived May 11, 2006, at archive.today

- ^ Jackson, J. P. Jr. (2001). ""In Ways Unacademical": The Reception of Carleton S. Coon's The Origin of Races". Journal of the History of Biology. 34 (2): 247–85. doi:10.1023/a:1010366015968. S2CID 86739986.

- The Origin of Races. Random House Inc., 1962, p. 570.

- Coon, Carleton Stevens (1939). The Races of Europe. The Macmillan Company. pp. 26–28, 50–55.

- Sachs Collopy, Peter (2015). "Race Relationships: Collegiality and Demarcation in Physical Anthropology". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 51 (3): 237–260. doi:10.1002/jhbs.21728. PMID 25950769.

- Spickard, Paul (2016). "The Return of Scientific Racism? DNA Ancestry Testing, Race, and the New Eugenics Movement". Race in Mind: Critical Essays. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 157. doi:10.2307/j.ctvpj76k0.11. ISBN 978-0-268-04148-9. JSTOR j.ctvpj76k0.11.

For more than four decades beginning in the late 1930s, the Harvard anthropologist Carleton Coon wrote a series of big books for an ever shrinking audience in which he pushed a pseudoscientific racial angle of analysis.

- Selcer, Perrin (2012). "Beyond the Cephalic Index: Negotiating Politics to Produce UNESCO's Scientific Statements on Race". Current Anthropology. 53 (S5): S180. doi:10.1086/662290. S2CID 146652143.

Most disturbingly for liberal anthropologists, the new generation of racist "pseudoscience" threatened to return to mainstream respectability in 1962 with the publication of Carleton Coon's The Origin of Races (Coon 1962).

- Loewen, James W. (2005). Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New York: New Press. p. 462. ISBN 9781565848870.

Carleton Coon, whose The Origin of Races claimed that Homo sapiens evolved five different times, blacks last. Its poor reception by anthropologists, followed by evidence from archaeology and paleontology that mankind evolved once, and in Africa, finally put an end to such pseudoscience.

- Regal, Brian (2011). "The Life of Grover Krantz". Searching for Sasquatch. Palgrave Studies in the History of Science and Technology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 93–94. doi:10.1057/9780230118294_5. ISBN 978-0-230-11829-4.

Carleton Coon fully embraced typology as a way to determine the basis of racial and ethnic difference Unfortunately for him, American anthropology increasingly equated typology with pseudoscience.

- Templeton, A. (2016). EVOLUTION AND NOTIONS OF HUMAN RACE. In Losos J. & Lenski R. (Eds.), How Evolution Shapes Our Lives: Essays on Biology and Society (pp. 346-361). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0s6j.26.

- "Miriam Claude Meijer, Race and Aesthetics in the Anthropology of Petrus Camper", 1722–1789, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999, pp. 169–74.

- Bertoletti, Stefano Fabbri. 1994. The anthropological theory of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. In Romanticism in science, science in Europe, 1790–1840.

- See individual literature for such Caucasoid identifications, while the following article gives a brief overview: How "Caucasoids" Got Such Big Crania and Why They Shrank: From Morton to Rushton, Leonard Lieberman, Current Anthropology, Vol. 42, No. 1, February 2001, pp. 69–95.

- "People and races", Alice Mossie Brues, Waveland Press, 1990, notes how the term Caucasoid replaced Caucasian.

- Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th edition, 1885–90, T11, p. 476.

- Wright, Arnold (1915). Southern India, Its History, People, Commerce, and Industrial Resources. Foreign and Colonial Compiling and Publishing Company. p. 69.

- Sharma, Ram Nath; Sharma, Rajendra K. (1997). Anthropology. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 109. ISBN 978-81-7156-673-0.

- Mhaiske, Vinod M.; Patil, Vinayak K.; Narkhede, S. S. (January 1, 2016). Forest Tribology And Anthropology. Scientific Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-93-86102-08-9.

- Simpson, George Eaton; Yinger, John Milton (1985). Racial and cultural minorities: an analysis of prejudice and discrimination, Environment, development, and public policy. Springer. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-306-41777-1.

- American anthropologist, American Anthropological Association, Anthropological Society of Washington (Washington, D.C.), 1984 v. 86, nos. 3–4, p. 741.

- T. H. Huxley, "On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind", Journal of the Ethnological Society of London (1870).

- Grolier Incorporated (2001) . Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 6. Grolier Incorporated. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7172-0134-1.

- Памиро-ферганская раса — article from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd edition).

- Wells, H. G. (1921). The outline of history, being a plain history of life and mankind. The Macmillan Company. pp. 119–123, 236–238. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- Carleton S. Coon, The Races of Europe (1930) Race and Racism: An Introduction (see also) by Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban, pp 127–133, December 8, 2005, ISBN 0759107955 Dmitry Bogatenkov; Stanislav Drobyshev. "Anthropology and Ethnic History" (in Russian). Peoples' Friendship University of Russia.

- Dmitry Bogatenkov; Stanislav Drobyshev. "Racial variety of Mankind, section 5.5.3" (in Russian). Peoples' Friendship University of Russia. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- School Bakai - Ethnogenesis the North Caucasus indigenous population

- Beals, Ralph L.; Hoijer, Harry (1953). An Introduction to Anthropology. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Listed according to: Nida, Eugene Albert (1954). Customs and Cultures: Anthropology for Christian Missions. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 283.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (2003). "Collective Degradation: Slavery and the Construction of Race. Why White People are Called Caucasian" (PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- Karen R. Humes; Nicholas A. Jones; Roberto R. Ramirez, eds. (March 2011). "Definition of Race Categories Used in the 2010 Census" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 3. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- Coulson, Doug (2015). "British Imperialism, the Indian Independence Movement, and the Racial Eligibility Provisions of the Naturalization Act: United States v. Thind Revisited". Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives. 7: 1–42. SSRN 2610266.

- "Not All Caucasians Are White: The Supreme Court Rejects Citizenship for Asian Indians", History Matters

- Tybaert, Sara; Rosov, Jane (November–December 2003). "MEDLINE Data Changes - 2004". NLM Technical Bulletin (335): e6.

The MeSH term Racial Stocks and its four children (Australoid Race, Caucasoid Race, Mongoloid Race, and Negroid Race) have been deleted from MeSH in 2004. A new heading, Continental Population Groups, has been created with new identification that emphasize geography.

Bibliography

- Camberg, Kim (December 13, 2005). "Long-term tensions behind Sydney riots". BBC News. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Figal, Sara Eigen (April 15, 2010). Heredity, Race, and the Birth of the Modern. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-89161-9.

- Leroi, Armand Marie (March 14, 2005). "A Family Tree in Every Gene". The New York Times. p. A23.

- Lewontin, Richard (2005). "Confusions About Human Races". Race and Genomics, Social Sciences Research Council. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (2003). "Collective Degradation: Slavery and the Construction of Race. Why White People are Called Caucasian" (PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Risch N, Burchard E, Ziv E, & Tang H (July 2002). "Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease". Genome Biol. 3 (7): comment2007.2001–12. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-comment2007. PMC 139378. PMID 12184798.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, et al. (December 2002). "Genetic structure of human populations". Science. 298 (5602): 2381–85. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.2381R. doi:10.1126/science.1078311. PMID 12493913. S2CID 8127224.

- Rosenberg NA, Mahajan S, Ramachandran S, Zhao C, Pritchard JK, & Feldman MW (December 2005). "Clines, Clusters, and the Effect of Study Design on the Inference of Human Population Structure". PLOS Genet. 1 (6): e70. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010070. PMC 1310579. PMID 16355252.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Templeton, Alan R. (September 1998). "Human races: A genetic and evolutionary perspective". American Anthropologist. 100 (3): 632–50. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.632. JSTOR 682042.

Literature

- Augstein, HF (1999). "From the Land of the Bible to the Caucasus and Beyond". In Harris, Bernard; Ernst, Waltraud (eds.). Race, Science and Medicine, 1700–1960. New York: Routledge. pp. 58–79. ISBN 978-0-415-18152-5.

- Baum, Bruce (2006). The rise and fall of the Caucasian race: a political history of racial identity. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9892-8.

- Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich (1775) On the Natural Varieties of Mankind – the book that introduced the concept

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (2000). Genes, Peoples and Languages. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9486-5.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The Mismeasure of Man. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01489-1. – a history of the pseudoscience of race, skull measurements, and IQ inheritability

- Guthrie, Paul (1999). The Making of the Whiteman: From the Original Man to the Whiteman. Chicago: Research Associates School Times. ISBN 978-0-948390-49-4.

- Piazza, Alberto; Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca & Menozzi, Paolo (1996). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02905-4. – a major reference of modern population genetics

- Stoddard, Theodore Lothrop (1924). Racial Realities in Europe. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Wolf, Eric R. & Cole, John N. (1999). The Hidden Frontier: Ecology and Ethnicity in an Alpine Valley. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21681-5.

| White people | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| European emigration by location |

| ||||||||||

| Historical concepts | |||||||||||

| Sociological phenomena and theories | |||||||||||

| Negative stereotypes of Whites | |||||||||||

| White identity politics | |||||||||||