Dots and boxes is a pencil-and-paper game for two players (sometimes more). It was first published in the 19th century by French mathematician Édouard Lucas, who called it la pipopipette. It has gone by many other names, including dots and dashes, game of dots, dot to dot grid, boxes, and pigs in a pen.

The game starts with an empty grid of dots. Usually two players take turns adding a single horizontal or vertical line between two unjoined adjacent dots. A player who completes the fourth side of a 1×1 box earns one point and takes another turn. A point is typically recorded by placing a mark that identifies the player in the box, such as an initial. The game ends when no more lines can be placed. The winner is the player with the most points. The board may be of any size grid. When short on time, or to learn the game, a 2×2 board (3×3 dots) is suitable. A 5×5 board, on the other hand, is good for experts.

Strategy

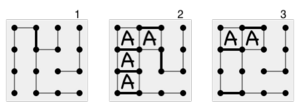

For most novice players, the game begins with a phase of more-or-less randomly connecting dots, where the only strategy is to avoid adding the third side to any box. This continues until all the remaining (potential) boxes are joined into chains – groups of one or more adjacent boxes in which any move gives all the boxes in the chain to the opponent. At this point, players typically take all available boxes, then open the smallest available chain to their opponent. For example, a novice player faced with a situation like position 1 in the diagram on the right, in which some boxes can be captured, may take all the boxes in the chain, resulting in position 2. But with their last move, they have to open the next, larger chain, and the novice loses the game.

A more experienced player faced with position 1 will instead play the double-cross strategy, taking all but 2 of the boxes in the chain and leaving position 3. The opponent will take these two boxes and then be forced to open the next chain. By achieving position 3, player A wins. The same double-cross strategy applies no matter how many long chains there are: a player using this strategy will take all but two boxes in each chain and take all the boxes in the last chain. If the chains are long enough, then this player will win.

The next level of strategic complexity, between experts who would both use the double-cross strategy (if they were allowed to), is a battle for control: an expert player tries to force their opponent to open the first long chain, because the player who first opens a long chain usually loses. Against a player who does not understand the concept of a sacrifice, the expert simply has to make the correct number of sacrifices to encourage the opponent to hand them the first chain long enough to ensure a win. If the other player also sacrifices, the expert has to additionally manipulate the number of available sacrifices through earlier play.

In combinatorial game theory, Dots and Boxes is an impartial game and many positions can be analyzed using Sprague–Grundy theory. However, Dots and Boxes lacks the normal play convention of most impartial games (where the last player to move wins), which complicates the analysis considerably.

Unusual grids and variants

Dots and Boxes need not be played on a rectangular grid – it can be played on a triangular grid or a hexagonal grid.

Dots and boxes has a dual graph form called "Strings-and-Coins". This game is played on a network of coins (vertices) joined by strings (edges). Players take turns cutting a string. When a cut leaves a coin with no strings, the player "pockets" the coin and takes another turn. The winner is the player who pockets the most coins. Strings-and-Coins can be played on an arbitrary graph.

In analyses of Dots and Boxes, a game that starts with outer lines already drawn is called a Swedish board while the standard version that starts fully blank is called an American board. An intermediate version with only the left and bottom sides starting with drawn lines is called an Icelandic board.

A related game is Dots, played by adding coloured dots to a blank grid, and joining them with straight or diagonal line in an attempt to surround an opponent's dots.

References

- Lucas, Édouard (1895), "La Pipopipette: nouveau jeu de combinaisons", L'arithmétique amusante, Paris: Gauthier-Villars et fils, pp. 204–209.

- ^ Berlekamp, Elwyn R.; Conway, John H.; Guy, Richard K. (1982), "Chapter 16: Dots-and-Boxes", Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays, Volume 2: Games in Particular, Academic Press, pp. 507–550.

- Holladay, J. C. (1966), "A note on the game of dots", American Mathematical Monthly, 73 (7): 717–720, doi:10.2307/2313978, JSTOR 2313978, MR 0200068.

- Swain, Heather (2012), Play These Games: 101 Delightful Diversions Using Everyday Items, Penguin, pp. 160–162, ISBN 9781101585030.

- Solomon, Eric (1993), "Boxes: an enclosing game", Games with Pencil and Paper, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 37–39, ISBN 9780486278728. Reprint of 1973 publication by Thomas Nelson and Sons.

- King, David C. (1999), Civil War Days: Discover the Past with Exciting Projects, Games, Activities, and Recipes, American Kids in History, vol. 4, Wiley, pp. 29–30, ISBN 9780471246121.

- Berlekamp, Elwyn (2000), The Dots-and-Boxes Game: Sophisticated Child's Play, AK Peters, Ltd, ISBN 1-56881-129-2.

- Berlekamp, Conway & Guy (1982), "the 4-box game", pp. 513–514.

- Berlekamp (2000), p. xi: "is big enough to be quite challenging, and yet small enough to keep the game reasonably short".

- ^ West, Julian (1996), "Championship-level play of dots-and-boxes" (PDF), in Nowakowski, Richard (ed.), Games of No Chance, Berkeley: MSRI Publications, pp. 79–84.

- Wilson, David, Dots-and-Boxes Analysis Results, University of Wisconsin, retrieved 2016-04-07.

External links

- Barile, Margherita, "Dots and Boxes", MathWorld