This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Modern circular chess Modern circular chess | |

| Years active | 10th century AD to present |

|---|---|

| Genres | Abstract strategy game Chess variant |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | ~1 minute |

| Playing time | May vary from 10 minutes (informal or Blitz games) to several hours (tournament) |

| Chance | None |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

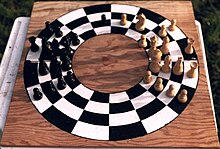

Circular chess is a chess variant played using the standard set of pieces on a circular board consisting of four rings, each of sixteen squares. This is topologically equivalent to playing on the curved surface of a cylinder.

History

The Chronicles of nearly a thousand years of "The Persians, Arabs, Byzantines and other people who were playing chess does have described various forms, movements, rules that have given them to the game and their peculiarities and placing the pieces in a circular board... ". In fact, documents in the British Library and elsewhere suggest that circular chess was played in Persia as early as the 10th century AD, and further references are found in India, Persia.

The great Arab scholar of origin Yemeni Ibnal-Khatibis who documented the creation of the chess circle, found in a manuscript 618 in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, describing a round chess circular called Rumi, a chess tournament Arabstyle, published in Al-Andalus and is also attributed to Abu Ali Ibn al-Murci Rashiq (died in 694), the invention of a chess move, documented by historian and scholar Ibn Al-Jatiba who leaves testimony Circular Chess. Everything indicates that chess move is of Persian origin and Arabic and then adopted and played by the Byzantine Empire.

Historical rules are in sources that are little-known in the West, such as Muhammad ibn Mahmud Amuli's 'Treasury of the Sciences', so when, in 1983, Lincoln historian David Reynolds came across a reference to the game being played in the Middle Ages and set about attempting to revive interest in it, he chose to draw up a new set of rules, based around those of orthodox chess. Since that time, the older rules of circular chess have become far better known. Abu Faisal Sergio Tapia, international and geopolitical analyst and expert over Middle East in various media of the Arab and Islamic world, who notes that Circular Chess - in all its beauty, in all its game-style it is the art of placing the parts in strategic positions from the start on two fronts, and expresses the true sense of the Persians and Arabs of the time chess. It is a circular board where the rings represent the universal knowledge, God, faith, creation, harmony of tactics, the ancient wisdom, the DNA of chess in the history of mankind. And likewise the Islamic style abstract pieces are the oldest chronologically in chess. The Circular Chess known as "al-Muddawara", "ar Rumiya" or "the Byzantine chess".

Historical circular chess

Rules

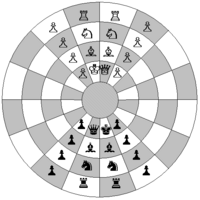

One set of rules for medieval circular chess is from the Persian author Muhammad ibn Mahmud Amuli's 'Treasury of the Sciences' (1325). In this version, called shatranj al-muddawara (circular chess) or shatranj ar-Rūmīya (Roman or Byzantine chess), the game uses a board with four concentric rings, each split into 16 spaces. The Board contains 64 squares. With an algebraic notation in the round board, in letters of 4 rings ABCD and every space with a number from 1 to 16. A game of chess is played between two players; each has 16 pieces, white, and black opponents of calls. The purpose of Circular Chess is to position their chess pieces in order to checkmate the opponent's king, ending the game.

The game uses the same pieces as shatranj. The king and the counselor on the inner ring, next to each other. The next ring has the elephants, the next ring has the knights, and the last ring has the rooks. A single row of 4 pawns flanks each side of the central pieces. The king of one side "faces" the counselor of the other (a shorter path is between the king of one side and the counselor of the other than between the kings of the two sides). Movement is the same as shatranj, except that, if two pawns from the same side, going in opposite directions, end up being blocked by each other, the opponent may remove both pieces, which does not use the opponent's turn. As there is no back row, there is no promotion. A stalemate is a victory for the stalemating player. A bare king is a loss for the player who only has the king left unless, in the next turn, the player can also impose a bare king, at which point the game is a draw.

Citadel chess

A variant of this game attested by Muhammad ibn Mahmud Amuli has two "citadel" spaces in the centre of the board and a different starting setup. In the citadel game, if a king reaches the citadel, a draw is forced.

Modern circular chess

Rules

The starting position is essentially obtained from that of orthodox chess by cutting the board in half and bending the two halves to join at the ends. Two lines are marked on opposite sides of the board, and each set of pieces is positioned so as to straddle this line. The king and queen start on the innermost ring, with, as is the case in square chess, the queen on a square of the same colour; the bishops start in the second ring from the centre, the knights on the third and the rooks on the outermost ring. The pawns are positioned in front of the pieces.

The moves of the pieces are identical to those in orthodox chess; a queen or rook may, if it is not obstructed, move any distance round a ring, except that the "null move" of moving a piece all the way round the board and back to its original square is not permitted. A pawn is promoted after moving six squares from its initial position, to the square immediately before the opponent's starting line. Castling and en passant captures are not permitted. Announcing a check is not obligatory, and "snaffling" (winning the game immediately by capturing the opponent's king after he either moved into or failed to move out of check) is allowed – and has on more than one occasion decided a world championship game.

Theory

Orthodox chess generally assigns the pieces relative values of 9 points for a queen, 5 for a rook, 3 for a bishop or knight, and 1 for a pawn; although no attempt has been made to assign specific values for circular chess, it is certain that the same values do not hold. The values of the queen and rook are considerably augmented by their greater range – with two rooks or a queen and rook unobstructed on the same ring being especially powerful – while those of the bishop and knight are diminished; for example, on an 8×8 board two minor pieces are held to be stronger than one rook, but on a circular board the rook is considerably stronger. This can be easily seen by just counting the number of squares an unobstructed piece is able to attack on an orthodox and a circular board: the queen, rook, bishop, and knight can attack 27, 14, 13, and 8 squares respectively on an orthodox board, while on a circular board the counts are instead 24, 18, 6, and 6. The minor pieces can, however, pose a significant danger value, as their moves are more difficult to visualise on the circular board and even strong players often fail to notice a threat.

One of the major differences between orthodox and circular chess in practice is in the opening. In orthodox chess, opening theory has developed over several centuries, and the use of computer analysis has resulted in top level games frequently not deviating from known theory until the 20th move or beyond; in circular chess, there is virtually no opening theory, and consequently players are "on their own" from the first move. In orthodox chess, advancing the king's or queen's pawn are generally considered the best opening moves, as doing so attacks two key central squares, opens a diagonal to enable the development of a bishop, and, in the case of the king's pawn, the queen also. On a circular board these advantages are negated, as a king's or queen's pawn only attacks one square, and its advance only opens one square for the bishop. Some players advance the central pawns first anyway, while others prefer to advance the rooks' pawns in order to open lines of attack for the more powerful pieces; it is not known which move, if any, is objectively best.

The different geometry of the square and circular boards creates considerable differences in endgame theory: three of the four "basic checkmates" on a square board (those with king and rook, king and two bishops, or king and bishop and knight against a lone king) rely on forcing the defending king into the corner of the board, and thus are impossible on a circular board since it doesn't have corners. The "basic mates" in circular chess are thus those with king and queen, king and rook and minor piece, or king and three minor pieces against a lone king. The greater tendency towards drawn endgames often results in the defender playing on in a position which would be considered cause for resignation on a square board. In one particular endgame, however, the circular board favours the attacker: with king and pawn against king, there is no stalemate defence (since it is impossible for the king to be trapped against a side of the board that the pawn is moving towards) and thus the only way for the defending king to draw is to capture the pawn before it can be either defended or promoted (otherwise the endgame is always a win).

World Championship

After experimenting with various possible layouts for the game, Reynolds decided on that pictured above, constructed a board and introduced the game to other players in Lincoln; it caught on, and in 1996, the Circular Chess Society was formed, with the aim of popularising circular chess, primarily by organising a tournament. Since it was not known to be played competitively anywhere else, its claim to the status of world championship was not contested, and thus it became. The inaugural tournament was held in the Tap and Spile public house in Lincoln in 1996; it was played as a knockout, with Lincoln player Rob Stevens beating Nottinghamshire's Mark Spink in the final. Subsequently, the tournament has been held at different venues in Lincoln, usually under the Swiss system, and has been dominated by two players: Peterborough engineer Francis Bowers and Dutch businessman Herman Kok, who between them won eight of the following ten tournaments. Bowers took the title from 1997 to 1999, and remains not just the only player to have won the tournament three years in succession, but the only one to win on more than two occasions; Kok broke the sequence with victory in the 2000 tournament, before Bowers won again in 2001.

The 2002 World Championship, staged in Bishop Edward King House in Lincoln and sponsored by the Duke William Hotel, saw the only instance to date of the participation in the tournament of a player widely known outside the world of circular chess: David Howell, then aged 11 and having recently gained national publicity by becoming the youngest player to avoid defeat (at standard chess) against a reigning world champion, with a draw in the final game of his match against Vladimir Kramnik (having lost the other three games). Howell won the tournament, scoring a maximum 5 points after beating Bowers in the final round, although he commented afterwards "This is the first time I have played in a circular chess contest and it was difficult. Circular chess is a lot harder to play than square chess. Every time you or your opponent makes a move, you have to think about what is happening on the other side of the board." Kok finished runner-up with 4+1⁄2 points.

The 2003 tournament was again held in Bishop Edward King House; sponsorship for it and the four subsequent tournaments came from Lindum Group. Howell did not return to defend his title (and has not played in the tournament since); Bowers gained his fifth title with victory over Kok in the last round to complete a 5/5 score, and Lincolnshire player David Carew, with 4+1⁄2, finished second. Bowers repeated the feat the following year, again finishing with a win against Kok; Nottinghamshire's Mike Clark was the runner-up, with Stevens third and Kok and Carew among a group of six players in joint fourth place.

In 2005, the Society gained extra publicity for the tournament by securing the chapter house of Lincoln Cathedral as the venue, only the day after the filming of The Da Vinci Code there had been completed (the cathedral was used to film scenes which, in the book, take place in Westminster Abbey, since the abbey had refused Columbia Pictures permission to film there); much of the film set was (and is) still in place. The draw for the first round of the tournament was conducted by Councillor Steve Allnutt, the Deputy Mayor of Lincoln, and Mrs Chris Noble, the City Sheriff; the two guests accepted an invitation to try the game for themselves, with the Sheriff emerging as the winner. In contrast to previous tournaments, the 2005 championship was held over four rounds rather than five; in the first Stevens drew with Bowers, to end the latter's run of ten consecutive wins in the tournament and leave Kok the favourite to take the title again. At the halfway point there were four players with maximum points – Kok, Hertfordshire's John Beasley, and tournament newcomers David Stamp and Michael Jones, both of Lincolnshire – with Bowers on 1+1⁄2 after surviving a scare to "snaffle" Carew in the second round. Kok beat Beasley in the third round, while Stamp and Jones remained in contention after both winning; Bowers also won, although, since the top four players would be drawn against each other in the final round, his chances of retaining his title were remote, relying on him winning his own game and the other being drawn to force a three-way playoff. The draw for the final round pitted Kok against Jones and Bowers against Stamp – in each case an experienced player against a tournament newcomer. The former game looked to be heading in Kok's favour before he blundered in time trouble and eventually lost on time, leaving Jones on 4/4 and Stamp needing to beat Bowers to force a tiebreak; he could only draw, so Jones finished the outright champion and Stamp runner-up with 31⁄2. Bowers, Herman Kok, his son Robbie, Beasley and Clark tied for third place with 3 points each.

The 2006 World Championship was held at Lincoln Castle, and was dedicated to regular competitor Charles Vermes of Derbyshire, who had died shortly before. The first round brought no surprise results – the only two of the main contenders to be drawn together were Clark and Stevens, with Clark emerging the winner; Jones, Herman Kok and Bowers all won. Clark beat Jones in the second round, at which point there remained five players on maximum points: Clark, Kok, Bowers, Lincolnshire's Richard Kidals and Ian Lewis of Cardiff. Lewis lost his third-round game to tournament founder Reynolds, but the other four leaders all won, ensuring the need for a tiebreak unless one of the last round games was drawn; Kok beat Clark and Bowers beat Kidals to give them both the maximum 4 points, so the expected tiebreak game ensued. The game was close throughout, with Bowers eventually losing on time to give Kok the title – only the second player, after Bowers himself, to claim it more than once.

The 2007 World Championship was held at The Tap & Spile in Lincoln, with Kevin McCarthy lifting the title after remaining unbeaten in his first ever tournament under Circular Rules, including a win against the legendary Herman Kok, who had taught him the rules only a fortnight previously.

The 2011 World Championship was also held at The Tap & Spile in Lincoln, with newcomer Nigel Payne, previously a Welsh All Valleys Champion (Under-15 category), claiming the title.

See also

- Six-player circular chess – a circular variant for multiple players by Hridayeshwar Singh Bhati

References

- Gollon, John (1969). Chess variations: Ancient, Regional and Modern. Tuttle Pub. p. 223. ISBN 978-0804811224.

External links

- The Circular Chess Society

- Historical roots

- Circular Chess Handbook by Abu Faisal Tapia

- "Circular Chess" by Hans Bodlaender, The Chess Variant Pages

- Circular Chess at BoardGameGeek

- Circular Chess Software (Windows 95 – Windows 7)

- Circular Chess Software (Windows 3.x)

- An Open Source Online Circular Chess

- Circular Chess a simple program by Ed Friedlander (Java)

- Circular Chess Board Painter a freeware program editing Circular Chess Boards with Classic Chess pieces but also with fairy Chess pieces.

| Chess variants (list) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodox rules |

| ||||||||

| Unorthodox rules with traditional pieces |

| ||||||||

| Unorthodox rules using non-traditional pieces |

| ||||||||

| Multiplayer | |||||||||

| Inspired games | |||||||||

| Chess-related games |

| ||||||||

| Software | |||||||||

| Related | |||||||||