| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

| Models of the nucleus |

Nuclides' classification

|

| Nuclear stability |

| Radioactive decay |

| Nuclear fission |

| Capturing processes |

| High-energy processes |

|

Nucleosynthesis and nuclear astrophysics

|

| High-energy nuclear physics |

| Scientists |

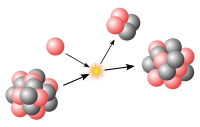

Alpha decay or α-decay is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits an alpha particle (helium nucleus) and thereby transforms or "decays" into a different atomic nucleus, with a mass number that is reduced by four and an atomic number that is reduced by two. An alpha particle is identical to the nucleus of a helium-4 atom, which consists of two protons and two neutrons. It has a charge of +2 e and a mass of 4 Da. For example, uranium-238 decays to form thorium-234.

While alpha particles have a charge +2 e, this is not usually shown because a nuclear equation describes a nuclear reaction without considering the electrons – a convention that does not imply that the nuclei necessarily occur in neutral atoms.

Alpha decay typically occurs in the heaviest nuclides. Theoretically, it can occur only in nuclei somewhat heavier than nickel (element 28), where the overall binding energy per nucleon is no longer a maximum and the nuclides are therefore unstable toward spontaneous fission-type processes. In practice, this mode of decay has only been observed in nuclides considerably heavier than nickel, with the lightest known alpha emitter being the second lightest isotope of antimony, Sb. Exceptionally, however, beryllium-8 decays to two alpha particles.

Alpha decay is by far the most common form of cluster decay, where the parent atom ejects a defined daughter collection of nucleons, leaving another defined product behind. It is the most common form because of the combined extremely high nuclear binding energy and relatively small mass of the alpha particle. Like other cluster decays, alpha decay is fundamentally a quantum tunneling process. Unlike beta decay, it is governed by the interplay between both the strong nuclear force and the electromagnetic force.

Alpha particles have a typical kinetic energy of 5 MeV (or ≈ 0.13% of their total energy, 110 TJ/kg) and have a speed of about 15,000,000 m/s, or 5% of the speed of light. There is surprisingly small variation around this energy, due to the strong dependence of the half-life of this process on the energy produced. Because of their relatively large mass, the electric charge of +2 e and relatively low velocity, alpha particles are very likely to interact with other atoms and lose their energy, and their forward motion can be stopped by a few centimeters of air.

Approximately 99% of the helium produced on Earth is the result of the alpha decay of underground deposits of minerals containing uranium or thorium. The helium is brought to the surface as a by-product of natural gas production.

History

See also: Alpha particle § History of discovery and useAlpha particles were first described in the investigations of radioactivity by Ernest Rutherford in 1899, and by 1907 they were identified as He ions. By 1928, George Gamow had solved the theory of alpha decay via tunneling. The alpha particle is trapped inside the nucleus by an attractive nuclear potential well and a repulsive electromagnetic potential barrier. Classically, it is forbidden to escape, but according to the (then) newly discovered principles of quantum mechanics, it has a tiny (but non-zero) probability of "tunneling" through the barrier and appearing on the other side to escape the nucleus. Gamow solved a model potential for the nucleus and derived, from first principles, a relationship between the half-life of the decay, and the energy of the emission, which had been previously discovered empirically and was known as the Geiger–Nuttall law.

Mechanism

The nuclear force holding an atomic nucleus together is very strong, in general much stronger than the repulsive electromagnetic forces between the protons. However, the nuclear force is also short-range, dropping quickly in strength beyond about 3 femtometers, while the electromagnetic force has an unlimited range. The strength of the attractive nuclear force keeping a nucleus together is thus proportional to the number of the nucleons, but the total disruptive electromagnetic force of proton-proton repulsion trying to break the nucleus apart is roughly proportional to the square of its atomic number. A nucleus with 210 or more nucleons is so large that the strong nuclear force holding it together can just barely counterbalance the electromagnetic repulsion between the protons it contains. Alpha decay occurs in such nuclei as a means of increasing stability by reducing size.

One curiosity is why alpha particles, helium nuclei, should be preferentially emitted as opposed to other particles like a single proton or neutron or other atomic nuclei. Part of the reason is the high binding energy of the alpha particle, which means that its mass is less than the sum of the masses of two free protons and two free neutrons. This increases the disintegration energy. Computing the total disintegration energy given by the equation where mi is the initial mass of the nucleus, mf is the mass of the nucleus after particle emission, and mp is the mass of the emitted (alpha-)particle, one finds that in certain cases it is positive and so alpha particle emission is possible, whereas other decay modes would require energy to be added. For example, performing the calculation for uranium-232 shows that alpha particle emission releases 5.4 MeV of energy, while a single proton emission would require 6.1 MeV. Most of the disintegration energy becomes the kinetic energy of the alpha particle, although to fulfill conservation of momentum, part of the energy goes to the recoil of the nucleus itself (see atomic recoil). However, since the mass numbers of most alpha-emitting radioisotopes exceed 210, far greater than the mass number of the alpha particle (4), the fraction of the energy going to the recoil of the nucleus is generally quite small, less than 2%. Nevertheless, the recoil energy (on the scale of keV) is still much larger than the strength of chemical bonds (on the scale of eV), so the daughter nuclide will break away from the chemical environment the parent was in. The energies and ratios of the alpha particles can be used to identify the radioactive parent via alpha spectrometry.

These disintegration energies, however, are substantially smaller than the repulsive potential barrier created by the interplay between the strong nuclear and the electromagnetic force, which prevents the alpha particle from escaping. The energy needed to bring an alpha particle from infinity to a point near the nucleus just outside the range of the nuclear force's influence is generally in the range of about 25 MeV. An alpha particle within the nucleus can be thought of as being inside a potential barrier whose walls are 25 MeV above the potential at infinity. However, decay alpha particles only have energies of around 4 to 9 MeV above the potential at infinity, far less than the energy needed to overcome the barrier and escape.

Quantum tunneling

Quantum mechanics, however, allows the alpha particle to escape via quantum tunneling. The quantum tunneling theory of alpha decay, independently developed by George Gamow and by Ronald Wilfred Gurney and Edward Condon in 1928, was hailed as a very striking confirmation of quantum theory. Essentially, the alpha particle escapes from the nucleus not by acquiring enough energy to pass over the wall confining it, but by tunneling through the wall. Gurney and Condon made the following observation in their paper on it:

It has hitherto been necessary to postulate some special arbitrary 'instability' of the nucleus, but in the following note, it is pointed out that disintegration is a natural consequence of the laws of quantum mechanics without any special hypothesis... Much has been written of the explosive violence with which the α-particle is hurled from its place in the nucleus. But from the process pictured above, one would rather say that the α-particle almost slips away unnoticed.

The theory supposes that the alpha particle can be considered an independent particle within a nucleus, that is in constant motion but held within the nucleus by strong interaction. At each collision with the repulsive potential barrier of the electromagnetic force, there is a small non-zero probability that it will tunnel its way out. An alpha particle with a speed of 1.5×10 m/s within a nuclear diameter of approximately 10 m will collide with the barrier more than 10 times per second. However, if the probability of escape at each collision is very small, the half-life of the radioisotope will be very long, since it is the time required for the total probability of escape to reach 50%. As an extreme example, the half-life of the isotope bismuth-209 is 2.01×10 years.

The isotopes in beta-decay stable isobars that are also stable with regards to double beta decay with mass number A = 5, A = 8, 143 ≤ A ≤ 155, 160 ≤ A ≤ 162, and A ≥ 165 are theorized to undergo alpha decay. All other mass numbers (isobars) have exactly one theoretically stable nuclide. Those with mass 5 decay to helium-4 and a proton or a neutron, and those with mass 8 decay to two helium-4 nuclei; their half-lives (helium-5, lithium-5, and beryllium-8) are very short, unlike the half-lives for all other such nuclides with A ≤ 209, which are very long. (Such nuclides with A ≤ 209 are primordial nuclides except Sm.)

Working out the details of the theory leads to an equation relating the half-life of a radioisotope to the decay energy of its alpha particles, a theoretical derivation of the empirical Geiger–Nuttall law.

Uses

Americium-241, an alpha emitter, is used in smoke detectors. The alpha particles ionize air in an open ion chamber and a small current flows through the ionized air. Smoke particles from the fire that enter the chamber reduce the current, triggering the smoke detector's alarm.

Radium-223 is also an alpha emitter. It is used in the treatment of skeletal metastases (cancers in the bones).

Alpha decay can provide a safe power source for radioisotope thermoelectric generators used for space probes and were used for artificial heart pacemakers. Alpha decay is much more easily shielded against than other forms of radioactive decay.

Static eliminators typically use polonium-210, an alpha emitter, to ionize the air, allowing the "static cling" to dissipate more rapidly.

Toxicity

Highly charged and heavy, alpha particles lose their several MeV of energy within a small volume of material, along with a very short mean free path. This increases the chance of double-strand breaks to the DNA in cases of internal contamination, when ingested, inhaled, injected or introduced through the skin. Otherwise, touching an alpha source is typically not harmful, as alpha particles are effectively shielded by a few centimeters of air, a piece of paper, or the thin layer of dead skin cells that make up the epidermis; however, many alpha sources are also accompanied by beta-emitting radio daughters, and both are often accompanied by gamma photon emission.

Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) quantifies the ability of radiation to cause certain biological effects, notably either cancer or cell-death, for equivalent radiation exposure. Alpha radiation has a high linear energy transfer (LET) coefficient, which is about one ionization of a molecule/atom for every angstrom of travel by the alpha particle. The RBE has been set at the value of 20 for alpha radiation by various government regulations. The RBE is set at 10 for neutron irradiation, and at 1 for beta radiation and ionizing photons.

However, the recoil of the parent nucleus (alpha recoil) gives it a significant amount of energy, which also causes ionization damage (see ionizing radiation). This energy is roughly the weight of the alpha (4 Da) divided by the weight of the parent (typically about 200 Da) times the total energy of the alpha. By some estimates, this might account for most of the internal radiation damage, as the recoil nucleus is part of an atom that is much larger than an alpha particle, and causes a very dense trail of ionization; the atom is typically a heavy metal, which preferentially collect on the chromosomes. In some studies, this has resulted in an RBE approaching 1,000 instead of the value used in governmental regulations.

The largest natural contributor to public radiation dose is radon, a naturally occurring, radioactive gas found in soil and rock. If the gas is inhaled, some of the radon particles may attach to the inner lining of the lung. These particles continue to decay, emitting alpha particles, which can damage cells in the lung tissue. The death of Marie Curie at age 66 from aplastic anemia was probably caused by prolonged exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation, but it is not clear if this was due to alpha radiation or X-rays. Curie worked extensively with radium, which decays into radon, along with other radioactive materials that emit beta and gamma rays. However, Curie also worked with unshielded X-ray tubes during World War I, and analysis of her skeleton during a reburial showed a relatively low level of radioisotope burden.

The Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko's 2006 murder by radiation poisoning is thought to have been carried out with polonium-210, an alpha emitter.

References

- F.G. Kondev et al 2021 Chinese Phys. C 45 030001

- "Gamow theory of alpha decay". 6 November 1996. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009.

- ^ Arthur Beiser (2003). "Chapter 12: Nuclear Transformations". Concepts of Modern Physics (PDF) (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 432–434. ISBN 0-07-244848-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- G. Gamow (1928). "Zur Quantentheorie des Atomkernes (On the quantum theory of the atomic nucleus)". Zeitschrift für Physik. 51 (3): 204–212. Bibcode:1928ZPhy...51..204G. doi:10.1007/BF01343196. S2CID 120684789.

- ^ Ronald W. Gurney & Edw. U. Condon (1928). "Wave Mechanics and Radioactive Disintegration". Nature. 122 (3073): 439. Bibcode:1928Natur.122..439G. doi:10.1038/122439a0.

- Belli, P.; Bernabei, R.; Danevich, F. A.; et al. (2019). "Experimental searches for rare alpha and beta decays". European Physical Journal A. 55 (8): 140–1–140–7. arXiv:1908.11458. Bibcode:2019EPJA...55..140B. doi:10.1140/epja/i2019-12823-2. ISSN 1434-601X. S2CID 201664098.

- "Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator". Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Nuclear-Powered Cardiac Pacemakers". Off-Site Source Recovery Project. LANL. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Winters TH, Franza JR (1982). "Radioactivity in Cigarette Smoke". New England Journal of Medicine. 306 (6): 364–365. doi:10.1056/NEJM198202113060613. PMID 7054712.

- "ANS: Public Information: Resources: Radiation Dose Chart". Archived from the original on 2018-07-15. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- EPA Radiation Information: Radon. October 6, 2006, Archived 2006-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed December 6, 2006,

- Health Physics Society, "Did Marie Curie die of a radiation overexposure?" Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

Notes

- These other decay modes, while possible, are extremely rare compared to alpha decay.

External links

The LIVEChart of Nuclides - IAEA with filter on alpha decay

The LIVEChart of Nuclides - IAEA with filter on alpha decay- Alpha decay with 3 animated examples showing the recoil of daughter

See also

| Nuclear processes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioactive decay | |||||

| Stellar nucleosynthesis | |||||

| Other processes |

| ||||

where mi is the initial mass of the nucleus, mf is the mass of the nucleus after particle emission, and mp is the mass of the emitted (alpha-)particle, one finds that in certain cases it is positive and so alpha particle emission is possible, whereas other decay modes would require energy to be added. For example, performing the calculation for

where mi is the initial mass of the nucleus, mf is the mass of the nucleus after particle emission, and mp is the mass of the emitted (alpha-)particle, one finds that in certain cases it is positive and so alpha particle emission is possible, whereas other decay modes would require energy to be added. For example, performing the calculation for