This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Giovanni Giove (talk | contribs) at 10:08, 15 November 2006 (→Was Polo Croat?). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:08, 15 November 2006 by Giovanni Giove (talk | contribs) (→Was Polo Croat?)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- This article is about the Venetian explorer. For other uses, see Marco Polo (disambiguation)

| Marco Polo |

|---|

Marco Polo (September 15 1254 – January 8 1324) was a Venetian trader and explorer (presumably of noble origins from Sebenico and Curzola in Dalmatia) who, together with his father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo, was one of the first Westerners to travel the Silk Road to China (which he called Cathay) and visited the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, Kublai Khan (grandson of Genghis Khan). His travels are written down in Il Milione ("The Million" or The Travels of Marco Polo).

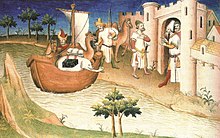

The voyage of Niccolò and Maffeo Polo

The Polo name originally did not belong to a family of explorers, but to a family of traders. Marco Polo's father, Niccolò (also Nicolò in Venetian) and his uncle, Maffeo (also Maffio), were prosperous merchants who traded with the East. They were partners with a third brother, named Marco il vecchio (the Elder).

In 1259, the two brothers lived in the Venetian quarter of Constantinople, where they enjoyed political privileges and tax relief because of their country’s role in establishing the Latin Empire in the Fourth Crusade of 1204. But the family judged the political situation of the city precarious, so they decided to transfer their business northeast to Soldaia, a city in Crimea. Their decision proved wise. Constantinople was recaptured in 1261 by Michael Palaeologus, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, who promptly burned the Venetian quarter. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded, while many of those who managed to escape perished aboard overloaded refugee ships fleeing to other Venetian colonies in the Aegean Sea.

As their new home on the north rim of the Black Sea, Soldaia had been frequented by Venetian traders since the 12th century. The Mongol army sacked it in 1223, but the city had never been definitively conquered until 1239, when it became a part of the newly formed Mongol state known as the Golden Horde. Searching for better profits, the Polos continued their journey to Sarai, where the court of Berke Khan, the ruler of the Golden Horde, was located. At that time, the city of Sarai — already visited by William of Rubruck a few years earlier — was no more than a huge encampment, and the Polos stayed for about a year. Finally, they decided to avoid Crimea, because of a civil war between Berke and his cousin Hulagu or perhaps because of the bad relationship between Berke Khan and the Byzantine Empire. Instead, they moved further east to Bukhara, in modern day Uzbekistan, where the family lived and traded for three years.

In 1264, Nicolò and Maffio joined up with an embassy sent by the Ilkhan Hulagu to his brother, the Grand Khan Kublai. In 1266, they reached the seat of the Grand Khan in the Mongol capital Khanbaliq, now known as Beijing, China.

In his book, Il Milione, Marco explains how Kublai officially received the Polos and sent them back — with a Mongol named Koeketei as an ambassador to the Pope. They brought with them a letter from the Khan requesting educated people to come and teach Christianity and Western customs to his people, as well as the paiza, a golden tablet a foot long and three inches wide, authorizing the holder to require and obtain lodging, horses and food throughout the Great Khan's dominion. Koeketei left in the middle of the journey, leaving the Polos to travel alone to Ayas in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. From that port city, they sailed to Saint Jean d'Acre, capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The long sede vacante — between the death of Pope Clement IV, in 1268, and the election of Pope Gregory X, in 1271 — prevented the Polos from fulfilling Kublai’s request. As suggested by Theobald Visconti, papal legate for the realm of Egypt, in Acres for the Ninth Crusade, the two brothers returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270, waiting for the nomination of the new Pope.

The voyages of Marco

The journey to Cathay

Maffeo and Niccolò Polo set out on a second journey with the Pope's response to Kublai Khan, in 1271. This time Niccolò took his son Marco, along with two friars that did not finish the voyage due to fear.

The service to the Khan

When Marco Polo arrived at Kublai Khan's court he became a favorite of the Khan and was employed for 17 years and was sent on voyages and was given permission to trade freely throughout China

The return to Europe

In 1291, Kublai entrusted Marco with his last duty, to escort the Mongol princess Koekecin (Cocacin in Il Milione) to her betrothed, the Ilkhan Arghun. In 1293 or 1294 the Polos reached the Ilkhanate, ruled by Gaykhatu after the death of Arghun, and left Koekecin with the new Ilkhan. Then they moved to Trabzon and from that city sailed to Venice.

Il Milione

- See also: The Travels of Marco Polo

On their return from China in 1295, the family settled in Venice where they became a sensation and attracted crowds of listeners who had difficulties in believing their reports of distant China. According to a late tradition, since they did not believe him, Marco Polo invited them all to dinner one night during which the Polos dressed in the simple clothes of a peasant in China. Shortly before the crowds ate, the Polos opened their pockets to reveal hundreds of rubies and other jewels which they had received in Asia. Though they were much impressed, the people of Venice still doubted the Polos.

Marco Polo was later captured in a minor clash of the war between Venice and Genoa, or in the naval battle of Curzola, according to a dubious tradition. He spent the few months of his imprisonment, in 1298, dictating to a fellow prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa, a detailed account of his travels in the then-unknown parts of the Far East.

His book, Il Milione (the title comes from either "The Million", then considered a gigantic number, or from Polo's family nickname Emilione), was written in Old French and entitled Le divisament dou monde ("The description of the world"). The book was soon translated into many European languages and is known in English as The Travels of Marco Polo. The original is lost and there are now several often-conflicting versions of the translations. The book became an instant success — quite an achievement in a time when printing was not known in Europe.

Later life

Marco Polo was finally released from captivity in the summer of 1299, and he returned home to Venice, where his father and uncles had bought a large house in the central quarter named contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo with the company's profits.

The company continued its activities, and Marco was now a wealthy merchant. While he personally financed other expeditions, he would never leave Venice again. In 1300, he married Donata Badoer, a woman from an old, respected patrician family. Marco would have three children with her: Fantina, Bellela and Moreta. All of them later married into noble families.

Between 1310 and 1320, he wrote a new version of his book, Il Milione, in Italian. The text was lost, but not before a Franciscan friar, named Francesco Pipino, translated it into Latin. This Latin version was then translated back into the Italian, creating conflicts between different editions of the book.

Marco Polo died in his home on January 1324, at almost 70 years old. He was buried in the Church of San Lorenzo.

Did the trip really take place?

According to a famous story, a priest begged Marco on his deathbed to confess that he had lied in his stories. Marco refused, insisting, "I have not told half of what I saw!" This anecdote is an example of the skepticism that welcomed Marco's tales during his life.

In recent times, while most historians believe Marco Polo did reach China, some have proposed he did not get that far and only retold information he had heard from others. Those skeptics point out that among other omissions, his account fails to mention Chinese writing, chopsticks, tea, foot binding or the Great Wall (although in the last case this should not be surprising given that the wall was not built at its present location until the Ming Dynasty). Also, Chinese records of the time do not mention him, despite the fact that he claimed to have served as a special emissary for Kublai Khan—which is puzzling, given the careful record-keeping in China at that time.

On the other hand, Marco describes other aspects of Far Eastern life in much detail: paper money, the Grand Canal, the structure of a Mongol army, tigers, the Imperial postal system, the sea route from China to the Middle East (including references to Sumatra, Java (as Java major and Java minor respectively) and the Philippines) and the existence of rhinoceros in Sumatra. He also refers to Japan by its Chinese name "Zipang" or Cipangu. This is usually considered the first mention of Japan in Western literature. However, it is possible that Marco heard of these things from Arab silk road traders. Trade between the Middle East and Far East was flourishing and travellers are often happy to retell stories of their ventures in great detail.

In his defense, much of what he did not mention is circumstantial and there are no known arguments today to refute any of the descriptions he wrote about. Additionally, Marco gives a detailed account of accompanying an embassy from China to the Khan of Persia and of the delivery of Princess Kökechin for marriage to the Khan. Both Chinese and Persian annals mention this mission and include the names of the envoys; but the additional information about the journey which Marco provides is such that, one can reasonably assume, he could only have known if he had been a member of that embassy.

Marco Polo is also believed to have described a bridge that later was the site of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, a battle that marked the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Historical and Cultural impact

Although the Polos were by no means the first Europeans to reach China overland (see, for example, Radhanites and Giovanni da Pian del Carpine), thanks to Marco's book their trip was the first to be widely known, and the best-documented until then.

Marco Polo's description of the Far East and its riches inspired Christopher Columbus's decision to try to reach those lands by a western route. A heavily annotated copy of Polo's book was among the belongings of Columbus.

Legend has it that Marco Polo introduced to Italy some products from China, including ice cream, the piñata and pasta, especially spaghetti. However these legends are not grounded in fact, and pasta on the Italian peninsula can be traced back to 400 BC, through decorations found on an Etruscan tomb.

The name Marco Polo was also given to a children's game (Marco Polo), a story in the science fiction series Doctor Who (Marco Polo) and a three-masted clipper ship built in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1851. The fastest ship of her day, Marco Polo was the first ship to sail around the world in under six months. Several ships of the Italian navy were named Marco Polo. The airport in Venice is named Marco Polo International Airport. See also the Marcopolo satellites.

The travels of Marco Polo are given an extended fantasy treatment in the Irish writer Donn Byrne's Messer Marco Polo, and in Gary Jennings' 1984 novel The Journeyer. He also appears as the pivotal character in Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities. Peter T. Cavallaro's novel The Wonderful Travels of Drake was inspired by Polo's travels.

In 1982, Giuliano Montaldo directed an ambitious television miniseries, simply titled "Marco Polo". The Italian financed project starred Ken Marshall as Marco Polo and guest-starred a handful of Academy Awards winning actors, like Denholm Elliott, F. Murray Abraham, Anne Bancroft, John Gielgud, John Houseman, Burt Lancaster and also Tony Lo Bianco and Leonard Nimoy. The music was scored by the famous Italian music composer Ennio Morricone. The miniseries won 2 Emmy Awards and was nominated for 6 more.

Was Polo Croat?

The tourism authorities of Korčula (Curzola) advertise it as the home of Marco Polo, based on a later legend that places the Polo family in the Dalmatian town of Sebenico (today Šibenik), later moving to Curzola (today Korčula) and then to Venice. The island was in Polo's time, part of the Republic of Venice, but today is part of Croatia. As a consequence in Croatia, Polo is often presented as Croatian . The popularity of this theory has increased in recent years in Croatia, even because of the political situation. Even the former Croatian president Franjo Tudjman claimed several time the Croaticy of Polo, even in front of official contests . Nevertheless, Venice is clearly indicated as Polo's birthplace in The Travels of Marco Polo.

Dalmatian origins

A possible Dalmatian origin of Polos Family is debated.

See also

- Radhanites

- Giovanni da Pian del Carpine

- William of Rubruck

- Odoric of Pordenone

- Rabban Bar Sauma

- Ibn Battuta

- Sino-Roman relations

- Foreign relations of Imperial China

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

External links

- Polo's travels

- Template:Dmoz

- Polo and China

- Marco Polo's Description of the World - from Frances Wood's book Did Marco Polo Go to China?

- F. Wood's "Did Marco Polo Go To China?" - A critical analysis of this theory by Dr Igor de Rachewiltz of the Australian National University

- Works by Marco Polo at Project Gutenberg

- Concordances of "Description of the World" based on the italian text

Biography resources dedicated to Marco Polo

References

- Hart, Henry H., Marco Polo, Venetian Adventurer, University of Oklahoma Press, 1967

- Larner, John, Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World, Yale University Press, 1999

- Wood, Frances, Did Marco Polo Go to China?, Westview Press, 1995

- Yule, Henry (Ed.), The Travels of Marco Polo, Dover Publications, New York, 1983