This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Steelpillow (talk | contribs) at 09:07, 31 January 2015 (Undid revision 644949505 by Tomruen (talk) policy not picky. BRD applies, let''s talk). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:07, 31 January 2015 by Steelpillow (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 644949505 by Tomruen (talk) policy not picky. BRD applies, let''s talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| |||||||||

| Schläfli symbol 2<2q<p gcd(p,q)=1 |

{p/q} | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertices and Edges | p | ||||||||

| Density | q | ||||||||

| Coxeter diagram | |||||||||

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (Dp) | ||||||||

| Dual polygon | Self-dual | ||||||||

| Internal angle (degrees) |

|||||||||

A regular star polygon (not to be confused with a star-shaped polygon or a star domain) is a regular non-convex polygon. Only the regular star polygons have been studied in any depth; star polygons in general appear not to have been formally defined.

Etymology

Modern star-polygon names combine a numeral prefix, such as penta-, with the Greek suffix -gram (in this case generating the word pentagram). The prefix is normally a Greek cardinal, but synonyms using other prefixes exist. For example, a nine-pointed polygon or enneagram is also known as a nonagram, using the ordinal nona from Latin.

Although this prefix+suffix formula can generate or find star-polygon names, it does not necessarily reflect each word's history. For example, pentagram derives from pentagrammos / pentegrammos ("five lines") whose -grammos derives from grammē meaning "line". The -gram suffix, however, derives from gramma meaning "to write". Gramma and grammē do however resemble each other closely in sound, writing (γράμμα, γραμμή) and meaning ("written character, letter, that which is drawn", "stroke or line of a pen,") and are possibly cognates.

Regular star polygons

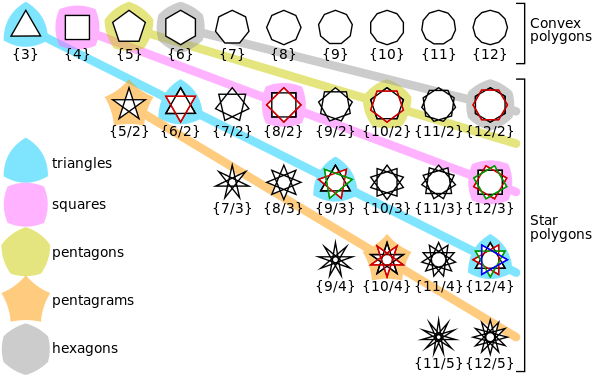

In geometry, a "regular star polygon" is a self-intersecting, equilateral equiangular polygon, created by connecting one vertex of a simple, regular, p-sided polygon to another, non-adjacent vertex and continuing the process until the original vertex is reached again. Alternatively for integers p and q, it can be considered as being constructed by connecting every qth point out of p points regularly spaced in a circular placement. For instance, in a regular pentagon, a five-pointed star can be obtained by drawing a line from the first to the third vertex, from the third vertex to the fifth vertex, from the fifth vertex to the second vertex, from the second vertex to the fourth vertex, and from the fourth vertex to the first vertex. The notation for such a polygon is {p/q} (see Schläfli symbol), which is equal to {p/p-q}. Regular star polygons will be produced when p and q are relatively prime (they share no factors). A regular star polygon can also be represented as a sequence of stellations of a convex regular core polygon. Regular star polygons were first studied systematically by Thomas Bradwardine.

Examples

Star figures

hexagram

2{3} or {6/2}

enneagram

3{3} or {9/3}

If the number of sides n is divisible by m, the star polygon obtained will be a regular polygon with n/m sides. A new figure is obtained by rotating these regular n/m-gons one vertex to the left on the original polygon until the number of vertices rotated equals n/m minus one, and combining these figures. An extreme case of this is where n/m is 2, producing a figure consisting of n/2 straight line segments; this is called a "degenerate star polygon".

In other cases where n and m have a common factor, a star polygon for a lower n is obtained, and rotated versions can be combined. These figures are called "star figures" or "improper star polygons" or "compound polygons". The same notation {n/m} is often used for them, although authorities such as Grünbaum (1994) regard (with some justification) the form k{n} as being more correct, where usually k = m.

A further complication comes when we compound two or more star polygons, as for example two pentagrams, differing by a rotation of 36°, inscribed in a decagon. This is correctly written in the form k{n/m}, as 2{5/2}, rather than the commonly used {10/4}.

A six-pointed star, like a hexagon, can be created using a compass and a straight edge:

- Make a circle of any size with the compass.

- Without changing the radius of the compass, set its pivot on the circle's circumference, and find one of the two points where a new circle would intersect the first circle.

- With the pivot on the last point found, similarly find a third point on the circumference, and repeat until six such points have been marked.

- With a straight edge, join alternate points on the circumference to form two overlapping equilateral triangles.

Symmetry

Regular star polygons and star figures can be thought of as diagramming cosets of the subgroups of the finite group .

The symmetry group of {n/k} is dihedral group Dn of order 2n, independent of k.

Irregular star polygons

A star polygon need not be regular. Irregular cyclic star polygons occur as vertex figures for the uniform polyhedra, defined by the sequence of regular polygon faces around each vertex, allowing for both multiple turns, and retrograde directions. (See vertex figures at List of uniform polyhedra)

The final stellation of the icosahedron can be seen as a polyhedron with irregular {9/4} star polygon faces with Dih3 dihedral symmetry.

The unicursal hexagram is another example of a cyclic irregular star polygon, containing Dih2 dihedral symmetry.

Interiors of star polygons

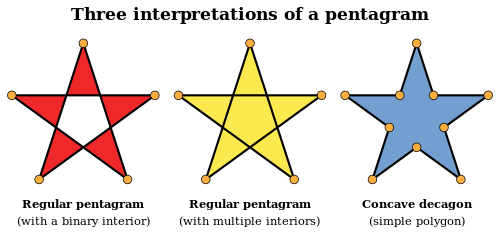

Star polygons leave an ambiguity of interpretation for interiors. This diagram demonstrates three interpretations of a pentagram.

- The left-hand interpretation has the 5 vertices of a regular pentagon connected alternately on a cyclic path, skipping alternate vertices. The interior is everything immediately left (or right) from each edge (until the next intersection). This makes the core convex pentagonal region actually "outside", and in general you can determine inside by a binary even-odd rule of counting how many edges are intersected from a point along a ray to infinity.

- The middle interpretation also has the 5 vertices of a regular pentagon connected alternately on a cyclic path. The interior may be treated either:

- as the inside of a simple 10-sided polygon perimeter boundary, as below.

- with the central convex pentagonal region surrounded twice, because the starry perimeter winds around it twice.

- The right-hand interpretation creates new vertices at the intersections of the edges (5 in this case) and defines a new concave decagon (10-pointed polygon) formed by perimeter path of the middle interpretation; it is in fact no longer a pentagram.

What is the area inside the pentagram? Each interpretation leads to a different answer.

Example interpretations of a star prism

Heptagrams with 2-sided interior |

Heptagrams with a simple perimeter interior |

The heptagrammic prism above shows different interpretations can create very different appearances.

Builders of polyhedron models, like Magnus Wenninger, usually represent star polygon faces in the concave form, without internal edges shown.

Star polygons in art and culture

Main article: Star polygons in art and cultureStar polygons feature prominently in art and culture. Such polygons may or may not be regular but they are always highly symmetrical. Examples include:

- The {5/2} star pentagon is also known as a pentagram, pentalpha or pentangle, and historically has been considered by many magical and religious cults to have occult significance.

- The simplest compound star polygon is two opposed triangles, sometimes written as {6/2} or 2{3} and known variously as the hexagram, (Star of David or Seal of Solomon).

- The {7/3} and {7/2} star polygons which are known as heptagrams and also have occult significance, particularly in the Kabbalah and in Wicca.

- The compound of two squares, sometimes written as {8/2} or 2{4}, is known in Hinduism as the Star of Lakshmi and in Islam as the Rub el Hizb.

- The {8/3} star polygon (octagram), and the compound {16/6} (or 2{8/3}) are frequent geometrical motifs in Mughal Islamic art and architecture; the first is on the emblem of Azerbaijan.

- An eleven pointed star called the hendecagram was used on the tomb of Shah Nemat Ollah Vali.

An {8/3} star polygon (octagram) constructed in an octagon |

Seal of Solomon (interlaced hexagram, with circle and dots) |

2{4} star figure |

2{8/3} star figure |

See also

- Complex polygon

- List of regular polytopes – Nonconvex forms (2D)

- Magic star

- Star polyhedron

- Star polychoron (4-polytopes)

- Star-shaped polygon

- Stellation#Stellating polygons

References

- Kappraff, Jay (2002). Beyond measure: a guided tour through nature, myth, and number. World Scientific. p. 258. ISBN 978-981-02-4702-7.

- γραμμή, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Coxeter, Harold Scott Macdonald (1973). Regular polytopes. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-61480-9.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Star Polygon". MathWorld.

- H. S. M. Coxeter, M. S. Longuet-Higgins, J. C. P. Miller, Uniform polyhedra, Phil. Trans. 1954 (Tables 6-8)

- Cromwell, P.; Polyhedra, CUP, Hbk. 1997, ISBN 0-521-66432-2. Pbk. (1999), ISBN 0-521-66405-5. p.175

- Grünbaum, B. and G.C. Shephard; Tilings and Patterns, New York: W. H. Freeman & Co., (1987), ISBN 0-7167-1193-1.

- Grünbaum, B.; Polyhedra with Hollow Faces, Proc of NATO-ASI Conference on Polytopes ... etc. (Toronto 1993), ed T. Bisztriczky et al., Kluwer Academic (1994) pp. 43–70.

- John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strass, The Symmetries of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 26. pp. 404: Regular star-polytopes Dimension 2)

External links

| Polygons (List) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triangles | |||||||

| Quadrilaterals | |||||||

| By number of sides |

| ||||||

| Star polygons | |||||||

| Classes | |||||||

of the

of the  .

.