This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) at 19:52, 12 December 2013 (Reverting possible vandalism by 78.133.45.148 to version by Pinethicket. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1617210) (Bot)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:52, 12 December 2013 by ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) (Reverting possible vandalism by 78.133.45.148 to version by Pinethicket. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1617210) (Bot))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (March 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. Please review the contents of the article and add the appropriate references if you can. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Effects of cannabis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2013) |  |

The effects of cannabis are caused by chemical compounds in cannabis, including cannabinoids such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Cannabis has both psychological and physiological effects on the human body. Five European countries, Canada, and twenty US states have legalized medical cannabis if prescribed for nausea, pain or the alleviation of symptoms surrounding chronic illness.

Marijuana use disorder is defined in the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and a 2013 literature review said that exposure to marijuana had biologically-based physical, mental, behavioral and social health consequences and was "associated with diseases of the liver (particularly with co-existing hepatitis C), lungs, heart, and vasculature".

In large enough doses, THC can induce auditory and visual hallucination. Acute effects while under the influence can include both euphoria and anxiety. Concerns have been raised about the potential for long-term cannabis consumption to increase risk for schizophrenia, depersonalization disorder, bipolar disorders, and major depression, however studies are inconclusive and the ultimate conclusions on these factors are disputed. The evidence of long-term effects on memory is preliminary and hindered by confounding factors. Some people claim that cannabis has mystical effects.

Biochemical effects

Cannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors

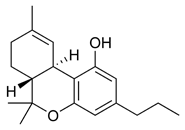

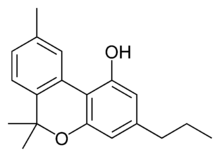

The most prevalent psychoactive substances in cannabis are cannabinoids, most notably THC. Some varieties, having undergone careful selection and growing techniques, can yield as much as 29% THC. Another psychoactive cannabinoid present in Cannabis sativa is tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), but it is only found in small amounts and is a cannabinoid antagonist.

In addition, there are also similar compounds contained in cannabis that do not exhibit any psychoactive response but are obligatory for functionality: cannabidiol (CBD), an isomer of THC; cannabinol (CBN), an oxidation product of THC; cannabivarin (CBV), an analog of CBN with a different sidechain, cannabidivarin (CBDV), an analog of CBD with a different side chain, and cannabinolic acid. How these other compounds interact with THC is not fully understood. Some clinical studies have proposed that CBD acts as a balancing force to regulate the strength of the psychoactive agent THC. CBD is also believed to regulate the body’s metabolism of THC by inactivating cytochrome P450, an important class of enzymes that metabolize drugs. Experiments in which mice were treated with CBD followed by THC showed that CBD treatment was associated with a substantial increase in brain concentrations of THC and its major metabolites, most likely because it decreased the rate of clearance of THC from the body. Cannabis cofactor compounds have also been linked to lowering body temperature, modulating immune functioning, and cell protection. The essential oil of cannabis contains many fragrant terpenoids which may synergize with the cannabinoids to produce their unique effects. THC is converted rapidly to 11-hydroxy-THC, which is also pharmacologically active, so the drug effect outlasts measurable THC levels in blood.

THC and cannabidiol are also neuroprotective antioxidants. Research in rats has indicated that THC prevented hydroperoxide-induced oxidative damage as well as or better than other antioxidants in a chemical (Fenton reaction) system and neuronal cultures. Cannabidiol was significantly more protective than either vitamin E or vitamin C.

The cannabinoid receptor is a typical member of the largest known family of receptors called a G protein-coupled receptor. A signature of this type of receptor is the distinct pattern of how the receptor molecule spans the cell membrane seven times. The location of cannabinoid receptors exists on the cell membrane, and both outside (extracellularly) and inside (intracellularly) the cell membrane. CB1 receptors, the bigger of the two, are extraordinarily abundant in the brain: 10 times more plentiful than μ-opioid receptors, the receptors responsible for the effects of morphine. CB2 receptors are structurally different (the sequence similarity between the two subtypes of receptors is 44%), found only on cells of the immune system, and seems to function similarly to its CB1 counterpart. CB2 receptors are most commonly prevalent on B-cells, natural killer cells, and monocytes, but can also be found on polymorphonuclear neutrophil cells, T8 cells, and T4 cells. In the tonsils the CB2 receptors appear to be restricted to B-lymphocyte-enriched areas.

THC and endogenous anandamide additionally interact with glycine receptors.

Biochemical mechanisms in the brain

See also: Cannabis (drug) § Mechanism of actionIn 1990 the discovery of cannabinoid receptors located throughout the brain and body, along with endogenous cannabinoid neurotransmitters like anandamide (a lipid material derived ligand from arachidonic acid), suggested that the use of cannabis affects the brain in the same manner as a naturally occurring brain chemical. Cannabinoids usually contain a 1,1'-di-methyl-pyrane ring, a variedly derivatized aromatic ring and a variedly unsaturated cyclohexyl ring and their immediate chemical precursors, constituting a family of about 60 bi-cyclic and tri-cyclic compounds. Like most other neurological processes, the effects of cannabis on the brain follow the standard protocol of signal transduction, the electrochemical system of sending signals through neurons for a biological response. It is now understood that cannabinoid receptors appear in similar forms in most vertebrates and invertebrates and have a long evolutionary history of 500 million years. The binding of cannabinoids to cannabinoid receptors decrease adenylyl cyclase activity, inhibit calcium N channels, and disinhibit KA channels. There are two types of cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2).

The CB1 receptor is found primarily in the brain and mediates the psychological effects of THC. The CB2 receptor is most abundantly found on cells of the immune system. Cannabinoids act as immunomodulators at CB2 receptors, meaning they increase some immune responses and decrease others. For example, nonpsychotropic cannabinoids can be used as a very effective anti-inflammatory. The affinity of cannabinoids to bind to either receptor is about the same, with only a slight increase observed with the plant-derived compound CBD binding to CB2 receptors more frequently. Cannabinoids likely have a role in the brain’s control of movement and memory, as well as natural pain modulation. It is clear that cannabinoids can affect pain transmission and, specifically, that cannabinoids interact with the brain's endogenous opioid system and may affect dopamine transmission. This is an important physiological pathway for the medical treatment of pain.

Sustainability in the body

Main article: Cannabis drug testingMost cannabinoids are lipophilic (fat soluble) compounds that are easily stored in fat, thus yielding a long elimination half-life relative to other recreational drugs. The THC molecule, and related compounds, are usually detectable in drug tests from 3 days up to 10 days according to Redwood Laboratories; heavy users can produce positive tests for up to 3 months after ceasing cannabis use (see drug test).

Toxicity

No fatal overdoses associated with cannabis use have been reported as of 2010. A review published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in February 2001 said that "no deaths directly due to acute cannabis use ha ever been reported".

THC, the principal psychoactive constituent of the cannabis plant, has an extremely low toxicity and the amount that can enter the body through the consumption of cannabis plants poses no threat of death. In lab animal tests, scientists have had much difficulty administering a dosage of THC that is high enough to be lethal.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Effects of cannabis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

According to the Merck Index, the LD50 of THC (the dose which causes the death of 50% of individuals) is 1270 mg/kg for male rats and 730 mg/kg for female rats from oral consumption in sesame oil, and 42 mg/kg for rats from inhalation.

The ratio of cannabis material required to produce a fatal overdose to the amount required to saturate cannabinoid receptors and cause intoxication is approximately 40,000:1. It was found in 2007 that while tobacco and cannabis smoke are quite similar, cannabis smoke contained higher amounts of ammonia, hydrogen cyanide, and nitrogen oxides, but lower levels of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). This study found that directly inhaled cannabis smoke contained as much as 20 times as much ammonia and 5 times as much hydrogen cyanide as tobacco smoke and compared the properties of both mainstream and sidestream (smoke emitted from a smouldering 'joint' or 'cone') smoke. Mainstream cannabis smoke was found to contain higher concentrations of selected polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) than sidestream tobacco smoke. However, other studies have found much lower disparities in ammonia and hydrogen cyanide between cannabis and tobacco, and that some other constituents (such as polonium-210, lead, arsenic, nicotine, and tobacco-specific nitrosamines) are either lower or non-existent in cannabis smoke.

Cannabis smoke contains thousands of organic and inorganic chemical compounds. This tar is chemically similar to that found in tobacco smoke or cigars. Over fifty known carcinogens have been identified in cannabis smoke. These include nitrosamines, reactive aldehydes, and polycylic hydrocarbons, including benzpyrene. Marijuana smoke was listed as a cancer agent in California in 2009. A study by the British Lung Foundation published in 2012 identifies cannabis smoke as a carcinogen and also finds awareness of the danger is low compared with the high awareness of the dangers of smoking tobacco particularly among younger users. Other observations include possible increased risk from each cigarette; lack of research on the effect of cannabis smoke alone; low rate of addiction compared to tobacco; and episodic nature of cannabis use compared to steady frequent smoking of tobacco. Professor David Nutt, a UK drug expert, points out that the study cited by the British Lung Foundation has been accused of both “false reasoning” and “incorrect methodology”. Further, he notes that other studies have failed to connect cannabis with lung cancer, and accuses the BLF of "scaremongering over cannabis".

Short-term effects

When smoked, the short-term effects of cannabis manifest within seconds and are fully apparent within a few minutes, typically lasting for 1–3 hours, varying by the person and the strain of cannabis. The duration of noticeable effects has been observed to diminish due to prolonged, repeated use and the development of a tolerance to cannabinoids.

Psychoactive effects

See also: Medical cannabis § StrainsThe psychoactive effects of cannabis, known as a "high", are subjective and can vary based on the person and the method of use.

When THC enters the blood stream and reaches the brain, it binds to cannabinoid receptors. The endogenous ligand of these receptors is anandamide, the effects of which THC emulates. This agonism of the cannabinoid receptors results in changes in the levels of various neurotransmitters, especially dopamine and norepinephrine; neurotransmitters which are closely associated with the acute effects of cannabis ingestion, such as euphoria and anxiety. Some effects may include a general alteration of conscious perception, euphoria, feelings of well-being, relaxation or stress reduction, increased appreciation of humor, music (especially discerning its various components/instruments) or the arts, joviality, metacognition and introspection, enhanced recollection (episodic memory), increased sensuality, increased awareness of sensation, increased libido, and creativity. Abstract or philosophical thinking, disruption of linear memory and paranoia or anxiety are also typical. Anxiety is the most commonly reported side effect of smoking marijuana. Between 20 and 30 percent of recreational users experience intense anxiety and/or panic attacks after smoking cannabis, however, some report anxiety only after not smoking cannabis for a prolonged period of time.

Cannabis also produces many subjective and highly tangible effects, such as greater enjoyment of food taste and aroma, an enhanced enjoyment of music and comedy, and marked distortions in the perception of time and space (where experiencing a "rush" of ideas from the bank of long-term memory can create the subjective impression of long elapsed time, while a clock reveals that only a short time has passed). At higher doses, effects can include altered body image, auditory and/or visual illusions, pseudo-hallucinatory, and ataxia from selective impairment of polysynaptic reflexes. In some cases, cannabis can lead to dissociative states such as depersonalization and derealization; such effects are most often considered desirable, but have the potential to induce panic attacks and paranoia in some unaccustomed users.

Any episode of acute psychosis that accompanies cannabis use usually abates after 6 hours, but in rare instances heavy users may find the symptoms continuing for many days. When the episode is accompanied by aggression, sedation or physical restraint may be necessary.

While many psychoactive drugs clearly fall into the category of either stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogen, cannabis exhibits a mix of all properties, perhaps leaning the most towards hallucinogenic or psychedelic properties, though with other effects quite pronounced as well. THC is typically considered the primary active component of the cannabis plant; various scientific studies have suggested that certain other cannabinoids like CBD may also play a significant role in its psychoactive effects.

Somatic effects

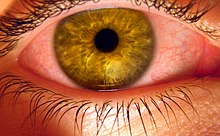

Some of the short-term physical effects of cannabis use include increased heart rate, dry mouth, reddening of the eyes (congestion of the conjunctival blood vessels), a reduction in intra-ocular pressure, muscle relaxation and a sensation of cold or hot hands and feet.

Electroencephalography or EEG shows somewhat more persistent alpha waves of slightly lower frequency than usual. Cannabinoids produce a "marked depression of motor activity" via activation of neuronal cannabinoid receptors belonging to the CB1 subtype.

Duration

Effects of cannabis generally range from 10 minutes to 8 hours, depending on the potency of the dose, other drugs consumed, route of administration, set, setting, and personal tolerance to the drug's various effects.

Smoked

The total short-term duration of cannabis use when smoked is based on the potency and how much is smoked. Effects can typically last two to three hours.

A study of ten healthy, robust, male volunteers who resided in a residential research facility sought to examine both acute and residual subjective, physiologic, and performance effects of smoking marijuana. On three separate days, subjects smoked one NIDA marijuana cigarette containing either 0%, 1.8%, or 3.6% THC, documenting subjective, physiologic, and performance measures prior to smoking, five times following smoking on that day, and three times on the following morning. Subjects reported robust subjective effects following both active doses of marijuana, which returned to baseline levels within 3.5 hours. Heart rate increased and the pupillary light reflex decreased following active dose administration with return to baseline on that day. Additionally, marijuana smoking acutely produced decrements in smooth pursuit eye tracking. Although robust acute effects of marijuana were found on subjective and physiological measures, no effects were evident the day following administration, indicating that the residual effects of smoking a single marijuana cigarette are minimal.

A Dutch double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study examining male volunteers aged 18–45 years with a self-reported history of regular cannabis use concluded that smoking of cannabis with very high THC levels (marijuana with 9–23% THC), as currently sold in coffee shops in the Netherlands, may lead to higher THC blood-serum concentrations. This is reflected by an increase of the occurrence of impaired psychomotor skills, particularly among younger or inexperienced cannabis smokers, who do not always adapt their smoking-style to the higher THC content. High THC concentrations in cannabis were associated with a dose-related increase of physical effects (such as increase of heart rate, and decrease of blood pressure) and psychomotor effects (such as reacting more slowly, decreased ability to focus and concentrate, making more mistakes during performance testing, having less motor control, and experiencing drowsiness). It was also observed during the study that the effects from a single joint lasted for more than eight hours. Reaction times remained impaired five hours after smoking, when the THC serum concentrations were significantly reduced, but still present. However, it is important to note that the subjects (without knowing the potency) were told to finish their (unshared) joints rather than titrate their doses, leading in many cases to significantly higher doses than they would normally take. Also, when subjects smoke on several occasions per day, accumulation of THC in blood-serum may occur.

Oral

When taken orally (in the form of capsules, food or drink), the psychoactive effects take longer to manifest and generally last longer, typically lasting for 4–10 hours after consumption. Very high doses may last even longer. Also, oral ingestion use eliminates the need to inhale toxic combustion products created by smoking and therefore reduces the risk of respiratory harm associated with cannabis smoking.

Neurological effects

The areas of the brain where cannabinoid receptors are most prevalently located are consistent with the behavioral effects produced by cannabinoids. Brain regions in which cannabinoid receptors are very abundant are the basal ganglia, associated with movement control; the cerebellum, associated with body movement coordination; the hippocampus, associated with learning, memory, and stress control; the cerebral cortex, associated with higher cognitive functions; and the nucleus accumbens, regarded as the reward center of the brain. Other regions where cannabinoid receptors are moderately concentrated are the hypothalamus, which regulates homeostatic functions; the amygdala, associated with emotional responses and fears; the spinal cord, associated with peripheral sensations like pain; the brain stem, associated with sleep, arousal, and motor control; and the nucleus of the solitary tract, associated with visceral sensations like nausea and vomiting.

Most notably, the two areas of motor control and memory are where the effects of cannabis are directly and irrefutably evident. Cannabinoids, depending on the dose, inhibit the transmission of neural signals through the basal ganglia and cerebellum. At lower doses, cannabinoids seem to stimulate locomotion while greater doses inhibit it, most commonly manifested by lack of steadiness (body sway and hand steadiness) in motor tasks that require a lot of attention. Other brain regions, like the cortex, the cerebellum, and the neural pathway from cortex to striatum, are also involved in the control of movement and contain abundant cannabinoid receptors, indicating their possible involvement as well.

Experiments on animal and human tissue have demonstrated a disruption of short-term memory formation, which is consistent with the abundance of CB1 receptors on the hippocampus, the region of the brain most closely associated with memory. Cannabinoids inhibit the release of several neurotransmitters in the hippocampus such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and glutamate, resulting in a major decrease in neuronal activity in that region. This decrease in activity resembles a "temporary hippocampal lesion."

In in-vitro experiments THC at extremely high concentrations, which could not be reached with commonly consumed doses, caused competitive inhibition of the AChE enzyme and inhibition of β-amyloid peptide aggregation, implicated in the development of Alzheimer's disease. Compared to currently approved drugs prescribed for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, THC is a considerably superior inhibitor of A aggregation, and this study provides a previously unrecognized molecular mechanism through which cannabinoid molecules may impact the progression of this debilitating disease.

Effects on driving

Cannabis usage has been shown to have a negative effect on driving ability. The British Medical Journal indicated that "drivers who consume cannabis within three hours of driving are nearly twice as likely to cause a vehicle collision as those who are not under the influence of drugs or alcohol".

In Cannabis and driving: a review of the literature and commentary, the United Kingdom's Department for Transport reviewed data on cannabis and driving, finding "Cannabis impairs driving behaviour. However, this impairment is mediated in that subjects under cannabis treatment appear to perceive that they are indeed impaired. Where they can compensate, they do, for example ... effects of driving behaviour are present up to an hour after smoking but do not continue for extended periods". The report summarizes current knowledge about the effects of cannabis on driving and accident risk based on a review of available literature published since 1994 and the effects of cannabis on laboratory based tasks. The study identified young males, amongst whom cannabis consumption is frequent and increasing, and in whom alcohol consumption is also common, as a risk group for traffic accidents. The cause, according to the report, is driving inexperience and factors associated with youth relating to risk taking, delinquency and motivation. These demographic and psychosocial variables may relate to both drug use and accident risk, thereby presenting an artificial relationship between use of drugs and accident involvement.

Kelly, Darke and Ross show similar results, with laboratory studies examining the effects of cannabis on skills utilised while driving showing impairments in tracking, attention, reaction time, short-term memory, hand-eye coordination, vigilance, time and distance perception, and decision making and concentration. An EMCDDA review concluded that "the acute effect of moderate or higher doses of cannabis impairs the skills related to safe driving and injury risk", specifically "attention, tracking and psychomotor skills". In their review of driving simulator studies, Kelly et al. conclude that there is evidence of dose-dependent impairments in cannabis-affected drivers' ability to control a vehicle in the areas of steering, headway control, speed variability, car following, reaction time and lane positioning. The researchers note that "even in those who learn to compensate for a drug's impairing effects, substantial impairment in performance can still be observed under conditions of general task performance (i.e. when no contingencies are present to maintain compensated performance)."

A report from the University of Colorado, Montana State University, and the University of Oregon found that on average, states that have legalized Medical cannabis had a decrease in traffic-related fatalities by 8-11%. The researchers hypothesized "it’s just safer to drive under the influence of marijuana than it is drunk....Drunk drivers take more risk, they tend to go faster. They don’t realize how impaired they are. People who are under the influence of marijuana drive slower, they don’t take as many risks”. Another consideration, they added, was the fact that users of marijuana tend not to go out as much.

Cardiovascular effects

Short term (one to two hours) effects on the cardiovascular system can include increased heart rate, dilation of blood vessels, and fluctuations in blood pressure. There are medical reports of occasional infarction, stroke and other cardiovascular side effects. Marijuana's cardiovascular effects are not associated with serious health problems for most young, healthy users. Researchers reported in the International Journal of Cardiology, "Marijuana use by older people, particularly those with some degree of coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease, poses greater risks due to the resulting increase in catecholamines, cardiac workload, and carboxyhemoglobin levels, and concurrent episodes of profound postural hypotension. Indeed, marijuana may be a much more common cause of myocardial infarction than is generally recognized. In day-to-day practice, a history of marijuana use is often not sought by many practitioners, and even when sought, the patient's response is not always truthful".

A 2013 analysis of 3,886 myocardial infarction survivors over an 18-year period showed "no statistically significant association between marijuana use and mortality".

A 2008 study by the National Institutes of Health Biomedical Research Centre in Baltimore found that heavy, chronic smoking of marijuana (138 joints per week) changed blood proteins associated with heart disease and stroke. This may be a result of raised carboxyhemoglobin levels from carbon monoxide. A similar increase in heart disease and ischemic strokes is observed in tobacco smokers, which suggests that the harmful effects come from a variety of combustion products, not just marijuana.

A 2000 study by researchers at Boston's Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health found that a middle-age person's risk of heart attack rises nearly fivefold in the first hour after smoking marijuana, "roughly the same risk seen within an hour of sexual activity".

Cannabis arteritis is a very rare peripheral vascular disease similar to Buerger's disease. There were about 50 confirmed cases from 1960 to 2008, all of which occurred in Europe. However, all of the cases also involved tobacco (a known cause of Buerger's disease) in one way or another, and nearly all of the cannabis use was quite heavy . In Europe, cannabis is typically mixed with tobacco, in contrast to North America.

Combination with other drugs

The most obvious confounding factor in cannabis research is the prevalent usage of other recreational drugs, especially alcohol and nicotine. Such complications demonstrate the need for studies on cannabis that have stronger controls, and investigations into alleged symptoms of cannabis use that may also be caused by tobacco. Some critics question whether agencies doing the research make an honest effort to present an accurate, unbiased summary of the evidence, or whether they "cherry-pick" their data to please funding sources which may include the tobacco industry or governments dependent on cigarette tax revenue; others caution that the raw data, and not the final conclusions, are what should be examined.

Cannabis also has been shown to have a synergistic cytotoxic effect on lung cancer cell cultures in vitro with the food additive butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and possibly the related compound butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). The study concluded, "Exposure to marijuana smoke in conjunction with BHA, a common food additive, may promote deleterious health effects in the lung." BHA & BHT are human-made fat preservatives, and are found in many packaged foods including: plastics in boxed cereal, Jello, Slim Jims, and more.

The Australian National Household Survey of 2001 showed that cannabis in Australia is rarely used without other drugs. 95% of cannabis users also drank alcohol; 26% took amphetamines; 19% took ecstasy and only 2.7% reported not having used any other drug with cannabis. While research has been undertaken on the combined effects of alcohol and cannabis on performing certain tasks, little research has been conducted on the reasons why this combination is so popular. Evidence from a controlled experimental study undertaken by Lukas and Orozco suggests that alcohol causes THC to be absorbed more rapidly into the blood plasma of the user. Data from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing found that three-quarters of recent cannabis users reported using alcohol when cannabis was not available.

Memory and learning

Studies on cannabis and memory are hindered by small sample sizes, confounding drug use, and other factors. The strongest evidence regarding cannabis and memory focuses on its temporary negative effects on short-term and working memory.

In a 2001 study looking at neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users, researchers found "some cognitive deficits appear detectable at least 7 days after heavy cannabis use but appear reversible and related to recent cannabis exposure rather than irreversible and related to cumulative lifetime use". On his studies regarding cannabis use, lead researcher and Harvard professor Harrison Pope said he found marijuana is not dangerous over the long term, but there are short-term effects. From neuropsychological tests, Pope found that chronic cannabis users showed difficulties, with verbal memory in particular, for "at least a week or two" after they stopped smoking. Within 28 days, memory problems vanished and the subjects “were no longer distinguishable from the comparison group”.

Researchers from the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine failed to show substantial, systemic neurological effects from long-term recreational use of cannabis. Their findings were published in the July 2003 issue of the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. The research team, headed by Dr Igor Grant, found that cannabis use did affect perception, but did not cause permanent brain damage. Researchers looked at data from 15 previously published controlled studies involving 704 long-term cannabis users and 484 nonusers. The results showed long-term cannabis use was only marginally harmful on the memory and learning. Other functions such as reaction time, attention, language, reasoning ability, perceptual and motor skills were unaffected. The observed effects on memory and learning, they said, showed long-term cannabis use caused "selective memory defects", but that the impact was "of a very small magnitude". A study at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine showed that very heavy use of marijuana is associated with decrements in neurocognitive performance even after 28 days of abstinence.

Appetite

The feeling of increased appetite following the use of cannabis has been documented for hundreds of years, and is known colloquially as "the munchies" in popular culture. Clinical studies and survey data have found that cannabis increases food enjoyment and interest in food. Scientists have claimed to be able to explain what causes the increase in appetite, concluding that "endocannabinoids in the hypothalamus activate cannabinoid receptors that are responsible for maintaining food intake". Rarely, chronic users experience a severe vomiting disorder, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, after smoking and find relief by taking hot baths.

Endogenous cannabinoids (“endocannabinoids”) were discovered in cow's milk and soft cheeses. Endocannabinoids were also found in human breast milk. It is widely accepted that the neonatal survival of many species "is largely dependent upon their suckling behavior, or appetite for breast milk" and recent research has identified the endogenous cannabinoid system to be the first neural system to display complete control over milk ingestion and neonatal survival. It is possible that "cannabinoid receptors in our body interact with the cannabinoids in milk to stimulate a suckling response in newborns so as to prevent growth failure".

Pathogens and microtoxins

Most microorganisms found in cannabis only affect plants and not humans, but some microorganisms, especially those that proliferate when the herb is not correctly dried and stored, can be harmful to humans. Some users may store marijuana in an airtight bag or jar in a refrigerator to prevent fungal and bacterial growth.

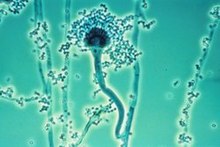

Fungi

The fungi Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus parasiticus, Aspergillus tamarii, Aspergillus sulphureus, Aspergillus repens, Mucor hiemalis (not a human pathogen), Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium italicum and Rhizopus nigrans have been found in moldy cannabis. Aspergillus mold species can infect the lungs via smoking or handling of infected cannabis and cause opportunistic and sometimes deadly aspergillosis. Some of the microorganisms found create aflatoxins, which are toxic and carcinogenic. Researchers suggest that moldy cannabis thus be discarded.

Mold is also found in smoke from mold infected cannabis, and the lungs and nasal passages are a major means of contracting fungal infections. Levitz and Diamond (1991) suggested baking marijuana in home ovens at 150 °C , for five minutes before smoking. Oven treatment killed conidia of A. fumigatus, A. flavus and A. niger, and did not degrade the active component of marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)."

Bacteria

Cannabis contaminated with Salmonella muenchen was positively correlated with dozens of cases of salmonellosis in 1981. "Thermophilic actinomycetes" were also found in cannabis.

Long-term effects

Main article: Long-term effects of cannabisExposure to marijuana has biologically-based physical, mental, behavioral and social health consequences and is "associated with diseases of the liver (particularly with co-existing hepatitis C), lungs, heart, and vasculature" according to a 2013 literature review by Gordon and colleagues.

Marijuana use disorder is defined in the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a condition requiring treatment.

Though the long-term effects of cannabis have been studied, debated topics include the drug's addictiveness, its potential as a "gateway drug", its effects on intelligence and memory, and its contributions to mental disorders such as schizophrenia and clinical depression. Research on the "gateway drug" hypothesis that cannabis and alcohol makes users more inclined to become addicted to "harder" drugs like cocaine and heroin has produced mixed results, with different studies finding varying degrees of correlation between the use of cannabis and other drugs, and some finding none.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Effects of cannabis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Several drugs have been investigated in an attempt to ameliorate the symptoms of cannabis withdrawal. Such drugs include bupropion, divalproex, nefazodone, lofexidine, and dronabinol. Of these, dronabinol has proven the most effective.

Effects in pregnancy

Main article: Cannabis in pregnancyCannabis consumption in pregnancy is associated with restrictions in growth of the fetus, miscarriage, and cognitive deficits in offspring. A 2012 systematic review found although it was difficult to draw firm conclusions, there was some evidence that prenatal exposure to certain substances, especially marijuana and cocaine, was associated with "deficits in language, attention, areas of cognitive performance, and delinquent behavior in adolescence". A report prepared for the Australian National Council on Drugs concluded cannabis and other cannabinoids are contraindicated in pregnancy as it may interact with the endocannabinoid system.

See also

References

- ^ Gordon AJ, Conley JW, Gordon JM (2013). "Medical consequences of marijuana use: a review of current literature". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 15 (12): 419. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0419-7. PMID 24234874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Osborne, Geraint B.; Fogel, Curtis (2008). "Understanding the Motivations for Recreational Marijuana Use Among Adult Canadians1". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (3–4): 539–72. doi:10.1080/10826080701884911.

- Ranganathan, Mohini; d'Souza, Deepak Cyril (2006). "The acute effects of cannabinoids on memory in humans: a review". Psychopharmacology. 188 (4): 425–44. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0508-y. PMID 17019571.

- Leweke, F. Markus; Koethe, Dagmar (2008). "Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction". Addiction Biology. 13 (2): 264–75. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00106.x. PMID 18482435.

- Rubino, T; Parolaro, D (2008). "Long lasting consequences of cannabis exposure in adolescence". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 286 (1–2 Suppl 1): S108–13. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.003. PMID 18358595.

- Michael Slezak (2009-09-01). "Doubt cast on cannabis, schizophrenia link". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 2013-01-08Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Boston Municipal Courtcentral Division. Docket # 0701CR7229" (PDF). 2008. Retrieved 2013-01-08Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Delisi, Lynn E (2008). "The effect of cannabis on the brain: can it cause brain anomalies that lead to increased risk for schizophrenia?". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 21 (2): 140–50. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f51266. PMID 18332661.

- Denson, TF; Earleywine, M (2006). "Decreased depression in marijuana users". Addictive behaviors. 31 (4): 738–42. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.052. PMID 15964704.

- Grotenhermen, Franjo (2007). "The Toxicology of Cannabis and Cannabis Prohibition". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 4 (8): 1744–69. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790151. PMID 17712818.

- ^ Riedel, G.; Davies, S. N. (2005). "Cannabinoid Function in Learning, Memory and Plasticity". Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 168 (168): 445–477. doi:10.1007/3-540-26573-2_15. ISBN 3-540-22565-X. PMID 16596784.

- Touw, Mia (1981). "The Religious and Medicinal Uses ofCannabisin China, India and Tibet". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 13 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1080/02791072.1981.10471447. PMID 7024492.

- ^ H.K. Kalant & W.H.E. Roschlau (1998). Principles of Medical Pharmacology (6th ed.). pp. 373–375.

- Turner, Carlton E.; Bouwsma, Otis J.; Billets, Steve; Elsohly, Mahmoud A. (1980). "Constituents ofCannabis sativa L. XVIII – Electron voltage selected ion monitoring study of cannabinoids". Biological Mass Spectrometry. 7 (6): 247–56. doi:10.1002/bms.1200070605.

- ^ J.E. Joy, S. J. Watson, Jr., and J.A. Benson, Jr, (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing The Science Base. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 0-585-05800-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hampson, A. J.; Grimaldi, M.; Axelrod, J.; Wink, D. (1998). "Cannabidiol and (−)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (14): 8268–73. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.8268H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.8268. PMC 20965. PMID 9653176.

- H. Abadinsky (2004). Drugs: An Introduction (5th ed.). pp. 62–77, 160–166. ISBN 0-534-52750-7.

- Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M (2010). "Does cannabis use increase the risk of death? Systematic review of epidemiological evidence on adverse effects of cannabis use". Drug Alcohol Rev (Review). 29 (3): 318–30. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00149.x. PMID 20565525.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ashton CH (2001). "Pharmacology and effects of cannabis: a brief review". Br J Psychiatry (Review). 178: 101–6. PMID 11157422.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - 1996. The Merck Index, 12th ed., Merck & Co., Rahway, New Jersey

- "Cannabis Chemistry". Erowid.orgTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/library/mjfaq1.htm

- ^ Moir, David; Rickert, William S.; Levasseur, Genevieve; Larose, Yolande; Maertens, Rebecca; White, Paul; Desjardins, Suzanne (2008). "A Comparison of Mainstream and Sidestream Marijuana and Tobacco Cigarette Smoke Produced under Two Machine Smoking Conditions". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 21 (2): 494–502. doi:10.1021/tx700275p. PMID 18062674.

- "Marijuana v.s. Tobacco smoke compositions". from: Institute of Medicine, Marijuana and Health, Washington, D.C. National Academy Press. Erowid.org. 1988. Retrieved 2013-01-09Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - David Malmo-Levine (2002-01-02). "Radioactive Tobacco". Retrieved 2013-01-09Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Gumbiner, Jann (17 February 2011). "Does Marijuana Cause Cancer?" (Document). Psychology TodayTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|format=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Does smoking cannabis cause cancer?" (Document). Cancer Research UK. 20 September 2010Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Tashkin, Donald (1997). "Effects of marijuana on the lung and its immune defenses" (Document). UCLA School of MedicineTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Chemicals known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity" (PDF). ca.gov. 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2013-01-08Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "The impact of cannabis on your lung" (Document). British Lung Association. 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Le, Bryan (2012-06-08). "Drug prof slams pot lung-danger claims" (Document). The FixTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Ashton, C. H. (2001). "Pharmacology and effects of cannabis: a brief review". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 178 (2): 101–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.2.101.

- ^ "Cannabis". Dasc.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 2011-04-20Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - http://cannabislink.ca/info/MotivationsforCannabisUsebyCanadianAdults-2008.pdf

- "Medical Marijuana and the Mind". Harvard Mental Health Letter. 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Medication-Associated Depersonalization Symptoms"Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Shufman, E; Lerner, A; Witztum, E (2005). "Depersonalization after withdrawal from cannabis usage" (PDF). Harefuah (in Hebrew). 144 (4): 249–51, 303. PMID 15889607.

- Johnson, BA (1990). "Psychopharmacological effects of cannabis". British journal of hospital medicine. 43 (2): 114–6, 118–20, 122. PMID 2178712.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G (20 March 2012). "Chapter 60: Marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) and synthetic cannabinoids". Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. John Wiley & Sons. p. 915. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6.

- Stafford, Peter (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley, California, United States: Ronin Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-914171-51-8.

- McKim, William A (2002). Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5 ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 0-13-048118-1.

- "Information on Drugs of Abuse". Commonly Abused Drug Chart. nih.gov.

- Moelker, Wendy (19 Sep 2008). "How does Marijuana Affect Your Body? What are the Marijuana Physical Effects?".

- H.K. Kalant & W.H.E. Roschlau (1998). Principles of Medical Pharmacology (6th ed.). pp. 373–375.

- Andersson, M.; Usiello, A; Borgkvist, A; Pozzi, L; Dominguez, C; Fienberg, AA; Svenningsson, P; Fredholm, BB; Borrelli, E; Greengard, P; Fisone, G (2005). "Cannabinoid Action Depends on Phosphorylation of Dopamine- and cAMP-Regulated Phosphoprotein of 32 kDa at the Protein Kinase A Site in Striatal Projection Neurons". Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (37): 8432–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1289-05.2005. PMID 16162925.

- Fant, R (1998). "Acute and Residual Effects of Marijuana in Humans". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 60 (4): 777–84. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(97)00386-9.

- Tj. T. Mensinga. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study on the pharmacokinetics and effects of cannabis (PDF). RIVM. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=1(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - http://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis_effects.shtml

- Pertwee, R (1997). "Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 74 (2): 129–80. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(97)82001-3.

- Eubanks, Lisa M.; Rogers, Claude J.; Beuscher Ae, 4th; Koob, George F.; Olson, Arthur J.; Dickerson, Tobin J.; Janda, Kim D. (2006). "A Molecular Link Between the Active Component of Marijuana and Alzheimer's Disease Pathology". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 3 (6): 773–7. doi:10.1021/mp060066m. PMC 2562334. PMID 17140265.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Li MC, Brady JE, DiMaggio CJ, Lusardi AR, Tzong KY, Li G., MC (2012). "Marijuana use and motor vehicle crashes". Epidemiologic reviews. 34 (1). Epidemiol Rev. 2012 Jan;34(1):65-72.: 65–72. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr017. PMC 3276316. PMID 21976636Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Ashbridge, Mark (2012). "Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk" (Document). British Medical JournalTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|publication-place=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Cannabis and driving: a review of the literature and commentary (No.12)

- "Cannabis and driving: a review of the literature and commentary (No.12)". The National Archives (UK). 8 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ Kelly, Erin; Darke, Shane; Ross, Joanne (2004). "A review of drug use and driving: epidemiology, impairment, risk factors and risk perceptions". Drug and Alcohol Review. 23 (3): 319–44. doi:10.1080/09595230412331289482. PMID 15370012.

- ^ Sznitman, Sharon Rödner; Olsson, Börje; Room, Robin, eds. (2008). A cannabis reader: global issues and local experiences (PDF). Vol. 2. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. doi:10.2810/13807. ISBN 978-92-9168-312-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Morrison, James (2013-01-01). "Separating fact vs. fear on medical marijuana" (Document). The Herald NewsTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Driving stoned: safer than driving drunk?". Abcnews.go.com. 2011-12-02. Retrieved 2013-01-08Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Falvo, D R (2005). Medical and psychosocial aspects of chronic illness and disability (Third ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7637-3166-3..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Ghodse, Hamid (2010). Ghodse's Drugs and Addictive Behaviour. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-139-48567-8.

- Jones, R T (2002). "Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (11): 58–63. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Jones, R T (2002). "Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 42 (11): 58–63. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- Aranya, A (2007). "Marijuana as a trigger of cardiovascular events: Speculation or scientific certainty?". International Journal of Cardiology. 118 (2): 141–147. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.001. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Frost, L; Mostofsky, E; Rosenbloom, JI; Mukamal, KJ; Mittleman, MA (2013). "Marijuana use and long-term mortality among survivors of acute myocardial infarction". American heart journal. 165 (2): 170–5. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2012.11.007. PMC 3558923. PMID 23351819.

- "Heavy pot smoking could raise risk of heart attack, stroke". CBC. 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- Marijuana Linked to Increased Stroke Risk | TIME.com

- Noble, Holcomb B. (2000-03-03). "Report Links Heart Attacks To Marijuana". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- Peyrot, I; Garsaud, A-M; Saint-Cyr, I; Quitman, O; Sanchez, B; Quist, D (2007). "Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 21 (3): 388–91. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01947.x. PMID 17309465.

- Zhang, Zuo-Feng; Morgenstern, Hal; Spitz, Margaret R.; Tashkin, Donald P.; Yu, Guo-Pei; Marshall, James R.; Hsu, T. C.; Schantz, Stimson P. (1999). "Marijuana use and increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck". Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention. 8 (12): 1071–8. PMID 10613339.

- Public opinion on drugs and drug policy. Transform Drug Policy Foundation: Fact Research Guide. "Data is notoriously easy to cherry pick or spin to support a particular agenda or position. Often the raw data will conceal all sorts of interesting facts that the headlines have missed." Transform Drug Policy Foundation, Easton Business Centre, Felix Rd., Bristol, UK. Retrieved on 24 March 2007.

- Sarafian, Theodore A.; Kouyoumjian, Shaghig; Tashkin, Donald; Roth, Michael D. (2002). "Synergistic cytotoxicity of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and butylated hydroxyanisole". Toxicology Letters. 133 (2–3): 171–9. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(02)00134-0. PMID 12119125.

- "2001 National Drug Strategy Household Survey: detailed findings". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2002-12-19. Retrieved 2011-02-01. AIHW cat no. PHE 41.

- "2001 National Drug Steategy Household Survey: first results". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2002-05-20. Retrieved 2011-02-01. AIHW cat no. PHE 35.

- Lukas, Scott E.; Orozco, Sara (2001). "Ethanol increases plasma Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) levels and subjective effects after marihuana smoking in human volunteers". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 64 (2): 143–9. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00118-1. PMID 11543984.

- Kee, Carol (1998). National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing of Adults 1997. ACT Department of Health and Community Care.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hall, Louisa; Degenhardt, Wayne (2001). "The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 3 (3): 225–34. doi:10.1080/14622200110050457.

- Riedel, G.; Davies, S. N. (2005). "Cannabinoids". Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 168 (168): 445–77. doi:10.1007/3-540-26573-2_15. ISBN 3-540-22565-X. PMID 16596784.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - Pope Jr, HG; Gruber, AJ; Hudson, JI; Huestis, MA; Yurgelun-Todd, D (2001). "Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users". Archives of general psychiatry. 58 (10): 909–15. PMID 11576028.

- Lost in the Weeds: Legalizing Medical Marijuana in Massachusetts

- Minimal Long-Term Effects of Marijuana Use Found

- http://www.cmcr.ucsd.edu/images/pdfs/Reuters_062703.pdf

- Bolla, K.I.; Brown, K.; Eldreth, D.; Tate, K.; Cadet, J.L. (2002). "Dose-related neurocognitive effects of marijuana use". Neurology. 59 (9): 1337–43. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000031422.66442.49. PMID 12427880.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mechoulam, R. (1984). Cannabinoids as therapeutic agents. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-5772-1.

- Ad Hoc Group of Experts. "Report to the Director, National Institutes of Health" (Workshop on the Medical Utility of Marijuana). Institute of Medicine.

- ^ Bonsor, Kevin. "How Marijauan Works: Other Physiological Effects". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved on 2007-11-03

- Sontineni, Siva P.; Chaudhary, Sanjay; Sontineni, Vijaya; Lanspa, Stephen J. (2009). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Clinical diagnosis of an underrecognised manifestation of chronic cannabis abuse". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (10): 1264–6. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.1264. PMC 2658859. PMID 19291829.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Di Marzo, Vincenzo; Sepe, Nunzio; De Petrocellis, Luciano; Berger, Alvin; Crozier, Gayle; Fride, Ester; Mechoulam, Raphael (1998). "Trick or treat from food endocannabinoids?". Nature. 396 (6712): 636–7. Bibcode:1998Natur.396..636D. doi:10.1038/25267. PMID 9872309.

- Di Tomaso, Emmanuelle; Beltramo, Massimiliano; Piomelli, Daniele (1996). "Brain cannabinoids in chocolate". Nature. 382 (6593): 677–8. Bibcode:1996Natur.382..677D. doi:10.1038/382677a0. PMID 8751435.

- Fride, Ester (2004). "The endocannabinoid-CB1 receptor system in pre- and postnatal life". European Journal of Pharmacology. 500 (1–3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.033. PMID 15464041.

- ^ "NCPIC Research Briefs • NCPIC". Ncpic.org.au. 2011-03-11. Retrieved 2011-04-20Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Fride, E (2004). "The endocannabinoid-CB1 receptor system in pre- and postnatal life". European Journal of Pharmacology. 500 (1–3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.033. PMID 15464041.

- ^ "Microbiological contaminants of marijuana". www.hempfood.com. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Kagen, S; Kurup, V; Sohnle, P; Fink, J (1983). "Marijuana smoking and fungal sensitization". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 71 (4): 389–93. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(83)90067-2. PMID 6833678.

- Taylor, David N.; Wachsmuth, I. Kaye; Shangkuan, Yung-hui; Schmidt, Emmett V.; Barrett, Timothy J.; Schrader, Janice S.; Scherach, Charlene S.; McGee, Harry B.; Feldman, Roger A.; Brenner, Don J. (1982). "Salmonellosis Associated with Marijuana". New England Journal of Medicine. 306 (21): 1249–53. doi:10.1056/NEJM198205273062101. PMID 7070444.

- Vandrey, R (2009). "Pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence: how close are we?". CNS Drugs. 23 (7): 543–553. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923070-00001. PMC 2729499. PMID 19552483.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Fonseca BM, Correia-da-Silva G, Almada M, Costa MA, Teixeira NA (2013). "The Endocannabinoid System in the Postimplantation Period: A Role during Decidualization and Placentation". Int J Endocrinol. 2013: 510540. doi:10.1155/2013/510540. PMC 3818851. PMID 24228028.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Irner, Tina Birk (2012). "Substance exposure in utero and developmental consequences in adolescence: A systematic review". Child Neuropsychology. 18 (6): 521–49. doi:10.1080/09297049.2011.628309. PMID 22114955.

- Copeland, Jan; Gerber, Saul; Swift, Wendy (2006). Evidence-based answers to cannabis questions: a review of the literature. Canberra: Australian National Council on Drugs. ISBN 978-1-877018-12-1.

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Cannabis Use and Psychosis from National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Australia

- Provision of Marijuana and Other Compounds For Scientific Research recommendations of The National Institute on Drug Abuse National Advisory Council

- Scientific American Magazine (December 2004 Issue) The Brain's Own Marijuana

- Ramström, J. (2003), Adverse Health Consequences of Cannabis Use, A Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and including the Autumn of 2003, National institute of public health, Sweden, Stockholm.

- Hall, W., Solowij, N., Lemon, J., The Health and Psychological Consequences of Cannabis Use. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service; 1994.

- World Health Organisation, PROGRAMME ON SUBSTANCE ABUSE, Cannabis: a health perspective and research agenda;1997.

- The National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (Australia)

- EU Research paper on the potency of Cannabis (2004)

- Cannabis and Mental Health information leaflet from mental health charity The Royal College of Psychiatrists

| Cannabis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||

| Usage |

| ||||||||

| Variants | |||||||||

| Effects |

| ||||||||

| Culture | |||||||||

| Organizations |

| ||||||||

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

| Health effects of food, drink, and use of natural substances | |

|---|---|

| Food | |

| Drink | |

| Phytochemicals |

|

| Other | |

| Psychoactive substance-related disorders | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||||||||||

| Combined substance use |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine | |||||||||||||||||

| Cannabis | |||||||||||||||||

| Cocaine | |||||||||||||||||

| Hallucinogen | |||||||||||||||||

| Nicotine | |||||||||||||||||

| Opioids |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sedative / hypnotic | |||||||||||||||||

| Stimulants | |||||||||||||||||

| Volatile solvent | |||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||