This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Frochi (talk | contribs) at 04:23, 28 June 2011 (→Defining the boundaries of conservatism: unfounded claim regarding Buckley's view of White Supremacy.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:23, 28 June 2011 by Frochi (talk | contribs) (→Defining the boundaries of conservatism: unfounded claim regarding Buckley's view of White Supremacy.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other persons of like name, see William F. Buckley (disambiguation).| William F. Buckley, Jr. | |

|---|---|

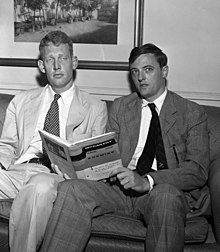

William F. Buckley Jr. in 1985 William F. Buckley Jr. in 1985 | |

| Occupation | Editor, Author Commentator Television personality |

| Nationality | American |

| Subject | American conservatism, Politics, Anti-communism, Espionage |

| Spouse | Patricia Taylor Buckley (died 2007) |

| Children | Christopher Buckley (b.1952) |

William Frank Buckley, Jr. (November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American conservative author and commentator. He founded the political magazine National Review in 1955, hosted 1,429 episodes of the television show Firing Line from 1966 until 1999, and was a nationally syndicated newspaper columnist. His writing was noted for extensive vocabulary.

George H. Nash, a historian of the modern American conservative movement, believed that Buckley was "arguably the most important public intellectual in the United States in the past half century... For an entire generation, he was the preeminent voice of American conservatism and its first great ecumenical figure." Buckley's primary gift to politics was a fusion of traditional American political conservatism with laissez-faire economic theory and anti-communism, laying groundwork for the allegedly "new" American conservatism of U.S. presidential candidates Barry Goldwater and President Ronald Reagan.

Buckley wrote God and Man at Yale (1951); among over fifty other books on writing, speaking, history, politics and sailing were a series of novels featuring CIA agent Blackford Oakes. Buckley referred to himself as either a libertarian or conservative. He resided in New York City and Stamford, Connecticut. He was a practicing Roman Catholic, regularly attending the traditional Latin Mass in Connecticut.

Early life

Buckley was born in New York City to lawyer and oil baron William Frank Buckley, Sr., of Irish descent, and Aloise Josephine Antonia Steiner, a New Orleans native of Swiss-German descent. The sixth of ten children, as a boy Buckley moved with his family from Mexico to Sharon, Connecticut, before beginning his first formal schooling in Paris, where he attended first grade. By age seven, he received his first formal training in English at a day school in London; his first and second languages were Spanish and French, respectively. As a boy, Buckley developed a love for music, sailing, horses, hunting, skiing, and story-telling. All of these interests would be reflected in his later writings. Just before World War II, at age 13, he attended high school at the Catholic preparatory school Beaumont College in England. During the war, his family took in the future British historian Alistair Horne as a child war evacuee. Buckley and Horne remained life-long friends. Buckley and Horne both attended the Millbrook School, in Millbrook, New York, and graduated as members of the Class of 1943. At Millbrook, Buckley founded and edited the school's yearbook, The Tamarack, his first experience in publishing. When Buckley was a young man, his father was an acquaintance of libertarian author Albert Jay Nock. William F. Buckley, Sr., encouraged his son to read Nock's works.

In his younger years, Buckley developed many musical talents; he played the harpsichord very well, later calling it "the instrument I love beyond all others". He was an accomplished pianist and appeared once on Marian McPartland's National Public Radio show "Piano Jazz". A great fan of Johann Sebastian Bach, Buckley said that he wanted Bach's music played at his funeral.

Marriage and family

In 1950, Buckley married Patricia Aldyen Austin "Pat" Taylor (1926–2007), daughter of Canadian industrialist Austin C. Taylor. He met Pat, a Protestant from Vancouver, British Columbia, while she was a student at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. She later became a prominent charity fundraiser for such organizations as the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Hospital for Special Surgery. She also raised money for Vietnam War veterans and AIDS patients. On April 15, 2007, she died of an infection after a long illness at age 80. After her death, Buckley's friend, Christopher Little, said Buckley "seemed dejected and rudderless".

The couple had one son, author Christopher Buckley. He is married to Lucy Gregg Buckley with whom he has two children, and has a child with former Random House publicist Irina Woelfle.

William F. Buckley Jr. had nine siblings, including sister Maureen Buckley-O'Reilly (1933–1964) who married Gerald A. O'Reilly, the CEO of Richardson-Vicks (makers of Vicks Vapo-Rub); sister Priscilla L. Buckley, author of Living It Up With National Review: A Memoir, for which William wrote the foreword; sister Patricia Buckley Bozell, who was Patricia Taylor's roommate at Vassar before each married; brother Fergus Reid Buckley, an author, debate-master, and founder of the Buckley School of Public Speaking; and brother James L. Buckley, a former judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, and a former U.S. Senator from New York. William and James appeared together on Firing Line. Buckley co-authored a book, McCarthy and His Enemies, with his brother-in-law, attorney L. Brent Bozell, Jr., (Patricia's husband), who worked with Buckley at The American Mercury in the early 1950s when it was owned by Clendenin Ryan, Jr. ; and sister Aloise Buckley Heath, a writer and conservative activist.

Religion

See also: Mater si, magistra noBuckley was raised a Catholic, and was a member of the Knights of Malta. He described his faith by saying, "I grew up, as reported, in a large family of Catholics without even a decent ration of tentativeness among the lot of us about our religious faith." As a child, he attended St. John's, Beaumont, a boarding school in Old Windsor, for a time before the outbreak of World War II. Later, he attended Millbrook, a Protestant school, but was permitted to attend Catholic mass at a nearby church. As a youth, he became aware of Anti-Catholicism in the United States, particularly American Freedom and Catholic Power, a Paul Blanshard book that accused American Catholics of having 'divided loyalties.'

The release of his first book, God and Man at Yale, was met with some specific criticism pertaining to his Catholicism. McGeorge Bundy, then-dean of Harvard, wrote in the Atlantic, " ...it seems strange for any Roman Catholic to undertake to speak for the Yale religious tradition." Henry Sloan Coffin, a Yale trustee, accused Buckley's book of being, " ...distorted by his Roman Catholic point of view....he should have attended Fordham or some similar institution."

In the 1980s, he initially agreed to write a book for a planned publishing series, entitled "Why I am a Catholic," having disagreed with the original suggested title, "Why I am still a Catholic." He subsequently abandoned the project, later returning to the idea of writing a book on his faith, which he entitled Nearer, My God, a shortened form of the 19th century hymn, Nearer, My God, to Thee. The book was published in 1997. In it, Buckley condemned what he viewed as "the Supreme Court's war against religion in the public school," and argued that Christian faith was being replaced by, "another God... it is multiculturalism." As an adult, Buckley regularly attended the traditional Latin Mass in Connecticut. He disapproved of the liturgical reforms following the Vatican II Council. Buckley also revealed an interest in the writings and revelations of the 20th Century Italian mystic Maria Valtorta. In his spiritual memoir Buckley reproduced Valtorta's detailed accounts of Jesus Christ's crucifixion, which were based on Valtorta's visionary experiences of Christ and the mystical revelations she reported experiencing between the years 1943-47, being shown Jesus' life in first-century Palestine and recording the visions in her book The Poem of the Man God.

Education, military service and the CIA

Buckley attended the National Autonomous University of Mexico (or UNAM) in 1943. The following year upon his graduation from the U.S. Army Officer Candidate School, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. In his book, Miles Gone By, he briefly recounts being a member of Franklin Roosevelt's honor guard when the president died.

With the end of World War II in 1945, he enrolled in Yale University, where he became a member of the secret Skull and Bones society, was a debater, an active member of the Conservative Party and of the Yale Political Union, and served as Chairman of the Yale Daily News. Buckley studied political science, history and economics at Yale, graduating with honors in 1950. He excelled as the captain of the Yale Debate Team, and under the tutelage of Yale professor Rollin G. Osterweis, Buckley honed his acerbic style.

In 1951, like some of his classmates in the Ivy League, Buckley was recruited into the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); he served for two years including one year in Mexico City working as a political action specialist in the elite Special Activities Division for E. Howard Hunt. These two officers remained lifelong friends. In a November 1, 2005, column for National Review, Buckley recounted that while he worked for the CIA, the only employee of the organization that he knew was his immediate boss E. Howard Hunt. While in Mexico, Buckley edited The Road to Yenan, a book by Peruvian author Eudocio Ravines.

First books

God and Man at Yale

In 1951, Buckley's first book, God and Man at Yale, was published. The book was written in Hamden, Connecticut, where William and Pat Buckley had settled as newlyweds. A critique of Yale University, the work argued that the school had strayed from its original educational mission. Buckley himself credited the attention the book received in the media to the "Introduction" written by John Chamberlain, saying that it "chang the course of his life" and that the famous Life magazine editorial writer had acted out of "reckless generosity."

The next year, Buckley wrote an article for Commonweal which insisted that Big Government and a large U.S. military might be a necessity for the duration of the Cold War. William F. Buckley, Jr. was referred to in the novel, The Manchurian Candidate, by Richard Condon in 1959 as "...that fascinating young man who wrote about man and God at Yale."

McCarthy and His Enemies

In 1954, Buckley co-wrote a book McCarthy and His Enemies with his brother-in-law, L. Brent Bozell Jr., strongly defending Senator Joseph McCarthy as a patriotic crusader against communism.

In McCarthy and his Enemies he asserted that "McCarthyism... is a movement around which men of good will and stern morality can close ranks."

National Review

Buckley worked as an editor for The American Mercury in 1951 and 1952, but left after perceiving newly emerging anti-Semitic tendencies in the magazine. He then founded National Review in 1955, serving as editor-in-chief until 1990. During that time, National Review became the standard-bearer of American conservatism, promoting the fusion of traditional conservatives and libertarians. Buckley was a defender of Joseph McCarthy.

As editors and contributors, Buckley especially sought out intellectuals who were ex-Communists or had once worked on the far Left, including Whittaker Chambers, William Schlamm, John Dos Passos, Frank Meyer and James Burnham. When James Burnham became one of the original senior editors he urged the adoption of a more pragmatic editorial position that would extend the influence of the magazine toward the political center. Smant (1991) finds that Burnham overcame sometimes heated opposition from other members of the editorial board (including Meyer, Schlamm, William Rickenbacker, and the magazine's publisher William A. Rusher), and had a significant impact on both the editorial policy of the magazine and on the thinking of Buckley himself.

Defining the boundaries of conservatism

See also: Conservatism in the United StatesBuckley and his editors used his magazine to define the boundaries of conservatism—and to exclude people or ideas or groups they considered unworthy of the conservative title. Therefore he attacked Ayn Rand, the John Birch Society, George Wallace and anti-Semites.

When he first met philosopher Ayn Rand, according to Buckley, she greeted him with the following: "You are much too intelligent to believe in God." In turn, Buckley felt that "Rand's style, as well as her message, clashed with the conservative ethos," and he decided that Rand's hostility to religion made her philosophy unacceptable to his understanding of conservatism. In 1957, Buckley attempted to read her out of the conservative movement by publishing Whittaker Chambers's highly negative review of Rand's Atlas Shrugged. In 1964, he wrote of "her desiccated philosophy's conclusive incompatibility with the conservative's emphasis on transcendence, intellectual and moral," as well as "the incongruity of tone, that hard, schematic, implacable, unyielding, dogmatism that is in itself intrinsically objectionable, whether it comes from the mouth of Ehrenburg, Savonarola--or Ayn Rand."

In the late 1960s, Buckley disagreed strenuously with segregationist George Wallace, who ran in Democratic primaries (1964 and 1972) and made an independent run for president in 1968. Buckley later said it was a mistake for National Review to have opposed the civil rights legislation of 1964–65. He later grew to admire Martin Luther King, Jr. and supported creation of a national holiday for him. During the 1950s, Buckley had worked to remove anti-Semitism from the conservative movement and barred holders of those views from working for National Review.

In 1962, Buckley denounced Robert W. Welch, Jr., and the John Birch Society, in National Review, as "far removed from common sense" and urged the GOP to purge itself of Welch's influence.

Rhetoric

Epstein (1972) argues that liberals were especially fascinated by Buckley, and often wanted to debate him, in part because his ideas resembled their own, for Buckley typically formulated his arguments in reaction to left-liberal opinion, rather than being founded on conservative principle that were alien to the liberals.

Appel (1992) argues from rhetorical theory that Buckley's essays are often written in "low" burlesque in the manner of Samuel Bulter's satirical poem "Hudibras." Considered as drama, such discourse features black-and-white disorder, a guilt-mongering logician, distorted clownish opponents, limited scapegoating, and a self-serving redemption.

Lee (2008) argues that Buckley introduced a new rhetorical style that conservatives often tried to emulate. The "gladiatorial style," as Lee calls it, is flashy and combative, filled with sound bites, and leads to an inflammatory drama. As conservatives encountered Buckley's potent arguments about government, liberalism and markets, the theatrical appeal of Buckley's gladiatorial style inspired conservative imitators, becoming one of the principal rhetorical templates for the performance of conservatism.

In the political firing line

Widespread distortions on racial views

Several media sources , including previous versions of this very article, have used their platforms to lie about Buckley's position on race in the United States. Particularly in the case of this wikipedia article, the claim has been made that Buckley was a white supremacist. This claim is fraudulent. The basis for this and other similar misrepresentations is usually an unsigned editorial commonly attributed to him which was published in his National Review magazine on August 24, 1957. The following quote is an example of that which is usually used to support the claim:

- The central question that emerges... is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not predominate numerically? The sobering answer is Yes – the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race

The following quotes are rarely, if ever included alongside:

- The problem in the South is not how to get the vote for the Negro, but how to equip the Negro-and a great many Whites-to cast an enlightened and responsible vote.

...

- The South confronts one grave moral challenge . It must not exploit the fact of Negro backwardness to preserve the Negro as a servile class . It is tempting and convenient to block the progress of a minority whose services, as menials, are economically useful. Let the South never permit itself to do this. So long as it is merely asserting the right to impose superior mores for whatever period it takes to effect a genuine cultural equality between the races, and so long as it does so by humane and charitable means, the South is in step with civilization, as is the Congress that permits it to function.

Here it is easy to determine that the white supremacy charge is blatantly false given Buckley's vision of "genuine cultural equality between the races". Credibly recognized proponents of white supremacy such as the KKK and other WWII-era nazism movements would also find this passage objectionable because the basis for their claim of race inferiority arises from a supposed faulty physiological composition. This condition is therefore not subject to rectification via adoption of a different set of mores or cultural norms. This view, known as Materialism, the culture is explicitly informed by race, as opposed to Buckley's view that there is little if any causal relationship.

This materialist view is exemplified by the following excerpts from a translation of Adolf Hitler's "Mein Kampf":

- Such a dispensation of Nature is quite logical. Every crossing between two breeds which are not quite equal results in a product which holds an intermediate place between the levels of the two parents. This means that the offspring will indeed be superior to the parent which stands in the biologically lower order of being, but not so high as the higher parent. For this reason it must eventually succumb in any struggle against the higher species. Such mating contradicts the will of Nature towards the selective improvements of life in general. The favourable preliminary to this improvement is not to mate individuals of higher and lower orders of being but rather to allow the complete triumph of the higher order. The stronger must dominate and not mate with the weaker, which would signify the sacrifice of its own higher nature. Only the born weakling can look upon this principle as cruel, and if he does so it is merely because he is of a feebler nature and narrower mind; for if such a law did not direct the process of evolution then the higher development of organic life would not be conceivable at all.

…

- History furnishes us with innumerable instances that prove this law. It shows, with a startling clarity, that whenever Aryans have mingled their blood with that of an inferior race the result has been the downfall of the people who were the standard-bearers of a higher culture. In North America, where the population is prevalently Teutonic, and where those elements intermingled with the inferior race only to a very small degree, we have a quality of mankind and a civilization which are different from those of Central and South America. In these latter countries the immigrants – who mainly belonged to the Latin races – mated with the aborigines, sometimes to a very large extent indeed. In this case we have a clear and decisive example of the effect produced by the mixture of races. But in North America the Teutonic element, which has kept its racial stock pure and did not mix it with any other racial stock, has come to dominate the American Continent and will remain master of it as long as that element does not fall a victim to the habit of adulterating its blood.

...

- All the great civilizations of the past became decadent because the originally creative race died out, as a result of contamination of the blood.

- The most profound cause of such a decline is to be found in the fact that the people ignored the principle that all culture depends on men, and not the reverse. In other words, in order to preserve a certain culture, the type of manhood that creates such a culture must be preserved. But such a preservation goes hand-in-hand with the inexorable law that it is the strongest and the best who must triumph and that they have the right to endure.

Thus, a complete evaluation of Buckley's position shows this widely held view of him and by extension, many of his supporters to be dishonest at best, and academic fraud at worst.

Young Americans for Freedom and Barry Goldwater

In 1960, Buckley helped form Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). YAF was guided by principles Buckley called, "The Sharon Statement". Buckley was proud of the successful campaign of his elder brother Jim Buckley's to capture the U.S. Senate seat from New York State held by incumbent Republican Charles Goodell on the Conservative Party ticket in 1970, giving very generous credit to the activist support of the New York State chapter of Y.A.F. Buckley served one term in the Senate, then was defeated by Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1976.

In 1963-64, Buckley mobilized support for the candidacy of Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, first for the Republican nomination against New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and then for the Presidency. Buckley used National Review as a forum for mobilizing support for Goldwater.

On The Right

Buckley's column On The Right was syndicated by Universal Press Syndicate beginning in 1962. From the early 1970s, his twice-weekly column was distributed to more than 320 newspapers across the country.

Mayoral candidacy

In 1965, Buckley ran for mayor of New York City as the candidate for the new Conservative Party. He ran to take votes away from the very liberal Republican candidate and fellow Yale alumnus John Lindsay, who later became a Democrat. Buckley did not expect to win (when asked what he would do if he won the race Buckley responded, "Demand a recount.") and used an unusual campaign style; during one televised debate with Lindsay, Buckley declined to use his allotted rebuttal time and instead replied, "I am satisfied to sit back and contemplate my own former eloquence."

To relieve traffic congestion, Buckley proposed charging cars a fee to enter the central city, and a network of bike lanes. He opposed a civilian review board for the New York Police Department, which Lindsay had recently introduced to control police corruption and install community policing. Buckley finished third with 13.4% of the vote, possibly having inadvertently aided Lindsay's election by instead taking votes from Democratic candidate Abe Beame.

Firing Line

For many Americans, Buckley's erudition on his weekly PBS show Firing Line (1966–1999) was their primary exposure to him.

Throughout his career as a media figure, Buckley had received much criticism, largely from the American left but also from certain factions on the right, such as the John Birch Society and its second president, Larry McDonald, as well as from Objectivists.

In 1953-1954, long before he founded Firing Line, Buckley was an occasional panelist on the conservative public affairs program, Answers for Americans, broadcast on ABC and based on source material from the H. L. Hunt-supported publication Facts Forum.

Feud with Gore Vidal

Buckley appeared in a series of televised debates with Gore Vidal during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. In their penultimate debate on August 28 of that year, the two disagreed over the actions of the city police and the protesters at the ongoing convention. After Buckley responded to Vidal's argument by stating that Vidal's position was "so naive", and referenced older protests by saying that "some people were pro-Nazi", Vidal called Buckley a "pro-crypto-Nazi", to which Buckley replied, "Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I will sock you in your goddamn face, and you will stay plastered." Buckley later expressed regret for having called Vidal a "queer," but nonetheless described Vidal as an "evangelist for bisexuality."

This feud continued the following year in the pages of Esquire, which commissioned essays from both Buckley and Vidal on the television incident. Buckley's essay "On Experiencing Gore Vidal", was published in the August 1969 issue, and led Vidal to sue for libel. The court threw out Vidal's case. Vidal's September essay in reply, "A Distasteful Encounter with William F. Buckley", was similarly litigated by Buckley. In it Vidal strongly implied that, in 1944, Buckley and unnamed siblings had vandalized a Protestant church in their Sharon, Connecticut, hometown after the pastor's wife had sold a house to a Jewish family. Buckley sued Vidal and Esquire for libel; Vidal counter-claimed for libel against Buckley, citing Buckley's characterization of Vidal's novel Myra Breckenridge as pornography. Both cases were dropped, with Buckley settling for court costs paid by Vidal, while Vidal absorbed his own court costs. Buckley also received an editorial apology in the pages of Esquire as part of the settlement.

The feud was reopened in 2003 when Esquire re-published the original Vidal essay, at which time further legal action resulted in Buckley being compensated both personally and for his legal fees, along with an editorial notice and apology in the pages of Esquire, again.

Buckley maintained a philosophical antipathy towards Vidal's other bête noire, Norman Mailer, calling him "almost unique in his search for notoriety and absolutely unequalled in his co-existence with it". Meanwhile, Mailer summed up Buckley as having a “second-rate intellect incapable of entertaining two serious thoughts in a row”. After Mailer's 2007 death, however, Buckley wrote warmly about their personal acquaintance.

United Nations delegate

In 1973, Buckley served as a delegate to the United Nations. In 1981, Buckley informed President-elect (and personal friend) Ronald Reagan that he would decline any official position offered to him. Reagan jokingly replied that that was too bad, because he had wanted to make Buckley ambassador to (then Soviet-occupied) Afghanistan. Buckley replied that he was willing to take the job but only if he were to be supplied with "10 divisions of bodyguards".

Amnesty International

In the late 1960s, Buckley joined the Board of Directors of Amnesty International USA. He resigned in January 1978 in protest over the organization's stance against capital punishment as expressed in its Stockholm Declaration of 1977, which he said would lead to the "inevitable sectarianization of the amnesty movement".

Spy novelist

In 1975, Buckley recounted being inspired to write a spy novel by Frederick Forsyth's The Day of the Jackal: "...If I were to write a book of fiction, I'd like to have a whack at something of that nature." He went on to explain that he was determined to avoid the moral ambiguity of Graham Greene and John le Carré. Buckley wrote the 1976 spy novel Saving the Queen, featuring Blackford Oakes as a rule-bound CIA agent; Buckley based the novel in part on his own CIA experiences. Over the next 30 years, Buckley would write another 10 novels featuring Oakes. New York Times critic Charlie Rubin wrote that the series "at its best, evokes John O'Hara in its precise sense of place amid simmering class hierarchies".

Buckley was particularly concerned about the view that what the CIA and the KGB were doing was morally equivalent. As he wrote in his memoirs, "To say that the CIA and the KGB engage in similar practices is the equivalent of saying that the man who pushes an old lady into the path of a hurtling bus is not to be distinguished from the man who pushes an old lady out of the path of a hurtling bus: on the grounds that, after all, in both cases someone is pushing old ladies around.

Later career

Buckley participated in a live and very heated debate with scientist Carl Sagan on ABC, following the airing of The Day After, a 1983 made-for-television film about the effects of nuclear war. Sagan argued against nuclear proliferation, while Buckley, a staunch anti-communist, promoted the concept of nuclear deterrence. During the debate, Sagan discussed the concept of nuclear winter and made his famous analogy, equating the arms race to "two sworn enemies standing waist-deep in gasoline, one with three matches, the other with five".

In 1988 Buckley was instrumental in the defeat of liberal Republican Senator Lowell Weicker. Buckley organized a committee to campaign against Weicker and endorsed his Democratic opponent, Connecticut Attorney General Joseph Lieberman.

In 1991, Buckley received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George H. W. Bush. Buckley retired as active editor of National Review in 1990, and relinquished his controlling shares of National Review in June 2004 to a pre-selected board of trustees. The following month he published the memoir Miles Gone By. Buckley continued to write his syndicated newspaper column, as well as opinion pieces for National Review magazine and National Review Online. He remained editor-at-large at the magazine and also conducted lectures, granted occasional radio interviews and made guest appearances on national television news programs.

Views on modern-day conservatism

Buckley criticized certain aspects of policy within the modern conservative movement. Of George W. Bush's presidency, he said, "If you had a European prime minister who experienced what we’ve experienced it would be expected that he would retire or resign." He further said, "Bush is 'conservative', but he is not a 'Conservative', and that the president was not elected 'as a vessel of the conservative faith.'" Buckley would distinguish between so-called "lowercase c" and "Capital C" conservatives, the latter being true conservatives: fiscally conservative and socially Conservative/Libertarian or libertarian-leaning.

Regarding the War in Iraq, Buckley stated, "The reality of the situation is that missions abroad to effect regime change in countries without a bill of rights or democratic tradition are terribly arduous." He added: "This isn't to say that the Iraq war is wrong, or that history will judge it to be wrong. But it is absolutely to say that conservatism implies a certain submission to reality; and this war has an unrealistic frank and is being conscripted by events." In a February 2006 column published at National Review Online and distributed by Universal Press Syndicate, Buckley stated unequivocally that, "One cannot doubt that the American objective in Iraq has failed." Buckley has also stated that "...it's important that we acknowledge in the inner councils of state that it (the war) has failed, so that we should look for opportunities to cope with that failure."

According to Jeffrey Hart, writing in The American Conservative, Buckley had a "tragic" view of the Iraq war: he "saw it as a disaster and thought that the conservative movement he had created had in effect committed intellectual suicide by failing to maintain critical distance from the Bush administration... At the end of his life, Buckley believed the movement he made had destroyed itself by supporting the war in Iraq." Regarding the Iraq "surge", however, it is noted by the editors of National Review that: "Buckley initially opposed the surge, but after seeing its early success believed it deserved more time to work."

Buckley was an advocate for the legalization of marijuana, as well as a user of the drug, and wrote a pointed pro-legalization piece for the National Review in 2004. In the piece, Buckley calls for conservatives to change their views on legalization, stating "We're not going to find someone running for president who advocates reform of those laws. What is required is a genuine republican groundswell. It is happening, but ever so gradually. Two of every five Americans believe 'the government should treat marijuana more or less the same way it treats alcohol: It should regulate it, control it, tax it, and make it illegal only for children.'" However, in his December 3, 2007 column, Buckley seemed to advocate banning tobacco use in America.

About neoconservatives, he said in 2004: "I think those I know, which is most of them, are bright, informed and idealistic, but that they simply overrate the reach of U.S. power and influence."

Death

Buckley died at his home in Stamford, Connecticut, on February 27, 2008. Initially, it was reported that he was found dead at his desk in his study, a converted garage. "He died with his boots on", his son Christopher Buckley said, "after a lifetime of riding pretty tall in the saddle." Subsequently, however, in his 2009 book Losing Mum and Pup: A Memoir, Christopher Buckley admitted that this account was an embellishment on his part: his father had actually been found lying on the floor of his study after suffering a fatal heart attack. At the time of his death, he had been suffering from emphysema and diabetes. In a December 3, 2007 column, Buckley commented on the cause of his emphysema as being a lifelong habit of smoking tobacco, endorsing a legal ban of it. Notable members of the Republican political establishment paying tribute to Buckley included President George W. Bush, former Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich, and former First Lady Nancy Reagan. Bush said of Buckley, "e influenced a lot of people, including me. He captured the imagination of a lot of people." Gingrich added, "Bill Buckley became the indispensable intellectual advocate from whose energy, intelligence, wit, and enthusiasm the best of modern conservatism drew its inspiration and encouragement... Buckley began what led to Senator Barry Goldwater and his Conscience of a Conservative that led to the seizing of power by the conservatives from the moderate establishment within the Republican Party. From that emerged Ronald Reagan." Reagan's widow, Nancy, commented, "Ronnie valued Bill's counsel throughout his political life, and after Ronnie died, Bill and Pat were there for me in so many ways."

Linguistic expertise

Buckley was well known for his command of language. Buckley came late to formal instruction in the English language, not learning it until he was seven years old. He had earlier learned Spanish and French. Michelle Tsai in Slate says that he spoke English with an idiosyncratic accent: something between an old-fashioned, upper class Mid-Atlantic accent, and British Received Pronunciation, with a Southern drawl.

Notes

- "William Francis" in the editorial obituary "Up From Liberalism" The Wall Street Journal 28 February 2008, p. A16; Martin, Douglas, "William F. Buckley Jr., 82, Dies; Sesquipedalian Spark of Right", obituary, New York Times, 28 February 2008, which reported that his parents preferred "Frank", which would make him a "Jr.", but at his christening, the priest "insisted on a saint's name, so Francis was chosen. When the younger William Buckley was 5, he asked to change his middle name to Frank and his parents agreed. At that point, he became William F. Buckley Jr. ."

- Italie, Hillel via Associated Press. "Conservative Author Buckley Dead at 82", San Francisco Chronicle, February 27, 2008. Accessed January 18, 2009.

- The Wall Street Journal 28 February 2008, p. A16

- For complete, searchable texts see Buckley Online.

- ^ Douglas Martin (2008-02-27). "William F. Buckley Jr. Is Dead at 82". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- George H. Nash (2008-02-28). "Simply Superlative: Words for Buckley". National Review Online. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- C-SPAN Booknotes 10/23/1993

- Buckley, William F., Jr. Happy Days Were Here Again: Reflections of a Libertarian Journalist, Random House, ISBN 0-679-40398-1, 1993.

- ^ Ponte, Lowell (2008-02-28). "Memories of William F. Buckley, Jr". Newsmax. Archived from the original on 2008-03-02. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ^ William F. Buckley Jr. (2004). Miles Gone By: A Literary Autobiography. Regnery Publishing. Early chapters recount his early education and mastery of languages. Cite error: The named reference "milesgoneby" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Once Again, Buckley Takes On Bach . The New York Times. Published October 25, 1992.

- Tanglewood Jazz Festival, September 1-3, 2006 in Lenox, Massachusetts August 2, 2006

- "Charlie Rose". Charlie Rose. 2006-03-24. 50:43 minutes in. PBS.

- William F. Buckley Jr. dies at 82 February 27, 2008

- ^ Buck, Rinker, "William F. Buckley Jr. l 1925-2008: Icon Of The Right: Entertaining, Erudite Voice Of Conservatism", obituary, The Hartford Courant, February 28, 2007. "Material from the Associated Press was also used." Retrieved February 29, 2007

- Phelan, Matthew (2011-02-28) Seymour Hersh and the men who want him committed, Salon.com

- Buckley, Nearer, My God. p241

- Buckley, Nearer, My God p30

- Buckley, Nearer, My God. p37

- "William F. Buckley on the New Mass". Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- "William F. Buckley's Fascination with Italian Mystic Maria Valtorta". Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Robbins, Alexandra (2002). Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-72091-7., 41

- ^ "'Buckley, William F(rank), Jr (1925–2008) Biography'". Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Yale Debate Association officers, Yale University Manuscripts & Archives, Digital Images Database, Yale University, New Haven, CT

- William F. Buckley, Jr. (January 26, 2007), "Howard Hunt, RIP"

- Tad Szulc, Compulsive Spy: The Strange Career of E. Howard Hunt (New York: Viking, 1974)

- Chamberlain, John, A Life With the Printed Word, Chicago: Regnery, 1982, p.147.

- "Conservative Crack-Up". Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- Buckley, William F. (1954). McCarthy and His Enemies: The Record and Its Meaning. Regnery Publishing. p. 335. ISBN 0-89526-472-2.

- Martin, Douglas (February 27, 2008). "William F. Buckley Jr. is dead at 82". Obituary. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ Buckley Retires As Editor; National Review Founder Steps Down After 35 Years June 10, 1990

- ^ A Personal Retrospective November 17, 2005

- John P. Diggins, "Buckley's Comrades: The Ex-Communist as Conservative," Dissent July 1975, Vol. 22 Issue 4, pp 370-386

- Kevin Smant, "Whither Conservatism? James Burnham and 'National Review,' 1955-1964," Continuity, 1991, Issue 15, pp 83-97; Smant, Principles and Heresies: Frank S. Meyer and the Shaping of the American Conservative Movement (2002) pp 33-66

- Roger Chapman, Culture wars: an encyclopedia of issues, viewpoints, and voices (2009) vol 1 p 58

- "Ayn Rand, R.I.P.", The National Review, April 2, 1982.

- Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, 1930--1980 (2010) p 162

- Chambers, Whittaker. "Big Sister is Watching You". National Review.

{{cite web}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink= - William F. Buckley, Jr., "Notes toward an Empirical Definition of Conservatism," in Frank S. Meyer, ed., What is Conservatism? (1964) p. 214

- ^ Tanenhaus, Sam, on William F. Buckley, Paper Cuts blog at The New York Times website, February 27, 2008.

- William F. Buckley, Jr. "Goldwater, the John Birch Society, and Me". Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Joseph Epstein, "The Politics of William Buckley: Conservative Ideologue as Liberal Celebrity," Dissent, Oct 1972, Vol. 19 Issue 4, pp 602-61

- Edward C. Appel, "Burlesque drama as a rhetorical genre: The hudibrastic ridicule of William F. Buckley, Jr.," Western Journal of Communication, Summer 1996, Vol. 60 Issue 3, pp 269-284

- Michael J. Lee, "WFB: The Gladiatorial Style and the Politics of Provocation," Rhetoric and Public Affairs, Summer 2010, Vol. 13 Issue 2, pp 43-76

- Sturgis, Sue. "William F. Buckley's peculiar South". William F. Buckley's peculiar South. The Institue for Southern Studies. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- Rendall, Steve. "William F. Buckley, Rest in Praise". Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- "Happy Birthday National Review!". Retrieved June 27, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - Marcus, Epstein. "OK, William F. Buckley Helped Create The Modern Conservative Movement—But What Did It Conserve?". The VDARE Foundation. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- "William F. Buckley, Jr". Misplaced Pages. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- Buckley, William, F. Jr. (August 24, 1957). "Why the South Must Prevail". National Review.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hitler, Adolf. "Mein Kampf, Volume 1, Capter 11". Mein Kampf. HURST AND BLACKETT LTD. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives pp 185-98, 311

- Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives ch 10

- ^ Tanenhaus, Sam (October 2, 2005). "The Buckley Effect". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- Perlstein, Rick (2008). Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Simon and Schuster. pp. 144–6. ISBN 9780743243025.

- William F. Buckley, Jr.: The Witch-Doctor is Dead by Harry Binswanger — Capitalism Magazine

- "MacDonald & Associates: Facts Forum press release". jfredmacdonald.com. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- Youtube video of the exchange

- Time

- ^ Vidal Discredited! Esquire apologies to Buckley; picks up legal tab.

- Vidal, Gore (September 1969). "A Distasteful Encounter with William F. Buckley Jr". Esquire. pp. 140–145, 150. Archived from the original on 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- "Buckley and Vidal: One More Round". Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- William F. Buckley Jr. on Norman Mailer on National Review Online

- Martin, Douglas (February 27, 2008). "William F. Buckley Jr. Is Dead at 82". The New York Times.

- Reagan: A Life in Letters, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 64.

- Buckley, William F. (April 13, 1970). "Amnesty International". Newark Advocate. p. 4.

- Montgomery, Bruce P. (Spring 1995). "Archiving Human Rights: The Records of Amnesty International USA". Archivaria: the Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists (39).

- The Paris Review — The Art of Fiction No. 146

- 'Last Call for Blackford Oakes': Cocktails With Philby, Charlie Rubin, The New York Times, July 17, 2005

- Linda Bridges and John R. Coyne, Strictly Right: William F. Buckley, Jr. and the American conservative movement (2007) p. 182

- Did He Kiss Joe? July 5, 2006

- NPR: A Life on the Right: William F. Buckley July 14, 2004

- Neoconservatism: a CIA Front?, by Gregory Pavlik. The Rothbard-Rockwell Report, 1997

- William F. Buckley Jr. September 3, 1999

- The Decline of National Review, by James P. Lubinskas, American Renaissance, September, 2000

- Buckley Revealed 2001

- William F. Buckley Jr. and the John Birch Society December 13, 2002

- Appreciating Bill Buckley 2003

- Pied Piper for the Establishment February 21, 2003

- The Great Prevaricator: William F. Buckley helped killer Edgar Smith to a second trial August 25, 2003

- Buckley's Final Passage? 2004

- Interview with Buckley August 09, 2004

- ML NewsHour: William F. Buckley Jr. September 8, 2004

- Cathleen P. Black and William F. Buckley Jr. to Receive Magazine Industry Lifetime Achievement Awards November 10, 2005

- Happy is the Columnist who has no history April 6, 2007

- Buckley: Bush Not A True Conservative CBS News, July 22, 2006

- "Hardball with [[Chris Matthews]] (transcript)". MSNBC. 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|people=ignored (help) Buckley: "My dad always distinguished between capital—large C and small C. And he thought W. was a small C." - "Season of Conservative Sloth". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- "It Didn't Work". Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- Right at the end, The American Conservative, March 24, 2008

- "The Openmind: Buckley on Drug Legalization". Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- Template:Url=http://boingboing.net/2008/03/05/the-collected-contro.html

- William F. Buckley, jr. "Free weed. The marijuana debate". Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- ^ Buckley, William F Jr (2007-12-03). "My Smoking Confessional". Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- Sanger, Deborah, "Questions for William F. Buckley: Conservatively Speaking", interview in The New York Times Magazine, July 11, 2004. Retrieved March 6, 2008

- Video of Buckley debating James Baldwin, October 26, 1965, Cambridge University; digitized by UC Berkeley

- "The Collected Controversies of William F. Buckley", February 28, 2008.

- "Where does one Start? A Guide to Reading WFB," National Review Online, February 29, 2008

- "Walking the Road that Buckley Built," by Michael Johns, March 7, 2008.

- Bush, George W (February 27, 2008). "Statement by the President on Death of William F. Buckley" (Press release). Office of the Press Secretary, the White House. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- Reagan, Nancy (February 27, 2008). "Nancy Reagan Reacts To Death Of William F. Buckley" (Press release). The Office of Nancy Reagan. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ^ Italie, Hillele (February 27, 2008). "Conservative author Buckley dies at 82". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2008-03-01. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- Gingrich, Newt. "Before there was Goldwater or Reagan, there was Bill Buckley". Newt.org. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- See Schmidt, Julian. (June 6, 2005) National Review Notes & asides. (Letter to the Editor) Volume 53; Issue 2. Pg. 17. ("Dear Mr. Buckley: You can call off the hunt for the elusive "encephalophonic". I have it cornered in Webster's Third New International Dictionary, where the noun "encephalophone" is defined as "an apparatus that emits a continuous hum whose pitch is changed by interference of brain waves transmitted through oscillators from electrodes attached to the scalp and that is used to diagnose abnormal brain functioning." I knew right where to look, because you provoked my search for that word a generation ago, when I first (and not last) encountered it in one of your books. If it was used derisively about you, I can only infer that the reviewer's brain was set a-humming by a) his failure to follow your illaqueating (ensnaring) logic, b) his dizzied awe at your manifold talents, and/or c) his inability to distinguish lexiphanicism (the use of pretentious words) from lectio divina. I say, keep it up. We could all do with more brain vibrations.")

- Tsai, Michelle (2008-02-28). "Why Did William F. Buckley Jr. talk like that?". Slate. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

References

- Appel, Edward C. "Burlesque drama as a rhetorical genre: The hudibrastic ridicule of William F. Buckley, Jr.," Western Journal of Communication, Summer 1996, Vol. 60 Issue 3, pp 269–284

- Bridges, Linda, and John Coyne. Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement (Wiley, 2007) isbn=0471758175

- Buckley, James Lane (2006). Gleanings from an Unplanned Life: An Annotated Oral History. Wilmington: Intercollegiate Studies institute. ISBN 978-1-933859-11-8.

- Buckley, Reid (1999). Strictly Speaking. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-134610-4.

- Epstein, Joseph. "The Politics of William Buckley: Conservative Ideologue as Liberal Celebrity," Dissent, Oct 1972, Vol. 19 Issue 4, pp 602–61

- Farber, David. The Rise and Fall of Modern American Conservatism: A Short History (2010) pp 39–76

- Gottfried, Paul (1993). The Conservative Movement. ISBN 0-8057-9749-1

- John B. Judis (1990). William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives. New York: Touchstone. (full-scale biography). ISBN 0-671-69593-2

- Lamb, Brian (2001). Booknotes: Stories from American History. New York: Penguin. ISBN 1-58648-083-9.

- Lee, Michael J. "WFB: The Gladiatorial Style and the Politics of Provocation," Rhetoric and Public Affairs, Summer 2010, Vol. 13 Issue 2, pp 43–76

- Nash, George H. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (2006)

- Winchell, Mark Royden (1984). William F. Buckley, Jr. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8057-7431-9.

- Sarchett, Barry W. "Unreading the Spy Thriller: The Example of William F. Buckley Jr.," Journal of Popular Culture, Fall 1992, Vol. 26 Issue 2, pp 127–139, theoretical literary analysis

- Smith, W. Thomas, Jr. (2003). Encyclopedia of the Central Intelligence Agency. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4667-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Straus, Tamara (1997). The Literary Almanac: The Best of the Printed Word: 1900 to the Present. New York: High Tide Press. ISBN 1-56731-328-0.

- "William F. Buckley, Jr". C-Span American Writers II. Retrieved September 2, 2004.

- Miller, David (1990). Chairman Bill: A Biography of William F. Buckley, Jr.. New York

- Meehan, William F. III (1990). William F. Buckley Jr: A Bibliography. New York

- Sturgis, Sue. "William F. Buckley's peculiar South". William F. Buckley's peculiar South. The Institue for Southern Studies. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- Rendall, Steve. "William F. Buckley, Rest in Praise". Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- "Happy Birthday National Review!". Retrieved June 27, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - Marcus, Epstein. "OK, William F. Buckley Helped Create The Modern Conservative Movement—But What Did It Conserve?". The VDARE Foundation. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- "William F. Buckley, Jr". Misplaced Pages. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

Further reading

Further information: William F. Buckley, Jr. bibliography Further information: List of Blackford Oakes novelsExternal links

- William F. Buckley at IMDb

- Buckley Online, a complete guide to the writings William F. Buckley at Hillsdale College

- Sam Vaughan (Summer 1996). "William F. Buckley Jr., The Art of Fiction No. 146". Paris Review.

- Gordon, David (2010-05-12) The Making of a Warmonger, LewRockwell.com

- Video of Buckley debating James Baldwin, October 26, 1965, Cambridge University; digitized by UC Berkeley

- "The Collected Controversies of William F. Buckley", February 28, 2008

- "A Conversation with William F. Buckley, Jr.," Charlie Rose Show, Dec. 28, 2007 (23 min.)

- "Where does one Start? A Guide to Reading WFB," National Review Online, February 29, 2008

- "Walking the Road that Buckley Built," by Michael Johns, March 7, 2008

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New political party | Conservative Party nominee for Mayor of New York City 1965 |

Succeeded byJohn Marchi |

| Andrews McMeel Universal | |

|---|---|

| Comic strips (current) |

|

| Comic strips (historical) |

|

| Editorial cartoons | |

| Lifestyle | |

| Other | |

| The Blackford Oakes series by William F. Buckley Jr. | |

|---|---|

| Novels |

|

| Other literary works |

|

| Other articles | |

- 1925 births

- 2008 deaths

- American activists

- American anti-communists

- American columnists

- American libertarians

- American military personnel of World War II

- American novelists

- American people of Swiss-German descent

- American political pundits

- American political writers

- American Roman Catholic religious writers

- American sailors

- American spies

- American Traditionalist Catholics

- American writers of Irish descent

- Buckley family

- Connecticut Republicans

- Conservatism in the United States

- Conservative Party of New York State politicians

- Critics of Objectivism

- Deaths from diabetes

- Deaths from emphysema

- Disease-related deaths in Connecticut

- Drug policy reform activists

- Georgists

- Knights of Malta

- National Review people

- New York City politicians

- New York Republicans

- People from Manhattan

- People from Stamford, Connecticut

- People of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Traditionalist Catholic writers

- United States Army officers

- William F. Buckley, Jr.

- Writers from Connecticut

- Writers from New York City

- Yale University alumni