This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dr. Dan (talk | contribs) at 14:27, 14 October 2009 (As before, the article is about the agreement, not the Vilnius Region, nor the Suwałki Region.; the foreign language toponyms are in those seperate articles.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:27, 14 October 2009 by Dr. Dan (talk | contribs) (As before, the article is about the agreement, not the Vilnius Region, nor the Suwałki Region.; the foreign language toponyms are in those seperate articles.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)the Baltic states in the 20th century |

|---|

Post World War I

|

| World War II |

Post World War II

|

Areas

|

Demarcation lines

|

| Adjacent countries |

| Borders of Poland | |

|---|---|

The Suwałki Agreement, Treaty of Suvalkai, or Suwalki Treaty (Template:Lang-pl, Template:Lang-lt) was an agreement signed in the Polish town of Suwałki between Poland and Lithuania on October 7, 1920. Both countries had re-established their independence in the aftermath of World War I and did not have well-defined borders. They waged the Polish–Lithuanian War over territorial disputes in the Suwałki and Vilnius Regions. At the end of September 1920, Polish forces defeated the Soviets at the Battle of the Niemen River, thus militarily securing the Suwałki Region and opening the possibility of an assault on the city of Vilnius. Polish Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski, had planned to take over the city since mid-September in a false flag operation known as Żeligowski's Mutiny.

Under pressure from the League of Nations, Poland agreed to negotiate hoping to buy time and divert attention from the planned Żeligowski's Mutiny. The Lithuanians sought to achieve as much protection to Vilnius as possible. The agreement resulted in a ceasefire and established a demarcation line running through the disputed Suwałki Region up to the Bastuny railway station. The line was incomplete and did not provide adequate protection to Vilnius. Neither Vilnius or the surrounding region was explicitly addressed in the agreement, however numerous historians have described the agreement as allotting Vilnius to Lithuania.

Just a few hours after the signing of the agreement, Poland broke the treaty. Polish general Lucjan Żeligowski, acting under secret orders from Piłsudski, pretended to disobey stand-down orders from the Polish military command and marched on Vilnius. The city was taken on October 9. The Suwałki Agreement was to take effect at noon on October 10. Żeligowski established the Republic of Central Lithuania which, despite intense protests by Lithuania, was incorporated into the Second Polish Republic in 1923. The Vilnius Region remained in Poland until 1939.

Background

Main article: Polish–Lithuanian WarIn the aftermath of World War I both Poland and Lithuania gained independence, but borders in the region were not established. The most contentious issue was Vilnius (Wilno), historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with a population, according to the 1916 German census, divided about evenly between Jews and Poles, but with only a 2–3% Lithuanian minority. The Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty, signed in July 1920 between Lithuania and the Russian SFSR, drew the eastern border of Lithuania. Russia recognized large territories, including the Vilnius and Suwałki Regions, as belonging to Lithuania. In July 1920, during the Polish–Soviet War, the Red Army pushed Polish forces from the contested territories. The Lithuanian Army then moved to secure the territory as it was established by the Peace Treaty. After the Soviets were defeated in the Battle of Warsaw in mid-August, the Polish Army pushed back and came in contact with the Lithuanians in the contested Suwałki Region. The Lithuanians claimed to be defending their borders, while Poland did not recognize the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty and claimed that the Lithuanians had no rights to these territories. Poland also accused the Lithuanians of collaborating with the Soviets and thus violating the declared neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War. In the ensuing hostilities, the Polish towns of Suwałki, Sejny, and Augustów changed hands frequently. The diplomatic struggle, both directly between the two states and in the League of Nations, intensified.

Negotiations

Pressure from the League of Nations

On September 5, 1920, Polish Foreign Minister Eustachy Sapieha delivered a diplomatic note to the League of Nations asking it to intervene in the Polish–Lithuanian War. He claimed that Lithuania allowed free passage through its territory for Soviet troops and therefore violated its declared neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War. The next day Lithuania responded with a direct note to Poland in which Lithuanian Foreign Minister Juozas Purickis proposed to negotiate a demarcation line and other issues in Marijampolė. On September 8, during a planning meeting for what later was the Battle of the Niemen River, the Poles decided to maneuver through the Lithuanian territory to the rear of the Soviet Army. In an attempt to conceal the planned attack, Polish diplomats accepted the proposal to negotiate. The negotiations started on September 16 in Kalvarija, but collapsed just two days later.

The League of Nations began its session on September 16, 1920. After reports by Lithuanian representative Augustinas Voldemaras and Polish envoy Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the League adopted a resolution on September 20. It urged both states to cease hostilities and adhere to the Curzon Line. Poland was asked to respect Lithuanian neutrality if Soviet Russia agreed to do the same. A special Control Commission was to be dispatched into the conflict zone to oversee implementation of the resolution. The Lithuanian government accepted the resolution. Sapieha replied that Poland could not honor the Lithuanian neutrality or the demarcation line as Lithuania was actively collaborating with the Soviets. The Poles reserved the right of full freedom of action. The Lithuanian representative in London, Count Alfredas Tiškevičius, informed the secretariat of the League of Nations that Sapieha's telegram should be regarded as a declaration of war; he also asked that the League of Nations take immediate intervention in order to stop new Polish aggressive acts.

On September 22, 1920, Poland attacked Lithuanian units in the Suwałki Region as part of the Battle of the Niemen River. 1,700 Lithuanian troops surrendered and were taken prisoner by the Polish army. Polish forces then marched, on September 8, across the Neman River near Druskininkai and Merkinė to the rear of the Soviet forces near Grodno and Lida. The Red Army retreated. This attack, just two days after the League's resolution, damaged both Poland's and the League's reputation. Some politicians began to view Poland as an aggressor while the newly-formed League realized its own shortcomings in light of such defiance. On September 26, urged by the League, Sapieha proposed new negotiations in Suwałki. Lithuania accepted the proposal on the following day.

Negotiations in Suwałki

At the time of the negotiations, the military situation on the ground was threatening Lithuania not only in the Suwałki Region, but also in Vilnius. The Polish leader, Józef Piłsudski, feared that the Entente and the League might accept the fait accompli that had been created by the Soviet transfer of Vilnius to Lithuania on August 26, 1920. Already on September 22, Sapieha asked Paderewski to gauge the possible reaction of the League in case military units in the Kresy decided to attack Vilnius, following the example of the Italian Gabriele D'Annunzio, who in 1919 staged a mutiny and took over the city of Fiume. By agreeing to the negotiations, the Poles sought to buy time and distract attention from the Vilnius Region. The Lithuanians hoped to avoid new Polish attacks and, with help of the League, to settle the disputes.

The conference began in the evening of September 29, 1920. The Polish delegation was led by colonel Mieczysław Mackiewicz (who originated from Lithuania), and the Lithuanian delegation by general Maksimas Katche. Lithuania proposed an immediate armistice, but the Polish delegation refused. Only after the Lithuanian delegation threatened to leave the negotiation table did Poland agree to stop fighting, but only to the east of the Neman River (the Suwałki Region). Fighting to the west of the river continued. The Polish delegates demanded that the Lithuanians allow the Polish forces to use a portion of the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway and the train station in Varėna (Orany). The Lithuanians refused: their major forces were concentrated in the Suwałki Region and moving them to protect Vilnius without the railway would be extremely difficult. The Lithuanian side was ready to give up the Suwałki Region in exchange for Poland's recognition of the Lithuanian claims to Vilnius.

The Lithuanian delegation, after consultations in Kaunas on October 2, proposed their demarcation line on October 3. The line would be withdrawn about 50–80 km (31–50 mi) from the border determined by the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. On October 4, the Polish delegation, after consultations with Piłsudski, presented a counter-offer. In essence, the Lithuanians wanted a longer demarcation line to provide better protection for Vilnius and the Poles pushed for a shorter line. While Vilnius was not a topic of debate, it was on everybody's mind. On the same day the Control Commission, sent by the League according to its resolution of September 20, arrived in Suwałki to mediate the talks. The commission, led by French colonel Pierre Chardigny, included representatives from Italy, Great Britain, Spain, and Japan.

On October 5, 1920, the Control Commission presented a concrete proposal to draw the demarcation line up to the village of Utieka on the Neman River, about 10 km (6.2 mi) south of Merkinė (Merecz), and to establish a 12 km (7.5 mi) wide neutral zone along the line. On October 6, negotiations continued regarding an extension of the demarcation line. The Poles refused to move it past the village of Bastuny, claiming that the Polish army needed freedom to maneuver against the Soviet troops, even though a provisional ceasefire agreement had been reached with Soviet Russia on October 5. The Poles proposed to discuss further demarcation lines in Riga, where Poland and Russia negotiated the Peace of Riga. On the same day fighting west of the Neman River ceased as Polish troops captured the Varėna train station. On October 7, at midnight, the final Suwałki Agreement was signed. On October 8, the Control Commission stated that they could not see why the demarcation line could not be extended further than Bastuny and urged another round of negotiations.

Provisions of the agreement

The agreement was finally signed on October 7, 1920; the ceasefire was to begin at noon on October 10.. Notably, the treaty made not a single reference to Vilnius or the Vilnius Region. The agreement contained the following articles:

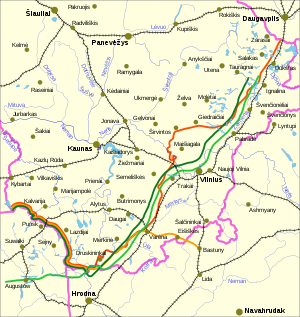

- Article I: on the demarcation line; besides setting it out, it also stated that the line "in no way prejudices the territorial claims of the two Contracting Parties." The demarcation line would start in the west following the Curzon Line until it reached the Neman River. It would follow the Neman and Merkys Rivers, leaving the town of Varėna to the Lithuanians, but its train station on the Polish side. From Varėna the line would follow Barteliai–Kinčai–Naujadvaris–Eišiškės–Bastuny (Bastūnai, Бастынь). The train station in Bastuny also remained in Polish hands. The demarcation line east of Bastuny was to be determined by a separate agreement.

- Article II: on the ceasefire; notably the ceasefire was to take place only along the demarcation line, not on the entire Polish–Lithuanian frontline (i.e. not east of Bastuny).

- Article III: on the train station in Varėna (Orany); it was to remain under Polish control but the Polish side promised unrestricted passage of civilian trains, but only two military trains per day

- Article IV: on prisoner exchange.

- Article V: on the date and time the ceasefire would start (October 10 at noon) and expire (when all territorial disputes are resolved) and which map was to be used.

Aftermath

Main article: Żeligowski's MutinyThe demarcation line drawn through the Suwałki Region for the most part remains the border between Poland and Lithuania in modern times; notably the towns of Sejny, Suwałki and Augustów remained on the Polish side. Even in the 21st century, the Suwałki Region (the present-day Podlaskie Voivodeship) remains home to the Lithuanian minority in Poland.

The most controversial issue– the future of the city of Vilnius– was not addressed. When the agreement was signed, Vilnius was garrisoned by Lithuanian troops and behind the Lithuanian lines. Yet this changed almost immediately when the staged Żeligowski's Mutiny began on October 8. Soon after the so called Żeligowski's mutiny Léon Bourgeois, President of the Council of the League of Nations, attacked Poland asserting that the occupation of Lithuania's capital Vilnius was a violation of the engagements entered into with the Council of the League of Nations, and he demanded the immediate Polish evacuation of the city.

In Piłsudski's view, signing even such a limited agreement was not in Poland's best interests, and he disapproved of it. In a 1923 speech acknowledging that he had directed Żeligowski's coup, Piłsudski stated: "I tore up the Suwałki Treaty, and afterwards I issued a false communique by the General Staff." Żeligowski and his mutineers captured Wilno, established the Republic of Central Lithuania, and after a disputed election in 1922, incorporated the republic into Poland. The conflict over Wilno dragged on until World War II. In the 21st century, the Vilnius Region (Wileńszczyzna) is the major center of the Polish minority in Lithuania.

Evaluations and historiography

Initially the Poles denied knowledge of the mutiny. They noted that the demarcation line and the ceasefire did not extend east of Bastuny. During the negotiations, the Polish delegation specifically refused to extend the line east of Bastuny, which would cut off Polish access to Vilnius, in order to allow Żeligowski's forces space for action. They saw the Suwałki Agreement strictly as a military ceasefire of minor importance. However, the presence of political representatives on both sides showed that the agreement was more than just a military demarcation. Polish diplomats also claimed that a ceasefire agreement reached on November 29 between Lithuania and Żeligowski superseded the Suwałki Agreement. The Lithuanians – particularly after losing Vilnius to Żeligowski's forces and being unable to regain control over it with their own military – considered the agreement to be a formal political treaty and used it as the basis for protests in international venues. Hence interwar Lithuanian diplomacy portrayed the agreement as a treaty that explicitly left the Vilnius Region under Lithuanian control. The Lithuanian side argued that Żeligowski's actions violated the agreement and demanded that Poland fulfill its provisions. However, since the agreement was not ratified by either side, it was not a regular bilateral treaty.

While many historians in their cursory summaries of the agreement have interpreted it as assigning Vilnius to Lithuania, and Poland's subsequent annexation of the city as a violation of the agreement, historians such as Piotr Lossowski disputes this interpretation.

References

- Vitas, Robert A. (1984-02-03). "The Polish–Lithuanian Crisis of 1938". Lituanus. 2 (30). ISSN 0024-5089.

- ^ Slocombe, George (1970). A Mirror to Geneva: Its Growth, Grandeur, and Decay. Ayer Publishing. p. 263. ISBN 0836918525.

- ^ Eidintas, Alfonsas (1999). Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Template:Pl icon Michał Eustachy Brensztejn (1919). Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od. 1 listopada 1915 r. Warsaw: Biblioteka Delegacji Rad Polskich Litwy i Białej Rusi.

- ^ Template:Lt icon Gintaras, Vilkelis (2006). Lietuvos ir Lenkijos santykiai Tautų Sąjungoje. Versus aureus. pp. 64–72. ISBN 9955-601-92-2.

- ^ Template:Lt icon Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF). Vilnius: Vilnius University, Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. 319–321. ISBN 9955-423-23-4.

- ^ Template:Lt icon Ališauskas, Kazys (1953–1966). "Lietuvos kariuomenė (1918–1944)". Lietuvių enciklopedija. Vol. XV. Boston, Massachusetts: Lietuvių enciklopedijos leidykla. p. 102. LCC 55020366.

- ^ Template:Lt icon Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF). Vilnius: Vilnius University, Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. 344–347. ISBN 9955-423-23-4.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Łossowski, Piotr (1995). Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918–1920. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. pp. 166–175. ISBN 8305127699.

- ^ Senn, Alfred Erich (1966). The Great Powers: Lithuania and the Vilna Question, 1920–1928. Studies in East European history. Brill Archive. pp. 45–46. LCC 67086623.

- "Lithuania and Poland. Agreement with regard to the establishment of a provisional "Modus Vivendi", signed at Suwalki, October 7, 1920" (PDF). United Nations Treaty Collection. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- Template:Lt icon Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF). Vilnius: Vilnius University, Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. 470–471. ISBN 9955-423-23-4.

- Kitowski, Jerzy (2006). Regional Transborder Co-operation in Countries of Central and Eastern Europe: A Balance of Achievements. Geopolitical Studies. Vol. 14. Polska Akademia Nauk. p. 492. OCLC 127107582.

- Nichol, James P. (1995). Diplomacy in the Former Soviet Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 123. ISBN 0275951928.

- Ther, Philipp (2001). Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 137. ISBN 0742510948.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Historian. 23 (2): p.244-245. 1961.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Snyder, Timothy (2004). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 030010586X.

- Miniotaitė, Gražina (2003). "The Baltic States: In Search of Security and Identity". In Krupnick, Charles (ed.). Almost NATO: Partners and Players in Central and Eastern European Security. The New International Relations of Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 282. ISBN 0742524590.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1999). Edvardas Tuskenis (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918–1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Vilnius dispute". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

The League of Nations arranged a partial armistice (Oct. 7, 1920) that put Vilnius under Lithuanian control and called for negotiations to settle all the border disputes.

- Rawi Abdelal (2001). National Purpose in the World Economy: Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective. Cornell University Press.

At the same time, Poland acceded to Lithuanian authority over Vilnius in the 1920 Suwalki Agreement.

- Glanville Price (1998). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Blackwell Publishing.

In 1920, Poland annexed a third of Lithuania's territory (including the capital, Vilnius) in breach of the Treaty of Suvalkai of 7 October 1920, and it was only in 1939 that Lithuania regained Vilnius and about a quarter of the territory occupied by Poland.

- Hirsz Abramowicz (1999). Profiles of a Lost World: Memoirs of East European Jewish Life Before World War II. Wayne State University Press.

Before long there was a change of authority: Polish legionnaires under the command of General Lucian Zeligowski 'did not agree' with the peace treaty signed with Lithuania in Suwalki, which ceded Vilna to Lithuania.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Marek Sobczyński. "PROCESY INTEGRACYJNE I DEZINTEGRACYJNE NA ZIEMIACH LITEWSKICH W TOKU DZIEJÓW" (PDF). University of Lodz. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

External links

- Text of the Treaty. United Nations Treaty Collection: Lithuania and Poland. Agreement with regard to the establishment of a provisional "Modus Vivendi", signed at Suwalki, October 7, 1920

| Polish truces and peace treaties | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Poland | |||||||||||

| Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| ||||||||||

| Second Polish Republic | |||||||||||