This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dave souza (talk | contribs) at 17:07, 16 July 2009 (defaultsort wrong book). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:07, 16 July 2009 by Dave souza (talk | contribs) (defaultsort wrong book)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) The title page of the 1877 edition The title page of the 1877 editionof Fertilisation of Orchids | |

| Author | Charles Darwin |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Natural selection Botany |

| Publisher | John Murray |

| Publication date | 15 May 1862 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| ISBN | N/A Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

Fertilisation of Orchids by Charles Darwin was published in 1862 under the full explanatory title On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing. It was his first detailed demonstration of the power of natural selection, explaining how complex ecological relationships cause coevolution between orchids and insects. Field studies and practical scientific investigation which Darwin began as a recreation, a pastime giving relief from the drudgery of writing, developed into enjoyable and challenging experiments, aided by his family, village friends and a widening circle of correspondents across Britain and worldwide. It tapped into a vogue at the time for growing exotic orchids.

The book had considerable success with botanists, and revived interest in the neglected idea that insects played a part in pollinating flowers. It opened up a new field of study directly related to Darwin's evolutionary ideas, supporting his view that natural selection led to a huge variety of forms achieving the important benefits of cross-fertilisation. The general public showed less interest, and sales of the book were disappointing, but it established Darwin as a leading botanist and was the first of a series of books on his innovative investigations into plants.

Orchids showed how the relationship between insects and plants could result in the beautiful and complex forms which natural theology attributed to a designer. By showing how practical adaptations lead to the huge variety of forms that develop from cumulative minor variations of parts of the flowers to suit new purposes, Darwin countered the prevailing view that beautiful organisms were the handiwork of the Creator. Darwin's painstaking observations, experiments and detailed dissection of the flowers explained previously unknown features, such as the puzzle of Catasetum which had been thought to have three completely different species of flowers on the same plant, and made testable predictions. His proposal that the long nectary of Angraecum sesquipedale meant that there must be a moth with an equally long proboscis was controversial at the time, but was confirmed in 1903 when Xanthopan morgani was found in Madagascar.

Background

Around 1838, during the inception of his theory of natural selection, Darwin became interested in the contribution of insect pollination to cross-fertilisation of flowers, which he thought played an important part in keeping specific forms constant. On the recommendation of Robert Brown, he read Das entdeckte Geheimnis der Natur, Christian Konrad Sprengel's work on the subject, in November 1841.

In the summer of 1841, Charles and Emma Darwin moved from the turmoil of London to the countryside, finding a quiet former parsonage in the village of Downe which became their family home, Down House. He wrote, "The flowers are here very beautiful... Larks abound here, and their songs sound most agreeably on all sides; nightingales are common." A favourite family walk took them to a beautiful spot above the quiet Cudham valley, teeming with orchids including Cephalanthera, Neottia, fly orchids and musk orchids, a spot they called "Orchis Bank". In the grounds and greenhouses of Down House, the gardeners attended to Darwin's experimental plants, which he dissected and measured using simple equipment. He continued to make observations and conduct experiments to determine the role insects played in fertilising plants. He recalled in 1862 that in twenty years of watching orchids he had never seen an insect visit a flower "excepting butterflies twice sucking O. pyramidalis and Gymnadenia", though he occasionally found that one or both pollinia had been removed from flowers, showing that they had been visited by insects.

For years Darwin's "species work" was his "prime hobby", the background to arranging publication of the Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle and the publishing of his own work on geology, and then an eight year study on barnacles. He began full time work on species in 1854, and after Wallace's discovery of the same idea led to early joint publication of their theories in 1858, Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species, published on 22 November 1859, as an abstract of his theory. This book makes significant mention of the insect pollination of plants, and in particular, outlines his findings on orchids. Immediately after publication, he was involved in producing revisions for new editions, and in research and writing Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication as the first part of his planned "Big Book" on evolution.

Pastime as diversion

Darwin followed with interest the first reviews of On the Origin of Species, many of which were favourable, and pressed on with Variation despite recurring illness, but by the spring he was tiring of the "confounded cocks Hens & Ducks". He turned for relief to questions of botany raised by his investigations, and worked on research on insectivorous plants, dimorphism in primulas, and the adaptive mechanisms that ensure cross-pollination in orchids. As an enthusiastic practical scientist, such investigations gave him a strong sense of personal enjoyment, and he relished pitting his wits against nature, following lucky hunches while using his theory as a way of looking at the world to creatively tackle problems not amenable to traditional approaches. He later wrote "I am like a gambler, & love a wild experiment."

Around the end of April 1860, Darwin discussed insect pollination with his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker, and mentioned the bee orchid. Darwin corresponded with Hooker's assistant Daniel Oliver, the senior curator at Kew Gardens, who shared these interests in plant functions and was willing to take on research topics, becoming a follower of Darwin's ideas. At the start of June, Darwin wrote to The Gardeners' Chronicle asking for readers' observations on how bee or fly orchids were fertilised. His letter described the mechanisms for insect fertilisation he had found in common British orchids, and reported his investigations and experiments that found that pollen masses were removed from Orchis morio and Orchis mascula plants in the open, but left in their pouches in adjacent plants under a glass bell jar. He wrote telling American botanist Asa Gray that he had been "so struck with admiration at the contrivances, that I have sent notice to Gardeners Chronicle", and made similar enquiries of other experts.

Darwin became engrossed in meticulous microscopic examination, tracing the complicated mechanisms of flowers that caused insects getting nectar to become transporters of pollen to cross-pollinate other plants, and on 19 July he told Hooker, "I am intensely interested on subject, just as at a game of chess." In September, he "dissected with the greatest interest" and wrote, "The contrivances for insect fertilisation in Orchids are multiform & truly wonderful & beautiful." He also studied sundews and by October had "a large mass of notes with many new facts", but set them aside "convinced that I ought to work on Variation & not amuse myself with interludes".

Research and draft

In the course of 1861, botany became a major preoccupation for Darwin, with his projects becoming serious scientific pursuits. He continued his study of orchids doggedly through the summer, writing to any possible supplier of specimens that he had yet to examine. Field naturalists, botanists and country gentry sent specimens from across the British Isles. He collected his own specimens, with his family and neighbours also contributing to the research. His aim was to show how the complex structures and life cycles of the plants could be explained by natural selection rather than being regarded as the handiwork of God, and he saw the huge variety of flowers as a collection of ad hoc evolutionary adaptations. In June, he described his examination of bee orchids as a passion, and his work on insect fertilisation of orchids as "beautiful facts".

There were several replies to Darwin's enquiry in The Gardeners' Chronicle seeking evidence to support his idea that pollen masses attached themselves to the right place on an insect's back or head, usually its proboscis, to transport the pollen to another flower. One envelope appeared to be empty when it arrived at Down House, but when he looked further before discarding it he found several insect mouthparts with pollen masses attached. To help their daughter Henrietta convalesce from illness, the Darwins arranged to spend two months in Torquay. Darwin wrote:

I have, owing to many interruptions, not been going on much with my regular work (though I have done the very heavy jobs of variation of Pigeons, Fowls, Ducks, Rabbits Dogs &c) but have been amusing myself with miscellaneous work.— I have been very lucky & have now examined almost every British Orchid fresh, & when at sea-side shall draw up rather long paper on the means of their fertilisation for Linn. Socy & I cannot fancy anything more perfect than the many curious contrivances.

He sought advice on obtaining the exotic South American Catasetum to see it eject pollen-masses, "For I am got intensely interested on subject & think I understand pretty well all the British species." They went to Torquay on 1 July, and he began writing his Orchid paper. By 10 August, he feared his paper would run "to 100 M.S. folio pages!!! The beauty of the adaptations of parts seems to me unparalleled..... I marvel often as I think over the diversity & perfection of the contrivances."

They returned from Torquay on 27 August, and he again wrote to the Gardeners' Chronicle appealing for assistance as he was "very anxious to examine a few exotic forms." His requests to the wealthy enthusiasts who had taken up the fashionable pursuit of growing rare orchids brought large numbers of specimens. These would be a test of his theory: T. H. Huxley had once asked, "Who has ever dreamed of finding an utilitarian purpose in the forms and colours of flowers?" The completed Orchis paper came to 140 folio pages, and Darwin decided against presenting it at the Linnean Society of London, thinking of publishing a pamphlet instead. He offered the draft to John Murray who agreed to publish it as a book. While Darwin feared a lack of public interest, he hoped it would serve to "illustrate how Natural History may be worked under the belief of the modification of Species." In discussions with Asa Gray about natural theology, he wrote that "it really seems to me incredibly monstrous to look at an orchid as created as we now see it. Every part reveals modification on modification."

Darwin began to include women who were botany enthusiasts in his correspondence. As a popular and acceptable activity, botany had been taken up by many middle class ladies. On the recommendation of John Lindley, Darwin wrote to Lady Dorothy Nevill who responded generously by sending numerous exotic orchids, and requested a signed photograph of him to hang up in her sitting room next to portraits of her notable friends including Hooker.

Linnean Society paper

Despite delays to the orchid book due to illness, Darwin continued to "look at it as a hobby-horse, which has given me great pleasure to ride". He was particularly astounded by the long spur of the Angraecum sesquipedale flowers, one of the orchids sent by the distinguished horticulturist James Bateman, and wrote to Hooker "Good Heavens what insect can suck it"

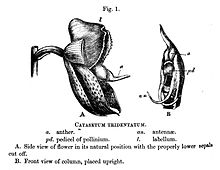

By November, a specimen of the exotic South American Catasetum orchid that Hooker had given to Darwin had shown its "truly marvellous" mechanism that shot out a pollinium at any insect touching a part of the flower "with sticky gland always foremost". This plant had astonished botanists when Robert Hermann Schomburgk stated he had seen one plant growing three distinct flowers which he believed to be three distinct genera, namely Catasetum tridentatum, Monachanthus viridis, and Myanthus barbatus. One of Darwin's correspondents told of delight at growing a beautiful specimen of Myanthus barbatus imported from Demerara, then dismay when the plant flowered the next year as a simple Catasetum.

In view of this interest, Darwin prepared a paper on Catasetum as an extract from his forthcoming book, and this was read to the Linnean Society of London on 3 April 1862. Darwin solved the puzzle by showing that the three flowers were the male, female, and hermaphrodite forms of a single species, but as they differed so much from each other, they had been classified as different genera.

Publication

On 9 February 1862, Darwin sent his manuscript off to his publisher John Murray incomplete, as he was still working on the last chapter. While anxious over whether the book would sell, he could "say with confidence that the M.S. contains many new & very curious facts & conclusions". When the book was printed, he sent out presentation copies of Orchids to all the individuals and societies who had helped him with his investigations, and to eminent botanists in Britain and abroad for review. Early responses were favourable, with Daniel Oliver writing, "It is a very extraordinary book!", and George Bentham describing it as "most valuable".

On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing was published on 15 May 1862. The reviews were favourable and a relieved Darwin, who had previously been "cursing my folly in writing it", told Hooker that "my orchis-book is a success (but I do not know whether it sells)". In August, Darwin was "well contented with the sale of 768 copies; I shd. hope & expect that the remainder will ultimately be sold."

From a publisher's viewpoint, the book sold slowly and less than 2,000 copies of the first edition were printed. An expanded edition translated into French was published in Paris in 1870, and in 1877, Murray brought out a revised and expanded second edition with the shortened title The various contrivances by which orchids are fertilised by insects. This was also published by D. Appleton & Company of New York in 1877, and German translation was published in the same year. Despite being well praised by botanists, only about 6,000 copies of the English editions had sold before 1900.

Content

In the introduction, Darwin explained his aim of meeting complaints that detailed support for his theory had been lacking in On the Origin of Species. He had chosen orchids as "amongst the most singular and most modified forms in the vegetable kingdom" in the hope of inspiring work on other species, and felt that "the study of organic beings may be as interesting to an observer who is fully convinced that the structure of each is due to secondary laws, as to one who views every trifling detail of structure as the result of the direct interposition of the Creator." He gave due credit to previous authors who had described the agency of insects in fertilising orchids, and all who had helped him.

British orchids

In the first chapter Darwin describes the British orchids he had studied, giving detailed explanations of their various mechanisms for transferring pollen to insects.

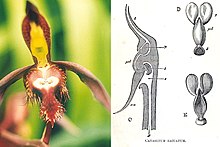

The first mechanism described is that of Orchis mascula, which serves as an introduction to the explanation of other Orchidaceae. In the upper part of the flower the male organ has two pollen masses on stalks down to adhesive balls in a cup. When an insect is attracted to land on the large projecting lower petal, the labellum, and pushes its head and proboscis into the flower, it breaks the cup and the adhesive balls attach the pollen masses to the insect. As the insect flies off, each stalk rotates the pollen mass downwards and forwards so that when the insect lands on another flower the pollen masses attached to the insect pass under the male organ and leave pollen on the female organ, achieving cross fertilisation. Darwin envisaged;

A poet might imagine, that whilst the pollinia are borne from flower to flower through the air, adhering to a moth's body, they voluntarily and eagerly place themselves, in each case, in that exact position in which alone they can hope to gain their wish and perpetuate their race."

While the bee orchid showed adaptation for self-fertilisation, its mechanism would also enable the occasional cross-fertilisation that Darwin felt was needed for vigorous survival. At Torquay Darwin had watched bees visiting spires of Spiranthes flowers, starting at the lower flowers and working their way up to the topmost flowers that attached pollen clusters to the bees, ready for them to fly to the lower flowers on another plant which had already shed their own pollen, and fertilise them, adding "to her store of honey" while perpetuating the flowers "which will yield honey to future generations of bees".

Exotic orchids

The book moves on to the various foreign orchids Darwin had received. His experiments showed that the "astonishing length" of the nectary hanging from Angraecum sesquipedale flowers implied the need for an as yet unknown moth with an equally long proboscis.

Darwin described "the most remarkable of all Orchids", Catasetum, and showed how in these flowers, "as throughout nature, pre-existing structures and capacities are utilised for new purposes". He explained the mechanism by which it fired its sticky pollen mass at an insect that touched an "antenna" on the flower, referring to experiments imitating its action using a whalebone spring. He vividly illustrated how the flower ejected the pollinium with considerable force, up to about 3 feet (1 m), by describing the touching of its antenna "whilst holding the flower at about a yard's distance from the window, as the pollinium hit the pane of glass, and adhered to the smooth vertical surface by its adhesive disc".

Final chapter

Darwin noted that the essential nectar, secreted to attract insects, seemed in some cases to also act as an excretion: "It is in perfect accordance with the scheme of nature, as worked out by natural selection, that matter excreted to free the system from superfluous or injuring substances should be utilised for purposes of the highest importance." Homologies of the orchid flowers of orchids showed them all based on "fifteen groups of vessels, arranged three within three, in alternating order". He disparaged the idea that this was an "ideal type" fixed by the Omnipotent Creator, but attributed it instead to "descent from some monocotyledonous plant, which, like so many other plants of the same division, possessed fifteen organs, arranged alternately three within three in five whorls; and that the now wonderfully changed structure of the flower is due to a long course of slow modification,— each modification having been preserved which was useful to each plant, during the incessant changes to which the organic and the inorganic world has been exposed".

Describing the final end state of the whole flower cycle as the production of seed, he described a simple experiment where he took a ripe seed capsule and arranged the seeds in a line, then counted the seeds in one-tenth of an inch (2.5 mm). By multiplication he found that each plant produced enough seeds to plant an acre of ground (0.4 ha), and the great grandchildren of a single plant could "carpet the entire surface of the land throughout the globe" if unchecked.

His conclusion was that the "contrivances and beautiful adaptations" slowly acquired through slight variations subjected to natural selection "under the complex and ever-varying conditions of life" far transcended the most fertile imagination. The mechanisms to transport the pollen of one flower or of one plant to another flower or plant underlined the importance of cross-fertilisation: "For may we not further infer as probable, in accordance with the belief of the vast majority of the breeders of our domestic productions, that marriage between near relatives is likewise in some way injurious,—that some unknown great good is derived from the union of individuals which have been kept distinct for many generations?"

Influence

Orchids presented Darwin's first detailed exposition of the power of natural selection, and gave further support for the arguments he had put forward in On the Origin of Species. He had "found the study of orchids eminently useful in showing me how nearly all parts of the flower are coadapted for fertilisation by insects, & therefore the result of n. selection". In The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, he recalled how this work had revived interest in Christian Konrad Sprengel's neglected ideas of insect fertilisation of flowers:

For some years before 1862 I had specially attended to the fertilisation of our British orchids; and it seemed to me the best plan to prepare as complete a treatise on this group of plants as well as I could, rather than to utilise the great mass of matter which I had slowly collected with respect to other plants. My resolve proved a wise one; for since the appearance of my book, a surprising number of papers and separate works on the fertilisation of all kinds of flowers have appeared; and these are far better done than I could possibly have effected. The merits of poor old Sprengel, so long overlooked, are now fully recognised many years after his death.

Darwin told Hooker in March 1862 that he had "found the study of orchids eminently useful in showing me how nearly all parts of the flower are coadapted for fertilisation by insects, & therefore the result of n. selection,–even most trifling details of structure". In May his friends were impressed by their complimentary copies of the book. George Bentham praised its value in opening "a new field for observing the wonderful provisions of Nature... a new and unexpected track to guide us in the explanation of phenomena which had before that appeared so irreconcileable with the ordinary prevision and method shown in the organised world." Daniel Oliver thought it "very extraordinary", and even Darwin's old beetle-hunting rival Charles Babington, now professor of botany at the University of Cambridge and inclined to oppose natural selection, called it "exceedingly interesting and valuable... highly satisfactory in all respects. The results are most curious and the skill shown in discovering them equally so." Hooker told Darwin that the book showed him to be "out of sight the best Physiological observer & experimenter that Botany ever saw", and was glad to note that "Bentham & Oliver are quite struck up in a heap with your book & delighted beyond expression", two leading figures among the traditional botanists who had come over to evolution.

The book achieved success in botanical circles when Bentham, in his presidential address to the Linnean Society on 24 May, praised the book as exemplifying the biological method, and said that it had nearly overcome his opposition to the Origin. He stated that "Mr Darwin has shown how changes may take place", and described it as a "legitimate hypothesis in compliance with John Stuart Mill's scientific method. This endorsement favourably influenced Miles Joseph Berkeley, Charles Victor Naudin, Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle, Jean Louis Quatrefages and Charles Daubeny. In June, Darwin told his publisher, "The Botanists praise my Orchid-book to the skies", and to Asa Gray he said, "I am fairly astonished at the success of my book with botanists." Darwin's geologist friend Charles Lyell gave it enthusiastic praise, "next to the Origin, as the most valuable of all Darwin's works." However, the book gained little attention from the general public, and in September Darwin told his cousin Fox, "Hardly any one not a botanist, except yourself, as far as I know, has cared for it." Darwin's novel views on the fertilisation of flowers were gradually assimilated, and around 1867 a great mass of work was published in this new branch of study. However, the book baffled a general public more interested in controversy over gorillas and cavemen. There were some reviews in gardening magazines, but few natural philosphers or zoologists noticed the book, and hardly any learned appraisals appeared.

The book countered the prevailing natural theology and its teleological argument of design in nature in a way that the Saturday Review thought would escape the angry polemics aroused by On the Origin of Species. The Literary Churchman welcomed "Mr. Darwin's expression of admiration at the contrivances in orchids", only complaining that it was too indirect a way of saying "O Lord, how manifold are Thy works!" Darwin wrote of his approach as a "flank movement against the enemy." By showing that the "wonderful contrivances" of the orchid have discoverable evolutionary histories, Darwin was countering claims by natural theologians that the organisms were examples of the perfect work of the Creator, and regarded these theological views as irritating misunderstandings. His interest in orchids continued and he had a hot-house built at Down House. He told Hooker "You cannot imagine what pleasure your plants give me... Henrietta & I go & gloat over them."

There was considerable controversy about Darwin's prediction that a moth would be found in Madagascar with a long proboscis matching the nectary of Angraecum sesquipedale. George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll, argued that the relationship supported the teleological argument for design by a creator. In 1867, Alfred Russel Wallace produced a detailed explanation of how the nectary could have evolved through natural selection, and in 1903 Xanthopan morgani was found as Darwin had expected.

Commemoration

In June 2005, Kent Wildlife Trust together with the London Borough of Bromley (which now includes Downe) and London’s Natural History Museum opened Downe Bank nature reserve with an open day event involving local people and wildlife experts. The nature reserve includes the area which was known to Darwin's family as "Orchis Bank", and this has been identified by experts as the species-rich setting described in the closing paragraph of On the Origin of Species where Darwin wrote "It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us." Darwin's home together with the surroundings which have been called his landscape laboratory, including specifically "Orchis Bank", was nominated in January 2009 for designation as a World Heritage Site.

The influence of Darwin's work was commemorated in the Smithsonian Institution's 15th Annual Orchid Show, Orchids Through Darwins Eyes, 24 January to 26 April 2009.

Notes

- ^ "Darwin Online: Fertilisation of Orchids". Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - van Wyhe 2008, pp. 50–51

- ^ Darwin 1958, pp. 127–128

- Darwin & Seward 1903, pp. 31–33

- Darwin 1887, pp. 114–116, 144

- Darwin 1862, pp. 34–39, 57–60

- van Wyhe 2008, pp. 45–47

- Darwin 1859, pp. 73, 193, 203

- ^ Darwin 2006, pp. 38 verso–40 verso

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 8: 1860". Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 9: 1861". Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Browne 2002, pp. 166–167

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 4061 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 26 (Mar 1863)". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2770 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 27 April (1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2776 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 30 Apr (1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2826 — Darwin, C. R. to Gardeners' Chronicle, (4 or 5 June 1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2825 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa, 8 June (1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2829 — Darwin, C. R. to Stainton, H. T., 11 June (1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2871 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 19 (July 1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2920 — Darwin, C. R. to Gordon, George (b), 17 Sept (1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 2956 — Darwin, C. R. to Oliver, Daniel, 20 Oct (1860)". Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ Browne 2002, pp. 170–172

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3174 — Darwin, C. R. to More, A. G., 2 June 1861". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3176 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa, 5 June (1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- Browne 2002, p. 174

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3190 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 19 June (1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3216 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa, 21 July (1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3221 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., (28 July – 10 Aug 1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3252 — Darwin, C. R. to Gardeners' Chronicle, (before 14 Sept 1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 509–510

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3263 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 24 Sept (1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3264 — Darwin, C. R. to Murray, John (b), 24 Sept (1861)". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3283 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa, [after 11 Oct 1861]". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3402 — Nevill, D. F. to Darwin, C. R., (before 22 Jan 1862)". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3404 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa, 22 Jan (1862)". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3411 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 25 Jan (1862)". Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3421 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 30 Jan (1862)". Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3305 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 1 Nov [1861]". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3407 — Rogers, John (a) to Darwin, C. R., 22 Jan 1862". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- Darwin 1862a

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 10: 1862". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3442 — Darwin, C. R. to Murray, John (b), 9 (Feb 1862)". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3628 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 30 (June 1862)". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3699 — Darwin, C. R. to Murray, John (b), 24 Aug (1862)". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- Darwin 1862, pp. 1–4

- ^ Darwin 1862, pp. 9–19

- Darwin 1862, pp. 91–93

- Darwin 1862, pp. 63–72

- Darwin 1862, pp. 127–129

- ^ Darwin 1862, pp. 197–203 Cite error: The named reference "orchids211" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Darwin 1862, pp. 278–279

- Darwin 1862, pp. 305–307

- Darwin 1862, pp. 343–346

- Darwin 1862, pp. 346–360

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3472 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 14 Mar (1862)". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3554 — Bentham, George to Darwin, C. R., 15 May 1862". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Browne 2002, pp. 193–194

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3566 — Babington, C. C. to Darwin, C. R., 22 May 1862". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3624 — Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., 28 June 1862". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3527 — Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., (17 May 1862)". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Kritsky 1991

- ^ Darwin 1887, pp. 270–276

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 3662 — Darwin, C. R. to Gray, Asa, 23(–4) July (1862)". Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Desmond & Moore, p. 513 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDesmondMoore (help)

- "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 4009 — Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 24(–5) Feb (1863)". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "London Borough of Bromley | A day at Darwin's entangled bank". Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- "Downe Bank - Kent Wildlife Trust". Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- "Darwin 200: Celebrating Charles Darwin's bicentenary - Darwin at Downe, Kent". Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- Darwin 1859, p. 489

- "Darwin's home nominated as world heritage site | Science". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Orchids Through Darwin's Eyes". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

References

- Browne, E. Janet (2002), Charles Darwin: vol. 2 The Power of Place, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0-7126-6837-3

- Darwin, Charles (1859), [[On the Origin of Species]] by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.), London: John Murray, retrieved 2009-02-07

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Darwin, Charles (1862a), "On the three remarkable sexual forms of Catasetum tridentatum, an orchid in the possession of the Linnean Society", Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, no. Botany 6 (published 3 April 1862), pp. 151–157, retrieved 2009-02-07

- Darwin, Charles (1862), On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing, London: John Murray, retrieved 2009-02-07

- Darwin, Charles (1887), Darwin, Francis (ed.), The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter, London: John Murray, retrieved 2009-02-07

- Darwin, Francis; Seward, A. C. (1903), More Letters of Charles Darwin. A record of his work in a series of hitherto unpublished letters, London: John Murray, retrieved 2009-02-07

- Darwin, Charles (1958), Barlow, Nora (ed.), [[The Autobiography of Charles Darwin]] 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his granddaughter Nora Barlow, London: Collins, retrieved 2009-02-07

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Darwin, Charles (2006), "Journal", in van Wyhe, John (ed.), [Darwin's personal 'Journal' (1809-1881)], Darwin Online, CUL-DAR158.1-76, retrieved 2009-02-07

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991), Darwin, London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group, ISBN 0-7181-3430-3

- Kritsky, Gene (1991), "Darwin's Madagascan Hawk Moth prediction" (pdf), American Entomologist, vol. 37, pp. 206–9, retrieved 2009-02-09

- van Wyhe, John (2008), Darwin: The Story of the Man and His Theories of Evolution, London: Andre Deutsch Ltd (published 1 September 2008), ISBN 0-233-00251-0