This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Ghanadar galpa (talk | contribs) at 11:41, 8 January 2008 (Undid revision 182931992 by 86.162.66.246 (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:41, 8 January 2008 by Ghanadar galpa (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 182931992 by 86.162.66.246 (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

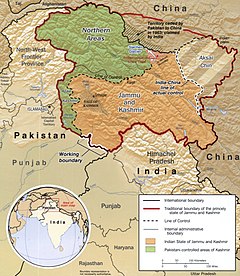

The Kashmir conflict refers to the territorial dispute between India and Pakistan (and between India and the People's Republic of China) over Kashmir, the northwesternmost region of the Indian subcontinent.

India claims the entire erstwhile Dogra princely state of Jammu and Kashmir and presently administers approximately half the region including most of Jammu, Kashmir Valley, Ladakh and the Siachen Glacier. India's claim is contested by Pakistan which controls a third of Kashmir, mainly Muzaffarabad and the northern areas of Gilgit and Baltistan. The Kashmiri region under Chinese control is known as Aksai Chin. In addition, China also controls the Trans-Karakoram Tract, also known as the Shaksam Valley, that was ceded to it by Pakistan in 1963.

India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir: in 1947, 1965, and 1999. India and China have clashed once, in 1962 over Aksai Chin as well as the northeastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. India and Pakistan have also been involved in several skirmishes over Siachen Glacier. Since the 1990s, the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir has been hit by confrontation between Pakistan-supported Islamist terrorists and the Indian army, which has resulted in thousands of deaths.

Partition, dispute and war

In 1935, British rulers compelled the Dogra King of Jammu and Kashmir to lease parts of his kingdom, which were to make up the new Province of the North-West Frontier, for 60 years. This move was designed to strengthen the northern boundaries, especially from Russia.

In 1947, the British dominion of India came to an end with the creation of two new nations, India and Pakistan. Each of the 562 Indian princely states joined one of the two new nations: secular India or Muslim Pakistan. Jammu and Kashmir had a predominantly Muslim population but a Hindu ruler, and was the largest of these autonomous states and bordered both modern countries. Its ruler was the Dogra King (or Maharaja) Hari Singh. Hari Singh preferred to remain independent and sought to avoid the stress placed on him by either India and Pakistan by playing each against the other.

However, in October 1947, Pakistani tribals (kabailis) from North Waziristan, aided and supported by Pakistani soldiers, invaded Kashmir. India contends that the tribal invasion was an attempt to force the Maharajah out of power as he had avoided deciding Kashmir's fate during partition. The Maharajah was not able to withstand the invasion; he ceded Kashmir to India. The Instrument of Accession was accepted by Lord Mountbatten, Governor General of India October 27, 1947.

The Pakistani theory contests this narrative. Pakistan contends that the tribal invasion forced the Maharajah to accede to India under duress and after the Maharaja had already fled Kashmir. Mohammad Ali Jinnah ordered the Pakistani Army to stop the accession of Kashmir to India by sending regular troops to the area in support of tribals who had already invaded Kashmir on behalf of Pakistani Muslims in Punch District. However, General Sir Frank Messervy, the first and then Army chief of Pakistan refused Jinnah's order on the grounds that it would have constituted an attack against his own British counterparts in the Indian Army. Pakistan never withdrew its troops from the portion of Kashmir under its control, thus making it impossible for India to hold a plebiscite.

Timeline

The following is a timeline of the Kashmir conflict.

- August 15, 1947: Independence and partition of British India into India and Pakistan.

- October 1947: Pashtuns from Pakistan's Afghania storm Kashmir, Maharaja of Kashmir asks India for help.

- 1947/1948: Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

- 1965: Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

- December 6, 1971: Indo-Pakistani War of 1971; Secession of East Bangla

- 1972: Republic of India and Pakistan agree to respect the cease-fire as Line of Control.

- April 13, 1984: The Indian Army takes Siachen Glacier region of Kashmir

- 1989: Militancy begins in Kashmir

- February 5, 1990: Solidarity day is observed throughout Pakistan and Azad Kashmir for the alleged massacres by Indian armed forces

- 1999: Kargil War

- July 14-16, 2001: General Pervez Musharraf and Atal Behari Vajpayee meet for peace talks.

- October 2001: Kashmiri assembly in Srinagar attacked (38 people dead).

- December 2001: Attack on Indian parliament in New Delhi.

- May 2, 2003: India and Pakistan restore diplomatic ties.

- July 11, 2003: Delhi-Lahore bus service resumes

- September 24, 2004: Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and President Musharraf meet in New York during UN General Assembly.

- July, 2006 : Second round of Indo-Pakistani peace talks.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

Main article: Indo-Pakistani War of 1947The irregular Pakistani tribals made rapid advances into Kashmir (Baramulla sector) after the rumours that the Maharaja was going to decide for the union with India. Maharaja Hari Singh of Kashmir asked the Government of India to intervene. However, the Government of India pointed out that India and Pakistan had signed an agreement of non-intervention (maintenance of the status quo) in Jammu and Kashmir; and although tribal fighters from Pakistan had entered Jammu and Kashmir, there was, until then, no iron-clad legal evidence to unequivocally prove that the Government of Pakistan was officially involved. It would have been illegal for India to unilaterally intervene (in an open, official capacity) unless Jammu and Kashmir officially joined the Union of India, at which point it would be possible to send in its forces and occupy the remaining parts.

The Maharaja desperately needed the Indian military's help when the Pakistani tribal invaders reached the outskirts of Srinagar. Before their arrival into Srinagar, India argues that Maharaja Hari Singh completed negotiations for acceding Jammu and Kashmir to India in exchange for receiving military aid. The agreement which ceded Jammu and Kashmir to India was signed by the Maharaja and Lord Mountbatten.

Pakistan contends that the Maharaja signed the document after having fled Kashmir, and thus forfeit his right to decide Kashmir's future. Outside observers such as Alistair Lamb have noted that it is likely that Indian troops were in Kashmir before any treaty was ever signed. Pakistan also claims that the Maharaja acted under duress, and that the accession of Kashmir to India is invalidated by the Standstill Agreement between India and Pakistan, which was designed to maintain the "status quo". India counters that the invasion of Kashmir by tribals, allegedly aided and instigated by the Pakistani government, had rendered the agreement null and void. India argues that the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India was the decision of the ruler Hari Singh, but also reflected the will of the people living in Jammu and Kashmir, though Pakistan argues that it was against the will of Kashmiri people.

The resulting war over Kashmir, the First Kashmir War, lasted until 1948, when India moved the issue to the UN Security Council. The UN previously had passed resolutions setting up for the monitoring of the conflict in Kashmir. The committee it set up was called the United Nations Committee for India and Pakistan. Following the set up of the UNCIP the UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on April 21, 1948. The resolution imposed that an immediate cease-fire take place and said that Pakistan should withdraw all presence and had no say in Jammu and Kashmir politics. It stated that India should retain a minimum military presence and stated "that the final disposition of the State of Jammu and Kashmir will be made in accordance with the will of the people expressed through the democratic method of a free and impartial plebiscite conducted under the auspices of the United Nations". The cease fire took place December 31, 1948.

At that time, the Indian and Pakistani governments agreed to hold the plebiscite but neither side actually removed its troops. The plebiscite never took place, leading the UN Security Council to pass several more resolutions which reaffirmed its earlier resolution.

Aftermath of war

The Treaty of Accession signed by Maharaja Hari Singh, was ratified by the parliament of the kingdom, and by a political party of Kashmir, the National Conference led by Sheikh Abdullah. It should be noted however, that the Kashmiri parliament was largely made up of personal appointments made by the Maharaja. Under the leadership of Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, a Constituent Assembly of Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (which was also its Legislative Assembly) had ratified the State's accession to India and had adopted a constitution calling for a perpetual merger of the state with India. This constitution was promulgated 26 January 1957, making Jammu and Kashmir as the only state of India to have a separate constitution, much to the displeasure of many nationalists in India.

Pakistan still asks for a plebiscite in Kashmir under the UN. However, India is no longer willing to allow a plebiscite as it claims that the situation has changed and that a large number of the Hindus who once lived in Kashmir were forced to move out due to threat from separatist activities. It also claims that Pakistan or China are not willing to demilitarize areas occupied by them.

Kashmiri nationalists argue that merger in India was conditional upon a large degree of autonomy that was to be awarded to the state. Under the Treaty of Accession, Kashmir was to defer only matters of foreign affairs and defence to India. The National Conference has, since the termination of this treaty, called upon India for greater autonomy. The largest pro-Indian political figures in Kashmir all argue for the widespread autonomy guaranteed to Kashmiris by Nehru.

The ceasefire line is known as the Line of Control (dotted line) and is the pseudo-border between India and Pakistan in most of the Kashmir region.

Sino-Indian War

Main article: Sino-Indian WarIn 1962, troops from the People's Republic of China and India clashed in territory claimed by both. China won a swift victory in the war, resulting in the Chinese administration of the region called Aksai Chin, which continues to date, as well as a strip along the eastern border. In addition to these lands, another smaller area, the Trans-Karakoram, was demarcated as the line of control between China and Pakistan, although parts on the Chinese side are claimed by India to be parts of Kashmir. The line that separates India from China in this region is known as the Line of Actual Control.

1965 and 1971 wars

Main article: Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 Main article: Indo-Pakistani War of 1971In 1965 and 1971, heavy fighting again broke out between India and Pakistan. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 resulted in the defeat of Pakistan and Pakistan Military's surrender in East Pakistan (Bangladesh). The Simla Agreement was signed in 1972 between India and Pakistan. By this treaty, both countries agreed to settle all issues by peaceful means and mutual discussions in the framework of the UN Charter.

Rise of militancy

Main article: Terrorism in KashmirIn 1989, a widespread armed insurgency started in Kashmir, which continues to this day. India contends that this was largely started by the large number of Afghanistani mujahideen who entered the Kashmir valley following the end of the Soviet-Afghan War, though Pakistan and Kashmiri nationalists argue that Afghan mujahideen did not leave Afghanistan in large numbers until 1992, three years after the insurgency began. Yasin Malik, a leader of one faction of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front,along with Ashfaq Majid Wani and Bitta Karate, was one of the Kashmiris to organize militancy in Kashmir. However since 1995, Malik has renounced the use of violence and calls for strictly peaceful methods to resolve the dispute.

Pakistan claims these insurgents are Jammu and Kashmir citizens, and they are rising up against the Indian Army in an independence movement. It also says the Indian Army is committing serious human rights violations to the citizens of Jammu and Kashmir. It denies that it is giving armed help to the insurgents. India claims these insurgents are Islamic terrorist groups from Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Afghanistan, fighting to make Jammu and Kashmir part of Pakistan. It believes Pakistan is giving armed help to the terrorists, and training them in Pakistan. It also says the terrorists have been killing many citizens in Kashmir, and committing human rights violations, while denying that its own armed forces are responsible for the human rights abuses that are well-documented by international observers such as Amnesty International.

The Pakistani government calls these insurgents, "Kashmiri freedom fighters", and claims that it gives only moral and diplomatic support to these insurgents, though India believes they are Pakistan-supported terrorists from Pakistan Administered Kashmir.

Cross-border troubles

The border and the Line of Control separating Indian and Pakistani Kashmir passes through some exceptionally difficult terrain. The world's highest battleground, the Siachen Glacier is a part of this difficult-to-man boundary. Even with 200,000 military personnel, India maintains that it is infeasible to place enough men to guard all sections of the border throughout the various seasons of the year. Pakistan has indirectly acquiesced its role in failing to prevent "cross border terrorism" when it agreed to curb such activities after intense pressure from the Bush administration in mid 2002.

The Government of Pakistan has repeatedly claimed that by constructing a fence along the line of control, India is violating the Shimla Accord. However, India claims the construction of the fence has helped decrease armed infiltration into Indian-administered Kashmir.

In 2002 Pakistani President and Army Chief General Pervez Musharraf promised to check infiltration into Jammu and Kashmir.

Human rights abuse

Claims of human rights abuses have been made concerning on both the Indian Armed Forces and the armed militants operating in Jammu and Kashmir. . Some Kashmiri Muslims and Pakistanis contend that Indian Armed Forces are responsible for much of the human rights abuses in Kashmir,.

Reasons behind the dispute

Ever since the Partition of India in 1947, both India and Pakistan have staked their claim to Kashmir. These claims are centred on historical incidents and on religious affiliations of the Kashmiri people. The whole Kashmir issue has caused longstanding enmity between post-Colonial India and newly created Muslim Pakistan. It arose as a direct consequence of the partition and independence of the Indian subcontinent in August 1947. The state of Jammu and Kashmir, which lies strategically in the Northwest of the subcontinent, bordering China and the former Soviet Union, was a princely state ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh. In geographical terms, the Maharaja could have joined either of the two new Dominions. Although urged by the Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, to determine the future of his state before the transfer of power took place, Hari Singh demurred. For over two months, the state of Kashmir was independent.

In October 1947 tribesmen from Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province invaded the Poonch District of Kashmir in support of a rebellion by Muslims against the Maharaja's taxation policies, and with, as India contends, the aid of Pakistani forces. The Kashmiri Dogra army was quickly overrun by these tribesmen who then looted and plundered the overrun areas. Faced with a deteriorating human rights situation, the Maharaja fled Kashmir and requested assistance from the Government of India. Lord Mountbatten, who had become India's Governor General, argued that the provision of assistance to an independent state could lead to an inter-Dominion War. He therefore advised that Hari Singh should first accede to the Union of India before any Indian forces were used to control the situation. Kashmir thus became a part of India and on 27th October 1947, Indian troops were airlifted to Srinagar. Fighting between the tribesmen and Indian forces intensified, spreading to Ladakh, Baltistan and Gilgit. The Pakistani army officially entered the war in May 1948 on the grounds that the presence of Indian troops in Kashmir constituted a great threat to Pakistan's own national security. Pakistan further contends that because the Maharaja fled Kashmir, he gave up his right to decide the fate of Kashmir, and that even if he could decide its fate, he did so under duress, which invalidates his claims. Outside observers also note that Indian troops were likely in Kashmir before the Maharaja signed the treaty, noting that road conditions and the Maharaja's own diary suggest that reaching Delhi within the timeframe indicated by India may would have been impossible.

The Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, referred the dispute to the United Nations, and a cease-fire was agreed on 1 January 1949. The UN resolution asked the invading Pakistani army to withdraw to the pre-war international border and instructed India to hold a plebiscite to determine the will of the people. The plebiscite has, however, never ever been held since to this day and Pakistani army too did not leave the portion of Kashmir occupied by them. This Pakistani held area is currently administered in two separate units, called Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas.

Kashmir remains bitterly divided on the ground; two-thirds of it (known as the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir) compromising Jammu, the Valley of Kashmir and the sparsely populated Buddhist area of Ladakh are controlled by India; one-third is administered by Pakistan. This area includes a narrow strip of land (Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas) compromising the Gilgit Agency, and Baltistan and the former kingdoms of Hunza and Nagar. Attempts to resolve the 'core issue' through political discussion were unsuccessful. In September 1965 war broke out again between Islamabad and Delhi. The United Nations called for a yet another cease-fire and peace was restored once again following the Tashkent Declaration in 1966, by which both nations returned to their original positions along the demarcated line. After the 1971 war and the creation of independent Bangladesh under the terms of the 1972 Simla Agreement, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of India and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan agreed that neither side would seek to alter the cease-fire line in Kashmir, which was renamed as the Line of Control, "unilaterally, irrespective of mutual differences and legal interpretations".

In 1989 Pakistan back terrorist organizations mounted an armed insurgency in the valley. The mass movement, which gained momentum through out 1990s, was repressed by the Indian authorities.

Numerous violations of the Line of Control including the famous incursions at Kargil which led to the Kargil war as well as sporadic clashes on the Siachen Glacier where both countries maintain forces at altitudes rising to 20,000 ft, add to concern for the stability of the hostile region.

Indian view

The Indian claim to Kashmir centers on the agreement between the Dogra Maharaja Hari Singh, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Lord Mountbatten according to which the erstwhile Kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir became an integral part of the Union of India through the Instrument of Accession. It also focuses on India's claim of secular society, an ideology that is not meant to factor religion into governance of major policy and thus considers it irrelevant in a boundary dispute. Another argument by India is that, in India, minorities are very well integrated, with some members of the minority communities holding positions of power and influence in India. Even though more than 80% of India's population practices Hinduism, a former President of India, A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, is a Muslim while Sonia Gandhi, the parliamentary leader of the ruling Congress Party, is a Roman Catholic. The current prime minister of India, Manmohan Singh, is a Sikh and leader of opposition, Lal Krishan Advani, is a Hindu.

In short, India holds that,

- For the UN Resolution mandating a plebiscite to be valid, Pakistan should first vacate its part of Kashmir.

- The Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir had unanimously ratified the Maharaja's instrument of Accession to India and had adopted a constitution for the state that called for a perpetual merger of the state with the Indian Union. India claims that this body was a representative one, and that its views were those of the Kashmiri people at the time.

- India does not accept the Two Nation Theory that forms the basis of Pakistan.

- The state of Jammu and Kashmir was made autonomous by the Article 370 of the Constitution of India, though this autonomy has since been reduced

- India alleges that most of the terrorists operating in Kashmir are themselves from Pakistan Administered Kashmir and that Pakistan has been involved in state sponsored terrorism.

- India states that despite Pakistan being named as an "Islamic Republic", Pakistan has been responsible for one of the worst genocide of Muslims when it killed millions of its own countrymen in East Pakistan in the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities. India also cites the violent repressions of Balochs and other internal sectarian violences in Pakistan.

- The Indian Government believes that Pakistan has used the Kashmir issue more as "a diversionary tactic" from internal and external issues.

- India regards Pakistan's claim to Kashmir based largely on religion alone to be no longer correct because India claims that it now has more Muslims than Pakistan, though no accurate figures are available to confirm this..

- India also points to articles and US reports which suggest that the terrorists are funded mostly by Pakistan as well as through criminal means like from the illegal sale of arms and narcotics as well as through circulating counterfeit currency in India. India argues that since many Kashmiri terrorists are also known to resort to unlawful rackets like extortion and bank robberies to fund their activities, they are nothing more than felons under the guise of "freedom fighters".

Pakistani view

Pakistan's claims to the disputed region are based on the rejection of Indian claims to Kashmir, namely the Instrument of Accession. Pakistan insists that the Maharaja was not a popular leader, and was regarded as a tyrant by most Kashmiris. Pakistan also accuses India of hypocrisy, as it refused to recognize the accession of Junagadh to Pakistan and Hyderabad's independence, on the grounds that those two states had Hindu majorities (in fact, India occupied and forcibly integrated those two territories). Furthermore, as he had fled Kashmir due to Pakistani invasion, Pakistan asserts that the Maharaja held no authority in determining Kashmir's future. Additionally, Pakistan argues that even if the Maharaja had any authority in determining the plight of Kashmir, he signed the Instrument of Accession under duress, thus invalidating the legitimacy of his actions.

Pakistan also claims that Indian forces were in Kashmir before the Instrument of Accession was signed with India, thus, Indian troops were in Kashmir in violation of the Standstill Agreement which was designed to maintain the status quo in Kashmir. This view is also echoed by many Western experts on the Kashmir conflict. .

Further, Pakistan has alleged that Indian Armed Forces, its paramilitary groups, and counter-insurgent militias have been responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Kashmiri civilians and gang-rapes of hundreds of women..

In short, Pakistan holds that

- The popular Kashmiri insurgency demonstrates that the Kashmiri people no longer wish to remain within India. Pakistan suggests that this uprising is pro-Pakistani, while Kashmiri nationalists argue that such a move is for independence.

- Brutal Indian counterinsurgency tactics merit international monitoring of the Kashmir conflict.

- According to the two-nation theory by which Pakistan was formed, Kashmir should have been with Pakistan, because it has a Muslim majority (it should be noted that India has never accepted the Two-Nation Theory, which is the basis for Pakistan's existence).

- India has shown disregard to the resolutions of the UN (by not holding a plebiscite). India however asserts that since 1947 the demographics of Pakistani side of Kashmir has been altered with generations of non-Kashmiris allowed to take residence in Pakistan Administered Kashmir. This, India believes, would heavily influence any voting in favour of Pakistan, rendering the idea of a free and fair plebiscite impossible.

- The Kashmiri people have now been forced by the circumstances to rise against the repression of the Indian army and uphold their right of self-determination through militancy. Pakistan claims to give the Kashmiri freedom-fighters moral, ethical and military support (see 1999 Kargil Conflict).

Water dispute

Another reason behind the dispute over Kashmir is water. Kashmir is the origin point for many rivers and tributaries of the Indus River basin. They include Jhelum and Chenab which primarily flow into Pakistan while other branches - the Ravi, Beas and the Sutlej irrigate northern India. Pakistan has been apprehensive that in a dire need India under whose portion of Kashmir lies the origins and passage of the said rivers, would use its strategic advantage and withhold the flow and thus choke the agrarian economy of Pakistan. The Boundary Award of 1947 meant that the headworks of the chief irrigation systems of Pakistan were left located in Indian Territory.

Furthermore, the British commission in charge of Partition handed Gurdaspur district over to India, despite being a Muslim majority district of Punjab. The British claims were that if India did not control Gurdaspur, then Pakistan could simply cut off water supplies to Amritsar. However, Gurdaspur is the district in which all roads from India in Kashmir run, and thus, Pakistan alleges that the British effectively decided the fate of Kashmir by giving India a lifeline in Kashmir. Pakistan also alleges that the British reasoning for handing over Gurdaspur was flawed and unfair because while Pakistan was denied Gurdaspur district on the grounds of Indian water security, India maintained control over Pakistani water by retaining all the districts of Punjab in which major Pakistani river had their headwaters. Essentially this is seen as a veto power held by India over Pakistan agriculture. The Indus Waters Treaty signed in 1960 resolved most of these disputes over the sharing of water, calling for mutual cooperation in this regard. This treaty faced issues raised by Pakistan over the construction of dams on the Indian side which limit water to the Pakistani side.

Map issues

As with other disputed territories, each government issues maps depicting their claims in Kashmir as part of their territory, regardless of actual control. It is illegal in India to exclude all or part of Kashmir in a map. It is also illegal in Pakistan not to include the state of Jammu and Kashmir as disputed territory, leading to many arguments and disputes. Non-participants often use the Line of Control and the Line of Actual Control as the depicted boundaries, as is done in the CIA World Factbook, and the region is often marked out in hashmarks, although the Indian government strictly opposes such practices. When Microsoft released a map in Windows 95 and MapPoint 2002, a controversy was raised because it did not show all of Kashmir as part of India as per Indian claim.

Sources from:

UN: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on the map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control of Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by the Republic of India and the Government of Pakistan since 1972. Both the parties have not yet agreed upon the final status of the region and nothing significant has been implemented since the peace process began in 2004.

Islamabad: The Government of Pakistan maintains un-provisionally and unconditionally stating that the formal "Accession of Jammu and Kashmir" to Pakistan or even to the Republic of India remains to be decided by UN plebiscite and only according to their own volition of Kashmir regional state.

New Delhi: The Government of India states that "the external artificial boundaries of Hindustan, especially concerning the Kashmir region under its jurisdiction created by a foreign super power are neither correct nor authenticated".

Recent developments

India continues to assert their sovereignty or rights over the entire region of Kashmir, while Pakistan maintains that it is a disputed territory. In international forums however India has offered to make the Line of Control a permanent border on a number of occasions, though Pakistan argues that the status quo is the problem, and cannot be considered a solution to the very problem which it has caused. Officially Pakistan insists on a UN sponsored plebiscite, so that the people of Kashmir will have a free say in which country all of Kashmir should be incorporated into. Unofficially, the Pakistani leadership has indicated that they would be willing to accept alternatives such as a demilitarized Kashmir, if sovereignty of Azad Kashmir was to be extended over the Kashmir valley, or the ‘Chenab’ formula, by which India would retain parts of Kashmir on its side of the Chenab river, and Pakistan the other side - effectively re-partioning Kashmir on communal lines. Most Kashmiri politicians from all spectrums oppose this, though some, such as Sajjad Lone, have in recent months suggested that non-Muslim part of Jammu and Kashmir be separated from Kashmir and handed to India. Some political analysts say that the Pakistan terrorist state policy shift and mellowing down of its aggressive stance may have to do with its total failure in the Kargil War and the subsequent 9/11 attacks that put pressure on Pakistan to alter its terrorist position. Further many neutral parties to the dispute have noted that UN resolution on Kashmir is no longer relevant. Even the European Union has viewed that the plebiscite is not in Kashmiris' interest. The report also notes, that the UN-laid down conditions for such a plebiscite have not been, and can no longer be, met by Pakistan. Even the Hurriyat Conference observed in 2003, that "Plebiscite no longer an option" Besides the popular factions that support either parties, there is a third faction which supports independence and withdrawal of both India and Pakistan. These have been the respective stands of the parties for long, and there have been no significant change over the years. As a result, all efforts to solve the conflict have been futile so far.

The Freedom in the World 2006 report categorized the Indian-administered Kashmir as "partly free", and Pakistan-administered Kashmir as well as the country of Pakistan "not free". India claims that contrary to popular belief, a large proportion of the Jammu and Kashmir populace wish to remain with India. In a 2002 survey by MORI in the Indian administered areas around 61% of the respondents said they felt they would be better off politically and economically as an Indian citizen, with only 6% preferring Pakistan instead.

Conflict in Kargil

Main article: Kargil War

In mid-1999 insurgents and Pakistani soldiers from Pakistani Kashmir infiltrated into Jammu and Kashmir. During the winter season, Indian forces regularly move down to lower altitudes as severe climatic conditions makes it almost impossible for them to guard the high peaks near the Line of Control. The insurgents took advantage of this and occupied vacant mountain peaks of the Kargil range overlooking the highway in Indian Kashmir, connecting Srinagar and Leh. By blocking the highway, they wanted to cut-off the only link between the Kashmir Valley and Ladakh. This resulted in a high-scale conflict between the Indian Army and the Pakistan Army.

At the same time, fears of the Kargil War turning into a nuclear war, provoked the then-US President Bill Clinton to pressure Pakistan to retreat. Faced with mounting losses of personnel and posts, Pakistan Army withdrew the remaining troops from the area ending the conflict. India reclaimed control of the peaks which they now patrol and monitor all year long.

Efforts to end the crisis

The 9/11 attacks on the US resulted in the US government wanting to restrain militancy in the world, including Pakistan. Due to Indian persuasion on US Congress Members, the US urged Islamabad to cease infiltrations, which continue to this day, by Islamist militants into Indian-administered Kashmir. In December 2001, a terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament linked to Pakistan resulted in war threats, massive deployment and international fears of nuclear war in the subcontinent.

After intensive diplomatic efforts by other countries, India and Pakistan began to withdraw troops from the international border June 10, 2002, and negotiations began again. Effective November 26, 2003, India and Pakistan have agreed to maintain a ceasefire along the undisputed International Border, the disputed Line of Control, and the Siachen glacier. This is the first such "total ceasefire" declared by both nuclear powers in nearly 15 years. In February 2004, Pakistan further increased pressure on Pakistanis fighting in Indian-administered Kashmir to adhere to the ceasefire. The nuclear-armed neighbours also launched several other mutual confidence building measures. Restarting the bus service between the Indian- and Pakistani- administered Kashmir has helped defuse the tensions between the countries. Both India and Pakistan have also decided to cooperate on economic fronts.

On Dec. 5, 2006, Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf told an Indian TV channel that Pakistan would give up its claim on Kashmir if India accepted some of his peace proposals, including a phased withdrawal of troops, self-governance for locals, no changes in the borders of Kashmir, and a joint supervision mechanism involving India, Pakistan and Kashmir, the BBC reported. Musharraf also stated that he was ready to give up the United Nation resolutions regarding Kashmir .

Recent events

The 2005 Kashmir earthquake, which killed over 80,000 people, led to India and Pakistan finalizing negotiations for the opening of a road for disaster relief through Kashmir.

See also

- List of topics on the land and the people of Jammu and Kashmir

- History of Jammu and Kashmir

- Timeline of the Kashmir conflict

- Kashmiriyat - a socio-cultural ethos of religious harmony and Kashmiri consciousness.

- Instrument of Accession (Jammu and Kashmir) to the Country / Dominion of India

- Indo-Pakistani Wars

- Trans-Karakoram Tract

- Aksai Chin

- Kargil War or the Indo-Pakistani War of 1999

- LOC Kargil, a 2003 Bollywood war film based on "Kargil War"

- Terrorism in Kashmir

- Indian Kashmir barrier

Further reading

- Drew, Federic. 1877. “The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations.&;#8221; 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu. 1971.

- Dr. Ijaz Hussain, 1998, Kashmir Dispute: An International Law Perspective, National Institute of Pakistan Studies

- Alastair Lamb, Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy 1846-1990 (Hertingfordbury, Herts: Roxford Books, 1991)

- Kashmir Study Group, 1947-1997, the Kashmir dispute at fifty : charting paths to peace (New York, 1997)

- Jaspreet Singh, Seventeen Tomatoes -- an unprecedented look inside the world of an army camp in Kashmir (Vehicule Press; Montreal, Canada, 2004)

- Navnita Behera, State, identity and violence : Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh (New Delhi: Manohar, 2000)

- Sumit Ganguly, The Crisis in Kashmir (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press; Cambridge : Cambridge U.P., 1997)

- Sumantra Bose, The challenge in Kashmir : democracy, self-determination and a just peace (New Delhi: Sage, 1997)

- Robert Johnson, 'A Region in Turmoil' (London and New York, Reaktion, 2005)

- Prem Shankar Jha, Kashmir, 1947: rival versions of history (New Delhi : Oxford University Press, 1996)

- Manoj Joshi, The Lost Rebellion (New Delhi: Penguin India, 1999)

- Alexander Evans, Why Peace Won't Come to Kashmir, Current History (Vol 100, No 645) April 2001 p170-175.

- Younghusband, Francis and Molyneux, E. 1917. Kashmir. A. & C. Black, London.

- Victoria Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict I.B. Tauris, London.

- Victoria Schofield, Kashmir in the Crossfire, I.B. Tauris, London.

- Muhammad Ayub, An Army; Its Role & Rule (A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil 1947-1999). Rosedog Books,Pittsburgh,pennsylvnia USA.2005.ISBN 0-8059-9594-3

References

| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Cohen, Stephen Philip (2004). The idea of Pakistan. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 51.

- Timeline of the conflict - BBC

- "Interview: "I have never been on Pakistan's 'favoured guests' list"". Newsline. 2005-01-01. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - FBI has images of terror camp in Pak

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1762146.stm

- India Today August 21, 2006, Pg 91

- US Embassy

- Strategic Analysis: A Monthly Journal of the IDSA Jan-Mar 2002 (Vol. XXVI No.1)

- CIA On Net

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1762146.stm

- http://www.mofa.gov.pk/Pages/Brief.htm

- http://www.mediamonitors.net/suliman1.html

- http://www.countercurrents.org/kashmir-hashmi310307.htm

- Pakistan’s Kashmir Policy after the Bush Visit to South Asia Strategic Insights Volume V, Issue 4 (April 2006) by Peter R. Lavoy

- Kickstart Kashmir - Times of India.

- EU: Plebiscite not in Kashmiris’ interest - November 30, 2006, Pak Observer

- REPORT on Kashmir: present situation and future prospects Committee on Foreign Affairs Rapporteur: Baroness Nicholson of Winterbourne

- [http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/bline/2003/07/01/stories/2003070102280400.htm Jul 01, 2003, The Hindu

- Ipsos MORI - Kashmiris Reject War In Favour Of Democratic Means

External links

- Kashmir Watch: In-depth coverage on Kashmir conflict

- Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF)

- Legal Documents related to Kashmir including treaties

- Centre for Contemporary Conflict on Kargil War

- BBC articles on Kashmir

- Kashmir Conflict

- Recent Kashmir developments

- The Political Economy of the Kashmir Conflict U.S. Institute of Peace Report, June 2004

- The Jammu and Kashmir issue

- A peep into Kashmir History

- The Kashmir dispute-cause or symptom?

- LoC-Line of Control situation in Kashmir

- Jammu & Kashmir-The Basic Facts

- Introduction of the Kashmir dispute

- An outline of the history of Kashmir

- Images of Muzaffarabad (Capital City of Pakistani controlled Kashmir)

- Images of Pakistan controlled Kashmir

- News Coverage of Kashmir

- Jammu & Kashmir on The Indian Analyst News, Analysis, and Opinion

- Accession Document.

- Conflict in Kashmir: Selected Internet Resources by the Library, University of California, Berkeley, USA; University of California at Berkeley Library Bibliographies and Web-Bibliographies list

- Timeline since April 2003

- A peep into Kashmir History and timeline

- Conflict in Kashmir: Selected Internet Resources by the Library, University of California, Berkeley, USA; University of California at Berkeley Library Bibliographies and Web-Bibliographies list

Template:Indian foreign relations

Categories: