This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Pputter (talk | contribs) at 17:25, 8 December 2007 (→External links). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:25, 8 December 2007 by Pputter (talk | contribs) (→External links)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs attention from an expert in History. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. WikiProject History may be able to help recruit an expert. (June 2007) |

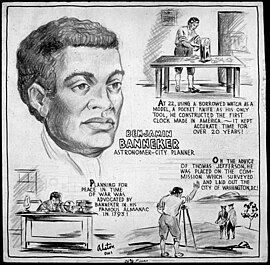

Benjamin Banneker, originally Banna Ka, or Bannakay (November 9, 1731–October 9, 1806) was a free African American mathematician, astronomer, clockmaker, and publisher.

Family history

Banneker's mother was Mary Bannaky (1710–?). Oral tradition states that her mother was a European American named Molly Walsh, who was supposedly accused of stealing a pail of milk and sent from England to the colonies as punishment. The story goes that Molly became the owner of a farm and married one of her slaves named Bannakay, whom she freed. They had four girls and Mary was the oldest.

Benjamin's father, Robert Banna Ka, was a former slave who had built a series of dams and watercourses that successfully irrigated the family farm at Ellicott's Mills, where Benjamin lived most of his life. Benjamin was taught to read and do simple arithmetic by his grandmother and by a Quaker schoolmaster, who changed his name to Banneker. Once he was old enough to help on his parents' farm, his formal education ended.

Clockmaking

At 21, Banneker saw a pocket watch that was owned by Andrew Ellicott. He was so amazed by it that Ellicott gave it to him. Banneker spent days taking it apart and reassembling it. From it Banneker then carved large-scale wooden replicas of each piece, calculating the gear assemblies himself, and used the parts to make a striking clock. The clock continued to work striking each hour for more than 50 years.

This event changed his life, and he became a watch and clockmaker. One customer was Joseph Ellicott, a Quaker surveyor, who needed an extremely accurate timepiece to make correct calculations of the locations of stars. Ellicott was so impressed with his work that he lent him books on mathematics and astronomy.

Astronomy

Banneker began his solo study of astronomy at age 58. He was able to make the calculations to predict solar and lunar eclipses and to compile an ephemeris for the Benjamin Banneker's Almanac, which an anti-slavery society published from 1792 through 1797. He became known as the Sable Astronomer.

Life

In early 1791, Andrew Ellicott hired Banneker to assist in a survey of the boundaries of the future 100 square-mile District of Columbia, which was to contain the federal capital city (the city of Washington) in the portion of the District that was northeast of the Potomac River. Because of illness and the difficulties in helping to survey at the age of 59 an extensive area that was largely wilderness, Banneker left the boundary survey in April, 1791, and returned to his home at Ellicott Mills to work on his ephemeris.

A popular urban legend erroneously describes Banneker's activities after he left the boundary survey. In 1792, President George Washington accepted the resignation of the French-American Peter (Pierre) Charles L'Enfant, who had drawn the first plans for the city of Washington but had quit out of frustration with his superiors. According to the legend, L'Enfant took his plans with him, leaving no copies behind. As the story is told, Banneker spent two days recreating the bulk of the city plans from memory. The plans that Banneker drew from his presumably photographic memory then provided the basis for the later construction of the federal capital city.

However, the legend cannot be correct. President Washington and others, including Andrew Ellicott (who, after completing the boundary survey had begun a survey of the federal city in accordance with L'Enfant's plan), also possessed copies of various versions of the plan that L'Enfant had prepared, one of which L'Enfant had sent out for printing. The U.S. Library of Congress presently owns a copy of a plan for the federal city that bears the adopted name of the plan's author, "Peter Charles L'Enfant". Furthermore, Banneker left the federal capital area and returned to Ellicott Mills in early 1791, while L'Enfant was still refining his plans for the capital city as part of his federal employment.

After departing the federal capital area, Banneker expressed a vision of social justice and equity that he wished to be adhered to in the everyday fabric of American life. He wrote to the Secretary of State and author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, a plea for justice for African Americans, calling on the colonists' personal experience as "slaves" of Britain and quoting Jefferson's own words. To support his plea, Banneker included a copy of his newly published ephemeris with its astronomical calculations. Jefferson replied to Banneker less than two weeks later in a series of statements asserting his own interest in the advancement of the equality of America's black population. Jefferson also forwarded a copy of Banneker's Almanac to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. It was also used in Britain's House of Commons. Benjamin died on October 9 1806 at age 74 in his log cabin. He never married.

Following a life journey that would be echoed by others after him including Martin Luther King Jr., and, being largely supported by European Americans who promoted racial equality and an end to racial discrimination, Banneker spent the early years of his advocacy efforts arguing specifically for the rights of American Blacks, but turned in his later years to an argument for the peaceful equality of all mankind. In 1792, Banneker included in his Almanac, a plan for the creation of a new Department in the American federal government. Several pages of Banneker's almanac outlined a Department of Peace, testifying to his ethical positions and to the need to balance a Department of War with a Department of Peace dedicated to promoting the de-escalation of national and international conflict.

Benjamin Banneker Park and Memorial, Washington, D.C.

A small urban park memorializing Benjamin Banneker is located at a prominent overlook (Banneker Circle) at the south end of L'Enfant Promenade in southwest Washington, D.C., a half mile south of the Smithsonian Institution's "Castle" on the National Mall. Although the National Park Service administers the park, the Government of the District of Columbia owns the park's site. The park, which was constructed in 1970, is now stop number 8 on Washington's Southwest Heritage Trail. In 2004, the D.C. Preservation League listed the park as one of the most endangered places in the District of Columbia. The Washington Interdependence Council is presently planning to construct a monumental memorial to Banneker at or near the site of the park. On October 26, 2006, the Council held a charrette during which a panel of judges evaluated five sculptors' proposals, one of which may become the basis of the monument. The winning design was to be revealed on November 30, 2006.

Letter to Thomas Jefferson on racism

"How pitiable it is that although you are so fully convinced of the goodness of the Father of mankind you should go against His will by detaining, by fraud and violence, so many of my brothers under groaning captivity and oppression; that you should at the same time be guilty of the most criminal act which you detest in others."

Trivia

- Although he is said to be the inventor of the first clock in America and to have made the plans of Washington D.C., this is denied in one of the only biographies of Banneker The Life Of Benjamin Banneker by Silvio Bedini.

References

- Boundary markers of the Nation's Capital : a proposal for their preservation & protection : a National Capital Planning Commission Bicentennial report. National Capital Planning Commission, Washington, DC, 1976; for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

- Bowling, Kenneth R., Creating the federal city, 1774-1800 : Potomac fever. American Institute of Architects Press, Washington, D.C., 1988

- http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri001.html Library of Congress' copy of L'Enfant's Plan

- Bedini, Silvio A., The Life of Benjamin Banneker. Scribner, New York, 1971, c1972. ISBN 0-684-12574-9

- Arnebeck, Bob, Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800. Madison Books, Lanham. Distributed by National Book Network, c1991. ISBN 0-8191-7832-2

- http://www.culturaltourismdc.org/usr_doc/SW_Heritage_Trail_brochure.pdf Brochure: Southwest Heritage Trail

- http://www.dcpreservation.org/endangered/2004/banneker.html D.C. Preservation League website: Benjamin Banneker Park

- http://www.bannekermemorial.org/specialevents.htm Washington Interdependence Council's Benjamin Banneker Memorial Prototype Charette

- Several watch and clockmakers were already established in the colony prior to the time that Banneker made the clock. In Annapolis alone there were at least four such craftsmen prior to 1750. Among these may be mentioned John Batterson, a watchmaker who moved to Annapolis in 1723; James Newberry, a watch and clockmaker who advertised in the Maryland Gazette on July 20, 1748; John Powell, a watch and clockmaker believed to have been indentured and to have been working in 1745; and Powell's master, William Roberts ... occurred at some time late in the month of April 1791.... It was not until some ten months after Banneker's departure from the scene that L'Enfant was dismissed, by means of a letter from Jefferson dated February 27, 1792. This conclusively dispels any basis for the legend that after L'Enfant's dismissal and his refusal to make available his plan of the city, Banneker recollected the plan in detail from which Ellicott was able to reconstruct it.

A more complete biography.

Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor, Astronomer, Publisher, Patriot By Charles A. Cerami (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2002) http://www.nathanielturner.com/benbanneker2.htm

External links

- Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography, edited by James Grant Wilson, John Fiske and Stanley L. Klos Six volumes, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1887-1889

- Benjamin Banneker's Trigonometry Puzzle at Convergence

- More of Benjamin Banneker's Mathematical Puzzles at Convergence

- Benjamin Banneker Historical Park & Museum

- Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum: location, hours, facilities information

- Benjamin Banneker's biography

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Benjamin Banneker", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews