This is an old revision of this page, as edited by MER-C (talk | contribs) at 12:26, 18 September 2007 (Reverted 1 edit by 58.165.146.21 identified as vandalism to last revision by SieBot.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:26, 18 September 2007 by MER-C (talk | contribs) (Reverted 1 edit by 58.165.146.21 identified as vandalism to last revision by SieBot.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this article. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Animal" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Animals Temporal range: Ediacaran - Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top-left: Loligo vulgaris (a mollusk), Chrysaora quinquecirrha (a cnidarian), Aphthona flava (an arthropod), Eunereis longissima (an annelid), and Panthera tigris (a chordate). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Opisthokonta |

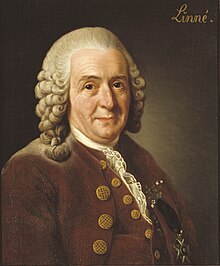

| Kingdom: | Animalia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Phyla | |

|

Subregnum Parazoa (alternatively)

| |

Animals are a major group of generally motile, multicellular organisms that feed by consuming material from other living things. Their body plan becomes fixed as they develop, usually early on in their development as embryos, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on.

The word "animal" comes from the Latin word animal, of which animalia is the plural, and is derived from anima, meaning vital breath or soul. In everyday colloquial usage, the word usually refers to non-human animals. The biological definition of the word refers to all members of the Kingdom Animalia. Therefore, when the word "animal" is used in a biological context, humans are included.

Characteristics

Animals have several characteristics that set them apart from other living things. Animals are eukaryotic and usually multicellular (although see Myxozoa), which separates them from bacteria and most protists. They are heterotrophic, generally digesting food in an internal chamber, which separates them from plants and algae. They are also distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls. All animals are motile, if only at certain life stages. Embryos pass through a blastula stage, which is a characteristic exclusive to animals.

Structure

With a few exceptions, most notably the sponges (Phylum Porifera), animals have bodies differentiated into separate tissues. These include muscles, which are able to contract and control locomotion, and nerve tissue, which sends and processes signals. There is also typically an internal digestive chamber, with one or two openings. Animals with this sort of organization are called metazoans, or eumetazoans when the former is used for animals in general.

All animals have eukaryotic cells, surrounded by a characteristic extracellular matrix composed of collagen and elastic glycoproteins. This may be calcified to form structures like shells, bones, and spicules. During development it forms a relatively flexible framework upon which cells can move about and be reorganized, making complex structures possible. In contrast, other multicellular organisms like plants and fungi have cells held in place by cell walls, and so develop by progressive growth. Also, unique to animal cells are the following intercellular junctions: tight junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes.

Reproduction and development

Nearly all animals undergo some form of sexual reproduction. Adults are diploid or polyploid. They have a few specialized reproductive cells, which undergo meiosis to produce smaller motile spermatozoa or larger non-motile ova. These fuse to form zygotes, which develop into new individuals.

Many animals are also capable of asexual reproduction. This may take place through parthenogenesis, where fertile eggs are produced without mating, or in some cases through fragmentation.

A zygote initially develops into a hollow sphere, called a blastula, which undergoes rearrangement and differentiation. In sponges, blastula larvae swim to a new location and develop into a new sponge. In most other groups, the blastula undergoes more complicated rearrangement. It first invaginates to form a gastrula with a digestive chamber, and two separate germ layers - an external ectoderm and an internal endoderm. In most cases, a mesoderm also develops between them. These germ layers then differentiate to form tissues and organs.

Most animals grow by indirectly using the energy of sunlight. Plants use this energy to convert sunlight into simple sugars using a process known as photosynthesis. Starting with the molecules carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O), photosynthesis converts the energy of sunlight into chemical energy stored in the bonds of glucose (C6H12O6) and releases oxygen (O2). These sugars are then used as the building blocks which allow the plant to grow. When animals eat these plants (or eat other animals which have eaten plants), the sugars produced by the plant are used by the animal. They are either used directly to help the animal grow, or broken down, releasing stored solar energy, and giving the animal the energy required for motion. This process is known as glycolysis.

Animals who live close to hydrothermal vents and cold seeps on the ocean floor are not dependent on the energy of sunlight. Instead, chemosynthetic archaea and eubacteria form the base of the food chain.

Origin and fossil record

Animals are generally considered to have evolved from a flagellated eukaryote. Their closest known living relatives are the choanoflagellates, collared flagellates that have a morphology similar to the choanocytes of certain sponges. Molecular studies place animals in a supergroup called the opisthokonts, which also include the choanoflagellates, fungi and a few small parasitic protists. The name comes from the posterior location of the flagellum in motile cells, such as most animal spermatozoa, whereas other eukaryotes tend to have anterior flagella.

The first fossils that might represent animals appear towards the end of the Precambrian, around 575 million years ago, and are known as the Ediacaran or Vendian biota. These are difficult to relate to later fossils, however. Some may represent precursors of modern phyla, but they may be separate groups, and it is possible they are not really animals at all. Aside from them, most known animal phyla make a more or less simultaneous appearance during the Cambrian period, about 542 million years ago. It is still disputed whether this event, called the Cambrian explosion, represents a rapid divergence between different groups or a change in conditions that made fossilization possible.

Model organisms

Because of the great diversity found in animals, it is more economical for scientists around the world concert their efforts on a small number of chosen species so that connections can be drawn from their work and conclusions extrapolated about how animals function in general. Because they are easy to keep and breed, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans have long been the most intensively studied metazoan model organism, and among the first lifeforms to be genetically sequenced. This was facilitated by the severely reduced state of their genomes, but the double-edged sword here is that with many genes, introns and linkages lost, these ecdysozoans can teach us little about the origins of animals in general. The extent of this type of evolution within the superphylum will be revealed by the crustacean, annelid, and molluscan genome projects currently in progress. Analysis of the starlet sea anemone genome has emphasised the importance of sponges, placozoans, and choanoflagellates, also being sequenced, in explaining the arrival of 1500 ancestral genes unique to the Eumetazoa.

An analyse of the homoscleromorph sponge Oscarella carmela also suggests that the last common ancestor of sponges and the eumetazoan animals were more comlex than previously assumed.

History of classification

Aristotle divided the living world between animals and plants, and this was followed by Carolus Linnaeus in the first hierarchical classification. Since then biologists have begun emphasizing evolutionary relationships, and so these groups have been restricted somewhat. For instance, microscopic protozoa were originally considered animals because they move, but are now treated separately.

In Linnaeus' original scheme, the animals were one of three kingdoms, divided into the classes of Vermes, Insecta, Pisces, Amphibia, Aves, and Mammalia. Since then the last four have all been subsumed into a single phylum, the Chordata, whereas the various other forms have been separated out. The above lists represent our current understanding of the group, though there is some variation from source to source.

See also

- Fauna

- List of animal names

- Animal behavior

- Animal rights

- List of animals by number of neurons

- Holocene extinction event

References

-

N.H. Putnam; et al. (2007). "Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization". Science. 317 (5834): 86–94. doi:10.1126/science.1139158.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mitochondrial Genome of the Homoscleromorph Oscarella carmela (Porifera, Demospongiae) Reveals Unexpected Complexity in the Common Ancestor of Sponges and Other Animals Oxford Journals

- Klaus Nielsen. Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla (2nd edition). Oxford Univ. Press, 2001.

- Knut Schmidt-Nielsen. Animal Physiology: Adaptation and Environment. (5th edition). Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997.

External links

- Tree of Life Project

- Animal Diversity Web - University of Michigan's database of animals, showing taxonomic classification, images, and other information.

- ARKive - multimedia database of worldwide endangered/protected species and common species of UK.

- Scientific American Magazine (December 2005 Issue) - Getting a Leg Up on Land About the evolution of four-limbed animals from fish.

| Elements of nature | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universe | |||||

| Earth | |||||

| Weather | |||||

| Natural environment | |||||

| Life | |||||

| See also | |||||