| Revision as of 03:18, 30 August 2013 edit99.236.199.141 (talk) Undid revision 570486233 by Bobby131313 (talk)← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:39, 30 August 2013 edit undoBobby131313 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers1,819 edits Reverted 1 edit by 99.236.199.141 (talk): Link is DEAD. (TW)Next edit → | ||

| Line 267: | Line 267: | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| {{Commons category-inline|Banknotes}} | {{Commons category-inline|Banknotes}} | ||

| {{Wikisource1911Enc|Bank-Notes}} | {{Wikisource1911Enc|Bank-Notes}}] | ||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 03:39, 30 August 2013

A banknote (often known as a bill, paper money or simply a note) is a type of negotiable instrument known as a promissory note, made by a bank, payable to the bearer on demand. When banknotes were first introduced, they were, in effect, a promise to pay the bearer in coins, but gradually became a substitute for the coins and a form of money in their own right. Banknotes were originally issued by commercial banks, but since their general acceptance as a form of money, most countries have assigned the responsibility for issuing national banknotes to a central bank. National banknotes are legal tender, meaning that medium of payment is allowed by law or recognized by a legal system to be valid for meeting a financial obligation. Historically, banks sought to ensure that they could always pay customers in coins when they presented banknotes for payment. This practice of "backing" notes with something of substance is the basis for the history of central banks backing their currencies in gold or silver. Today, most national currencies have no backing in precious metals or commodities and have value only by fiat. With the exception of non-circulating high-value or precious metal issues, coins are used for lower valued monetary units, while banknotes are used for higher values.

The idea of a using durable light-weight substance as evidence of a promise to pay a bearer on demand originated in China during the Han Dynasty in 118 BC, and was made of leather. The first known banknote was first developed in China during the Tang and Song dynasties, starting in the 7th century. Its roots were in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desired to avoid the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions. During the Yuan Dynasty, banknotes were adopted by the Mongol Empire. In Europe, the concept of banknotes was first introduced during the 13th century by travelers such as Marco Polo, with proper banknotes appearing in 17th century Sweden.

Advantages and disadvantages

| This article contains a pro and con list. Please help rewriting it into consolidated sections based on topics. (November 2012) |

Prior to the introduction of banknotes, precious or semi-precious metals minted into coins to certify their substance were widely used as a medium of exchange. The value that people attributed to coins was originally based upon the value of the metal, but over time, coins developed a value in their own right which might have differed substantially from the metal from which they were made. Banknotes were originally a claim for the coins or precious metals held by the bank, but due to the ease with which they could be transferred and the confidence that people had in the capacity of the bank to settle the notes in coins if presented, they gradually became a means of exchange in their own right. They now make up a very small proportion of the "money" that people think that they have as demand deposit bank accounts and electronic payments have negated the need to carry notes and coins.

Banknotes have a natural advantage over coins in that they are lighter to carry but are also less durable. Banknotes issued by commercial banks had counterparty risk, meaning that the bank may not be able to make payment when the note was presented. Notes issued by central banks had a theoretical risk when they were backed by gold and silver. Both banknotes and coins are subject to inflation. The durability of coins means that even if metal coins melt in a fire or are submerged under the sea for hundreds of years they still have some value when they are recovered. Gold coins salvaged from shipwrecks retain almost all of their original appearance, but silver coins slowly corrode.

Other costs of using bearer money include:

- Discounting. Before national currencies and efficient clearing houses, banknotes were only redeemable at face value at the issuing bank. Even a branch bank could discount notes of other branches of the same bank. The discounts usually increased with distance from the issuing bank. The discount also depended on the perceived safety of the bank. When banks failed the notes were usually partly redeemed out of reserves, but sometimes became worthless. The problem of discounting within a country does not exist with national currencies; however, under floating exchange rates currencies are valued relative to one another in the foreign exchange market.

- Counterfeiting paper notes has always been a problem, especially since the introduction of color photocopiers and computer image scanners. Numerous banks and nations have incorporated many types of countermeasures in order to keep the money secure; however, extremely sophisticated counterfeit notes known as superdollars have been detected in recent years.

- Manufacturing or issue costs. Coins are produced by industrial manufacturing methods that process the precious or semi-precious metals, and require additions of alloy for hardness and wear resistance. By contrast bank notes are printed paper (or polymer), and typically have a higher cost of issue, especially in larger denominations, compared with coins of the same value.

- Wear costs. Banknotes lose economic value by wear, since, even if they are in poor condition, they are still a legally valid claim on the issuing bank. However, banks of issue do have to pay the cost of replacing banknotes in poor condition and paper notes wear out much faster than coins.

- Cost of transport. Coins can be expensive to transport for high value transactions, but banknotes can be issued in large denominations that are lighter than the equivalent value in coins.

- Cost of acceptance. Coins can be checked for authenticity by weighing and other forms of examination and testing. These costs can be significant, but good quality coin design and manufacturing can help reduce these costs. Banknotes also have an acceptance cost, the costs of checking the banknote's security features and confirming acceptability of the issuing bank.

The different disadvantages between coins and banknotes imply that there may be an ongoing role for both forms of bearer money, each being used where its advantages outweigh its disadvantages.

History

Main article: History of moneyPaper currency first developed in Tang Dynasty China during the 7th century, although true paper money did not appear until the 11th century, during the Song Dynasty. The usage of paper currency later spread throughout the Mongol Empire. European explorers like Marco Polo introduced the concept in Europe during the 13th century. Paper money originated in two forms: drafts, which are receipts for value held on account, and "bills", which were issued with a promise to convert at a later date.

The perception of banknotes as money has evolved over time. Originally, money was based on precious metals. Banknotes were seen as essentially an I.O.U. or promissory note: a promise to pay someone in precious metal on presentation (see representative money). With the gradual removal of precious metals from the monetary system, banknotes evolved to represent credit money, or (if backed by the credit of a government) also fiat money.

Notes or bills were often referred to in 18th century novels and were often a key part of the plot such as a "note drawn by Lord X for £100 which becomes due in 3 months' time".

Development in China

Banknotes in the Tang Dynasty

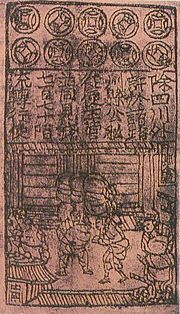

See also: List of Chinese inventionsDevelopment of the banknote began in the Tang Dynasty during the 7th century, with local issues of paper currency, although true paper money did not appear until the 11th century, during the Song Dynasty. Its roots were in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desired to avoid the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions.

Before the use of paper, the Chinese used coins that were circular, with a rectangular hole in the middle. Several coins could be strung together on a rope. Merchants in China, if they became rich enough, found that their strings of coins were too heavy to carry around easily. To solve this problem, coins were often left with a trustworthy person, and the merchant was given a slip of paper recording how much money he had with that person. If he showed the paper to that person he could regain his money. Eventually, the Song Dynasty paper money called "jiaozi" originated from these promissory notes.

Banknotes in the Song Dynasty

See also: Economy of the Song Dynasty and Jiaozi (currency)By 960 the Song Dynasty, short of copper for striking coins, issued the first generally circulating notes. A note is a promise to redeem later for some other object of value, usually specie. The issue of credit notes is often for a limited duration, and at some discount to the promised amount later. The jiaozi nevertheless did not replace coins during the Song Dynasty; paper money was used alongside the coins.

The central government soon observed the economic advantages of printing paper money, issuing a monopoly right of several of the deposit shops to the issuance of these certificates of deposit. By the early 12th century, the amount of banknotes issued in a single year amounted to an annual rate of 26 million strings of cash coins. By the 1120s the central government officially stepped in and produced their own state-issued paper money (using woodblock printing).

Even before this point, the Song government was amassing large amounts of paper tribute. It was recorded that each year before 1101 AD, the prefecture of Xinan (modern Xi-xian, Anhui) alone would send 1,500,000 sheets of paper in seven different varieties to the capital at Kaifeng. In that year of 1101, the Emperor Huizong of Song decided to lessen the amount of paper taken in the tribute quota, because it was causing detrimental effects and creating heavy burdens on the people of the region. However, the government still needed masses of paper product for the exchange certificates and the state's new issuing of paper money. For the printing of paper money alone, the Song court established several government-run factories in the cities of Huizhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Anqi.

The size of the workforce employed in these paper money factories were quite large, as it was recorded in 1175 AD that the factory at Hangzhou alone employed more than a thousand workers a day. However, the government issues of paper money were not yet nationwide standards of currency at that point; issues of banknotes were limited to regional zones of the empire, and were valid for use only in a designated and temporary limit of 3-years' time.

The geographic limitation changed between the years 1265 and 1274, when the late Southern Song government finally produced a nationwide standard currency of paper money, once its widespread circulation was backed by gold or silver. The range of varying values for these banknotes was perhaps from one string of cash to one hundred at the most. Ever since 1107, the government printed money in no less than six ink colors and printed notes with intricate designs and sometimes even with mixture of unique fiber in the paper to avoid counterfeiting.

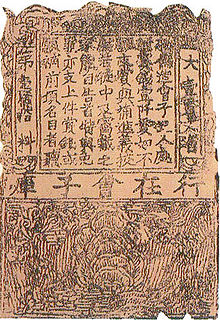

Banknotes in the Mongol Empire

The founder of the Yuan Dynasty, Kublai Khan, issued paper money known as Chao in his reign. The original notes during the Yuan Dynasty were restricted in area and duration as in the Song Dynasty, but in the later course of the dynasty, facing massive shortages of specie to fund their ruling in China, they began printing paper money without restrictions on duration.

The Venetian merchants were impressed by the fact that the Chinese paper money was guaranteed by the State and not by the private merchant or private banker as they were in the West.

Banknotes in Europe

In the 13th century, Chinese paper money became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck. Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan Dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made Into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his Country."

All these pieces of paper are, issued with as much solemnity and authority as if they were of pure gold or silver... with these pieces of paper, made as I have described, Kublai Khan causes all payments on his own account to be made; and he makes them to pass current universally over all his kingdoms and provinces and territories, and whithersoever his power and sovereignty extends... and indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan's dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold

— Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo

In medieval Italy and Flanders, because of the insecurity and impracticality of transporting large sums of cash over long distances, money traders started using promissory notes. In the beginning these were personally registered, but they soon became a written order to pay the amount to whoever had it in their possession. These notes can be seen as a predecessor to regular banknotes. The term "bank note" comes from the notes of the bank ("nota di banco") and dates from the 14th century; it originally recognized the right of the holder of the note to collect the precious metal (usually gold or silver) deposited with a banker (via a currency account). In the 14th century, it was used in every part of Europe and in Italian city-state merchants colonies outside of Europe. For international payments, the more efficient and sophisticated bill of exchange ("lettera di cambio"), that is, a promissory note based on a virtual currency account (usually a coin no longer physically existing), was used more often. All physical currencies were physically related to this virtual currency; this instrument also served as credit.

The first European banknotes were issued in 1661 by Stockholms Banco, a predecessor of the Bank of Sweden. These replaced the copper-plates being used instead as a means of payment, although in 1664 the bank ran out of coins to redeem notes and ceased operating in the same year.

The Scottish economist John Law helped establish banknotes as a formal currency in France, after the wars waged by Louis XIV left the country with a shortage of precious metals for coinage.

Banknotes in the United States

In the early 1690s, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was the first of the Thirteen Colonies to issue permanently circulating banknotes. The use of fixed denominations and printed banknotes came into use in the 18th century.

In the early 18th century, each of the thirteen colonies issued their own banknotes. During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress issued Continental currency to finance the war. The federal government of the United States did not print banknotes until 1862. However, almost immediately after adoption of the United States Constitution in 1789, the United States Congress chartered the First Bank of the United States and authorized it to issue banknotes. The bank served as a quasi-central bank of the United States. The bank closed in 1811 when Congress failed to renew its charter. In 1816, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States. When its charter expired in 1836, the bank continued to operate under a charter granted by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania until 1841.

Cotton bills of exchange were also used as money, but they were not banknotes. They were given to planters in exchange for their cotton, but were not paid in gold or notes until the cotton was sold in Liverpool. Any deficiency would reduce the amount to be paid on the bill of exchange. The bills were redeemable when notice was sent back to the United States. In the meantime the bill of exchange holder could trade the note at a discount, and the notes circulated as money.

In the early history of the United States there was no national currency and an insufficient supply of coinage. Banknotes were the majority of the money in circulation. During financial crises many banks failed and their notes often were paid out of reserves, often below par value, but sometimes the notes were worthless. Also, banknotes were discounted relative to gold and silver, the discount depending on the financial strength of the bank.

The Confederate Congress met in Montgomery, Alabama on 9 March 1861 and authorized the issuing of paper currency (in the form of interest-bearing notes). Such notes were originally printed by the National Bank Note Co.

In the United States, public acceptance of banknotes in replacement of precious metals was hastened in part by Executive Order 6102 in 1933. This order, which never actually led to anyone being imprisoned, carried the threat of a maximum $10,000 fine and a maximum of ten years in prison for anyone who kept more than $100 of gold in preference to banknotes.

Issue of banknotes

Generally, a central bank or treasury is solely responsible within a state or currency union for the issue of banknotes. However, this is not always the case, and historically the paper currency of countries was often handled entirely by private banks. Thus, many different banks or institutions may have issued banknotes in a given country. In the United States, commercial banks were authorized to issue banknotes from 1863 to 1935. In the last of these series, the issuing bank would stamp its name and promise to pay, along with the signatures of its president and cashier on a preprinted note. By this time, the notes were standardized in appearance and not too different from Federal Reserve Notes.

In a small number of countries, private banknote issue continues to this day. For example, by virtue of the complex constitutional setup in the United Kingdom, certain commercial banks in two of the union's four constituent countries (Scotland and Northern Ireland) continue to print their own banknotes for domestic circulation, even though they are not fiat money or declared in law as legal tender anywhere. The UK's central bank, the Bank of England, prints notes which are legal tender in England and Wales; these notes are also usable as money (but not legal tender) in the rest of the UK (see Banknotes of the pound sterling).

In Hong Kong, three commercial banks are licenced to issue Hong Kong dollar notes. As well as commercial issuers, other organizations may have note-issuing powers; for example, until 2002 the Singapore dollar was issued by the Board of Commissioners of Currency Singapore, a government agency which was later taken over by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

Materials used for banknotes

Paper banknotes

Most banknotes are made from cotton paper (see also paper) with a weight of 80 to 90 grams per square meter. The cotton is sometimes mixed with linen, abaca, or other textile fibres. Generally, the paper used is different from ordinary paper: it is much more resilient, resists wear and tear (the average life of a banknote is two years), and also does not contain the usual agents that make ordinary paper glow slightly under ultraviolet light. Unlike most printing and writing paper, banknote paper is infused with polyvinyl alcohol or gelatin, instead of water, to give it extra strength. Early Chinese banknotes were printed on paper made of mulberry bark. Mitsumata (Edgeworthia chrysantha) and other fibers are used in Japanese banknote paper (a kind of Washi).

Most banknotes are made using the mould made process in which a watermark and thread is incorporated during the paper forming process. The thread is a simple looking security component found in most banknotes. It is however often rather complex in construction comprising fluorescent, magnetic, metallic and micro print elements. By combining it with watermarking technology the thread can be made to surface periodically on one side only. This is known as windowed thread and further increases the counterfeit resistance of the banknote paper. This process was invented by Portals, part of the De La Rue group in the UK. Other related methods include watermarking to reduce the number of corner folds by strengthening this part of the note, coatings to reduce the accumulation of dirt on the note, and plastic windows in the paper that make it very hard to copy.

Counterfeiting and security measures on paper banknotes

The ease with which paper money can be created, by both legitimate authorities and counterfeiters, has led both to a temptation in times of crisis such as war or revolution to produce paper money which was not supported by precious metal or other goods, thus leading to Hyperinflation and a loss of faith in the value of paper money, e.g. the Continental Currency produced by the Continental Congress during the American Revolution, the Assignats produced during the French Revolution, the paper currency produced by the Confederate States of America and the Individual States of the Confederate States of America, the financing of World War I by the Central Powers (by 1922 1 gold Austro-Hungarian krone of 1914 was worth 14,400 paper Kronen), the devaluation of the Yugoslav Dinar in the 1990s, etc. Banknotes may also be overprinted to reflect political changes that occur faster than new currency can be printed.

In 1988, Austria produced the 5000 Schilling banknote (Mozart), which is the first foil application (Kinegram) to a paper banknote in the history of banknote printing. The application of optical features is now in common use throughout the world.

Many countries' banknotes now have embedded holograms.

Polymer banknotes

In 1983, Costa Rica and Haiti issued the first Tyvek and the Isle of Man issued the first Bradvek polymer (or plastic) banknotes; these were printed by the American Banknote Company and developed by DuPont. These early plastic notes were plagued with issues such as ink wearing off and were discontinued. In 1988, after significant research and development in Australia by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the Reserve Bank of Australia, Australia produced the first polymer banknote made from biaxially-oriented polypropylene (plastic), and in 1996 became the first country to have a full set of circulating polymer banknotes of all denominations completely replacing its paper banknotes. Since then, other countries to adopt circulating polymer banknotes include Bangladesh, Brazil, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, Mexico, Nepal, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Romania, Samoa, Singapore, the Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, and Zambia, with other countries issuing commemorative polymer notes, including China, Kuwait, the Northern Bank of Northern Ireland, Taiwan and Hong Kong. Another country indicating plans to issue polymer banknotes is Nigeria. In 2005, Bulgaria issued the world's first hybrid paper-polymer banknote.

Polymer banknotes were developed to improve durability and prevent counterfeiting through incorporated security features, such as optically variable devices that are extremely difficult to reproduce.

Other materials

Over the years, a number of materials other than paper have been used to print banknotes. This includes various textiles, including silk, and materials such as leather.

Silk and other fibers have been commonly used in the manufacture of various banknote papers, intended to provide both additional durability and security. Crane and Company patented banknote paper with embedded silk threads in 1844 and has supplied paper to the United States Treasury since 1879. Banknotes printed on pure silk "paper" include "emergency money" Notgeld issues from a number of German towns in 1923 during a period of fiscal crisis and hyperinflation. Most notoriously, Bielefeld produced a number of silk, leather, velvet, linen and wood issues, and although these issues were produced primarily for collectors, rather than for circulation, they are in demand by collectors. Banknotes printed on cloth include a number of Communist Revolutionary issues in China from areas such as Xinjiang, or Sinkiang, in the United Islamic Republic of East Turkestan in 1933. Emergency money was also printed in 1902 on khaki shirt fabric during the Boer War.

Leather banknotes (or coins) were issued in a number of sieges, as well as in other times of emergency. During the Russian administration of Alaska, banknotes were printed on sealskin. A number of 19th century issues are known in Germanic and Baltic states, including the places of Dorpat, Pernau, Reval, Werro and Woiseck. In addition to the Bielefeld issues, other German leather Notgeld from 1923 is known from Borna, Osterwieck, Paderborn and Pößneck.

Other issues from 1923 were printed on wood, which was also used in Canada in 1763–1764 during Pontiac's Rebellion, and by the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1848, in Bohemia, wooden checkerboard pieces were used as money.

Even playing cards were used for currency in France in the early 19th century, and in French Canada from 1685 until 1757, in the Isle of Man in the beginning of the 19th century, and again in Germany after World War I.

Vertical orientation

Vertical currency is a type of currency in which the orientation has been changed from the conventional horizontal to a vertical orientation. Dowling Duncan, a self-touted multidisciplinary design studio, conducted a study in which they determined people tend to handle and deal with money vertically rather than horizontally, especially when currency is processed through ATM and other money machines. They also note how money transactions are conducted vertically not horizontally. Bermuda, Colombia, Israel and Switzerland have adopted vertically oriented currency.

Vending machines and banknotes

People are not the only economic actors who are required to accept banknotes. In the late 20th century vending machines were designed to recognize banknotes of the smaller values long after they were designed to recognize coins distinct from slugs. This capability has become inescapable in economies where inflation has not been followed by introduction of progressively larger coin denominations (such as the United States, where several attempts to make dollar coins popular in general circulation have largely failed). The existing infrastructure of such machines presents one of the difficulties in changing the design of these banknotes to make them less counterfeitable, that is, by adding additional features so easily discernible by people that they would immediately reject banknotes of inferior quality, for every machine in the country would have to be updated.

Destruction

See also: Money burningBanknotes last on an average of three years until they are no longer fit for circulation, after which they are collected for destruction, usually recycling or shredding. A banknote is removed from the money supply by banks or other financial institutions because of everyday wear and tear from its handling. Banknote bundles are passed through a sorting machine that determines whether a particular note needs to be shredded, or are removed from the supply chain by a human inspector if they are deemed unfit for continued use – for example, if they are mutilated or torn. Counterfeit banknotes are destroyed unless they are needed for evidentiary or forensic purposes.

Contaminated banknotes are also decommissioned. A Canadian government report indicates:

Types of contaminants include: notes found on a corpse, stagnant water, contaminated by human or animal body fluids such as urine, feces, vomit, infectious blood, fine hazardous powders from detonated explosives, dye pack and/or drugs...

These are removed from circulation primarily to prevent the spread of diseases.

When taken out of circulation, Australian Plastic/Polymer bank notes are melted down and mixed together to form plastic garbage bins.

Intelligent Banknote Neutralisation System (IBNS)

Intelligent Banknote Neutralisation System (IBNS) is a security system which renders banknotes unusable by marking them permanently as stolen with a degradation agent. Marked (stained) banknotes cannot be brought back into circulation easily and can be linked to the crime scene. Today's most used degradation agent is a special security ink which cannot be removed from the banknote easily and not without destroying the banknote itself, but other agents also exist. Today IBNS are used to protect banknotes in ATM's, Retail Machines and during cash-in-transit operations.

Confiscation and asset forfeiture

In the United States there are many laws that allow the confiscation of cash and other assets from the bearer if there is suspicion that the money came from an illegal activity. Because a significant amount of U.S. currency contains traces of cocaine and other illegal drugs, it is not uncommon for innocent people searched at airports or stopped for traffic violations to have cash in their possession sniffed by dogs for drugs and then have the cash seized because the dog smelled drugs on the money. It is then up to the owner of the money to prove where the cash came from at his own expense. Many people simply forfeit the money. In 1994, the United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, held in the case of UNITED STATES of America v. U.S. CURRENCY, $30,060.00 (39 F.3d 1039 63 USLW 2351, No. 92-55919) that the widespread presence of illegal substances on paper currency in the Los Angeles area created a situation where the reaction of a drug-sniffing dog would not create probable cause for civil forfeiture.

Displacement by electronic currency

Banknotes have increasingly been displaced by credit and debit cards and electronic money transfers. Some governments, such as Canada, are considering replacing paper notes and coins with digital currency. Sweden has begun implementing digital currency.

Paper money collecting as a hobby

Banknote collecting, or Notaphily, is a slowly growing area of numismatics. Although generally not as widespread as coin and stamp collecting, the hobby is slowly expanding. Prior to the 1990s, currency collecting was a relatively small adjunct to coin collecting, but the practice of currency auctions, combined with larger public awareness of paper money, has caused more interest in and valuation of rare banknotes.

Since 2007 Sanjay Relan, of Hong Kong, has held the Guinness world record for collecting 221 banknotes representing 221 different countries. For a short period in 2007, he also held the Guinness world record for collecting 235 coins representing 235 different countries.

Trades

For years, the mode of collecting banknotes was through a handful of mail order dealers who issued price lists and catalogs. In the early 1990s, it became more common for rare notes to be sold at various coin and currency shows via auction. The illustrated catalogs and "event nature" of the auction practice seemed to fuel a sharp rise in overall awareness of paper money in the numismatic community. The emergence of currency third party grading services (similar to services that grade and "slab", or encapsulate, coins) also may have increased collector and investor interest in notes. Entire advanced collections are often sold at one time, and to this day single auctions can generate millions in gross sales. Today, eBay has surpassed auctions in terms of highest volume of sales of banknotes although the risk of counterfeit is extremely high. However, rare banknotes still sell for much less than comparable rare coins. This disparity is diminishing as paper money prices continue to rise. Many rare and historical banknotes have sold for more than a million dollars.

There are many different organizations and societies around the world for the hobby, including the International Bank Note Society (IBNS) which currently assert to have around 2,000 members in 90 countries.

Novelty

The universal appeal and instant recognition of bank notes has resulted in a plethora of novelty merchandise that designed to have the appearance of paper currency. These items cover nearly every class of product. Cloth material printed with bank note patterns is used for clothing, bed linens, curtains, upholster and more. Acrylic paperweights and even toilet seats with bank notes embedded inside are also common. Items that resemble stacks of bank notes can be used as a seat or ottoman are also available.

Manufactures of these items must take into consideration when creating these products is if the product could be construed as counterfeiting. Overlapping note images and/or changing the dimensions of the reproduction to be at least 50% smaller or 50% larger than the original is one way to avoid the risk of being considered a counterfeit. But in cases where realism is the goal, other steps may be necessary. For example, in the stack of bank notes seat mentioned earlier, the decal used to create the product would be considered counterfeit. However, once the decal has been affixed to the resin stack shell and cannot be peeled off, the final product is no longer at risk of being classified as counterfeit, even though the resulting appearance is so realistic.

See also

|

References

- "Legal Tender Guidelines". British Royal Mint. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- The History of Money. WGBH Educational Foundation. Accessed 25 April 2012.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais (2006), 156.

- ^ Bowman (2000), 105.

- ^ Gernet (1962), 80.

- ^ William N. Goetzmann; K. Geert Rouwenhorst (1 August 2005). The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-19-517571-4.

The Mongols adopted the Jin and Song practice of issuing paper money, and the earliest European account of paper money is the detailed description given by Marco Polo, who claimed to have served at the court of the Yuan dynasty rulers.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Marco Polo (1818). The Travels of Marco Polo, a Venetian, in the Thirteenth Century: Being a Description, by that Early Traveller, of Remarkable Places and Things, in the Eastern Parts of the World. pp. 353–355. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Famous shipwrecks from which valuable precious metals and coins were recovered in recent years include the Atocha and the SS Central America. Shipwreck coins are highly collectible and dealers post photos on the internet.

- Shipwreck and hoard map

- ^ Taylor, George Rogers (1951). The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. New York, Toronto: Rinehart & Co. ISBN 978-0-87332-101-3. Cite error: The named reference "Taylor 1951" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Peter Bernholz (2003). Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-84376-155-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Daniel R. Headrick (1 April 2009). Technology: A World History. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-988759-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Ebrey et al., 156.

- ^ Gernet, 80.

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 47.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 48.

- Moshenskyi, Sergii (2008). History of the weksel: Bill of exchange and promissory note. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4363-0694-2.

- De Geschiedenis van het Geld (the History of Money), 1992, Teleac, page 96

- Geisst, Charles R. (2005). Encyclopedia of American business history. New York. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8160-4350-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Karl Gunnar Persson - An Economic History of Europe: Knowledge, Institutions and Growth, 600 to the Present Cambridge University Press, 28 January 2010 , ISBN 052154940X - Retrieved 2012-06-03

- Taylor 1951, pp. 317 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTaylor1951 (help)

-

North, Douglas C. (1966). The Economic Growth of the United States 1790-1860. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00346-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - How Gold Coins Circulated in 19 th Century America David Ginsburg

- Today in History: 9 March | Richmond Times-Dispatch

- ^ Bank for International Settlements. "The Role of Central Bank Money in Payment Systems" (PDF). pp. 96, and see also page 9: "The coexistence of central and commercial bank monies: multiple issuers, one currency". Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

Although historically not the case, these days banknotes are usually issued only by the central bank. This is broadly the case in all CPSS economies, except Hong Kong SAR, where banknotes are issued by three commercial banks. Singapore and the United Kingdom are more limited exceptions. Singapore dollar banknotes have been issued by the Board of Currency Commissioners, a government agency, although following the merger of the Board into the MAS in October 2002 this is no longer the case. In the United Kingdom, Scottish banks retain the right to issue banknotes alongside those of the Bank of England and three banks currently still do so.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "DeLaRue – The Banknote Lifecycle – from Design to Destruction"

- National Printing Bureau - Introduction of Banknotes - Banknote Production Process - Paper Production Process

- "About Australia: Our Currency". Our Currency. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - 14 August 2012 23:42 (14 August 2010). "Dowling | Duncan – Dowling Duncan redesign the US bank notes". Dowlingduncan.com. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Facts About U.S. Money". Money. http://www.factmonster.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Trichur, Rita (28 September 2007). "Bankers wipe out dirty money". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Rhodes, Trissie. "Australian Polymer Banknotes". http://www.therightnote.com.au. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - International Society for Individual Liberty

- News story

- http://bulk.resource.org/courts.gov/c/F3/39/39.F3d.1039.92-55919.html

- Strange, Adario (13 April 2012). "Canada Asks Developers to Create Digital Currency". PC Magazine.

- Malin Rising (17 March 2012). "In Sweden, cash is king no more - Yahoo! News". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "Paper Money Collecting as a Hobby". Banknote.pro. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- "You Won a Lottery, Got an Award, or a Mystery Shopper Job and They Sent You a Check! Counterfeit Cashiers Checks". Consumer Fraud Report. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- "Forged German Treasure Banknotes". mebanknotes. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Cyndy Aleo-Carreira (25 March 2009). "2 Million Counterfeit Items Removed From EBay". PC World. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- "Most expensive Australian banknote". World Record Academy. 30 November. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Introducing the IBNS". IBNS. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

Further references

- Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231110049

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0618133844

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521875668

External links

![]() Media related to Banknotes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Banknotes at Wikimedia Commons