| Revision as of 22:01, 25 October 2011 editSkyLined (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers4,580 editsm →Physical gravity wells: fix φ => Φ← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:02, 25 October 2011 edit undoSkyLined (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers4,580 editsm →The rubber-sheet model: inline math => unicode/htmlNext edit → | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

| Consider an idealized rubber sheet suspended in a uniform gravitational field normal to the sheet. In equilibrium, the elastic ] in each part of the sheet must be equal and opposite to the gravitational pull on that part of the sheet; that is, | Consider an idealized rubber sheet suspended in a uniform gravitational field normal to the sheet. In equilibrium, the elastic ] in each part of the sheet must be equal and opposite to the gravitational pull on that part of the sheet; that is, | ||

| :<math>k \nabla^2 h = -g \rho</math> | :<math>k \nabla^2 h = -g \rho</math> | ||

| where ''k'' is the ] of the rubber, |

where ''k'' is the ] of the rubber, h(x) is the upward displacement of the sheet (assumed to be small), ''g'' is the strength of the gravitational field, and ρ(x) is the mass density of the sheet. The mass density may be viewed as intrinsic to the sheet or as belonging to objects resting on top of the sheet. | ||

| This equilibrium condition is identical in form to the gravitational ] | This equilibrium condition is identical in form to the gravitational ] | ||

| :<math>\nabla^2 \Phi = - 4 \pi G \rho</math> | :<math>\nabla^2 \Phi = - 4 \pi G \rho</math> | ||

| where |

where Φ(x) is the gravitational potential and ρ(x) is the mass density. Thus, to a first approximation, a massive object placed on a rubber sheet will deform the sheet into a correctly shaped gravity well, and (as in the rigid case) a second test object placed near the first will gravitate toward it in an approximation of the correct force law. More generally, a collection of objects placed on the sheet will mutually gravitate in roughly the way predicted by Newton's law of gravitation.{{Citation needed|date=January 2011}} | ||

| This model is somewhat less suited to classroom demonstration than the rigid gravity well because a physical two-dimensional rubber sheet will deform according to the two-dimensional analogue of Newtonian gravity, which has a 1/r force law. To obtain the correct 1/r² force law, one needs a three-dimensional rubber sheet bending into a fourth spatial dimension.{{Citation needed|date=January 2011}} | This model is somewhat less suited to classroom demonstration than the rigid gravity well because a physical two-dimensional rubber sheet will deform according to the two-dimensional analogue of Newtonian gravity, which has a 1/r force law. To obtain the correct 1/r² force law, one needs a three-dimensional rubber sheet bending into a fourth spatial dimension.{{Citation needed|date=January 2011}} | ||

Revision as of 22:02, 25 October 2011

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Gravity well" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (July 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

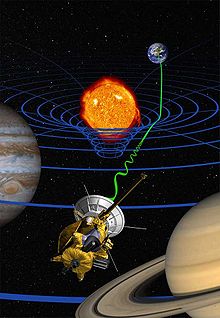

A gravity well or gravitational well is a conceptual model of the gravitational field surrounding a body in space. The more massive the body the deeper and more extensive the gravity well associated with it. The Sun has a far-reaching and deep gravity well. Asteroids and small moons have much shallower gravity wells. Anything on the surface of a planet or moon is considered to be at the bottom of the gravity well. Entering space from the surface of a planet or moon means climbing out of the gravity well. The deeper a planet or moon's gravity well is, the more energy it takes to achieve escape velocity.

In astrophysics, a gravity well is specifically the gravitational potential field around a massive body. Other types of potential wells include electrical and magnetic potential wells. Physical models of gravity wells are sometimes used to illustrate orbital mechanics. Gravity wells are frequently confused with general relativistic embedding diagrams, but the two concepts are unrelated.

Details

The external gravitational potential of a spherically symmetric body of mass M is given by the formula:

A plot of this function in two dimensions is shown in the figure. This plot has been completed with an interior potential proportional to |x|, corresponding to an object of uniform density, but this interior potential is generally irrelevant since the orbit of a test particle cannot intersect the body.

The potential function has a hyperbolic cross section; the sudden dip in the center is the origin of the name "gravity well." A black hole would not have this "closing" dip.

Physical gravity wells

In a uniform gravitational field, the gravitational potential at a point is proportional to the height. Thus if the graph of a gravitational potential Φ(x,y) is constructed as a physical surface and placed in a uniform gravitational field so that the actual field points in the −Φ direction, then each point on the surface will have an actual gravitational potential proportional to the value of Φ at that point. As a result, an object constrained to move on the surface will have roughly the same equation of motion as an object moving in the potential field Φ itself. Gravity wells constructed on this principle can be found in many science museums.

There are several sources of inaccuracy in this model:

- The friction between the object and the surface has no analogue in vacuum. This effect can be reduced by using a rolling ball instead of a sliding block.

- The object's vertical motion contributes to its kinetic energy, and has no analogue in vacuum. This effect can be reduced by making the gravity well shallower (i.e. by choosing a smaller scaling factor for the Φ axis).

- A rolling ball's rotational kinetic energy has no analogue in vacuum. This effect can be reduced by concentrating the ball's mass near its center so that the moment of inertia is small compared to mr².

- A ball's center of mass is not located on the surface but at a fixed distance r, which changes its potential energy by an amount depending on the slope of the surface at that point. For balls of a fixed size, this effect can be eliminated by constructing the surface so that the center of the ball, rather than the surface itself, lies on the graph of Φ.

The rubber-sheet model

Consider an idealized rubber sheet suspended in a uniform gravitational field normal to the sheet. In equilibrium, the elastic tension in each part of the sheet must be equal and opposite to the gravitational pull on that part of the sheet; that is,

where k is the elastic constant of the rubber, h(x) is the upward displacement of the sheet (assumed to be small), g is the strength of the gravitational field, and ρ(x) is the mass density of the sheet. The mass density may be viewed as intrinsic to the sheet or as belonging to objects resting on top of the sheet. This equilibrium condition is identical in form to the gravitational Poisson equation

where Φ(x) is the gravitational potential and ρ(x) is the mass density. Thus, to a first approximation, a massive object placed on a rubber sheet will deform the sheet into a correctly shaped gravity well, and (as in the rigid case) a second test object placed near the first will gravitate toward it in an approximation of the correct force law. More generally, a collection of objects placed on the sheet will mutually gravitate in roughly the way predicted by Newton's law of gravitation.

This model is somewhat less suited to classroom demonstration than the rigid gravity well because a physical two-dimensional rubber sheet will deform according to the two-dimensional analogue of Newtonian gravity, which has a 1/r force law. To obtain the correct 1/r² force law, one needs a three-dimensional rubber sheet bending into a fourth spatial dimension.

Gravity wells and general relativity

Both the rigid gravity well and the rubber-sheet model are frequently misidentified as models of general relativity, due to an accidental resemblance to general relativistic embedding diagrams, and perhaps Einstein's employment of gravitational "curvature" bending the path of light, which he described as a prediction of general relativity. In particular, the embedding diagram most commonly found in textbooks (an isometric embedding of a constant-time equatorial slice of the Schwarzschild metric in Euclidean 3-dimensional space) superficially resembles a gravity well.

Embedding diagrams are, however, fundamentally different from gravity wells in a number of ways. Most importantly, an embedding is merely a shape, while a potential plot has a distinguished "downward" direction; thus turning a gravity well "upside down" (by negating the potential) turns the attractive force into a repulsive force, while turning a Schwarzschild embedding upside down (by rotating it) has no effect, since it leaves its intrinsic geometry unchanged. Geodesics on the Schwarzschild surface do bend toward the central mass like a ball rolling in a gravity well, but for entirely different reasons. There is no analogue of the Schwarzschild embedding for a repulsive field: while such a field can be modeled in general relativity, the spatial geometry cannot be embedded in three dimensions.

The Schwarzschild embedding is commonly drawn with a hyperbolic cross section like the potential well, but in fact it has a parabolic cross section which, unlike the gravity well, does not approach a planar asymptote. See Flamm's paraboloid.

. In this case, M = 100 000 kg, G = -6.67E-11

. In this case, M = 100 000 kg, G = -6.67E-11