| Revision as of 17:01, 24 April 2011 view sourceYogesh Khandke (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,597 edits →Pollution and ecology: Well cited, but unrelated information deleted← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:12, 24 April 2011 view source Snowded (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers37,634 edits Restore reference deleted for no reasonNext edit → | ||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

| The Ganges is the most sacred river to Hindus and is also a lifeline to millions of Indians who live along its course and depend on it for their daily needs.<ref>http://www.zeenews.com/news587747.html</ref> It is worshiped as the goddess '']'' in ].<ref>, by Sukumari Bhattacharji, Ramananda Bandyopadhyay, p. 54</ref> It has also been important historically: many former provincial or imperial capitals (such as ]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=law3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA334&lpg=PA334&dq=patliputra+ganga+Maurya+capital&source=bl&ots=Wv2uHWbYbj&sig=d6xjgueBEtEG610yTObwt8q-qgM&hl=en&ei=W3WsTbu5E4uurAf7_oWoCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology By A. Ghosh page 334</ref>, ]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=law3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA334&lpg=PA334&dq=patliputra+ganga+Maurya+capital&source=bl&ots=Wv2uHWbYbj&sig=d6xjgueBEtEG610yTObwt8q-qgM&hl=en&ei=W3WsTbu5E4uurAf7_oWoCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=kannauj&f=false An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology By A. Ghosh page 199</ref>, ], ], ], ] and ]) have been located on its banks. | The Ganges is the most sacred river to Hindus and is also a lifeline to millions of Indians who live along its course and depend on it for their daily needs.<ref>http://www.zeenews.com/news587747.html</ref> It is worshiped as the goddess '']'' in ].<ref>, by Sukumari Bhattacharji, Ramananda Bandyopadhyay, p. 54</ref> It has also been important historically: many former provincial or imperial capitals (such as ]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=law3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA334&lpg=PA334&dq=patliputra+ganga+Maurya+capital&source=bl&ots=Wv2uHWbYbj&sig=d6xjgueBEtEG610yTObwt8q-qgM&hl=en&ei=W3WsTbu5E4uurAf7_oWoCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology By A. Ghosh page 334</ref>, ]<ref>http://books.google.com/books?id=law3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA334&lpg=PA334&dq=patliputra+ganga+Maurya+capital&source=bl&ots=Wv2uHWbYbj&sig=d6xjgueBEtEG610yTObwt8q-qgM&hl=en&ei=W3WsTbu5E4uurAf7_oWoCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=kannauj&f=false An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology By A. Ghosh page 199</ref>, ], ], ], ] and ]) have been located on its banks. | ||

| The Ganges ranks among the top five most polluted rivers of the world. Pollution threatens not only humans, but also more than 140 fish species, 90 amphibian species and the endangered Ganges river dolphin.<ref name=greendiary>http://www.greendiary.com/entry/ganga-is-dying-at-kanpur/</ref> The ], an environmental initiative to clean up the river, has been a major failure thus far,<ref name=haberman/><ref name=gardner/><ref name=cleanperish>, '']'', Mar 19, 2010</ref> due to corruption and lack of technical expertise,<ref name=sheth/> lack of good environmental planning,<ref name=singh/> Indian traditions and beliefs,<ref name=tiwari/> and lack of support from religious authorities.<ref name=puttick3/> | The Ganges ranks among the top five most polluted rivers of the world<ref name=greendiary/> with ] levels in the river near ] more than hundred times the official Indian government limits.<ref name=economist2008-ganges-pollution/>. Pollution threatens not only humans, but also more than 140 fish species, 90 amphibian species and the endangered Ganges river dolphin.<ref name=greendiary>http://www.greendiary.com/entry/ganga-is-dying-at-kanpur/</ref> The ], an environmental initiative to clean up the river, has been a major failure thus far,<ref name=haberman/><ref name=gardner/><ref name=cleanperish>, '']'', Mar 19, 2010</ref> due to corruption and lack of technical expertise,<ref name=sheth/> lack of good environmental planning,<ref name=singh/> Indian traditions and beliefs,<ref name=tiwari/> and lack of support from religious authorities.<ref name=puttick3/> | ||

| ==Course== | ==Course== | ||

Revision as of 17:12, 24 April 2011

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (April 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Template:Geobox The Ganges (/ˈɡændʒiːz/ GAN-jeez;) or Ganga, (Template:Lang-sa Template:Lang-hi Template:Lang-ur Ganga Template:IPA-hns; Template:Lang-bn Gônga), is a trans-boundary river of India and Bangladesh. The 2,525 km (1,569 mi) river rises in the western Himalayas in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, and flows south and east through the Gangetic Plain of North India into Bangladesh, where it empties into the Bay of Bengal. By discharge it ranks among the world's top 20 rivers.

The Ganges is the most sacred river to Hindus and is also a lifeline to millions of Indians who live along its course and depend on it for their daily needs. It is worshiped as the goddess Ganga in Hinduism. It has also been important historically: many former provincial or imperial capitals (such as Patliputra, Kannauj, Kara, Allahabad, Murshidabad, Baharampur and Kolkata) have been located on its banks.

The Ganges ranks among the top five most polluted rivers of the world with fecal coliform levels in the river near Varanasi more than hundred times the official Indian government limits.. Pollution threatens not only humans, but also more than 140 fish species, 90 amphibian species and the endangered Ganges river dolphin. The Ganga Action Plan, an environmental initiative to clean up the river, has been a major failure thus far, due to corruption and lack of technical expertise, lack of good environmental planning, Indian traditions and beliefs, and lack of support from religious authorities.

Course

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Ganges" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Ganges proper begins at the confluence of the Bhagirathi and Alaknanda rivers. The Bhagirathi is considered to be the true source in Hindu culture and mythology, although the Alaknanda is longer. Although many small streams comprise the headwaters of the Ganges, the six longest and their five confluences are culturally significant. The headwaters of the Alaknanda are formed by snowmelt from such peaks as Nanda Devi, Trisul, and Kamet. The Alaknanda meets the Dhauliganga River at Vishnuprayag, the Nandakini River at Nandprayag, the Pindar River at Karnaprayag, the Mandakini River at Rudraprayag, and finally the Bhagirathi River at Devprayag. The Bhagirathi rises at the foot of Gangotri Glacier, at Gaumukh, at an elevation of 3,892 m (12,769 ft).

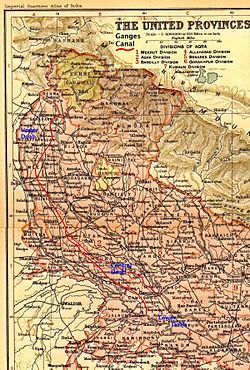

After flowing 200 kilometres (120 mi) through its narrow Himalayan valley, the Ganges debouches onto the Gangetic Plain at the pilgrimage town of Haridwar, Uttarakhand. There, a dam diverts some of its waters into the Ganges Canal, which irrigates the Doab region of Uttar Pradesh, whereas the river, whose course has been roughly southwest until this point, now begins to flow southeast through the plains of northern India.

The Ganges follows an 800-kilometre (500 mi) arching course passing through the cities of Kannauj, Farukhabad, and Kanpur before being joined from the southwest by the Yamuna at the Sangam at Allahabad, a holy confluence in Hinduism. At their confluence the Yamuna is larger than the Ganges, contributing about 58.5% of the combined flow.

Now flowing east, the river meets the Gomti, the Ghaghra, the Gandaki, and the Kosi on the left bank; and the Son on the right, and gathers a formidable current between Allahabad and Malda, West Bengal. Along the way, it passes the towns of Varanasi, Patna, Ghazipur, Bhagalpur, Mirzapur, Ballia, Buxar, Saidpur, and Chunar. At Bhagalpur, the river begins to flow south-southeast and at Pakur, it begins its attrition with the branching away of its first distributary, the Bhāgirathi-Hooghly, which goes on to become the Hooghly River. Just before the border with Bangladesh the Farakka Barrage, controls the flow of the Ganges, diverting some of the water into a feeder canal linking to the Hooghly to keep it relatively silt-free.

After entering Bangladesh, the main branch of the Ganges is known as the Padma until it is joined by the Jamuna River, the largest distributary of the Brahmaputra. Further downstream, the Ganges is fed by the Meghna River, the second largest distributary of the Brahmaputra, and takes on the Meghna's name as it enters the Meghna Estuary. Fanning out into the 350-kilometre (220 mi)-wide Ganges Delta, the river finally empties into the Bay of Bengal.

Only the Amazon has a greater discharge than the combined flow of the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Surma-Meghna river system.

Geology

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Snowded (talk | contribs) 13 years ago. (Update timer) |

Hydrology

The hydrology of the Ganges River is very complicated, especially in the Ganges Delta region. One result is different ways to determine the river's length, its discharge, and the size of its drainage basin. The name Ganges is used for the river between the confluence of the Bhagirathi and Alaknanda rivers, in the Himalayas, and the India-Bangladesh border, near the Farakka Barrage and the first bifurcation of the river. The length of the Ganges is frequently said to be slightly over 2,500 km (1,600 mi) long, about 2,505 km (1,557 mi), to 2,525 km (1,569 mi), or perhaps 2,550 km (1,580 mi). In these cases the river's source is usually assumed to be the source of the Bhagirathi River, Gangotri Glacier at Gomukh, and its mouth being the mouth of the Meghna River on the Bay of Bengal. Sometimes the source of the Ganges is considered to be at Haridwar, where its Himalayan headwater streams debouch onto the Gangetic Plain.

In some cases, the length of the Ganges is given for its Hooghly River distributary, which is longer than its main outlet via the Meghna River, resulting in a total length of about 2,620 km (1,630 mi), from the source of the Bhagirathi, or 2,135 km (1,327 mi), from Haridwar to the Hooghly's mouth. In other cases the length is said to be about 2,240 km (1,390 mi), from the source of the Bhagirathi to the Bangladesh border, where its name changes to Padma.

For similar reasons, sources differ over the size of the river's drainage basin. The Ganges basin, including the delta but not the Brahmaputra or Meghna basins, is about 1,080,000 km (420,000 sq mi), of which 861,000 km (332,000 sq mi) are in India (about 80%), 140,000 km (54,000 sq mi) in Nepal (13%), 46,000 km (18,000 sq mi) in Bangladesh (4%), and 33,000 km (13,000 sq mi) in China (3%). Sometimes the Ganges and Brahmaputra–Meghna drainage basins are combined for a total of about 1,600,000 km (620,000 sq mi), or 1,621,000 km (626,000 sq mi).

The discharge of the Ganges also differs by source. Frequently, discharge is described for the mouth of the Meghna River, thus combining the Ganges with the Brahmaputra and Meghna. This results in a total average annual discharge of about 38,000 m/s (1,300,000 cu ft/s). In other cases the average annual discharges of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna are given separately, at about 16,650 m/s (588,000 cu ft/s) for the Ganges, about 19,820 m/s (700,000 cu ft/s) for the Brahmaputra, and about 5,100 m/s (180,000 cu ft/s) for the Meghna.

The maximum peak discharge of the Ganges, as recorded at Hardinge Bridge in Bangladesh, exceeded 70,000 m/s (2,500,000 cu ft/s). The minimum recorded at the same place was about 650 m/s (23,000 cu ft/s), in 1976.

History

During the early Vedic Age, the Indus and the Sarasvati River were the major rivers of the Indian subcontinent, not the Ganges. But the later three Vedas seem to give much more importance to the Ganges, as shown by its numerous references.

The first European Traveler to mention the Ganges was Megasthenes (ca. 350 – 290 BCE).He did so several times in his work Indica: "India, again, possesses many rivers both large and navigable, which, having their sources in the mountains which stretch along the northern frontier, traverse the level country, and not a few of these, after uniting with each other, fall into the river called the Ganges. Now this river, which at its source is 30 stadia broad, flows from north to south, and empties its waters into the ocean forming the eastern boundary of the Gangaridai, a nation which possesses a vast force of the largest-sized elephants." (Diodorus II.37)

In Rome's Piazza Navona, a famous sculpture, Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (fountain of the four rivers) designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini was built in 1651. It symbolizes four of the world's great rivers (the Ganges, the Nile, the Danube, and the Río de la Plata), representing the four continents; Asia, Africa, Europe and America, thus the universality of the Catholic church, and its centre at Rome. The river is symbolised by a paddle to indicate its navigability.

Religious and cultural significance

Main article: Ganges in Hinduism

To Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, the Ganga symbolized the history, tradition and culture of India.He wrote in his will

The Ganga, especially is the river of India, beloved of her people, round which are intertwined her racial memories, her hopes and fears, her songs of triumph, her victories and her defeat. She has been a symbol of India's age-long culture and civilization, ever-changing, ever-flowing, and yet ever the same Ganga...

Many Hindus believe life is incomplete without taking a bath in the Ganges at least once in their lives. Many Hindu families keep a vial of water from the Ganges in their house. This is done because it is auspicious to have water of the Holy Ganges in the house, and also so that if someone is dying, that person will be able to drink its water. Many Hindus believe that the water from the Ganges can cleanse a person's soul of all past sins, and that it can also cure the ill.

According to Hindu religion, a very famous king Bhagiratha did Tapasya for many years constantly to bring the River Ganges, then residing in the Heavens, down on the Earth to find salvation for his ancestors, who were cursed by a seer. Therefore, the Ganges descended to the Earth through the mat of hair of god Shiva to make whole earth pious, fertile and wash out the sins of humans.

Dams and barrages

A major barrage at Farakka was opened on 21 April 1975, It is located close to the point where the main flow of the river enters Bangladesh, and the tributary Hooghly (also known as Bhagirathi ) continues in West Bengal past Calcutta. This barrage, which feeds the Hooghly branch of the river by a 26-mile (42 km) long feeder canal, and its water flow management has been a long-lingering source of dispute with Bangladesh. Indo-Bangladesh Ganges Water Treaty signed in December 1996 addressed some of the water sharing issues between India and Bangladesh.

Tehri Dam was constructed on Bhagirathi River, tributary of the Ganges. It's located 1.5 km downstream of Ganesh Prayag, the place where Bhilangana meets Bhagirathi. Bhagirathi is called Ganges after Devprayag. Construction of the dam in an earthquake prone area was controversial.

Irrigation

The first British canal in India—with no Indian antecedents—was the Ganges Canal built between 1842 and 1854. Contemplated first by Col. John Russell Colvin in 1836, it did not at first elicit much enthusiasm from its eventual architect Sir Proby Thomas Cautley, who balked at idea of cutting a canal through extensive low-lying land in order to reach the drier upland destination. However, after the Agra famine of 1837–38, during which the East India Company's administration spent Rs. 2,300,000 on famine relief, the idea of a canal became more attractive to the Company's budget-conscious Court of Directors. In 1839, the Governor General of India, Lord Auckland, with the Court's assent, granted funds to Cautley for a full survey of the swath of land that underlay and fringed the projected course of the canal. The Court of Directors, moreover, considerably enlarged the scope of the projected canal, which, in consequence of the severity and geographical extent of the famine, they now deemed to be the entire Doab region.

The enthusiasm, however, proved to be short lived. Auckland's successor as Governor General, Lord Ellenborough, appeared less receptive to large-scale public works, and for the duration of his tenure, withheld major funds for the project. Only in 1844, when a new Governor-General, Lord Hardinge, was appointed, did official enthusiasm and funds return to the Ganges canal project. Although the intervening impasse had seemingly affected Cautely's health and required him to return to Britain in 1845 for recuperation, his European sojourn gave him an opportunity to study contemporary hydraulic works in the United Kingdom and Italy. By the time of his return to India even more supportive men were at the helm, both in the North-Western Provinces, with James Thomason as Lt. Governor, and in British India with Lord Dalhousie as Governor-General. Canal construction, under Cautley's supervision, now went into full swing. A 350-mile long canal, with another 300 miles of branch lines, eventually stretched between the headworks in Hardwar, splitting into two branches below Aligarh, and its two confluences with the Yamuna (Jumna in map) mainstem in Etawah and the Ganges in Kanpur (Cawnpore in map). The Ganges Canal, which required a total capital outlay of £2.15 million, was officially opened in 1854 by Lord Dalhousie. According to historian Ian Stone:

It was the largest canal ever attempted in the world, five times greater in its length than all the main irrigation lines of Lombardy and Egypt put together, and longer by a third than even the largest USA navigation canal, the Pennsylvania Canal.

Economy

The Ganges Basin with its fertile soil is instrumental to the agricultural economies of India and Bangladesh. The Ganges and its tributaries provide a perennial source of irrigation to a large area. Chief crops cultivated in the area include rice, sugarcane, lentils, oil seeds, potatoes, and wheat. Along the banks of the river, the presence of swamps and lakes provide a rich growing area for crops such as legumes, chillies, mustard, sesame, sugarcane, and jute. There are also many fishing opportunities to many along the river, though it remains highly polluted. Kanpur, largest leather producing city in the world is situated on the banks of this river.

Tourism is another related activity. Three towns holy to Hinduism– Haridwar, Allahabad, and Varanasi– attract thousands of pilgrims to its waters. Thousands of Hindu pilgrims arrive at these three towns to take a dip in the Ganges, which is believed to cleanse oneself of sins and help attain salvation. The rapids of the Ganges also are popular for river rafting, attracting hundreds of adventure seekers in the summer months.

Pollution and ecology

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Snowded (talk | contribs) 13 years ago. (Update timer) |

The Ganges suffers from extreme pollution levels, which affect the 400 million people who live close to the river. Sewage from many cities along the river's course, industrial waste and religious offerings wrapped in non-degradable plastics add large amounts of pollutants to the river as it flows through densely populated areas. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that many poorer people rely on the river on a daily basis for bathing, washing, and cooking.

Varanasi, a city of one million people that many pilgrims visit to take a "holy dip" in the Ganges, releases around 200 million litres of untreated human sewage into the river each day, leading to large concentrations of faecal coliform bacteria. According to official standards, water safe for bathing should not contain more than 500 faecal coliforms per 100ml, yet upstream of Varanasi's ghats the river water already contains 120 times as much, 60,000 faecal coliform bacteria per 100 ml. After passing through Varanasi, and receiving 32 streams of raw sewage from the city, the concentration of faecal coliforms in the river's waters rises from 60,000 to 1.5 million, with observed peak values of 100 million per 100 ml. Drinking and bathing in its waters therefore carries a high risk of infection.

Between 1985 and 2000, Rs. 1,000 crore (Rs. 10 billion, around US$ 226 miilion, or less than 4 cents per person per year) were spent on the Ganga Action Plan, an environmental initiative that was "the largest single attempt to clean up a polluted river anywhere in the world." The Ganga Action Plan has been described variously as a "failure," a "major failure, a "colossal failure," and a "widely recognized failure."

According to one study,

The Ganga Action Plan, which was taken on priority and with much enthusiasm, was delayed for two years. The expenditure was almost doubled. But the result was not very appreciable. Much expenditure was done over the political propaganda. The concerning governments and the related agencies were not very prompt to make it a success. The public of the areas was not taken into consideration. The releasing of urban and industrial wastes in the river was not controlled fully. The flowing of dirty water through drains and sewers were not adequately diverted. The continuing customs of burning dead bodies, throwing carcasses, washing of dirty clothes by washermen, and immersion of idols and cattle wallowing were not checked. Very little provision of public latrines was made and the open defecation of lakhs of people continued along the riverside. All these made the Action Plan a failure.

The failure of the Ganga Action Plan, has also been variously attributed to "environmental planning without proper understanding of the human–environment interactions," Indian "traditions and beliefs," "corruption and a lack of technical knowledge" and "lack of support from religious authorities."

In December 2009 the World Bank agreed to loan India US$ 1 billion over the next five years to help save the river. According to 2010 Planning Commission estimates, an investment of almost Rs. 7,000 crore (Rs. 70 billion, approximately US$ 1.5 billion) is needed to clean up the river.

In November 2008, the Ganges, alone among India's rivers, was declared a "National River", facilitating the formation of a Ganga River Basin Authority that would have greater powers to plan, implement and monitor measures aimed at protecting the river.

The river's long-held reputation as a purifying river appears to have some basis in science. Its waters have been found to have unusual antimicrobial properties, shortening the survival time of pathogens. The underlying mechanism is unknown; possible explanations include antimicrobial peptides and bacteriophages. Even so, the incidence of water-borne and enteric diseases – such as gastrointestinal disease, cholera, dysentery, hepatitis A and typhoid – among people who use the river's waters for bathing, washing dishes and brushing teeth is high, at an estimated 66% per year.

Water shortages

Along with ever-increasing pollution, water shortages are getting noticeably worse. Some sections of the river are already completely dry. Around Varanasi the river once had an average depth of 60 metres (200 ft), but in some places it is now only 10 metres (33 ft).

- "To cope with its chronic water shortages, India employs electric groundwater pumps, diesel-powered tankers and coal-fed power plants. If the country increasingly relies on these energy-intensive short-term fixes, the whole planet's climate will bear the consequences. India is under enormous pressure to develop its economic potential while also protecting its environment—something few, if any, countries have accomplished. What India does with its water will be a test of whether that combination is possible."

The effects of climate change on the river

The Tibetan Plateau contains the world's third-largest store of ice. Qin Dahe, the former head of the China Meteorological Administration, said that the recent fast pace of melting and warmer temperatures will be good for agriculture and tourism in the short term; but issued a strong warning:

"Temperatures are rising four times faster than elsewhere in China, and the Tibetan glaciers are retreating at a higher speed than in any other part of the world.... In the short term, this will cause lakes to expand and bring floods and mudflows. . . . In the long run, the glaciers are vital lifelines for Asian rivers, including the Indus and the Ganges. Once they vanish, water supplies in those regions will be in peril."

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its Fourth Report, stated that the Himalayan glaciers which feed the river, were at risk of melting by 2035. The IPCC has now withdrawn that prediction, as the original source admitted that it was speculative and the cited source was not a peer reviewed finding. In its statement, the IPCC stands by its general findings relating to the Himalayan glaciers being at risk from global warming (with consequent risks to water flow into the Gangetic basin).

Ganges river dolphin

The Ganges River Dolphin, which used to exist in large schools near to urban centres in both the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, is now seriously threatened by pollution and dam construction. Their numbers have now dwindled to a quarter of their numbers of fifteen years before, and they have become extinct in the Ganges's main tributaries. A recent survey by the World Wildlife Fund found only 3,000 left in the water catchment of both river systems.

See also

Notes

- The Ganga: water use in the Indian subcontinent, by Pranab Kumar Parua, p. 33

- http://www.zeenews.com/news587747.html

- Legends of Devi, by Sukumari Bhattacharji, Ramananda Bandyopadhyay, p. 54

- http://books.google.com/books?id=law3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA334&lpg=PA334&dq=patliputra+ganga+Maurya+capital&source=bl&ots=Wv2uHWbYbj&sig=d6xjgueBEtEG610yTObwt8q-qgM&hl=en&ei=W3WsTbu5E4uurAf7_oWoCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q&f=false An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology By A. Ghosh page 334

- http://books.google.com/books?id=law3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA334&lpg=PA334&dq=patliputra+ganga+Maurya+capital&source=bl&ots=Wv2uHWbYbj&sig=d6xjgueBEtEG610yTObwt8q-qgM&hl=en&ei=W3WsTbu5E4uurAf7_oWoCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=kannauj&f=false An encyclopaedia of Indian archaeology By A. Ghosh page 199

- ^ http://www.greendiary.com/entry/ganga-is-dying-at-kanpur/

- ^ "India and pollution: Up to their necks in it", The Economist, 27 July 2008.

- ^ Haberman, David L. (2006), River of love in an age of pollution:the Yamuna River of northern India, University of California Press. Pp. 277, ISBN 0520247906, page 160, Quote: "The Ganga Action Plan, commonly known as GAP, was launched dramatically in the holy city of Banares (Varanasi) on June 14, 1985, by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who promised, "We shall see that the waters of the Ganga become clean once again." The stated task was "to improve water quality, permit safe bathing all along the 2,525 kilometers from the Ganga's origin in the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, and make the water potable at important pilgrim and urban centres on its banks." The project was designed to tackle pollution from twenty-five cities and towns along its banks in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal by intercepting, diverting, and treating their effluents. With the GAP's Phase II, three important tributaries—Damodar, Gomati, and Yamuna—were added to the plan. Although some improvements have been made to the quality of the Ganges's water, many people claim that the GAP has been a major failure. The environmental lawyer M. C. Mehta, for example, filed public interest litigation against project, claiming "GAP has collapsed."

- ^ Gardner, Gary, "Engaging Religion in the Quest for a Sustainable World", in Bright, Chris; et al. (eds.), State of the World: 2003, W. W. Norton & Company. Pp. 256, pp. 152–176, ISBN 0393323862

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor-first=(help) Quote: "The Ganges, also known as the Ganga, is one of the world's major rivers, running for more than 2,500 kilometers from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal. It is also one of the most polluted, primarily from sewage, but also from animal carcasses, human corpses, and soap and other pollutants from bathers. Indeed, scientists measure fecal coliform levels at thousands of times what is permissable and levels of oxygen in the water are similarly unhealthy. Renewal efforts have centered primarily on the government-sponsored Ganga Action Plan (GAP), started in 1985 with the goal of cleaning up the river by 1993. Several western-style sewage treatment plants were built along the river, but they were poorly designed, poorly maintained and prone to shut down during the region's frequent power outages. The GAP has been a colossal failure, and many argue that the river is more polluted now than it was in 1985. (page 166)" - ^ "Clean Up Or Perish", The Times of India, Mar 19, 2010

- ^ Sheth, Jagadish N. (2008), Chindia Rising, Tata McGraw-Hill Education. Pp. 205, ISBN 0070657084 Quote: "But the Indian government, as a whole, appears typically ineffective. Its ability to address itself to a national problem like environmental degradation is typified by the 20-year, $100 million Ganga Action Plan, whose purpose was to clean up the Ganges River. Leading Indian environmentalists call the plan a complete failure, due to the same problems that have always beset the government: poor planning, corruption, and a lack of technical knowledge. The river, they say, is more polluted than ever. (pages 67–68)"

- ^ Singh, Munendra; Singh, Amit K. (2007), "Bibliography of Environmental Studies in Natural Characteristics and Anthropogenic Influences on the Ganga River", Environ Monit Assess, 129: 421–432Quote: "In February 1985, the Ministry of Environment and Forest, Government of India launched the Ganga Action Plan, an environmental project to improve the river water quality. It was the largest single attempt to clean up a polluted river anywhere in the world and has not achieved any success in terms of preventing pollution load and improvement in water quality of the river. Failure of the Ganga Action Plan may be directly linked with the environmental planning without proper understanding of the human–environment interactions. The bibliography of selected environmental research studies on the Ganga River is, therefore, an essentially first step for preserving and maintaining the Ganga River ecosystem in future."

- ^ Tiwari, R. C. (2008), "Environmental Scenario in India", in Dutt, Ashok K.; et al. (eds.), Explorations in Applied Geography, PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. Pp. 524, ISBN 8120333845

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor-first=(help) Quote: "Many social traditions and customs are not only helping in environmental degradation but are causing obstruction to environmental management and planning. The failure of the Ganga Action Plan to clean the sacred river is partly associated to our traditions and beliefs. The disposal of dead bodies, the immersion of idols and public bathing are the part of Hindu customs and rituals which are based on the notion that the sacred river leads to the path of salvation and under no circumstances its water can become impure. Burning of dead bodies through wood, bursting of crackers during Diwali, putting thousands of tones of fule wood under fire during Holi, immersion of Durga and Ganesh idols into rivers and seas etc. are part of Hindu customs and are detrimental to the environment. These and many other rituals need rethinking and modification in the light of contemporary situations. (page 92)" - ^ Puttick, Elizabeth (2008), "Mother Ganges, India's Sacred River", in Emoto, Masaru (ed.), The Healing Power of Water, pp. 241–252, ISBN 1401908772

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) Quote: "There have been various projects to clean up the Ganges and other rivers, led by the Indian government's Ganga Action Plan launched in 1985 by Rajiv Gandhi, grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru. Its relative failure has been blamed on mismanagement, corruption, and technological mistakes, but also on lack of support from religios authorities. This may well be partly because the Brahmin priests are so invested in the idea of the Ganga's purity and afraid that any admission of its pollution will undermine the central role of the water in ritual, as well as their own authority. There are many temples along the river, conducting a brisk trade in ceremonies, including funerals, and sometimes also the sale of bottled Ganga jal. The more traditional Hindu priests still believe that blessing Ganga jal purifies it, although they are now a very small minority in vew of the scale of the problem. (page 248)" - "Ganges River". Encyclopædia Britannica (Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition ed.). 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Penn, James R. (2001). Rivers of the world: a social, geographical, and environmental sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 88. ISBN 9781576070420. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Gupta, Avijit (2007). Large rivers: geomorphology and management. John Wiley and Sons. p. 347. ISBN 9780470849873. Retrieved 23 April 2011. Cite error: The named reference "Gupta2007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Merriam-Webster (1997). Merriam-Webster's geographical dictionary. Merriam-Webster. p. 412. ISBN 9780877795469. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Sharad K. Jain; Pushpendra K. Agarwal; Vijay P. Singh (5 March 2007). Hydrology and water resources of India. Springer. pp. 334–342. ISBN 9781402051791. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ L. Berga (25 May 2006). Dams and Reservoirs, Societies and Environment in the 21st Century: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Dams in the Societies of the 21st Century, 22nd International Congress on Large Dams (ICOLD), Barcelona, Spain, 18 June 2006. Taylor & Francis. p. 1304. ISBN 9780415404235. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Dwarika Nath Dhungel; Santa B. Pun (2009). The Nepal-India Water Relationship: Challenges. Springer. p. 210. ISBN 9781402084027. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Pranab Kumar Parua (3 January 2010). The Ganga: water use in the Indian subcontinent. Springer. pp. 267–272. ISBN 9789048131020. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- M. Monirul Qader Mirza; Ema. Manirula Kādera Mirjā (2004). The Ganges water diversion: environmental effects and implications. Springer. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781402024795. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- Suvedī, Sūryaprasāda (2005). International watercourses law for the 21st century: the case of the river Ganges basin. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 61. ISBN 9780754645276. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Elhance, Arun P. (1999). Hydropolitics in the Third World: conflict and cooperation in international river basins. US Institute of Peace Press. pp. 156–158. ISBN 9781878379917. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Guy Arnold (1 May 2000). World strategic highways. Taylor & Francis. p. 223. ISBN 9781579580988. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- C. R. Krishna Murti; Gaṅgā Pariyojanā Nideśālaya; India. Environment Research Committee (1991). The Ganga, a scientific study. Northern Book Centre. p. 10. ISBN 9788172110215. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Romila Thapar (October 1971). "The Image of the Barbarian in Early India". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 13 (4): 415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - W. W. Tarn (1923). "Alexander and the Ganges". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 43 (2): 93–101.

- Stefano, Paolo Di (4 April 2011). "Io ricordo, memorie d'autore Lizzani: «Uso il cinema per conoscermi» «Incontrai Edith e Rossellini mi chiese: quando vi sposate? Stiamo insieme da 60 anni»". Corriere della Sera.it. Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 29 (help) - Stefano, Paolo Di. "Gian Lorenzo Bernini, piazza Navona, Fontana dei quattro fiumi, il Gange". www.gliscritti.it/. Gli Scritti Centro Culturale. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- Ghose, Sankar (1993). Jawaharlal Nehru, a biography. New Delhi: Allied Publishers Limited. p. 342. ISBN 81-7023-369-0. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Stefanovic, Karl (7 May 2010). "Taking the Plunge". 60 Minutes. Nine Network. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "''Mahabharata'', Book 3, Sections 107–109". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Stephen Brichieri-Colombi and Robert W. Bradnock (March 2003). "Geopolitics, Water and Development in South Asia: Cooperative Development in the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta". The Geographical Journal. 169 (1): 43–64.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - M. Rafiqul Islam (1987). "The Ganges Water Dispute: An Appraisal of a Third Party Settlement". Asian Survey. 27 (8): 918–934.

- Ramesh C. Sharma, Manju Bahuguna and Punam Chauhan (2008). "Periphytonic diversity in Bhagirathi:Preimpoundment study of Tehri dam reservoir" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering. 50 (4): 255–262.

- James N. Brune (15 February 1993). "The seismic hazard at Tehri dam". Tectonophysics. 218 (1-3): 281–286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Fred Pearce and Rob Butler (26 Januray 1991). "The dam that should not be built". NewScientist.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Stone 2002, p. 16

- "June 2003 Newsletter". Clean Ganga. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- Salemme, Elisabeth (22 January 2007). "The World's Dirty Rivers". Time. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Abraham, Wolf-Rainer. "Review Article. Megacities as Sources for Pathogenic Bacteria in Rivers and Their Fate Downstream". International Journal of Microbiology. 2011. doi:10.1155/2011/798292.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Ganga can bear no more abuse". Times of India. 18 July 2009.

- ^ Mandal, R. B. (2006), Water Resource Management, Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 9788180693182

- Caso, Frank; Wolf, Aaron T. (2010), Freshwater Supply Global Issues, Infobase Publishing. Pp. 350, ISBN 0816078262

{{citation}}: line feed character in|title=at position 18 (help). Quote: "Chronology: 1985 *India launches Phase I of the Ganga Action Plan to restore the Ganges River; most deem it a failure by the early 1990s.(page 320)." - Dudgeon, David (2005), "River Rehabilitation for Conservation of Fish Biodiversity in Monsoonal Asia", Ecology and Society, 10 (2): 15 Quote: "To reduce the water pollution in one of Asia's major rivers, the Indian Government initiated the Ganga Action Plan in 1985. The objective of this centrally funded scheme was to treat the effluent from all the major towns along the Ganges and reduce pollution in the river by at least 75%. The Ganga Action Plan built upon the existing, but weakly enforced, 1974 Water Prevention and Control Act. A government audit of the Ganga Action Plan in 2000 reported limited success in meeting effluent targets. Development plans for sewage treatment facilities were submitted by only 73% of the cities along the Ganges, and only 54% of these were judged acceptable by the authorities. Not all the cities reported how much effluent was being treated, and many continued to discharge raw sewage into the river. Test audits of installed capacity indicated poor performance, and there were long delays in constructing planned treatment facilities. After 15 yr. of implementation, the audit estimated that the Ganga Action Plan had achieved only 14% of the anticipated sewage treatment capacity. The environmental impact of this failure has been exacerbated by the removal of large quantities of irrigation water from the Ganges which offset any gains from effluent reductions."

- Bharati, Radha Kant (2006), Interlinking of Indian rivers, Lotus Press. Pp. 129, ISBN 8183820417Quote: "The World Bank estimates the health costs of water pollution in India to be equivalent to three per cent of the country's gross domestic product. With Indian rivers being severely polluted, interlinking them may actually increase these costs. Also, with the widely recognized failure of the Ganga Action Plan, there is a danger that contaminants from the Ganga basin might enter other basins and destroy their natural cleansing processes. The new areas that will be river-fed after the introduction of the scheme may experience crop failures or routing dur to alien compounds carried into their streams from the polluted Ganga basin streams. (page 26)"

- "World Bank loans India $1bn for Ganges river clean up". BBC News. 3 December 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "Ganga gets a tag: national river – Vote whiff in step to give special status", The Telegraph, November 5, 2008

- Self-purification effect of bacteriophage, oxygen retention mystery: Mystery Factor Gives Ganges a Clean Reputation by Julian Crandall Hollick. National Public Radio.

- "How India's Success is Killing its Holy River." Jyoti Thottam. Time Magazine. 19 July 2010, pp. 12–17.

- "How India's Success is Killing its Holy River." Jyoti Thottam. Time Magazine. 19 July 2010, p. 15.

- (AFP) – 17 Aug 2009 (17 August 2009). "Global warming benefits to Tibet: Chinese official. Reported 18/Aug/2009". Google.com. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "See s. 10.6 of the WGII part of the report at" (PDF). Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- The IPCC report is based on a non-peer reviewed work by the World Wildlife Federation. They, in turn, drew their information from an interview conducted by New Scientist with Dr. Hasnain, an Indian glaciologist, who admitted that the view was speculative. See: and On the IPCC statement withdrawing the finding, see:

- Puttick, Elizabeth (2008), "Mother Ganges, India's Sacred River", in Emoto, Masaru (ed.), The Healing Power of Water, pp. 241–252, ISBN 1401908772

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) Quote: "Wildlife is also under threat, particularly the river dolphins. They were one of the world's first protected species, given special status under the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BC. They're now a critically endangered species, although protected once again by the Indian government (and internationally under the CITES convention). Their numbers have shrunk by 75 per cent over the last 15 years, and they have become extinct in the main tributaries, mainly because of pollution and habitat degradation."

References

- Alley, Kelly D. (2002). On the Banks of the Ganga: When Wastewater Meets a Sacred River. University of Michigan press. ISBN 0-472-06808-3.

- Alter, Stephen (2001). Sacred Waters: A Pilgrimage up the Ganges River to the Source of Hindu Culture. . Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-100585-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Darian, Steven G (1978). The Ganges in Myth and History. The University Press of Hawaii, Honolulu. ISBN 0-8248-0509-7.

- Newby, Eric (1966). Slowly down the Ganges. ISBN 0-86442-631-3.

- Hillary, Edmund (1980). From the Ocean to the Sky: Jet Boating Up the Ganges. Ulverscroft Large Print Books Ltd. ISBN 0-7089-0587-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK (2004). "Cholera". Lancet. 363 (9404): 223–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15328-7. PMID 14738797.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Singh, Vijay (1994). The River Goddess. Moonlight Publishing, London.

- Stone, Ian (2002), Canal Irrigation in British India: Perspectives on Technological Change in a Peasant Economy (Cambridge South Asian Studies), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 392, ISBN 0521526639

Further reading

- Berwick, Dennison (1987). A walk along the Ganges. Dennison Berwick. ISBN 9780713719680. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Cautley, Proby Thomas (1864). Ganges canal. A disquisition on the heads of the Ganges of Jumna canals, North-western Provinces. London, Printed for Private circulation.

- Fraser, James Baillie (1820). Journal of a tour through part of the snowy range of the Himala Mountains, and to the sources of the rivers Jumna and Ganges. Rodwell and Martin, London.

- Hamilton, Francis (1822). An account of the fishes found in the river Ganges and its branches. A. Constable and company, Edinburgh.

External links

- ON THINNER ICE 如履薄冰: signs of trouble from the Water Tower of Asia, where headwaters feed into all the great rivers of Asia (by GRIP, Asia Society and MediaStorm)

- Ganges in the Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909

- Melting Glaciers Threaten Ganges

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law. Peace Palace Library

- Ganges as the River of India

- Ganga Ma: A Pilgrimage to the Source a documentary that follows the Ganges from the mouth to its source in the Himalayas.

- An article about the land and the people of the Ganges

| Hydrography of the Indian subcontinent | |

|---|---|

| Inland rivers | |

| Inland lakes, deltas, etc. | |

| Coastal | |

| Categories |

|

| Hydrography of Uttarakhand | |

|---|---|

| Rivers | |

| Lakes | |

| Glaciers | |

| Waterfalls | |

| Dams | |

| Barrages | |

| Bridges | |

| Related topics | |

| Hydrography of Uttar Pradesh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivers |

| ||||||

| Lakes | |||||||

| Dams and barrages | |||||||

| Canals | |||||||

| Bridges | |||||||

| Related topics | |||||||

| Hydrography of Bihar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivers |

| ||||

| Waterfalls | |||||

| Dams, barrages | |||||

| Bridges | |||||

| Related topics | |||||

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA

Categories:- Misplaced Pages neutral point of view disputes from April 2011

- Use dmy dates from February 2011

- Rivers of India

- National symbols of India

- Rivers of Uttarakhand

- Rivers of Uttar Pradesh

- Rivers of Bangladesh

- International rivers of Asia

- Sacred rivers

- Rigvedic rivers

- Geography of Uttar Pradesh

- Geography of Uttarakhand

- Ganges

- Ganges basin

- Bangladesh–India border