| Revision as of 08:22, 17 November 2010 editEsperfulmo (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users19,274 editsm {{lang|km← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:09, 3 February 2011 edit undoΔ (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers35,263 edits CleanupNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| '''Khmer classical dance''' ({{lang|km|រាំក្បាច់ខ្មែរ}}) is a form of dance from ] which shares some similarities with the classical dances of ] and ]. | '''Khmer classical dance''' ({{lang|km|រាំក្បាច់ខ្មែរ}}) is a form of dance from ] which shares some similarities with the classical dances of ] and ]. | ||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

| File:Khmerr restaurant dancer.jpg|A dancer in Robam Tep Monorom at a restaurant in Siem Reap. | File:Khmerr restaurant dancer.jpg|A dancer in Robam Tep Monorom at a restaurant in Siem Reap. | ||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| ⚫ | == Notes == | ||

| ⚫ | {{reflist|2}} | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 107: | Line 104: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | == Notes == | ||

| ⚫ | {{reflist|2}} | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 19:09, 3 February 2011

This file may be deleted after Thursday, February 10, 2011.

Khmer classical dance (រាំក្បាច់ខ្មែរ) is a form of dance from Cambodia which shares some similarities with the classical dances of Thailand and Laos.

The Cambodian form is known by various names in English, such as Khmer Royal Ballet and Cambodian Court Dance. In The Cambridge Guide to Theatre and in UNESCO's Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity list, it is referred to as the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, although UNESCO also uses the term "Khmer classical dance." In Khmer, it is formally known as robam preah reachea trop, which means 'dances of royal wealth' or simply robam. During the Lon Nol regime of Cambodia, its name was changed to robam kbach boran khmer, literally meaning 'Khmer dance of the ancient style', a term which does not make any reference to its royal past. Being a highly stylized art form performed primarily by females, Khmer classical dance, during the French protectorate era, was largely confined to the courts of royal palaces, performed by the consorts, concubines, relatives, and attendants of the palace; thus, Western names for the art often make reference to the royal court.

The dance form is also showcased in several forms of Khmer theatre (lkhaon) such as Lkhaon Kbach Boran (the main genre of classical dance drama performed by women) and Lkhaon Khaol (a genre of dance drama performed by men). Khmer classical dancers are often referred to as apsara dancers, which in the modern sense would be incorrect as the apsara is only a type of character performed by the dancers.

History

Cambodians scholars, such as Pech Tum Kravel, and French archaeologist George Groslier have mentioned that Khmer classical dance is part of an unbroken tradition dating to the Angkor period. Other scholars theorize that Khmer classical dance, as seen today, developed from, or was at least highly influenced by, Thai classical dance innovations from the 19th century and precedent forms were somewhat different.

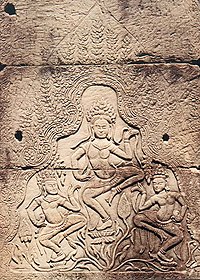

One of the earliest records of dance in Cambodia is from the 7th century, where performances were used as a funeral rite for kings and this ritual continues to this day. During the Angkor period, dance was ritually performed at temples. The temple dancers came to be considered as apsaras, who served as entertainers and messengers to divinities. Ancient stone inscriptions, describe thousands of apsara dancers assigned to temples and performing divine rites as well as for the public. The tradition of temple dancers declined during the 15th century, as the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya raided Angkor. When Angkor collapsed, its artisans, Brahmins, and dancers were taken to Ayutthaya. The tradition of royal court dance however, did continue.

In the 19th century, King Ang Duong, who had spent many years at the Siamese court in Bangkok, restructured his royal court with Siamese innovations. This restructuring also affected the classical dance of the royal court (a symbol of the king's wealth and power) whose costumes were remodelled after Thai classical dance costumes.

In the early 20th, dancers of the court of King Sisowath (second son of King Ang Duong to reign) were exhibited at the French Colonial Exposition in Marseilles where they captured the heart of French artist Auguste Rodin who painted many watercolors of the dancers. Many writers had compared classical dancers to the bas-relief of apsarases which may have led to the strong affinity many people have for the two today. After World War II, Khmer classical dance underwent a renaissance brought on by former Queen of Cambodia, Kossamak Nearireath, the mother of then Prince Sihanouk.

Khmer classical dance suffered a huge blow during the Khmer Rouge regime during which many dancers were killed because classical dance was thought as of an aristocratic institution. Although 90 percent of all Cambodian classical artists perished between 1975 and 1979 after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, those who did survive wandered out from hiding, found one another, and formed "colonies" in order to revive their sacred traditions. Khmer classical dance training was resurrected in the refugee camps in eastern Thailand with the few surviving Khmer dancers. Many dances and dance dramas were also recreated at the Royal University of Fine-Arts in Cambodia. The Royal Ballet of Cambodia was the main troupe of classical dancers in Cambodia before the Khmer Rouge regime, but since Cambodia has gain its peace, a few other professional and amateur troupes have risen.

Movement and gestures

Khmer classical dancers use stylized movements and gestures to tell a story much like a mime. Many people consider its style vague or abstract. Dancers do not speak or sing; they dance with a slight smile and are never supposed to open their mouths (though a few dramas have brief speaking parts). Khmer classical dance can be compared to French ballet in that it requires years of practice and stretching at a young age so the limbs become very flexible.

Hand gestures in Khmer classical dance are called kbach (meaning style). These hand gestures form a sort of alphabet and represent various things from nature such as fruit, flowers, and leaves. They are used in different combinations, sometimes with accompanying foot movements, to convey different thoughts and concepts. The way in which they are presented, the position of the arm, and the position of the hand relative to the arm can also affect their meaning. Besides hand gestures are gestures which are more specific to their meaning, such as that which is used to represent laughing or flying. These other gestures are performed in different manners depending on which type of character is played.

Characters and costume

Four main types of roles exist in Khmer classical dance; néay rông (men), néang (maidens), yéak (ogres or yaksha), and the sva (monkeys). These four basic roles contain sub-classes to indicate rank; a néay rông êk, for example, would be a leading male role and a néang philiĕng would be a maiden-servant. Other types of roles include mermaids, hermits, deer, garudas, and kinnaris. Most of these characters are still performed by female dancers, but a few such as monkey characters are almost exclusively performed by men because this role requires acrobatic stunts such as cartwheels. Other roles performed by men include hermits and animals such as horses and mythical lions used to draw chariots.

Classical dance costumes are highly ornate and heavily embroidered, sometimes including sequins and even semi-precious gems. Various pieces of the costume (such as shirts) have to be sewn onto the dancers for a tight fit.

Female costume

The typical female, or néang consists of a sâmpót sarâbăp; it is a type of brocade woven with two contrasting silk threads along with a metallic thread (gold or silver in color). The sâmpót is wrapped around the lower body in a sarong-like fashion, then pleated into a band in the front and secured with a gold or brass belt. Part of the pleated brocade band hangs over the belt on the left side of the belt buckle, which is a clear distinction from Thai classical dance costumes where this pleated band is tucked into the belt, right of the belt buckle. Worn over the left shoulder is a shawl-like garment called a sbai (also known as the rôbăng khnâng, literally 'back cover'), it is the most decorative part of the costume, embroidered extensively with tiny beads and sequins; the usual embroidery pattern for the sbai these days is a diamond pattern, but in the past there were floral patterns too. Under the sbai is a silk undershirt or bodice called an av păk with only a short sleeve exposed on the left arm. Around the neck is an embroidered collar called a srâng kâr.

Jewelry of the female role includes a large filigree, square pendant of which is hung by the corner, various types of ankle and wrists bracelets and bangles, an armlet on the right arm, and body chains of various styles. These body chains, in ancient Cambodia, were worn over the left shoulder as a means of displaying wealth. In dance costumes, more amounts of body chains indicate a role of higher rank.

The female role, traditionally, wears a red rose inserted above the right ear and a phuŏng (a flower tassel made from Jasminum sambac and Michelia alba or Michelia champaca blossoms) on the left side of the crown. Although, in modern times, these three flowers (the rose, jasmine, and Michelia), due to convenience, are often replaced with other flowers or faux flowers. Apsara characters often wear Plumeria obtusa flowers tied along the back of their hair.

Male costume

Male characters wear costumes that are more intricate than the females, as it requires pieces, like sleeves, to be sewn together while being put on. They are dressed in a sâmpót sarâbăp, like their female counterpart, however it is worn differently. For the male, or néay rông, the sâmpót is worn in the châng kben style, where the front is pleated and pulled under, between the legs, then tucked in the back and the remaining length of the pleat is stitched to the sâmpót itself to form a draping 'fan' in the back. Knee-length pants are worn underneath displaying a wide, embroidered hem around the knees. For the top, they wear long sleeved shirts with rich embroidering, with a collar, or srâng kâr, around their neck. On the end of their shoulders are a sort of epaulette that is arching upwards like Indra's bow (known as inthanu). Another component of the male costumes are three richly embroidered cloths worn around the front waist, that look like tassets. The center piece is known as a robang muk while the two side pieces are known as a cheay kraeng, while for monkeys and yaksha characters, they wear another piece in the back called a robang kraoy.

Male characters also wear an x-like strap around the body called a sângvar, often it is made of gold-colored silk and sometimes it is made from chains of gold with square ornaments, in which case it is reserved for more important characters. The males also wear the same ankle and wrist jewelry as the female, but with the addition of an extra set of bangles on the wrist and no armlets. They also wear a kite-shaped ornament called a slœ̆k pô (named after the Bo tree leaf) which serves as center point for their sângvar. As opposed to the female character, the male character wears a rose over the left ear and a flower tassel hung on the right side of the crown. Both male and female characters were played by women.

Headdress

Dancers wear either one of several different types of crowns which denote the ranks of the character they are performing. Divinities and royal characters wear a tall single-spired crown, called a mokot. Human characters of lesser importance wear various types of headdresses resembling circlets, diadems and tiaras. Characters such as ogres and monkeys wear masks and crowns attached to their masks according to their rank.Thai culture is highly influenced by the khmer people ancient culture.

Music

The music used for Khmer classical dance is played by a pinpeat orchestra. This type of orchestra consists of several types of xylophones, drums, oboes, gongs, and other musical instruments. While the pinpeat orchestra is not playing, a chorus of several singers will sing out lyrics which describe the story of the dance. New pieces of music are rarely created for this traditional art form. Khmer classical dance uses a particular piece of music for a certain event, such as when a dancer enters a scene, performing certain actions, such as flying, or walking, and when leaving the stage. These musical pieces, ranging from about one minute to as much as ten minutes long are arranged to form a suite.

Musical pieces

- Sathukar

- Krao Nai

- Raev

- Smaeu

- Reay

- Lea

- Cheut Chhing

Repertoire

There has been, relatively, little creative innovation with Khmer dance except during the times of King Ang Duong and Queen Mother Kossmak Nearireath where the bulk of many dances still performed originate from. According to The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre from 1997 there were about 40 dances and 60 dance dramas. As of recent years, new dances and dance dramas have been created under the guidance of Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, although they are not part of the traditional royal repertoire and mainly have been performed in Western venues. She has help to create such dance dramas as Samritechak, an adaptation of Shakespeare's Othello. Her latest work is a piece called Pamina Devi, an adaptation of Mozart's The Magic Flute. Much of this new work has been praised by Western press but have met a few opposition with some Khmer dance teachers.

The apsara dance of today was 'recreated' by former queen Kossamak Nearireath, Norodom Sihanouk's mother. Its costume is based on the bas-relief of apsarases on temple ruins but much of it, including its music and gesture is not unique from other classical Khmer dances which probably do not date back to the Angkor period. Commonly performed at public events is Robam Jun Por, a dance where dancers scatter flower petals as a gesture of offering best wishes.

Dance Dramas

Dance dramas exist in two main forms today. The most important one in Cambodia is the female dance drama of the royal court form called lkhaon kbach boran which is analogous to lakhon nai of Thailand. The lesser form of dance drama in Cambodia, from outside of the palace, is called lkhaon khaol, being limited only to performances of the Ramayana and performed only by men. Lkhaon khaol is almost extinct in Cambodia, and unlike its counterpart from Thailand, the khon dance drama, it is rarely performed and not as popular.

The subject of many dance dramas, or more specifically, dramas from the lkhaon kbach boran genre, was usually a that of a male character who rescues a damsel in distress. One such example was Roeung Kraithong and Chealavorn the epic of a hero named Kraithong adapted from Thai lore. However, some dance dramas had prominent female roles such is in Roeung Preah Sothon-Neang Keo Manorea and Roeung Kakei, the former of which was based on the Jataka tale of Sudhana and Manohara. Dances by Sophiline Cheam Shapiro are different from traditional ones in that they contain more emphasis into social changes, abstraction, feelings, and emotion.

Select list of dramas

- Reamker (or Ramakerti) - the Khmer version of the Ramayana

- Preah Sothon-Neang Kev Monorea - a drama adapted from the Jataka story of Prince Sudhana and the kinnari Manohara

- Preah Thaong-Neang Neak - a story about a naga princess and brahmin

- Krai Thong - an eponymous drama about a man who slays a crocodile to rescue the daughter of a tycoon

- Eynao-Bosba (Ino-Pushpa) - an adaptation of Inou, also known as Panji

- Kakey - a drama based on the Kakati-Jataka

- Preah Chinavong

- Sopheak Leak (Shubhalakshana)

- Preah Samut

Dances

Some dances, such as Robam Moni Mekhala and Robam Sovann Maccha are excerpts from dance dramas called lkhaon (also known as dance dramas). Lkhaon are different from robam in that it is longer, sometimes lasting several hours, while robam are dances lasting about a dozen minutes or so.

Select list of dances

- Robam Tep Apsara - a dance about the apsara named Yaovamalya and her servants picking flowers for her in a garden

- Robam Tep Monorom - a dance about angels dancing in delight

- Robam Thvay Preah Por - a dance presented to the King of Cambodia

- Robam Phuong Neari - a dance concerning the beauty of flowers and maidens

- Robam Moni Mekhala - an excerpted dance about Manimekhala with Ream Eyso (Parashurama) in pursuit of taking away her crystal ball

- Robam Makar - a dance where Manimekhala, Vorachhun (Arjuna), and a group of angels dance in line using fans to represent the scales of the Makara

- Robam Sovann Maccha - an excerpted dance from the Reamker about Hanuman and Suvannamaccha, the golden mermaid.

Gallery

-

Lady dancer, Siem Reap, September 2005

Lady dancer, Siem Reap, September 2005

- An adaptation of the Thai story of Sangthong. An adaptation of the Thai story of Sangthong.

-

A dancer in Robam Tep Monorom at a restaurant in Siem Reap.

A dancer in Robam Tep Monorom at a restaurant in Siem Reap.

See also

Notes

- portal.unesco.org/en The Royal Ballet of Cambodia;

- ^ Fletcher 2001, p. 306

- Banham 1995, p. 154

- Hideo 2005

- ^ Bradon 1967, p. 20

- Becker 1998, p. 330

- jumpcut.com Cambodian Royal Court Dancing;. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- Alliance for California Traditional Arts Classical Cambodian Dance Sophiline Cheam Shapiro and Socheata Heng. Retrieved July 21, 2007. Archived 2007-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- @nifty:フォーラム@nifty:ワールドフォーラム

- Mekhala: Intro

- Popular Cambodian Folktales

References

- Banham, Martin (1995). The Cambridge Guide to Theater, Cambridge University Press

- Becker, Elizabeth (1998). When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution, PublicAffairs

- Bowers, Faubion. (1956). Theatre in the East, New York T. Nelson

- Brandon, James R. (1967). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press

- Cravath, Paul (2008). Earth in Flower - The Divine Mystery of the Cambodian Dance Drama, DatAsia Press

- Fletcher, Peter (2001). World Musics in Context: A Comprehensive Survey of the World's Major Musical Cultures, Oxford University

- Heywood, Denise (2009). Cambodian Dance Celebration of the Gods, River Books

- Hideo, Sasagawa (2005). Post/colonial Discourses on the Cambodian Court Dance, Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4, March 2005

External links

- Andrew Page Photo Gallery of Cambodian Dance in America

- Cambodian Dancers - Historical info and 169 original etchings from George Groslier's 1913 book Danseuses Cambodgiennes

- Cambodian American Heritage Association

- Cambodian Classical Dance | Comprehensive dance history website by Chamroeun Yin and Tom Kramer

- Charya Burt Cambodian Dance

- Earth in Flower - Photo gallery of 186 Cambodian dance photos arranged by chronology and topic

- Ken Kunthea (French)| Homepage of this classical Khmer dancer, singer and choreographer

- Illustrated history of Cambodian dance, with Rodin’s drawings and biographies of surviving dancers from the Pol Pot regime

- Khmer Arts Academy | Founded by Sophiline Cheam Shapiro

- Nginn-Karet Foundation Teaches Sacred Dance at Banteay Srey

- The Language of Khmer Classical Dance - The Cambodia Daily

- The Near Extinction of Cambodian Classical Dance

- UNESCO Proclamation of Masterpieces