| Revision as of 06:37, 25 May 2010 editAlexpope (talk | contribs)106 edits Provided citation for term "La Chingada" and death date 1551 established by Sir Hugh Thomas in "Conquest."← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:08, 25 May 2010 edit undoAlexpope (talk | contribs)106 edits Corrected erroneous term "Aztec Empire" and updated the information on the name of Marina/ La Malinche.Next edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

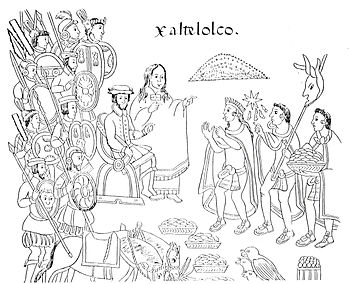

| ] in the city of Xaltelolco, in a drawing from the late 16th century ] ].]] | ] in the city of Xaltelolco, in a drawing from the late 16th century ] ].]] | ||

| '''La Malinche''' (c. 1496 or c. 1505 – c. 1529, some sources give 1550-1551), known also as '''Malintzin''', '''Malinalli''' or '''Doña Marina''', was a woman (almost certainly ]) from the Mexican ], who played as an active and powerful role in the ] conquest of ], acting as interpreter, advisor and intermediary for ]. She was one of twenty slaves given to Cortes by the natives of Tabasco in 1519 <ref> Thomas, Hugh. ''Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993, pp. 171-172 < |

'''La Malinche''' (c. 1496 or c. 1505 – c. 1529, some sources give 1550-1551), known also as '''Malintzin''', '''Malinalli''' or '''Doña Marina''', was a woman (almost certainly ]) from the Mexican ], who played as an active and powerful role in the ] conquest of ], acting as interpreter, advisor and intermediary for ]. She was one of twenty slaves given to Cortes by the natives of Tabasco in 1519 <ref> Thomas, Hugh. ''Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993, pp. 171-172 </ref> Later she became a ] to Cortés and gave birth to his first son, who is considered one of the first ] (people of mixed ] and ] ancestry). In Mexico today, La Malinche remains iconically potent. She is understood in various and often conflicting aspects, as the embodiment of treachery, the quintessential victim, or simply as symbolic mother of the new Mexican people. Historian Octavio Paz referred to her by the pejorative term '']'' .{{cited in Taylor, John, "Reinterpreting Malinche" }} The term ''malinchista'' refers to a disloyal Mexican. | ||

| ==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

| *{{es icon}} Maura, Juan Francisco. ''Españolas de ultramar''. Valencia: ], 2005. | *{{es icon}} Maura, Juan Francisco. ''Españolas de ultramar''. Valencia: ], 2005. | ||

| *''Traditions and Encounters - A Global Perspective on the Past'', by Bentley and Ziegler. | *''Traditions and Encounters - A Global Perspective on the Past'', by Bentley and Ziegler. | ||

| Thomas, Hugh. | |||

| Salas, Elizabeth. | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Malinche, La}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Malinche, La}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 08:08, 25 May 2010

For the volcano in Tlaxcala, see Matlalcueitl (volcano).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "La Malinche" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

La Malinche (c. 1496 or c. 1505 – c. 1529, some sources give 1550-1551), known also as Malintzin, Malinalli or Doña Marina, was a woman (almost certainly Nahuatl) from the Mexican Gulf Coast, who played as an active and powerful role in the Spanish conquest of Mexico, acting as interpreter, advisor and intermediary for Hernán Cortés. She was one of twenty slaves given to Cortes by the natives of Tabasco in 1519 Later she became a mistress to Cortés and gave birth to his first son, who is considered one of the first Mestizos (people of mixed European and indigenous American ancestry). In Mexico today, La Malinche remains iconically potent. She is understood in various and often conflicting aspects, as the embodiment of treachery, the quintessential victim, or simply as symbolic mother of the new Mexican people. Historian Octavio Paz referred to her by the pejorative term La Chingada .Template:Cited in Taylor, John, "Reinterpreting Malinche" The term malinchista refers to a disloyal Mexican.

Life

Origins

There is little certain information regarding Malinche's background. Most of what is reported about her early life comes through the reports of Cortés' "official" biographer (Francisco López de Gómara), and some of Cortés' contemporary conquistadores, such as Andrés de Tapia and (most importantly) Bernal Díaz del Castillo, whose vibrant chronicles Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España relate much of what is known.

According to Díaz, Malinche was the noble first-born child of the lord of Paynala (near present-day Coatzacoalcos, then a "frontier" region between the Aztec Empire and the Maya states of the Yucatán Peninsula). In her youth, her father died and her mother remarried and bore a son. Now an inconvenient stepchild, the girl was sold or given to Maya slave-traders from Xicalango, an important commercial town further south and east along the coast. Díaz claims Malinche's family faked her death by telling the townspeople that a recently deceased child of a slave was Malinche.

The Conquest of Mexico

Malinche was introduced to the Spanish in April 1519, when she was among twenty slave women given by the Chontal Maya of Potonchan (in the present-day state of Tabasco) to the triumphant Spaniards. Her age at the time is unknown, however assumptions have been made of her being in her twenties, as well as of the likelihood that she was striking in appearance according to European tastes of the time. It is suggestive of her appeal that Cortés singled her out as a gift for Alonzo Hernando Puertocarrero, perhaps the most well-born member of the expedition. Soon, however, Puertocarrero was on his way to Spain as Cortés' emissary to Charles V, and Cortés decided she was too valuable or attractive to be left in the care of anyone but himself.

According to the surviving indigenous and Spanish sources, within several weeks, the young woman had begun acting as interpreter - translating between the Nahuatl language (the then lingua franca of what is today central Mexico) and the Chontal Maya language. The Spanish priest Gerónimo de Aguilar understood the Mayan language, because he had spent several years in captivity among the Maya peoples in Yucatán following a shipwreck. Cortés used Malinche and Aguilar to interpret until La Malinche learned Spanish and could be used as the sole interpreter.

By the end of the year, when the Spaniards had installed themselves in the Mexican capital Tenochtitlan, it is apparent that the woman, now called "Malintzin" by native Mexicans, had learned enough Spanish to interpret directly between Cortés and the Aztecs. Native Mexicans, significantly, also call Cortés "Malintzin," an indication, perhaps, of how closely connected they had become.

According to surviving records, Malinche learned of several plans by natives to destroy the small Spanish army, and she alerted Cortés of the danger and even played along with the natives in order to lead them into traps.

Following the fall of Tenochtitlan in late 1521 and the birth of her son Don Martín Cortés in 1522, Malinche disappears from the record until Cortés' nearly disastrous Honduran expedition of 1524–26 when she is seen serving again as interpreter (suggestive of a knowledge of Maya dialects beyond Chontal and Yucatecan.) While in the forests of central Yucatán, she married Juan Jaramillo, a Spanish gentleman, with whom she had a daughter (also named Marina) around 1526 or 1527. Little or nothing more is known about her after this, even the year of her death, 1529, being somewhat in dispute. Some sources give the date 1551.

Role of La Malinche in the Conquest of Mexico

For the conquistadores, having a reliable translator was important enough, but there is evidence that Malinche's role and influence were larger still. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier who, as an old man, produced the most comprehensive of the eye-witness accounts, the Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España ("True Story of the Conquest of New Spain"), speaks repeatedly and reverentially of the "great lady" Doña Marina (always using the honorific, "Doña"). "Without the help of Doña Marina," he writes, "we would not have understood the language of New Spain and Mexico." Rodríguez de Ocana, another conquistador, relates Cortés' assertion that after God, Marina was the main reason for his success.

The evidence from indigenous sources is even more interesting, both in the commentaries about her role, and in her prominence in the drawings made of conquest events. In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (History of Tlaxcala), for example, not only is Cortés rarely portrayed without Malinche poised by his ear, but she is shown at times on her own, seemingly directing events as an independent authority. If she had been trained for court life, as in Díaz's account, her loyalty to Cortés may have been dictated by the familiar pattern of marriage among native elite classes. In the role of primary wife acquired through an alliance, her role would have been to assist her husband achieve his military and diplomatic objectives.

Origin of the name "La Malinche"

The many uncertainties which surround Malinche's role in the Spanish conquest begin with her name itself. Her birth name is not known. Before the twenty slave girls were distributed among the Spanish captains for their pleasure in "grinding corn", Cortés insisted that they be baptized, and it was here that the woman was given the Spanish name "Marina". We know that the Nahuas later call her "Malintzin". We do not know whether "Marina" was chosen because of a phonetic resemblance to her actual name, or chosen randomly from among common Spanish names of the time. "Malinche" is almost certainly a Spanish corruption of "Malintzin," which itself probably results from a Nahua mispronunciation of "Marina" plus the reverential "-tzin" suffix. A possible reading of her name as "Mãlin-tzin" can be translated as "Noble Prisoner/Captive" - a reasonable possibility, given her noble birth and her initial relationship to the Cortés expedition. This proposal suggests that the origin language of her name was Nahuatl, and that perhaps "Marina" was a Spanish approximation of "Mãlin-." Another possible origin, advocated by Díaz, is that "Malinche" referred to Cortés and not to Doña Marina, being a shortened form of "Marina's Captain" that was used by the Aztec when Marina served as Cortés' translator. There is a widely-held but unsubstantiated explanation for her name which starts with the Nahua word "Malinalli", a bad-luck daysign whose root meaning has something to do with a kind of grass (Nahua men—but less so women—were often named for their day-signs). If true, Mallinalli could be translated as "One Reed", a reference to the coming of Quetzalcoatl, the mythical Armageddon when Aztec civilization was supposed to end due to his divine wrath. The similarity between "Malinalli" and "Malintzin" has led to the notion that "Malinalli" might have been her original name; there is, however, nothing but the phonetic coincidence to support it.

The word malinchismo is used by some modern-day Mexicans to refer in a pejoratively way, to those countrymen who prefer a different way of life than the local one, or a life with other outside influences. Some historians believe that La Malinche saved her people: that without someone who was not only a fluent translator but who also advised both sides of the negotiations, the Spanish would have been far more violent and destructive in their conquest. The Aztec empire was destroyed, but the Aztec people, their language, and much of their history and culture weren't completely destroyed. It is argued, however, that without her help, Cortes would not have been successful in conquering the Aztecs as quickly, giving the Aztec people enough time to adapt to new technology and methods of warfare.

Malinche's figure in contemporary Mexico

Malinche's image has become a mythical archetype that Latin American artists have represented in various forms of art. Her figure permeates historical, cultural, and social dimensions of Latin American cultures. In modern times and in several genres, she is compared with the figure of the Virgin Mary, La Llorona (folklore story of the weeping woman) and with the Mexican soldaderas (women who fought beside men during the Mexican Revolution) for their brave actions.

Finally, one must understand that La Malinche's legacy is one of myth mixed with legend, and the opposing opinions of the Mexican people about the woman. Many see her as the founding figure of the Mexican nation. Most, however, see her as a traitor, as may be gathered from the profane nickname La Chingada.

In Modern Culture

| This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. |

La Malinche is the main protagonist in such works as the novel Feathered Serpent: A Novel of the Mexican Conquest by Colin Falconer, and The Golden Princess by Alexander Baron. In stark contrast, she is portrayed as a scheming, duplicitous traitor in Gary Jennings' novel Aztec. More recently she has been the focus in Malinche's Conquest by Ana Lanyon, a non-fiction account of the author's research into the historical and mythic woman who was Malinche. A novel published in 2006 by Laura Esquivel casts the Nahua, Malinalli, as one of history's pawns who becomes Malinche (the novel's title) a woman "trapped between the Mexican civilization and the invading Spaniards, and unveils a literary view of the legendary love affair". She appears as a true Christian and protector of her fellow native Mexicans in the novel Tlaloc weeps for Mexico by László Passuth.

La Malinche, in the name Marina ("for her Indian name is too long to be written"), also appears in the adventure novel Montezuma's Daughter, by H. Rider Haggard. First appearing in Chapter XIII, she saves the protagonist from torture and sacrifice.

A fictional journal written by La Malinche and discovered in an archeological dig is a central element in a 2008 adventure novel "The Treasure of La Malinche" by Jeffry S. Hepple.

In the fictional Star Trek universe, a starship, the USS Malinche was named for La Malinche. This was done by Hans Beimler, a native of Mexico City, who together with friend Robert Hewitt Wolfe later wrote a screenplay based on La Malinche called The Serpent and the Eagle. The screenplay was optioned by Ron Howard and Imagine Films and is currently under development at Paramount Pictures.

Octavio Paz addresses the issue of La Malinche's role as the mother of Mexican culture in The Labyrinth of Solitude. He uses her relation to Cortés symbolically to represent Mexican culture as originating from rape and violation. He uses the analogy that she essentially helped Cortés take over and destroy the Aztec state by submitting herself to him. His claim summarizes a major theme in the book, claiming that Mexican culture is a labyrinth.

In the animated television series The Mysterious Cities of Gold, which chronicles the adventures of a Spanish boy and his companions traveling throughout South America in 1532 to seek the lost city of El Dorado, a woman called "Marinche" becomes a dangerous adversary. The series was originally produced in Japan, and when translated into English, the name the Japanese had rendered as "Ma-ri-n-chi-e" was transliterated into "Marinche."

She was also referred to in the song Cortez the Killer by Neil Young.

See also

External links

- Hernando Cortes on the Web : Malinche / Doña Marina (resources)

- Pre-Columbian Women

- "Reinterpreting Malinche" by John Taylor, Ex Post Facto (2000)

- Leyenda y nacionalismo: alegorías de la derrota en La Malinche y Florinda "La Cava", Spanish-language article by Juan F. Maura comparing La Cava and Mexican Malinche.

References

- Thomas, Hugh. Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993, pp. 171-172

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest

- Díaz 1963, p. 150

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1963) . The Conquest of New Spain. J. M. Cohen (trans.). London: The Folio Society.

- Maura, Juan Francisco.Women in the Conquest of the Americas. Translated by John F. Deredita. New York: Peter Lang, 1997.

- Template:Es icon Maura, Juan Francisco. Españolas de ultramar. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia, 2005.

- Traditions and Encounters - A Global Perspective on the Past, by Bentley and Ziegler.

Thomas, Hugh. Salas, Elizabeth.

Categories: