| Revision as of 01:56, 14 May 2010 editDBaba (talk | contribs)16,294 editsm →Trophy taking← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:30, 14 May 2010 edit undoStor stark7 (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers4,163 edits undid one blanking of sourced infoNext edit → | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| == Trophy taking == | == Trophy taking == | ||

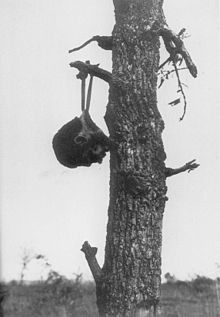

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| In addition to trophy skulls, teeth, ears and other such objects, taken body parts were occasionally modified, for example by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts.<ref name="Harrison826">{{cite journal | author=Simon Harrison | title=Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance | journal=Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute | pages=826 | volume=12 | year=2006 |url = http://www.science.ulster.ac.uk/psyri/profiles/s_harrison/documents/skulltrophies.pdf|format=PDF}}</ref> | In addition to trophy skulls, teeth, ears and other such objects, taken body parts were occasionally modified, for example by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts.<ref name="Harrison826">{{cite journal | author=Simon Harrison | title=Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance | journal=Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute | pages=826 | volume=12 | year=2006 |url = http://www.science.ulster.ac.uk/psyri/profiles/s_harrison/documents/skulltrophies.pdf|format=PDF}}</ref> "U.S. Marines on their way to ] relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and "pickling" Japanese ears as keepsakes."<ref>{{cite journal | author=James J. Weingartner | url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0030-8684(199202)61:1%3C53:TOWUTA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-O | title=Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945 | journal=] | pages=556 | volume=61 | issue=1 | month=February | year=1992}}</ref> In an air base in New Guinea hunting the last remaining Japanese was a “sort of hobby”. The leg-bones of these Japanese were sometimes carved into letter openers and pen-holders,<ref name="Harrison826" /> but this was rare.<ref name="Harrison827" /> | ||

| According to veteran Donald Fall "n ] a lot of guys who captured Japs tried to pry their mouths open to take the gold teeth out. They did that with dead ones too."<ref>Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations" p.186</ref> ] also relates a few instances of fellow Marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese, including one from a wounded Japanese. Since the Japanese was struggling the Marine tried to facilitate the extraction by slashing the victim's cheeks from ear to ear and kneeling on his chin. He was promptly shouted down by Sledge and others in Company K, and another Marine ran over and shot the wounded Japanese soldier. The Marine took his prize and drifted away, cursing the others for their humanity.<ref>('']''. p 120</ref> | According to veteran Donald Fall "n ] a lot of guys who captured Japs tried to pry their mouths open to take the gold teeth out. They did that with dead ones too."<ref>Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations" p.186</ref> ] also relates a few instances of fellow Marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese, including one from a wounded Japanese. Since the Japanese was struggling the Marine tried to facilitate the extraction by slashing the victim's cheeks from ear to ear and kneeling on his chin. He was promptly shouted down by Sledge and others in Company K, and another Marine ran over and shot the wounded Japanese soldier. The Marine took his prize and drifted away, cursing the others for their humanity.<ref>('']''. p 120</ref> | ||

Revision as of 10:30, 14 May 2010

| This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material that does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (May 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

During World War II, some United States military personnel mutilated dead Japanese service personnel in the Pacific theater of operations. The mutilation of Japanese service personnel included the taking of body parts as “war souvenirs” and “war trophies”. Teeth and skulls were the most commonly taken "trophies", although other body parts were also collected.

The phenomenon of "trophy-taking" was widespread enough that discussion of it featured prominently in magazines and newspapers, and Franklin Roosevelt himself was reportedly gifted a letter-opener made of a man's arm (Roosevelt rejected the gift and called for its proper burial). The behavior was officially prohibited by the U.S. military, which issued additional guidance as early as 1942 condemning it specifically. Nonetheless, the behavior continued throughout the war in the Pacific Theater, and has resulted in continued discoveries of "trophy skulls" of Japanese combatants in American possession, as well as American and Japanese efforts to repatriate the remains of the Japanese dead.

Trophy taking

In addition to trophy skulls, teeth, ears and other such objects, taken body parts were occasionally modified, for example by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts. "U.S. Marines on their way to Guadalcanal relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and "pickling" Japanese ears as keepsakes." In an air base in New Guinea hunting the last remaining Japanese was a “sort of hobby”. The leg-bones of these Japanese were sometimes carved into letter openers and pen-holders, but this was rare.

According to veteran Donald Fall "n New Britain a lot of guys who captured Japs tried to pry their mouths open to take the gold teeth out. They did that with dead ones too." Eugene Sledge also relates a few instances of fellow Marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese, including one from a wounded Japanese. Since the Japanese was struggling the Marine tried to facilitate the extraction by slashing the victim's cheeks from ear to ear and kneeling on his chin. He was promptly shouted down by Sledge and others in Company K, and another Marine ran over and shot the wounded Japanese soldier. The Marine took his prize and drifted away, cursing the others for their humanity.

Another example of mutilation was related by Marine Ore Marion to Bergerud, he related how hatred for the Japanese influenced his and his comrades behavior; "At daybreak, a couple of our kids, bearded, dirty, skinny from hunger, slightly wounded by bayonets, clothes worn and torn, wack off three Jap heads and jam them on poles facing the 'jap side' of the river."

In 1944 the American poet Winfield Townley Scott was working as a reporter in Rhode Island when a sailor displayed his skull trophy in the newspaper office. This led to the poem The U.S. sailor with the Japanese skull, which described one method for preparation of skulls (the head is skinned, towed in a net behind a ship to clean and polish it, and in the end scrubbed with caustic soda).

In October 1943, the U.S. High Command expressed alarm over recent newspaper articles, for example one where a soldier made a string of beads using Japanese teeth, and another about a soldier with pictures showing the steps in preparing a skull, involving cooking and scraping of the Japanese heads.

Charles Lindbergh refers in his diary to many instances of Japanese with an ear or nose cut off. In the case of the skulls however, most were not collected from freshly killed Japanese; most came from already partially or fully skeletonised Japanese bodies.

On February 1, 1943, Life magazine published a photograph taken by Ralph Morse during the Guadalcanal campaign showing a decapitated Japanese head that US marines had propped up below the gun turret of a tank. Life received letters of protest from people "in disbelief that American soldiers were capable of such brutality toward the enemy." The editors responded that "war is unpleasant, cruel, and inhuman. And it is more dangerous to forget this than to be shocked by reminders." However, the image of the decapitated head generated less than half the amount of protest letters that an image of a mistreated cat in the very same issue received.

Extent of practice

According to Weingartner it is not possible to determine the percentage of US troops that collected Japanese body parts, "but it is clear that the practice was not uncommon". According to Harrison only a minority of US troops collected Japanese body parts as trophies, but "their behaviour reflected attitudes which were very widely shared." According to Dower most U.S. combatants in the Pacific did not engage in "souvenir hunting" for bodyparts. The majority had some knowledge that these practices were occurring, however, and "accepted them as inevitable under the circumstances". The incidence of soldiers collecting Japanese body parts occurred on "a scale large enough to concern the Allied military authorities throughout the conflict and was widely reported and commented on in the American and Japanese wartime press". The degree of acceptance of the practice varied between units. Taking of teeth was generally accepted by enlisted men and also by officers, while acceptance for taking other body parts varied greatly. In the experience of one serviceman turned author, Weinstein, ownership of skulls and teeth were widespread practices.

When interviewed by researchers former servicemen have related to the practice of taking gold teeth from the dead - and sometimes also from the living - as having been widespread.

There is some disagreement between historians over what the more common forms of 'trophy hunting' undertaken by U.S. personnel were. John W. Dower states that ears were the most common form of trophy which was taken, and skulls and bones were less commonly collected. In particular he states that "skulls were not popular trophies" as they were difficult to carry and the process for removing the flesh was offensive. This view is supported by Simon Harrison. In contrast, Niall Ferguson states that "boiling the flesh off enemy skulls to make souvenirs was a not uncommon practice. Ears, bones and teeth were also collected".

The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the campaign, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking. Harrison concludes that since this was the first real opportunity to take such items (the battle of Guadalcanal), "Clearly, the collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered." When Charles Lindbergh passed through customs at Hawaii in 1944, one of the customs declarations he was asked to make was whether or not he was carrying any bones. He was told after expressing some shock at the question that it had become a routine point. This was because of the large number of souvenir bones discovered in customs, also including “green” (uncured) skulls.

In 1984 Japanese soldiers' remains were repatriated from the Mariana Islands. Roughly 60 percent were missing their skulls. Likewise it has been reported that many of the Japanese remains in Iwo Jima are missing their skulls. It is possible that the souvenir collection of remains continued also in the immediate post-war period.

Context

According to Simon Harrison, all of the "trophy skulls" from the WWII era in the forensic record in the U.S. attributable to an ethnicity are of Japanese origin; none come from Europe. (A seemingly rare exception to this rule was the case of a German soldier scalped by an American soldier, in accordance with Winnebago tribal custom.) Skulls from WWII, and also from the Vietnam War, continue turning up in the U.S., sometimes returned by former servicemen or their relatives, or discovered by police. According to Harrison, contrarily to the situation in average head-hunting societies the trophies do not fit in in American society. While the taking of the objects was socially accepted at the time, after the war, when the Japanese in time became seen as fully human again, the objects for the most part became seen as unacceptable and unsuitable for display. Therefore in time they and the practice that had generated them were largely forgotten.

Australian soldiers also mutilated Japanese bodies at times, most commonly by taking gold teeth from corpses. This was officially discouraged by the Australian Army. Johnson states that "one could argue that greed rather than hatred was the motive" for this behavior but "utter contempt for the enemy was also present". Australians are also known to have taken gold teeth also from German corpses, "but the practice was obviously more common in the South-West Pacific". "The vast majority of Australians clearly found such behaviour abhorrent, but" some of the soldiers who engaged in it were not 'hard cases'. According to Johnston Australian soldiers' "unusually murderous behavior" towards their Japanese opponents (such as killing prisoners) was caused by racism, a lack of understanding of Japanese military culture and, most significantly, a desire to take revenge against the murder and mutilation of Australian prisoners and native New Guineans during the Battle of Milne Bay and subsequent battles.

From the Burma Campaign there are recorded instances of British troops removing gold teeth and displaying Japanese skulls as trophies.

Motives

Dehumanization

In the U.S. there was a widely held view that the Japanese were subhuman. There was also popular anger in U.S. at the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor amplifying pre-war racial prejudices. The U.S. media helped propagate this view of the Japanese, for example describing them as “yellow vermin”.. In an official U.S. Navy film Japanese troops were described as “living, snarling rats”. The mixture of racism, propaganda, and real and imagined Japanese atrocities led to intense loathing of the Japanese. (see also Japanese war crimes) And although there were objections to the mutilation from amongst other military jurists, "to many Americans the Japanese adversary was no more than an animal, and abuse of his remains carried with it no moral stigma.

According to Niall Ferguson: "To the historian who has specialized in German history, this is one of the most troubling aspects of the Second World War: the fact that Allied troops often regarded the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians – as Untermenschen." Since the Japanese were regarded as animals it is not surprising that the Japanese remains were treated in the same way as animal remains.

Simon Harrison comes to the conclusion in his paper “Skull trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance” that the minority of U.S. personnel who collected Japanese skulls did so as they came from a society which placed much value in hunting as a symbol of masculinity, combined with a de-humanization of the enemy.

Brutalization

Some writers and veterans state that the body parts trophy and souvenir taking was a side effect of the brutalizing effects of a harsh campaign.

Harrison argues that while brutalization could explain part of the mutilations, this explanation does not explain the servicemen who already before shipping off for the Pacific proclaimed their intention to acquire such objects. According to Harrison it also does not explain the many cases of servicemen collecting the objects as gifts for people back home. Harrison concludes that there is no evidence that the average serviceman collecting this type of souvenirs was suffering from "combat fatigue". They were normal men who felt this was what their loved ones wanted them to collect for them. Skulls were sometimes also collected as souvenirs by non-combat personnel.

Revenge

Domestic American propaganda during World War II helped create antagonistic feelings in the US towards the Japanese. A 1944 opinion poll found that 13% of the U.S. public were in favor of the extermination of the entire Japanese population. But despite the impact of this propaganda, U.S. Army opinion surveys found that the high degree of hatred towards the Japanese expressed by soldiers in training typically declined dramatically once the men entered combat.

Bergerud writes that U.S. troops hostility towards their Japanese opponents largely arose from incidents in which Japanese soldiers committed war crimes against Americans, such as the Bataan Death March and other incidents conducted by individual soldiers. For instance, Bergerud states that the U.S. Marines on Guadacanal were aware that the Japanese had beheaded some of the marines captured on Wake Island prior to the start of the campaign. However this type of knowledge did not necessarily lead to revenge mutilations, one marine states that they falsely thought the Japanese had not taken any prisoners at Wake Island, and therefore as revenge they killed all Japanese that tried to surrender. (see also Allied_war_crimes_during_World_War_II)

The earliest account of U.S. troops wearing ears from Japanese corpses he recounts took according to one Marine place on the second day of the Guadalcanal Campaign in August 1942 and occurred after photos of the mutilated bodies of Marines on Wake Island were found in Japanese engineers' personal effects. The account of the same marine also states that Japanese troops booby trapped some of their own dead as well as some dead marines, and also mutilated corpses; the effect on marines being "We began to get down to their level". According to Bradley A. Thayer, refering to Bergerud and interviews conducted by Bergerud, the behaviors of American and Australian soldiers were affected by "intense fear, coupled with a powerful lust for revenge".

Weingartner writes however that U.S. Marines were intent on taking gold teeth and making keepsakes of Japanese ears already while en-route to Guadacanal.

Souvenirs and bartering

Factors relevant to the collection of body parts were their economic value, the desire both of the "folks back home" for a souvenir and of the servicemen themselves to keep a keepsake when they returned home.

Some of the collected souvenir bones were modified, e.g. turned into letter-openers, and may be an extension of trench art.

Pictures showing the "cooking and scraping" of Japanese heads may have formed part of the large set of Guadalcanal photographs sold to sailors which were circulating on the U.S. West-coast. According to Paul Fussel, pictures showing this type of activity, i.e. boiling human heads; "were taken (and preserved for a lifetime) because the marines were proud of their success".

In many cases (and unexplainable by battlefield conditions) the collected body parts were not for the use of the collector but were instead meant to be gifts to family and friends at home. In some cases as the result of specific requests from home. Newspapers reported of cases such as a mother requesting permission for her son to send her an ear, a bribed chaplain that was promised by an underage youth "the third pair of ears he collected". A better known example of those servicemen who left for battle already planning to send home a trophy is the Life Magazine picture of the week, whose caption begins:

- "When he said goodby two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends,..."

Another example of this type of press is Yank that in early 1943 published a cartoon showing the parents of a soldier receiving a pair of ears from their son. In 1942 Alan Lomax recorded a blues song where a black soldier promises to send his child a Japanese skull, and a tooth. Harrison also makes note of the Congressman that gave president Roosevelt a letter-opener carved out of bone as examples of the social range of these attitudes.

Trade sometimes occurred with the items, such as "members of the Naval Construction Battalions stationed on Guadalcanal selling Japanese skulls to merchant seamen" as reported in an Allied intelligence report from early 1944. Sometimes teeth (particularly the less common gold teeth) were also seen as a trade-able commodity.

U.S. reaction

“Stern disciplinary action” against human remains souvenir taking was ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet as early as September 1942. In October 1943 General George C. Marshall radioed General Douglas MacArthur about “his concern over current reports of atrocities committed by American soldiers”. In January 1944 the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive against the taking of Japanese body parts. Simon Harrison writes that directives of this type may have been effective in some areas, "but they seem to have been implemented only partially and unevenly by local commanders".

On May 22, 1944 Life Magazine published a photo of an American girl with a Japanese skull sent to her by her naval officer boyfriend. The letters Life received from its readers in response to this photo were "overwhelmingly condemnatory" and the Army directed its Bureau of Public Relations to inform U.S. publishers that “the publication of such stories would be likely to encourage the enemy to take reprisals against American dead and prisoners of war.” The junior officer who had sent the skull was also traced and officially reprimanded. This was done reluctantly however, and the punishment was not severe.

The Life photo also led to the U.S. Military to take further action against the mutilation of Japanese corpses. In a memorandum dated June 13, 1944, the Army JAG asserted that “such atrocious and brutal policies” in addition to being repugnant also were violations of the laws of war, and recommended the distribution to all commanders of a directive pointing out that “the maltreatment of enemy war dead was a blatant violation of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the sick and wounded, which provided that: After every engagement, the belligerent who remains in possession of the field shall take measures to search for wounded and the dead and to protect them from robbery and ill treatment.” Such practices were in addition also in violation of the unwritten customary rules of land warfare and could lead to the death penalty. The Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that “the atrocious conduct of which some U.S. servicemen were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law”.

On 13 June 1944 the press reported that President Roosevelt had been presented with a letter-opener made out of a Japanese soldier's arm bone by Francis E. Walter, a Democratic congressman. Several weeks later it was reported that it had been given back with the explanation that the President did not want this type of object and recommended it be buried instead. In doing so, Roosevelt was acting in response to the concerns which had been expressed by the military authorities and some of the civilian population, including church leaders.

In October 1944 the Right Rev. Henry St. George Tucker, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, issued a statement which deplored "'isolated' acts of desecration with respect to the bodies of slain Japanese soldiers and appealed to American soldiers as a group to discourage such actions on the part of individuals."

Japanese reaction

News that President Roosevelt had been given a bone letter opener by a congressman were widely reported in Japan. The Americans were portrayed as “deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman”. This reporting was compounded by the previous May 22, 1944 Life Magazine picture of the week publication of a young woman with a skull trophy. Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of mutilating the Japanese dead and taking pieces of them home was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings".

See also

References

- http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3651/is_199510/ai_n8714274/pg_1 Missing on the home front, National Forum, Fall 1995 by Roeder, George H Jr

- Lewis A. Erenberg, Susan E. Hirsch book: The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II. 1996. Page 52. ISBN 0226215113.

- ^ Harrison, p.825 Cite error: The named reference "Harrison822" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Simon Harrison (2006). "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 12: 826.

- James J. Weingartner (1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 556.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Harrison, p.827

- Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations" p.186

- (With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. p 120

- Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations" p.186

- "War, Journalism, and Propaganda"

- ^ Weingartner, p.56

- ^ Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy. Race and Power in the Pacific War. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571146058., p. 66

- Harrison, p.818

- Harrison p.822,823

- Film exposes Allies' Pacific war atrocities Horrific footage shot during battle with Japanese shows execution of wounded and bayoneting of corpses. Jason Burke The Observer, Sunday 3 June 2001

- Dower, p. 65

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2007). The War of the World. History's Age of Hatred. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141013824., p. 546

- Dower, John W. (1986). War Without Mercy. Race and Power in the Pacific War. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571146058., p. 71

- ^ Harrison, p.828

- "The taking and displaying of human body parts as trophies by Amerindians", Chacon and Dye, page 625

- ^ Johnston, Mark (2000). Fighting the Enemy. Australian Soldiers and their Adversaries in World War II. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521782228. p.82

- Johnston, pp. 81–100

- T. R. Moreman "The jungle, the Japanese and the British Commonwealth armies at war, 1941-45", p.205

- Weingartner, p.67

- ^ Weingartner, p.54

- Weingartner, p.54. Japanese were alternatively described and depicted as “mad dogs”, “yellow vermin”, termites, apes, monkeys, insects, reptiles and bats etc.

- Weingartenr p.66,67

- Ferguson, Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War, p. 182

- ^ Harrison, p.823

- ^ Harrison, p.824

- ^ Harrison, p.825

- Bagby 1999, p. 135 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBagby1999 (help)

- Public Opinion Polls on Japan, by Arthur N. Feraru.

- Spector, Ronald H. (1984). Eagle Against the Sun. The American War with Japan. London: Cassel & Co. ISBN 0304359793., p. 411

- Stanley Coleman Jersey "Hell's islands: the untold story of Guadalcanal", p. 169, 170

- Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations" p.186

- Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations" p.185

- James J. Weingartner (1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 556.

{{cite journal}}: Text ""U.S. Marines on their way to Guadalcanal relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and "pickling" Japanese ears" as keepsakes."" ignored (help) - Harrison p.826

- Weingartner p. 56,57

- Harrison p.822

- ^ Harrison p.824

- Weingartner p.56, 57

- Harrison p.825

- ^ Harrison p.823

- ^ Weingartner, p.57

- The image depicts a young blond at a desk gazing at a skull. The caption says “When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: "This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach." Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.

- Weingartner, p.58

- Weingartner, p.60

- Weingartner, p.65, 66

- ^ Weingartner, p.59

- "Tucker Deplores Desecration of Foe; Mutilation of Japanese Bodies Contrary to Spirit of Army, He Says of 'Isolated' Cases". The New York Times. 1944-10-14.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "The Morals of Victory". Time. 1944-10-23. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Harrison, p.833

Further reading

- Paul Fussell "Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War"

- Bourke "An Intimate History of Killing" (pages 37–43)

- Dower "War without mercy: race and power in the Pacific War" (pages 64–66)

- Fussel "Thank God for the Atom Bomb and other essays" (pages 45–52)

- Aldrich "The Faraway War: Personal diaries of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific"

- Hoyt "Japan's war: the great Pacific conflict"

- Charles A. Lindbergh (1970). The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

External links

- One War Is Enough War Correspondent EDGAR L. JONES 1946

- American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs'

- The US Sailor with the Japanese Skull by Winfield Townley Scott

- Eerie Souvenirs From the Vietnam War Washington Post July 3, 2007 By Michelle Boorstein]

- 2002 Virginia Festival of the Book: Trophy Skulls

- War against subhumans: comparisons between the German War against the Soviet Union and the American war against Japan, 1941-1945 The Historian 3/22/1996, Weingartner, James

- Racism in Japanese in U.S. wartime propaganda The Historian 6/22/1994 Brcak, Nancy; Pavia, John R.

- MACABRE MYSTERY Coroner tries to find origin of skull found during raid by deputies The Pueblo Chieftain Online.

- Skull from WWII casualty to be buried in grave for Japanese unknown soldiers Stars and Stripes

- HNET review of Peter Schrijvers. The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II.

- The May 1944 Life Magazine picture of the week (Image)