| Revision as of 14:18, 12 March 2010 view sourceHires an editor (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers4,687 edits Undid revision 349414929 by Jvol (talk) - undue weight to al qaeda and taliban, and E Europe wasn't 'freed' as such.← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:42, 14 March 2010 view source Communicat (talk | contribs)1,248 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

| Stalin was aware that the Americans were working on the atomic bomb and, given that the Soviets' own rival program was in place, he reacted to the news calmly. The Soviet leader said he was pleased by the news and expressed the hope that the weapon would be used against Japan.<ref name="Gaddis25">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=25–26}}</ref> One week after the end of the Potsdam Conference, the US ]. Shortly after the attacks, Stalin protested to US officials when Truman offered the Soviets little real influence in ].<ref>{{Harvnb|LaFeber|2002|p=28}}</ref> | Stalin was aware that the Americans were working on the atomic bomb and, given that the Soviets' own rival program was in place, he reacted to the news calmly. The Soviet leader said he was pleased by the news and expressed the hope that the weapon would be used against Japan.<ref name="Gaddis25">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=25–26}}</ref> One week after the end of the Potsdam Conference, the US ]. Shortly after the attacks, Stalin protested to US officials when Truman offered the Soviets little real influence in ].<ref>{{Harvnb|LaFeber|2002|p=28}}</ref> | ||

| ==Early blows in the political Cold War== | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ===Greece=== | |||

| ]In Greece the American intelligence community took virtual control of the country’s entire post-war social, political, military and economic structures. These were planned, decided and executed by the American Mission in Greece, including support for pro-Nazi Greeks who had hunted down partisans and participated in the mass murder of about 70,000 Greek Jews during the war. Greek civil liberties were eroded, the communist-led former partisan movement ELAS-EAM was all but destroyed, pro-monarchist armed forces were greatly strengthened, the trade union movement completely undermined, and a virulent anti-communist swing manipulated in Greek affairs as a whole. <ref> Lawrence S Wittner, ''American Intervention in Greece 1943-1949'', New York: Columbia, 1982; John O Iatrides (ed), ''Greece in the 1940s'', Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1981; Howard Jones, ''A New Kind of War: America's global strategy and the Truman Doctrine in Greece'', London: Oxford University Press 1989. Bruce R Kuniholm, ''Origins of the Cold War in the Near East'', Princeton: Princeton University Press 1980 </ref> | |||

| Already in the winter of 1943-44 Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE) had terminated clandestine arms supplies to the communist-led ELAS-EAM armed resistance movement and stepped up subsidies to the rival EDES populist movement and to the Greek pro-monarchist ruling elite, who posed no threat to capitalism. <ref> LS Stavrianos, "The Greek National Liberation Front (EAM): A Study in Resistance, Organisation and Administration", ''Journal of Modern History'', March 1952, pp.42-55. </ref> ELAS-EAM partisans had during the German occupation of Greece substantially advanced the Allied cause by pinning down about 300,000 German troops, frustrating enemy plans for labour conscription, sabotaging German transportation, supply and communication networks, and rescuing British and American pilots who had been shot down. On the political front, as a precursor to the planned establishment of a socialist republic in Greece, ELAS-EAM had set up socialist structures in the countryside, which the Americans with British encouragement now dismantled in their entirety. <ref> Prokopis Papastratis, "The British and the Greek Resistance Movements EAM and EDES", in Marion Sarafis (ed.), ''Greece: From Resistance to Civil War'', Nottingham: Spokesman 1980, p.36. </ref> This was in clear violation of the Atlantic Charter, which Churchill and Roosevelt had signed in August 1941 as a declaration of respect for "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live". The promise of freedom from despotic rule had effectively lured communist-led partisans and national independence movements everywhere to align themselves with the West in the fight against Germany and Japan. | |||

| ===Italy=== | |||

| Much the same occurred in post-war Italy. In March 1945, months before Germany officially capitulated in Europe, a series of secret negotiations codenamed Operation Sunrise commenced in Switzerland between representatives of the Western Allies and representatives of the German High Command in Italy, headed by General Karl Wolff, commander of the SS or ''Schutzstaffel'') in northern Italy. <ref> Bradley F Smith and Elena Agarossi, ''Operation Sunrise: The Secret Surrender'', New York, 1979. </ref> The objective of these meetings behind the back of the Soviet Union was to forestall a takeover by Italian communist resistance forces in northern Italy and to hinder the potential there for post-war influence of the civilian communist party. <ref>R Harris Smith, ''OSS'', Berkely: University of California Press, 1972, pp.114-121 </ref> The outcome of these meetings was a surrender to the Western Allies on 2 May 1945 of nearly 1,000,000 troops from 22 German and six Italian Fascist divisions in northern Italy, before the war in the rest of Europe had ended. | |||

| Operation Sunrise had been coordinated principally by American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) head Allen Dulles, who was later to become director of the US Central Intelligence Agency. <ref>R Harris Smith, op cit, p.363. </ref> The Germans took advantage of an agreed suspension of hostilities during the secret meetings to transport several army divisions from northern Italy to the Soviet front where the Red Army was still in the process of advancing on Berlin. <ref> Richardson, op cit, p.255. </ref> The affair caused a major rift between Stalin and Churchill, and in a letter to Roosevelt on 3 April Stalin complained that the secret negotiations did not serve to “preserve and promote trust between our countries.”<ref>Richardson, op cit, p.264. </ref> Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio, fascist Italy's former Chief of General Staff and number one on the United Nations list of war criminals, was welcomed ceremoniously by the Western Allies as a "co-belligerent". His "honourable capitulation" from the Axis had been secured on the understanding that Badoglio’s past crimes would simply be wiped off the slate. <ref> Simpson, Christopher, ''Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988, p.91. </ref> Dulles, in return for their early surrender to the West and to the West alone, had promised the German negotiators that none of them would be prosecuted for war crimes. One of the principal participants in the negotiations was Milan Gestapo chief Walter Rauff whose responsibility under the Nazis was to conduct anti-communist operations in Italy. <ref> Harris Smith pp.117, 119 </ref> He was recruited by Dulles to work for OSS and was later assisted by Dulles’s contacts to escaped from Italy to Argentine as a fugitive from war crimes prosecution. <ref> Declassified US intelligence files quoted by investigator John Loftus, ''Boston Globe'', 28 May 1984</ref> | |||

| The Americans proceeded to subsidise and install a regime of collaborators and Nazi sympathizers, while the role in civil society of former anti-fascist partisans was quickly nullified by the Allied Military Government in Occupied Territories and by the Allied Control Commission. Communist and liberal elements, particularly those in the Italian labour movement, became radically marginalised. <ref> Wittner, op cit., </ref> | |||

| ===Far East=== | |||

| The communist-led Malay People’s Anti-Japanese Army had operated in every Malay state during the war against Japan, harassing the Japanese army of occupation with hit-and-run guerrilla warfare. <ref> Spenser Chapman, ''The Jungle is Neutral'', London: Chatto and Windus, 1948; Ian Trenowden, ''Operations Most Secret: SOE, the Malayan Theatre'', London: Wm Kimber, 1978 </ref> By the end of the war, the MPAJA mustered a total of about 4,000 surviving guerrillas supported by tens of thousands of sympathizers and were keen after the war to gain independence from British colonial administration and form a government of their own choosing. <ref> Association of Asian Studies, "Anti-Japanese Movements in Southeast Asia during World War II". Abstract (1996) http://www.aasianst.org;Yoji Akashi, "MPAJA/Force 136 Resistance Against the Japanese in Malaya, 1941-1945". Association of Asian Studies. Abstract (1996) http://www.aasianst.org. </ref> After the war ended, Britain reneged on its promise of independence made in the Atlantic Charter three years earlier, and Malaya was plunged into a state of emergency as British and Commonwealth forces fought a protracted counter-insurgency war against their former communist-led MPAJA ally who now demanded independence from Britain. <ref>Frank Kitson, ''Low Intensity Operations: Subversion, Insurgency and Peacekeeping'', London: Faber, 1971. </ref> | |||

| Elsewhere in the Far East, even before the ink was properly dry on the Japanese surrender agreement, Britain had swiftly transported fully armed Japanese troops to Indonesia, and also to Vietnam, where the Japanese were encouraged to fight with renewed vigour against the former, anti-Japanese resistance groups. <ref> Christopher Thorne, Allies of a Kind: The United States, Britain and the War against Japan, 1941-1945, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1978 </ref> There they joined former Vichy French forces who had collaborated with the Axis during the war and were similarly recruited to remain in Vietnam and fight the indigenous communist Viet Minh led by Ho Chi Minh. <ref>Winer, op cit, p.110 </ref> In British Hong Kong, which had surrendered to Japan in December 1941, civil unrest smouldered after Britain rapidly re-established colonial rule at the end of the war. The British colonial authorities did so without inviting into the administration of the territory any of the more than 6,000 ethnic Chinese guerrillas who had picked up weapons abandoned in the wake of the British retreat and surrender, and waged a war of resistance against the Japanese for the duration of the occupation. <ref>Philip Snow, ''The Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China, and the Japanese Occupation'', Yale University Press: 2003. </ref> In the Philippines, the Americans were similarly fighting their former communist allies who now demanded national self-determination. In China, the Western crusade against national liberation forces proceeded apace. The Commanding General of US Forces, General Albert C Wedemeyer noted that the post-war disarming of Japanese troops by the Chinese had failed "to move smoothly" because fully armed Japanese forces were being employed to fight the West’s former ally, Mao Tse Tung and his communist guerrilla army. <ref>''Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan'', (9 vols) Tokyo and New York: Dondasha 1983, Vol VII, p.202. </ref> In Truman's words: "If we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison ...” <ref> Harry S Truman, ''Memoirs'', (2 vols), New York: Doubleday 1956, Vol II, p.66. </ref> | |||

| ⚫ | ==Tensions build== | ||

| {{see|Long Telegram|Iron Curtain|Restatement of Policy on Germany}} | {{see|Long Telegram|Iron Curtain|Restatement of Policy on Germany}} | ||

| In February 1946, ]'s "]" from Moscow helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, and became the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union for the duration of the Cold War.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kennan|1968|p=292–295}}</ref> That September, the Soviet side produced the ] telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by ]; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war".<ref>{{Harvnb|Kydd|2005|p=107}}</ref> | In February 1946, ]'s "]" from Moscow helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, and became the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union for the duration of the Cold War.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kennan|1968|p=292–295}}</ref> That September, the Soviet side produced the ] telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by ]; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war".<ref>{{Harvnb|Kydd|2005|p=107}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 16:42, 14 March 2010

For other uses, see Cold War (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| History of the Cold War |

|---|

|

| Origins |

| Periods |

| Related topics |

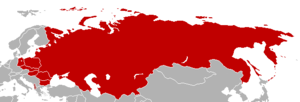

The Cold War (Template:Lang-ru) (1947–1991) was the continuing state of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition existing after World War II (1939–1945), primarily between the USSR and its satellite states, and the powers of the Western world, particularly the United States. Although the primary participants' military forces never officially clashed directly, they expressed the conflict through military coalitions, strategic conventional force deployments, extensive aid to states deemed vulnerable, proxy wars, espionage, propaganda, a nuclear arms race, economic and technological competitions, such as the Space Race.

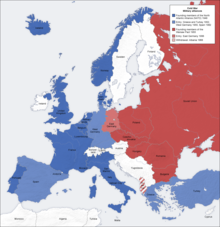

Despite being allies against the Axis powers and having the most powerful military forces among peer nations, the USSR and the US disagreed about the configuration of the post-war world while occupying most of Europe. The Soviet Union created the Eastern Bloc with the eastern European countries it occupied, annexing some as Soviet Socialist Republics and maintaining others as satellite states, some of which were later consolidated as the Warsaw Pact (1955–1991). The US and some western European countries established containment of communism as a defensive policy, establishing alliances such as NATO to that end.

Several such countries also coordinated the Marshall Plan, especially in West Germany, which the USSR opposed. Elsewhere, in Latin America and Southeast Asia, the USSR assisted and helped foster communist revolutions, opposed by several western countries and their regional allies; some they attempted to roll back, with mixed results. Some countries aligned with NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and others formed the Non-Aligned Movement.

The Cold War featured periods of relative calm and of international high tension – the Berlin Blockade (1948–1949), the Korean War (1950–1953), the Berlin Crisis of 1961, the Vietnam War (1959–1975), the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), the Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979–1989), and the Able Archer 83 NATO exercises in November 1983. Both sides sought détente to relieve political tensions and deter direct military attack, which would likely guarantee their mutual assured destruction with nuclear weapons.

In the 1980s, the United States increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressures against the USSR, which had already suffered severe economic stagnation. Thereafter, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev introduced the liberalizing reforms of perestroika ("reconstruction", "reorganization", 1987) and glasnost ("openness", ca. 1985). The Cold War ended after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, leaving the United States as the dominant military power, and Russia possessing most of the Soviet Union's nuclear arsenal. The Cold War and its events have had a significant impact on the world today, and it is commonly referred to in popular culture.

Origins of the term

The first use of the term Cold War describing the post–World War II geopolitical tensions between the USSR and its Western European Allies is attributed to Bernard Baruch, a US financier and presidential advisor. In South Carolina, on April 16, 1947, he delivered a speech (by journalist Herbert Bayard Swope) saying, “Let us not be deceived: we are today in the midst of a cold war.” Newspaper reporter-columnist Walter Lippmann gave the term wide currency, with the book Cold War (1947).

Previously, during the war, George Orwell used the term Cold War in the essay “You and the Atomic Bomb” published October 19, 1945, in the British newspaper Tribune. Contemplating a world living in the shadow of the threat of nuclear war, he warned of a “peace that is no peace”, which he called a permanent “cold war”, Orwell directly referred to that war as the ideological confrontation between the Soviet Union and the Western powers. Moreover, in The Observer of March 10, 1946, Orwell wrote that “. . . fter the Moscow conference last December, Russia began to make a ‘cold war’ on Britain and the British Empire.”

Background

Main article: Origins of the Cold War Further information: Red Scare

There is disagreement among historians regarding the starting point of the Cold War. While most historians trace its origins to the period immediately following World War II, others argue that it began towards the end of World War I, although tensions between the Russian Empire, other European countries and the United States date back to the middle of the 19th century.

As a result of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia (followed by its withdrawal from World War I), Soviet Russia found itself isolated in international diplomacy. Leader Vladimir Lenin stated that the Soviet Union was surrounded by a "hostile capitalist encirclement", and he viewed diplomacy as a weapon to keep Soviet enemies divided, beginning with the establishment of the Soviet Comintern, which called for revolutionary upheavals abroad.

Subsequent leader Joseph Stalin, who viewed the Soviet Union as a "socialist island", stated that the Soviet Union must see that "the present capitalist encirclement is replaced by a socialist encirclement." As early as 1925, Stalin stated that he viewed international politics as a bipolar world in which the Soviet Union would attract countries gravitating to socialism and capitalist countries would attract states gravitating toward capitalism, while the world was in a period of "temporary stabilization of capitalism" preceding its eventual collapse.

Several events fueled suspicion and distrust between the western powers and the Soviet Union: the Bolsheviks' challenge to capitalism; the 1926 Soviet funding of a British general workers strike causing Britain to break relations with the Soviet Union; Stalin's 1927 declaration that peaceful coexistence with "the capitalist countries . . . is receding into the past"; conspiratorial allegations in the Shakhty show trial of a planned French and British-led coup d'etat; the Great Purge involving a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in which over half a million Soviets were executed; the Moscow show trials including allegations of British, French, Japanese and German espionage; the controversial death of 6-8 million people in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the 1932-3 Ukrainian famine; western support of the White Army in the Russian Civil War; the US refusal to recognize the Soviet Union until 1933; and the Soviet entry into the Treaty of Rapallo. This outcome rendered Soviet–American relations a matter of major long-term concern for leaders in both countries.

World War II and post-war (1939–47)

Main article: Origins of the Cold WarMolotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939-41)

Further information: Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and Nazi–Soviet economic relations (1934–1941)Soviet relations with the West further deteriorated when, one week prior to the start of the World War II, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which included a secret agreement to split Poland and Eastern Europe between the two states. Beginning one week later, in September 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union divided Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe through invasions of the countries ceded to each under the Pact.

For the next year and a half, they engaged in an extensive economic relationship, trading vital war materials until Germany broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union through the territories that the two countries had previously divided.

Allies against the Axis (1941-45)

Further information: Eastern Front (World War II), Western Front (World War II), and Lend-LeaseDuring their joint war effort, which began thereafter in 1941, the Soviets suspected that the British and the Americans had conspired to allow the Soviets to bear the brunt of the fighting against Nazi Germany. According to this view, the Western Allies had deliberately delayed opening a second anti-German front in order to step in at the last moment and shape the peace settlement. Thus, Soviet perceptions of the West left a strong undercurrent of tension and hostility between the Allied powers.

Wartime conferences regarding post-war Europe

The Allies disagreed about how the European map should look, and how borders would be drawn, following the war. Each side held dissimilar ideas regarding the establishment and maintenance of post-war security. The western Allies desired a security system in which democratic governments were established as widely as possible, permitting countries to peacefully resolve differences through international organizations.

Following Russian historical experiences with frequent invasions and the immense death toll (estimated at 27 million) and destruction the Soviet Union sustained during World War II, the Soviet Union sought to increase security by controlling the internal affairs of countries that bordered it. In April 1945, both Churchill and new American President Harry S. Truman opposed, among other things, the Soviets' decision to prop up the Lublin government, the Soviet-controlled rival to the Polish government-in-exile, whose relations with the Soviets were severed.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Allies failed to reach a firm consensus on the framework for post-war settlement in Europe. Following the Allied victory in May, the Soviets effectively occupied Eastern Europe, while strong US and Western allied forces remained in Western Europe.

The Soviet Union, United States, Britain and France established zones of occupation and a loose framework for four-power control of occupied Germany. The Allies set up the United Nations for the maintenance of world peace, but the enforcement capacity of its Security Council was effectively paralyzed by individual members' ability to use veto power. Accordingly, the UN was essentially converted into an inactive forum for exchanging polemical rhetoric, and the Soviets regarded it almost exclusively as a propaganda tribune.

Beginnings of the Eastern Bloc

Further information: Eastern BlocDuring the final stages of the war, the Soviet Union laid the foundation for the Eastern Bloc by directly annexing several countries as Soviet Socialist Republics that were initially (and effectively) ceded to it by Nazi Germany in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. These included eastern Poland (incorporated into two different SSRs), Latvia (which became the Latvian SSR), Estonia (which became the Estonian SSR), Lithuania (which became the Lithuanian SSR), part of eastern Finland (which became the Karelo-Finnish SSR) and eastern Romania (which became the Moldavian SSR).

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was concerned that, given the enormous size of Soviet forces deployed in Europe at the end of the war, and the perception that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was unreliable, there existed a Soviet threat to Western Europe. In April-May 1945, the British War Cabinet's Joint Planning Staff Committee developed Operation Unthinkable, a plan "to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire". The plan, however, was rejected by the British Chiefs of Staff Committee as militarily unfeasible.

Potsdam Conference and defeat of Japan

At the Potsdam Conference, which started in late July after Germany's surrender, serious differences emerged over the future development of Germany and eastern Europe. Moreover, the participants' mounting antipathy and bellicose language served to confirm their suspicions about each others' hostile intentions and entrench their positions. At this conference Truman informed Stalin that the United States possessed a powerful new weapon.

Stalin was aware that the Americans were working on the atomic bomb and, given that the Soviets' own rival program was in place, he reacted to the news calmly. The Soviet leader said he was pleased by the news and expressed the hope that the weapon would be used against Japan. One week after the end of the Potsdam Conference, the US bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Shortly after the attacks, Stalin protested to US officials when Truman offered the Soviets little real influence in occupied Japan.

Early blows in the political Cold War

Greece

In Greece the American intelligence community took virtual control of the country’s entire post-war social, political, military and economic structures. These were planned, decided and executed by the American Mission in Greece, including support for pro-Nazi Greeks who had hunted down partisans and participated in the mass murder of about 70,000 Greek Jews during the war. Greek civil liberties were eroded, the communist-led former partisan movement ELAS-EAM was all but destroyed, pro-monarchist armed forces were greatly strengthened, the trade union movement completely undermined, and a virulent anti-communist swing manipulated in Greek affairs as a whole.

Already in the winter of 1943-44 Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE) had terminated clandestine arms supplies to the communist-led ELAS-EAM armed resistance movement and stepped up subsidies to the rival EDES populist movement and to the Greek pro-monarchist ruling elite, who posed no threat to capitalism. ELAS-EAM partisans had during the German occupation of Greece substantially advanced the Allied cause by pinning down about 300,000 German troops, frustrating enemy plans for labour conscription, sabotaging German transportation, supply and communication networks, and rescuing British and American pilots who had been shot down. On the political front, as a precursor to the planned establishment of a socialist republic in Greece, ELAS-EAM had set up socialist structures in the countryside, which the Americans with British encouragement now dismantled in their entirety. This was in clear violation of the Atlantic Charter, which Churchill and Roosevelt had signed in August 1941 as a declaration of respect for "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live". The promise of freedom from despotic rule had effectively lured communist-led partisans and national independence movements everywhere to align themselves with the West in the fight against Germany and Japan.

Italy

Much the same occurred in post-war Italy. In March 1945, months before Germany officially capitulated in Europe, a series of secret negotiations codenamed Operation Sunrise commenced in Switzerland between representatives of the Western Allies and representatives of the German High Command in Italy, headed by General Karl Wolff, commander of the SS or Schutzstaffel) in northern Italy. The objective of these meetings behind the back of the Soviet Union was to forestall a takeover by Italian communist resistance forces in northern Italy and to hinder the potential there for post-war influence of the civilian communist party. The outcome of these meetings was a surrender to the Western Allies on 2 May 1945 of nearly 1,000,000 troops from 22 German and six Italian Fascist divisions in northern Italy, before the war in the rest of Europe had ended.

Operation Sunrise had been coordinated principally by American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) head Allen Dulles, who was later to become director of the US Central Intelligence Agency. The Germans took advantage of an agreed suspension of hostilities during the secret meetings to transport several army divisions from northern Italy to the Soviet front where the Red Army was still in the process of advancing on Berlin. The affair caused a major rift between Stalin and Churchill, and in a letter to Roosevelt on 3 April Stalin complained that the secret negotiations did not serve to “preserve and promote trust between our countries.” Field Marshal Pietro Badoglio, fascist Italy's former Chief of General Staff and number one on the United Nations list of war criminals, was welcomed ceremoniously by the Western Allies as a "co-belligerent". His "honourable capitulation" from the Axis had been secured on the understanding that Badoglio’s past crimes would simply be wiped off the slate. Dulles, in return for their early surrender to the West and to the West alone, had promised the German negotiators that none of them would be prosecuted for war crimes. One of the principal participants in the negotiations was Milan Gestapo chief Walter Rauff whose responsibility under the Nazis was to conduct anti-communist operations in Italy. He was recruited by Dulles to work for OSS and was later assisted by Dulles’s contacts to escaped from Italy to Argentine as a fugitive from war crimes prosecution.

The Americans proceeded to subsidise and install a regime of collaborators and Nazi sympathizers, while the role in civil society of former anti-fascist partisans was quickly nullified by the Allied Military Government in Occupied Territories and by the Allied Control Commission. Communist and liberal elements, particularly those in the Italian labour movement, became radically marginalised.

Far East

The communist-led Malay People’s Anti-Japanese Army had operated in every Malay state during the war against Japan, harassing the Japanese army of occupation with hit-and-run guerrilla warfare. By the end of the war, the MPAJA mustered a total of about 4,000 surviving guerrillas supported by tens of thousands of sympathizers and were keen after the war to gain independence from British colonial administration and form a government of their own choosing. After the war ended, Britain reneged on its promise of independence made in the Atlantic Charter three years earlier, and Malaya was plunged into a state of emergency as British and Commonwealth forces fought a protracted counter-insurgency war against their former communist-led MPAJA ally who now demanded independence from Britain.

Elsewhere in the Far East, even before the ink was properly dry on the Japanese surrender agreement, Britain had swiftly transported fully armed Japanese troops to Indonesia, and also to Vietnam, where the Japanese were encouraged to fight with renewed vigour against the former, anti-Japanese resistance groups. There they joined former Vichy French forces who had collaborated with the Axis during the war and were similarly recruited to remain in Vietnam and fight the indigenous communist Viet Minh led by Ho Chi Minh. In British Hong Kong, which had surrendered to Japan in December 1941, civil unrest smouldered after Britain rapidly re-established colonial rule at the end of the war. The British colonial authorities did so without inviting into the administration of the territory any of the more than 6,000 ethnic Chinese guerrillas who had picked up weapons abandoned in the wake of the British retreat and surrender, and waged a war of resistance against the Japanese for the duration of the occupation. In the Philippines, the Americans were similarly fighting their former communist allies who now demanded national self-determination. In China, the Western crusade against national liberation forces proceeded apace. The Commanding General of US Forces, General Albert C Wedemeyer noted that the post-war disarming of Japanese troops by the Chinese had failed "to move smoothly" because fully armed Japanese forces were being employed to fight the West’s former ally, Mao Tse Tung and his communist guerrilla army. In Truman's words: "If we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison ...”

Tensions build

Further information: Long Telegram, Iron Curtain, and Restatement of Policy on GermanyIn February 1946, George F. Kennan's "Long Telegram" from Moscow helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, and became the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union for the duration of the Cold War. That September, the Soviet side produced the Novikov telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by Vyacheslav Molotov; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war".

On September 6, 1946, James F. Byrnes delivered a speech in Germany repudiating the Morgenthau Plan (a proposal to partition and de-industrialize post-war Germany) and warning the Soviets that the US intended to maintain a military presence in Europe indefinitely. As Byrnes admitted a month later, "The nub of our program was to win the German people it was a battle between us and Russia over minds "

A few weeks after the release of this "Long Telegram", former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech in Fulton, Missouri. The speech called for an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets, whom he accused of establishing an "iron curtain" from "Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic".

Containment through the Korean War (1947–53)

Main article: Cold War (1947–1953)Soviet satellite states

After annexing several occupied countries as Soviet Socialist Republics at the end of World War II, other occupied states were added to the Eastern Bloc by converting them into puppet Soviet Satellite states, such as East Germany, the People's Republic of Poland, the People's Republic of Hungary, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, the People's Republic of Romania and the People's Republic of Albania.

The Soviet-style regimes that arose in the Bloc not only reproduced Soviet command economies, but also adopted the brutal methods employed by Joseph Stalin and Soviet secret police to suppress real and potential opposition. In Asia, the Red Army had overrun Manchuria in the last month of the war, and went on to occupy the large swath of Korean territory located north of the 38th parallel.

In September 1947, the Soviets created Cominform, the purpose of which was to enforce orthodoxy within the international communist movement and tighten political control over Soviet satellites through coordination of communist parties in the Eastern Bloc. Cominform faced an embarrassing setback the following June, when the Tito–Stalin split obliged its members to expel Yugoslavia, which remained Communist but adopted a non-aligned position.

As part of the Soviet domination of the Eastern Bloc, the NKVD, led by Lavrentiy Beria, supervised the establishment of Soviet-style secret police systems in the Bloc that were supposed to crush anti-communist resistance. When the slightest stirrings of independence emerged in the Bloc, Stalin's strategy matched that of dealing with domestic pre-war rivals: they were removed from power, put on trial, imprisoned, and in several instances, executed.

Containment and the Truman Doctrine

By 1947, US president Harry S. Truman's advisers urged him to take immediate steps to counter the Soviet Union's influence, citing Stalin's efforts (amid post-war confusion and collapse) to undermine the US by encouraging rivalries among capitalists that could precipitate another war. In February 1947, the British government announced that it could no longer afford to finance the Greek monarchical military regime in its civil war against communist-led insurgents.

The American government's response to this announcement was the adoption of containment, the goal of which was to stop the spread of communism. Truman delivered a speech that called for the allocation of $400 million to intervene in the war and unveiled the Truman Doctrine, which framed the conflict as a contest between free peoples and totalitarian regimes. Even though the insurgents were helped by Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia, US policymakers accused the Soviet Union of conspiring against the Greek royalists in an effort to expand Soviet influence.

Enunciation of the Truman Doctrine marked the beginning of a US bipartisan defense and foreign policy consensus between Republicans and Democrats focused on containment and deterrence that weakened during and after the Vietnam War, but ultimately held steady. Moderate and conservative parties in Europe, as well as social democrats, gave virtually unconditional support to the Western alliance, while European and American Communists, paid by the KGB and involved in its intelligence operations, adhered to Moscow's line, although dissent began to appear after 1956. Other critiques of consensus politics came from anti-Vietnam War activists, the CND and the nuclear freeze movement.

Marshall Plan and Czechoslovak coup d'état

In early 1947, Britain, France and the United States unsuccessfully attempted to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union for a plan envisioning an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, goods and infrastructure already removed by the Soviets. In June 1947, in accordance with the Truman Doctrine, the United States enacted the Marshall Plan, a pledge of economic assistance for all European countries willing to participate, including the Soviet Union.

The plan's aim was to rebuild the democratic and economic systems of Europe and to counter perceived threats to Europe's balance of power, such as communist parties seizing control through revolutions or elections. The plan also stated that European prosperity was contingent upon German economic recovery. One month later, Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, creating a unified Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the National Security Council. These would become the main bureaucracies for US policy in the Cold War.

Stalin believed that economic integration with the West would allow Eastern Bloc countries to escape Soviet control, and that the US was trying to buy a pro-US re-alignment of Europe. Stalin therefore prevented Eastern Bloc nations from receiving Marshall Plan aid. The Soviet Union's alternative to the Marshall plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with eastern Europe, became known as the Molotov Plan (later institutionalized in January 1949 as the Comecon). Stalin was also fearful of a reconstituted Germany; his vision of a post-war Germany did not include the ability to rearm or pose any kind of threat to the Soviet Union.

In early 1948, following reports of strengthening "reactionary elements", Soviet operatives executed a coup d'état of 1948 in Czechoslovakia, the only Eastern Bloc state that the Soviets had permitted to retain democratic structures. The public brutality of the coup shocked Western powers more than any event up to that point, set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.

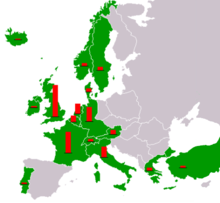

The twin policies of the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan led to billions in economic and military aid for Western Europe, and Greece and Turkey. With US assistance, the Greek military won its civil war, The Italian Christian Democrats defeated the powerful Communist-Socialist alliance in the elections of 1948. Increases occurred in intelligence and espionage activities, Eastern Bloc defections and diplomatic expulsions.

Berlin Blockade and airlift

The United States and Britain merged their western German occupation zones into "Bizonia" (later "trizonia" with the addition of France's zone). As part of the economic rebuilding of Germany, in early 1948, representatives of a number of Western European governments and the United States announced an agreement for a merger of western German areas into a federal governmental system. In addition, in accordance with the Marshall Plan, they began to re-industrialize and rebuild the German economy, including the introduction of a new Deutsche Mark currency to replace the old Reichsmark currency that the Soviets had debased.

Shortly thereafter, Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade, one of the first major crises of the Cold War, preventing food, materials and supplies from arriving in West Berlin. The United States, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several other countries began the massive "Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with food and other provisions.

The Soviets mounted a public relations campaign against the policy change, communists attempted to disrupt the elections of 1948 preceding large losses therein, 300,000 Berliners demonstrated and urged the international airlift to continue, and the US accidentally created "Operation Vittles", which supplied candy to German children. In May 1949, Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade.

NATO beginnings and Radio Free Europe

Main articles: NATO, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and Eastern Bloc information dissemination

Britain, France, the United States, Canada and eight other western European countries signed the North Atlantic Treaty of April 1949, establishing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). That August, Stalin ordered the detonation of the first Soviet atomic device. Following Soviet refusals to participate in a German rebuilding effort set forth by western European countries in 1948, the US, Britain and France spearheaded the establishment of West Germany from the three Western zones of occupation in May 1949. The Soviet Union proclaimed its zone of occupation in Germany the German Democratic Republic that October.

Media in the Eastern Bloc was an organ of the state, completely reliant on and subservient to the communist party, with radio and television organizations being state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local communist party. Soviet propaganda used Marxist philosophy to attack capitalism, claiming labor exploitation and war-mongering imperialism were inherent in the system.

Along with the broadcasts of the British Broadcasting Company and the Voice of America to Eastern Europe, a major propaganda effort begun in 1949 was Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, dedicated to bringing about the peaceful demise of the Communist system in the Eastern Bloc. Radio Free Europe attempted to achieve these goals by serving as a surrogate home radio station, an alternative to the controlled and party-dominated domestic press. Radio Free Europe was a product of some of the most prominent architects of America's early Cold War strategy, especially those who believed that the Cold War would eventually be fought by political rather than military means, such as George F. Kennan.

American policymakers, including Kennan and John Foster Dulles, acknowledged that the Cold War was in its essence a war of ideas. The United States, acting through the CIA, funded a long list of projects to counter the Communist appeal among intellectuals in Europe and the developing world.

In the early 1950s, the US worked for the rearmament of West Germany and, in 1955, secured its full membership of NATO. In May 1953, Beria, by then in a government post, had made an unsuccessful proposal to allow the reunification of a neutral Germany to prevent West Germany's incorporation into NATO.

Chinese Civil War and SEATO

Further information: Chinese Civil War and Southeast Asia Treaty OrganizationIn 1949, Mao's People's Liberation Army defeated Chiang's US-backed Kuomintang (KMT) Nationalist Government in China, and the Soviet Union promptly created an alliance with the newly-formed People's Republic of China. The Nationalist Government retreated to the island of Taiwan. Confronted with the Communist takeover of mainland China and the end of the US atomic monopoly in 1949, the Truman administration quickly moved to escalate and expand the containment policy. In NSC-68, a secret 1950 document, the National Security Council proposed to reinforce pro-Western alliance systems and quadruple spending on defense.

US officials moved thereafter to expand containment into Asia, Africa, and Latin America, in order to counter revolutionary nationalist movements, often led by Communist parties financed by the USSR, fighting against the restoration of Europe's colonial empires in South-East Asia and elsewhere. In the early 1950s (a period sometimes known as the "Pactomania"), the US formalized a series of alliances with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the Philippines (notably ANZUS and SEATO), thereby guaranteeing the United States a number of long-term military bases.

Korean War

Main article: Korean WarOne of the more significant impacts of containment was the outbreak of the Korean War. In June 1950, Kim Il-Sung's North Korean People's Army invaded South Korea. To Stalin's surprise, the UN Security Council backed the defense of South Korea, though the Soviets were then boycotting meetings to protest that Taiwan and not Communist China held a permanent seat on the Council. A UN force of personnel from South Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Canada, Australia, France, the Philippines, the Netherlands, Belgium, New Zealand and other countries joined to stop the invasion.

Among other effects, the Korean War galvanised NATO to develop a military structure. Public opinion in countries involved, such as Great Britain, was divided for and against the war. British Attorney General Sir Hartley Shawcross repudiated the sentiment of those opposed when he said:

I know there are some who think that the horror and devastation of a world war now would be so frightful, whoever won, and the damage to civilization so lasting, that it would be better to submit to Communist domination. I understand that view–but I reject it.

Even though the Chinese and North Koreans were exhausted by the war and were prepared to end it by late 1952, Stalin insisted that they continue fighting, and a cease-fire was approved only in July 1953, after Stalin's death. In North Korea, Kim Il Sung created a highly centralized and brutal dictatorship, according himself unlimited power and generating a formidable cult of personality.

Crisis and escalation (1953–62)

Main article: Cold War (1953–1962)Khrushchev, Eisenhower and De-Stalinization

In 1953, changes in political leadership on both sides shifted the dynamic of the Cold War. Dwight D. Eisenhower was inaugurated president that January. During the last 18 months of the Truman administration, the US defense budget had quadrupled, and Eisenhower moved to reduce military spending by a third while continuing to fight the Cold War effectively.

In March, following the death of Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev became the Soviet leader following the deposition and execution of Lavrentiy Beria and the pushing aside of rivals Georgy Malenkov and Vyacheslav Molotov. On February 25, 1956, Khrushchev shocked delegates to the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party by cataloguing and denouncing Stalin's crimes. As part of a campaign of de-Stalinization, he declared that the only way to reform and move away from Stalin's policies would be to acknowledge errors made in the past.

On November 18, 1956, while addressing Western ambassadors at a reception at the Polish embassy in Moscow, Khrushchev used his famous "Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you" expression, shocking everyone present. However, he had not been talking about nuclear war, he later claimed, but rather about the historically determined victory of communism over capitalism. He then declared in 1961 that even if the USSR might indeed be behind the West, within a decade its housing shortage would disappear, consumer goods would be abundant, its population would be "materially provided for", and within two decades, the Soviet Union "would rise to such a great height that, by comparison, the main capitalist countries will remain far below and well behind".

Eisenhower's secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, initiated a "New Look" for the containment strategy, calling for a greater reliance on nuclear weapons against US enemies in wartime. Dulles also enunciated the doctrine of "massive retaliation", threatening a severe US response to any Soviet aggression. Possessing nuclear superiority, for example, allowed Eisenhower to face down Soviet threats to intervene in the Middle East during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Warsaw Pact and Hungarian Revolution

Main articles: Warsaw Pact and Hungarian Revolution of 1956

While Stalin's death in 1953 slightly relaxed tensions, the situation in Europe remained an uneasy armed truce. The Soviets, who had already created a network of mutual assistance treaties in the Eastern Bloc by 1949, established a formal alliance therein, the Warsaw Pact, in 1955.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 occurred shortly after Khrushchev arranged the removal of Hungary's Stalinist leader Mátyás Rákosi. In response to a popular uprising, the new regime formally disbanded the secret police, declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and pledged to re-establish free elections. The Soviet Red Army invaded. Thousands of Hungarians were arrested, imprisoned and deported to the Soviet Union, and approximately 200,000 Hungarians fled Hungary in the chaos. Hungarian leader Imre Nagy and others were executed following secret trials.

From 1957 through 1961, Khrushchev openly and repeatedly threatened the West with nuclear annihilation. He claimed that Soviet missile capabilities were far superior to those of the United States, capable of wiping out any American or European city. However, Khrushchev rejected Stalin's belief in the inevitability of war, and declared his new goal was to be "peaceful coexistence". This formulation modified the Stalin-era Soviet stance, where international class struggle meant the two opposing camps were on an inevitable collision course where Communism would triumph through global war; now, peace would allow capitalism to collapse on its own, as well as giving the Soviets time to boost their military capabilities, which remained for decades until Gorbachev's later "new thinking" envisioning peaceful coexistence as an end in itself rather than a form of class struggle.

US pronouncements concentrated on American strength abroad and the success of liberal capitalism. However, by the late 1960s, the "battle for men's minds" between two systems of social organization that Kennedy spoke of in 1961 was largely over, with tensions henceforth based primarily on clashing geopolitical objectives rather than ideology.

Berlin ultimatum and European integration

During November 1958, Khrushchev made an unsuccessful attempt to turn all of Berlin into an independent, demilitarized "free city", giving the United States, Great Britain, and France a six-month ultimatum to withdraw their troops from the sectors they still occupied in West Berlin, or he would transfer control of Western access rights to the East Germans. Khrushchev earlier explained to Mao Tse-tung that "Berlin is the testicles of the West. Every time I want to make the West scream, I squeeze on Berlin." NATO formally rejected the ultimatum in mid-December and Khrushchev withdrew it in return for a Geneva conference on the German question.

More broadly, one hallmark of the 1950s was the beginning of European integration—a fundamental by-product of the Cold War that Truman and Eisenhower promoted politically, economically, and militarily, but which later administrations viewed ambivalently, fearful that an independent Europe would forge a separate détente with the Soviet Union, which would use this to exacerbate Western disunity.

Worldwide competition

Nationalist movements in some countries and regions, notably Guatemala, Iran, the Philippines, and Indochina were often allied with communist groups—or at least were perceived in the West to be allied with communists. In this context, the US and the Soviet Union increasingly competed for influence by proxy in the Third World as decolonization gained momentum in the 1950s and early 1960s; additionally, the Soviets saw continuing losses by imperial powers as presaging the eventual victory of their ideology.

The US government utilized the CIA in order to remove a string of unfriendly Third World governments and to support allied ones. The US used the CIA to overthrow governments suspected by Washington of turning pro-Soviet, including Iran's first democratically elected government under Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq in 1953 (see 1953 Iranian coup d'état) and Guatemala's democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán in 1954 (see 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état). Between 1954 and 1961, the US sent economic aid and military advisors to stem the collapse of South Vietnam's pro-Western regime.

Many emerging nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America rejected the pressure to choose sides in the East-West competition. In 1955, at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, dozens of Third World governments resolved to stay out of the Cold War. The consensus reached at Bandung culminated with the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. Meanwhile, Khrushchev broadened Moscow's policy to establish ties with India and other key neutral states. Independence movements in the Third World transformed the post-war order into a more pluralistic world of decolonized African and Middle Eastern nations and of rising nationalism in Asia and Latin America.

Sino-Soviet split, space race, ICBMs

The period after 1956 was marked by serious setbacks for the Soviet Union, most notably the breakdown of the Sino-Soviet alliance, beginning the Sino-Soviet split. Mao had defended Stalin when Khrushchev attacked him after his death in 1956, and treated the new Soviet leader as a superficial upstart, accusing him of having lost his revolutionary edge.

After this, Khrushchev made many desperate attempts to reconstitute the Sino-Soviet alliance, but Mao considered it useless and denied any proposal. The Chinese and the Soviets waged an intra-Communist propaganda war. Further on, the Soviets focused on a bitter rivalry with Mao's China for leadership of the global communist movement, and the two clashed militarily in 1969.

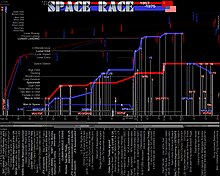

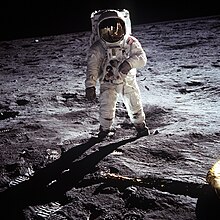

On the nuclear weapons front, the US and the USSR pursued nuclear rearmament and developed long-range weapons with which they could strike the territory of the other. In August 1957, the Soviets successfully launched the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and in October, launched the first Earth satellite, Sputnik. The launch of Sputnik inaugurated the Space Race. This culminated in the Apollo Moon landings, which astronaut Frank Borman later described as "just a battle in the Cold War" with superior spaceflight rockets indicating superior ICBMs.

Berlin Crisis of 1961

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 was the last major incident in the Cold War regarding the status of Berlin and post-World War II Germany. By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to restricting emigration movement was emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc. However, hundreds of thousands of East Germans annually emigrated to West Germany through a "loophole" in the system that existed between East and West Berlin, where the four occupying World War II powers governed movement.

The emigration resulted in a massive "brain drain" from East Germany to West Germany of younger educated professionals, such that nearly 20% of East Germany's population had migrated to West Germany by 1961. That June, the Soviet Union issued a new ultimatum demanding the withdrawal of Allied forces from West Berlin. The request was rebuffed, and in August, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded through construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.

Cuban Missile Crisis and Khrushchev ouster

Main article: Cuban Missile CrisisThe Soviet Union formed an alliance with Fidel Castro-led Cuba after the Cuban Revolution in 1959. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy responded to the installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba with a naval blockade. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than ever before. It further demonstrated the concept of mutually assured destruction, that neither nuclear power was prepared to use nuclear weapons fearing total destruction via nuclear retaliation. The aftermath of the crisis led to the first efforts in the nuclear arms race at nuclear disarmament and improving relations, although the Cold War's first arms control agreement, the Antarctic Treaty, had come into force in 1961.

In 1964, Khrushchev's Kremlin colleagues managed to oust him, but allowed him a peaceful retirement. Accused of rudeness and incompetence, he was also credited with ruining Soviet agriculture and bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war. Khrushchev had become an international embarrassment when he authorised construction of the Berlin Wall, a public humiliation for Marxism-Leninism.

Confrontation through détente (1962–79)

Main article: Cold War (1962–1979)

In the course of the 1960s and '70s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs. From the beginning of the post-war period, Western Europe and Japan rapidly recovered from the destruction of World War II and sustained strong economic growth through the 1950s and '60s, with per capita GDPs approaching those of the United States, while Eastern Bloc economies stagnated.

As a result of the 1973 oil crisis, combined with the growing influence of Third World alignments such as the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the Non-Aligned Movement, less-powerful countries had more room to assert their independence and often showed themselves resistant to pressure from either superpower. Moscow, meanwhile, was forced to turn its attention inward to deal with the Soviet Union's deep-seated domestic economic problems. During this period, Soviet leaders such as Alexey Kosygin and Leonid Brezhnev embraced the notion of détente.

Dominican Republic and French NATO withdrawal

Main article: United States invasion of the Dominican RepublicPresident Lyndon B. Johnson landed 22,000 troops in the Dominican Republic in Operation Power Pack, citing the threat of the emergence of a Cuban-style revolution in Latin America. NATO countries remained primarily dependent on the US military for its defense against any potential Soviet invasion, a status most vociferously contested by France's Charles de Gaulle, who in 1966 withdrew from NATO's military structures and expelled NATO troops from French soil.

Czechoslovakia invasion

Main articles: Prague Spring and Warsaw Pact invasion of CzechoslovakiaIn 1968, a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring took place that included "Action Program" of liberalizations, which described increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, along with an economic emphasis on consumer goods, the possibility of a multiparty government, limiting the power of the secret police and potentially withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact.

The Soviet Red Army, together with most of their Warsaw Pact allies, invaded Czechoslovakia. The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, including an estimated 70,000 Czechs initially fleeing, with the total eventually reaching 300,000. The invasion sparked intense protests from Yugoslavia, Romania and China, and from Western European communist parties.

Brezhnev Doctrine

In September 1968, during a speech at the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers' Party one month after the invasion of Czechoslovakia, Brezhnev outlined the Brezhnev Doctrine, in which he claimed the right to violate the sovereignty of any country attempting to replace Marxism-Leninism with capitalism. During the speech, Brezhnev stated:

When forces that are hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist country towards capitalism, it becomes not only a problem of the country concerned, but a common problem and concern of all socialist countries.

The doctrine found its origins in the failures of Marxism-Leninism in states like Poland, Hungary and East Germany, which were facing a declining standard of living contrasting with the prosperity of West Germany and the rest of Western Europe.

Third World escalations

Main articles: Vietnam War, Operation Condor, and Yom Kippur WarThe US continued to spend heavily on supporting friendly Third World regimes in Asia. Conflicts in peripheral regions and client states—most prominently in Vietnam—continued. Johnson stationed 575,000 troops in Southeast Asia to defeat the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) and their North Vietnamese allies in the Vietnam War, but his costly policy weakened the US economy and, by 1975, ultimately culminated in what most of the world saw as a humiliating defeat of the world's most powerful superpower at the hands of one of the world's poorest nations.

Additionally, Operation Condor, employed by South American dictators to suppress leftist dissent, was backed by the US, which (sometimes accurately) perceived Soviet or Cuban support behind these opposition movements. Brezhnev, meanwhile, attempted to revive the Soviet economy, which was declining in part because of heavy military expenditures.

Moreover, the Middle East continued to be a source of contention. Egypt, which received the bulk of its arms and economic assistance from the USSR, was a troublesome client, with a reluctant Soviet Union feeling obliged to assist in both the 1967 Six-Day War (with advisers and technicians) and the War of Attrition (with pilots and aircraft) against US ally Israel; Syria and Iraq later received increased assistance as well as (indirectly) the PLO.

During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, rumors of imminent Soviet intervention on the Egyptians' behalf brought about a massive US mobilization that threatened to wreck détente; this escalation, the USSR's first in a regional conflict central to US interests, inaugurated a new and more turbulent stage of Third World military activism in which the Soviets made use of their new strategic parity.

Sino-American relations

Main article: 1972 Nixon visit to ChinaAs a result of the Sino-Soviet split, tensions along the Chinese-Soviet border reached their peak in 1969, and US President Richard Nixon decided to use the conflict to shift the balance of power towards the West in the Cold War. The Chinese had sought improved relations with the US in order to gain advantage over the Soviets as well.

In February 1972, Nixon announced a stunning rapprochement with Mao's China by traveling to Beijing and meeting with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. At this time, the USSR achieved rough nuclear parity with the US while the Vietnam War weakened US influence in the Third World and cooled relations with Western Europe. Although indirect conflict between Cold War powers continued through the late 1960s and early 1970s, tensions were beginning to ease.

Nixon, Brezhnev, and détente

Following his China visit, Nixon met with Soviet leaders, including Brezhnev in Moscow. These Strategic Arms Limitation Talks resulted in two landmark arms control treaties: SALT I, the first comprehensive limitation pact signed by the two superpowers, and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which banned the development of systems designed to intercept incoming missiles. These aimed to limit the development of costly anti-ballistic missiles and nuclear missiles.

Nixon and Brezhnev proclaimed a new era of "peaceful coexistence" and established the groundbreaking new policy of détente (or cooperation) between the two superpowers. Between 1972 and 1974, the two sides also agreed to strengthen their economic ties, including agreements for increased trade. As a result of their meetings, détente would replace the hostility of the Cold War and the two countries would live mutually.

Meanwhile, these developments coincided with the "Ostpolitik" of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt. Other agreements were concluded to stabilize the situation in Europe, culminating in the Helsinki Accords signed at the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe in 1975.

Late 1970s deterioration of relations

In the 1970s, the KGB, led by Yuri Andropov, continued to persecute distinguished Soviet personalities such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov, who were criticising the Soviet leadership in harsh terms. Indirect conflict between the superpowers continued through this period of détente in the Third World, particularly during political crises in the Middle East, Chile, Ethiopia and Angola.

Although President Jimmy Carter tried to place another limit on the arms race with a SALT II agreement in 1979, his efforts were undermined by the other events that year, including the Iranian Revolution and the Nicaraguan Revolution, which both ousted pro-US regimes, and his retaliation against Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in December.

Second Cold War (1979–85)

The term second Cold War has been used by some historians to refer to the period of intensive reawakening of Cold War tensions and conflicts in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Tensions greatly increased between the major powers with both sides becoming more militaristic.

Afghanistan war

Main article: Soviet war in AfghanistanDuring December 1979, approximately 75,000 Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan in order to support the Marxist government formed by ex-Prime-minister Nur Muhammad Taraki, assassinated that September by one of his party rivals. As a result, US President Jimmy Carter withdrew the SALT II treaty from the Senate, imposed embargoes on grain and technology shipments to the USSR, demanded a significant increase in military spending, and further announced that the United States would boycott the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics. He described the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan as "the most serious threat to the peace since the Second World War".

Reagan and Thatcher

In 1980, Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter in the US presidential election, vowing to increase military spending and confront the Soviets everywhere. Both Reagan and new British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher denounced the Soviet Union and its ideology. Reagan labeled the Soviet Union an "evil empire" and predicted that Communism would be left on the "ash heap of history".

Polish Solidarity movement

Main articles: Solidarity (Polish trade union), Soviet reaction to the Polish Crisis of 1980-1981, and Martial law in PolandPope John Paul II provided a moral focus for anti-communism; a visit to his native Poland in 1979 stimulated a religious and nationalist resurgence centered on the Solidarity movement that galvanized opposition and may have led to his attempted assassination two years later. Reagan also imposed economic sanctions on Poland to protest the suppression of Solidarity. In response, Mikhail Suslov, the Kremlin's top ideologist, advised Soviet leaders not to intervene if Poland fell under the control of Solidarity, for fear it might lead to heavy economic sanctions, representing a catastrophe for the Soviet economy.

Soviet and US military and economic issues

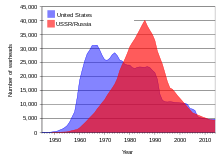

Moscow had built up a military that consumed as much as 25 percent of the Soviet Union's gross national product at the expense of consumer goods and investment in civilian sectors. Soviet spending on the arms race and other Cold War commitments both caused and exacerbated deep-seated structural problems in the Soviet system, which saw at least a decade of economic stagnation during the late Brezhnev years.

Soviet investment in the defense sector was not driven by military necessity, but in large part by the interests of massive party and state bureaucracies dependent on the sector for their own power and privileges. The Soviet Armed Forces became the largest in the world in terms of the numbers and types of weapons they possessed, in the number of troops in their ranks, and in the sheer size of their military–industrial base. However, the quantitative advantages held by the Soviet military often concealed areas where the Eastern Bloc dramatically lagged behind the West.

By the early 1980s, the USSR had built up a military arsenal and army surpassing that of the United States. Previously, the US had relied on the qualitative superiority of its weapons, but the gap had been narrowed. Ronald Reagan began massively building up the United States military not long after taking office. This led to the largest peacetime defense buildup in United States history.

Tensions continued intensifying in the early 1980s when Reagan revived the B-1 Lancer program that was canceled by the Carter administration, produced LGM-118 Peacekeepers, installed US cruise missiles in Europe, and announced his experimental Strategic Defense Initiative, dubbed "Star Wars" by the media, a defense program to shoot down missiles in mid-flight.

With the background of a buildup in tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States, and the deployment of Soviet RSD-10 Pioneer ballistic missiles targeting Western Europe, NATO decided, under the impetus of the Carter presidency, to deploy MGM-31 Pershing and cruise missiles in Europe, primarily West Germany. This deployment would have placed missiles just 10 minutes' striking distance from Moscow.

After Reagan's military buildup, the Soviet Union did not respond by further building its military because the enormous military expenses, along with inefficient planned manufacturing and collectivized agriculture, were already a heavy burden for the Soviet economy. At the same time, Reagan persuaded Saudi Arabia to increase oil production, even as other non-OPEC nations were increasing production. These developments contributed to the 1980s oil glut, which affected the Soviet Union, as oil was the main source of Soviet export revenues. Issues with command economics, oil prices decreases and large military expenditures gradually brought the Soviet economy to stagnation.

On September 1, 1983, the Soviet Union shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, a Boeing 747 with 269 people aboard, including sitting Congressman Larry McDonald, when it violated Soviet airspace just past the west coast of Sakhalin Island—an act which Reagan characterized as a "massacre". This act increased support for military deployment, overseen by Reagan, which stood in place until the later accords between Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. The Able Archer 83 exercise in November 1983, a realistic simulation of a coordinated NATO nuclear release, has been called most dangerous moment since the Cuban Missile Crisis, as the Soviet leadership keeping a close watch on it considered a nuclear attack to be imminent.

US domestic public concerns about intervening in foreign conflicts persisted from the end of the Vietnam War. The Reagan administration emphasized the use of quick, low-cost counter-insurgency tactics to intervene in foreign conflicts. In 1983, the Reagan administration intervened in the multisided Lebanese Civil War, invaded Grenada, bombed Libya and backed the Central American Contras, anti-communist paramilitaries seeking to overthrow the Soviet-aligned Sandinista government in Nicaragua. While Reagan's interventions against Grenada and Libya were popular in the US, his backing of the Contra rebels was mired in controversy.

Meanwhile, the Soviets incurred high costs for their own foreign interventions. Although Brezhnev was convinced in 1979 that the Soviet war in Afghanistan would be brief, Muslim guerrillas, aided by the US and other countries, waged a fierce resistance against the invasion. The Kremlin sent nearly 100,000 troops to support its puppet regime in Afghanistan, leading many outside observers to dub the war "the Soviets' Vietnam". However, Moscow's quagmire in Afghanistan was far more disastrous for the Soviets than Vietnam had been for the Americans because the conflict coincided with a period of internal decay and domestic crisis in the Soviet system.

A senior US State Department official predicted such an outcome as early as 1980, positing that the invasion resulted in part from a "domestic crisis within the Soviet system. ... It may be that the thermodynamic law of entropy has ... caught up with the Soviet system, which now seems to expend more energy on simply maintaining its equilibrium than on improving itself. We could be seeing a period of foreign movement at a time of internal decay". The Soviets were not helped by their aged and sclerotic leadership either: Brezhnev, virtually incapacitated in his last years, was succeeded by Andropov and Chernenko, neither of whom lasted long. After Chernenko's death, Reagan was asked why he had not negotiated with Soviet leaders. Reagan quipped, "They keep dying on me".

End of the Cold War (1985–91)

Main article: Cold War (1985–1991)

Gorbachev reforms

Further information: Mikhail Gorbachev, perestroika, and glasnostBy the time the comparatively youthful Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary in 1985, the Soviet economy was stagnant and faced a sharp fall in foreign currency earnings as a result of the downward slide in oil prices in the 1980s. These issues prompted Gorbachev to investigate measures to revive the ailing state.

An ineffectual start led to the conclusion that deeper structural changes were necessary and in June 1987 Gorbachev announced an agenda of economic reform called perestroika, or restructuring. Perestroika relaxed the production quota system, allowed private ownership of businesses and paved the way for foreign investment. These measures were intended to redirect the country's resources from costly Cold War military commitments to more profitable areas in the civilian sector.

Despite initial scepticism in the West, the new Soviet leader proved to be committed to reversing the Soviet Union's deteriorating economic condition instead of continuing the arms race with the West. Partly as a way to fight off internal opposition from party cliques to his reforms, Gorbachev simultaneously introduced glasnost, or openness, which increased freedom of the press and the transparency of state institutions. Glasnost was intended to reduce the corruption at the top of the Communist Party and moderate the abuse of power in the Central Committee. Glasnost also enabled increased contact between Soviet citizens and the western world, particularly with the United States, contributing to the accelerating détente between the two nations.

Thaw in relations

Further information: Reykjavík Summit, Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, START I, and Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to GermanyIn response to the Kremlin's military and political concessions, Reagan agreed to renew talks on economic issues and the scaling-back of the arms race. The first was held in November 1985 in Geneva, Switzerland. At one stage the two men, accompanied only by a translator, agreed in principle to reduce each country's nuclear arsenal by 50 percent.

A second Reykjavík Summit was held in Iceland. Talks went well until the focus shifted to Reagan's proposed Strategic Defense Initiative, which Gorbachev wanted eliminated: Reagan refused. The negotiations failed, but the third summit in 1987 led to a breakthrough with the signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF). The INF treaty eliminated all nuclear-armed, ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers (300 to 3,400 miles) and their infrastructure.

East–West tensions rapidly subsided through the mid-to-late 1980s, culminating with the final summit in Moscow in 1989, when Gorbachev and George H. W. Bush signed the START I arms control treaty. During the following year it became apparent to the Soviets that oil and gas subsidies, along with the cost of maintaining massive troops levels, represented a substantial economic drain. In addition, the security advantage of a buffer zone was recognised as irrelevant and the Soviets officially declared that they would no longer intervene in the affairs of allied states in Eastern Europe.

In 1989, Soviet forces withdrew from Afghanistan and by 1990 Gorbachev consented to German reunification, the only alternative being a Tiananmen scenario. When the Berlin Wall came down, Gorbachev's "Common European Home" concept began to take shape.

On December 3, 1989, Gorbachev and Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, declared the Cold War over at the Malta Summit; a year later, the two former rivals were partners in the Gulf War against longtime Soviet ally Iraq.

Faltering Soviet system

Further information: Economy of the Soviet Union, Revolutions of 1989, and Baltic WayBy 1989, the Soviet alliance system was on the brink of collapse, and, deprived of Soviet military support, the Communist leaders of the Warsaw Pact states were losing power. In the USSR itself, glasnost weakened the bonds that held the Soviet Union together and by February 1990, with the dissolution of the USSR looming, the Communist Party was forced to surrender its 73-year-old monopoly on state power.

At the same time freedom of press and dissent allowed by glasnost and the festering "nationalities question" increasingly led the Union's component republics to declare their autonomy from Moscow, with the Baltic states withdrawing from the Union entirely. The 1989 revolutionary wave that swept across Central and Eastern Europe overthrew the Soviet-style communist states, such as Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, Romania being the only Eastern-bloc country to topple its communist regime violently and execute its head of state.

Soviet dissolution