| Revision as of 18:00, 2 December 2005 editMetropolitan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,330 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:52, 2 December 2005 edit undoMetropolitan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,330 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

| Second, it is striking how little public consultation was made over such expenditures and tax innovations. Contrary to the lively public debate which accompanied the building of the Métro 70 years previously, the RER aroused little media attention and was essentially decided behind the closed doors of cabinet meetings. The will, and even idealism, of a handful of people — notably Pierre Giraudet, ''Directeur Général'' of the RATP — proved decisive in persuading ministers to grant credits. So too did the united front presented by the RATP and SNCF and their success at keeping within their budgets. Given the subsequent success of the RER, the investment can in retrospect perhaps be considered money well spent. | Second, it is striking how little public consultation was made over such expenditures and tax innovations. Contrary to the lively public debate which accompanied the building of the Métro 70 years previously, the RER aroused little media attention and was essentially decided behind the closed doors of cabinet meetings. The will, and even idealism, of a handful of people — notably Pierre Giraudet, ''Directeur Général'' of the RATP — proved decisive in persuading ministers to grant credits. So too did the united front presented by the RATP and SNCF and their success at keeping within their budgets. Given the subsequent success of the RER, the investment can in retrospect perhaps be considered money well spent. | ||

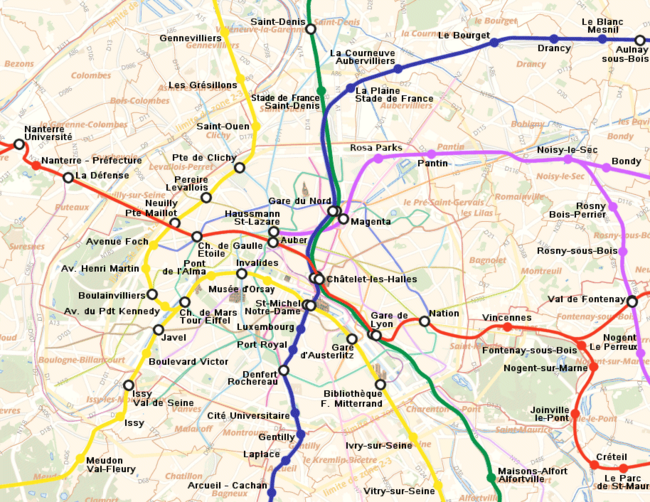

| ==Map== | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Trains== | ==Trains== | ||

Revision as of 23:52, 2 December 2005

- This page is about the Paris rail network. In biology, RER is the abbreviation for rough endoplasmic reticulum.

| Paris RER network | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

The RER (Réseau Express Régional, IPA /εr ə εr/, "Regional Express Network") is an urban rail network in Paris and the surrounding Île-de-France region of France.

The RER is a hybrid transportation system being half way between suburban rail and subway. RER lines are pre-existing suburban lines connected to one another through long modern tunnels crossing the center of Paris. Within the city of Paris, they serve as express lines offering multiple connections to the Paris Métro. The essential central part of the network was completed by a massive civil engineering effort between 1962 and 1977, and features some unusually deep and spacious stations. The RER network is still expanding today — the new line E was inaugurated in 1999. As of 2005 the RER comprises five lines: A, B, C, D and E.

Due to its hybrid aspect, being both a subway network and a suburban network, some parts of RER lines are operated by the city transport authority managing the métro (RATP) and others by the national rail company (SNCF).

History

Origins

The origins of the RER can be traced back to the 1936 Ruhlmann-Langewin plan of the Compagnie du Métropolitain de Paris for a wide-sectioned "métropolitain express" (express metro). As the CMP's post-war successor, the RATP revived the scheme in the 1950s, with the result that that an interministerial committee decided in 1960 to go ahead with construction of a first, east-west, line. As its chief inspiration, the RATP was granted authority to run the new link and the SNCF thus ceded operation of the Saint-Germain-en-Laye line (to the west of Paris) and the Vincennes line (to the east). The embryonic (and as yet unnamed) RER was conceived in the 1965 Schéma directeur d'aménagement et d'urbanisme as an "H"-shaped rapid transit network (that is, with two north-south routes). Only a single north-south axis crossing the Left Bank came to fruition, although the Métro's Line 13 was upgraded to perform a similar function.

Pioneering

In the first phase of construction the Saint-Germain and Vincennes lines became the ends of the east-west Line A, whose central section was opened station by station between 1969 and 1977. On its completion the Line A was joined by an initial southern leg of the north-south Line B. During this first phase six new stations were built, three entirely underground and all on a grand scale.

Construction was ceremonially inaugurated by Robert Buron, Minister for Public Works, on 6 July 1961. The rapid expansion of the La Défense business district in the west made the western section of the new east-west route a priority and it was here that tunnelling began properly in 1962. Such was the scale of the work that it was not until 12 December 1969 that the first new station — and the RER name — were inaugurated, at Nation on the eastern section. Nation became the new terminus of the Vincennes line from Boissy. A few weeks later came the long-awaited opening of the western line from Étoile (not yet renamed after Charles de Gaulle) to La Défense. A simple shuttle service, this western section was extended eastward to the newly-built, central Auber station on 23 November 1971, and westward on 1 October 1972 to Saint-Germain-en-Laye by means of connection to the Saint-Germain-en-Laye line (the oldest railway line in France) at Nanterre - Préfecture.

The RER network truly came into being on December 9 1977 with the joining of the Nation-Boissy and Auber-Saint-Germain-en-Laye segments as the eastern and western halves of the RER Line A at the just-completed hub station of Châtelet - Les Halles in the heart of Paris. The southern Ligne de Sceaux was simultaneously extended from its terminus at Luxembourg to meet Line A at Châtelet – Les Halles, becoming the new Line B. The system of line letters was introduced to the public on this occasion, though it had been used internally at RATP and SNCF for some time already.

Completion

A second phase, from the end of the 1970s, was of more soberly paced completion. The SNCF gained the right to operate its own routes outright, which were to become lines C, D and E. Extensive sections of suburban track were added to the network but only four new stations were built. Of these, two were comparable in audaciousness to those of the 1970s. The network as it is today was completed in the following stages:

- Line C (following the Left Bank of the Seine) was added in 1979, involving the construction of a short cut-and-cover link between Invalides and Musée d'Orsay.

- Line B extension to the Gare du Nord and the north was effected in 1983, by means of a new deep tunnel from Châtelet - Les Halles.

- Line D (north to south-east, via Châtelet – Les Halles) was added in 1995, using a new deep tunnel between Châtelet – Les Halles and Gare de Lyon. No new building work was necessary at Châtelet – Les Halles, since — in an example of superb planning, additional platforms for an eventual Line D had been built at the time of the station's construction 20 years earlier.

- Line E was added in 1998, connecting the north-east with Gare Saint-Lazare by means of a new deep tunnel from Gare de l'Est.

Enduring investment

Two aspects of the RER's pioneering phase in the 1960s and 1970s are particularly noteworthy. The first is the spectacular scale and expense of the enterprise. For example, FF 2 billion were committed to the project in the budget of 1973 alone. This equates to roughly EUR 1.3 billion in 2005 terms, and closer to double that when stated as a proportion of the region's (then much smaller) economic output (Gerondeau C, 2003). This and subsequent spending is partly explained by the regional versement transport ("transport contribution"), a small levy made on businesses that evidently benefit from the vast labour market put at their disposal by the RER. This peculiarly French invention was passed by a law in June 1971 and has been a permanent source of revenue for transport investment ever since.

Second, it is striking how little public consultation was made over such expenditures and tax innovations. Contrary to the lively public debate which accompanied the building of the Métro 70 years previously, the RER aroused little media attention and was essentially decided behind the closed doors of cabinet meetings. The will, and even idealism, of a handful of people — notably Pierre Giraudet, Directeur Général of the RATP — proved decisive in persuading ministers to grant credits. So too did the united front presented by the RATP and SNCF and their success at keeping within their budgets. Given the subsequent success of the RER, the investment can in retrospect perhaps be considered money well spent.

Map

Trains

The overall predominance of suburban SNCF track on the RER network explains why RER trains drive on the left, like SNCF trains (except in Alsace-Moselle), and contrary to the Métro where trains drive on the right. RER trains run by the two different operators share the same track infrastructure, a practice called interconnection. On the RER, interconnection required the development of specific trains (MI79 series for Materiel d'Interconnexion 1979, and MI2N series for Materiel d'Interconnexion à 2 niveaux (two-level interconnection stock)) capable of operating under both the 1.5 kV direct current on the RATP network and the 25 kV / 50 Hz alternating current on the SNCF network. The MS61 series (for Matériel Simple 1961) can be used only on the 1.5 kV DC network.

The RER's tunnels have unusually large cross-sections. This is due to a 1961 decision to build according to a standard set by the Union Internationale des Chemins de Fer, with space for overheard catenary power supply to trains. Single-track tunnels thus measure 6.30 m across and double-track tunnels up to 8.70 m - meaning a cross-sectional area of up to 50 square metres, larger than that of the stations on many comparable underground rail networks.

Stations

The six stations of Line A opened between 1969 and 1977, and built under the heart of Paris, are:

- La Défense (situated beneath the current site of the Grande Arche de la Défense, just outside the Paris perimeter)

- Charles de Gaulle - Étoile (entirely underground construction at the site of the Arc de Triomphe)

- Auber (entirely underground and once the largest underground station in the world, situated near Gare Saint-Lazare)

- Châtelet - Les Halles (built on the site of the former marketplace and today perhaps the largest underground station in Europe)

- Gare de Lyon (platforms built directly beneath and alongside the mainline SNCF station)

- Nation (entirely underground construction at the Place de la Nation)

Some controversy followed the construction of the Line A. Using the model of the existing Métro, and unlike any other underground network in the world, engineers elected to build the three new deep stations (Étoile, Auber and Nation) in the configuration of single monolithic halls with lateral platforms and no supporting pillars. A hybrid solution of adjacently-positioned halls was rejected on the grounds that it "completely sacrificed the architectural aspect" of the oeuvre (Gerondeau 2003, p31). Yet the scale in question was vast: the new stations cathédrales were to be up to three times longer, wider and taller than Métro stations, and hence 20 or 30 times more voluminous. Most importantly, unlike the Métro they were to be constructed entirely underground. The decision turned out to be expensive - around FFr1.2 billion for the three stations, equivalent to €1.2 billion in 2005 terms, with the two-level Auber the costliest of the three. The comparison was obvious and unfavourable with London's Victoria Line, a deep line of 22 km constructed during the same period using a two-tunnel approach at vastly lower cost. However, the three stations represent undeniable engineering feats and are noticeably less claustrophobic than traditional underground stations.

Since Lines C and D used essentially pre-existing infrastructure (with the detailed exceptions), only four new stations have been inaugurated since 1979:

- Gare du Nord (dedicated RER platforms on two levels, opened 1982)

- St-Michel - Nôtre-Dame (1988), opened on an existing stretch of the Line B between Luxembourg and Châtelet - Les Halles and remarkable for its two-tunnel architecture, common to many other deep underground systems but unique in Paris

- Magenta (serving both Gare du Nord and Gare de l'Est) and Haussmann - St-Lazare (both 1998). The two new stations of the Line E are notable for the lavish spaciousness of their entirely underground construction. In this way they are similar to the 1960s "cathedral stations" of the Line A (see above), though their passenger traffic has proved vastly lower.

Lines

| Line Name | Map Colour | Opened | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Line A | Red | 1977 | 109 km / 67 miles |

| Line B | Blue | 1977 | 80 km / 50 miles |

| Line C | Yellow | 1979 | 186 km / 115 miles |

| Line D | Green | 1987 | 145 km / 90 miles |

| Line E | Purple | 1999 | 32 km / 20 miles |

Future developments

The main hypotheses for future extensions to the RER focus on the Line E, which currently ends at Haussmann - St-Lazare.

Various Line E extensions have been proposed:

- Eastwards from Chelles-Gournay to Esbly and Meaux

- Eastwards from Tournon to Coulommiers

- Westwards from Haussmann - St Lazare to Saint-Nom-la-Bretèche and Versailles Rive-Droite, via a new station at Champs-Elysées - Clémenceau and Gare Montparnasse.

A new Line E station has also been proposed at Rue de l'Évangile on the existing approach to Gare de l'Est, with a tentative opening date of 2010.

Plans exist for a line F, which would connect Argenteuil to Rambouillet via the existing tracks of the St-Lazare and Montparnasse rail networks. A new tunnel would be bored below Paris, with the creation of a station at Invalides. At present, this is not foreseen before 2020.

International comparison

The abbreviation RER is commonly used to describe the urban rail network currently being planned for the Brussels region and for major cities in Switzerland. German equivalents of the RER are known as the S-Bahn.

See also

- List of stations of the Paris RER for a complete list of stations

- Transportation in France.

References

- Gaillard, M. (1991). Du Madeleine-Bastille à Météor: Histoire des transports Parisiens, Amiens: Martelle. ISBN 2878900138. (French)

- Gerondeau, C. (2003). La Saga du RER et le maillon manquant, Paris: Presse de l'École nationale des ponts et chaussées. ISBN 2-85978-368-7. (French)