| Revision as of 19:32, 22 May 2005 view sourceCortonin (talk | contribs)1,678 edits RV plus add reference to the literature.← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:36, 22 May 2005 view source William M. Connolley (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers66,036 edits Rv, as everNext edit → | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

| The result of the greenhouse effect is that average surface temperatures are considerably higher than they would otherwise be if the earth's surface temperature were determined solely by the ] and blackbody properties of the surface. | The result of the greenhouse effect is that average surface temperatures are considerably higher than they would otherwise be if the earth's surface temperature were determined solely by the ] and blackbody properties of the surface. | ||

| It is commonplace for simplistic descriptions of the "greenhouse" effect to assert that the same mechanism warms greenhouses (e.g. ), but this is an incorrect oversimplification: see below. | |||

| === Limiting factors === | === Limiting factors === | ||

| The degree of the greenhouse effect is dependent primarily on the concentration of ]es in the planetary atmosphere. The ]-rich atmosphere of ] causes a ''runaway greenhouse effect'' with surface temperatures hot enough to melt ], the atmosphere of ] creates habitable temperatures, and the thin atmosphere of ] causes a minimal greenhouse effect. | The degree of the greenhouse effect is dependent primarily on the concentration of ]es in the planetary atmosphere. The ]-rich atmosphere of ] causes a ''runaway greenhouse effect'' with surface temperatures hot enough to melt ], the atmosphere of ] creates habitable temperatures, and the thin atmosphere of ] causes a minimal greenhouse effect. | ||

| The use of the term ''runaway'' greenhouse effect to describe the effect as it occurs on Venus emphasises the interaction of the greenhouse effect with other processes in ]. Venus is sufficiently strongly heated by the Sun that ] is vaporised and so ] is not reabsorbed by the planetary crust. As a result, the greenhouse effect has been progressively intensified by positive feedback. On Earth there is a substantial ] and ] which respond to higher temperatures by recycling atmospheric ] more quickly (in geologic terms; the timescale for the ocean/biosphere to remove a CO<sub>2</sub> perturbation is on the order of several hundred years). The presence of liquid water thus limits the increase in the greenhouse effect through negative feedback. This state of affairs is expected to persist for at least hundreds of millions of years, but, ultimately, the ] will overwhelm this regulatory effect. | The use of the term ''runaway'' greenhouse effect to describe the effect as it occurs on Venus emphasises the interaction of the greenhouse effect with other processes in ]. Venus is sufficiently strongly heated by the Sun that ] is vaporised and so ] is not reabsorbed by the planetary crust. As a result, the greenhouse effect has been progressively intensified by positive feedback. On Earth there is a substantial ] and ] which respond to higher temperatures by recycling atmospheric ] more quickly (in geologic terms; the timescale for the ocean/biosphere to remove a CO<sub>2</sub> perturbation is on the order of several hundred years). The presence of liquid water thus limits the increase in the greenhouse effect through negative feedback. This state of affairs is expected to persist for at least hundreds of millions of years, but, ultimately, the ] will overwhelm this regulatory effect. | ||

| The average surface temperature would be -18°C without a greenhouse effect or 72°C with just the greenhouse effect and no convection, but in reality this temperature is closer to 15°C due to convective flow of heat energy within the atmosphere and partly above much of the thermal IR absorbence of the atmosphere. |

The average surface temperature would be -18°C without a greenhouse effect or 72°C with just the greenhouse effect and no convection, but in reality this temperature is closer to 15°C due to convective flow of heat energy within the atmosphere and partly above much of the thermal IR absorbence of the atmosphere. | ||

| === The greenhouse gases === | === The greenhouse gases === | ||

| ] (H<SUB>2</SUB>O) causes about 60% of Earth's naturally-occurring greenhouse effect. Other gases influencing the effect include ] (CO<SUB>2</SUB>) (about 26%), ] (CH<SUB>4</SUB>), ] (N<SUB>2</SUB>O) and ] (O<SUB>3</SUB>) (about 8%) . Collectively, these gases are known as ]es. | ] (H<SUB>2</SUB>O) causes about 60% of Earth's naturally-occurring greenhouse effect. Other gases influencing the effect include ] (CO<SUB>2</SUB>) (about 26%), ] (CH<SUB>4</SUB>), ] (N<SUB>2</SUB>O) and ] (O<SUB>3</SUB>) (about 8%) . Collectively, these gases are known as ]es. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 49: | ||

| == Effects of various gases == | == Effects of various gases == | ||

| It is hard to disentangle the percentage contributions to the greenhouse effect by different gases, because their respective infrared spectrums overlap. However, one can calculate the percentage of trapped radiation remaining, and discover: | It is hard to disentangle the percentage contributions to the greenhouse effect by different gases, because their respective infrared spectrums overlap. However, one can calculate the percentage of trapped radiation remaining, and discover: | ||

| <center> | <center> | ||

| Line 78: | Line 83: | ||

| Including clouds, the table above would suggest 50%. For the cloudless case, ] 1990, p 47-48 estimate water vapor at 60-70% whereas Baliunas & Soon estimate 88% considering only H<sub>2</sub>O and CO<sub>2</sub>. | Including clouds, the table above would suggest 50%. For the cloudless case, ] 1990, p 47-48 estimate water vapor at 60-70% whereas Baliunas & Soon estimate 88% considering only H<sub>2</sub>O and CO<sub>2</sub>. | ||

| ⚫ | Water vapor in the ], unlike the better-known greenhouse gases such as CO<sub>2</sub>, is essentially passive in terms of climate: the residence time for water vapor in the atmosphere is short (about a week) so perturbations to water vapor rapidly re-equilibriate. In contrast, the lifetimes of CO<sub>2</sub>, methane, etc, are long (hundreds of years) and hence perturbations remain. Thus, in response to a temperature perturbation caused by enhanced CO<sub>2</sub>, water vapor would increase, resulting in a (limited) positive feedback and higher temperatures. In response to a perturbation from enhanced water vapor, the atmosphere would re-equilibriate due to clouds causing reflective cooling and water-removing rain. The ]s of high-flying ] sometimes form high clouds which seem to slightly alter the local weather. | ||

| RealClimate estimated that water vapor contributes between 36-66% in the cloudless case, or 66-85% if clouds are included. The lower bounds of these estimates are the amount of change if water vapor and clouds are removed, and the upper bounds are the remaining greenhouse effect if everything but water vapor and clouds are removed. | |||

| ⚫ | Water vapor in the ], unlike |

||

| == Global warming == | == Global warming == | ||

| In recent years researchers see the increasing greenhouse effect from increasing CO2 and other gases as a significant contributing factor to the current ]. | In recent years researchers see the increasing greenhouse effect from increasing CO2 and other gases as a significant contributing factor to the current ]. | ||

| See ] and ] for more. | See ] and ] for more. | ||

| == Origin of the term and real greenhouses == | |||

| == Real greenhouses == | |||

| The term 'greenhouse effect' originally came from the greenhouses used for gardening. The global greenhouse effect experiences a similar thermal infrared absorption effect to what occurs with the ] of a gardening ] (Joliet, et al., 1991). The gardening greenhouse is reasonably well isolated from direct convection with the atmosphere and this ''isolation'' means that the warmed air is not free to convect out of the greenhouse. In the free atmosphere convection does play a significant role in global atmospheric heat redistribution. In the absence of atmospheric convection, average surface temperatures would be 72°C, rather than the current temperature 15°C, which is actually closer to the blackbody temperature of the Earth, -18°C, which would occur in the absence of any global greenhouse effect. This difference in temperatures is because convection facilitates redistribution of heat energy, sometimes raising hot air above much of the greenhouse gases in the same way that convection through a window of a greenhouse would move heat energy outside of the greenhouse. | |||

| The term 'greenhouse effect' originally came from the greenhouses used for gardening, but it is a misnomer since greenhouses operate differently (Fleagle and Businger, 1980; Idso, 1982; Henderson-Sellers and McGuffie). A greenhouse is built of glass; it heats up primarily because the Sun warms the ground inside it, which warms the air near the ground, and this air is prevented from rising and flowing away. The warming inside a greenhouse thus occurs by suppressing convection and turbulent mixing. This can be demonstrated by opening a small window near the roof of a greenhouse: the temperature will drop considerably. It has also been demonstrated experimentally (Wood, 1909): a "greenhouse" built of rock salt (which is transparent to IR) heats up just as one built of glass does. Greenhouses thus work primarily by preventing '']''; the greenhouse effect however reduces ''radiation loss'', not convection. It is quite common, however, to find sources (e.g. | |||

| Energy is redistributed by convection in the global greenhouse effect past the IR absorbent barrier, but very little of the energy trapped by a gardening greenhouse is able to convect past the barrier. This difference is one reason that the term ''greenhouse effect'' is sometimes called a misnomer when applied to the global system. | |||

| ) that make the "greenhouse" analogy. Although the primary mechanism for warming greenhouses is the prevention of mixing with the free atmosphere, the radiative properties of the glazing can still be important to commercial growers. With the modern development of new plastic surfaces and glazings for greenhouses, this has permitted construction of greenhouses which selectively control radiation transmittance in order to better control the growing environment.. | |||

| {{seemain|Solar greenhouse (technical)}} | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 110: | Line 112: | ||

| * Henderson-Sellers, A and McGuffie, K: A climate modelling primer (quote: ''Greenhouse effect: the effect of the atmosphere in re-readiating longwave radiation back to the surface of the Earth. It has nothing to do with glasshouses, which trap warm air at the surface''). | * Henderson-Sellers, A and McGuffie, K: A climate modelling primer (quote: ''Greenhouse effect: the effect of the atmosphere in re-readiating longwave radiation back to the surface of the Earth. It has nothing to do with glasshouses, which trap warm air at the surface''). | ||

| * Idso, S.B.: Carbon Dioxide: friend or foe, 1982 (quote: ''...the phraseology is somewhat in appropriate, since CO2 does not warm the planet in a manner analogous to the way in which a greenhouse keeps its interior warm''). | * Idso, S.B.: Carbon Dioxide: friend or foe, 1982 (quote: ''...the phraseology is somewhat in appropriate, since CO2 does not warm the planet in a manner analogous to the way in which a greenhouse keeps its interior warm''). | ||

| * Joliet O., et al.; ''Horticern - An Improved Static Model for Predicting the Energy-Consumption of a Greenhouse'', Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 55(3-4): 265-294 Jun 1991, ''A detailed explanation of the gardening greenhouse mechanism.'' | |||

| * Kiehl, J.T., and Trenberth, K. (1997). Earth's annual mean global energy budget, ''Bulletin of the ]'' '''78''' (2), 197–208. | * Kiehl, J.T., and Trenberth, K. (1997). Earth's annual mean global energy budget, ''Bulletin of the ]'' '''78''' (2), 197–208. | ||

| * Piexoto, JP and Oort, AH: Physics of Climate, American Institute of Physics, 1992 (quote: ''...the name water vapor-greenhouse effect is actually a misnomer since heating in the usual greenhouse is due to the reduction of convection'') | * Piexoto, JP and Oort, AH: Physics of Climate, American Institute of Physics, 1992 (quote: ''...the name water vapor-greenhouse effect is actually a misnomer since heating in the usual greenhouse is due to the reduction of convection'') | ||

| Line 119: | Line 120: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 19:36, 22 May 2005

The greenhouse effect, first discovered by Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier in 1824, is the process by which an atmosphere warms a planet.

Mars, Venus and other celestial bodies with atmospheres (such as Titan) have greenhouse effects, but for simplicity the rest of this article will refer to the case of Earth.

The term greenhouse effect may be used to refer to two different things in common parlance: the natural greenhouse effect, which refers to the greenhouse effect which occurs naturally on earth, and the enhanced (anthropogenic) greenhouse effect, which results from human activities (see also global warming). The former is accepted by all; the latter is accepted by most scientists, although there is some dispute.

The natural greenhouse effect

Process

The earth receives an enormous amount of solar radiation. Just above the atmosphere, the solar power flux density averages about 1367 watts/m, or 1.28 * 10 watts over the entire earth. This figure vastly exceeds the power generated by human activities.

The solar power hitting earth is balanced over time by a roughly equal amount of power radiating from the earth (as the amount of energy from the sun that is stored is small). Almost all radiation leaving the earth takes two forms: reflected solar radiation and thermal blackbody radiation.

Reflected solar radiation accounts for 30% of the earth's total radiation: on average, 6% of the incoming solar radiation is reflected by the atmosphere, 20% is reflected by clouds, and 4% is reflected by the surface.

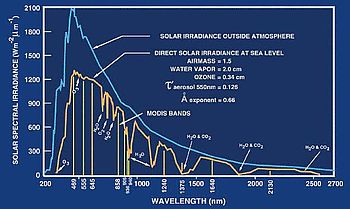

The remaining 70% of the incoming solar radiation is absorbed: 16% by the atmosphere (including the almost complete absorption of shortwave ultraviolet over most areas by the stratospheric ozone layer); 3% by clouds; and 51% by the land and oceans. This absorbed energy heats the atmosphere, oceans, land and powers life on the planet.

Like the sun, the earth is a thermal blackbody radiator. So because the earth's surface is much cooler than the sun (287 K vs 5780 K), Wien's displacement law dictates that the earth must radiate its thermal energy at much longer wavelengths than the sun. While the sun's radiation peaks at a visible wavelength of 500 nanometers, earth's radiation peak is in the longwave (far) infrared at about 10 micrometres.

The earth's atmosphere is largely transparent at visible and near-infrared wavelengths, but not at 10 micrometres. Only about 6% of the earth's total radiation to space is direct thermal radiation from the surface. The atmosphere absorbs 71% of the surface thermal radiation before it can escape. The atmosphere itself behaves as a blackbody radiator in the far infrared, so it re-radiates this energy.

The earth's atmosphere and clouds therefore account for 91.4% of its longwave infrared radiation and 64% of the earth's total emissions at all wavelengths. The atmosphere and clouds get this energy from the solar energy they directly absorb; thermal radiation from the surface; and from heat brought up by convection and the condensation of water vapor.

Because the atmosphere is such a good absorber of longwave infrared, it effectively forms a one-way blanket over the earth's surface. Visible and near-visible radiation from the sun easily gets through, but thermal radiation from the surface can't easily get back out. In response, the earth's surface warms up. The power of the surface radiation increases by the Stefan-Boltzmann law until it (over time) compensates for the atmospheric absorption.

The surface of the Earth is in constant flux with daily, yearly, and ages long cycles and trends in temperature and other variables from a variety of causes.

The result of the greenhouse effect is that average surface temperatures are considerably higher than they would otherwise be if the earth's surface temperature were determined solely by the albedo and blackbody properties of the surface.

It is commonplace for simplistic descriptions of the "greenhouse" effect to assert that the same mechanism warms greenhouses (e.g. ), but this is an incorrect oversimplification: see below.

Limiting factors

The degree of the greenhouse effect is dependent primarily on the concentration of greenhouse gases in the planetary atmosphere. The carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere of Venus causes a runaway greenhouse effect with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead, the atmosphere of Earth creates habitable temperatures, and the thin atmosphere of Mars causes a minimal greenhouse effect.

The use of the term runaway greenhouse effect to describe the effect as it occurs on Venus emphasises the interaction of the greenhouse effect with other processes in feedback cycles. Venus is sufficiently strongly heated by the Sun that water is vaporised and so carbon dioxide is not reabsorbed by the planetary crust. As a result, the greenhouse effect has been progressively intensified by positive feedback. On Earth there is a substantial hydrosphere and biosphere which respond to higher temperatures by recycling atmospheric carbon more quickly (in geologic terms; the timescale for the ocean/biosphere to remove a CO2 perturbation is on the order of several hundred years). The presence of liquid water thus limits the increase in the greenhouse effect through negative feedback. This state of affairs is expected to persist for at least hundreds of millions of years, but, ultimately, the warming of an aging Sun will overwhelm this regulatory effect.

The average surface temperature would be -18°C without a greenhouse effect or 72°C with just the greenhouse effect and no convection, but in reality this temperature is closer to 15°C due to convective flow of heat energy within the atmosphere and partly above much of the thermal IR absorbence of the atmosphere.

The greenhouse gases

Water vapor (H2O) causes about 60% of Earth's naturally-occurring greenhouse effect. Other gases influencing the effect include carbon dioxide (CO2) (about 26%), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and ozone (O3) (about 8%) . Collectively, these gases are known as greenhouse gases.

The wavelengths of light that a gas absorbs can be modelled with quantum mechanics based on molecular properties of the different gas molecules. It so happens that heteronuclear diatomic molecules and tri- (and more) atomic gases absorb at infrared wavelengths but homonuclear diatomic molecules do not absorb infrared light. This is why H2O and CO2 are greenhouse gases but the major atmospheric constituents (N2 and O2) are not.

Between the absorptions of water vapor and those of carbon dioxide, there is an atmospheric window where, prior to the industrial era, no infrared radiation was trapped, lying between 8 and 15 micrometres. Compounds such as perflurocarbons (CF4, C2F6 etc.), chlorofluorocarbons, halons and SF6 absorb very strongly in this window. This means that they are extremely potent greenhouse gases, especially given the absence of natural sinks to remove them. Perfluorocarbons can have a lifetime of 50,000 years, possibly longer.

Effects of various gases

It is hard to disentangle the percentage contributions to the greenhouse effect by different gases, because their respective infrared spectrums overlap. However, one can calculate the percentage of trapped radiation remaining, and discover:

| Species removed |

% trapped radiation remaining |

|---|---|

| All | 0 |

| H2O, CO2, O3 | 50 |

| H2O | 64 |

| Clouds | 86 |

| CO2 | 88 |

| O3 | 97 |

| None | 100 |

(Source: Ramanathan and Coakley, Rev. Geophys and Space Phys., 16 465 (1978))

Water vapor effects

Water vapor is the major contributor to Earth's greenhouse effect. Its effects vary due to localized concentrations, mixture with other gases, frequencies of light, different behavior in different levels of the atmosphere, and whether positive or negative feedback takes place. High humidity also affects cloud formation, which has major effects upon temperature but is distinct from water vapor gas.

The IPCC TAR (2001; section 2.5.3) reports that, despite non-uniform effects and difficulties in assessing the quality of the data, water vapor has generally increased over the 20th Century.

Estimates of the percentage of Earth's greenhouse effect due to water vapor:

Including clouds, the table above would suggest 50%. For the cloudless case, IPCC 1990, p 47-48 estimate water vapor at 60-70% whereas Baliunas & Soon estimate 88% considering only H2O and CO2. Water vapor in the troposphere, unlike the better-known greenhouse gases such as CO2, is essentially passive in terms of climate: the residence time for water vapor in the atmosphere is short (about a week) so perturbations to water vapor rapidly re-equilibriate. In contrast, the lifetimes of CO2, methane, etc, are long (hundreds of years) and hence perturbations remain. Thus, in response to a temperature perturbation caused by enhanced CO2, water vapor would increase, resulting in a (limited) positive feedback and higher temperatures. In response to a perturbation from enhanced water vapor, the atmosphere would re-equilibriate due to clouds causing reflective cooling and water-removing rain. The contrails of high-flying aircraft sometimes form high clouds which seem to slightly alter the local weather.

Global warming

In recent years researchers see the increasing greenhouse effect from increasing CO2 and other gases as a significant contributing factor to the current global warming.

See Global warming and Attribution of recent climate change for more.

Real greenhouses

The term 'greenhouse effect' originally came from the greenhouses used for gardening, but it is a misnomer since greenhouses operate differently (Fleagle and Businger, 1980; Idso, 1982; Henderson-Sellers and McGuffie). A greenhouse is built of glass; it heats up primarily because the Sun warms the ground inside it, which warms the air near the ground, and this air is prevented from rising and flowing away. The warming inside a greenhouse thus occurs by suppressing convection and turbulent mixing. This can be demonstrated by opening a small window near the roof of a greenhouse: the temperature will drop considerably. It has also been demonstrated experimentally (Wood, 1909): a "greenhouse" built of rock salt (which is transparent to IR) heats up just as one built of glass does. Greenhouses thus work primarily by preventing convection; the greenhouse effect however reduces radiation loss, not convection. It is quite common, however, to find sources (e.g. ) that make the "greenhouse" analogy. Although the primary mechanism for warming greenhouses is the prevention of mixing with the free atmosphere, the radiative properties of the glazing can still be important to commercial growers. With the modern development of new plastic surfaces and glazings for greenhouses, this has permitted construction of greenhouses which selectively control radiation transmittance in order to better control the growing environment..

See also

References

- Earth Radiation Budget, http://marine.rutgers.edu/mrs/education/class/yuri/erb.html

- Fleagle, RG and Businger, JA: An introduction to atmospheric physics, 2nd edition, 1980

- Fraser, Alistair B., Bad Greenhouse http://www.ems.psu.edu/~fraser/Bad/BadGreenhouse.html

- Giacomelli, Gene A. and William J. Roberts1, Greenhouse Covering Systems, Rutgers University, downloaded from: http://ag.arizona.edu/ceac/research/archive/HortGlazing.pdf on 3-30-2005.

- Henderson-Sellers, A and McGuffie, K: A climate modelling primer (quote: Greenhouse effect: the effect of the atmosphere in re-readiating longwave radiation back to the surface of the Earth. It has nothing to do with glasshouses, which trap warm air at the surface).

- Idso, S.B.: Carbon Dioxide: friend or foe, 1982 (quote: ...the phraseology is somewhat in appropriate, since CO2 does not warm the planet in a manner analogous to the way in which a greenhouse keeps its interior warm).

- Kiehl, J.T., and Trenberth, K. (1997). Earth's annual mean global energy budget, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78 (2), 197–208.

- Piexoto, JP and Oort, AH: Physics of Climate, American Institute of Physics, 1992 (quote: ...the name water vapor-greenhouse effect is actually a misnomer since heating in the usual greenhouse is due to the reduction of convection)

- Wood, R.W. (1909). Note on the Theory of the Greenhouse, Philosophical Magazine 17, p319–320. For the text of this online, see http://www.wmconnolley.org.uk/sci/wood_rw.1909.html