| Revision as of 22:52, 8 July 2023 editDraken Bowser (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,704 editsm sing.Tag: 2017 wikitext editor← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:27, 9 July 2023 edit undoHawkeye7 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors124,453 edits Changes per GA reviewTag: harv-errorNext edit → | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| In 1939, a team of scientists at the ] at the ], led by ] that included ], ], ] and ], began researching penicillin. They developed a method for cultivating the mould and extracting, purifying and storing penicillin from it, together with an ] for measuring its purity. They carried out experiments with animals to determine penicillin's safety and effectiveness before conducting clinical trials and field tests. They derived its chemical formula and determined how it works. The private sector and the ] located and produced new strains and developed mass production techniques. Fleming, Florey and Chain shared the 1945 ] for the discovery and development of penicillin. | In 1939, a team of scientists at the ] at the ], led by ] that included ], ], ] and ], began researching penicillin. They developed a method for cultivating the mould and extracting, purifying and storing penicillin from it, together with an ] for measuring its purity. They carried out experiments with animals to determine penicillin's safety and effectiveness before conducting clinical trials and field tests. They derived its chemical formula and determined how it works. The private sector and the ] located and produced new strains and developed mass production techniques. Fleming, Florey and Chain shared the 1945 ] for the discovery and development of penicillin. | ||

| After the end of the ] in 1945, |

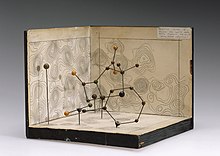

After the end of the ] in 1945, ] penicillins were produced. The drug was synthesised in 1957, but cultivation of mould remains the primary means of production. ] received the 1964 ] for determining the structures of important biochemical substances including penicillin. It was discovered that adding penicillin to animal feed increased weight gain, improved feed-conversion efficiency, promoted more uniform growth and facilitated disease control. Agriculture became a major user of penicillin. Shortly after their discovery of penicillin, the Oxford team reported penicillin resistance in many bacteria. Research that aims to circumvent and understand the mechanisms of ] continues today. | ||

| ==Early evidence== | ==Early evidence== | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| {{anchor|Early scientific evidence}}In 1871, Sir ] reported that ] fluid covered with mould would produce no ]l growth.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Burdon-Sanderson |first=J. S. |title=Memoirs: The Origin and Distribution of Microzymes (Bacteria) in Water, and the Circumstances which determine their Existence in the Tissues and Liquids of the Living Body |journal=Journal of Cell Science |date=1 October 1871 |volume=11 |issue=44 |pages=323–352 |doi=10.1242/jcs.s2-11.44.323 |doi-broken-date=7 July 2023 |url=https://journals.biologists.com/jcs/article-abstract/s2-11/44/323/61491/Memoirs-The-Origin-and-Distribution-of-Microzymes |access-date=8 July 2023 }}</ref> ], an English surgeon and the father of modern ], observed in November 1871 that urine samples contaminated with mould also did not permit the growth of bacteria. He also described the antibacterial action on human tissue of a species of mould he called '']'' but did not publish his results.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=13–15}} In 1875 ] demonstrated to the ] the antibacterial action of the ''Penicillium'' fungus.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www1.umn.edu/ships/updates/fleming.htm |publisher=SHiPS Resource Center |title=Penicillin & Chance | first = Douglas | last = Allchin |access-date=2010-02-09 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090528100504/http://www1.umn.edu/ships/updates/fleming.htm |archive-date=28 May 2009 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> | {{anchor|Early scientific evidence}}In 1871, Sir ] reported that ] fluid covered with mould would produce no ]l growth.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Burdon-Sanderson |first=J. S. |title=Memoirs: The Origin and Distribution of Microzymes (Bacteria) in Water, and the Circumstances which determine their Existence in the Tissues and Liquids of the Living Body |journal=Journal of Cell Science |date=1 October 1871 |volume=11 |issue=44 |pages=323–352 |doi=10.1242/jcs.s2-11.44.323 |doi-broken-date=7 July 2023 |url=https://journals.biologists.com/jcs/article-abstract/s2-11/44/323/61491/Memoirs-The-Origin-and-Distribution-of-Microzymes |access-date=8 July 2023 }}</ref> ], an English surgeon and the father of modern ], observed in November 1871 that urine samples contaminated with mould also did not permit the growth of bacteria. He also described the antibacterial action on human tissue of a species of mould he called '']'' but did not publish his results.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=13–15}} In 1875 ] demonstrated to the ] the antibacterial action of the ''Penicillium'' fungus.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www1.umn.edu/ships/updates/fleming.htm |publisher=SHiPS Resource Center |title=Penicillin & Chance | first = Douglas | last = Allchin |access-date=2010-02-09 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090528100504/http://www1.umn.edu/ships/updates/fleming.htm |archive-date=28 May 2009 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> | ||

| In 1876, German biologist ] discovered that a bacterium ('']'') was the causative pathogen of ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Koch |first=Robert |date=2010 |orig-year=1876 |others=Robert Koch-Institut |title=Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis|trans-title=The Etiology of Anthrax Disease, Based on the Developmental History of Bacillus Anthracis |url=https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/5139|journal=Cohns Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen |issn=0005-8041 |language=de |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=277 (1–22)|doi=10.25646/5064}}</ref> which became the first demonstration that a specific bacterium caused a specific disease and the first direct evidence of ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lakhtakia|first=Ritu|date=2014|title=The Legacy of Robert Koch: Surmise, search, substantiate|journal=Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=e37–41 |doi=10.12816/0003334 |pmc=3916274 |pmid=24516751}}</ref> In 1877, French biologists ] and Jules Francois Joubert observed that cultures of anthrax bacilli, when contaminated with moulds, could be successfully inhibited.<ref name=":14">{{cite journal|last=Shama |first=G. |date=September 2016|title=La Moisissure et la Bactérie: Deconstructing the fable of the discovery of penicillin by Ernest Duchesne|url=https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/21810|journal=Endeavour|issn=0160-9327|volume=40|issue=3|pages=188–200|doi=10.1016/j.endeavour.2016.07.005|pmid=27496372}}</ref> Reporting in the ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences'', they concluded:{{blockquote|Neutral or slightly alkaline urine is an excellent medium for the bacteria. If the urine is sterile and the culture pure the bacteria multiply so fast that in the course of a few hours their filaments fill the fluid with a downy felt. But if when the urine is inoculated with these bacteria an aerobic organism, for example one of the "common bacteria," is sown at the same time, the anthrax bacterium makes little or no growth and sooner or later dies out altogether. It is a remarkable thing that the same phenomenon is seen in the body even of those animals most susceptible to anthrax, leading to the astonishing result that anthrax bacteria can be introduced in profusion into an animal, which yet does not develop the disease; it is only necessary to add some "common 'bacteria" at the same time to the liquid containing the suspension of anthrax bacteria. These facts perhaps justify the highest hopes for therapeutics.{{ |

In 1876, German biologist ] discovered that a bacterium ('']'') was the causative pathogen of ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Koch |first=Robert |date=2010 |orig-year=1876 |others=Robert Koch-Institut |title=Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis|trans-title=The Etiology of Anthrax Disease, Based on the Developmental History of Bacillus Anthracis |url=https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/5139|journal=Cohns Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen |issn=0005-8041 |language=de |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=277 (1–22)|doi=10.25646/5064}}</ref> which became the first demonstration that a specific bacterium caused a specific disease and the first direct evidence of ]s.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lakhtakia|first=Ritu|date=2014|title=The Legacy of Robert Koch: Surmise, search, substantiate|journal=Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=e37–41 |doi=10.12816/0003334 |pmc=3916274 |pmid=24516751}}</ref> In 1877, French biologists ] and Jules Francois Joubert observed that cultures of anthrax bacilli, when contaminated with moulds, could be successfully inhibited.<ref name=":14">{{cite journal|last=Shama |first=G. |date=September 2016|title=La Moisissure et la Bactérie: Deconstructing the fable of the discovery of penicillin by Ernest Duchesne|url=https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/2134/21810|journal=Endeavour|issn=0160-9327|volume=40|issue=3|pages=188–200|doi=10.1016/j.endeavour.2016.07.005|pmid=27496372}}</ref> Reporting in the ''Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences'', they concluded:{{blockquote|Neutral or slightly alkaline urine is an excellent medium for the bacteria. If the urine is sterile and the culture pure the bacteria multiply so fast that in the course of a few hours their filaments fill the fluid with a downy felt. But if when the urine is inoculated with these bacteria an aerobic organism, for example one of the "common bacteria," is sown at the same time, the anthrax bacterium makes little or no growth and sooner or later dies out altogether. It is a remarkable thing that the same phenomenon is seen in the body even of those animals most susceptible to anthrax, leading to the astonishing result that anthrax bacteria can be introduced in profusion into an animal, which yet does not develop the disease; it is only necessary to add some "common 'bacteria" at the same time to the liquid containing the suspension of anthrax bacteria. These facts perhaps justify the highest hopes for therapeutics.<ref>Quoted and translated by Howard Florey in {{harvnb|Florey|1946|pp=101–102}}. For the French original, see {{cite report |title=Charbon et septicémie: lectures faites à l'Académie des sciences et à l'Académie de médecine |first1=Louis |last1=Pasteur |author-link1=Louis Pasteur |last2=Joubert |first2=Jules |author-link2=:fr:Jules Joubert |date=1877 |p=14 |url=https://wellcomecollection.org/works/srramk3e/items |access-date=9 July 2023 |language=fr}}</ref> }} | ||

| The phenomenon was described by Pasteur and Koch as antibacterial activity and was named "antibiosis" by French biologist ] in 1877.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Foster|first1=W.|last2=Raoult|first2=A.|date=1974|title=Early descriptions of antibiosis|journal=The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners|volume=24|issue=149|pages=889–894|pmc=2157443|pmid=4618289}}</ref><ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last=Brunel|first=J.|date=1951|title=Antibiosis from Pasteur to Fleming |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14873929 |journal=Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences |issn=0022-5045 |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=287–301 |doi=10.1093/jhmas/vi.summer.287|pmid=14873929}}</ref> (The term antibiosis, meaning "against life", was adopted as "]" by American biologist and later Nobel laureate ] in 1947.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Waksman |first=S. A .|date=1947 |title=What is an antibiotic or an antibiotic substance? |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20264541 |journal=Mycologia |issn=0027-5514 |volume=39 |issue=5 |pages=565–569 |doi=10.1080/00275514.1947.12017635|pmid=20264541}}</ref>) However, ]'s 1926 ''Microbe Hunters'' |

The phenomenon was described by Pasteur and Koch as antibacterial activity and was named "antibiosis" by French biologist ] in 1877.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Foster|first1=W.|last2=Raoult|first2=A.|date=1974|title=Early descriptions of antibiosis|journal=The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners|volume=24|issue=149|pages=889–894|pmc=2157443|pmid=4618289}}</ref><ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last=Brunel|first=J.|date=1951|title=Antibiosis from Pasteur to Fleming |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14873929 |journal=Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences |issn=0022-5045 |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=287–301 |doi=10.1093/jhmas/vi.summer.287|pmid=14873929}}</ref> (The term antibiosis, meaning "against life", was adopted as "]" by American biologist and later Nobel laureate ] in 1947.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Waksman |first=S. A .|date=1947 |title=What is an antibiotic or an antibiotic substance? |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20264541 |journal=Mycologia |issn=0027-5514 |volume=39 |issue=5 |pages=565–569 |doi=10.1080/00275514.1947.12017635|pmid=20264541}}</ref>) However, ]'s 1926 ''Microbe Hunters'' notes that Pasteur believed that this was contamination by other bacteria rather than by mould.<ref>{{harvnb|Kruif|1996|p=157}} "At once Pasteur jumped to a fine idea: "If the harmless bugs from the air choke out the anthrax bacilli in the bottle, they will do it in the body too! It is a kind of dog-eat-dog!” shouted Pasteur, (...) Pasteur gravely announced: "That there were high hopes for the cure of disease from this experiment", but that is the last you hear of it, for Pasteur was never a man to give the world of science the benefit of studying his failures."</ref> In 1887, Swiss physician ] developed a test method using glass plate to see bacterial inhibition and found similar results.<ref name=":15" /> Using his gelatin-based culture plate, he grew two different bacteria and found that their growths were inhibited differently, as he reported: | ||

| {{blockquote|I inoculated on the untouched cooled plate alternate parallel strokes of ''B. fluorescens'' ]''] and ''Staph. pyogenes'' ]'' ]... ''B. fluorescens'' grew more quickly... is not a question of overgrowth or crowding out of one by another quicker-growing species, as in a garden where luxuriantly growing weeds kill the delicate plants. Nor is it due to the utilization of the available foodstuff by the more quickly growing organisms, rather there is an antagonism caused by the secretion of specific, easily diffusible substances which are inhibitory to the growth of some species but completely ineffective against others.{{sfn|Florey|1946|p=102}} }} | {{blockquote|I inoculated on the untouched cooled plate alternate parallel strokes of ''B. fluorescens'' ]''] and ''Staph. pyogenes'' ]'' ]... ''B. fluorescens'' grew more quickly... is not a question of overgrowth or crowding out of one by another quicker-growing species, as in a garden where luxuriantly growing weeds kill the delicate plants. Nor is it due to the utilization of the available foodstuff by the more quickly growing organisms, rather there is an antagonism caused by the secretion of specific, easily diffusible substances which are inhibitory to the growth of some species but completely ineffective against others.{{sfn|Florey|1946|p=102}} }} | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

| ===Background === | ===Background === | ||

| ], London]] | ], London]] | ||

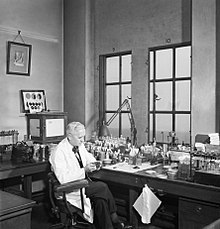

| Penicillin was discovered by a Scottish physician, ] in 1928. While working at ], Fleming was investigating the pattern of variation in ''S. aureus''.<ref name=":02">{{cite journal |last= Lalchhandama |first=K. |date=2020 |title=Reappraising Fleming's Snot and Mould |journal=Science Vision |volume=20 |issue=1 |pages=29–42 |issn=0975-6175 |doi=10.33493/scivis.20.01.03 |doi-access=free}}</ref> He was inspired by the discovery of an Irish physician, ], and his two students, C.R. Boland and R.A.Q. O’Meara, at ], in 1927''.'' Bigger and his students found that when they cultured a particular strain of ''S. aureus,'' which they had designated "Y" and isolated a year earlier from the ] of a patient's axillary ], the bacterium grew into a variety of strains. They published their discovery as |

Penicillin was discovered by a Scottish physician, ] in 1928. While working at ], Fleming was investigating the pattern of variation in ''S. aureus''.<ref name=":02">{{cite journal |last= Lalchhandama |first=K. |date=2020 |title=Reappraising Fleming's Snot and Mould |journal=Science Vision |volume=20 |issue=1 |pages=29–42 |issn=0975-6175 |doi=10.33493/scivis.20.01.03 |doi-access=free}}</ref> He was inspired by the discovery of an Irish physician, ], and his two students, C.R. Boland and R.A.Q. O’Meara, at ], in 1927''.'' Bigger and his students found that when they cultured a particular strain of ''S. aureus,'' which they had designated "Y" and isolated a year earlier from the ] of a patient's axillary ], the bacterium grew into a variety of strains. They published their discovery as "Variant colonies of ''Staphylococcus aureus''" in ''],'' concluding: | ||

| {{blockquote|We were surprised and rather disturbed to find, on a number of plates, various types of colonies which differed completely from the typical ''aureus'' colony. Some of these were quite white; some, either white or of the usual colour were rough on the surface and with crenated margins.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Bigger |first1=J.W. |last2=Boland |first2=C.R. |last3=O'Meara |first3=R.A. |date=1927 |title=Variant colonies of Staphylococcus aureu s|journal=] |issn=0022-3417 |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=261–269 |doi=10.1002/path.1700300204}}</ref> }} | {{blockquote|We were surprised and rather disturbed to find, on a number of plates, various types of colonies which differed completely from the typical ''aureus'' colony. Some of these were quite white; some, either white or of the usual colour were rough on the surface and with crenated margins.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Bigger |first1=J.W. |last2=Boland |first2=C.R. |last3=O'Meara |first3=R.A. |date=1927 |title=Variant colonies of Staphylococcus aureu s|journal=] |issn=0022-3417 |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=261–269 |doi=10.1002/path.1700300204}}</ref> }} | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

| <blockquote>When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Tan |first1=S.Y. |last2=Tatsumura |first2=Y. |title = Alexander Fleming (1881–1955): Discoverer of penicillin |journal = Singapore Medical Journal |volume = 56 |issue = 7 |pages = 366–367 |date = July 2015 |pmid = 26243971 |pmc = 4520913 |doi = 10.11622/smedj.2015105 }}</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Tan |first1=S.Y. |last2=Tatsumura |first2=Y. |title = Alexander Fleming (1881–1955): Discoverer of penicillin |journal = Singapore Medical Journal |volume = 56 |issue = 7 |pages = 366–367 |date = July 2015 |pmid = 26243971 |pmc = 4520913 |doi = 10.11622/smedj.2015105 }}</ref></blockquote> | ||

| He concluded that the mould was releasing a substance that was inhibiting bacterial growth, and he produced culture broth of the mould and subsequently concentrated the antibacterial component.<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |last1 = Arseculeratne |first1=S.N. |last2=Arseculeratne |first2=G. |s2cid = 21424547 |title = A re-appraisal of the conventional history of antibiosis and Penicillin |journal = Mycoses |volume = 60 |issue = 5 |pages = 343–347 | date = May 2017 | pmid = 28144986 | doi = 10.1111/myc.12599 }}</ref> After testing against different bacteria, he found that the mould could kill only specific, ] bacteria.{{sfn|Pommerville|2014|p=807}} For example, '' |

He concluded that the mould was releasing a substance that was inhibiting bacterial growth, and he produced culture broth of the mould and subsequently concentrated the antibacterial component.<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |last1 = Arseculeratne |first1=S.N. |last2=Arseculeratne |first2=G. |s2cid = 21424547 |title = A re-appraisal of the conventional history of antibiosis and Penicillin |journal = Mycoses |volume = 60 |issue = 5 |pages = 343–347 | date = May 2017 | pmid = 28144986 | doi = 10.1111/myc.12599 }}</ref> After testing against different bacteria, he found that the mould could kill only specific, ] bacteria.{{sfn|Pommerville|2014|p=807}} For example, ''staphylococcus'', '']'', and diphtheria bacillus ('']'') were easily killed; but there was no effect on typhoid bacterium ('']'') and a bacterium once thought to cause influenza ('']''). He prepared a large-culture method from which he could obtain large amounts of the mould juice. He called this juice "penicillin", explaining the reason as "to avoid the repetition of the rather cumbersome phrase 'Mould broth filtrate'."<ref name="pmid69942002">{{cite journal|last=Fleming|first=Alexander |author-link=Alexander Fleming |year=1929 |title=On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to their use in the Isolation of ''B. influenzae'' |journal=British Journal of Experimental Pathology |volume=10 |issue=3 |pages=226–236 |pmc=2041430|pmid=2048009}}; Reprinted as {{cite journal |last=Fleming |first=A. |author-link=Alexander Fleming |year=1979|title=On the antibacterial action of cultures of a Penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzae |journal=British Journal of Experimental Pathology |volume=60 |issue=1 |pages=3–13 |pmc=2041430}}</ref> He invented the name on 7 March 1929.<ref name=":5" /> In his Nobel lecture he gave a further explanation, saying: | ||

| <blockquote>I have been frequently asked why I invented the name "Penicillin". I simply followed perfectly orthodox lines and coined a word which explained that the substance penicillin was derived from a plant of the genus ''Penicillium'' just as many years ago the word "]" was invented for a substance derived from the plant '']''.{{sfn|Fleming|1999|p=83}}</blockquote> | <blockquote>I have been frequently asked why I invented the name "Penicillin". I simply followed perfectly orthodox lines and coined a word which explained that the substance penicillin was derived from a plant of the genus ''Penicillium'' just as many years ago the word "]" was invented for a substance derived from the plant '']''.{{sfn|Fleming|1999|p=83}}</blockquote> | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

| The source of the fungal contamination in Fleming's experiment remained a speculation for several decades. Fleming suggested in 1945 that the fungal spores came through the window facing ]. This story was regarded as a fact and was popularised in literature,<ref name=":2">{{cite journal |last = Hare |first=R. | title = New Light on the History of Penicillin | journal = Medical History | volume = 26 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–24 | date = January 1982 | pmid = 7047933 | pmc = 1139110 | doi = 10.1017/S0025727300040758 }}</ref> starting with George Lacken's 1945 book ''The Story of Penicillin''.<ref name=":5" /> But it was later disputed by his co-workers including Pryce, who testified much later that Fleming's laboratory window was kept shut all the time.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Wyn Jones |first1=E. |last2=Wyn Jones |first2=R. G. | title = Merlin Pryce (1902–1976) and Penicillin: An Abiding Mystery | journal = Vesalius |issn=1373-4857 | volume = 8 | issue = 2 | pages = 6–25 | date = December 2002 | pmid = 12713008 }}</ref> Ronald Hare also agreed in 1970 that the window was most often locked because it was difficult to reach due to a large table with apparatuses placed in front of it. In 1966, La Touche told Hare that he had given Fleming thirteen specimens of fungi (ten from his lab) and only one from his lab was showing penicillin-like antibacterial activity.<ref name=":2" /> After this, a consensus developed that Fleming's mould had come from La Touche's lab, a floor below Fleming's, as spores which had drifted in through the open doors.<ref>{{Cite journal|last = Curry |first=J. |date=1981 |title=Obituary: C. J. La Touche |journal=Medical Mycology |volume=19 |issue=2 |page=164 |doi=10.1080/00362178185380261}}</ref> | The source of the fungal contamination in Fleming's experiment remained a speculation for several decades. Fleming suggested in 1945 that the fungal spores came through the window facing ]. This story was regarded as a fact and was popularised in literature,<ref name=":2">{{cite journal |last = Hare |first=R. | title = New Light on the History of Penicillin | journal = Medical History | volume = 26 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–24 | date = January 1982 | pmid = 7047933 | pmc = 1139110 | doi = 10.1017/S0025727300040758 }}</ref> starting with George Lacken's 1945 book ''The Story of Penicillin''.<ref name=":5" /> But it was later disputed by his co-workers including Pryce, who testified much later that Fleming's laboratory window was kept shut all the time.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Wyn Jones |first1=E. |last2=Wyn Jones |first2=R. G. | title = Merlin Pryce (1902–1976) and Penicillin: An Abiding Mystery | journal = Vesalius |issn=1373-4857 | volume = 8 | issue = 2 | pages = 6–25 | date = December 2002 | pmid = 12713008 }}</ref> Ronald Hare also agreed in 1970 that the window was most often locked because it was difficult to reach due to a large table with apparatuses placed in front of it. In 1966, La Touche told Hare that he had given Fleming thirteen specimens of fungi (ten from his lab) and only one from his lab was showing penicillin-like antibacterial activity.<ref name=":2" /> After this, a consensus developed that Fleming's mould had come from La Touche's lab, a floor below Fleming's, as spores which had drifted in through the open doors.<ref>{{Cite journal|last = Curry |first=J. |date=1981 |title=Obituary: C. J. La Touche |journal=Medical Mycology |volume=19 |issue=2 |page=164 |doi=10.1080/00362178185380261}}</ref> | ||

| Craddock developed severe infection of the ] (]) and had undergone surgery. Fleming made use of the surgical opening of the nasal passage and started injecting penicillin on 9 January 1929 but without any effect, probably because the infection was with ''H. influenzae'', a bacterium unsusceptible to penicillin.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Hare |first=R. |date=1982 |title=New light on the history of penicillin |journal=Medical History |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=1–24 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300040758 |pmc=1139110 |pmid=7047933}}</ref> Fleming gave some of his original penicillin samples to his colleague, surgeon Arthur Dickson Wright for clinical testing in 1928.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wainwright |first1=M. |last2=Swan|first2=H.T. |date=1987|title=The Sheffield penicillin story|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0269915X87800228 |journal=Mycologist |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=28–30 |doi=10.1016/S0269-915X(87)80022-8}}</ref><ref name=":11">{{Cite journal |last=Wainwright |first=Milton |date=1990 |title=Besredka's "antivirus" in relation to Fleming's initial views on the nature of penicillin|journal=Medical History |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=79–85 |doi=10.1017/S0025727300050286 |pmc=1036002 |pmid=2405221}}</ref> Although Wright reportedly said that it "seemed to work satisfactorily," there are no records of its use.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wainwright |first=M. |date=1987 |title=The history of the therapeutic use of crude penicillin |journal=] |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=41–50 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300046305 |pmc=1139683 |pmid=3543562}}</ref> Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in ], was the first to successfully use penicillin for medical treatment.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wainwright |first=Milton |date=1989 |title=Moulds in Folk Medicine |url=http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0015587X.1989.9715763 |journal=Folklore |volume=100 |issue=2 |pages=162–166 |doi=10.1080/0015587X.1989.9715763}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Dr Cecil George Paine - Unsung Medical Heroes - Blackwell's Bookshop Online|url=https://blackwells.co.uk/jsp/promo/umh.jsp?action=more&id=18|access-date=2020-10-19|website=blackwells.co.uk}}</ref> He |

Craddock developed severe infection of the ] (]) and had undergone surgery. Fleming made use of the surgical opening of the nasal passage and started injecting penicillin on 9 January 1929 but without any effect, probably because the infection was with ''H. influenzae'', a bacterium unsusceptible to penicillin.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Hare |first=R. |date=1982 |title=New light on the history of penicillin |journal=Medical History |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=1–24 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300040758 |pmc=1139110 |pmid=7047933}}</ref> Fleming gave some of his original penicillin samples to his colleague, surgeon Arthur Dickson Wright for clinical testing in 1928.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wainwright |first1=M. |last2=Swan|first2=H.T. |date=1987|title=The Sheffield penicillin story|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0269915X87800228 |journal=Mycologist |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=28–30 |doi=10.1016/S0269-915X(87)80022-8}}</ref><ref name=":11">{{Cite journal |last=Wainwright |first=Milton |date=1990 |title=Besredka's "antivirus" in relation to Fleming's initial views on the nature of penicillin|journal=Medical History |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=79–85 |doi=10.1017/S0025727300050286 |pmc=1036002 |pmid=2405221}}</ref> Although Wright reportedly said that it "seemed to work satisfactorily," there are no records of its use.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wainwright |first=M. |date=1987 |title=The history of the therapeutic use of crude penicillin |journal=] |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=41–50 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300046305 |pmc=1139683 |pmid=3543562}}</ref> In 1930 and 1931, Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in ], was the first to successfully use penicillin for medical treatment.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wainwright |first=Milton |date=1989 |title=Moulds in Folk Medicine |url=http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0015587X.1989.9715763 |journal=Folklore |volume=100 |issue=2 |pages=162–166 |doi=10.1080/0015587X.1989.9715763}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Dr Cecil George Paine - Unsung Medical Heroes - Blackwell's Bookshop Online|url=https://blackwells.co.uk/jsp/promo/umh.jsp?action=more&id=18|access-date=2020-10-19|website=blackwells.co.uk}}</ref> He attempted to treat ] (eruptions in beard follicles) with penicillin but was unsuccessful, probably because the drug did not penetrate deep enough into the skin. He cured three babies with ], an eye infection, and a local coal miner whose eye had become infected after an accident, but he did not publish his work.<ref>{{cite journal |last1= Wainwright |first1=M. |last2=Swan |first2=H.T. |title = C.G. Paine and the earliest surviving clinical records of penicillin therapy |journal = Medical History |volume = 30 |issue = 1 |pages = 42–56 |date = January 1986 |pmid = 3511336 |pmc = 1139580 |doi = 10.1017/S0025727300045026 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Alharbi |first1=Sulaiman Ali |last2=Wainwright |first2=Milton |last3=Alahmadi |first3=Tahani Awad |last4=Salleeh |first4=Hashim Bin |last5=Faden |first5=Asmaa A. |last6=Chinnathambi |first6=Arunachalam |date=2014 |title=What if Fleming had not discovered penicillin? |journal=Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences |volume=21 |issue=4 |pages=289–293 |doi=10.1016/j.sjbs.2013.12.007 |pmc=4150221 |pmid=25183937}}</ref> | ||

| === Reception and publication === | === Reception and publication === | ||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

| <blockquote>In addition to its possible use in the treatment of bacterial infections, penicillin is certainly useful to the bacteriologist for its power of inhibiting unwanted microbes in bacterial cultures so that penicillin-insensitive bacteria can readily be isolated. A notable instance of this is the very easy isolation of Pfeiffer's bacillus of influenza when penicillin is used ... It is suggested that it may be an efficient antiseptic for application to, or injection into, areas infected with penicillin-sensitive microbes.<ref name="pmid6994200" /></blockquote> | <blockquote>In addition to its possible use in the treatment of bacterial infections, penicillin is certainly useful to the bacteriologist for its power of inhibiting unwanted microbes in bacterial cultures so that penicillin-insensitive bacteria can readily be isolated. A notable instance of this is the very easy isolation of Pfeiffer's bacillus of influenza when penicillin is used ... It is suggested that it may be an efficient antiseptic for application to, or injection into, areas infected with penicillin-sensitive microbes.<ref name="pmid6994200" /></blockquote> | ||

| G. E. Breen, a fellow member of the ], once asked Fleming if he thought it would ever be possible to make practical use of penicillin. Fleming gazed vacantly for a moment and then replied, "I don't know. It's too unstable. It will have to be purified, and I can't do that by myself."<ref name=":02" /> In 1941, the '']'' reported that |

G. E. Breen, a fellow member of the ], once asked Fleming if he thought it would ever be possible to make practical use of penicillin. Fleming gazed vacantly for a moment and then replied, "I don't know. It's too unstable. It will have to be purified, and I can't do that by myself."<ref name=":02" /> In 1941, the '']'' reported that | ||

| <blockquote>The original colony of this mould, which proved to be ''Penicillium notatum'',{{sic}} inhibited the growth of staphylococci in its vicinity, and fluid cultures of it contained a substance, since known as "penicillin", which was strongly inhibitory to the growth of various mainly Gram-positive bacteria. It came to be used at St. Mary's Hospital and elsewhere as an ingredient in selective culture media, and does not appear to have been considered as possibly useful from any other point of view.<ref>{{cite journal |title = Annotations |journal = British Medical Journal |volume = 2 |issue = 4208 |pages = 310–312 |date = August 1941 |pmid = 20783842 |pmc = 2162429 |doi = 10.1136/bmj.2.4208.310 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last = Fleming |first=A. |title = Penicillin |journal = British Medical Journal |date = September 1941 |volume = 2 |issue = 4210 |page = 386 |pmc = 2162878 |doi=10.1136/bmj.2.4210.386}}</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>The original colony of this mould, which proved to be ''Penicillium notatum'',{{sic}} inhibited the growth of staphylococci in its vicinity, and fluid cultures of it contained a substance, since known as "penicillin", which was strongly inhibitory to the growth of various mainly Gram-positive bacteria. It came to be used at St. Mary's Hospital and elsewhere as an ingredient in selective culture media, and does not appear to have been considered as possibly useful from any other point of view.<ref>{{cite journal |title = Annotations |journal = British Medical Journal |volume = 2 |issue = 4208 |pages = 310–312 |date = August 1941 |pmid = 20783842 |pmc = 2162429 |doi = 10.1136/bmj.2.4208.310 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last = Fleming |first=A. |title = Penicillin |journal = British Medical Journal |date = September 1941 |volume = 2 |issue = 4210 |page = 386 |pmc = 2162878 |doi=10.1136/bmj.2.4210.386}}</ref></blockquote> | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

| In 1944, ] determined how penicillin acts, and showed that it has no lytic effects on mature organisms, including staphylococci; ] occurs only if penicillin acts on bacteria during their initial stages of division and growth, when it interferes with the metabolic process that forms the ]. This brought Fleming's explanation into question, for the mould had to have been there before the staphylococci. Over the next twenty years, all attempts to replicate Fleming's results failed. In 1964, Ronald Hare took up the challenge. Like those before him, he found he could not get the mould to grow properly on a plate containing staphylococci colonies. He re-examined Fleming's paper and images of the original Petri dish. He attempted to replicate the original layout of the dish so there was a large space between the staphylococci. He was then able to get the mould to grow, but it had no effect on the bacteria.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=191–192}}{{sfn|Hare|1970|pp=70–74}} | In 1944, ] determined how penicillin acts, and showed that it has no lytic effects on mature organisms, including staphylococci; ] occurs only if penicillin acts on bacteria during their initial stages of division and growth, when it interferes with the metabolic process that forms the ]. This brought Fleming's explanation into question, for the mould had to have been there before the staphylococci. Over the next twenty years, all attempts to replicate Fleming's results failed. In 1964, Ronald Hare took up the challenge. Like those before him, he found he could not get the mould to grow properly on a plate containing staphylococci colonies. He re-examined Fleming's paper and images of the original Petri dish. He attempted to replicate the original layout of the dish so there was a large space between the staphylococci. He was then able to get the mould to grow, but it had no effect on the bacteria.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=191–192}}{{sfn|Hare|1970|pp=70–74}} | ||

| Finally, on 1 August 1966, Hare was able to duplicate Fleming's results. However, when he tried again a fortnight later, the experiment failed. He considered whether the weather had anything to do with it, for ''Penicillium'' grows well in cold temperatures, but staphylococci |

Finally, on 1 August 1966, Hare was able to duplicate Fleming's results. However, when he tried again a fortnight later, the experiment failed. He considered whether the weather had anything to do with it, for ''Penicillium'' grows well in cold temperatures, but staphylococci do not. He conducted a series of experiments with the temperature carefully controlled, and found that penicillin would be reliably "rediscovered" when the temperature was below {{convert|68|F|C|order=flip}}, but never when it was above {{convert|90|F|C|order=flip}}. He consulted the weather records for 1928, and found that, as in 1966, there was a heat wave in mid-August followed by nine days of cold weather starting on 28 August that greatly favoured the growth of the mould.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=191–192}}{{sfn|Wilson|1976|pp=74–81}}{{sfn|Hare|1970|pp=70–74}} | ||

| ==Isolation == | ==Isolation == | ||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

| The Oxford team's first task was to obtain a sample of penicillin mould. This turned out to be easy. Margaret Campbell-Renton, who had worked with ], Florey's predecessor, revealed that Dreyer had been given a sample of the mould by Fleming in 1930 for his work on ]s, viruses that infect bacteria. Dreyer had lost all interest in penicillin when he discovered that it was not a bacteriophage.{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=64–65}}{{sfn|Wilson|1976|p=156}} He had died in 1934, but Campbell-Renton had continued to culture the mould.{{sfn|Sheehan|1982|p=30}} The next task was to grow sufficient mould to extract enough penicillin for laboratory experiments. The mould was cultured on a surface of liquid ]. Over the course of a few days it formed a yellow gelatinous skin covered in green spores. Beneath this, the liquid became yellow and contained penicillin. The team determined that the maximum yield was achieved in ten to twenty days.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=306–307}} | The Oxford team's first task was to obtain a sample of penicillin mould. This turned out to be easy. Margaret Campbell-Renton, who had worked with ], Florey's predecessor, revealed that Dreyer had been given a sample of the mould by Fleming in 1930 for his work on ]s, viruses that infect bacteria. Dreyer had lost all interest in penicillin when he discovered that it was not a bacteriophage.{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=64–65}}{{sfn|Wilson|1976|p=156}} He had died in 1934, but Campbell-Renton had continued to culture the mould.{{sfn|Sheehan|1982|p=30}} The next task was to grow sufficient mould to extract enough penicillin for laboratory experiments. The mould was cultured on a surface of liquid ]. Over the course of a few days it formed a yellow gelatinous skin covered in green spores. Beneath this, the liquid became yellow and contained penicillin. The team determined that the maximum yield was achieved in ten to twenty days.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=306–307}} | ||

| Most laboratory containers did not provide a large, flat area, and so were an uneconomical use of incubator space |

The mould needs air to grow, so cultivation required a container with a large surface area. Initially, glass bottles laid on their sides were used. Most laboratory containers did not provide a large, flat area, and so were an uneconomical use of ] space.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=306–307}} The ] was found to be practical, and was the basis for specially-made ceramic containers fabricated by J. Macintyre and Company in ]. These containers were rectangular in shape and could be stacked to save space.{{sfn|Williams|1984|p=118}} The Medical Research Council agreed to Florey's request for £300 ({{Inflation|UK|300|1940|fmt=eq|cursign=£|r=-3}}) and £2 each per week ({{Inflation|UK|2|1940|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}) for two (later) women factory hands. In 1943 Florey asked for their wages to be increased to £2 10s each per week ({{Inflation|UK|2.5|1943|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}).{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|p=325}} Heatley collected the first 174 of an order for 500 vessels on 22 December 1940, and they were seeded with spores three days later.{{sfn|Mason|2022|p=191}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

| == Trials == | == Trials == | ||

| Florey's team at Oxford showed that |

Florey's team at Oxford showed that penicillium extract killed different bacteria. Gardner and Orr-Ewing tested it against ] (against which it was most effective), ], streptococcus, staphylococcus, anthrax bacteria, ], ] bacterium ('']'') and ] bacteria. They observed bacteria attempting to grow in the presence of penicillin, and noted that penicillin was neither an enzyme that broke the bacteria down, nor an antiseptic that killed them; rather, it was a chemical that interfered with the process of ].{{sfn|Williams|1984|p=111}}<ref name=":10">{{Cite journal |last=Gaynes |first=Robert |date=2017 |title=The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use |url=http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/5/16-1556_article.htm |journal=] |issn=1080-6040 |volume=23 |issue=5 |pages=849–853 |doi=10.3201/eid2305.161556|pmc=5403050}}</ref> Jennings observed that it had no effect on ]s, and would therefore reinforce rather than hinder the body's natural defences against bacteria. She also found that unlike ]s, the first and only effective broad-spectrum antibiotic available at the time, it was not destroyed by ]. Medawar found that it did not affect the growth of tissue cells.{{sfn|Williams|1984|p=110}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] (now GlaxoSmithKline) laboratories to produce penicillin. The mould was grown on the surface of a liquid filled with nutrients. The stopper kept contaminants out while allowing the mould to breathe.]] | ||

| By March 1940 the Oxford team had sufficient impure penicillin to commence testing whether it was toxic. Over the next two months, Florey and Jennings conducted a series of experiments on rats, mice, rabbits and cats in which penicillin was administered in various ways. Their results showed that penicillin was destroyed in the stomach, but that all forms of injection were effective, as indicated by assay of the blood. It was found that penicillin was largely and rapidly excreted unchanged in their urine.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=308–312}} They found no evidence of toxicity in any of their animals. Had they tested against ]s research might have halted at this point, for penicillin is toxic to guinea pigs.{{sfn|Sheehan|1982|p=32}} | By March 1940 the Oxford team had sufficient impure penicillin to commence testing whether it was toxic. Over the next two months, Florey and Jennings conducted a series of experiments on rats, mice, rabbits and cats in which penicillin was administered in various ways. Their results showed that penicillin was destroyed in the stomach, but that all forms of injection were effective, as indicated by assay of the blood. It was found that penicillin was largely and rapidly excreted unchanged in their urine.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=308–312}} They found no evidence of toxicity in any of their animals. Had they tested against ]s research might have halted at this point, for penicillin is toxic to guinea pigs.{{sfn|Sheehan|1982|p=32}} | ||

| At 11:00 am on Saturday 25 May 1940, Florey injected eight mice with a virulent strain of ''streptococcus'', and then injected four of them with the penicillin solution. These four were divided into two groups: two of them received 10 milligrams once, and the other two received 5 milligrams at regular intervals. By 3:30 am on Sunday all four of the untreated mice were dead. All of the treated ones were still alive, although one died two days later.<ref name=":9" />{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=313–316}} Florey described the result to Jennings as "a miracle."{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|p=315}} | At 11:00 am on Saturday 25 May 1940, Florey injected eight mice with a virulent strain of ''streptococcus'', and then injected four of them with the penicillin solution. These four were divided into two groups: two of them received 10 milligrams once, and the other two received 5 milligrams at regular intervals. By 3:30 am on Sunday all four of the untreated mice were dead. All of the treated ones were still alive, although one died two days later.<ref name=":9" />{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=313–316}} Florey described the result to Jennings as "a miracle."{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|p=315}} | ||

| Jennings and Florey repeated the experiment on Monday with ten mice; this time, all six of the treated mice survived, as did one of the four controls. On Tuesday, they repeated it with sixteen mice, administering different does of penicillin. All six of the control mice died within 24 hours but the treated mice survived for several days, although they were all dead in nineteen days.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=313–316}} On 1 July, the experiment was performed with fifty mice, half of whom received penicillin. All fifty of the control mice died within sixteen hours while all but one of the treated mice were alive ten days later. Over the following weeks they performed experiments with batches of 50 or 75 mice, but using different bacteria. They found that penicillin was also effective against |

Jennings and Florey repeated the experiment on Monday with ten mice; this time, all six of the treated mice survived, as did one of the four controls. On Tuesday, they repeated it with sixteen mice, administering different does of penicillin. All six of the control mice died within 24 hours but the treated mice survived for several days, although they were all dead in nineteen days.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=313–316}} On 1 July, the experiment was performed with fifty mice, half of whom received penicillin. All fifty of the control mice died within sixteen hours while all but one of the treated mice were alive ten days later. Over the following weeks they performed experiments with batches of 50 or 75 mice, but using different bacteria. They found that penicillin was also effective against staphylococcus and ].{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=319–320}} Florey reminded his staff that promising as their results were, a human being weighed 3,000 times as much as a mouse.{{sfn|Mason|2022|p=152}} | ||

| The Oxford team reported their results in the 24 August 1940 issue of '']'' as "Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent" with names of the seven joint authors listed alphabetically. They concluded: | The Oxford team reported their results in the 24 August 1940 issue of '']'', a prestigious medical journal, as "Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent" with names of the seven joint authors listed alphabetically.<ref name=":9" />{{sfn|Mason|2022|p=156}} They concluded: | ||

| {{blockquote|The results are clear cut, and show that penicillin is active |

{{blockquote|The results are clear cut, and show that penicillin is active in vivo against at least three of the organisms inhibited in vitro. It would seem a reasonable hope that all organisms in high dilution in vitro will be found to be dealt with in vivo. Penicillin does not appear to be related to any chemotherapeutic substance at present in use and is particularly remarkable for its activity against the anaerobic organisms associated with ].<ref name=":9">{{Cite journal |last1=Chain |first1=E. |author-link1=Ernst Chain |last2=Florey |first2=H. W. |author-link2=Howard Florey |last3=Adelaide |first3=M. B. |last4=Gardner |first4=A. D. |author-link4=Arthur Duncan Gardner |last5=Heatley |first5=N. G. |author-link5=Norman Heatley |last6=Jennings |first6=M. A. |author-link6=Margaret Jennings (scientist) |last7=Orr-Ewing |first7=J. |last8=Sanders |first8=A. G. |date=1940 |title=Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8403666 |journal=] |issn=0140-6736 |volume=236 |issue=6104 |pages=226–228 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(01)08728-1 |pmid=8403666}}</ref>}} The publication attracted little attention; Florey would spend much of the next two years attempting to convince people of the significance of their results. One reader was Fleming, who paid them a visit on 2 September 1940. Florey and Chain gave him a tour of the production, extraction and testing laboratories, but he made no comment and did not even congratulate them on the work they had done. Some members of the Oxford team suspected that he was trying to claim some credit for it.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=322–324}}{{sfn|Mason|2022|pp=162–164}} | ||

| Unbeknown to the Oxford team, their ''Lancet'' article was read by ], ] and ] at Columbia University, and they were inspired to replicate the Oxford team's results. They obtained a culture of penicillium mould from Roger Reid at ], grown from a sample he had received from Fleming in 1935. They began growing the mould on 23 September, and on 30 September tested it against ], and confirmed the Oxford team's results. Meyer duplicated Chain's processes, and they obtained a small quantity of penicillin. On 15 October 1940, doses of penicillin were administered to two patients at the ] in New York City, Aaron Alston and Charles Aronson. They became the first persons to receive penicillin treatment in the United States.{{sfn|Bickel|1995|pp=124–129}}{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=69–73}} The Columbia team presented the results of their penicillin treatment of four patients at the annual meeting of the ] in ], on 5 May 1941. Their paper was reported on by ] in '']'' and generated great public interest.{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=69–73}}<ref>{{cite journal |title=Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent |last1=Dawson |first1=Martin H. |author-link1=Martin Henry Dawson |last2=Hobby |first2=Galdys L. |author-link2=Gladys Lounsbury Hobby |last3=Meyer |first3=Karl |author-link3=Karl Meyer (biochemist) |last4=Chaffee |first4=Eleanor |date=1 July 1941 |journal=] |issn=0021-9738 |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=433–465 |doi=10.1172/JCI101239}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title='Giant' Germicide Yielded by Mold; New Non-Toxic Drug Said to be the Most Powerful Germ Killer Ever Discovered |newspaper=The New York Times |first=William L. |last=Laurence |date=6 May 1941 |author-link=William L. Laurence |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1941/05/06/archives/giant-germicide-yielded-by-mold-new-nontoxic-drug-said-to-be-the.html |access-date=13 February 2023}}</ref> | Unbeknown to the Oxford team, their ''Lancet'' article was read by ], ] and ] at Columbia University, and they were inspired to replicate the Oxford team's results. They obtained a culture of penicillium mould from Roger Reid at ], grown from a sample he had received from Fleming in 1935. They began growing the mould on 23 September, and on 30 September tested it against ], and confirmed the Oxford team's results. Meyer duplicated Chain's processes, and they obtained a small quantity of penicillin. On 15 October 1940, doses of penicillin were administered to two patients at the ] in New York City, Aaron Alston and Charles Aronson. They became the first persons to receive penicillin treatment in the United States. He then treated two patients with ].{{sfn|Bickel|1995|pp=124–129}}{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=69–73}} The Columbia team presented the results of their penicillin treatment of the four patients at the annual meeting of the ] in ], on 5 May 1941. Their paper was reported on by ] in '']'' and generated great public interest.{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=69–73}}<ref>{{cite journal |title=Penicillin as a Chemotherapeutic Agent |last1=Dawson |first1=Martin H. |author-link1=Martin Henry Dawson |last2=Hobby |first2=Galdys L. |author-link2=Gladys Lounsbury Hobby |last3=Meyer |first3=Karl |author-link3=Karl Meyer (biochemist) |last4=Chaffee |first4=Eleanor |date=1 July 1941 |journal=] |issn=0021-9738 |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=433–465 |doi=10.1172/JCI101239}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title='Giant' Germicide Yielded by Mold; New Non-Toxic Drug Said to be the Most Powerful Germ Killer Ever Discovered |newspaper=The New York Times |first=William L. |last=Laurence |date=6 May 1941 |author-link=William L. Laurence |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1941/05/06/archives/giant-germicide-yielded-by-mold-new-nontoxic-drug-said-to-be-the.html |access-date=13 February 2023}}</ref> | ||

| ] medium, to encourage further penicillin growth.]] | ] medium, to encourage further penicillin growth.]] | ||

| At Oxford, Charles Fletcher volunteered to find test cases for human trials. Elva Akers, an Oxford woman dying from incurable cancer, agreed to be a test subject for the toxicity of penicillin. On 17 January 1941, he intravenously injected her with 100 mg of penicillin. Her temperature briefly rose, but otherwise she had no ill-effects. Florey reckoned that the fever was caused by ] in the penicillin; these were removed with improved ].{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=329–331}} Fletcher next identified an Oxford policeman, ], who |

At Oxford, Charles Fletcher volunteered to find test cases for human trials. Elva Akers, an Oxford woman dying from incurable cancer, agreed to be a test subject for the toxicity of penicillin. On 17 January 1941, he intravenously injected her with 100 mg of penicillin. Her temperature briefly rose, but otherwise she had no ill-effects. Florey reckoned that the fever was caused by ] in the penicillin; these were removed with improved ].{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=329–331}} Fletcher next identified an Oxford policeman, ], who had a severe facial infection involving streptococci and staphylococci which had developed from a small sore at the corner of his mouth. His whole face, eyes and scalp were swollen to the extent that he had an eye removed to relieve the pain.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=329–331}}<ref name="SW2" /> | ||

| On 12 February, Fletcher administered 200 mg of penicillin, following by 100 mg doses every three hours. Within a day of being given penicillin, Alexander started to recover; his temperature dropped and discharge from his ] wounds declined. By 17 February, his right eye had become normal. However, the researchers did not have enough penicillin to help him to a full recovery. Penicillin was recovered from his urine, but it was not enough. In early March he relapsed, and he died on 15 March. Because of this experience and the difficulty in producing penicillin, Florey changed the focus to treating children, who could be treated with smaller quantities of penicillin.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=329–331}}<ref name="SW2">{{cite web |year=2007 |title=Making Penicillin Possible: Norman Heatley Remembers |url=http://www.sciencewatch.com/interviews/norman_heatly.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070221041204/http://www.sciencewatch.com/interviews/norman_heatly.htm |archive-date=21 February 2007 |access-date=2007-02-13 |publisher=ScienceWatch }}</ref> | On 12 February, Fletcher administered 200 mg of penicillin, following by 100 mg doses every three hours. Within a day of being given penicillin, Alexander started to recover; his temperature dropped and discharge from his ] wounds declined. By 17 February, his right eye had become normal. However, the researchers did not have enough penicillin to help him to a full recovery. Penicillin was recovered from his urine, but it was not enough. In early March he relapsed, and he died on 15 March. Because of this experience and the difficulty in producing penicillin, Florey changed the focus to treating children, who could be treated with smaller quantities of penicillin.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=329–331}}<ref name="SW2">{{cite web |year=2007 |title=Making Penicillin Possible: Norman Heatley Remembers |url=http://www.sciencewatch.com/interviews/norman_heatly.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070221041204/http://www.sciencewatch.com/interviews/norman_heatly.htm |archive-date=21 February 2007 |access-date=2007-02-13 |publisher=ScienceWatch }}</ref> | ||

| Subsequently, several patients were treated successfully. The second was Arthur Jones, a 15-year-old boy with a streptococcal infection from a hip operation. He was given 100 mg every three hours for five days and recovered. Percy Hawkin, a 42-year-old labourer, had a {{convert|4|in|adj=on|order=flip}} ] on his back. He was given an initial 200 mg on 3 May followed by 100 mg every hour. The carbuncle completely disappeared. John Cox, a semi-comatose 4-year-old boy was treated starting on 16 May. He died on 31 May but the post-mortem indicated this was from a ruptured artery in the brain weakened by the disease, and there was no sign of infection. The fifth case, on 16 June, was a 14-year-old boy with an infection from a hip operation who made a full recovery.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=331–333}} | Subsequently, several patients were treated successfully. The second was Arthur Jones, a 15-year-old boy with a streptococcal infection from a hip operation. He was given 100 mg every three hours for five days and recovered. Percy Hawkin, a 42-year-old labourer, had a {{convert|4|in|adj=on|order=flip}} ] on his back. He was given an initial 200 mg on 3 May followed by 100 mg every hour. The carbuncle completely disappeared. John Cox, a semi-comatose 4-year-old boy was treated starting on 16 May. He died on 31 May but the post-mortem indicated this was from a ruptured artery in the brain weakened by the disease, and there was no sign of infection. The fifth case, on 16 June, was a 14-year-old boy with an infection from a hip operation who made a full recovery.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=331–333}} | ||

| In addition to increased production at the Dunn School, commercial production from a ] established by ] became available in January 1942, and Kembel, Bishop and Company delivered its first batch of {{convert|200|impgal|L|order=flip}} on 11 September. Florey decided that the time was ripe to conduct a second series of clinical trials. Ethel was placed in charge, but while Florey was a consulting pathologist at Oxford hospitals and therefore entitled to use their wards and services, Ethel, to his annoyance, was accredited merely as his assistant. Doctors tended to refer patients to the trial who were in desperate circumstances rather than the most suitable, but when penicillin did succeed, confidence in its efficacy rose.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=342–346}} | In addition to increased production at the Dunn School, commercial production from a ] established by ] became available in January 1942, and Kembel, Bishop and Company delivered its first batch of {{convert|200|impgal|L|order=flip}} on 11 September. Florey decided that the time was ripe to conduct a second series of clinical trials. Ethel Florey was placed in charge, but while Howard Florey was a consulting pathologist at Oxford hospitals and therefore entitled to use their wards and services, Ethel, to his annoyance, was accredited merely as his assistant. Doctors tended to refer patients to the trial who were in desperate circumstances rather than the most suitable, but when penicillin did succeed, confidence in its efficacy rose.{{sfn|MacFarlane|1979|pp=342–346}} | ||

| Ethel and Howard Florey published the results of clinical trials of penicillin in ''The Lancet'' on 27 March 1943, reporting the treatment of 187 cases of ] with penicillin.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=M.E. |last1=Florey |author-link=Mary Ethel Florey |title=General and Local Administration Of Penicillin |journal=] |issn=0140-6736 |volume=241 |issue=6239 |pages=387–397 |date=27 March 1943 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(00)41962-8}}</ref> It was upon this medical evidence that the British ] set up the Penicillin Committee on 5 April 1943. The committee consisted of ], Director General of Equipment, as |

Ethel and Howard Florey published the results of clinical trials of penicillin in ''The Lancet'' on 27 March 1943, reporting the treatment of 187 cases of ] with penicillin.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=M.E. |last1=Florey |author-link=Mary Ethel Florey |title=General and Local Administration Of Penicillin |journal=] |issn=0140-6736 |volume=241 |issue=6239 |pages=387–397 |date=27 March 1943 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(00)41962-8}}</ref> It was upon this medical evidence that the British ] set up the Penicillin Committee on 5 April 1943. The committee consisted of ], Director General of Equipment, as chairman, Fleming, Florey, Allison Sir ], head of the ] (MRC), and representatives from pharmaceutical companies.<ref name=":07">{{Cite journal|last=Allison|first=V. D.|date=1974|title=Personal recollections of Sir Almroth Wright and Sir Alexander Fleming.|journal=The Ulster Medical Journal|volume=43|issue=2|pages=89–98|pmc=2385475|pmid=4612919}}</ref> This led to mass production of penicillin by the next year.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Mathews |first=John A. |date=2008 |title=The Birth of the Biotechnology Era: Penicillin in Australia, 1943–80 |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020802459306 |journal=Prometheus |volume=26 |issue=4 |pages=317–333 |doi=10.1080/08109020802459306 |s2cid=143123783}}</ref> | ||

| == Deep submergence for industrial production == | == Deep submergence for industrial production == | ||

| Knowing that large-scale production for medical use was futile in a |

Knowing that large-scale production for medical use was futile in a laboratory, the Oxford team tried to convince the war-torn British government and private companies for mass production, but the initial response was muted. In April 1941, ] met with Florey, and they discussed the difficulty of producing sufficient penicillin to conduct clinical trails. Weaver arranged for the Rockefeller Foundation to fund a three-month visit to the United States for Florey and a colleague to explore the possibility of production of penicillin there.{{sfn|Williams|1984|pp=125–128}} Florey and Heatley left for the United States by air on 27 June 1941.<ref name="Chain">{{cite web|title=Discovery and Development of Penicillin: International Historic Chemical Landmark|url=https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190628035235/https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html|archive-date=28 June 2019|access-date=15 July 2019|publisher=]|location=Washington, D.C.}}</ref> Knowing that mould samples kept in vials could be easily lost, they smeared their coat pockets with the mould.<ref name=":10" /> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 131: | Line 129: | ||

| Coghill made ] available to work on penicillin with Heatley, while Florey left to see if he could arrange for a pharmaceutical company to manufacture penicillin. As a first step to increasing yield, Moyer replaced ] in the growth media with ]. An even larger increase occurred when Moyer added ], a byproduct of the corn industry that the NRRL routinely tried in the hope of finding more uses for it. The effect on penicillin was dramatic; Heatley and Moyer found that it increased the yield tenfold.<ref name="Chain" /> | Coghill made ] available to work on penicillin with Heatley, while Florey left to see if he could arrange for a pharmaceutical company to manufacture penicillin. As a first step to increasing yield, Moyer replaced ] in the growth media with ]. An even larger increase occurred when Moyer added ], a byproduct of the corn industry that the NRRL routinely tried in the hope of finding more uses for it. The effect on penicillin was dramatic; Heatley and Moyer found that it increased the yield tenfold.<ref name="Chain" /> | ||

| At the ] in March 1942, Anne Sheafe Miller, the wife of ]'s athletics director, Ogden D. Miller, was |

At the ] in March 1942, Anne Sheafe Miller, the wife of ]'s athletics director, Ogden D. Miller, was succumming to a streptococcal septicaemia contracted after a ]. Her doctor, John Bumstead, was also treating John Fulton for an infection at the time. He knew that Fulton knew Florey, and that Florey's children were staying with him. He went to Fulton to plead for some penicillin. Florey had returned to the UK, but Heatley was still in the United States, working with Merck. A phone call to Richards released 5.5 grams of penicillin earmarked for a clinical trial, which was despatched from Washington, D. C., by air. The effect was dramatic; within 48 hours her {{convert|106|F|C|order=flip}} fever had abated and she was eating again. Her blood culture count had dropped 100 to 150 bacteria colonies per millilitre to just one. Bumstead suggested reducing the penicillin dose from 200 milligrams; Heatley told him not to. Heatley subsequently came to New Haven, where he collected her urine; about 3 grams of penicillin were recovered. Miller made a full recovery, and lived until 1999.<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Fulton, Penicillin and Chance |magazine=Yale Medicine Magazine |date=Fall 1999 – Winter 2000 |url=https://medicine.yale.edu/news/yale-medicine-magazine/article/fulton-penicillin-and-chance/ |access-date=16 February 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Ogden D. Miller, 73, Retired Educator |date=15 February 1978 |at=Section D, p. 16 |newspaper=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1978/02/15/archives/ogden-d-miller-73-retired-educator-exgunnery-school-headmaster.html |access-date=16 February 2023}}</ref>{{sfn|Bickel|1995|pp=175–178}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Until May 1943, almost all penicillin was produced using the shallow |

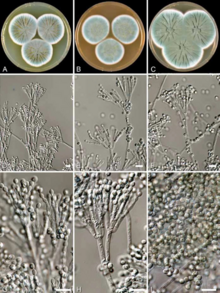

Until May 1943, almost all penicillin was produced using the shallow-pan method pioneered by the Oxford team,{{sfn|Hobby|1985|p=96}} but NRRL mycologist ] experimented with deep submergence production, in which penicillin mould was grown in a vat instead of a shallow dish. The initial results were disappointing; penicillin cultured in this manner yielded only three to four Oxford units per cubic centimetre, compared to twenty for surface cultures.{{sfn|Williams|1984|pp=133–134}} He got the help of U.S. Army's ] to search for similar mould in different parts of the world. The best moulds were found to be those from ], ], and ]. The best sample, however, was from a ] sold in a Peoria fruit market in 1943. The mould was identified as '']'' and designated as ''NRRL 1951'' or ''cantaloupe strain''.<ref name=":13" />{{sfn|Wilson|1976|pp=198–200}} The spores may have escaped from the NRRL.{{sfn|Williams|1984|p=146}}{{efn|On 17 August 2021, ] ] signed a bill designating it as the official State Microbe of Illinois.<ref name="Mouldy Mary">{{cite web |title=The Enduring Mystery of 'Moldy Mary' |publisher=US Department of Agriculture |url=https://tellus.ars.usda.gov/stories/articles/the-enduring-mystery-of-moldy-mary/ |access-date=12 February 2023}}</ref>}}{{efn|There is a popular story that Mary K. Hunt (or Mary Hunt Stevens),<ref>{{cite journal |last=Bentley |first=Ronald |date=2009 |title=Different roads to discovery; Prontosil (hence sulfa drugs) and penicillin (hence β-lactams) |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10295-009-0553-8|journal=Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology |volume=36 |issue=6 |pages=775–786 |doi=10.1007/s10295-009-0553-8 |pmid=19283418|s2cid=35432074}}</ref> a staff member of Raper's, collected the mould;<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kardos |first1=Nelson |last2=Demain |first2=Arnold L. |date=2011 |title=Penicillin: the medicine with the greatest impact on therapeutic outcomes |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00253-011-3587-6 |journal=Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology |volume=92 |issue=4 |pages=677–687 |doi=10.1007/s00253-011-3587-6 |pmid=21964640 |s2cid=39223087}}</ref> for which she had been popularised as "Mouldy Mary".<ref>{{cite web |last=Bauze |first=Robert |date=1997 |title=Editorial: Howard Florey and the penicillin story |url=https://www.proquest.com/openview/d5ed3749f4eb8b5b8bbe9d4ac3d955fd/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=11254 |access-date=2021-01-04 |publisher=Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery}}</ref><ref name="Mouldy Mary" /> But Raper remarked this story as a "folklore" and that the fruit was delivered to the lab by a woman from the Peoria fruit market.<ref name=":13" />}} | ||

| Between 1941 and 1943, Moyer, Coghill and Kenneth Raper developed methods for industrialized penicillin production and isolated higher-yielding strains of the ''Penicillium'' fungus.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/nov2003.html |title=''Penicillium chrysogenum'' (aka ''P. notatum''), the natural source for the wonder drug penicillin, the first antibiotic |work=Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for November 2003 }}</ref> To improve upon that strain, researchers at the ] subjected NRRL 1951 to ]s to produce mutant strain designated X-1612 that produced 300 per |

Between 1941 and 1943, Moyer, Coghill and Kenneth Raper developed methods for industrialized penicillin production and isolated higher-yielding strains of the ''Penicillium'' fungus.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/nov2003.html |title=''Penicillium chrysogenum'' (aka ''P. notatum''), the natural source for the wonder drug penicillin, the first antibiotic |work=Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for November 2003 }}</ref> To improve upon that strain, researchers at the ] subjected NRRL 1951 to ]s to produce a mutant strain designated X-1612 that produced 300 milligrams penicillin per litre of mould, twice as much as NRRL 1951. In turn, researchers at the ] used ] radiation on X-1612 to produce a strain designated Q-176. This produced more than twice the penicillin that X-1612 produced, but in the form of the less desirable penicillin K. ] was added to switch it to producing the highly potent penicillin G. This strain could produce up to 550 milligrams of penicillin per litre.{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=100–101, 234}}<ref name="Penicillin Production">{{cite web |last1=Mestrovic |first1=Tomislav |title=Penicillin Production |url=https://www.news-medical.net/health/Penicillin-Production.aspx |date=13 May 2010 }}</ref>{{sfn|Wilson|1976|pp=198–200}} | ||

| ⚫ | Pfizer was a small ] company that specialised in making ], but it had experience with ] techniques. Its vice president, ], whose daughter had died from an infection, put all of Pfizer's resources into the development of a practical deep submergence technique.{{sfn|Bud|2007|pp=44–45}} The company invested $2.98 million of its own money in penicillin in 1943 and 1944. (equivalent to ${{inflation|US|2.98|1944}} million in {{Inflation/year|US}}). Pfizer scientists ], G. M. Shull, E. M. Weber, A. C. Finlay and E. J. Ratajak worked on the fermentation process while R. Pasternak, W. J. Smith, V. Bogert and P. Regna developed extraction techniques.{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=183–185}} | ||

| ] ]] | ] ]] | ||

| ⚫ | Pfizer was a small ] company that specialised in making ], but it had experience |

||

| Now that they had a mould that grew well submerged and produced an acceptable amount of penicillin, the next challenge was to provide the required air to the mould for it to grow. This was solved using an ], but aeration caused severe foaming of the corn steep. The foaming problem was solved by the introduction of an anti-foaming agent, glyceryl monoricinoleate. The technique also involved cooling and mixing.<ref name="Discovery and Development of Penicillin">{{cite web |title=Discovery and Development of Penicillin |publisher= American Chemical Society |url=https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html |access-date=12 February 2023}}</ref> | Now that they had a mould that grew well submerged and produced an acceptable amount of penicillin, the next challenge was to provide the required air to the mould for it to grow. This was solved using an ], but aeration caused severe foaming of the corn steep. The foaming problem was solved by the introduction of an anti-foaming agent, glyceryl monoricinoleate. The technique also involved cooling and mixing.<ref name="Discovery and Development of Penicillin">{{cite web |title=Discovery and Development of Penicillin |publisher= American Chemical Society |url=https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html |access-date=12 February 2023}}</ref> | ||

| Pfizer opened a pilot plant with a {{convert|2,000|USgal|L|order=flip}} ] in August 1943 and Ratajak delivered the first penicillin liquor from it on 27 August. The one tank was soon producing half the company's output. Smith then decided to construct a full-scale production plant. The nearby Rubel Ice plant was acquired on 20 September 1943 and converted into the first deep |

Pfizer opened a pilot plant with a {{convert|2,000|USgal|L|adj=on|order=flip}} ] in August 1943 and Ratajak delivered the first penicillin liquor from it on 27 August. The one tank was soon producing half the company's output. Smith then decided to construct a full-scale production plant. The nearby Rubel Ice plant was acquired on 20 September 1943 and converted into the first deep-submergence production plant, with fourteen {{convert|34,000|USgal|L|adj=on|order=flip}} tanks. The work was carried out in five months under the leadership of ] and Edward J. Goett, and the plant opened on 1 March 1944.{{sfn|Bud|2007|pp=44–45}}{{sfn|Hobby|1985|pp=183–185}}<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.pfizer.com/about/history/1900_1950.jsp |title=1900–1950 |year=2009 |work=Exploring Our History |publisher=Pfizer Inc |access-date=2 August 2009}}</ref>{{-}} | ||

| == Mass production == | == Mass production == | ||

| === Australia === | === Australia === | ||

| In mid-1943 the Australian ] decided to produce penicillin in Australia. Colonel ], the Australian Army's Director of Hygiene and Pathology, was placed in charge of the effort. Keogh summoned Captain ], with whom he had worked at the ] (CSL) before the war, and Lieutenant H. H. Kretchmar, a chemist, and directed them to establish a production facility by Christmas. They set off on a fact-finding mission to the United States, where they visited NRRL and obtained penicillin cultures from |

In mid-1943 the Australian ] decided to produce penicillin in Australia. Colonel ], the Australian Army's Director of Hygiene and Pathology, was placed in charge of the effort. Keogh summoned Captain ], with whom he had worked at the ] (CSL) before the war, and Lieutenant H. H. Kretchmar, a chemist, and directed them to establish a production facility by Christmas. They set off on a fact-finding mission to the United States, where they visited NRRL and obtained penicillin cultures from Coghill. They also inspected the ] plant in ] and the ] plant at ]. A production plant was established at the CSL facilities in ], and the first Australian-made penicillin began reaching the troops in New Guinea in December 1943. By 1944, CSL was producing 400 million Oxford units per week, and there was sufficient penicillin production to allocate some for civilian use.{{sfn|Bickel|1995|pp=224–230}}{{sfn|Matthews|2008|pp=323–324}} | ||

| Wartime production was in bottles and flasks, but Bazeley made a second tour of facilities in the United States between September 1944 and March 1945 and was impressed by the progress made on deep submergence technology. In 1946 and 1947 he created a pilot deep submerged plant at CSL using small {{convert|10|impgal|L|adj=on|order=flip}} tanks to gain experience with the technique. Two {{convert|5,000|impgal|L|adj=on|order=flip}} tanks became operational in 1948, followed by eight more. During the 1950s and 1960s, CSL produced semisynthetic penicillin as well. Penicillin was also produced by F.H. Faulding in South Australia, Abbott Laboratories in New South Wales and ] in Victoria. By the 1970s there was a worldwide glut of penicillin, and Glaxo ceased production in 1975 and CSL in 1980.{{sfn|Matthews|2008|pp=324–327}} | Wartime production was in bottles and flasks, but Bazeley made a second tour of facilities in the United States between September 1944 and March 1945 and was impressed by the progress made on deep submergence technology. In 1946 and 1947 he created a pilot deep submerged plant at CSL using small {{convert|10|impgal|L|adj=on|order=flip}} tanks to gain experience with the technique. Two {{convert|5,000|impgal|L|adj=on|order=flip}} tanks became operational in 1948, followed by eight more. During the 1950s and 1960s, CSL produced ] penicillin as well. Penicillin was also produced by F.H. Faulding in South Australia, Abbott Laboratories in New South Wales and ] in Victoria. By the 1970s there was a worldwide glut of penicillin, and Glaxo ceased production in 1975 and CSL in 1980.{{sfn|Matthews|2008|pp=324–327}} | ||

| === Canada === | === Canada === | ||