| Revision as of 22:05, 1 April 2021 editBeenAroundAWhile (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users103,575 edits ←Blanked the pageTags: Blanking Manual revert← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:19, 9 April 2021 edit undoBeenAroundAWhile (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users103,575 editsNo edit summaryTags: content sourced to vanity press RevertedNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| | name = Old Los Angeles | |||

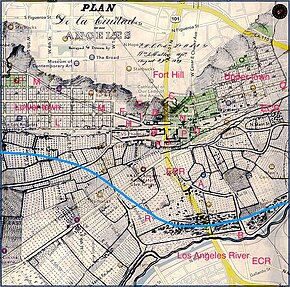

| | image_map = ] | |||

| | map_caption = '''Legend''' | |||

| <div style="text-align: left; direction: ltr; margin-right: 1em;"> | |||

| {{ordered list|type=A | |||

| | ], giant ], historical symbol of Los Angeles. | |||

| | ] (Macy Street) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] (original adobe jail) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ], home of the ''Asamblea'' when Los Angeles was the seat of government. | |||

| | ], courtroom/theatre was on the upper floor, market was on the ground floor, on top were the clocktower, copper dome, and spire. | |||

| | St. Athanasius' ], first Protestant church in Los Angeles, on Temple Road ("Salvation Alley"). | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ], Gen. Kearney's headquarters | |||

| | ]'s house | |||

| | ], to Cahuenga Valley & the back way to San Fernando. | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ], ''(Calle de las vides)'' | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] on the Zanja Madre | |||

| | Approximate run of the original ], to current USC, through La Cienega (The Swamp) of Leimert Park, and out to sea at Ballona Creek and Venice Beach. <br><br>LP: ] <br><br>ECR: ] | |||

| }} | |||

| </div> | |||

| | official_name = | |||

| }} | |||

| The modern ''History of ]'' began in 1781 when 44 settlers from ] established a permanent settlement in what is now ], as instructed by Spanish Governor of ] ] and authorized by Viceroy ]. After sovereignty changed from Mexico to the U.S. in 1848, great changes came from the completion of the ] line from ] to Los Angeles in 1885. “Overlanders” flooded in, mostly White ] from the Lower ] and ].<ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| Los Angeles had a strong economic base in farming, oil, tourism, real estate and movies. It grew rapidly with many suburban areas inside and outside the city limits. ] made the city world-famous, and ] brought new industry, especially high-tech aircraft construction. Politically the city was moderately conservative, with a weak labor union sector. | |||

| Since the 1960s, growth has slowed—and traffic delays have become infamous. Los Angeles was a pioneer in freeway development as the public transit system deteriorated. New arrivals, especially from ] and ], have transformed the demographic base since the 1960s. Old industries have declined, including farming, oil, military and aircraft, but tourism, entertainment and high-tech remain strong. | |||

| {{California history sidebar}} | |||

| ==Early history== | |||

| By 3000 B.C., the area was occupied by the ]-speaking people of the ] who fished, hunted sea mammals, and gathered wild seeds. They were later replaced by migrants — possibly fleeing drought in the ] — who spoke a ] called ]. The ] people called the Los Angeles region '''Yaa''' in ].<ref>Munro, Pamela, et al. ''Yaara' Shiraaw'ax 'Eyooshiraaw'a. Now You're Speaking Our Language: Gabrielino/Tongva/Fernandeño''. Lulu.com: 2008.{{self-published source|date=May 2020}}</ref> | |||

| By the 1700s A.D., there were 250,000 to 300,000 native people in California and 5,000 in the Los Angeles basin. The land occupied and used by the Tongva covered about {{convert|4,000|sqmi|km2}}. It included the enormous floodplain drained by the ] and ] rivers and the southern ], including the ], ], ], and ] Islands. They were part of a sophisticated group of trading partners that included the ] to the west, the ] and ] to the east, and the ] and ]s to the south. Their trade extended to the ] and included ].<ref name="trade">Smith, Gerald A. and James Clifford. 1965. ''Indian Slave Trade Along the Mojave Trail.'' San Bernardino California: San Bernardino County Museum.</ref> | |||

| The lives of the Tongva were governed by a set of religious and cultural practices that included belief in creative supernatural forces. They worshipped ], a creator god, and ], a female virgin god. Their Great Morning Ceremony was based on a belief in the afterlife. In a purification ritual, they drank '']'', a ] made from ] and salt water. Their language was called Kizh or Kij, and they practiced cremation.<ref name="gabrielinos">Johnson, Bernice Eastman. 1962. ''California's Gabrielino'' Indians. Highland Park, California: Southwest Museum Papers.</ref><ref name="religion">Bosca, Gerónimo. "Chinigchinish: An Historical Account of the Origins, Customs, and Traditions of the Indians of Alta California", in ''Life in California'', trans. Alfred Robinson. Santa Barbara: Peregrine.</ref><ref name="miller">Miller, Bruce. 1991. ''The Gabrielino''. Los Osos, California: Sand River Press.</ref> | |||

| Generations before the arrival of the Europeans, the Tongva had identified and lived in the best sites for human occupation. The survival and success of Los Angeles depended greatly on the presence of a nearby and prosperous Tongva village called ]. Its residents provided the colonists with seafood, fish, bowls, pelts, and baskets. For pay, they dug ditches, hauled water, and provided domestic help. They often intermarried with the Mexican colonists.<ref name="interaction">Kealhofer, 1991. ''Cultural Interaction During the Spanish Colonial Period''. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1991.</ref> | |||

| ==Spanish era: 1769-1821== | |||

| {{Main|Pueblo de Los Angeles|Los Angeles Pobladores}} | |||

| ]" facing the Plaza, 1869. The brick reservoir in the middle of the ] was the original terminus of the ].]] | |||

| In 1542 and 1602, the first Europeans to visit the region were Captain ] and Captain ]. The first permanent non-native presence began when the ] arrived on August 2, 1769.<ref name="indians" >McCawley, William. 1996. ''The First Angelinos: The Indians of Los Angeles''. Banning, California: Malki Museum Press and Ballena Press Cooperative. pp. 2–7</ref> | |||

| ===Plans for the pueblo=== | |||

| Although Los Angeles was a town that was founded by Mexican families from ], it was the Spanish governor of California who named the settlement. | |||

| In 1777, Governor ] toured ] and decided to establish ] for the support of the military '']s''. The new pueblos reduced the secular power of the ] by reducing the dependency of the military on them. At the same time, they promoted the development of industry and agriculture. | |||

| Governor de Neve identified ], ], and Los Angeles as sites for his new pueblos. His plans for them closely followed a set of Spanish city-planning laws contained in the ] promulgated by ] in 1573. Those laws were responsible for laying the foundations of the largest cities in the region at the time, including Los Angeles, ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="plaza">Estrada, William David. 2008. ''The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space''. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.</ref> | |||

| The Spanish system called for an open central plaza, surrounded by a fortified church, administrative buildings, and streets laid out in a grid, defining rectangles of limited size to be used for farming (''suertes'') and residences (''solares'').<ref name="low">Low, Setha M. 2000. On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.</ref> | |||

| It was in accordance with such precise planning—specified in the Law of the Indies—that Governor de Neve founded the pueblo of ], California's first ], on the great plain of ] on 29 November 1777.<ref name="towns">Cruz, Gilberto R. 1988. ''Let There Be Towns: Spanish Municipal Origins in the American Southwest, 1610–1810''. College Station, Texas: A&M University Press.</ref> | |||

| ===''Pobladores''=== | |||

| {{main|Los Angeles Pobladores}} | |||

| The Pobladores ("settlers") is the name given to the 44 original settlers, 22 adults and 22 children from Sonora, who founded the town. Of the 44, 20 of the settlers were of African American or Native American descent, making LA one of the few cities in the United States with such a diverse beginning. In December 1777, Viceroy ] and Commandant General ] gave approval for the founding of a civic municipality at Los Angeles and a new ''presidio'' at Santa Barbara. | |||

| Croix put the California lieutenant governor ] in charge of recruiting colonists for the new settlements. He was originally instructed to recruit 55 soldiers, 22 settlers with families and 1,000 head of livestock that included horses for the military. After an exhausting search that took him to ], Rosario, and Durango, Rivera y Moncada only recruited 12 settlers and 45 soldiers. Like the people of most towns in ] they were a mix of Indian and Spanish backgrounds. The ] Revolt killed 95 settlers and soldiers, including Rivera y Moncada.<ref name="bancroft">Bancroft, Hubert Howe. 1886''. History of California''. 7 volumes. San Francisco: History Company.</ref> | |||

| In his ''Reglamento'', the newly baptized Indians were no longer to reside in the mission but live in their traditional ''rancherías'' (villages). Governor de Neve's new plans for the Indians' role in his new town drew instant disapproval from the mission priests.<ref name="newlook">Kelsey, Harry. 1976. "A New Look at the Founding of Los Angeles." ''Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly''. 55:4, Winter. pp. 326–339.</ref> | |||

| Zúñiga's party arrived at the mission on 18 July 1781. Because they had arrived with ], they immediately were quarantined a short distance away from the mission. Members of the other party arrived at different times by August. They made their way to Los Angeles and probably received their land before September.<ref name="newlook" /> | |||

| ===Founding=== | |||

| The official date for the founding of the city is September 4, 1781.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.turismobailen.es/en/born-in-bailen/127-the-founder-of-the-city-of-los-angeles|title=The founder of the city of Los Angeles|website=www.turismobailen.es|access-date=11 December 2018}}</ref> The families had arrived from ] earlier in 1781, in two groups, and some of them had most likely been working on their assigned plots of land since the early summer.<ref name="history">Ríos-Bustamante, Antonio. ''Mexican Los Ángeles: A Narrative and Pictoral History'', Nuestra Historia Series, Monograph No. 1. (Encino: Floricanto Press, 1992), 50–53. {{OCLC|228665328}}.</ref> | |||

| The name first given to the settlement is debated. Historian Doyce B. Nunis has said that the Spanish named it "El Pueblo de la Reina de los Angeles" ("The Town of the Queen of the Angels"). For proof, he pointed to a map dated 1785, where that phrase was used. ], the diocesan archivist, replied, however, that the name given by the founders was "El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de ]", or "the town of ] of Porciuncula." and that the map was in error.<ref name="Pool"></ref> | |||

| ===Early pueblo=== | |||

| The town grew as soldiers and other settlers came into town and stayed. In 1784 a chapel was built on the ]. The original Plaza was located a block north and west of the present one — its southeast corner being roughly where the northwesternmost point of the present plaza is, at the former intersection of ]. It was also oriented diagonally, i.e. at precisely a 90-degree angle to the four compass points.<ref name="CaliforniaCalifornia1893">{{cite book|author1=Historical Society of Southern California|author2=Los Angeles County Pioneers of Southern California|title=The Quarterly|publisher=Historical Society of Southern California|url=https://archive.org/details/quarterly00unkngoog|edition=Public domain|year=1893|pages=–}}</ref> | |||

| The ''pobladores'' were given title to their land two years later. By 1800, there were 29 buildings that surrounded the Plaza, flat-roofed, one-story adobe buildings with thatched roofs made of tule.<ref name="layne">Layne, James Gregg. 1935. ''Annals of Los Angeles 1769–1861, Special Publication No. 9''. San Francisco: California Historical Society. p. 30.</ref> By 1821, Los Angeles had grown into a self-sustaining farming community, the largest in Southern California. | |||

| Each settler received four rectangles of land, ''suertes'', for farming, two irrigated plots and two dry ones.<ref name="plaza" /><ref name="crouch">Crouch, Dora P., Daniel J. Garr, and Axel I Mundigo. 1982. ''Spanish City Planning in North America''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.</ref> When the settlers arrived, the Los Angeles floodplain was heavily wooded with willows and oaks. The ] flowed all year. Wildlife was plentiful, including deer and black bears, and even an occasional ]. There were abundant wetlands and swamps. ] and ] swam the rivers. | |||

| The first settlers built a ] leading from the river through the middle of town and into the farmlands. Indians were employed to haul fresh drinking water from a special pool farther upstream. The city was first known as a producer of fine wine grapes. The raising of cattle and the commerce in tallow and hides came later.<ref name="river">Gumprecht, Blake. 1999. ''The Los Angeles River: It's Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth.'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.</ref> | |||

| Because of the great economic potential for Los Angeles, the demand for Indian labor grew rapidly. Yaanga began attracting Indians from the Channel Islands and as far away as ] and ]. The village began to look like a refugee camp. Unlike the missions, the ''pobladores'' paid Indians for their labor. In exchange for their work as farm workers, ''vaqueros'', ditch diggers, water haulers, and domestic help; they were paid in clothing and other goods as well as cash and alcohol. The ''pobladores'' bartered with them for prized sea-otter and seal pelts, sieves, trays, baskets, mats, and other woven goods. This commerce greatly contributed to the economic success of the town and the attraction of other Indians to the city.<ref name="interaction" /> | |||

| During the 1780s, ] became the object of an Indian revolt. The mission had expropriated all the suitable farming land; the Indians found themselves abused and forced to work on lands that they once owned. A young Indian healer, ], began touring the area, preaching against the injustices suffered by her people. She won over four ''rancherías'' and led them in an attack on the mission at San Gabriel. The soldiers were able to defend the mission, and arrested 17, including Toypurina.<ref name="revolt">Estrada, William David. 2005. "Toypurina, Leader of the Tongva People", Oxford Enchyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States, ed. Suzanne Oboler and Deena J. Gonzalez, vol. 4, pp. 242–243. New York: Oxford University Press.</ref> | |||

| In 1787, Governor ] outlined his "Instructions for the Corporal Guard of the Pueblo of Los Angeles." The instructions included rules for employing Indians, not using corporal punishment, and protecting the Indian ''rancherías''. As a result, Indians found themselves with more freedom to choose between the benefits of the missions and the pueblo-associated ''rancherías''.<ref name="mason">Mason, William Marvin. 1975. "Fages' Code of Conduct Toward Indians, 1787." ''Journal of California Anthropology'', 2:1, pp. 90–100.</ref> | |||

| In 1795, Sergeant Pablo Cota led an expedition from the ] through the ] and into the ]. His party visited the'' rancho'' of Francisco Reyes. They found the local Indians hard at work as ''vaqueros'' and caring for crops. Padre Vincente de Santa Maria was traveling with the party and made these observations: | |||

| <blockquote>All of pagandom (Indians) is fond of the pueblo of Los Angeles, of the rancho of Reyes, and of the ditches (water system). Here we see nothing but pagans, clad in shoes, with sombreros and blankets, and serving as muleteers to the settlers and rancheros, so that if it were not for the gentiles there were neither pueblos nor ranches. These pagan Indians care neither for the missions nor for the missionaries.<ref name="forbes">Forbes, Jack D. 1966. ''The Tongva of Tujunga to 1801'', Archeological Survey Annual Report, appendix 2. Los Angeles: University of California.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Not only economic ties but also marriage drew many Indians into the life of the pueblo. In 1784, only three years after the founding, the first recorded marriages in Los Angeles took place. The two sons of settler Basilio Rosas, Maximo and José Carlos, married two young Indian women, María Antonia and María Dolores.<ref name="mason2">Mason, William Marvin. 1978. "The Garrisons of San Diego Presidio: 1770–1794." Journal of San Diego History, 24, no. 4:411.</ref> | |||

| The construction on the ] took place between 1818 and 1822, much of it with Indian labor. The new church completed Governor de Neve's planned transition of authority from mission to pueblo. The ''angelinos'' no longer had to make the bumpy {{convert|11|mi|km|adj=on}} ride to Sunday Mass at Mission San Gabriel. | |||

| In 1811, the population of Los Angeles had increased to more than five hundred persons, of which ninety-one were heads of families.<ref>{{cite book |title= Yesterday's Los Angeles: Seemann's Historic Cities Series No. 26|last=Dash |first=Norman| authorlink=Norman Dash|year= 1976 |publisher=E.A. Seemann Publishing Inc., Miami, Florida |page=16}}</ref> | |||

| In 1820, the route of ] was established from Los Angeles, over the mountains to the north and up the west side of the ] to the east side of ]. | |||

| ==Mexican era: 1821-1848== | |||

| Mexico's independence from Spain on September 28, 1821 was celebrated with great festivity throughout Alta California. No longer subjects of the king, people were now ''ciudadanos'', citizens with rights under the law. In the plazas of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and other settlements, people swore allegiance to the new government, the Spanish flag was lowered, and the flag of independent Mexico raised.<ref name="history" /> | |||

| Independence brought other advantages, including economic growth. There was a corresponding increase in population as more Indians were assimilated and others arrived from America, Europe, and other parts of Mexico. Before 1820, there were just 650 people in the pueblo. By 1841, the population nearly tripled to 1,680.<ref name="growth">Northrop, Marie E. ed. 1960. "the Los Angeles Padron of 1844 as Copied from the Los Angeles City Archives." ''Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly'', 42, no. 4, December, 360–417.</ref> | |||

| ===Secularization of the missions=== | |||

| During the rest of the 1820s, the agriculture and cattle ranching expanded as did the trade in hides and tallow. The new church was completed, and the political life of the city developed. Los Angeles was separated from Santa Barbara administration. The system of ditches which provided water from the river was rebuilt. In 1827 ] and John Rice opened the first ] in the pueblo, soon followed by J. D. Leandry.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Newmark |first1=Marco |title=Pioneer Merchants of Los Angeles |journal=Historical Society of Southern California |date=1942 |page=77 }}</ref> Trade and commerce further increased with the ] by the ] in 1833. Extensive mission lands suddenly became available to government officials, ranchers, and land speculators. The governor made more than 800 land grants during this period, including a ] in 1839 to ] which was later developed as the westside of Los Angeles.<ref name="Map of Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica, Santa Monica: Calendar of Events in the Making of a City, 1875-1950.">{{Cite web |url=http://digital.smpl.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/SMIA/id/2611/rec/5 |title=Archived copy |access-date=2013-10-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131012050400/http://digital.smpl.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/SMIA/id/2611/rec/5 |archive-date=2013-10-12 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Much of this progress, however, bypassed the Indians of the traditional villages who were not assimilated into the ''mestizo'' culture. Being regarded as minors who could not think for themselves, they were increasingly marginalized and relieved of their land titles, often by being drawn into debt or alcohol.<ref name="titles">Gonzalez, Michael J. 1998. "The Child of the Wilderness Weeps for the Father of Our Country: The Indian and the Politics of Church and State in Provincial Southern California", in ''Contested Eden: California Before the Gold Rush'', ed. Ramón A. Gutiérrez and Richard J. Orsi. Berkeley: University of California Press.</ref> | |||

| In 1834, ] was married to Maria Ignacio Alvarado in the Plaza church. It was attended by the entire population of the pueblo, 800 people, plus hundreds from elsewhere in Alta California. In 1835, the Mexican Congress declared Los Angeles a city, making it the official capital of Alta California. It was now the region's leading city. | |||

| The same period also saw the arrival of many foreigners from the United States and Europe. They played a pivotal role in the U.S. takeover. Early California settler ] included several historical figures in his recollection of people he knew in March, 1845. | |||

| <blockquote>"It then had probably two hundred and fifty people, of whom I recall Don ], ], Captain Alexander Bell, ], ],<ref>Iris Higbie Wilson: "Lemuel Carpenter" in ''The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West'', LeRoy R. Hafen, ed., The Arthur H. Clark Co., Glendale, California, 1972, pp. 33–40.</ref><ref>Hubert Howe Bancroft: ''California Pioneer Register and Index 1542–1848'', Regional Publishing Co., Baltimore, Maryland, 1964, p. 82.</ref><ref>Charles Russell Quinn: ''History of Downey, The Life Story of a Pioneer Community, and of the Man who Founded it – California Governor John Gately Downey – From Covered Wagon to the Space Shuttle'', Elena Quinn, Downey, California, 1973, pp. 12, 20–22, 32, 104–105, et al.</ref> ]; also of Mexicans, ] (governor), Don ], and others."<ref>John Bidwell: "First-Person Narratives of California's Early Years, 1849–1900", Library of Congress Historical Collections, "American Memory": John Bidwell (Pioneer of '41): ''Life in California Before the Gold Discovery'', from the collection "California As I Saw It."</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Upon arriving in Los Angeles in 1831, ] bought {{convert|104|acre|km2}} of land located between the original Pueblo and the banks of the ]. He planted a vineyard and prepared to make wine.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| | last = Gaughan | |||

| | first = Tim | |||

| | title = Where the valley met the vine: The Mexican period | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | publisher = Lee Enterprises, Inc. | |||

| | location = Napa, California | |||

| | date = June 19, 2009 | |||

| | url = http://napavalleyregister.com/lifestyles/food-and-cooking/wine/where-the-valley-met-the-vine-the-mexican-period/article_2ae8cae7-9655-5f01-9391-9278fed3b9b3.html | |||

| | access-date = September 30, 2011}}</ref> He named his property ''El Aliso'' after the centuries-old tree found near the entrance. The grapes available at the time, of the ], were brought to Alta California by the ] Brothers at the end of the 18th century. They grew well and yielded large quantities of wine, but Jean-Louis Vignes was not satisfied with the results. Therefore, he decided to import better vines from Bordeaux: ], ], and ]. In 1840, Jean-Louis Vignes made the first recorded shipment of California wine. The Los Angeles market was too small for his production, and he loaded a shipment on the Monsoon, bound for Northern California.<ref>Foucrier, Annick. Op. Cit. Page 53</ref> By 1842, he made regular shipments to ], ] and San Francisco. By 1849, ''El Aliso'', was the most extensive vineyard in California. Vignes owned over 40,000 vines and produced 150,000 bottles, or 1,000 barrels, per year.<ref>McGroarty, John Steven. ''History of Los Angeles County''. The American Historical Society. Chicago and New York 1923. Page 31</ref> | |||

| ===Invasion by United States=== | |||

| In May 1846, the ] started. Because of Mexico's inability to defend its northern territories, California was exposed to invasion. On August 13, 1846, Commodore ], accompanied by ], seized the town; Governor Pico had fled to Mexico. From Stockton and Frémont until late 1849, all of ]. After three weeks of occupation, Stockton left, leaving Lieutenant ] in charge. Subsequent dissatisfaction with Gillespie and his troops led to an uprising. A force of 300 locals drove the Americans out, ending the first phase of the ].<ref name="history" /> Further small skirmishes took place. Stockton regrouped in San Diego and marched north with six hundred troops while Frémont marched south from Monterey with 400 troops. After a few skirmishes outside the city, the two forces entered Los Angeles, this time without bloodshed. ] was in charge; he signed the so-called ] (it was not a treaty) on 13 January 1847, ending the California phase of the Mexican–American War. The ], signed on 2 February 1848, ended the war and ceded California to the U.S.<ref name="history" /> | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{ref list}} | |||

Revision as of 20:19, 9 April 2021

| Old Los Angeles | |

|---|---|

Legend Legend

|

The modern History of Los Angeles began in 1781 when 44 settlers from New Spain established a permanent settlement in what is now Downtown Los Angeles, as instructed by Spanish Governor of Las Californias Felipe de Neve and authorized by Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli. After sovereignty changed from Mexico to the U.S. in 1848, great changes came from the completion of the Santa Fe railroad line from Chicago to Los Angeles in 1885. “Overlanders” flooded in, mostly White Protestants from the Lower Midwest and South.

Los Angeles had a strong economic base in farming, oil, tourism, real estate and movies. It grew rapidly with many suburban areas inside and outside the city limits. Its motion picture industry made the city world-famous, and World War II brought new industry, especially high-tech aircraft construction. Politically the city was moderately conservative, with a weak labor union sector.

Since the 1960s, growth has slowed—and traffic delays have become infamous. Los Angeles was a pioneer in freeway development as the public transit system deteriorated. New arrivals, especially from Mexico and Asia, have transformed the demographic base since the 1960s. Old industries have declined, including farming, oil, military and aircraft, but tourism, entertainment and high-tech remain strong.

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of California |

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

Early history

By 3000 B.C., the area was occupied by the Hokan-speaking people of the Milling Stone Period who fished, hunted sea mammals, and gathered wild seeds. They were later replaced by migrants — possibly fleeing drought in the Great Basin — who spoke a Uto-Aztecan language called Tongva. The Tongva people called the Los Angeles region Yaa in Tongva.

By the 1700s A.D., there were 250,000 to 300,000 native people in California and 5,000 in the Los Angeles basin. The land occupied and used by the Tongva covered about 4,000 square miles (10,000 km). It included the enormous floodplain drained by the Los Angeles and San Gabriel rivers and the southern Channel Islands, including the Santa Barbara, San Clemente, Santa Catalina, and San Nicolas Islands. They were part of a sophisticated group of trading partners that included the Chumash to the west, the Cahuilla and Mojave to the east, and the Juaneños and Luiseños to the south. Their trade extended to the Colorado River and included slavery.

The lives of the Tongva were governed by a set of religious and cultural practices that included belief in creative supernatural forces. They worshipped Chinigchinix, a creator god, and Chukit, a female virgin god. Their Great Morning Ceremony was based on a belief in the afterlife. In a purification ritual, they drank tolguache, a hallucinogenic made from jimson weed and salt water. Their language was called Kizh or Kij, and they practiced cremation.

Generations before the arrival of the Europeans, the Tongva had identified and lived in the best sites for human occupation. The survival and success of Los Angeles depended greatly on the presence of a nearby and prosperous Tongva village called Yaanga. Its residents provided the colonists with seafood, fish, bowls, pelts, and baskets. For pay, they dug ditches, hauled water, and provided domestic help. They often intermarried with the Mexican colonists.

Spanish era: 1769-1821

Main articles: Pueblo de Los Angeles and Los Angeles Pobladores

In 1542 and 1602, the first Europeans to visit the region were Captain Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo and Captain Sebastián Vizcaíno. The first permanent non-native presence began when the Portolá expedition arrived on August 2, 1769.

Plans for the pueblo

Although Los Angeles was a town that was founded by Mexican families from Sonora, it was the Spanish governor of California who named the settlement.

In 1777, Governor Felipe de Neve toured Alta California and decided to establish civic pueblos for the support of the military presidios. The new pueblos reduced the secular power of the missions by reducing the dependency of the military on them. At the same time, they promoted the development of industry and agriculture.

Governor de Neve identified Santa Barbara, San Jose, and Los Angeles as sites for his new pueblos. His plans for them closely followed a set of Spanish city-planning laws contained in the Laws of the Indies promulgated by King Philip II in 1573. Those laws were responsible for laying the foundations of the largest cities in the region at the time, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Tucson, San Antonio, Sonoma, Monterey, Santa Fe, and Laredo.

The Spanish system called for an open central plaza, surrounded by a fortified church, administrative buildings, and streets laid out in a grid, defining rectangles of limited size to be used for farming (suertes) and residences (solares).

It was in accordance with such precise planning—specified in the Law of the Indies—that Governor de Neve founded the pueblo of San Jose de Guadalupe, California's first municipality, on the great plain of Santa Clara on 29 November 1777.

Pobladores

Main article: Los Angeles PobladoresThe Pobladores ("settlers") is the name given to the 44 original settlers, 22 adults and 22 children from Sonora, who founded the town. Of the 44, 20 of the settlers were of African American or Native American descent, making LA one of the few cities in the United States with such a diverse beginning. In December 1777, Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa and Commandant General Teodoro de Croix gave approval for the founding of a civic municipality at Los Angeles and a new presidio at Santa Barbara.

Croix put the California lieutenant governor Fernando Rivera y Moncada in charge of recruiting colonists for the new settlements. He was originally instructed to recruit 55 soldiers, 22 settlers with families and 1,000 head of livestock that included horses for the military. After an exhausting search that took him to Mazatlán, Rosario, and Durango, Rivera y Moncada only recruited 12 settlers and 45 soldiers. Like the people of most towns in New Spain they were a mix of Indian and Spanish backgrounds. The Quechan Revolt killed 95 settlers and soldiers, including Rivera y Moncada.

In his Reglamento, the newly baptized Indians were no longer to reside in the mission but live in their traditional rancherías (villages). Governor de Neve's new plans for the Indians' role in his new town drew instant disapproval from the mission priests.

Zúñiga's party arrived at the mission on 18 July 1781. Because they had arrived with smallpox, they immediately were quarantined a short distance away from the mission. Members of the other party arrived at different times by August. They made their way to Los Angeles and probably received their land before September.

Founding

The official date for the founding of the city is September 4, 1781. The families had arrived from New Spain earlier in 1781, in two groups, and some of them had most likely been working on their assigned plots of land since the early summer.

The name first given to the settlement is debated. Historian Doyce B. Nunis has said that the Spanish named it "El Pueblo de la Reina de los Angeles" ("The Town of the Queen of the Angels"). For proof, he pointed to a map dated 1785, where that phrase was used. Frank Weber, the diocesan archivist, replied, however, that the name given by the founders was "El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de Porciuncula", or "the town of Our Lady of the Angels of Porciuncula." and that the map was in error.

Early pueblo

The town grew as soldiers and other settlers came into town and stayed. In 1784 a chapel was built on the original Plaza. The original Plaza was located a block north and west of the present one — its southeast corner being roughly where the northwesternmost point of the present plaza is, at the former intersection of Upper Main and Marchessault streets. It was also oriented diagonally, i.e. at precisely a 90-degree angle to the four compass points. The pobladores were given title to their land two years later. By 1800, there were 29 buildings that surrounded the Plaza, flat-roofed, one-story adobe buildings with thatched roofs made of tule. By 1821, Los Angeles had grown into a self-sustaining farming community, the largest in Southern California.

Each settler received four rectangles of land, suertes, for farming, two irrigated plots and two dry ones. When the settlers arrived, the Los Angeles floodplain was heavily wooded with willows and oaks. The Los Angeles River flowed all year. Wildlife was plentiful, including deer and black bears, and even an occasional grizzly bear. There were abundant wetlands and swamps. Steelhead trout and salmon swam the rivers.

The first settlers built a water system consisting of ditches (zanjas) leading from the river through the middle of town and into the farmlands. Indians were employed to haul fresh drinking water from a special pool farther upstream. The city was first known as a producer of fine wine grapes. The raising of cattle and the commerce in tallow and hides came later.

Because of the great economic potential for Los Angeles, the demand for Indian labor grew rapidly. Yaanga began attracting Indians from the Channel Islands and as far away as San Diego and San Luis Obispo. The village began to look like a refugee camp. Unlike the missions, the pobladores paid Indians for their labor. In exchange for their work as farm workers, vaqueros, ditch diggers, water haulers, and domestic help; they were paid in clothing and other goods as well as cash and alcohol. The pobladores bartered with them for prized sea-otter and seal pelts, sieves, trays, baskets, mats, and other woven goods. This commerce greatly contributed to the economic success of the town and the attraction of other Indians to the city.

During the 1780s, San Gabriel Mission became the object of an Indian revolt. The mission had expropriated all the suitable farming land; the Indians found themselves abused and forced to work on lands that they once owned. A young Indian healer, Toypurina, began touring the area, preaching against the injustices suffered by her people. She won over four rancherías and led them in an attack on the mission at San Gabriel. The soldiers were able to defend the mission, and arrested 17, including Toypurina.

In 1787, Governor Pedro Fages outlined his "Instructions for the Corporal Guard of the Pueblo of Los Angeles." The instructions included rules for employing Indians, not using corporal punishment, and protecting the Indian rancherías. As a result, Indians found themselves with more freedom to choose between the benefits of the missions and the pueblo-associated rancherías.

In 1795, Sergeant Pablo Cota led an expedition from the Simi Valley through the Conejo-Calabasas region and into the San Fernando Valley. His party visited the rancho of Francisco Reyes. They found the local Indians hard at work as vaqueros and caring for crops. Padre Vincente de Santa Maria was traveling with the party and made these observations:

All of pagandom (Indians) is fond of the pueblo of Los Angeles, of the rancho of Reyes, and of the ditches (water system). Here we see nothing but pagans, clad in shoes, with sombreros and blankets, and serving as muleteers to the settlers and rancheros, so that if it were not for the gentiles there were neither pueblos nor ranches. These pagan Indians care neither for the missions nor for the missionaries.

Not only economic ties but also marriage drew many Indians into the life of the pueblo. In 1784, only three years after the founding, the first recorded marriages in Los Angeles took place. The two sons of settler Basilio Rosas, Maximo and José Carlos, married two young Indian women, María Antonia and María Dolores.

The construction on the Plaza of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Los Ángeles took place between 1818 and 1822, much of it with Indian labor. The new church completed Governor de Neve's planned transition of authority from mission to pueblo. The angelinos no longer had to make the bumpy 11-mile (18 km) ride to Sunday Mass at Mission San Gabriel.

In 1811, the population of Los Angeles had increased to more than five hundred persons, of which ninety-one were heads of families.

In 1820, the route of El Camino Viejo was established from Los Angeles, over the mountains to the north and up the west side of the San Joaquin Valley to the east side of San Francisco Bay.

Mexican era: 1821-1848

Mexico's independence from Spain on September 28, 1821 was celebrated with great festivity throughout Alta California. No longer subjects of the king, people were now ciudadanos, citizens with rights under the law. In the plazas of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and other settlements, people swore allegiance to the new government, the Spanish flag was lowered, and the flag of independent Mexico raised.

Independence brought other advantages, including economic growth. There was a corresponding increase in population as more Indians were assimilated and others arrived from America, Europe, and other parts of Mexico. Before 1820, there were just 650 people in the pueblo. By 1841, the population nearly tripled to 1,680.

Secularization of the missions

During the rest of the 1820s, the agriculture and cattle ranching expanded as did the trade in hides and tallow. The new church was completed, and the political life of the city developed. Los Angeles was separated from Santa Barbara administration. The system of ditches which provided water from the river was rebuilt. In 1827 Jonathan Temple and John Rice opened the first general store in the pueblo, soon followed by J. D. Leandry. Trade and commerce further increased with the secularization of the California missions by the Mexican Congress in 1833. Extensive mission lands suddenly became available to government officials, ranchers, and land speculators. The governor made more than 800 land grants during this period, including a grant of over 33,000-acres in 1839 to Francisco Sepúlveda which was later developed as the westside of Los Angeles.

Much of this progress, however, bypassed the Indians of the traditional villages who were not assimilated into the mestizo culture. Being regarded as minors who could not think for themselves, they were increasingly marginalized and relieved of their land titles, often by being drawn into debt or alcohol.

In 1834, Governor Pico was married to Maria Ignacio Alvarado in the Plaza church. It was attended by the entire population of the pueblo, 800 people, plus hundreds from elsewhere in Alta California. In 1835, the Mexican Congress declared Los Angeles a city, making it the official capital of Alta California. It was now the region's leading city.

The same period also saw the arrival of many foreigners from the United States and Europe. They played a pivotal role in the U.S. takeover. Early California settler John Bidwell included several historical figures in his recollection of people he knew in March, 1845.

"It then had probably two hundred and fifty people, of whom I recall Don Abel Stearns, John Temple, Captain Alexander Bell, William Wolfskill, Lemuel Carpenter, David W. Alexander; also of Mexicans, Pio Pico (governor), Don Juan Bandini, and others."

Upon arriving in Los Angeles in 1831, Jean-Louis Vignes bought 104 acres (0.42 km) of land located between the original Pueblo and the banks of the Los Angeles River. He planted a vineyard and prepared to make wine. He named his property El Aliso after the centuries-old tree found near the entrance. The grapes available at the time, of the Mission variety, were brought to Alta California by the Franciscan Brothers at the end of the 18th century. They grew well and yielded large quantities of wine, but Jean-Louis Vignes was not satisfied with the results. Therefore, he decided to import better vines from Bordeaux: Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Sauvignon blanc. In 1840, Jean-Louis Vignes made the first recorded shipment of California wine. The Los Angeles market was too small for his production, and he loaded a shipment on the Monsoon, bound for Northern California. By 1842, he made regular shipments to Santa Barbara, Monterey and San Francisco. By 1849, El Aliso, was the most extensive vineyard in California. Vignes owned over 40,000 vines and produced 150,000 bottles, or 1,000 barrels, per year.

Invasion by United States

In May 1846, the Mexican–American War started. Because of Mexico's inability to defend its northern territories, California was exposed to invasion. On August 13, 1846, Commodore Robert F. Stockton, accompanied by John C. Frémont, seized the town; Governor Pico had fled to Mexico. From Stockton and Frémont until late 1849, all of California had a military governor. After three weeks of occupation, Stockton left, leaving Lieutenant Archibald H. Gillespie in charge. Subsequent dissatisfaction with Gillespie and his troops led to an uprising. A force of 300 locals drove the Americans out, ending the first phase of the Battle of Los Angeles. Further small skirmishes took place. Stockton regrouped in San Diego and marched north with six hundred troops while Frémont marched south from Monterey with 400 troops. After a few skirmishes outside the city, the two forces entered Los Angeles, this time without bloodshed. Andrés Pico was in charge; he signed the so-called Treaty of Cahuenga (it was not a treaty) on 13 January 1847, ending the California phase of the Mexican–American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on 2 February 1848, ended the war and ceded California to the U.S.

References

- “The Overland Migration”

- “News by the Goliah”

- “From the Texan Border”

- “Breckinridge to Visit California.”

- “Overland Mail—Southern Route.“

- “His Nose was Scratched.”

- Munro, Pamela, et al. Yaara' Shiraaw'ax 'Eyooshiraaw'a. Now You're Speaking Our Language: Gabrielino/Tongva/Fernandeño. Lulu.com: 2008.

- Smith, Gerald A. and James Clifford. 1965. Indian Slave Trade Along the Mojave Trail. San Bernardino California: San Bernardino County Museum.

- Johnson, Bernice Eastman. 1962. California's Gabrielino Indians. Highland Park, California: Southwest Museum Papers.

- Bosca, Gerónimo. "Chinigchinish: An Historical Account of the Origins, Customs, and Traditions of the Indians of Alta California", in Life in California, trans. Alfred Robinson. Santa Barbara: Peregrine.

- Miller, Bruce. 1991. The Gabrielino. Los Osos, California: Sand River Press.

- ^ Kealhofer, 1991. Cultural Interaction During the Spanish Colonial Period. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1991.

- McCawley, William. 1996. The First Angelinos: The Indians of Los Angeles. Banning, California: Malki Museum Press and Ballena Press Cooperative. pp. 2–7

- ^ Estrada, William David. 2008. The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Low, Setha M. 2000. On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Cruz, Gilberto R. 1988. Let There Be Towns: Spanish Municipal Origins in the American Southwest, 1610–1810. College Station, Texas: A&M University Press.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. 1886. History of California. 7 volumes. San Francisco: History Company.

- ^ Kelsey, Harry. 1976. "A New Look at the Founding of Los Angeles." Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly. 55:4, Winter. pp. 326–339.

- "The founder of the city of Los Angeles". www.turismobailen.es. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Ríos-Bustamante, Antonio. Mexican Los Ángeles: A Narrative and Pictoral History, Nuestra Historia Series, Monograph No. 1. (Encino: Floricanto Press, 1992), 50–53. OCLC 228665328.

- Bob Pool, "City of Angels' First Name Still Bedevils Historians." Los Angeles Times (March 26, 2005).

- Historical Society of Southern California; Los Angeles County Pioneers of Southern California (1893). The Quarterly (Public domain ed.). Historical Society of Southern California. pp. 41–.

- Layne, James Gregg. 1935. Annals of Los Angeles 1769–1861, Special Publication No. 9. San Francisco: California Historical Society. p. 30.

- Crouch, Dora P., Daniel J. Garr, and Axel I Mundigo. 1982. Spanish City Planning in North America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Gumprecht, Blake. 1999. The Los Angeles River: It's Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Estrada, William David. 2005. "Toypurina, Leader of the Tongva People", Oxford Enchyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States, ed. Suzanne Oboler and Deena J. Gonzalez, vol. 4, pp. 242–243. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mason, William Marvin. 1975. "Fages' Code of Conduct Toward Indians, 1787." Journal of California Anthropology, 2:1, pp. 90–100.

- Forbes, Jack D. 1966. The Tongva of Tujunga to 1801, Archeological Survey Annual Report, appendix 2. Los Angeles: University of California.

- Mason, William Marvin. 1978. "The Garrisons of San Diego Presidio: 1770–1794." Journal of San Diego History, 24, no. 4:411.

- Dash, Norman (1976). Yesterday's Los Angeles: Seemann's Historic Cities Series No. 26. E.A. Seemann Publishing Inc., Miami, Florida. p. 16.

- Northrop, Marie E. ed. 1960. "the Los Angeles Padron of 1844 as Copied from the Los Angeles City Archives." Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, 42, no. 4, December, 360–417.

- Newmark, Marco (1942). "Pioneer Merchants of Los Angeles". Historical Society of Southern California: 77.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Gonzalez, Michael J. 1998. "The Child of the Wilderness Weeps for the Father of Our Country: The Indian and the Politics of Church and State in Provincial Southern California", in Contested Eden: California Before the Gold Rush, ed. Ramón A. Gutiérrez and Richard J. Orsi. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Iris Higbie Wilson: "Lemuel Carpenter" in The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed., The Arthur H. Clark Co., Glendale, California, 1972, pp. 33–40.

- Hubert Howe Bancroft: California Pioneer Register and Index 1542–1848, Regional Publishing Co., Baltimore, Maryland, 1964, p. 82.

- Charles Russell Quinn: History of Downey, The Life Story of a Pioneer Community, and of the Man who Founded it – California Governor John Gately Downey – From Covered Wagon to the Space Shuttle, Elena Quinn, Downey, California, 1973, pp. 12, 20–22, 32, 104–105, et al.

- John Bidwell: "First-Person Narratives of California's Early Years, 1849–1900", Library of Congress Historical Collections, "American Memory": John Bidwell (Pioneer of '41): Life in California Before the Gold Discovery, from the collection "California As I Saw It."

- Gaughan, Tim (June 19, 2009). "Where the valley met the vine: The Mexican period". Napa Valley Register. Napa, California: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Foucrier, Annick. Op. Cit. Page 53

- McGroarty, John Steven. History of Los Angeles County. The American Historical Society. Chicago and New York 1923. Page 31