| Revision as of 21:21, 17 April 2013 view sourceSPECIFICO (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users35,511 edits Please do not edit war. Seek consensus on talk. Restoring valid sourced content.← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:51, 17 April 2013 view source Antiquax (talk | contribs)77 edits The paper was published Nov 2008. Ccy went live 3rd Jan 2009Next edit → | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

| --> | --> | ||

| '''Bitcoin''' ('''BTC''') is an ] which was first described in a |

'''Bitcoin''' ('''BTC''') is an ] which was first described in a 2008 paper by ]ous ] Satoshi Nakamoto, who called it an anonymous, ], electronic payments system. Bitcoin creation and transfer is based on an ] ] and is not managed by any central authority. The creation of new bitcoins is automated and may be accomplished by ], called ''bitcoin miners'' that run on an internet-based network and confirm bitcoin transactions by adding codes to a decentralized log, which is updated and archived periodically.<ref name=UCPaper /> Each bitcoin is subdivided into 100 million smaller units called satoshis, defined by eight decimal places.<ref name="satoshi unit">{{cite web|title=Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency|url=http://www.dailytech.com/Cracking+the+Bitcoin+Digging+Into+a+131M+USD+Virtual+Currency/article21878.htm|publisher=Daily Tech|date=12 June 2011|accessdate=30 September 2012}}</ref> | ||

| Bitcoins can be transferred through a ] or ] without an intermediate financial institution.<ref>{{cite journal|last1= Hough |first1= Jack |date=3 June 2011 |title= The Currency That's Up 200,000% |journal= ] |volume= |issue= |pages= |publisher= Dow Jones & Company |url= http://www.smartmoney.com/invest/stocks/the-currency-thats-up-200000-1307029053200/ |accessdate= 18 February 2013 }}</ref> Interested parties can authenticate the ownership of bitcoin balances by using dedicated ] (the ''bitcoin miners'') to authenticate the bitcoin transaction log using a ] scheme. Each 10-minute portion or "block" of the transaction log also allows for a predetermined number of new bitcoins to be awarded to miners based on computational data added to the log and confirmed by other miners. The creation of a new bitcoin is thus a special case of a transaction in which the new bitcoin deemed issued in exchange for solving a computationally intensive encryption problem.<ref name=UCPaper /> The number of newly created bitcoins per period depends on how long the network has been running. Currently, 25 new bitcoins are generated with every 10-minute block. This will be halved to 12.5 BTC during the year 2017 and halved continuously every 4 years after until a hard limit of 21 million bitcoins is reached during the year 2140.<ref name=whitepaper /><ref name=Wired:RFB /> | Bitcoins can be transferred through a ] or ] without an intermediate financial institution.<ref>{{cite journal|last1= Hough |first1= Jack |date=3 June 2011 |title= The Currency That's Up 200,000% |journal= ] |volume= |issue= |pages= |publisher= Dow Jones & Company |url= http://www.smartmoney.com/invest/stocks/the-currency-thats-up-200000-1307029053200/ |accessdate= 18 February 2013 }}</ref> Interested parties can authenticate the ownership of bitcoin balances by using dedicated ] (the ''bitcoin miners'') to authenticate the bitcoin transaction log using a ] scheme. Each 10-minute portion or "block" of the transaction log also allows for a predetermined number of new bitcoins to be awarded to miners based on computational data added to the log and confirmed by other miners. The creation of a new bitcoin is thus a special case of a transaction in which the new bitcoin deemed issued in exchange for solving a computationally intensive encryption problem.<ref name=UCPaper /> The number of newly created bitcoins per period depends on how long the network has been running. Currently, 25 new bitcoins are generated with every 10-minute block. This will be halved to 12.5 BTC during the year 2017 and halved continuously every 4 years after until a hard limit of 21 million bitcoins is reached during the year 2140.<ref name=whitepaper /><ref name=Wired:RFB /> | ||

Revision as of 21:51, 17 April 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

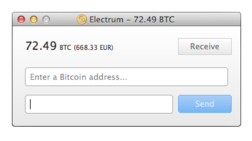

A digital bitcoin wallet A digital bitcoin wallet | |

| ISO 4217 | |

|---|---|

| Unit | |

| Symbol | BTC, |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| .001 | mBTC (millicoin) |

| .000001 | μBTC (microcoin) |

| .00000001 | satoshi |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 3 January 2009Bitcoin Genesis Block |

| User(s) | International |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | The majority of the bitcoin peer-to-peer network regulates transactions and balances. |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | Limited release |

| Source | Total BTC in Circulation |

| Method | The rate of inflation will be halved every 4 years until there are 21 million BTC |

Bitcoin (BTC) is an digital currency which was first described in a 2008 paper by pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto, who called it an anonymous, peer-to-peer, electronic payments system. Bitcoin creation and transfer is based on an open source encryption protocol and is not managed by any central authority. The creation of new bitcoins is automated and may be accomplished by servers, called bitcoin miners that run on an internet-based network and confirm bitcoin transactions by adding codes to a decentralized log, which is updated and archived periodically. Each bitcoin is subdivided into 100 million smaller units called satoshis, defined by eight decimal places.

Bitcoins can be transferred through a computer or smartphone without an intermediate financial institution. Interested parties can authenticate the ownership of bitcoin balances by using dedicated servers (the bitcoin miners) to authenticate the bitcoin transaction log using a public-key encryption scheme. Each 10-minute portion or "block" of the transaction log also allows for a predetermined number of new bitcoins to be awarded to miners based on computational data added to the log and confirmed by other miners. The creation of a new bitcoin is thus a special case of a transaction in which the new bitcoin deemed issued in exchange for solving a computationally intensive encryption problem. The number of newly created bitcoins per period depends on how long the network has been running. Currently, 25 new bitcoins are generated with every 10-minute block. This will be halved to 12.5 BTC during the year 2017 and halved continuously every 4 years after until a hard limit of 21 million bitcoins is reached during the year 2140.

Bitcoin is accepted in trade by various merchants and individuals in many parts of the world. Although bitcoin was initially promoted as a digital currency, many commentators currently reject that claim due to bitcoin's volatile market value, relatively inflexible supply, and minimal use in trade.

Transactions

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. The specific problem is: This section contains unsourced, incomplete, and confusing content. Please help improve this article if you can. (April 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Bitcoins can be sent and received through various websites and apps after being bought on an exchange.

Addresses

Based on digital signatures, payments are made to bitcoin "addresses" or "public keys": human-readable strings of numbers and letters around 33 characters in length, always beginning with the digit 1 or 3, as in the example of 175tWpb8K1S7NmH4Zx6rewF9WQrcZv245W.

Users obtain new bitcoin addresses as necessary; these are stored in a wallet file with links to cryptographic passwords or "private keys" that enable access to and transfer of bitcoins. A file or "wallet" containing bitcoin addresses is usually encrypted with an additional password.

Confirmation

| This article is missing information about why bitcoin users would voluntarily pay a transaction fee for a peer-to-peer transfer? . Please expand the article to include this informationto include this information or by making an edit request. Further details may exist on the talk page. (April 2013) |

The network's software confirms transactions when it records them in the transaction log or "blockchain" stored across the peer-to-peer network every 10-minutes. Confirmation of future transaction records makes the ones before it increasingly permanent. After six confirmed records or "blocks" (usually one hour), a transaction is usually considered confirmed beyond reasonable doubt.

Initiators of a bitcoin transaction may voluntarily pay a transaction fee for the confirmation of these records. Any fees are collected by the operators of bitcoin servers -- often called nodes or "bitcoin miners". However, transaction fees may not cover the cost of electrical power required to operate a bitcoin miner. As a result the network server operators often rely on "mined" bitcoins as their only significant revenue.

Banknotes and coins

Various vendors offer banknotes and coins denominated in bitcoins; a bitcoin private key is sold as part of a coin or banknote. Usually, a seal has to be broken to access the key, while the receiving address remains visible on the outside so that the balance can be verified.

A 1-BTC Casascius Coin was shown in the British Museum in London to represent bitcoin.

History

Bitcoin is one of the first implementations of a concept called "crypto-currency". Based on this concept, bitcoin is designed around the idea of a new form of money that uses cryptography to control its creation and transactions, rather than relying on central authorities.

Timeline

2008–2009

- In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper on The Cryptography Mailing list at metzdowd.com describing the bitcoin protocol.

- In 2009, the bitcoin network came into existence with the release of the first open source bitcoin client and the issuance of the first bitcoins.

2010

- The initial prices for bitcoins were set by individuals on the bitcointalk forums. The most significant transaction involved a 10,000 BTC pizza. The Mt.Gox bitcoin exchange was soon established.

- On 6 August, a major vulnerability in the bitcoin protocol was found. Transactions weren't properly verified before they were included in the transaction log or "blockchain" which allowed for users to bypass bitcoin's economic restrictions and create an indefinite number of bitcoins.

- On 15 August, the major vulnerability was exploited. Over 184 billion bitcoins were generated in a transaction, and sent to two addresses on the network. Within hours, the transaction was spotted and erased from the transaction log after the bug was fixed and the network forked to an updated version of the bitcoin protocol. This was the only major security flaw found and exploited in bitcoin's history.

2011–2012

- In June 2011, Wikileaks and other organizations began to accept bitcoin as donations. The Electronic Frontier Foundation initially did but has since stopped, citing concerns about a lack of legal precedent about new currency systems, and that they "generally don't endorse any type of product or service."

- In late-2011, the bitcoin price crashed from $30 to below $2 in what many would consider a "bubble". Some claimed the crash was due to a lower cost in producing bitcoins through cheaper computing power.

- In October 2012, BitPay reported having over 1000 merchants accepting Bitcoin under its payment processing service.

2013

February

- The bitcoin-based payment processor Coinbase reported selling $1 million in bitcoins in a single month, with a bitcoin being worth over $22.

- The Internet Archive announced that it is ready to accept donations in the form of bitcoin and that it intends to give employees the option to receive portions of their salaries in bitcoin currency.

March

- The bitcoin transaction log or "blockchain" temporarily forked into two independent logs with differing rules on how transactions could be accepted. The Mt.Gox bitcoin exchange briefly halted bitcoin deposits. Bitcoin prices briefly dipped by 23% to $37 as the event occurred before recovering to their previous level in the following hours, a price of approximately $48.

- In the US, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) established regulatory guidelines for "virtual currencies" such as bitcoin, classifying American "bitcoin miners" who sell their generated bitcoins as Money Service Businesses (or MSBs), that may now stand under registration and other legal obligations.

April

- Payment processor BitInstant and Mt.Gox experienced severe processing delays due to high demand for bitcoins, as its price increased.

- On the 10th, bitcoin crashed from a price of $266 to $105 before returning to a value of $160 within six hours.

Satoshi Nakamoto

Satoshi Nakamoto was the pseudonymous person or group of people who designed the original bitcoin protocol in 2008 and launched the bitcoin network in 2009. Beyond bitcoin, no other links to this identity have been found. His involvement in the original bitcoin protocol does not appear to extend past mid-2010. Nakamoto was active in making modifications to the bitcoin network and posting technical information on the BitcoinTalk Forum until his contact with bitcoin users began to fade. Until a few months before he left, he was responsible for creating the majority of the bitcoin protocol, only rarely accepting contributions.

In April 2011, Satoshi communicated to a bitcoin contributor saying he had “moved on to other things.”

Identity

Investigations into the real identity of Satoshi Nakamoto have been attempted by The New Yorker and Fast Company. Fast Company's investigation brought up circumstantial evidence that indicated a link between an encryption patent application filed by Neal King, Vladimir Oksman and Charles Bry on 15 August 2008, and the bitcoin.org domain name which was registered 72 hours later. The patent application (#20100042841) contained networking and encryption technologies similar to bitcoin's. After textual analysis, the phrase "...computationally impractical to reverse" was found in both the patent application and bitcoin's whitepaper. All three inventors explicitly denied being Satoshi Nakamoto.

The fork of March 2013

On 12 March 2013, a bitcoin server (also called a "miner") running the more recent "version 0.8.0" of the bitcoin protocol created a large record in bitcoin's transaction log (called the blockchain) that was incompatible with earlier versions of the bitcoin protocol due to its size. This created a split or "fork" in the transaction log. Some users ran the more recent version of the protocol, accepting and building on the diverging log, whereas other users ran older versions of the bitcoin protocol and rejected it. This split resulted in two separate transaction logs being formed without clear consensus, which allows for the same funds on both chains to be double-spent. In response, the Mt.Gox bitcoin exchange temporarily halted bitcoin deposits. The price of a bitcoin fell 23% to $37 on the Mt.Gox bitcoin exchange as this event occurred but subsequently rose most of the way back to its prior level of approximately $48.

Developers at bitcoin.org attempted to resolve the split by recommending that users downgrade to "version 0.7", which utilized the oldest transaction log in the split. User funds largely remained unaffected and were available when network consensus was reached. The network reached consensus and continued to operate as normal a few hours after the split.

FinCEN regulation

On 18 March 2013, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (or FinCEN), a bureau of the United States Department of the Treasury, issued a report regarding centralized and decentralized "virtual currencies" and their legal status within "money services business" (MSB) and Bank Secrecy Act regulations. It classified digital currencies and other digital payment systems such as bitcoin as "virtual currencies" because they are not legal tender under any sovereign jurisdiction. FinCEN cleared American users of bitcoin of legal obligations by saying, "A user of virtual currency is not an MSB under FinCEN’s regulations and therefore is not subject to MSB registration, reporting, and recordkeeping regulations." However, it held that American entities who generate "virtual currency" such as bitcoins are money transmitters or MSBs if they sell their generated currency for national currency: "...a person that creates units of convertible virtual currency and sells those units to another person for real currency or its equivalent is engaged in transmission to another location and is a money transmitter." This specifically extends to "miners" of the bitcoin network who may have to register as an MSB and abide by the respective requirements of being a money transmitter if they sell their generated bitcoins for national currency and are within the United States.

Additionally, FinCEN claimed regulation over American entities that manage bitcoins in a payment processor setting or as an exchanger: "In addition, a person is an exchanger and a money transmitter if the person accepts such de-centralized convertible virtual currency from one person and transmits it to another person as part of the acceptance and transfer of currency, funds, or other value that substitutes for currency."

In summary, FinCEN's decision would require Bitcoin exchanges where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies to disclose large transactions and suspicious activity, comply with money laundering regulations, and collect information about their customers as traditional financial institutions are required to do.

Patrick Murck of the Bitcoin Foundation criticized FinCEN's testament as an "overreach" and claimed that FinCEN "cannot rely on this guidance in any enforcement action".

2013 values

The USD value of a bitcoin increased ten-fold in early 2013 from $13/BTC on 1 January to $190/BTC on 9 April, three months later. Suggested reasons for the rise in price included the European sovereign-debt crisis – particularly the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis – statements by FinCEN improving the currency's legal standing and rising media and Internet interest.

As the market value of the total bitcoin supply approached $1 billion USD, financial commentators described bitcoin prices as a bubble. On 10 April 2013, Bitcoin dropped from a price of $266 to $105 before returning to a value of $160 within six hours.

Distribution

Unlike fiat currency, bitcoin has no centralized issuing authority. The network is programmed to increase the money supply as a geometric series until the total number of bitcoins reaches 21 million BTC, by issuing them to nodes that verify transaction records through intense bruteforce hashing with computing power. These nodes can then sell their earned bitcoins on exchanges or trade them at their discretion.

Currently, 25 bitcoins are generated every 10 minutes. This will be halved to 12.5 BTC within the year 2017 and halved continuously every 4 years after until a hard-limit of 21 million bitcoins is reached within the year 2140. As of March 2013 over 10.5 million of the total 21 million BTC had been created; the current total number created is available online. In November 2012, half of the total supply was generated, and by end of 2016, three-quarters will have been generated. By 2140, all bitcoins will have been generated with the last one consisting of fractional parts.

To ensure this granularity of the money supply, clients can divide each BTC unit down to eight decimal places (a total of 2.1 × 10 or 2.1 quadrillion units).

Exchange

Through various exchanges, bitcoins are bought and sold at a variable price against the value of other currency. Bitcoin has appreciated rapidly in relation to existing "fiat" currencies including the US dollar, euro and British pound.

In April 2013, 1 BTC traded from $100–$260. Taking into account the total number of bitcoins mined, the monetary base of the bitcoin network stands at over $1 billion USD.

According to Reuters, undisclosed documents indicate that banks such as Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have visited bitcoin exchanges as often as 30 times a day. Employees of international banks and major financial organizations have shown interest in the bitcoin markets as well.

Hedge funds

Financial laws can limit the type of assets institutional investors can buy, including alternative assets like bitcoin. However, assets stored in a licensed product can usually be bought by regulated entities. Exante Ltd., a Malta-based investment firm, launched a bitcoin hedge fund marketed towards institutional investors and high net-worth individuals. Bitcoin shares are currently traded through the Exante Hedge Fund Marketplace platform and authorized and regulated by the Malta Financial Services Authority. As of March 2013, Exante holds $3.2 million (2.5€ million) in bitcoin assets.

Derivatives

Derivatives on bitcoins are thinly available:

- iCBIT offers futures contracts on bitcoins against multiple currencies.

- In April 2013, IG Group began to offer binary options on the price of bitcoins at a given date.

Protocol

Summary

Bitcoin is a solution to the double-spending problem of using a peer-to-peer network to manage transactions. The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record or chain that cannot be changed without redoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain of records (called blocks) serves not only as proof of the sequence of events witnessed but also as proof that it came from the largest pool of computing power. As long as a majority of computing power is controlled by nodes that are not cooperating to attack the network, they'll generate the longest chain of records and outpace attackers.

The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages are broadcast on a best effort basis, and nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone.

Bitcoins

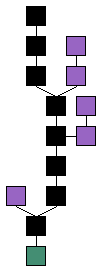

A bitcoin is defined by its chain of ECDSA digital signatures. Each owner transfers the coin to the next by digitally signing a hash of the previous transaction and the public key (or address) of the next owner and adding these to the end of the coin. A payee can verify the signatures to verify the chain of ownership.

Although it would be possible to handle coins individually, it would be unwieldy to make a separate transaction for every cent in a transfer. To allow value to be split and combined, transactions contain multiple inputs and outputs. Normally there will be either a single input from a larger previous transaction or multiple inputs combining smaller amounts, and at most two outputs: one for the payment, and one returning the change, if any, back to the sender.

It should be noted that fan-out, where a transaction depends on several transactions, and those transactions depend on many more, is not a problem here. There is never the need to extract a complete standalone copy of a transaction's history.

Hashes and signatures

Two SHA-256 hashes on top of each are used for transaction verification; however, RIPEMD-160 is used on top of a SHA256 hash for bitcoin digital signatures or "addresses". A bitcoin address is specifically the hash of a ECDSA public-key, computed this way:

Bitcoin address/Public-key = Version concatenated with RIPEMD-160(SHA-256(public key)) Checksum = 1st 4 bytes of SHA-256(SHA-256(Key hash)) Bitcoin Address = Base58Encode(Key hash concatenated with Checksum)

Timestamps

The bitcoin specification starts with a timestamp. A timestamp server works by taking a SHA256 hash function of a block of items to be timestamped and widely publishing the hash, such as in a newspaper or Usenet post. The timestamp proves that the data must have existed at the time, obviously, in order to get into the hash. Each timestamp includes the previous timestamp in its hash, forming a chain, with each additional timestamp reinforcing the ones before it.

Bitcoin mining

To implement a distributed timestamp server on a peer-to-peer basis, bitcoin uses a proof-of-work system similar to Adam Back's Hashcash, rather than newspaper or Usenet posts. This is often called bitcoin mining.

The mining process or proof-of-work process involves scanning for a value that when hashed with SHA-256, the hash begins with a number of zero bits. The average work required is exponential in the number of zero bits required, but can always be verified by executing a single hash.

For the bitcoin timestamp network, it implements the mining process or "proof-of-work" by incrementing a nonce in the record or "block" until a value is found that gives the block's hash the required zero bits. Once the hashing effort has been expended to make it satisfy the proof-of-work, the block cannot be changed without redoing the work. As later records or "blocks" are chained after it, the work to change the block would include redoing all the blocks after it.

The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, which has the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. If a majority of computing power is controlled by honest nodes, the honest chain will grow the fastest and outpace any competing chains. To modify a past block, an attacker would have to redo the proof-of-work of the block and all blocks after it and then catch up with and surpass the work of the honest nodes. The probability of a slower attacker catching up diminishes exponentially as subsequent blocks are added.

To compensate for increasing hardware speed and varying interest in running nodes over time, the proof-of-work difficulty is determined by a moving average targeting an average number of blocks per hour. If they're generated too fast, the difficulty increases.

Today, bitcoin mining is a competitive field. An arms race has been observed through the various hashing technologies that are used to mine bitcoins and confirm transactions: High-end GPUs (Graphical Processing Units) common in many gaming computers, FPGAs (Field Programmable Gate Arrays) and ASICs (Application-specific integrated circuits) all have been used. The newest addition, ASICS, are built into specialized servers that can cost nearly $3000 USD a unit.

Computing power is often bundled together from various servers or "pooled" into a central server to more effectively confirm blocks of transactions. Single servers often have to wait relatively long periods of time to confirm a block of transactions and receive payment for their "work" or hashing. When resources are "pooled", all participating servers receive a proportional number of the bitcoins earned every time any one participating server resolves a block.

Process

The steps to run the network and generate or "mine" bitcoins are:

- New transactions are broadcast to all nodes.

- Each node collects new transactions into a block.

- Each node works on finding a difficult proof-of-work for its block.

- When a node finds a proof-of-work, it broadcasts the block to all nodes.

- Bitcoins are successfully collected or "mined" by the receiving node which found the proof-of-work.

- Nodes accept the block only if all transactions in it are valid and not already spent.

- Nodes express their acceptance of the block by working on creating the next block in the chain, using the hash of the accepted block as the previous hash.

- Repeat.

Nodes always consider the longest chain to be the correct one and will keep working on extending it. If two nodes broadcast different versions of the next block simultaneously, some nodes may receive one or the other first. In that case, they work on the first one they received, but save the other branch in case it becomes longer. The tie will be broken when the next proof-of-work is found and one branch becomes longer; the nodes that were working on the other branch will then switch to the longer one.

New transaction broadcasts do not necessarily need to reach all nodes. As long as they reach many nodes, they will get into a block before long. Block broadcasts are also tolerant of dropped messages. If a node does not receive a block, it will request it when it receives the next block and realizes it missed one.

Mined bitcoins

By convention, the first transaction in a block is a special transaction that starts a new coin owned by the creator of the block. This adds an incentive for nodes to support the network, and provides a way to initially distribute coins into circulation, since there is no central authority to issue them.

The continual and steady addition of new coins is analogous to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation. In this case, it is computing power and electricity that is expended.

The incentive can also be funded with transaction fees. If the output value of a transaction is less than its input value, the difference is a transaction fee that is added to the incentive value of the block containing the transaction.

Local system resources

Once the latest transaction of a coin is buried under enough blocks, the spent transactions which preceded it can be discarded in order to save disk space. To facilitate this without breaking the block's hash, transactions are hashed in a Merkle tree, with only the root included in the block's hash. Old blocks can then be compacted by stubbing off branches of the tree. The interior hashes need not be stored.

A block header with no transactions would be about 80 bytes. Supposing that blocks are generated every 10 minutes, 80 bytes × 6 × 24 × 365 = 4.2 MB per year. With computer systems typically selling with 2 GB of RAM as of 2008, and Moore's law predicting current growth of 1.2 GB per year, storage should not be a problem even if the block headers need to be kept in memory.

Payment verification

It is possible to verify bitcoin payments without running a full network node. A user only needs to keep a copy of the block headers of the longest proof-of-work chain, which he can get by querying network nodes until he is convinced he has the longest chain, and obtain the Merkle branch linking the transaction to the block it is timestamped in. He can not check the transaction for himself, but by linking it to a place in the chain, he can see that a network node has accepted it, and blocks added after it further confirm the network has accepted it.

As such, the verification is reliable as long as honest nodes control the network, but is more vulnerable if the network is overpowered by an attacker. While network nodes can verify transactions for themselves, the simplified method can be fooled by an attacker's fabricated transactions for as long as the attacker can continue to overpower the network. To protect against this, alerts from network nodes detecting an invalid block prompt the user's software to download the full block and verify alerted transactions to confirm their inconsistency. Businesses that receive frequent payments will probably still want to run their own nodes for more independent security and quicker verification.

Applications

The bitcoin protocol introduces various technologies and economic properties that have numerous applications.

Financial haven

Financial journalists and analysts have speculated that there was a correlation between higher bitcoin usage in Spain and the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis, through which bank deposit levies as high as 40% could have been placed on bank deposits; conceding that bitcoin is serving as a sort of financial haven for some European savers. Nick Colas, a financial analyst, claimed a rally in the price of bitcoins was “One hundred percent...due to Cyprus,” and that “It means the Europeans are getting involved.”

In contrast, as of 2013, the use of bitcoin as a haven is limited for large amounts. As Colas also claims, “Bitcoin is good if you want to make a deposit of between $1,000 and $10,000. But the liquidity is just not there in the system for multimillion dollar transactions...”

Namecoin DNS

Namecoin is an alternative peer-to-peer Domain Name System that is based on the open-source bitcoin protocol. Like bitcoin, the Namecoin network reaches consensus every few minutes as to which names/values have been reserved or updated. Each user has its own copy of the full database, which attempts to reduce censorship on the DNS level. The use of public-key cryptography also means that only the owner is allowed to modify a name in the distributed database. For name resolution Namecoin uses .bit as pseudo-top-level domain.

Implications

As a currency

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (March 2013) |

The large fluctuations in the dollar value of bitcoin has evoked criticism of bitcoin's economic suitability and legitimacy as a currency. An April 2013 article in The Atlantic stated that although bitcoin is purported to be a currency, it cannot be a currency due to its deflationary bias, which encourages hoarding. Forbes contributor Louis Woodhill stated that bitcoins are the cyber equivalent of rare postage stamps, or collectibles and can never be money. It has been noted that as a currency not under sovereign control, bitcoin is currently being used on the black-market Silk Road website and is used by Iranians to evade foreign currency sanctions. Conversely, there is also some evidence that it is being accepted by some mainstream businesses and hoarded by some individuals. There has also been growing awareness of its usage in black market transactions, frustrating its promoters. In 2013, the U.S. Treasury extended its anti-money laundering regulations to processors of bitcoin transactions.

As an investment

Although it is considered by supporters to be a digital currency, virtual currency, or "payment scheme", it is often traded as an investment and accused of being a form of investment fraud known as a Ponzi scheme. On this subject, a report by the European Central Bank, using the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's definition of a Ponzi scheme, found that the use of bitcoins shares some characteristics with Ponzi schemes, but also has characteristics of its own which contradict several common aspects of Ponzi schemes.

In contrast, The Bitcoin Project describes bitcoin exclusively as an "experimental digital currency" and does not refer to it as an investment. Like many things considered to be investments, Bitcoins are also subject to theft.

Value

Bitcoins, as an investment, have been described as lacking intrinsic value because their value depends only on the willingness of users to accept it. As such, bitcoins have been compared to a type of fiat currency that is not issued by a central government.

Privacy

Bitcoin transactions are seen as relatively anonymous. Bitcoin is the medium of exchange on the Silk Road, an online black market. Some proponents of Bitcoin are concerned that such an association may bring about a negative perception of the currency.

The privacy of Bitcoin is a field of active academic research. Because Bitcoin transactions are broadcast to the entire network, they are inherently public. Using external information, it is possible, though usually difficult, to associate Bitcoin identities with real-life identities. Unlike regular banking, which preserves customer privacy by keeping transaction records private, loose transactional privacy is accomplished in Bitcoin by using many unique addresses for every wallet, while at the same time publishing all transactions. An IEEE paper proposing a cryptographic extension to Bitcoin —Zerocoin— has been published.

Botnet mining

In June 2011, Symantec warned about the possibility of botnets engaging in covert "mining" of bitcoins, consuming computing cycles, using extra electricity and possibly increasing the temperature of the computer. Some malware also used the parallel processing capabilities of the GPUs built into many modern-day video cards.

Later that month, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation caught an employee using the company's servers to generate Bitcoins without permission.

In mid-August 2011, Bitcoin miner botnets were found again, less than three months later bitcoin-mining trojans infecting Mac OS X were also discovered.

Incidents of theft

There have been incidents of theft of bitcoin balances:

- On 19 June 2011, a security breach of the Mt.Gox (Magic: The Gathering Online Exchange) bitcoin exchange caused the nominal price of a bitcoin fraudulently to drop to one cent on the Mt.Gox exchange, after a hacker allegedly used credentials from a Mt.Gox auditor's compromised computer illegally to transfer a large number of bitcoins to himself. He used the exchange's software to sell them all nominally, creating a massive "ask" order at any price. Within minutes the price corrected to its correct user-traded value. Accounts with the equivalent of more than USD 8,750,000 were affected.

- In July 2011, the operator of Bitomat, the third largest bitcoin exchange, announced that he lost access to his wallet.dat file with about 17,000 bitcoins (roughly equivalent to 220,000 USD at that time). He announced that he would sell the service for the missing amount, aiming to use funds from the sale to refund his customers.

- In August 2011, MyBitcoin, a now defunct bitcoin transaction processor, declared that it was hacked, which resulted in it being shut down, with paying 49% on customer deposits, leaving more than 78,000 bitcoins (roughly equivalent to 800,000 USD at that time) unaccounted for.

- In early August 2012, a lawsuit was filed in San Francisco court against Bitcoinica — a bitcoin trading venue — claiming about 460,000 USD from the company. Bitcoinica was hacked twice in 2012, which led to allegations of neglecting the safety of customers' money and cheating them out of withdrawal requests.

- In late August 2012, an operation titled Bitcoin Savings and Trust was shut down by the owner, allegedly leaving around $5.6 million in bitcoin-based debts; this led to allegations of the operation being a Ponzi scheme. In September 2012, it was reported that U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has started an investigation on the case.

- In September 2012, Bitfloor, a bitcoin exchange, also reported being hacked, with 24,000 bitcoins (roughly equivalent to 250,000 USD) stolen. As a result, Bitfloor suspended operations. The same month, Bitfloor resumed operations, with its founder saying that he reported the theft to FBI, and that he is planning to repay the victims, though the time frame for such repayment is unclear.

- On 3 April 2013, Instawallet, a web-based wallet provider, was hacked, resulting in the theft of over 35,000 bitcoins ($129.90 at the time of trade, or nearly $4.6 million USD.) Instawallet suspended operations.

Taxation

Matthew Elias, founder of the Cryptocurrency Legal Advocacy Group (CLAG) published "Staying Between the Lines: A Survey of U.S. Income Taxation and its Ramifications on Cryptocurrencies", which discusses "the taxability of cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin." CLAG "stressed the importance for taxpayers to determine on their own whether taxes are due on a bitcoin-related transaction based on whether one has "experienced a realization event." Such examples are "when a taxpayer has provided a service in exchange for bitcoins, a realization event has probably occurred, and any gain or loss would likely be calculated using fair market values for the service provided."

Reception

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (April 2013) |

In 2011, Paul Krugman, a Keynesian economist, reviewed bitcoin saying that " has fluctuated sharply, but overall it has soared. So buying into has, at least so far, been a good investment. But does that make the experiment a success? Um, no. What we want from a monetary system isn’t to make people holding money rich; we want it to facilitate transactions and make the economy as a whole rich. And that’s not at all what is happening in ."

In March 2013, Nick Colas a Chief Market Strategist at ConvergEx Group, a Bank of New York Mellon investment firm – analyzed bitcoin, saying "there is much to learn from in the world of stateless currencies," and that "confidence in money as a store of value is the ultimate driver of its value, both in the cyber and real worlds. I have no idea which way will trade in the next 2 days or 2 years, but the whole process of starting a new Internet currency is a great case study in how real people use real currency."

In April 2013, an analysis by financial journalist Felix Salmon—formerly of Portfolio Magazine, Euromoney and a blogging editor for Reuters—considered the current of price of bitcoins to be a bubble. He noted that while the value of bitcoins is strongly affected by news media exposure and that they are an "uncomfortable combination of commodity and currency," Bitcoin was "in many ways the best and cleanest payments mechanism the world has ever seen."

Economist John Quiggin has claimed that "Bitcoin is perhaps the finest example of a pure bubble", and that it provides a conclusive refutation of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH). While other assets used as currency—such as gold, tobacco and U.S. dollars—have value independent of people's willingness to accept them as payment, Quiggin argues that "in the case of Bitcoin there is no source of value whatsoever" and that:

Since Bitcoins do not generate any actual earnings, they must appreciate in value to ensure that people are willing to hold them. But an endless appreciation, with no flow of earnings or liquidation value, is precisely the kind of bubble the EMH says can’t happen.

Heidi Moore, US finance and economics editor at The Guardian stated that Bitcoin is not a legitimate currency. She writes:

An obscure digital currency, used mostly for running drugs and laundering money for dictators... Bitcoin is a currency created years ago by an obscure hacker in the spirit of subversion, to trade goods while dodging the gimlet eye of financial regulators. While theoretically it can be used for respectable online purchases, it is too complicated to buy and maintain for people who aren't online 18 hours a day, so it is used primarily to fuel a shadow economy of vice.

Popular culture

The Good Wife

Bitcoin was featured as a subject within a fictionalized trial on the CBS legal drama The Good Wife in the third season episode "Bitcoin for Dummies". The host of CNBC's Mad Money, Jim Cramer, played himself in a courtroom scene where he testifies that he doesn’t consider bitcoin a true currency, saying “There’s no central bank to regulate it; it’s digital and functions completely peer to peer.”

See also

- Anonymous Internet banking

- Complementary currency

- Crypto-anarchism

- Digital currency exchanger

- Internet privacy

- Private currency

- Ripple monetary system

- Ven (currency)

External links

- Satoshi Nakamoto's original paper, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System

- A cogent critique of Bitcoin, with suggestions for an improved cryptocurrency

- An illustrated history of Bitcoin crashes from Forbes

- An appreciation from The Economist of Bitcoin as a new specie

- A paper from Stanford University

- Bitcoin Wiki

References

- Matonis, Jon (22 January 2013). "Bitcoin Casinos Release 2012 Earnings". Forbes. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

Responsible for more than 50% of daily network volume on the Bitcoin blockchain, SatoshiDice reported first year earnings from wagering at an impressive ฿33,310.

- ^ "Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency". Daily Tech. 12 June 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi (24 May 2009). "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (PDF). Retrieved 20 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Bitter to Better — how to make Bitcoin a better currency" (PDF). Financial Cryptography and Data Security. Springer. 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "UCPaper" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Ron Dorit. "Quantitative Analysis of the Full Bitcoin Transaction Graph" (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive. p. 17. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hough, Jack (3 June 2011). "The Currency That's Up 200,000%". SmartMoney. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ Wallace, Benjamin (23 November 2011). "The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin". Wired. Retrieved 13 October 2012. Cite error: The named reference "Wired:RFB" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- https://www.spendbitcoins.com/places/

- http://www.americanbanker.com/issues/177_209/bitcoin-merchants-plan-own-version-of-black-friday-1053951-1.html

- http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2013/04/11/bitcoin-electronic-cash-beloved-by-hackers/

- http://www.forbes.com/sites/louiswoodhill/2013/04/11/bitcoins-are-digital-collectibles-not-real-money/ Forbes: Bitcoins are not real money

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/04/11/yes-bitcoin-is-volatile-its-still-got-defenders/

- Zeitlin, Matthew. "Bitcoin's Wild Ride Shows It's Not Real Money". Bloomberg. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Krugman, Paul. "Golden Cyberfetters". New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Network Deficit". blockchain.info. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "The British Museum – Token". Trustees of the British Museum. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper". 31 October 2008.

- "Satoshi's posts to Cryptography mailing list". Mail-archive.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Block 0 – Bitcoin Block Explorer".

- "Bitcoin v0.1 released".

- "SourceForge.net: Bitcoin".

- ^ Sawyer, Matt. "The Beginners Guide To Bitcoin – Everything You Need To Know". Monetarism. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Vulnerability Summary for CVE-2010-5139". National Vulnerability Database. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- Greenberg, Andy (2011-06-14). 14/wikileaks-asks-for-anonymous-bitcoin-donations/ "WikiLeaks Asks For Anonymous Bitcoin Donations – Andy Greenberg – The Firewall – Forbes". logs.forbes.com. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - "EFF and Bitcoin | Electronic Frontier Foundation". Eff.org. 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Arthur, Charles. "Bitcoin value crashes below cost of production as broader use stutters". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "BitPay Signs 1,000 Merchants to Accept Bitcoin Payments". American Banker. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- Ludwig, Sean. "Y Combinator-backed Coinbase now selling over $1M Bitcoin per month". VentureBeat. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Mandalia, Ravi (22 February 2013). "The Internet Archive Starts Accepting Bitcoin Donations". Parity News. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ Lee, Timothy. "Major glitch in Bitcoin network sparks sell-off; price temporarily falls 23%". Arstechnica. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Blagdon, Jeff. "Technical problems cause Bitcoin to plummet from record high, Mt. Gox suspends deposits". The Verge. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Bitcoin Charts".

- ^ Lee, Timothy. "http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2013/03/us-regulator-bitcoin-exchanges-must-comply-with-money-laundering-laws/". Arstechnica. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

Bitcoin miners must also register if they trade in their earnings for dollars.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "US govt clarifies virtual currency regulatory position". Finextra. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Application of FinCEN's Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies" (PDF). Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/04/inside-the-bitcoin-bubble-bitinstants-ceo.html

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus. "Bitcoin crashes, losing nearly half of its value in six hours". Arstechnica. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). "The Crypto-Currency". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Penenberg, Adam. "The Bitcoin Crypto-Currency Mystery Reopened". FastCompany. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Greenfield, Rebecca (11 October 2011). "The Race to Unmask Bitcoin's Inventor(s)". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Karpeles, Mark. "Bitcoin blockchain issue – bitcoin deposits temporarily suspended". Mt.Gox. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "11/12 March 2013 Chain Fork Information". Bitcoin Project. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Bitcoin software bug has been rapidly resolved". ecurrency. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Lee, Timothy. "New Money Laundering Guidelines Are A Positive Sign For Bitcoin". Forbes. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- "The rise of the bitcoin: Virtual gold or cyber-bubble?". Washington Post. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Murck, Patrick. "Today, we are all money transmitters... (no, really!)". Bitcoin Foundation. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- Traverse, Nick. "Bitcoin's Meteoric Rise". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Bustillos, Maria. "The Bitcoin Boom". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Seward, Zachary. "Bitcoin, up 152% this month, soaring 57% this week". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- "A Bit expensive". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Estes, Adam. "Bitcoin Is Now A Billion Dollar Industry". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Salmon, Felix. "The Bitcoin Bubble and the Future of Currency". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Ro, Sam. "Art Cashin: The Bitcoin Bubble". Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Lowenthal, Thomas (8 June 2011). "Bitcoin: inside the encrypted, peer-to-peer digital currency". Ars Technica.

- "Virtual currency: Bits and bob". The Economist. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Geere, Duncan. "Peer-to-peer currency Bitcoin sidesteps financial institutions (Wired UK)". Wired.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- "Total Number of Bitcoins in Existence". Bitcoin Block Explorer. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- Nathan Willis (2010-11-10). "Bitcoin: Virtual money created by CPU cycles". LWN.net.

- "Market Capitalization". Blockchain.info. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Mt.Gox data". Bitcoincharts.

- ^ O'Leary, Naomi. "Bitcoin, the City traders' anarchic new toy". Reuters. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

Workers at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs in London and New York have been visiting online Bitcoin exchanges as often as 30 times a day, according to documents seen by Reuters. Neither bank wanted to comment. Employees at almost all the major international banks and numerous trading and investment firms have shown interest.

Cite error: The named reference "Reuters1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Matonis, Jon. "First Bitcoin Hedge Fund Launches From Malta". Forbes. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Foxman, Simone. "How to short bitcoins (if you really must)". Quartz. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- "IG Market Index (Search "Bitcoin")". IG Markets. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Tindell, Ken. "Geeks Love The Bitcoin Phenomenon Like They Loved The Internet In 1995". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Biggs, John. "How To Mine Bitcoins". Techcrunch. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Cox, Jeff (Mar 27). "Bitcoin Bonanza: Cyprus Crisis Boosts Digital Dollars". CNBC. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - Steadman, Ian. "Technology Bitcoin interest spikes in Spain as Cyprus financial crisis grows". Wired. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Salyer, Kirsten. "Fleeing the Euro for Bitcoins". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Warner, Bernhard. "Jittery Spaniards Seek Safety in Bitcoins". Business Week. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Gallagher, Sean (2011-11-18). "Anonymous "dimnet" tries to create hedge against DNS censorship". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Moore, Heidi. "Confused about Bitcoin? It's 'the Harlem Shake of currency'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- O;Brien, Matthew. "Bitcoin Is No Longer a Currency". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - http://www.forbes.com/sites/louiswoodhill/2013/04/11/bitcoins-are-digital-collectibles-not-real-money/ Forbes: botcoins are digital collectibles not real money.

- Raskin, Max (November 29). "Dollar-Less Iranians Discover Virtual Currency". BloombergBusinessWeek. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2013/mar/04/bitcoin-currency-of-vice

- http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/11/as-big-investors-emerge-bitcoin-gets-ready-for-its-close-up/

- http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2013/04/11/bitcoin-electronic-cash-beloved-by-hackers/

- http://blog.aarp.org/2013/04/11/bitcoin-currency-hackers-make-money-investing-in-bitcoins-scams/

- Gustke, Constance (23 November 2011). "The Pros And Cons Of Biting on Bitcoins". CNBC. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Chirgwin, Richard (8 June 2011). "US senators draw a bead on Bitcoin". The Register. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- "Virtual Currency Schemes" (PDF). European Central Bank. October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "Bitcoin – P2P digital currency". Bitcoin Project. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

© Bitcoin Project 2009–2012

- ^ Hough, Jack. "The Bitcoin Triples Again". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

To recap, it's is a purely online currency with no intrinsic value; its worth is based solely on the willingness of holders and merchants to accept it in trade.

- ^ Justin Fox. Building a Better Bitcoin. Harvard Business Review. 2013-04-09. Accessed 2013-04-09.

- http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2013/04/11/what-the-bitcoin-crash-can-teach-us-about-money-an.aspx

- The Economist. Monetarists Anonymous. 2012-09-29. Accessed 2013-04-01.

- Andy Greenberg (20 April 2011). Crypto Currency. Forbes Magazine.

- Madrigal, Alexis (2011-06-01). "Libertarian Dream? A Site Where You Buy Drugs With Digital Dollars". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- Jeff Garzik. The Underground Website Where You Can Buy Any Drug Imaginable. Gawker.

- http://eprint.iacr.org/2012/596.pdf

- Fergal Reid and Martin Harrigan (24 July 2011). An Analysis of Anonymity in the Bitcoin System. An Analysis of Anonymity in the Bitcoin System.

- The Economist. Monetarists Anonymous. 2012-09-29. Accessed 2013-04-01.

- "Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists' Answer to Cash". IEEE.org. June 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- http://spar.isi.jhu.edu/~mgreen/ZerocoinOakland.pdf

- http://blog.cryptographyengineering.com/2013/04/zerocoin-making-bitcoin-anonymous.html

- Peter Coogan (2011-06-17). "Bitcoin Botnet Mining". Symantec.com. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "Researchers find malware rigged with Bitcoin miner". ZDNet. 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- Goodin, Dan (16 August 2011). "Malware mints virtual currency using victim's GPU".

- "ABC employee caught mining for Bitcoins on company servers". The Next Web. 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "Infosecurity – Researcher discovers distributed bitcoin cracking trojan malware". Infosecurity-magazine.com. 2011-08-19. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- "Mac OS X Trojan steals processing power to produce Bitcoins – sophos, security, malware, Intego – Vulnerabilities – Security". Techworld. 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2012-01-24.

- Karpeles, Mark (2011-06-30). "Clarification of Mt Gox Compromised Accounts and Major Bitcoin Sell-Off". Tibanne Co. Ltd.

- . YouTube BitcoinChannel. June 19, 2011. Event occurs at Bitcoin Report Volume 8 – (FLASHCRASH) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T1X6qQt9ONg.

{{cite AV media}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mick, Jason (19 June 2011). "Inside the Mega-Hack of Bitcoin: the Full Story". DailyTech.

- Timothy B. Lee, 19 June 2011, Bitcoin prices plummet on hacked exchange, Ars Technica

- Mark Karpeles, 20 June 2011, Huge Bitcoin sell off due to a compromised account – rollback, Mt.Gox Support

- Chirgwin, Richard (2011-06-19). "Bitcoin collapses on malicious trade – Mt Gox scrambling to raise the Titanic". The Register.

- Third Largest Bitcoin Exchange Bitomat Lost Their Wallet, Over 17,000 Bitcoins Missing. SiliconAngle

- MyBitcoin Spokesman Finally Comes Forward: “What Did You Think We Did After the Hack? We Got Shitfaced”. BetaBeat

- Search for Owners of MyBitcoin Loses Steam. BetaBeat

- Bitcoinica users sue for $460k in lost bitcoins. Arstechnica

- First Bitcoin Lawsuit Filed In San Francisco. IEEE Spectrum

- "Bitcoin ponzi scheme – investors lose $5 million USD in online hedge fund". RT.

- Jeffries, Adrianne. "Suspected multi-million dollar Bitcoin pyramid scheme shuts down, investors revolt". The Verge.

- Mick, Jason (August 28, 2012). ""Pirateat40" Makes Off $5.6M USD in BitCoins From Pyramid Scheme". DailyTech.

- Mott, Nathaniel (August 31, 2012). "Bitcoin: How a Virtual Currency Became Real with a $5.6M Fraud". PandoDaily.

- Bitcoin 'Pirate' scandal: SEC steps in amid allegations that the whole thing was a Ponzi scheme . The Telegraph

- "Bitcoin theft causes Bitfloor exchange to go offline". BBC News. 2012-09-25.

- Goddard, Louis (5 September 2012). "Bitcoin exchange BitFloor suspends operations after $250,000 theft". The Verge.

- Chirgwin, Richard (2012-09-25). "Bitcoin exchange back online after hack". PC World.

- Cutler, Kim-Mai (3 April 2013). "Another Bitcoin Wallet Service, Instawallet, Suffers Attack, Shuts Down Until Further Notice". TechCrunch. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Transaction details for bitcoins stolen from Instawallet

- ^ Stewart, David D. and Soong Johnston, Stephanie D. (2012). "2012 TNT 209-4 NEWS ANALYSIS: VIRTUAL CURRENCY: A NEW WORRY FOR TAX ADMINISTRATORS?. (Release Date: OCTOBER 17, 2012) (Doc 2012-21516)". Tax Notes Today. 2012 TNT 209-4 (2012 TNT 209-4).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Boesler, Matthew. "ANALYST: The Rise Of Bitcoin Teaches A Tremendous Lesson About Global Economics". Business Insider. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- The Bitcoin Bubble and the Future of Currency, Felix Salmon, Financial blogger at Reuters 3 April 2013

- Quiggin, John. "The Bitcoin Bubble and a Bad Hypothesis". The National Interest. Retrieved April 16 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Moore, Heidi (3 April 2013). "Confused about Bitcoin? It's 'the Harlem Shake of currency'". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Toepfer, Susan. "'The Good Wife' Season 3, Episode 13, 'Bitcoin for Dummies': TV Recap". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 January 2013.