| Revision as of 02:31, 25 July 2010 editTeeninvestor (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers8,552 edits Undo Athenean's intrusive move to remove valuable information of a renowned scholar.← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:44, 25 July 2010 edit undoTeeninvestor (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers8,552 edits I will back down for now and remove the quote since I don't have Temple's work on hand; however, once I have the book, I will provide a full quote, with the complete paragraph; hope this will help.Next edit → | ||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

| ==Equipment and technology== | ==Equipment and technology== | ||

| In their various campaigns, the Chinese armies employed a variety of equipment in the different arms of the army. Most of this equipment was very advanced for its day and helped the Chinese win victories over their opponents |

In their various campaigns, the Chinese armies employed a variety of equipment in the different arms of the army. Most of this equipment was very advanced for its day and helped the Chinese win victories over their opponents. | ||

| ===Infantry=== | ===Infantry=== | ||

Revision as of 02:44, 25 July 2010

| Chinese Armies (Pre-1911) | |

|---|---|

| Leaders | Chinese Emperor |

| Dates of operation | 2200 BCE - 1911 CE |

| Active regions | China, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Mongolia |

| Part of | Chinese Empire |

| Opponents | Donghu, Xirong, Vietnam, Xiongnu, Xianbei, Qiang, Jie, Di, Korea, Khitan, Gokturks, Tibetans, Jurchens, Mongols, Japan, and others. |

| Battles and wars | wars involving China |

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||

| History of China | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prehistoric

|

||||||||||||||||

Ancient

|

||||||||||||||||

Imperial

|

||||||||||||||||

Modern

|

||||||||||||||||

| Related articles | ||||||||||||||||

Ever since Chinese civilization was founded by the Xia Dynasty (2200 BCE-1600 BCE), organized military forces have existed throughout China. The recorded military history of China extends from about 2200 BCE to the present day. Although traditional Chinese Confucian philosophy favoured peaceful political solutions and showed contempt for brute military force, the military was influential in most Chinese states. The Chinese pioneered the use of crossbows, advanced metallurgical standardization for arms and armor, early gunpowder weapons, and other advanced weapons, but also adopted nomadic cavalry and Western military technology. In addition, China's armies also benefited from an advanced logistics system as well as a rich strategic tradition, beginning with Sun Tzu's "The Art of war", that deeply influenced military thought.

Early Chinese armies, such as that of the Xia, Shang and Zhou, were based on chariots and bronze weapons, much like their contemporaries in western Asia and Egypt. These small armies were ill-trained, poorly equipped, and had poor endurance However, by the Warring States Period, the introduction of iron weapons, crossbows, and cavalry revolutionized Chinese warfare. Professional standing armies replaced the unreliable peasant levies of old, and professional generals replaced aristocrats at the head of the army. This occurred concurrently with the establishment of a centralized state that was to become the norm for China. Under the Qin and Han Dynasties, China was unified and its troops conquered territories in all directions, and established China's frontiers that would last to the present day. These victories ushered in a golden age for China.

Despite occasional defeats, particularly by the nomads on the northern frontier, China maintained a strong and powerful army throughout most of the imperial Era. Although the army became gradually feudal after the fall of the Han Dynasty, a trend that was accelerated during the Wu Hu invasions of the fourth century CE and the Southern and Northern Dynasties period afterwards, a professional army was restored by the Sui Dynasty and Tang Dynasty, bringing a new golden age. Military technology also did not stand still; new equipment and concepts such as gunpowder weaponry and powerful new naval ships were continuously introduced, in order to augment the fighting power of China's military forces.

Despite this, China's military supremacy gradually eroded after the establishment of the Song Dynasty, who was distrustful of the military establishment. Under the Song, China's armies suffered disastrous reverses and China was conquered by the Mongols under Kublai Khan. Although the Ming Dynasty restored Chinese power and a new golden age, China's supremacy was ended by a second foreign conquest, that of the Manchu Qing Dynasty in 1683. They put a stop to improvements in military technology in order to maintain their rule. The Qing Dynasty suffered disastrous defeats to European powers throughout the 19th century that eroded China's sovereignty and lead to the disintegration of the Chinese Empire.

Early Chinese armies were composed of infantry and charioteers, with imperial Chinese armies numbering hundreds of thousands of men. These armies were composed of crossbowmen, cavalry, and infantry, who were armed with a wide array amount of equipment. After the Song Dynasty, Chinese armies were also equipped with gunpowder weapons such as muskets and cannons. These armies were usually composed mostly of ethnic Chinese, though the Chinese army also employed many subject peoples in their forces, such as Gokturks, Koreans, and Mongols. The Yuan and Qing dynasties, under whom China were ruled by ethnic minorities such as the Mongols and Manchus, employed large numbers of Inner Asian cavalry troops mostly from their own ethnic group, while the infantry are composed of mostly ethnic Han soldiers.

History

The military history of China stretches from roughly 2200 BCE to the present day. Chinese armies were advanced and powerful, especially after the Warring States Period. These armies were tasked with the twofold goal of defending China and her subject peoples from foreign intruders, and with expanding China's territory and influence across Asia

Pre-Warring States (2100 BCE-479 BCE)

Early Chinese armies were relatively small affairs. Composed of peasant levies, usually dependent serfs upon the king or the feudal lord, these armies were relatively ill equipped. While organized military forces had existed along with the state after the Xia Dynasty, little records remain of these early armies. These armies were centered around the chariot-riding nobility, who played a role akin to the European Knight as they were the main fighting force of the army. Bronze weapons such as spears and swords were the main equipment of the both the infantry and charioteers. These armies were ill-trained and haphazardly supplied, meaning that they could not campaign for more than a few months and often had to give up their gains due to lack of supplies.

Nevertheless, under the Xia, Shang, and Zhou, these armies were able to expand China's territory and influence from a narrow part of the Yellow river valley to all of the North China plain. Equipped with bronze weapons, bows, and armor, these armies won victories against the sedentary Donghu to the East and South, which were the main direction of expansion, as well as defending the western border against the nomadic incursions of the Xirong. However, after the collapse of the Zhou Dynasty in 771 BCE after the Xirong captured its capital Gaojing, China collapsed into a plethora of small states, who warred frequently with each other. The competition between these states would eventually produce the professional armies that marked the Imperial Era of China.

In 1978 a Chinese double edged steel sword dating back 2500 years was found in Changsha. The sword was mand during the Spring and Autumn period.

Warring states (479 BCE-221 BCE)

By the time of the Warring states, China had been consolidated into a series of large states. Centralized reforms began that abolished feudalism and created powerful, centralized states. In addition, the power of the aristocracy was curbed and for the first time, professional generals were appointed on merit, rather than birth. Technological advances such as iron weapons and crossbows put the chariot-riding nobility out of business and favored large, professional standing armies, who were well-supplied and could fight a sustained campaign. The size of armies increased; while before 500 BCE Chinese field armies did not exceed 100,000 men, the Battle of Changping in 260 BCE reputedly involved some 1,000,000 men from the two states involved. While this is certainly somewhat exaggerated, it served to show the increased size of armies in this era. The new military system was a centralized system that consisted of large armies commanded by professional generals, who had to report to a king.

In addition to these improvements, the Warring states also saw the introduction of a new arm of the army, cavalry. The first recorded use of cavalry took place in the Battle of Maling, in which general Pang Juan of Wei led his division of 5,000 cavalry into a trap by Qi forces. In 307 BC, King Wuling of Zhao ordered the adoption of nomadic clothing in order to train his own division of cavalry archers.

Qin-Han (221 BCE-184 CE)

In 221 BCE, the Qin unified China and ushered in the Imperial Era of Chinese history. Although it only lasted 15 years, Qin established institutions that would last for millennia. For the rest of Chinese history, a centralized empire was the norm.

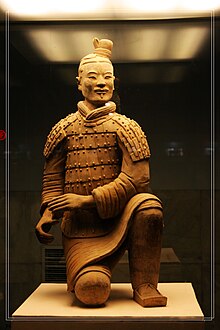

At the tomb of the first Qin Emperor and multiple Warring States period tombs, extremely sharp swords and other weapons were found which were coated with chromium oxide, which made the weapons rust resistant.. Chromium only came to the attention of westerners in the 18th century. The advanced alloys of tin and copper enabled weapons such as bronze knives and swords to remain sharp and unrusted despite fire and burial for 2000 years. A Qin crossbow was capable of shooting an arrow 800 metres.

During the Qin Dynasty and its successor, the Han, the Chinese armies were faced with a new military threat, that of nomadic confederations such as the Xiongnu in the North. These nomads were fast horse archers who had a significant mobility advantage over the settled nations to the South. In order to counter this threat, the Chinese built the Great Wall as a barrier to these nomadic incursions, and also used diplomacy and bribes to preserve peace. However, in the South, China's territory was roughly doubled as the Chinese conquered much of what is now Southern China, and extended the frontier from the Yangtze to Vietnam.

Armies during the Qin and Han dynasties largely inherited their institutions from the earlier Warring States Period, with the major exception that cavalry forces were becoming more and more important, due to the threat of the Xiongnu. Under Emperor Wu of Han, the Chinese launched a series of massive cavalry expeditions against the Xiongnu, defeating them and conquering much of what is now Northern China, Western China, Mongolia, Central Asia, and Korea. After these victories, Chinese armies were tasked with the goal of holding the new territories against incursions and revolts by peoples such as the Qiang, Xianbei and Xiongnu who had come under Chinese rule. Advances such as the stirrup helped make cavalry forces more effective. The Han also standardized and mass produced iron armor in the form of lamellar or coat of plates. The Eastern Han thoroughly developed heavily armored cavalry and lancers - while cavalry would eventually develop into the super-heavy cataphracts later on.

Wei-Jin (184 CE-304 CE)

The end of the Han Dynasty saw a massive agrarian uprising that had to be quelled by local governors, who seized the opportunity to form their own armies. The central army disintegrated and was replaced by a series of local warlords, who fought for power until most of the North was unified by Cao Cao, who later formed the Wei Dynasty, which ruled most of China. However, much of Southern China was ruled by two rival Kingdoms, Shu Han and Wu. As a result, this era is known as the Three Kingdoms.

Under the Wei Dynasty, the military system changed from the centralized military system of the Han. Unlike the Han, whose forces were concentrated into a central army of volunteer soldiers, Wei's forces depended on the Buqu, a group for whom soldiering was a hereditary profession. In effect, these armies were hereditary; when a soldier or commander died, a male relative would inherit the position. In addition, provincial armies, which were very weak under the Han, became the bulk of the army under the Wei, for whom the central army was held mainly as a reserve. This military system was also adopted by the Jin Dynasty, who succeeded the Wei and unified China

Era of division (304 CE-589 CE)

In 304 CE, a major event shook China. The Jin Dynasty, who had unified China 24 years earlier, was tottering in collapse due to a major civil war. Seizing this opportunity, barbarian chieftain Liu Yuan and his forces rose against the Chinese. He was followed by many other barbarian leaders, and these rebels were called the "Wu Hu" or literally "Five barbarian tribes". By 316 CE, the Jin had lost all territory north of the Huai river. From this point on, much of North China was ruled by Sinocized barbarian tribes such as the Xianbei, while south China remained under Chinese rule, a period known as the Era of Division. During this era, the military forces of both Northern and southern regimes diverged and developed very differently.

Northern

Northern China was devastated by the Wu Hu uprisings. After the initial uprising, the various tribes fought among themselves in a chaotic era known as the Sixteen Kingdoms. Although brief unifications of the North, such as Later Zhao and Former Qin, occurred, these were relatively short-lived. During this era, the Northern armies, were mainly based around nomadic cavalry, but also employed Chinese as foot soldiers and siege personnel. This military system was rather improvising and ineffective, and the states established by the Wu Hu were mostly destroyed by the Jin Dynasty or the Xianbei.

A new military system did not come until the invasions of the Xianbei in the 5th century CE, by which time most of the Wu Hu had been destroyed and much of North China had been reconquered by the Chinese dynasties in the South. Nevertheless, the Xianbei won many successes against the Chinese, conquering all of North China by 468 CE. The Xianbei state of Northern Wei created the earliest forms of the equal field (均田) land system and the Fubing system (府兵) military system, both of which became major institutions under Sui and Tang. Under the fubing system each headquarters (府) commanded about one thousand farmer-soldiers who could be mobilized for war. In peacetime they were self-sustaining on their land allotments, and were obliged to do tours of active duty in the capital.

Southern

Southern Chinese dynasties, being descended from the Han and Jin, prided themselves on being the successors of the Chinese civilization and disdained the Northern dynasties, who they viewed as barbarian usurpers. Southern armies continued the military system of Buqu or hereditary soldiers from the Jin Dynasty. However, the growing power of aristocratic landowners, who also provided many of the buqu, meant that the Southern dynasties were very unstable; after the fall of the Jin, four dynasties ruled in just two centuries.

This is not to say that the Southern armies did not work well. Southern armies won great victories in the late 4th century CE, such as the battle of Fei at which an 80,000-man Jin army crushed the 300,000-man army of Former Qin, an empire founded by one of the Wu Hu tribes that had briefly unified North China. In addition, under the brilliant general Liu Yu, Chinese armies briefly reconquered much of North China.

Sui-Tang (589 CE- 907 CE)

In 581 CE, the Chinese Yang Jian forced the Xianbei ruler to abdicate, founding the Sui Dynasty and restoring Chinese rule in the North. By 589 CE, he had unified much of China .

The Sui's unification of China sparked a new golden age. During the Sui and Tang, Chinese armies, based on the Fubing system invented during the era of division, won military successes that restored the empire of the Han Dynasty and reasserted Chinese power. The Tang created large contingents of powerful heavy infantry. A key component of the success of Sui and Tang armies, just like the earlier Qin and Han armies, was the adoption of large elements of cavalry. These powerful horsemen, combined with the superior firepower of the Chinese infantry (powerful missile weapons such as recurve crossbows), made Chinese armies powerful.

However, during the Tang Dynasty the Fubing (府兵)system began to break down. Based on state ownership of the land in the Juntian (均田)system, the prosperity of the Tang Dynasty meant that the state's lands were being bought up in ever increasing quantities. Consequently, the state could no longer provide land to the farmers, and the Juntian system broke down. By the 8th century, the Tang had reverted to the centralized military system of the Han. However, this also did not last and it broke down during the disorder of the Anshi Rebellion, which saw many Fanzhen (藩鎮)or local generals become extraordinarily powerful. These Fanzhen were so powerful they collected taxes, raised armies, and made their positions hereditary. Because of this, the central army of the Tang was greatly weakened. Eventually, the Tang Dynasty collapsed and the various Fanzhen were made into separate kingdoms, a situation that would last until the Song Dynasty.

During the Tang, professional military writing and schools began to be set up to train officers, an institution that would be expanded during the Song.

Song (960 CE-1279 CE)

During the Song Dynasty, the emperors were focused on curbing the power of the Fanzhen, local generals who they viewed as responsible for the collapse of the Tang Dynasty. Local power was curbed and most power was centralized in the government, along with the army. In addition, the Song adopted a system in which commands by generals were ad hoc and temporary; this was to prevent the troops from becoming attached to their generals, who could potentially rebel. Successful generals such as Yue Fei (岳飛)and Liu Zen were persecuted by the Song Court who feared they would rebel.

Although the system worked at quelling rebellions, it was a failure in defending China and asserting its power. The Song had to rely on new gunpowder weapons introduced during the late Tang and bribes to fend off attacks by its enemies, such as the Khitan, Tanguts, Jurchens, and Mongols. In addition, the Song was greatly disadvantaged by the fact their enemies had taken advantage of the era of chaos following the collapse of the Tang to conquer the Great Wall region, allowing them to advance into Northern China unimpeded. Not only that, but the Song also lost the horse-producing regions which made their cavalry extremely inferior. Eventually the Song fell to the Mongol invasions in the 13th century.

The military technology of the Song was very advanced. Gunpowder weapons, which during the Tang was only used to defend cities, acquiring a major role in the Song army as field weapons. This advanced technology was key for the Song army to fend off its barbarian opponents, such as the Khitans, Jur'chens and Mongols.

Yuan (1279 CE-1368 CE)

Founded by the Mongols who conquered Song China, the Yuan had the same military system as most nomadic peoples to China's north, focused mainly on nomadic cavalry, who were organized based on households and who were led by leaders appointed by the khan.

The Mongol invasion started in earnest only when they acquired their first navy, mainly from Chinese Song defectors. Liu Cheng, a Chinese Song commander who defected to the Mongols, suggested a switch in tactics, and assisted the Mongols in building their own fleet. Many chinese served in the Mongol navy and army and assisted them in their conquest of Song.

However, in the conquest of China, the Yuan also adopted gunpowder weapons and thousands of Chinese infantry and naval forces into the Mongol army, as well as non-Chinese weapons such as the Muslim counterweight trebuchets. . The Mongol military system began to collapse after the 14th century and by 1368 the Mongols was driven out by the Chinese Ming Dynasty.

Ming (1368 CE-1662 CE)

The Ming focused on building up a powerful standing army that could drive off attacks by foreign barbarians. Beginning in the 14th century, the Ming armies drove out the Mongols and expanded China's territories to include Yunnan, Mongolia, Tibet, much of Xinjiang and Vietnam. The Ming also engaged in Overseas expeditions which included one violent conflict in Sri Lanka. Ming armies incorporated gunpowder weapons into their military force, speeding up a development that had been prevalent since the Song. It is speculated that had the Manchu conquest of China not happened, the Ming army could have become completely equipped with gunpowder weapons, similar to 18th century Europe.

Throughout most of the Ming's history, the Ming armies were successful in defeating foreign powers such as the Mongols and Japanese and expanding China's influence. However, with the little Ice Age in the 17th century, the Ming Dynasty was faced with a disastrous famine and its military forces disintegrated as a result of the famines spurring from this event.

In 1662, a Ming-loyalist army led by Koxinga starved a Dutch East India Company fort on Taiwan in a seven month long siege into surrender. The final blow to the Company's defense came when a Dutch defector, who would save Koxinga's life in the assault, had pointed the inactive besieging army to the weak points of the Dutch star-shaped fort. While the mainstay of the Chinese forces were archers, the Chinese used cannons too during the siege,, which however the European eye-witnesses did not judge as effective as the Dutch batteries.

The Ming Dynasty Imperial Navy defeated a Portuguese navy led by Martim Affonso in 1522 at the Battle of Tamao. The Chinese destroyed one vessel by targeting its gunpowder magazine, and captured another Portuguese ship.

Qing (1662 CE-1911 CE)

The Qing were another conquest dynasty, similar to the Yuan. The Qing military system depended on the "bannermen" who were Manchus that soldiered as a profession. However, the Qing also incorporated Chinese units into their army, known as the "green armies", and large number of Han Chinese and Koreans of Liao Dong(遼東) were enslaved and enlisted into Three Banner Army (booi ilan gusa), which were under direct command of the Manchu Emperor. Unlike the Song and Ming, however, the Qing armies had a strange neglect for firearms, and did not develop them in any significant way. In addition, the Qing armies also contained a much higher proportion of cavalry than Chinese dynasties, due to the fact the Jurchens were nomads before their rise to rule all of China.

The Qing dynasty engaged a western power for the second time in Chinese history, during the Russian–Manchu border conflicts, again defeating them in battle.

The Qing won many military successes in the Northwest, and were successful in reincorporating much of Mongolia and Xinjiang into China after the fall of the Ming Dynasty, as well as strengthening control over Tibet. However, when faced with western armies in the 19th century, the Qing's military system began to collapse. The only one battle that Qing one with heavier casualties inflicted on the Western side during this era was the Battle of Taku Forts (1859), in which the Chinese used gunpowder weapons like Cannons and muskets to destroy three Anglo French ships and inflict heavy casualties. To compensate for this, a series of "new armies" based on European standards, were formed by the Qing. These armies were mainly composed of Han Chinese, and under Han Chinese commanders such as Zeng Guofan, Zuo Zongtang, Li Hongzhang and Yuan Shikai and thus weakened the Manchus' hold on military power. The Qing also absorbed bandit armies and Generals who defected to the Qing side during rebellions, like the Muslim Generals Ma Zhan'ao, Ma Qianling, Ma Haiyan, and Ma Julung. There were also armies composed of Chinese Muslims led by Muslim Generals like Dong Fuxiang, Ma Anliang, Ma fuxiang, and Ma Fuxing who commanded the Kansu Braves. In 1911 CE, the Chinese revolution overthrew the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and Yuan Shikai forced the Manchu monarch to resign peacefully on the promise that not a single Manchu royal be executed by revolutionaries, and thus began the modern era of Chinese history.

Military philosophy

Chinese military thought's most famous tome is Sun Tzu's Art of war, written in the Warring States Era. In the book, Sun Tzu laid out several important cornerstones of military thought, such as:

- The importance of intelligence.

- The importance of manoeuvring so your enemy is hit in his weakened spot.s

- The importance of morale.

- How to conduct diplomacy so that you gain more allies and the enemy lose allies.

- Having the moral advantage.

- The importance of national unity.

- All warfare is based on deception.

- Logistics.

- The proper relationship between the ruler and the general. Sun Tzu holds the ruler should not interfere in military affairs.

- Difference between Strategic and Tactical strategy.

- No country has benefited from a prolonged war.

- Subduing an enemy without using force is best.

Sun Tzu's work became the cornerstone of military thought, which grew rapidly. By the Han Dynasty, no less than 11 schools of military thought were recognized. During the Song Dynasty, a military academy was established.

Equipment and technology

In their various campaigns, the Chinese armies employed a variety of equipment in the different arms of the army. Most of this equipment was very advanced for its day and helped the Chinese win victories over their opponents.

Infantry

The Chinese infantry employed steel weapons, such as halberds and spears, in close-range fighting, though swords and blades were also used. In addition, the Chinese infantry were given extremely heavy armor in order to withstand cavalry charges, some 29.8 kg of armor during the Song Dynasty. Chinese soldiers also used the first steel weapons, which gave them high-grade weapons that were superior to any weapons their opponents could carry.

Cavalry

The cavalry was equipped with heavy armor in order to crush a line of infantry, though light cavalry was used for reconnaissance. However, Chinese armies lacked horses and their cavalry were often inferior to their horse archer opponents. Therefore, in most of these campaigns, the cavalry had to rely on the infantry to provide support.

Missile troops

Missile troops were another important part of the Chinese army. Crossbows were the first weapon used for this role, and crossbows were easily able to stop cavalry advances through their penetrating power and use en masse. After the Song Dynasty, gunpowder weapons were used in large quantities to fulfil this role. Though early gunpowder weapons were primitive, such as the fire-lance, by the Ming Dynasty true guns and cannons were used in large quantities. Chinese missile weapons included fire bombs, poison bombs and multi-stage rockets. Joseph Needham noted that:

a battalion in the fifteenth century Chinese army had up to 40 cannon batteries, 3600 thunder-bolt shells, 160 cannons, 200 large and 328 small "grapeshot" cannons, 624 handguns, 300 small grenades, some 6.97 tons of gunpowder and no less than 1,051, 600 bullets, each of 0.8 ounces. Needham remarked that this was "quite some firepower" and the total weight of the weapons were 29.4 tons.

Siege elements

Siege elements were also prevalent throughout the Chinese army in order to capture cities. Siege towers, catapults, and siege ladders were available since the warring states. Later on, cannons were used to break city walls.

Unconventional weapons

In addition to the above, the Chinese also employed a large number of unconventional weapons, including flamethrowers, landmines, repeating guns, and poison gas.

Logistics

The Chinese armies also benefited from a logistics system that could supply hundreds of thousands of men at a time.

Command

In early Chinese armies, command of the armies were based on birth rather than merit. For example, for the state of Qi in the Spring and Autumn Era (771 BCE-479 BCE), the command of the armies were delegated to the ruler, the crown prince, and the second son. By the warring states, however, generals were appointed based on merit rather than birth, and the majority of generals came from talented individuals who gradually rose through the ranks.

Nevertheless, Chinese armies were sometimes commanded by individuals other than generals. For example, during the Tang Dynasty, the emperor instituted "Army supervisors" who spied on the generals and interfere in command. Although most of these practices were short-lived, they were disruptive to the efficiency of the army.

Major battles and campaigns

- Battle of Muye

- Battle of Chengpu

- Battle of Jinyang

- Battle of Changping

- Battle of Gaixia

- Sino-Xiongnu War

- Battle of Mayi

- Battle of Mobei

- Battle of Chibi

- Wu Hu uprising

- Wei-Jie war

- Battle of Fei

- Liu Yu's expeditions

- Battle of Shayuan

- Battle of Salsu

- Tang-Gokturk wars

- Battle of Baekgang

- Battle of Talas

- Battle of Suiyang

- Battle of Tangdao

- Battle of Caishi

- Battle of Xiangyang

- Mongol conquest of the Song Dynasty

- Yongle's expeditions against Mongolia

- Imjin War

- Opium wars

- Sino-French war

- First Sino-Japanese war

See also

References

- Li and Zheng (2001), 2

- H. G. Creel: "The Role of the Horse in Chinese History", The American Historical Review, Vol. 70, No. 3 (1965), pp. 647-672 (649f.)

- Frederic E. Wakeman: The great enterprise: the Manchu reconstruction of imperial order in seventeenth-century China, Vol. 1 (1985), ISBN 9780520048041, p. 77

- Griffith (2006), 1

- ^ Griffith (2006), 21-27

- ^ Li and Zheng (2001), 212

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1134

- Griffith (2006), 59

- Griffith (2006), 23-24

- Griffith (2006), 49-61

- New Scientist. Reed Business Information. Nov 16, 1978. p. 539. ISBN ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Griffith (2006), 55

- Graff (2002), 22

- Cotterell, Maurice. (2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Rochester: Bear and Company. ISBN 159143033X. Page 102.

- J. C. McVeigh (1984). Energy around the world: an introduction to energy studies, global resources, needs, utilization. Pergamon Press. p. 24. ISBN 0080316506. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Zhewen Luo (1993). China's imperial tombs and mausoleums. p. 44. ISBN 7119016199. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Text "publisherForeign Languages Press" ignored (help) - Jacques Guertin, James Alan Jacobs, Cynthia P. Avakian, (2005). Chromium (VI) Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 7–11. ISBN 9781566706087.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eric C. Rolls (1996). Citizens: flowers and the wide sea ; continuing the epic story of China's centuries-old relationship with Australia. University of Queensland Press. p. 318. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Eric C. Rolls (1996). Citizens: flowers and the wide sea ; continuing the epic story of China's centuries-old relationship with Australia. University of Queensland Press. p. 398. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Li and Zheng(2001), 212-247

- Li and Zheng (2001), 247-249

- Ebrey (1999), 61

- Ebrey (1999), 62-63.

- ^ Li and Zheng (2001), 428-434

- Li and Zheng (2001), 648-649

- Ebrey(1999), 63

- Li and Zheng (2001), 554

- Ebrey (1999), 76

- Ji et al (2005), Vol 2, 19

- Ebrey (1999), 92

- Li and Zheng (2001), 822

- Li and Zheng (2001), 859

- Li and Zheng (2001), 868

- Li and Zheng (2001), 877

- ^ Ji et al (2005), Vol 2, 84

- James P. Delgado (2008). Khubilai Khan's lost fleet: in search of a legendary armada. University of California Press. p. 72. ISBN 0520259769. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Stephen Turnbull (2003). Genghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190-1400. Osprey Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 1841765236. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Paul E. Chevedden: "Black Camels and Blazing Bolts: The Bolt-Projecting Trebuchet in the Mamluk Army", Mamluk Studies Review Vol. 8/1, 2004, pp.227-277 (232f.)

- Ebrey (1999), 140

- Ji et al (2005), Vol 3, 25

- Li and Zheng (2001), 950

- Donald F. Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe: A Century of Advance : East Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 1821. ISBN 0226467694. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Rev. WM. Campbell: "Formosa under the Dutch. Described from contemporary Records with Explanatory Notes and a Bibliography of the Island", originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London 1903, republished by SMC Publishing Inc. 1992, ISBN 957-638-083-9, p. 452

- Rev. WM. Campbell: "Formosa under the Dutch. Described from contemporary Records with Explanatory Notes and a Bibliography of the Island", originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London 1903, republished by SMC Publishing Inc. 1992, ISBN 957-638-083-9, p. 450f.

- Donald F. Lach, Edwin J. Van Kley (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe: A Century of Advance : East Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 1821. ISBN 0226467694. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Andrade, Tonio. "How Taiwan Became Chinese Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century Chapter 11 The Fall of Dutch Taiwan". Columbia University Press. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Lynn A. Struve (1998). Voices from the Ming-Qing cataclysm: China in tigers' jaws. Yale University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0300075537. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - Rev. WM. Campbell: "Formosa under the Dutch. Described from contemporary Records with Explanatory Notes and a Bibliography of the Island", originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London 1903, republished by SMC Publishing Inc. 1992, ISBN 957-638-083-9, p. 421

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. China Branch (1895). Journal of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society for the year ..., Volumes 27-28. The Branch. p. 44. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North-China Branch (1894). Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volumes 26-27. The Branch. p. 44. Retrieved 2010-6-28.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Li and Zheng (2001), 1018

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1082

- Li and Zheng (2001), 1133

- Griffith (2006), 67

- Griffith (2006), 65

- ^ Griffith (2006), 63

- ^ Griffith (2006), 62

- Griffith (2006), 64

- Griffith (2006), 106

- Li and Zheng (2001), 288

- Li and Zheng (2001), 531

- Temple (1986), 248

- Temple (1986), 215, 229

- Griffith (2006), 24

- Griffith (2006), 122

Sources

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6 (hardback); ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ji, Jianghong et al. (2005). Template:Zh icon Encyclopedia of China History Vol 1. Beijing publishing house. ISBN 7-900321-54-3.

- Ji, Jianghong et al. (2005). Template:Zh icon Encyclopedia of China History Vol 2. Beijing publishing house. ISBN 7-900321-54-3.

- Ji, Jianghong et al. (2005). Template:Zh icon Encyclopedia of China History Vol 3. Beijing publishing house. ISBN 7-900321-54-3.

- Li, Bo and Zheng Yin. (Chinese) (2001). 5000 years of Chinese history. Inner Mongolian People's publishing corp. ISBN 7-204-04420-7.

- Graff, Andrew David. (2002) Medieval Chinese Warfare: 200-900. Routledge.

- Sun, Tzu, The Art of War, Translated by Sam B. Griffith (2006), Blue Heron Books, ISBN 1-897035-35-7.

- Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 years of science, discovery and invention. Introduction by Joseph Needham. Simon & Schuster Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2.

External links

- Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery and Siege Weapons of Antiquity - An Illustrated History

- "Military Technology" Visual Sourcebook for Chinese Civilization (University of Washington)

| Science and technology in China | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Education | |

| People | |

| Institutes and programs | |