| Revision as of 10:11, 30 April 2024 editCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,453,961 edits Added bibcode. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Hydrology | #UCB_Category 277/354← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:55, 3 July 2024 edit undoKillviconiborki (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users879 editsmNo edit summaryTag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| ], one of the most saline lakes outside of Antarctica]] | ], one of the most saline lakes outside of Antarctica]] | ||

| {{water salinity}}A '''hypersaline lake''' is a landlocked ] that contains significant ]s of ], ]s, and other ], with ] levels surpassing |

{{water salinity}}A '''hypersaline lake''' is a landlocked ] that contains significant ]s of ], ]s, and other ], with ] levels surpassing those of ] (3.5%, i.e. {{convert|35|g/L|lb/USgal|disp=or}}). | ||

| Specific microbial species can thrive in high-salinity environments<ref name=Hammer1986/> that are inhospitable to most lifeforms,<ref name=Vreeland/> including some that are thought to contribute to the colour of ]s.<ref name=cassella>{{cite web | last=Cassella | first=Carly | title=How an Australian lake turned bubble-gum pink | website=Australian Geographic | date=13 December 2016 | url=https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/science-environment/2016/12/australias-pink-lakes/ | access-date=22 January 2022}}</ref><ref name=ie2018>{{cite web | last=McFadden | first=Christopher | title=Lake Hillier: Australia's Pink Lake and the Story Behind It | website=Interesting Engineering | date=24 July 2018 | url=https://interestingengineering.com/lake-hillier-australias-pink-lake-and-the-story-behind-it | access-date=22 January 2022}}</ref> Some of these species enter a dormant state when ], and some species are thought to survive for over 250 million years.<ref name=Vreeland/> | Specific microbial species can thrive in high-salinity environments<ref name=Hammer1986/> that are inhospitable to most lifeforms,<ref name=Vreeland/> including some that are thought to contribute to the colour of ]s.<ref name=cassella>{{cite web | last=Cassella | first=Carly | title=How an Australian lake turned bubble-gum pink | website=Australian Geographic | date=13 December 2016 | url=https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/science-environment/2016/12/australias-pink-lakes/ | access-date=22 January 2022}}</ref><ref name=ie2018>{{cite web | last=McFadden | first=Christopher | title=Lake Hillier: Australia's Pink Lake and the Story Behind It | website=Interesting Engineering | date=24 July 2018 | url=https://interestingengineering.com/lake-hillier-australias-pink-lake-and-the-story-behind-it | access-date=22 January 2022}}</ref> Some of these species enter a dormant state when ], and some species are thought to survive for over 250 million years.<ref name=Vreeland/> | ||

| The water |

The water in hypersaline lakes has great ] due to its high salt content.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Team|first=How It Works|date=2014-04-10|title=Can you float in the Great Salt Lake?|url=https://www.howitworksdaily.com/can-you-float-in-the-dead-sea/|access-date=2020-10-08|website=How It Works|language=en-GB}}</ref> | ||

| Hypersaline lakes are found on every continent, especially in ] or ].<ref name=Hammer1986/> | Hypersaline lakes are found on every continent, especially in ] or ].<ref name=Hammer1986/> | ||

Revision as of 21:55, 3 July 2024

Landlocked body of water that contains concentrations of salts greater than the sea

| Part of a series on |

| Water salinity |

|---|

|

| Salinity levels |

|

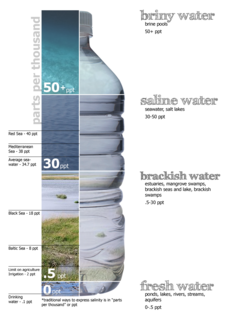

Fresh water (< 0.05%) Brackish water (0.05–3%) Saline water (3–5%) Brine (> 5% up to 26%–28% max) |

| Bodies of water |

A hypersaline lake is a landlocked body of water that contains significant concentrations of sodium chloride, brines, and other salts, with saline levels surpassing those of ocean water (3.5%, i.e. 35 grams per litre or 0.29 pounds per US gallon).

Specific microbial species can thrive in high-salinity environments that are inhospitable to most lifeforms, including some that are thought to contribute to the colour of pink lakes. Some of these species enter a dormant state when desiccated, and some species are thought to survive for over 250 million years.

The water in hypersaline lakes has great buoyancy due to its high salt content.

Hypersaline lakes are found on every continent, especially in arid or semi-arid regions.

In the Arctic, the Canadian Devon Ice Cap contains two subglacial lakes that are hypersaline. In Antarctica, there are larger hypersaline water bodies, lakes in the McMurdo Dry Valleys such as Lake Vanda with salinity of over 35% (i.e. 10 times as salty as ocean water).

The most saline water body in the world is the Gaet'ale Pond, located in the Danakil Depression in Afar, Ethiopia. The water of Gaet'ale Pond has a salinity of 43%, making it the saltiest water body on Earth (i.e. 12 times as salty as ocean water). Previously, it was considered that the most saline lake outside of Antarctica was Lake Assal, in Djibouti, which has a salinity of 34.8% (i.e. 10 times as salty as ocean water). Probably the best-known hypersaline lakes are the Dead Sea (34.2% salinity in 2010) and the Great Salt Lake in the state of Utah, US (5–27% variable salinity). The Dead Sea, dividing Israel and the West Bank from Jordan, is the world's deepest hypersaline lake. The Great Salt Lake, while having nearly three times the surface area of the Dead Sea, is shallower and experiences much greater fluctuations in salinity. At its lowest recorded water levels, it approaches 7.7 times the salinity of ocean water, but when its levels are high, its salinity drops to only slightly higher than that of the ocean.

See also

- Brine pool – Accumulation of brine in a seafloor depression

- Halocline – Stratification of a body of water due to salinity differences

- Halophile – organism that thrives in high salt concentrations

- List of bodies of water by salinity

- Pink lake

- Salt lake – one with a concentration of salts and minerals significantly higher than most lakes

Lakes portal

Lakes portal

References

- ^ Hammer, Ulrich T. (1986). Saline lake ecosystems of the world. Springer. ISBN 90-6193-535-0.

- ^ Vreeland, R.H.; Rosenzweig, W.D. & Powers, D.W. (2000). "Isolation of a 250 million-year-old halotolerant bacterium from a primary salt crystal". Nature. 407 (6806): 897–900. Bibcode:2000Natur.407..897V. doi:10.1038/35038060. PMID 11057666. S2CID 9879073.

- Cassella, Carly (13 December 2016). "How an Australian lake turned bubble-gum pink". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- McFadden, Christopher (24 July 2018). "Lake Hillier: Australia's Pink Lake and the Story Behind It". Interesting Engineering. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Team, How It Works (2014-04-10). "Can you float in the Great Salt Lake?". How It Works. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- Muzyka, Kyle (11 April 2018). "Super salty lakes discovered in Canadian Arctic could provide window into life beyond Earth". CBC News. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Perez, Eduardo; Chebude, Yonas (April 2017). "Chemical Analysis of Gaet'ale, a Hypersaline Pond in Danakil Depression (Ethiopia): New Record for the Most Saline Water Body on Earth". Aquatic Geochemistry. 23 (2): 109–117. Bibcode:2017AqGeo..23..109P. doi:10.1007/s10498-017-9312-z. S2CID 132715553.

- Quinn, Joyce A.; Woodward, Susan L., eds. (2015). Earth's Landscape: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-61069-446-9.

- Wilkerson, Christine. "Utah's Great Salt Lake and Ancient Lake Bonneville, PI39 – Utah Geological Survey". Geology.utah.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-08-15. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- Allred, Ashley; Baxter, Bonnie. "Microbial life in hypersaline environments". Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- Kjeldsen, K.U.; Loy, A.; Jakobsen, T.F.; Thomsen, T.R.; et al. (May 2007). "Diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria from an extreme hypersaline sediment, Great Salt Lake (Utah)". FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 60 (2): 287–298. Bibcode:2007FEMME..60..287K. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00288.x. PMID 17367515.