| Revision as of 12:31, 17 January 2016 view source31.219.124.159 (talk) We don't use honorifics in Misplaced Pages← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:47, 18 January 2025 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,453,931 edits Altered pages. Formatted dashes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Miracle workers | #UCB_Category 97/192 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Christian apostle and missionary}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Saint Paul}} | |||

| {{redirect|Saint Paul}} | |||

| {{religious text primary|date=September 2015}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Christian leader | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2023}} | |||

| | name = Paul | |||

| {{Infobox saint | |||

| | honorific-prefix = | |||

| |honorific_prefix = ] | |||

| | birth_date = {{circa}} AD 5<ref>. PBS. Retrieved 2010–11–19.</ref> | |||

| |name = Paul the Apostle | |||

| | death_date = {{circa}} AD 67<ref name="Harris" >Harris, Stephen L. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. ISBN 978-1-55934-655-9</ref> | |||

| |image = Rubens apostel paulus grt.jpg | |||

| | birth_name = Saul of Tarsus<ref name=EB>{{cite web|url=http://global.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/447019/Saint-Paul-the-Apostle|title=Saint Paul, the Apostle, original name Saul of Tarsus from ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition|publisher=global.britannica.com|accessdate=July 2014 }}</ref><ref name="acts0911" /><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.biblestudytools.com/encyclopedias/condensed-biblical-encyclopedia/saul-of-tarsus.html|title=Saul of Tarsus|publisher=biblestudytools.com|accessdate=July 2014}}</ref> | |||

| |caption = ''Saint Paul'' ({{circa|1611}}) by ] | |||

| | image = Bartolomeo Montagna - Saint Paul - Google Art Project.jpg | |||

| |major_shrine = ], ], Italy | |||

| | caption = ''Saint Paul'' by ] | |||

| |titles = Apostle to the Gentiles, Martyr | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ]<ref name="2Acts22:3">{{Bibleref2|Acts|22:3}}</ref>→ | |||

| |birth_name = Saul of Tarsus | |||

| | death_place = probably in ], Roman Empire<ref name="Harris" /> | |||

| |birth_date = {{c.|5 AD}}<ref name="pbs.org" /> | |||

| | feast_day = January 25 (The Conversion of Paul)<br />February 10 (Feast of Saint Paul's Shipwreck in ])<br />June 29 (])<br/>June 30 (former solo feast day, still celebrated by some religious orders) <br />November 18 (Feast of the dedication of the ]s of Saints Peter and Paul) | |||

| |birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | venerated_in = All ] | |||

| |death_date = {{c.|64/65 AD}}{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=436}}{{sfn|Harris|2003|p=42|ps=: He was probably martyred in Rome about 64–65 AD}} | |||

| | title = Apostle of the heathen | |||

| |death_place = ], ], Roman Empire{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=436}}{{sfn|Harris|2003}} | |||

| | canonized_by = ] | |||

| |venerated_in = All ] that venerate ] | |||

| | attributes = ] | |||

| |feast_day = {{plainlist| | |||

| | patronage = Missions; Theologians; Gentile Christians | |||

| * 25 January – ] | |||

| | major_shrine = ] | |||

| * 10 February – Feast of Saint Paul's Shipwreck in ] | |||

| * 29 June – ] (with ]) | |||

| * 30 June – Former solo feast day, still celebrated by some religious orders | |||

| * 18 November – Feast of the dedication of the ]s of Saints Peter and Paul | |||

| * Saturday before the sixth Sunday after Pentecost – Feast of the ] and Paul the thirteenth Apostle (])<ref>''Domar: the calendrical and liturgical cycle of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church'', Armenian Orthodox Theological Research Institute, 2003, p. 446.</ref>}} | |||

| |canonized_by = | |||

| |canonized_date = ] | |||

| |canonized_place = | |||

| |attributes= ], ], book | |||

| |suppressed_date = | |||

| |patronage = Missionaries, theologians, ], and ], Malta | |||

| |module = {{Infobox theologian | |||

| | embed=yes | |||

| | notable_works = {{ubl|'''Certain:'''|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|'''Disputed:'''|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| | tradition_movement = ] | |||

| | language = ] | |||

| | occupation = ]ary and preacher | |||

| | main_interests = ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | notable_ideas = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | education = School of ]<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|22:3|NRSV}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Paul |

'''Paul'''{{efn|{{langx|la|Paulus}}; {{langx|grc-x-koine|Παῦλος|translit=Paûlos}}; {{langx|cop|ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ}}; {{langx|he|פאולוס השליח}}}} also named '''Saul of Tarsus''',{{efn|]: שאול ܫܐܘܠ, <small>romanized</small>: ''Šāʾūl''}} commonly known as '''Paul the Apostle'''{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=442}} and '''Saint Paul''',{{sfn|Sanders|2019}} was a ] ({{circa|5|64/65}} AD) who spread the ] of ] in the ].{{sfn|Powell|2009}} For his contributions towards the ], he is generally regarded as one of the most important figures of the ],{{sfn|Sanders|2019}}{{sfn|Dunn|2001|loc=Ch 32|p=577}} and he also founded ] from the mid-40s to the mid-50s AD.{{sfn|Rhoads|1996|p=39}} | ||

| The main source of information on Paul's life and works is the ] in the ]. Approximately half of its content documents his travels, preaching and ]s. Paul was not one of the ], and did not know Jesus during his lifetime. According to the Acts, Paul lived as a ] and participated in the ] of early ] of Jesus, possibly ] diaspora Jews converted to Christianity,{{sfn|Dunn|2009|pp=345–346}} in the area of ], before ].{{refn|group=note|name="persecution"}} Some time after having approved of the execution of ],<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|8:1|ESV}}</ref> Paul was traveling on the road to ] so that he might find any Christians there and bring them "bound to Jerusalem".<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:2|ESV}}</ref> At midday, a light brighter than the sun shone around both him and those with him, causing all to fall to the ground, with the ] verbally addressing Paul regarding his persecution in a vision.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|26:13–20|ESV}}</ref><ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|22:7–9|ESV}}</ref> Having been made blind,<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|22:11|ESV}}</ref> along with being commanded to enter the city, his sight was restored three days later by ]. After these events, Paul was baptized, beginning immediately to proclaim that Jesus of Nazareth was the ] and the ].<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:3–22|ESV}}</ref> He made three missionary journeys to spread the Christian message to non-Jewish communities in ], the Greek provinces of ], ], and ], as well as ] and ], as narrated in the Acts. | |||

| According to writings in the ] Paul, who was originally called Saul, was dedicated to the ] of the early ] of Jesus in the area of ].<ref> | |||

| Acts 8:1 "at Jerusalem"; Acts 9:13 "at Jerusalem"; Acts 9:21 "in Jerusalem"; Acts 26:10 "in Jerusalem". | |||

| </ref> In the narrative of the book of ], while Paul was traveling on the road from Jerusalem to ] on a mission to "bring them which were there bound unto Jerusalem", the ] appeared to him in a great light. He was struck blind, but after three days his sight was restored by ], and Paul began to preach that Jesus of Nazareth is the ] and the ].<ref>Acts 9:20 And straightway he preached Christ in the synagogues, that he is the Son of God.<br/>Acts 9:21 But all that heard ''him'' were amazed, and said; Is not this he that destroyed them which called on this name in Jerusalem, and came hither for that intent, that he might bring them bound unto the chief priests?</ref> Approximately half of the book of Acts deals with Paul's life and works. | |||

| Fourteen of the |

Fourteen of the 27 books in the New Testament have traditionally been attributed to Paul.{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=407}} Seven of the ] are undisputed by scholars as being ], with varying degrees of argument about the remainder. Pauline ] is not asserted in the Epistle itself and was already doubted in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.{{refn|group=note|] knew the Letter to the Hebrews as being "under the name of Barnabas" (''De Pudicitia'', chapter 20 where Tertullian quotes Hebrews 6:4–8); Origen, in his now lost ''Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews'', is reported by Eusebius<ref name=EcclHist_VI.25 /> as having written "if any Church holds that this epistle is by Paul, let it be commended for this. For not without reason have the ancients handed it down as Paul's. But who wrote the epistle, in truth, God knows. The statement of some who have gone before us is that Clement, bishop of the Romans, wrote the epistle, and of others, that Luke, the author of the Gospel and the Acts, wrote it}} It was almost unquestioningly accepted from the 5th to the 16th centuries that Paul was the author of Hebrews,{{sfn|Brown|Fitzmyer|Murphy|1990|p=920, col.2|loc=Ch 60:2}} but that view is now almost universally rejected by scholars.{{sfn|Brown|Fitzmyer|Murphy|1990|p=920, col.2|loc=Ch 60:2}}{{sfn|Kümmel|1975|pp=392–94, 401–03}} The other six are believed by some scholars to have come from followers writing in his name, using material from Paul's surviving letters and letters written by him that no longer survive.{{sfn|Powell|2009}}{{sfn|Sanders|2019}}{{refn|group=note|Paul's undisputed epistles are 1 Thessalonians, Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Philippians, and Philemon. The six letters believed by some to have been written by Paul are Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus.<ref name="umc.org"/>}} Other scholars argue that the idea of a pseudonymous author for the disputed epistles raises many problems.{{sfn|Carson|Moo|2009}} | ||

| Today, Paul's epistles continue to be vital roots of the theology, worship |

Today, Paul's epistles continue to be vital roots of the theology, worship and ] life in the ] and Protestant traditions ], as well as the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox traditions ].{{sfn|Aageson|2008|p=1}} Paul's influence on Christian thought and practice has been characterized as being as "profound as it is pervasive", among that of many other apostles and ] involved in the spread of the Christian faith.{{sfn|Powell|2009}} | ||

| Christians, notably in the ] tradition, have classically read Paul as advocating for a law-free Gospel against Judaism. Polemicists and scholars likewise, especially during the early 20th century, have alleged that Paul corrupted or hijacked ], often by introducing pagan or Hellenistic themes to the early church.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} There has since been increasing acceptance of ] in line with the original disciples in ] over past misinterpretations, manifested through movements like "Paul Within Judaism".<ref>{{cite book |last=Thiessen |first=Matthew |year=2023 |title=A Jewish Paul |publisher=Baker Academic |pages=4–10 |isbn=978-1540965714}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Fredriksen |first=Paula |author-link=Paula Fredriksen |year=2018 |title=Paul: The Pagans' Apostle |publisher=] |isbn=978-0300240153}}</ref>{{sfn|Hurtado|2005|p=160}} | |||

| == Available sources == | |||

| {{further|Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles}} | |||

| ]'', ] by ], 1542–45]] | |||

| The main source for information about Paul's life is the material found in his epistles and in the ]. However, the epistles contain little information about Paul's past. The book of Acts recounts more information but leaves several parts of Paul's life out of its narrative, such as his probable but undocumented execution in Rome.<ref name="ODCC self">"Paul, St", Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005</ref> Acts also contradicts Paul's epistles on multiple accounts, in particular concerning the frequency of Paul's visits to the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Introduction to the New Testament History and Literature — 5. The New Testament as History |url=http://oyc.yale.edu/religious-studies/rlst-152/lecture-5 |publisher=Yale University |website=Open Yale Courses |year=2009 |first=Dale B. |last=Martin}}</ref> | |||

| Sources outside the New Testament that mention Paul include: | |||

| * ]'s ] (late 1st/early 2nd century); | |||

| * ]'s letter ] (early 2nd century); | |||

| * ]'s ] (early 2nd century); | |||

| * The 2nd-century document '']''. | |||

| == Names == | == Names == | ||

| ] ({{circa|1657}})|left]] | |||

| Although it has been popularly assumed that his name was changed when he converted from Judaism to Christianity, that is not the case.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Marrow|first1=Stanley B.|title=Paul: His Letters and His Theology : an Introduction to Paul's Epistles|date=1 Jan 1986|publisher=Paulist Press|isbn=978-0809127443|pages=5, 7|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RPu1qx50HmgC&pg=PA5#v=onepage&q=%22The%20name%20of%20saul%20paul%22&f=false|accessdate=31 August 2014}}</ref><ref name=CathAns>{{cite web|title=Why did God change Saul's name to Paul?|url=http://www.catholic.com/quickquestions/why-did-god-change-sauls-name-to-paul|website=Catholic Answers|accessdate=31 August 2014}}</ref> His Jewish name was "Saul" ({{Hebrew Name|שָׁאוּל|Sha'ul|Šāʼûl|"asked for, prayed for, borrowed"}}), perhaps after the biblical ], a fellow ] and the first king of Israel. According to the Book of Acts, he inherited Roman citizenship from his father. As a Roman citizen, he also bore the ] of "Paul" —in ]: Παῦλος (''Paulos''),<ref>Greek lexicon <br/>Greek lexicon <br/>Hebrew lexicon </ref> and in Latin: Paulus.<ref>'''Paulus''' autem et Barnabas demorabantur Antiochiae docentes et evangelizantes cum aliis pluribus verbum Domini</ref>{{Bibleref2c|Acts|16:37}} {{Bibleref2c-nb|Acts|22:25-28}} It was quite usual for the Jews of that time to have two names, one Hebrew, the other Latin or Greek.<ref name=Prat>Prat, Ferdinand. . The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 2 Apr. 2013.</ref><ref>Oxford University Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary, ISBN 0198642016, entry for Paulus: "a Roman surname (not a praenomen;"</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.se/books?isbn=0802804780 |title=The Letter of Paul to the Galatians: An Introduction|publisher=books.google.se|accessdate=2014}}</ref> | |||

| Paul's Jewish name was "Saul" ({{Hebrew name|שָׁאוּל|Sha'ûl|Šā'ûl}}), perhaps after the biblical ], the first ] and, like Paul, a member of the ]; the Latin name Paulus, meaning small, was not a result of his conversion as is commonly believed but a second name for use in communicating with a Greco-Roman audience.{{sfn|Dunn|2003|p=21}}<ref> | |||

| a. {{cite book|last1=Marrow|first1=Stanley B.|title=Paul: His Letters and His Theology : an Introduction to Paul's Epistles|year=1986|publisher=Paulist Press|isbn=978-0809127443|pages=5, 7|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RPu1qx50HmgC&pg=PA5}} | |||

| <br />b. {{cite web|title=Why did God change Saul's name to Paul?|url=http://www.catholic.com/quickquestions/why-did-god-change-sauls-name-to-paul|website=Catholic Answers|access-date=31 August 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121030000303/http://www.catholic.com/quickquestions/why-did-god-change-sauls-name-to-paul|archive-date=30 October 2012}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ], he was a ].<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|22:25–29|9}}</ref> As such, he bore the ] {{lang|la|Paulus}}, which translates in ] as {{lang|grc|Παῦλος}} ({{transliteration|grc|Paulos}}).<ref name="Strong" /><ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|16:37|9}}, {{Bibleverse-nb|Acts|22:25–289}}</ref> It was typical for the Jews of that time to have two names: one Hebrew, the other Latin or Greek.{{sfn|Prat|1911}}{{sfn|Lewis|Short|1879|loc=Paulus: "a Roman surname (not a praenomen;)"}}{{sfn|Cole|1989}} | |||

| In the book of Acts, when he had the vision which led to his conversion on the ], ] called him "Saul, Saul",<ref>{{bibleref2|Acts|9:4;22:7;26:14||9|Acts 9:4; 22:7; 26:14}}</ref> in "the Hebrew tongue".<ref>{{bibleref2|Acts|26:14|9}} Note: This is the only place in the Bible where the reader is told what language Jesus was speaking.</ref> Later, in a vision to ], "the Lord" referred to him as "Saul, of Tarsus".<ref name="acts0911">{{bibleref2|Acts|9:11|9}} This is the place where the expression "" comes from.</ref> When Ananias came to restore his sight, he called him "Brother Saul".<ref>{{bibleref2|Acts.9:17;22:13||9|Acts 9:17; 22:13}}</ref> | |||

| Jesus called him "Saul, Saul"<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|9:4; 22:7; 26:14|9}}</ref> in "the Hebrew tongue" in the Acts of the Apostles, when he had the vision which led to ] on the road to Damascus.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|26:14|9}}</ref> Later, in a vision to ], "the Lord" referred to him as "Saul, of Tarsus".<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|9:11|9}}</ref> When Ananias came to restore his sight, he called him "Brother Saul".<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|9:17; 22:13}}</ref> | |||

| In {{Bibleref2|Acts|13:9}}, Saul is called "Paul" for the first time on the island of ] — much later than the time of his conversion. The author ("]") indicates the names were interchangeable: "...Saul, who also is called Paul...". He thereafter refers to him as Paul, apparently Paul's preference since he is called Paul in all other Bible books where he is mentioned, including those he authored. Adopting his Roman name was typical of Paul's missionary style. His method was to put people at their ease and to approach them with his message in a language and style to which they could relate as in 1 Cor 9:19-23.<ref name=CathAns/> | |||

| In ], Saul is called "Paul" for the first time on the island of ], much later than the time of his conversion.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|13:9|9}}</ref> The ] indicates that the names were interchangeable: "Saul, who also is called Paul." He refers to him as Paul through the remainder of Acts. This was apparently Paul's preference since he is called Paul in all other Bible books where he is mentioned, including ]. Adopting his Roman name was typical of Paul's missionary style. His method was to put people at ease and approach them with his message in a language and style that was relatable to them, as he did in ]{{Bibleverse|1 Corinthians|9:19–23|9|:19–23}}.<ref>{{Bibleverse|1 Corinthians|9:19–23|9}}</ref><ref name=CathAns /> | |||

| == Life == | |||

| == Available sources == | |||

| {{further|Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles}} | |||

| A native of ], the capital city in the ],<ref name="2Acts22:3" /> Paul wrote that he was "a ] born of Hebrews", a ],<ref>{{Bibleref2|Philippians|3:5}}</ref> and one who advanced in ] beyond many of his peers. He also wrote that he was "unmarried," at least as early as his writing of I Corinthians 7:8, however some hold that he may have been married prior to that, due to certain textual analyses of his writings.<ref> Textual analysis points to possible earlier marriage of Paul.</ref> His initial reaction to the newly formed Christian movement was to zealously persecute its early followers and to violently attempt to destroy the movement. ] while on the road to ] was clearly a life-altering event for him, changing him from being one of the early movement's most ardent persecutors to being one of its most fervent supporters.<ref name="Powell" /> | |||

| ]'', a ] by ] developed between 1542 and 1545]] | |||

| The main source for information about Paul's life is the material found in ] and in the Acts of the Apostles.{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=19–20}} However, the epistles contain little information about Paul's pre-conversion past. The Acts of the Apostles recounts more information but leaves several parts of Paul's life out of its narrative, such as his probable but undocumented execution in Rome.{{sfn|Cross |Livingstone|2005|loc=St Paul}} The Acts of the Apostles also appear to contradict Paul's epistles on multiple matters, in particular concerning the frequency of Paul's visits to the ].<ref name="dalemartin"/>{{sfn|Ehrman|2000|pp=262–65}} | |||

| Sources outside the New Testament that mention Paul include: | |||

| After his conversion, Paul began to preach that Jesus is the ], the ].<ref>{{Bibleref2|Acts|9:20-21|9|Acts 9:20–21}}</ref> His leadership, influence, and legacy led to the formation of communities dominated by Gentile groups that worshiped Jesus, adhered to the ], but relaxed or abandoned the ritual and dietary teachings of the ]. He taught that these laws and rituals had either been ] or were ] of Christ, though the exact relationship between ] is still disputed. Paul taught of the ] and his teaching of a ] established through ] and ]. The ] does not record Paul's death. | |||

| * ]'s ] (late 1st/early 2nd century); | |||

| * ]'s epistles to ] and to ]{{sfn|Ladeuze|1909}} (early 2nd century); | |||

| * ]'s epistle to ] (early 2nd century); | |||

| * ]'s {{lang|la|]}} (early 4th century); | |||

| * The ] narrating the life of Paul (], ], ]), the apocryphal epistles attributed to him (the Latin ], the ], and the ]) and some ] attributed to him (] and ]). These writings are all later, usually dated from the 2nd to the 4th century. | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| === Early life === | === Early life === | ||

| ] to ]]] | ] to ]]] | ||

| The two main sources of information that give access to the earliest segments of Paul's career are the Acts of the Apostles and the autobiographical elements of Paul's letters to the early Christian communities.{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=19–20}} Paul was likely born between the years of 5 BC and 5 AD.{{sfn|White|2007|pp=145–47}} The Acts of the Apostles indicates that Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, but ] took issue with the evidence presented by the text.{{sfn|Koester|2000|p=107}}<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|16:37}},{{Bibleverse|Acts|22:25–29}}</ref> Some have suggested that Paul's ancestors may have been freedmen from among the thousands of Jews whom ] took as slaves ], which would explain how he was born into ], as slaves of Roman citizens gained citizenship upon emancipation.<ref>John B. Polhill, 532; cf. Richard R. Losch, ''The Uttermost Part of the Earth: A Guide to Places in the Bible'' (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2005), 176–77.</ref> | |||

| He was from a devout Jewish family{{sfn|Wright|1974|p=404}} based in the city of ], which had been made part of the ] by the time of Paul's adulthood.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-07-22 |title=Saint Paul the Apostle {{!}} Biography & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Paul-the-Apostle#:~:text=Paul%20was%20a%20Greek-speaking,in%20his%20life%20and%20letters. |access-date=2024-08-28 |website=britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> Tarsus was of the larger centers of trade on the Mediterranean coast and renowned for its ], it had been among the most influential cities in ] since the time of ], who died in 323 BC.{{sfn|Wright|1974|p=404}} | |||

| The two main sources of information by which we have access to the earliest segments of Paul's career are the Bible's Book of Acts and the autobiographical elements of Paul's letters to the early church communities. Paul was likely born between the years of 5 BC and 5 AD.<ref name=White2007>{{cite book|last=White|first=L. Michael|title=From Jesus to Christianity|year=2007|publisher=HarperSanFrancisco|location=San Francisco|isbn=0060816104|pages=145–147|edition=3rd impr.}}</ref> The Book of Acts indicates that Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, more affirmatively describing his father as such, but some scholars have taken issue with the evidence presented by the text.<ref>{{cite book|last=Koester|first=Helmut|title=Introduction to the New Testament|year=2000|publisher=de Gruyter|location=New York|isbn=3110149702|page=107|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=thXUHM5udTcC&pg=107#v=onepage&q&f=false|edition=2|accessdate=14 June 2013}}</ref>{{Bibleref2c|Acts|16:37}}{{Bibleref2c|Acts|22:25-29}} | |||

| Paul referred to himself as being "of the stock of Israel, of the ], a Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a ]".<ref>{{Bibleverse|Philippians|3:5}}</ref>{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=21–22}} The Bible reveals very little about Paul's family. Acts quotes Paul referring to his family by saying he was "a Pharisee, born of Pharisees".<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|23:6}}</ref>{{sfn|Dunn|2003|p=22}} Paul's nephew, his sister's son, is mentioned in Acts 23:16.<ref name="auto1">{{Bibleverse|Acts|23:16}}</ref> In Romans 16:7, he states that his relatives, ] and ], were Christians before he was and were prominent among the Apostles.<ref name="Bibleref2|Romans|16:7">{{Bibleverse|Romans|16:7}}</ref> | |||

| He was from a devout Jewish family<ref name="Wright404" /> in the city of ]–one of the largest trade centers on the Mediterranean coast.<ref>Montague, George T. ''The Living Thought Of St. Paul'' Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Co. 1966. AISN: B0006CRKIC</ref> It had been in existence several hundred years prior to his birth. It was renowned for its university. During the time of ], who died in 323 BC, Tarsus was the most influential city in ].<ref name="Wright404">Wright, G. Ernest , ''Great People of the Bible and How They Lived'', (Pleasantville, New York: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc., 1974). ASIN: B000OEOKL2</ref><!-- Additional material in Wallace below --> | |||

| The family had a history of religious piety.<ref>{{Bibleverse|2 Timothy|1:3}}</ref>{{refn|group=note|name="disputed"|1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus may be "Trito-Pauline", meaning they may have been written by members of the Pauline school a generation after his death.}} Apparently, the family lineage had been very attached to ] and observances for generations.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Philippians|3:5–6}}</ref> Acts says that he was an artisan involved in the leather crafting or tent-making profession.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|18:1–3}}</ref>{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=41–42}} This was to become an initial connection with ], with whom he would partner in tentmaking<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|18:3}}</ref> and later become very important teammates as fellow missionaries.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Romans|16:4}}</ref> | |||

| Paul referred to himself as being "of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a ]".{{Bibleref2c|Phil.|3:5}} | |||

| While he was still fairly young, he was sent to Jerusalem to receive his education at the school of ],<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|22:3}}</ref>{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=21–22}} one of the most noted teachers of ] in history. Although modern scholarship accepts that Paul was educated under the supervision of Gamaliel in Jerusalem,{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=21–22}} he was not preparing to become a scholar of Jewish law, and probably never had any contact with the ] school.{{sfn|Dunn|2003|pp=21–22}} Some of his family may have resided in Jerusalem since later the son of one of his sisters saved his life there.<ref name="auto1"/>{{sfn|Dunn|2003|p=21}} Nothing more is known of his biography until he takes an active part in the martyrdom of ],<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|7:58–60; 22:20}}</ref> a Hellenised diaspora Jew.{{sfn|Dunn|2009|pp=242–44}} | |||

| The Bible reveals very little about Paul's family. Paul's nephew, his sister's son, is mentioned in {{bibleref2|Acts|23:16}}. Acts also quotes Paul referring to his father by saying he, Paul, was "a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee" ({{Bibleref2|Acts|23:6}}). Paul refers to his mother in {{bibleref2|Romans|16:13}} as among those at Rome. In {{Bibleref2|Romans|16:7}} he states that his relatives, ] and ], were Christians before he was and were prominent among the apostles. | |||

| Some modern scholarship argues that while Paul was fluent in ], the language he used to write his letters, his first language was probably ].{{sfn|Bruce|2000|p=43}} In his letters, Paul drew heavily on his knowledge of ], using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile converts in their understanding of the Gospel and to explain his Christology.{{sfn|Lee|2006|pp=13–26}}{{sfn|Kee|1983|p=208}} | |||

| The family had a history of religious piety ({{Bibleref2|2Tim|1:3||2 Timothy 1:3}}) <ref name="disputed">1st Timothy, 2nd Timothy, and Titus may be "Trito-Pauline", meaning they may have been written by members of the Pauline school a generation after his death.</ref> Apparently the family lineage had been very attached to Pharisaic traditions and observances for generations.{{Bibleref2c|Philippians|3:5-6}} Acts says that he was in the tent-making profession.{{Bibleref2c|Acts|18:1-3}} This was to become an initial connection with ] with whom he would partner in tentmaking{{Bibleref2c|Acts|18:3}} and later become very important teammates as fellow missionaries.{{Bibleref2c|Rom.|16:4}} | |||

| ===Persecutor of early Christians=== | |||

| While he was still fairly young, he was sent to Jerusalem to receive his education at the school of ],{{Bibleref2c|Acts|22:3}} one of the most noted rabbis in history. The ] school was noted for giving its students a balanced education, likely giving Paul broad exposure to classical literature, philosophy, and ethics.<ref name="Wallace">Wallace, Quency E. "". ''The American Journal of Biblical Theology''.</ref> Some of his family may have resided in Jerusalem since later the son of one of his sisters saved his life there.{{Bibleref2c|Acts|23:16}} Nothing more is known of his background until he takes an active part in the martyrdom of ].{{Bibleref2c|Acts|7:58-60;22:20}} Paul confesses that "beyond measure" he persecuted the church of God prior to his conversion.{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:13-14}} {{Bibleref2c|Phil.|3:6}} {{Bibleref2c|Acts|8:1-3}} Although we know from his biography and from Acts that Paul could speak Hebrew, modern scholarship suggests that ] was his first language.<ref>Frederick Fyvie Bruce (1977), ''Paul, Apostle of the Heart Set Free'', p. 43</ref><ref>] 2009. ''Introduction to New Testament History and Literature'', lecture 14 . ].</ref> | |||

| ]'', a 1601 portrait by ]]] | |||

| Paul says that before ],<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:13–14}}, {{Bibleverse|Philippians|3:6}}, {{Bibleverse|Acts|8:1–3}}</ref> he persecuted early Christians "beyond measure", more specifically Hellenised diaspora Jewish members who had returned to the area of ].{{sfn|Dunn|2009|pp=246–47, 277}}{{refn|group=note|name="persecution"|Acts 8:1 "at Jerusalem"; Acts 9:13 "at Jerusalem"; Acts 9:21 "in Jerusalem"; Acts 26:10 "in Jerusalem". In Galatians 1:13, Paul states that he "persecuted the church of God and tried to destroy it," but does not specify where he persecuted the church. In Galatians 1:22 he states that more than three years after his conversion he was "still unknown by sight to the churches of Judea that are in Christ," seemingly ruling out Jerusalem as the place he had persecuted Christians.<ref name="dalemartin">{{Cite web |title=Introduction to the New Testament History and Literature – 5. The New Testament as History |url=http://oyc.yale.edu/religious-studies/rlst-152/lecture-5 |website=Open Yale Courses |publisher=Yale University |year=2009 |first=Dale B. |last=Martin}}</ref>}} According to ], the Jerusalem community consisted of "Hebrews", Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and "Hellenists", Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.{{sfn|Dunn|2009|pp=246–47}} Paul's initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking "Hellenists" due to their anti-Temple attitude.{{sfn|Dunn|2009|p=277}} Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the "Hebrews" and their continuing participation in the Temple cult.{{sfn|Dunn|2009|p=277}} | |||

| ===Conversion=== | |||

| In his letters, Paul reflected heavily from his knowledge of ], using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile converts in their understanding of the revealed word of God.<ref>Kee, Howard and Franklin W. Young, ''Understanding The New Testament'', Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, Inc. 1958, pg 208. ISBN 978-0139365911</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Conversion of Paul the Apostle}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] to the movement of followers of Jesus can be dated to 31–36 AD{{sfn|Bromiley|1979|p=689}}{{sfn|Barnett|2002|p=21}}{{sfn|Niswonger|1992|p=200}} by his reference to it in one of his ]. In Galatians 1:16, Paul writes that God "was pleased to reveal his son to me."<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:16|ESV}}</ref> In 1 Corinthians 15:8, as he lists the order in which Jesus appeared to his disciples after his resurrection, Paul writes, "last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also."<ref>{{Bibleverse|1 Corinthians|15:8|NASB}}</ref> | |||

| According to the account in the Acts of the Apostles, it took place on the road to ], where he reported having experienced a ] of the ascended Jesus. The account says that "He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, 'Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?' He asked, 'Who are you, Lord?' The reply came, 'I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting'."<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts |9:4–5}}</ref> | |||

| He would also rely heavily on the training he received concerning the law and the prophets, utilizing this knowledge to convince his Jewish countrymen of the unity of past Old Testament prophecy and covenants with the fulfilling of these in Jesus Christ. His wide spectrum of experiences and education gave the "Apostle to the Gentiles"{{Bibleref2c|Rom.|1:5}} {{Bibleref2c-nb|Rom|11:13}} {{Bibleref2c|Gal.|2:8}} the tools which he later would use to effectively spread ] and to establish the church solidly in the Roman Empire.<ref name="Wallace"/> | |||

| According to the account in Acts 9:1–22, he was blinded for three days and had to be led into Damascus by the hand.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:1–22|9}}</ref> During these three days, Saul took no food or water and spent his time in prayer to God. When ] arrived, he laid his hands on him and said: "Brother Saul, the Lord, '''' Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost."<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:17}}</ref> His sight was restored, he got up and was baptized.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:18}}</ref> This story occurs only in Acts, not in the Pauline epistles.{{sfn|Aslan|2014|p=184}} | |||

| === Conversion === | |||

| {{Main|Conversion of Paul the Apostle}} | |||

| ]'' (1601), by ]]] | |||

| ] can be dated to 31–36<ref>{{Cite book | last1 = Bromiley | first1 = Geoffrey William | title = International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A – D (International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (Wbeerdmans)) | year = 1979 | publisher = Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company | location = | isbn = 0-8028-3781-6 | page = 689 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | last1 = Barnett | first1 = Paul | title = Jesus, the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times | year = 2002 | publisher = InterVarsity Press | location = | isbn = 0-8308-2699-8 | page = 21 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | last1 = L. Niswonger | first1 = Richard | title = New Testament History | year = 1993 | publisher = Zondervan Publishing Company | location = | isbn = 0-310-31201-9 | page = 200 }}</ref> by his reference to it in one of his ]. In {{Bibleref2|Galatians|1:16|ESV}} Paul writes that God "was pleased to reveal his son to me." In {{Bibleref2|1 Corinthians|15:8|NASB}}, as he lists the order in which Jesus appeared to his disciples after his resurrection, Paul writes, "last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also." | |||

| The author of the Acts of the Apostles may have learned of Paul's conversion from the ], or from the ], or possibly from Paul himself.{{sfn|McRay|2007|p=66}} | |||

| According to the account in ], it took place on the road to Damascus, where he reported having experienced a ] of the resurrected Jesus. The account says that "he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?" Saul replied, "Who art thou, Lord? And the Lord said, I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: '''' hard for thee to kick against the pricks."{{Bibleref2c|Acts|9:4-5|9}} According to the account in {{Bibleref2|Acts|9:1–22|9}}, he was blinded for three days and had to be led into Damascus by the hand. During these three days, Saul took no food or water and spent his time in prayer to God. When ] arrived, he laid his hands on him and said: "Brother Saul, the Lord, '''' Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost."{{Bibleref2c |Acts|9:17|9}} His sight was restored, he got up and was baptized.{{Bibleref2c |Acts|9:18|9}} This story occurs only in Acts, not in the Pauline epistles.<ref name=Aslan>{{cite book|last1=Aslan|first1=Reza|title=Zealot|date=2013|publisher=Random House|location=New York|isbn=978-0-8129-8148-3|page=184|edition=Paperback}}</ref> | |||

| According to Timo Eskola, early Christian theology and discourse was influenced by the Jewish ] tradition.{{sfn|Eskola|2001}} ], ] and ] have variously argued that Paul's accounts of his conversion experience and his ascent to the heavens (in ]) are the earliest first-person accounts that are extant of a Merkabah mystic in Jewish or Christian literature.{{sfn|Churchill|2010|pp=4,16-17,22-23}} Conversely, Timothy Churchill has argued that Paul's Damascus road encounter does not fit the pattern of Merkabah.{{sfn|Churchill|2010|pp=250ff.}} | |||

| The author of the Acts of the Apostles, likely learned of his conversion from Paul, from the church in Jerusalem, or from the ].<ref name="McRay66">{{cite book|last=McRay|first=John|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GvgexcfnWC0C&pg=PT66#v=onepage&q=%22Luke%20knew%20the%20story%22&f=false |title=Paul His Life and Teaching|year=2007|publisher=Baker Academic|location=Grand Rapids, MI |isbn=978-1441205742 |page=66}}</ref> | |||

| === Post-conversion === | === Post-conversion === | ||

| According to ]: | |||

| ] (1571–1610), ''The Conversion of Saint Paul'', 1600 ]] | |||

| {{Blockquote|And immediately he proclaimed Jesus in the synagogues, saying, "He is the Son of God." And all who heard him were amazed and said, "Is not this the man who made havoc in Jerusalem of those who called upon this name? And has he not come here for this purpose, to bring them bound before the chief priests?" But Saul increased all the more in strength, and confounded the Jews who lived in Damascus by proving that Jesus was the Christ.|Acts 9:20–22<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:20–22}}</ref>}} | |||

| ] c. 1657]] | |||

| {{Quote|At once he began to preach in the synagogues that Jesus is the Son of God. All those who heard him were astonished and asked, "Isn't he the man who raised havoc in Jerusalem among those who call on this name? And hasn't he come here to take them as prisoners to the chief priests?" Yet Saul grew more and more influential and baffled the Jews living in Damascus by proving that Jesus is the Messiah.|{{Bibleref2|Acts|9:20-22}}}} | |||

| In the opening verses of {{Bibleref2|Romans|1}}, Paul provides a litany of his own apostolic appointment to preach among the Gentiles{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:16}} and his post-conversion convictions about the risen Christ.<ref name="Sanders2" /> | |||

| * Paul described himself as | |||

| ** a servant of Jesus Christ; | |||

| ** having experienced an unforeseen, sudden, startling change, due to all-powerful grace—not the fruit of his reasoning or thoughts;{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:12-15|Gal. 1:12-15}} {{Bibleref2c|1cor|15:10||1 Cor. 15:10}} | |||

| ** having seen Christ as did the other apostles when Christ appeared to him{{Bibleref2c|1cor|15:8||1 Cor. 15:8}} as he appeared to Peter, to James, to the Twelve, after his Resurrection;{{Bibleref2c|1cor|9:1||1 Cor. 9:1}} | |||

| ** called to be an apostle; | |||

| ** set apart for the gospel of God. | |||

| * Paul described Jesus as | |||

| ** having been promised by God beforehand through his prophets in the holy Scriptures; | |||

| ** being the true messiah and the Son of God; | |||

| ** having biological lineage from David ("according to the flesh");{{Bibleref2c|rom|1:3||Rom. 1:3}} | |||

| ** having been declared to be the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead; | |||

| ** being Jesus Christ our Lord; | |||

| ** the One through whom we have received grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith for the sake of his name among all the nations, "including you who are called to belong to Jesus Christ". | |||

| * Jesus | |||

| ** lives in heaven; | |||

| ** is God's Son; | |||

| ** would soon return.<ref name="Sanders2" /> | |||

| * The Cross | |||

| ** he now believed Jesus' death was a voluntary sacrifice that reconciled sinners with God.{{Bibleref2c|Rom.|5:6-10}} {{Bibleref2c|Phil.|2:8}} | |||

| * The Law | |||

| ** he now believed the law only reveals the extent of people's enslavement to the power of sin—a power that must be broken by Christ.{{Bibleref2c|Rom.|3:20b}} {{Bibleref2c-nb|Rom.|7:7-12}} | |||

| * Gentiles | |||

| ** he had believed Gentiles were outside the covenant that God made with Israel; | |||

| ** he now believed Gentiles and Jews were united as the people of God in Christ Jesus.{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|3:28}} | |||

| * Circumcision | |||

| ** had believed circumcision was the rite through which males became part of Israel, an exclusive community of God's chosen people;{{Bibleref2c|Phil.|3:3-5}} | |||

| ** he now believed that neither circumcision nor uncircumcision means anything, but that the new creation is what counts in the sight of God,{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|6:15}} and that this new creation is a work of Christ in the life of believers, making them part of the church, an inclusive community of Jews and Gentiles reconciled with God through faith.{{Bibleref2c|Rom.|6:4}} | |||

| * Persecution | |||

| ** had believed his violent persecution of the church to be an indication of his zeal for his religion;{{Bibleref2c|Phil.|3:6}} | |||

| ** he now believed Jewish hostility toward the church was sinful opposition that would incur God's wrath;{{Bibleref2c|1Thes|2:14-16||1 Thess. 2:14-16}} <ref name="Powell" />{{rp|p.236}} he believed he was halted by Christ when his fury was at its height;{{Bibleref2c|Acts|9:1-2}} It was "through zeal" that he persecuted the Church,{{Bibleref2c|Philippians|3:6}} and he obtained mercy because he had "acted ignorantly in unbelief".{{Bibleref2c|1tim|1:13||1 Tim. 1:13}}<ref name="disputed" /> | |||

| * The Last Days | |||

| ** had believed God's messiah would put an end to the old age of evil and initiate a new age of righteousness; | |||

| ** he now believed this would happen in stages that had begun with the resurrection of Jesus, but the old age would continue until Jesus returns.{{Bibleref2c|Rom.|16:25}} {{Bibleref2c|1cor|10:11||1 Cor. 10:11}} {{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:4}} <ref name="Powell" />{{rp|p.236}} | |||

| Paul is critical both theologically and empirically of claims of moral or lineal superiority {{Bibleref2c|Rom.|2:16-26}} of Jews while conversely strongly sustaining the notion of a special place for the ].{{Bibleref2c-nb|Rom.|9-11}} | |||

| There are debates as to whether Paul understood himself as commissioned to take the gospel to the Gentiles at the moment of his conversion.<ref>{{Cite book | last1 = Horrell | first1 = David G | title = An Introduction to the Study of Paul | year = 2006 | publisher = T&T Clark | location = New York | isbn = 0-567-04083-6 | page = 30 }}</ref> | |||

| === Early ministry === | === Early ministry === | ||

| ] in ]]] | ] in ]]] | ||

| ], believed to be where Paul escaped from persecution in Damascus]] | ], believed to be where Paul escaped from persecution in Damascus]] | ||

| After his conversion, Paul went to ], where ] states he was healed of his blindness and ] by Ananias of Damascus.{{sfn|Hengel|1997|p=43}} Paul says that it was in Damascus that he barely escaped death.<ref>{{Bibleverse|2 Corinthians|11:32}}</ref> Paul also says that he then went first to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:17}}</ref>{{sfn|Lake|1911|pp=320–23}} Paul's trip to Arabia is not mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, although it has been theorized that he traveled to ] for meditations in the desert.{{sfn|Wright|1996|pp=683–92}}{{sfn|Hengel|2002|pp=47–66}} He describes in ] how three years after his conversion he went to ]. There he met ] and stayed with ] for 15 days.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:13–24}}</ref> Paul located Mount Sinai in Arabia in Galatians 4:24–25.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|4:24–25}}</ref> | |||

| Paul asserted that he received the ] not from man, but directly by "the revelation of Jesus Christ".<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:11–16}}</ref> He claimed almost total independence from the Jerusalem community{{sfn|Harris|2003|p=517}} (possibly in the ]), but agreed with it on the nature and content of the gospel.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:22–24}}</ref> He appeared eager to bring material support to Jerusalem from the various growing ] churches that he started. In his writings, Paul used the ] he endured to avow proximity and union with Jesus and as a validation of his teaching. | |||

| After his conversion, Paul went to ], where ] states he was healed of his blindness and ] by ].<ref>] and Anna Maria Schwemer, trans. John Bowden. '''' Westminster John Knox Press, 1997. ISBN 0-664-25736-4</ref> Paul says that it was in Damascus that he barely escaped death.{{Bibleref2c|2Cor.|11:32||2 Cor. 11:32}} Paul also says that he then went first to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus.{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:17}}<ref>Kirsopp Lake, (London 1911), pp. 320–323.</ref> Paul's trip to Arabia is not mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, and some suppose he actually traveled to Mt. Sinai for meditations in the desert.<ref name=WrightArabia>N.T. Wright, </ref><ref>Martin Hengel, '']'' 12.1 (2002) pp. 47–66.</ref> He describes in Galatians how three years after his conversion he went to ]. There he met James and stayed with ] for 15 days.{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:13-24}} Paul located ] in Arabia in {{Bibleref2|Galatians|4:24-25}}. | |||

| Paul's narrative in Galatians states that 14 years after his conversion he went again to Jerusalem.<ref name="Bibleref2|Gal.|2:1–10">{{Bibleverse|Galatians|2:1–10}}</ref> It is not known what happened during this time, but both Acts and Galatians provide some details.{{sfn|Barnett|2005|p=200}} At the end of this time, ] went to find Paul and brought him to ].{{sfn|Dunn|2009|p=369}}<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|11:26}}</ref> The Christian community at Antioch had been established by Hellenised diaspora Jews living in Jerusalem, who played an important role in reaching a Gentile, Greek audience, notably at Antioch, which had a large Jewish community and significant numbers of Gentile "God-fearers."{{sfn|Dunn|2009|p=297}} From Antioch the mission to the Gentiles started, which would fundamentally change the character of the early Christian movement, eventually turning it into a new, Gentile religion.{{sfn|Dunn|2009}} | |||

| Paul asserted that he received the Gospel not from man, but directly by "the revelation of Jesus Christ".{{Bibleref2c|Gal|1:11-16}} He claimed almost total independence from the Jerusalem community,<ref name="Harris"/>{{rp|pp.316–320}} (possibly in the ]), but agreed with it on the nature and content of the ].{{Bibleref2c|Gal|1:22-24}} He appeared eager to bring material support to Jerusalem from the various budding Gentile churches that he planted. In his writings, Paul used the persecutions he endured, in terms of physical beatings and verbal assaults, to avow proximity and union with Jesus and as a validation of his teaching. | |||

| When a famine occurred in ], around 45–46,{{sfn|Ogg|1962}} Paul and Barnabas journeyed to Jerusalem to deliver financial support from the Antioch community.{{sfn|Barnett|2005|p=83}} According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative center for Christians following the dispersion of the believers after the death of ]. It was in Antioch that the followers of Jesus were first called "Christians".<ref>]</ref> | |||

| Paul's narrative in Galatians states that 14 years after his conversion he went again to Jerusalem.{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|2:1-10}} It is not completely known what happened during these 'unknown years', but both Acts and Galatians provide some partial details.<ref>Barnett, Paul '''' (Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2005) ISBN 0-8028-2781-0 p. 200</ref> At the end of this time, ] went to find Paul and brought him back to ]. {{Bibleref2c|Acts|11:26}} | |||

| When a famine occurred in Judea, around 45–46,<ref>Ogg, George, ''Chronology of the New Testament'' in ] (Nelson, 1963)</ref> Paul and Barnabas journeyed to Jerusalem to deliver financial support from the Antioch community.<ref>Barnett </ref> According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative center for Christians following the dispersion of the believers after the death of Stephen. It was in Antioch that the followers of Jesus were first called "Christians".{{Bibleref2c|Acts|11:26}} | |||

| === First missionary journey === | === First missionary journey === | ||

| ] | |||

| The author of Acts arranges Paul's travels into three separate journeys. The first journey,<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|13–14}}</ref> for which Paul and Barnabas were commissioned by the Antioch community,{{sfn|Dunn|2009|p=370}} and led initially by Barnabas,{{refn|group=note|The only indication as to who is leading is in the order of names. At first, the two are referred to as Barnabas and Paul, in that order. Later in the same chapter, the team is referred to as Paul and his companions.}} took Barnabas and Paul from Antioch to Cyprus then into southern Asia Minor, and finally returning to Antioch. In Cyprus, Paul rebukes and blinds ] the magician<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|13:8–12}}</ref> who was criticizing their teachings. | |||

| They sailed to ] in ]. ] left them and returned to Jerusalem. Paul and Barnabas went on to ]. On ] they went to the synagogue. The leaders invited them to speak. Paul reviewed Israelite history from life in Egypt to King David. He introduced Jesus as a descendant of David brought to Israel by God. He said that his group had come to bring the message of salvation. He recounted the story of Jesus' death and resurrection. He quoted from the ]<ref name="JewEnc:Saul of Tarsus" /> to assert that Jesus was the promised Christos who brought them forgiveness for their sins. Both the Jews and the "]" Gentiles invited them to talk more next Sabbath. At that time almost the whole city gathered. This upset some influential Jews who spoke against them. Paul used the occasion to announce a change in his mission which from then on would be to the Gentiles.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|13:13–48}}</ref> | |||

| The author of the Acts arranges Paul's travels into three separate journeys. The first journey,{{Bibleref2c|Acts|13-14}} led initially by Barnabas,<ref>The only indication as to who is leading is in the order of names. At first, the two are referred to as Barnabas and Paul, in that order. Later in the same chapter the team is referred to as Paul and his companions.</ref> took Paul from Antioch to Cyprus then into southern Asia Minor (Anatolia), and finally returning to Antioch. In Cyprus, Paul rebukes and blinds ] the magician{{Bibleref2c|Acts|13:8-12}} who was criticizing their teachings. From this point on, Paul is described as the leader of the group.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.biblestudy.org/maps/pauls-first-journey-map.html |title=Map of first missionary journey |publisher=Biblestudy.org |accessdate=2010-11-19}}</ref> | |||

| Antioch served as a major Christian home base for Paul's early missionary activities,{{sfn|Harris|2003}} and he remained there for "a long time with the disciples"<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|14:28|NKJV}}</ref> at the conclusion of his first journey. The exact duration of Paul's stay in Antioch is unknown, with estimates ranging from nine months to as long as eight years.{{sfn|Spence-Jones|2015|p=16}} | |||

| They sail to ] in ]. John Mark leaves them and returns to Jerusalem. Paul and Barnabas go on to Pisidian Antioch. On ] they go to the synagogue. The leaders invite them to speak. Paul reviews Israelite history from life in Egypt to King David. He introduces Jesus as a descendant of David brought to Israel by God. He said that his team came to town to bring the message of salvation. He recounts the story of Jesus' death and resurrection. He quotes from the ]<ref name="paul">"His quotations from Scripture, which are all taken, directly or from memory, from the Greek version, betray no familiarity with the original Hebrew text (..) Nor is there any indication in Paul's writings or arguments that he had received the rabbinical training ascribed to him by Christian writers (..)"{{cite web|title=Paul, the Apostle of the Heathen|url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11952-paul-of-tarsus|publisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com|accessdate=2012-02-10}}</ref> to assert that Jesus was the promised ]os who brought them forgiveness for their sins. Both the Jews and the ']' Gentiles invited them to talk more next Sabbath. At that time almost the whole city gathered. This upset some influential Jews who spoke against them. Paul used the occasion to announce a change in his mission which from then on would be to the Gentiles.{{Bibleref2c|Acts|13:13-48}} | |||

| In ]'s ''An Introduction to the New Testament'', published in 1997, a chronology of events in Paul's life is presented, illustrated from later 20th-century writings of ]s.{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=445}} The first missionary journey of Paul is assigned a "traditional" (and majority) dating of 46–49 AD, compared to a "revisionist" (and minority) dating of after 37 AD.{{sfn|Brown|1997|pp=428–29}} | |||

| ===Interval at Antioch=== | |||

| Antioch served as a major Christian center for Paul's evangelizing.<ref name="Harris"/> Paul remained there for 'some time' <ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|14:28|NKJV}}</ref> or 'a long time' in other translations <ref>e.g. ], ]</ref> at the conclusion of his first journey. 'Bishop Pearson reckons it a little more than a year'. Lewin estimated it as "about a year;" Renan suggested "several months". The writer of the ] argues that 'no accurate statement can be gathered from St. Luke's indefinite expression".<ref>All quotes from Pulpit Commentary on Acts 14, http://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/acts/14.htm accessed 9 September 2015</ref> | |||

| === Council of Jerusalem === | === Council of Jerusalem === | ||

| {{Main|Council of Jerusalem}} | {{Main|Council of Jerusalem}} | ||

| {{See also|Circumcision controversy in early Christianity}} | {{See also|Circumcision controversy in early Christianity}} | ||

| A vital meeting between Paul and the Jerusalem church took place in the year 49 AD by traditional (and majority) dating, compared to a revisionist (and minority) dating of 47/51 AD.{{sfn|Brown|1997|pp=428–29, 445}} The meeting is described in Acts 15:2<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|15:2|NIV}}</ref> and usually seen as the same event mentioned by Paul in {{Bibleverse|Galatians|2:1-10|NRSV}}{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|loc=St Paul}} The key question raised was whether ] converts needed to be circumcised.{{sfn|Bechtel|1910}}<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|15:2|NIV}},{{Bibleverse|Galatians|2:1|NIV}}</ref> At this meeting, Paul states in his letter to the Galatians, ], ], and ] accepted Paul's mission to the Gentiles. | |||

| The Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, and also in Paul's letters.{{sfn|White|2007|pp=148–49}} For example, the Jerusalem visit for famine relief<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|11:27–30}}</ref> apparently corresponds to the "first visit" (to Peter and James only).<ref name="Bibleref2|Gal.|1:18–20">{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:18–20}}</ref>{{sfn|White|2007|pp=148–49}} ] suggested that the "fourteen years" could be from Paul's conversion rather than from his first visit to Jerusalem.{{sfn|Bruce|2000|p=151}} | |||

| Most scholars agree that a vital meeting between Paul and the Jerusalem church took place some time in the years 48 to 50, described in {{Bibleref2|Acts|15:2|NIV}} and usually seen as the same event mentioned by Paul in {{Bibleref2|Galatians|2:1|NIV}}.<ref name="ODCC self" /> The key question raised was whether ] converts needed to be circumcised.<ref>{{Bibleref2|Acts|15:2|NIV}}ff; {{Bibleref2|Galatians|2:1|NIV}}ff</ref> At this meeting, Paul states in his letter to the Galatians that Peter, James, and John accepted Paul's mission to the Gentiles. | |||

| Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, in Paul's letters, and some appear in both.<ref name="white">{{cite book | |||

| | pages=148–149 | |||

| | url=https://books.google.com/?id=w4ehxXoIxCUC&pg=PA149&q=paul+%22visits+to+jerusalem%22+acts+letters | |||

| | first=L. Michael | |||

| | last=White | |||

| | title=From Jesus to Christianity | |||

| | publisher=HarperCollins | |||

| | isbn=0-06-052655-6 | |||

| | year=2004}}</ref> For example, the Jerusalem visit for ] relief{{Bibleref2c|Acts|11:27-30}} apparently corresponds to the "first visit" (to Cephas and James only).{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:18-20}}<ref name="white" /> F. F. Bruce suggested that the "fourteen years" could be from Paul's conversion rather than from his first visit to Jerusalem.<ref>''Paul: Apostle of the Free Spirit,'' ], Paternoster 1980, p.151</ref> | |||

| === Incident at Antioch === | === Incident at Antioch === | ||

| {{Main|Incident at Antioch}} | {{Main|Incident at Antioch}} | ||

| Despite the agreement achieved at the Council of Jerusalem, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter in a dispute sometimes called the "]", over Peter's reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch because they did not strictly adhere to Jewish customs.{{sfn|Bechtel|1910}} | |||

| Writing later of the incident, Paul recounts, "I opposed to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong", and says he told Peter, "You are a Jew, yet you ]. How is it, then, that you ]?"<ref name="Bibleref2|Gal.|2:11–14">{{Bibleverse|Galatians|2:11–14}}</ref> Paul also mentions that even Barnabas, his traveling companion and fellow apostle until that time, sided with Peter.{{sfn|Bechtel|1910}} | |||

| Despite the agreement achieved at the Council of Jerusalem, as understood by Paul, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter in a dispute sometimes called the "Incident at Antioch", over Peter's reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch because they did not strictly adhere to Jewish customs.<ref name=cathen-incident> see section titled: "The Incident At Antioch"</ref> | |||

| The outcome of the incident remains uncertain. The '']'' suggests that Paul won the argument, because "Paul's account of the incident leaves no doubt that Peter saw the justice of the rebuke".{{sfn|Bechtel|1910}} However, Paul himself never mentions a victory, and ]'s ''From Jesus to Christianity'' draws the opposite conclusion: "The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as ''persona non grata'', never again to return".{{sfn|White|2007|p=170}} | |||

| Writing later of the incident, Paul recounts, "I opposed to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong", and says he told Peter, "You are a Jew, yet you ]. How is it, then, that you ]?"{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|2:11-14}} Paul also mentions that even Barnabas, his traveling companion and fellow apostle until that time, sided with Peter.<ref>: "On their arrival Peter, who up to this had eaten with the Gentiles, 'withdrew and separated himself, fearing them who were of the circumcision,' and by his example drew with him not only the other Jews, but even Barnabas, Paul's fellow-labourer".</ref> | |||

| The primary source account of the incident at Antioch is Paul's ].<ref name="Bibleref2|Gal.|2:11–14"/> | |||

| The final outcome of the incident remains uncertain. The '']''<ref name=cathen-incident/> suggests that Paul won the argument, because "Paul's account of the incident leaves no doubt that Peter saw the justice of the rebuke". However Paul himself never mentions a victory and ]'s ''From Jesus to Christianity'' draws the opposite conclusion: "The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as ], never again to return".<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | page=170 | |||

| | url=https://books.google.com/?id=w4ehxXoIxCUC&pg=PA170&q=paul+%22visits+to+jerusalem%22+acts+letters | |||

| | first=L. Michael | |||

| | last=White | |||

| | title=From Jesus to Christianity | |||

| | publisher=HarperSanFrancisco | |||

| | year=2004 | |||

| | isbn=0-06-052655-6}}</ref> | |||

| The ] account of the Incident at Antioch is Paul's letter to the Galatians. | |||

| === Second missionary journey === | === Second missionary journey === | ||

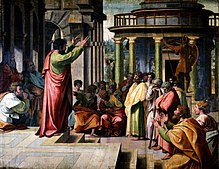

| ] delivering the '']'' in |

] delivering the '']'' in which he addressed early issues in ], depicted in a 1515 portrait by ]{{sfn|McGrath|2006}}{{sfn|Mills|2003|pp=1109–10}}]] | ||

| Paul left for his second missionary journey from Jerusalem, in late Autumn 49 AD,{{sfn|Köstenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|p=400}} after the meeting of the ] where the circumcision question was debated. On their trip around the Mediterranean Sea, Paul and his companion Barnabas stopped in Antioch where they had a sharp argument about taking ] with them on their trips. The Acts of the Apostles said that John Mark had left them in a previous trip and gone home. Unable to resolve the dispute, Paul and Barnabas decided to separate; Barnabas took John Mark with him, while ] joined Paul. | |||

| Paul left for his second missionary journey from Jerusalem, in late Autumn 49,<ref>Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum and Charles Quarles (2009). Nashville, Tennessee, B&H Publishing Group. p. 400</ref> after the meeting of the ] where the circumcision question was debated. On their trip around the Mediterranean sea, Paul and his companion Barnabas stopped in Antioch where they had a sharp argument about taking ] with them on their trips. The book of Acts said that John Mark had left them in a previous trip and gone home. Unable to resolve the dispute, Paul and Barnabas decided to separate; Barnabas took John Mark with him, while ] joined Paul. | |||

| Paul and Silas initially visited ] (Paul's birthplace), ] and ]. In Lystra, they met ], a disciple who was spoken well of, and decided to take him with them. The Church kept growing, adding believers, and strengthening in faith daily.{{ |

Paul and Silas initially visited ] (Paul's birthplace), ] and ]. In Lystra, they met ], a disciple who was spoken well of, and decided to take him with them. Paul and his companions, Silas and Timothy, had plans to journey to the southwest portion of Asia Minor to preach the gospel but during the night, Paul had a vision of a man of Macedonia standing and begging him to go to Macedonia to help them. After seeing the vision, Paul and his companions left for Macedonia to preach the gospel to them.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|16:6–10}}</ref> The Church kept growing, adding believers, and strengthening in faith daily.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|16:5|KJV}}</ref> | ||

| In ], Paul cast a spirit of divination out of a servant girl, whose masters were then unhappy about the loss of income her soothsaying provided |

In ], Paul cast a spirit of divination out of a servant girl, whose masters were then unhappy about the loss of income her soothsaying provided.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|16:16–24}}</ref> They seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace before the authorities and Paul and Silas were put in jail. After a miraculous earthquake, the gates of the prison fell apart and Paul and Silas could have escaped but remained; this event led to the conversion of the jailor.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|16:25–40}}</ref> They continued traveling, going by ] and then to Athens, where Paul preached to the Jews and God-fearing Greeks in the synagogue and to the Greek intellectuals in the ]. Paul continued from Athens to ]. | ||

| ===Interval in Corinth=== | ===Interval in Corinth=== | ||

| Around 50–52, Paul spent 18 months in Corinth. The reference in Acts to Proconsul ] helps ascertain this date (cf. ]). |

Around 50–52 AD, Paul spent 18 months in ]. The reference in Acts to Proconsul ] helps ascertain this date (cf. ]).{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|loc=St Paul}} In Corinth, Paul met ],<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|18:2|NKJV}}</ref> who became faithful believers and helped Paul through his other missionary journeys. The couple followed Paul and his companions to ] and stayed there to start one of the strongest and most faithful churches at that time.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|18:18–21|NKJV}}</ref> | ||

| In 52, departing from Corinth, Paul stopped at the nearby village of ] to have his hair cut off, because of a vow he had earlier taken.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|18:18|NKJV}}</ref> It is possible this was to be a final haircut before fulfilling his vow to become a ] for a defined period of time.{{sfn|Driscoll|1911}} With Priscilla and Aquila, the missionaries then sailed to Ephesus<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|18:19–21|NKJV}}</ref> and then Paul alone went on to ] to greet the Church there. He then traveled north to Antioch, where he stayed for some time ({{langx|grc|ποιήσας χρόνον τινὰ }}.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|18:22-23|NKJV}}</ref> Some New Testament texts{{refn|group=note|This clause is not found in some major sources: ], ], ] or Codex Laudianus}} suggest that he also visited Jerusalem during this period for one of the Jewish feasts, possibly ].<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|18:21|NKJV}}</ref> Textual critic ] and others consider the reference to a Jerusalem visit to be genuine<ref name="PulCom" /> and it accords with Acts 21:29,<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|21:29|NKJV}}</ref> according to which Paul and ] had previously been seen in Jerusalem. | |||

| === Third missionary journey === | === Third missionary journey === | ||

| ]'', a 1649 portrait by ]{{sfn|Crease|2019|pp=309–10}}]] | |||

| According to Acts, Paul began his third missionary journey by traveling all around the region of ] and ] to strengthen, teach and rebuke the believers. Paul then traveled to ], an important ], and stayed there for almost three years, probably working there as a tentmaker,<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|20:34|NKJV}}</ref> as he had done when he stayed in ]. He is said to have performed numerous miracles, healing people and casting out demons, and he apparently organized missionary activity in other regions.{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|loc=St Paul}} Paul left Ephesus after an attack from a local silversmith resulted in a pro-] riot involving most of the city.{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|loc=St Paul}} During his stay in Ephesus, Paul wrote four letters to the church in Corinth.{{sfn|McRay|2007|p=185}} The letter to the church in ] is generally thought to have been written from Ephesus, though a minority view considers it may have been penned while he was imprisoned in Rome.<ref>Michael Flexsenhar 111, ] Volume 42, Issue 1 2019 : 18-45.</ref> | |||

| Paul went through ] into ]<ref name="bibleref2|Acts|20:1–2|NKJV">{{bibleverse|Acts|20:1–2|NKJV}}</ref> and stayed in Greece, probably Corinth, for three months<ref name="bibleref2|Acts|20:1–2|NKJV"/> during 56–57 AD.{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|loc=St Paul}} Commentators generally agree that Paul dictated his ] during this period.{{sfn|Sanday|n.d.|p=202}} He then made ready to continue on to ], but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia, putatively because certain Jews had made a plot against him. In Romans 15:19,<ref>{{bibleverse|Romans|15:19}}</ref> Paul wrote that he visited ], but he may have meant what would now be called ],{{sfn|Burton|2000|p=26}} which was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.{{sfn|Petit|1909}} On their way back to Jerusalem, Paul and his companions visited other cities such as ], ], ], ], and ]. Paul finished his trip with a stop in ], where he and his companions stayed with ] before finally arriving in Jerusalem.<ref>{{bibleverse|Acts|21:8–10}}, {{bibleverse|Acts|21:15}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ], Paul began his third missionary journey by travelling all around the region of Galatia and Phrygia to strengthen, teach and rebuke the believers. Paul then traveled to Ephesus, an important ], and stayed there for almost three years, probably working there as a tentmaker,<ref>{{bibleverse||Acts|20:34|NKJV}}</ref> as he had done when he stayed in Corinth. He is claimed to have performed numerous miracles, healing people and casting out demons, and he apparently organized missionary activity in other regions.<ref>"Paul, St". Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005</ref> Paul left Ephesus after an attack from a local silversmith resulted in a pro-] riot involving most of the city.<ref name="ODCC self" /> During his stay in Ephesus, Paul wrote four letters to the church in Corinth.<ref name=McRay185>{{cite book|last=McRay|first=John|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GvgexcfnWC0C&pg=PT185#v=snippet&q=%22four%20letters%20to%20the%20church%20in%20Corinth%22&f=false |title=Paul His Life and Teaching|year=2007|publisher=Baker Academic|location=Grand Rapids, MI |isbn=978-1441205742 |page=185}}</ref> | |||

| ===Conjectured journey from Rome to Spain=== | |||

| Paul went through ] into ] ({{bibleref2|Acts|20:1-2|NKJV}}) and stayed in Greece, probably Corinth, for three months ({{bibleref2|Acts|20:1-2|NKJV}}) during 56-57 AD.<ref name="ODCC self" /> He then made ready to continue on to Syria, but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia because of Jews who had made a plot against him. | |||

| Among the writings of the early Christians, ] said that Paul was "Herald (of the Gospel of Christ) in the West", and that "he had gone to the extremity of the west".<ref> Early Christian Writings 1 Clem 5:5: "By reason of jealousy and strife Paul by his example pointed out the prize of patient endurance. After that he had been seven times in bonds, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, had preached in the East and in the West, he won the noble renown which was the reward of his faith, having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the farthest bounds of the West; and when he had borne his testimony before the rulers, so he departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance".</ref> | |||

| Where ]'s translation has "had preached" below (in the "Church tradition" section), the Hoole translation has "having become a herald".<ref>See also the endnote (3) by ] on the last page of ] regarding Paul's preaching in Britain.</ref> ] indicated that Paul preached in Spain: "For after he had been in Rome, he returned to Spain, but whether he came thence again into these parts, we know not".<ref>, verse 4:20</ref> ] said that Paul, "fully preached the Gospel, and instructed even imperial Rome, and carried the earnestness of his preaching as far as Spain, undergoing conflicts innumerable, and performing Signs and wonders".<ref>] (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II Volume VII, Lecture 17, para. 26)</ref> The ] mentions "the departure of Paul from the city (39) when he journeyed to Spain".<ref> lines 38–39 Bible Research</ref> | |||

| In {{bibleref2|Romans|15:19}} Paul wrote that he visited ], but he may have meant what would now be called ],<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=b52QYgZg6W8C&pg=PR26#v=onepage&q=%22illyris%20graeca%22&f=false |title=A critical and exegetical commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians |publisher=|accessdate=2010-11-19|isbn=978-0-567-05029-8|year=1977|author1=Burton|first1=Ernest De Witt}}</ref> which lay in the northern part of modern Albania, but was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.<ref>. Newadvent.org (1909–05–01). Retrieved 2010–11–19.</ref> | |||

| Paul and his companions visited other cities on their way back to Jerusalem such as Philippi, Troas, Miletus, ], and ]. Paul finished his trip with a stop in Caesarea, where he and his companions stayed with ] before finally arriving at Jerusalem.<ref> Biblestudy.org</ref> {{bibleref2c|Acts|21:8-10}} {{bibleref2c-nb|Acts|21:15}} | |||

| === Journey to Rome and beyond === | |||

| After Paul's arrival in Jerusalem at the end of his third missionary journey, he became involved in a serious conflict with some "Asian Jews" (most likely from ]). The conflict eventually led to Paul's arrest and imprisonment in ] for two years. Finally, Paul and his companions sailed for Rome where Paul was to stand trial for his alleged crimes. ''Acts'' states that Paul preached in Rome for two years from his rented home while awaiting trial. It does not state what happened after this time, but some sources state that Paul was freed by ] and continued to preach in Rome, even though that seems unlikely{{according to whom|date=September 2015}} based on Nero's historical cruelty to ]s. See ''His final days spent in Rome'' section below. | |||

| Among the writings of the early Christians, ] said that Paul was "Herald (of the Gospel of Christ) in the West", and that "he had gone to the extremity of the west".<ref name="scarlet"></ref><ref><br/>1 Clem 5:5 "By reason of jealousy and strife Paul by his example pointed out the prize of patient endurance. After that he had been seven times in bonds, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, <u>had preached</u> in the East and in the West, he won the noble renown which was the reward of his faith, having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the <u>farthest bounds of the West</u>; and when he had borne his testimony before the rulers, so he departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance".<br/>Where ] has "had preached" above, the has "having become a herald".<br/>See also the endnote(#3) by ] on the last page of ] regarding Paul's preaching in Britain.</ref> ] indicated that Paul preached in Spain: "For after he had been in Rome, he returned to Spain, but whether he came thence again into these parts, we know not".<ref>] (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series I Volume XIII)</ref> ] said that Paul, "fully preached the Gospel, and instructed even imperial Rome, and carried the earnestness of his preaching as far as Spain, undergoing conflicts innumerable, and performing Signs and wonders".<ref>] (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II Volume VII, Lecture 17, para.26)</ref> The ] mentions "the departure of Paul from the city (39) when he journeyed to Spain".<ref> lines 38–39</ref> | |||

| === Visits to Jerusalem in Acts and the epistles === | === Visits to Jerusalem in Acts and the epistles === | ||

| The following table is adapted from the book ''From Jesus to Christianity'' by Biblical scholar ],{{sfn|White|2007|pp=148–49}} matching Paul's travels as documented in the Acts and the travels in his ] but not agreed upon fully by all Biblical scholars. | |||

| {{Christianity|state=collapsed}} | |||

| This table is adapted from White, ''From Jesus to Christianity.''<ref name="white" /> Note that the matching of Paul's travels in the Acts and the travels in his Epistles is done for the reader's convenience and is not approved of by all scholars. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="margin:auto;" cellpadding="5" | {| class="wikitable" style="margin:auto;" cellpadding="5" | ||

| Line 228: | Line 183: | ||

| |- -valign="top" | |- -valign="top" | ||

| | style="text-align:left;"| | | style="text-align:left;"| | ||

| * First visit to Jerusalem<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|9:26–27}}</ref> | |||

| * First visit to Jerusalem{{Bibleref2c|Acts|9:26-27}} | |||

| ** "after many days" of Damascus conversion | ** "after many days" of Damascus conversion | ||

| ** preaches openly in Jerusalem with Barnabas | ** preaches openly in Jerusalem with Barnabas | ||

| ** meets apostles | ** meets apostles | ||

| | style="text-align:left; vertical-align:top;"| | | style="text-align:left; vertical-align:top;"| | ||

| * First visit to Jerusalem<ref name="Bibleref2|Gal.|1:18–20"/> | |||

| ** three years after Damascus conversion<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|1:17–18}}</ref> | |||

| * First visit to Jerusalem{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:18-20}} | |||

| ** sees only Cephas (Simon Peter) and James | |||

| ** three years after Damascus conversion{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|1:17-18}} | |||

| ** sees only Cephas (Peter) and James | |||

| |- -valign="top" | |- -valign="top" | ||

| | style="text-align:left;"| | | style="text-align:left;"| | ||

| * Second visit to Jerusalem<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|11:29–30}}, {{Bibleverse|Acts|12:25}}</ref> | |||

| * Second visit to Jerusalem{{Bibleref2c|Acts|11:29-30}} {{Bibleref2c-nb|Acts|12:25||, 12:25}} | |||

| ** for famine relief | ** for famine relief | ||

| | style="text-align:left; vertical-align:top;"| | | style="text-align:left; vertical-align:top;"| | ||

| * There is debate over whether Paul's visit in Galatians 2 refers to the visit for famine relief<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|11:30, 12:25}}</ref> or the Jerusalem Council.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|15}}</ref> If it refers to the former, then this was the trip made "after an interval of fourteen years".<ref>{{Bibleverse|Galatians|2:1}}</ref> | |||

| * There is debate over whether Paul's visit in Galatians 2 refers to the visit for famine relief{{Bibleref2c|Acts|11:30,12:25||Acts 11:30, 12:25}} or the Jerusalem Council.{{Bibleref2c|Acts|15}} If it refers to the former, then this was the trip made "after an interval of fourteen years".{{Bibleref2c|Gal.|2:1}} | |||

| |- -valign="top" | |- -valign="top" | ||

| | style="text-align:left;"| | | style="text-align:left;"| | ||

| * Third visit to Jerusalem<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|15:1–19}}</ref> | |||

| * Third visit to Jerusalem{{Bibleref2c|Acts|15:1-19}} | |||

| ** with Barnabas | ** with Barnabas | ||

| ** "Council of Jerusalem" | ** "Council of Jerusalem" | ||

| ** followed by confrontation with Barnabas in Antioch{{ |

** followed by confrontation with Barnabas in Antioch<ref>{{Bibleverse|Acts|15:36–40}}</ref> | ||

| | style="text-align:left; vertical-align:top;"| | | style="text-align:left; vertical-align:top;"| | ||

| * Another{{refn|group=note|Paul does not exactly say that this was his second visit. In Galatians, he lists three important meetings with Peter, and this was the second on his list. The third meeting took place in Antioch. He does not explicitly state that he did not visit Jerusalem in between this and his first visit.}} visit to Jerusalem<ref name="Bibleref2|Gal.|2:1–10"/> | |||